Every September, we returned to the Educational Institution after two month’s summer vacation, during which we worked on our kibbutzim.

From one year to the next, everything became more. In the tenth grade, it was as if we’d moved all at once from thinking to acting, from standing to moving. We no longer exaggerated when we talked about what we did. What we did exaggerated itself. We collided with the world. The world was present, and so were we and what we did.

Love remained intangible, but its results were felt everywhere: Couples walked hand in hand all the time; some girls stayed on their kibbutzim with volunteers, or with boys from their groups, slipping back to the Educational Institution in the morning. There were couples who slept together in the Institution and went back to their beds before the metaplot went from room to room waking us up. Some couples walked along the peripheral road that encircled the Institution up to the reservoir, or had sex in the air raid shelters on thin mattresses, or without mattresses at all, or on a blanket outside; some had sex on the beds in their rooms, and sometimes, the others who lived in those rooms were there, lying on the other beds, and sometimes they weren’t.

On the afternoons when we didn’t work, we wandered or stretched out on the lawn near our classroom in Seagull, or we sat in the basketball court stands, looking beyond the boys playing there, or stared at the ground as we drew imaginary circles on earth and concrete with branches.

“I’m late this month,” one of the girls would sometimes say in terror during those moments, as if the words were being pushed out of her mouth against her will. We caught our breath, looked at her for a moment, checked ourselves, not knowing whether it was happening in our bodies or in our friend’s, no matter if we’d had sex already or not. As if the power of fear alone could impregnate us with something we’d never known before. What was she saying now, something about herself or about us? How should we reply?

Abortions were arranged by the kibbutzim, not the Institution. On Yehiam, my mother was the nurse, and the abortions were done in Nahariya, with the kibbutz nurse. Anyone who had to go through it, went through it. Once or twice or three times. They said it wasn’t a matter of luck, that something could be done to prevent it from happening. But it was a matter of luck too—once or twice or three times.

In the morning, during breaks, we talked with the girls about what love was, and at night, sometimes with the boys. We thought constantly about what love was. We opened and closed our eyes when we talked about it, we looked at the sky or the ground to keep from looking into the eyes of the people who were speaking. We thought they couldn’t see anything on us. We hoped they couldn’t see anything on us. There was nowhere to hide. We were always in the light—the sunlight in the morning and the lamps at night, in the rooms that four of us shared, one in each corner, where someone was always reading or doing something else with the light on.

Those who didn’t want to see or be seen covered their eyes with their hands.

Idit and I wrote to each other constantly. During classes and afterwards. And we were always together anyway. When everything was exaggerated and had become more—we also moved into the same room.

We moved into the room that adjoined our classroom. An open concrete area separated those two rooms from the rest of the long building that contained all the other rooms, the two communal shower rooms (one for boys, one for girls) and the two communal bathrooms we all used. “Our” room was tiny. Until we invaded it, it had been called “the metapelet’s room,” and it contained a supply of toilet paper as well as tea and sugar for the coffee corner that was right next to it. Once a year, they held a round of homeroom teachers’ talks in it. But most of the year, it was empty. The emptiness piqued our interest. We made it habitable and simply moved into it. They couldn’t find a clause that would support an objection, and we stayed there.

Later, we opened a teahouse in an empty air raid shelter. We painted it blue, and Idit drew an enormous mural on one of the walls. Using a magic lantern, she projected the original on the wall and for days, she worked on a painting on the blue wall. In the Regional Council building, we found a huge record collection kept there by Arieh, the music teacher from Beit Haemek. We moved the collection to our teahouse. We told each other that if Arieh knew where his classical music records had disappeared to, he might even be happy about it. We made menus listing a variety of teas and announced the opening of our teahouse. People read there, drank tea, listened to Beethoven symphonies from Arieh’s collection, and sometimes held meetings of the newsletter or cultural committees there. The teahouse became one of the places to wander to. All the places that weren’t locked were also accessible in the evenings—the reading room, the painting room, the music room, the shelters where instrumental groups and singers rehearsed. We wandered from place to place, searching for quiet, searching for noise. Everyone asked, “Where is everyone?”

Idit and I saw signs in everything, as if our eyes kept opening wider and wider until the shadow of hills looked like hills or like valleys to us. We preferred living the signs to living the world. We tried to avoid the world, to keep it at bay behind the door, to prevent any contact between us and it.

Idit studied painting, music and dancing. I read, fasted, abstained and swore oaths. First I stopped eating meat for a week. Then I tried not to eat at all for a few days. Then I stopped talking for a week. When my teachers asked me about that, I handed them a page of explanation I’d written.

We felt that if we isolated things we might understand or know. We wrote down the dreams we had at night, believed that they spoke the truth. We searched for truth as if it were an object we couldn’t see in the dark.

When Margalit came to wake us in the morning, I fainted at the end of one of my fasts. She was frightened. She stood at the door to our room and explained to us the world we were trying to avoid. She said that there were people who didn’t stop observing things from the outside even after their adolescence, people who never really entered life, and that kept them adolescents ever after they’d become adults. Everyone knows where adolescence begins, she said, but no one knows where it ends.

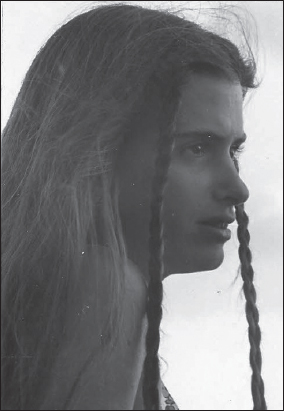

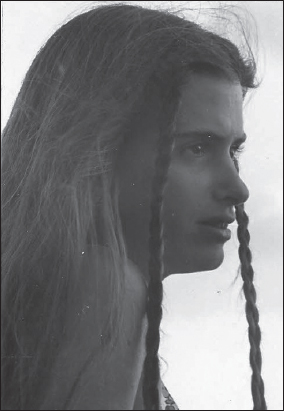

Yael at the Educational Institution.

Two meters separated Idit and me in our room, and three meters separated my desk from hers in class—she sat diagonally in front of me. And the shorter the distance between us, the longer our letters grew.

We were all children of the system, its students, and we usually became youth movement leaders (the Hashomer Hatzair movement, of course), in the tenth grade. When we were in the ninth grade, the Grove group, which was a grade ahead of us, didn’t have enough group leaders, so I became a youth group leader together with Rami, who was already in the tenth grade.

Apart from organizing the activities, which took place once a week in the Nahariya Hashomer Hatzair chapter, Rami and I also went to camps and on trips together. Walking the road to Nahariya with Rami was the continuation of a much longer path, as if we’d walked it together even before we were born, in other landscapes.

Our mothers had known each other back in Budapest, and were already friends there. Later they were in the same Hashomer Hatzair core group, The First of May. Then after the war, each came separately to the same Shuffiya hills, my mother to Yehiam and his to Gaaton.

Rami’s parents, along with Rami and his three sisters, came to visit us on Yehiam, and we visited them on Gaaton; we lived two kilometers apart. Rami’s older sisters were the same age as my older brothers, and had been in the same groups at the Educational Institution since they were twelve. His sisters played the violin and viola, Rami played the cello and his father and youngest sister also played the violin, so that in almost any situation, they could play a quartet.

When we became youth group leaders together, we discovered that we had both signed out the same library books. The Institution library was open five days a week. It contained thousands of books: textbooks, literary fiction and reference books. All the newest books of fiction fell apart when Rami or I read them the first time. We could also borrow books from the kibbutz libraries, which were even larger. By looking at the lenders card in a book, we could tell who had read it before us.

Rami, Idit and I also loved going to shows, plays and concerts in the Evron hall.

We didn’t have to move from where we were. In those days, we were the center of the world, and everyone came to us. Performers toured all the kibbutzim; the culture committees had huge budgets. Kibbutz Evron had a modern hall with excellent acoustics. We saw major singers there, as well as fringe performers who would become major several years later. We could get in to see anything. We heard all the concerts and saw all the plays and dance performances.

When Rami and I completed our year as youth group leaders, I continued to speak to him in my mind. At first, I thought it was out of habit, that we used to talk like that while walking to our group activities in Nahariya, on the trips and on our way to the youth camps. Then I thought that it might be because of our families’ years of friendship.

But it was something else, something that persisted. As if the previous order of my life were betraying me, refusing to return to what it had been.

Idit and I wrote each other and talked about Rami too, asking why it was that the girls never loved the boys who loved them and vice versa. Rami asked Idit to be his girlfriend when we were in the eighth grade, and Tali, of the Grove group, would occasionally come to a Seagull girl with a proposal from a Grove boy to be his girlfriend. Idit met with Rami then and told him that she wasn’t interested. And she didn’t become interested later on either. As far as she was concerned, it belonged to the past.

But I grew entrapped in my thoughts of him, as if they had become a giant labyrinth, a hidden city, an entire world. I began to see signs in everything: After all, we borrowed the same library books and always went to the same performances; after all, Romeo and Juliet could have been Ram and Yael, like in Itzhak Salkinson’s old translation of the play, which we had both taken out of the library; after all, we could have been neighbors living two kilometers apart not only in Gaaton and Yehiam, but in Buda and Pest, and instead of swimming in the Gaaton River, we could have swum in the freezing water of the Danube like my mother had, like perhaps his mother had.

At night, I dreamt about Rami. Simple dreams, with no plot complications. As if a plot would only conceal him. The melody of the dream was sweet, like the absence of worry. And while the plot was so clear at night, I didn’t understand it in the morning.

When none of that passed, I wrote him an eleven-page letter. I wrote that I didn’t know whether I loved him or just thought about him, whether I spoke to him or just to an imaginary figure I could direct my inner speech at. (Sometimes I thought of him as a huge cat because he had soft, almost white hair and his eyes were as green as a cat’s. He always walked quietly, stepping high, as if he were drawn by the air, not the ground, and because of the total silence he walked within, he would always appear in unexpected places.)

Rami received the letter, and in the Institution’s dining hall, when we were stacking dishes in the large stainless steel sinks, he came over to me. We arranged to meet at eight that night at the regular place, the bus stop, where the circular paths around the Institution began. We walked to the Regional Council building. Flowers grew there and the grass was green and soft. Rami said that I was going around in circles, that everything was simple. “The complication is only in your mind,” he said. “Love is as simple as knowledge,” he said.

At the end of my first notebook of dreams, I wrote about the image of Rami that appeared constantly in my dreams:

Rami—my relationship to him is not very clearly defined. We were youth group leaders together, and at some point, I was sure that I loved him. Maybe sometimes now too. Even after writing to him and seeing him, I still feel the same way, that I don’t know. Zohar appears in my dreams a lot, and always with Rami. I think that Zohar in my dreams is a symbol of what I’d like to continue being, because on one hand, Zohar is like me, from Seagull and from Yehiam, but on the other, the relationship between Rami and Zohar is not “suspicious” because they’re both boys, and also because Zohar has a good reason to be with Rami—they both play in the same music group. Back when we saw each other a lot, because we were group leaders together, we didn’t need a reason or an excuse, and we didn’t need to define our relationship exactly, love or friendship. It just was.

All that time, Rami loved Idit. He asked her to be his girlfriend twice. The first time, when we were in the eighth grade, and the second time, he went to see her in the piano room when she was playing and tried to persuade her. That was several months after the long letter I wrote to him and after he and I walked to the Regional Council building, and at the same time, Idit and I were writing to each other about how the girls never loved the boys who loved them and vice versa.

Back then, so many things happened in a few months. The ones who loved, no longer loved, and the ones who didn’t love—loved. But between Rami and Idit, nothing changed during those two years.

I was sick, and back on Yehiam because when we were unwell or pregnant, when something went wrong, we left the Institution and stayed on the kibbutz until we were healthy again. Even when we were on our kibbutzim, Idit and I wrote to each other every day. (There were no phones in our parents’ houses, and of course, not in the Institution either. On Yehiam, there was one phone available to the members. They would turn off the meter after they used it, and write in pencil the number of calls they made. That was only so the kibbutz could keep track—no one was charged.) We sent the letters we wrote with our teachers, who traveled to the Institution and back every day.

Idit wrote to me:

This is how I felt this morning/or: The Night of the 15th …/or: The Fall

You’ll understand in a minute what all those titles hint at, and when you get well, I’ll tell you everything and I hope it won’t make you sick again. I keep thinking that you know what happened yesterday and I really don’t have to tell you, but…

Silence…

Yesterday, Rami asked me to be his girlfriend. In a totally egotistical way. He said: “I know that things can’t get any worse for me than they are now (time did not make it better). I’ve been stuck in the same place for two years,” and he thinks and asks me to be his girlfriend, no matter where it leads, just as long as it leads somewhere.

He tried to get back on his feet, but fell again—hopeless. He sees himself as a different person after those two years, even when it comes to me. He wants to get to know me and know how things will end up… He said that he knows I’m the one who has to make the effort, but he’s asking me to make it because he thinks he has no other choice now. It never occurred to him that the answer would be “no,” and he also said that he couldn’t consider the possibility of a no, but he knew about Micah the whole time.

Okay, that’s more or less what I remember of what he said, but I’ll also tell you what I said.

I hope that this isn’t making you mad… He’s smart and all that, but he’s NOT FOR ME.

I explained to him, and in a nice way (as nice as such a thing can be) that I don’t feel anything for him, and that if I said yes, it would only be OUT OF PITY, and not because I feel anything for him. It would go against my feelings, and not worth the effort because what does being boyfriend and girlfriend mean? It means doing things WITH SOMEONE, not TO SOMEONE (I’m really starting to feel like it’s pissing me off already).

He kept saying, think it over, think it over…

What is there to think about here, except the way to say no? I explained my position clearly. I told him that I have someone else in mind, and it doesn’t matter whether he exists or not, but it’s definitely not him (Rami). There’s a lot I don’t remember, I sat there like a prisoner, I didn’t feel good talking to him and it made me sad to think of how the girls never love the boys who love them and vice versa…

When I left, I decided that I definitely did not agree with anything that happened!!! I know that I would never do anything that was THE DIRECT OPPOSITE OF WHAT I FEEL, whether it’s out of pity or obligation.

Whatever is inside me, whatever I have to give, I’m saving to give to a person I feel something for, or someone I know I want…

Yael, think about it a little, and it doesn’t matter if you only heard my side of things. Always remember that Idit really doesn’t love Rami.

Okay, enough about this, I’m sick of it and of the whole mess.

It was nice in our room. Too bad you didn’t come yesterday because I brought some great chocolate milk.

Why is someone I’m not interested in interested in me and vice versa?

Idit

GET WELL VERY VERY SOON

In June, right before the summer vacation between the tenth and eleventh grades, we all wandered together before going our separate ways to Yehiam and Shomrat. We went to the beach in Nahariya at night, and bought watermelons on the way.

We talked about the poem we learned with Shlomi, “Parting,” by Gabriel Priel, the poem he’d brought from the Theory of Literature course he was taking in Tel Aviv. Idit liked her paintings to have some connection to poems, but not as illustrations. It was something else. She had the sketch of a new painting that she called the black sketch. She called the painting “Parting,” like the poem:

She sat facing me and her eyes

Were brown from the coffee

Tortured from my body

As I tried to tell her

All the green things I had learned.

She surely did not listen:

She was trapped

In a cage of strangenesses,

Or walking down a street

That refused to meet

Another street.

Yet I know that her eyes turned briefly green,

Seeing a garden praying in the rain.

The dagger seemed thus to be pulled

From the brown valleys

And great stars

On the roads

Protected a small tranquility:

It will not reach me.

We rehearsed for the end-of-year play, and on one of those nights, I wrote in my dreams notebook:

Below every dream, I wrote about all sorts of things that really happened and were connected to the dream. I gave them the permanent title “Yosef’s Column.” Under that dream, I wrote:

Idit and I were talking about something today, and we bumped into Esti on the sidewalk. She said she was going to a rehearsal in Rami’s room. And without being able to explain it exactly, I felt as if something changed in Idit, that inside her, she suddenly turned toward Rami, and I felt terrible there, on the sidewalk, as if a huge hole had suddenly opened in the ground. That’s why this dream is totally accurate in terms of my feelings, when Idit answers, why not. I hope the dream isn’t a prophecy…

Idit was always painting, but that summer, in the Educational Institution, before we went back to Yehiam and Shomrat for summer vacation, her paintings began to speak, to spill off the canvas into the room. Then the hints began to add up, the signs began to add up, as if her love for Rami was only the last link in a chain that was larger than her, larger than Rami, larger than all of us.

Even though Idit and I wrote to each other constantly and were together constantly, it was difficult to know exactly when things happened, when words changed to deeds. She became an artist all at once. And it happened. At the same time. Rami and Idit became a couple.