I always wanted a gold record, and I always wanted to play Madison Square Garden. I already had my gold album. On February 18, 1977, we headlined our first show at the Garden. And it was sold out.

It had been four and a half years since I pulled up in front of the Garden in my cab to drop people off for Elvis’s show.

I had seen the Stones at Madison Square Garden—forged a ticket for that show, in fact. I’d seen George Harrison’s concert for Bangladesh at the Garden. I’d slept outside Macy’s in Queens to get tickets for that show. I’d seen Alice Cooper at the Garden. I’d seen Ringling Brothers Circus at the Garden.

Madison Square Garden was synonymous with success on a large scale. Playing there was big stuff. Really big stuff.

I was so anxious before the show that I took half a Valium. The idea that I might be sluggish? No chance. The adrenaline high was so strong on a normal night, and this was homecoming in a sold-out Madison Square Garden. I probably could have taken several whole pills and still have gotten up onstage and then run a marathon in record time. Shows like this were still new—I wasn’t yet used to the idea that we were this big.

Standing on the diving board is usually scarier than taking the dive, and sure enough, once onstage, I felt exhilarated. That first wave of force coming from people screaming and lights coming on is very powerful. Having multitudes of people focused on you and sending you energy creates an undeniable wave of force. That might sound like some sort of New Age concept, but the feeling is staggering.

The entire show carried incredible emotional weight. But by the second song, I was home.

I knew my parents were in the audience, and I couldn’t help chuckling about it: “Yep, that’s my boy—the one in eight-inch heels and lipstick jerking off a guitar onstage.” But I was proving something to them. They were wrong. This could be done. And I had done it.

You see? I am special.

And then a bottle came sailing out of the darkness and hit me in the head. I saw it at the last second and flinched just enough so it smacked into my head next to my eye instead of in my eye. The glass cut me. I bled for the rest of the show. In some ways it was cool, but I also felt hurt—not physically, but hurt that somebody would do that. And yet at the same time, I knew it wasn’t done maliciously. I’d seen the impulse before. Fans wanted to touch you in any way they could, and here was someone touching me with a bottle. Our road crew, as devoted as they were, found the guy and beat the crap out of him.

Still, it was the first time I felt vulnerable onstage. There was always a dark mass of people out there while I was in the spotlight, and now I knew I really could get hurt. For the first time it occurred to me that the fourth wall could be knocked down by them instead of by me.

We had about a week in New York around that gig at the Garden, and once again I was confronted with the fact that I didn’t have any real life outside the band. Most musicians I knew wanted to talk about equipment—stuff I could give a rat’s ass about. I thought there was so much more to the world, even if I was still learning what that could be. I liked to talk about music, but on a historical level, an emotional level—not a technical level. I spent a lot of time dissatisfied because I didn’t have friends to talk to about things that might be stimulating, educational, or enlightening.

As far as the women I hooked up with, I knew it wasn’t about deep conversation. I chose them because of what I thought other people would think—and because of what I hoped I could convince myself: I must be somebody worthwhile because this beautiful woman wants to be with me. It was all about bolstering my sense of self. Being with someone to make myself feel better always meant being with a woman others wanted, a woman others envied me for having. Thankfully, I managed to meet some women who, besides being beautiful, were also smart, funny, and well-read. But even with those women I had little to offer in terms of a relationship. I wasn’t open, and I wasn’t going to give anything of myself. So it was more or less two people trading services.

Though it was hard for me to articulate, all of this made me feel even more isolated than I already felt.

I remember one woman coming to my apartment and starting to get itchy for cocaine after a while. She apparently had a major habit. She began to get dressed to go out and score some blow. “I’ll come right back,” she said.

“If you leave,” I told her, “you don’t come back.”

You can be with somebody and still feel alone.

For me, actually being alone was worse. One evening I drove my burgundy Mercedes down to a hip restaurant and bar—one of those places that was known as a hangout. I pulled up to the curb near the entrance on Fifth Avenue and 11th Street and then sat in my car. I wanted to go in, maybe talk to some people, hang out. But I froze.

You can’t go in there on your own!

I didn’t know anyone. I couldn’t risk being in a situation like that. I couldn’t make friends. I couldn’t hang out. The Starchild? Yes, of course, he could. And even the version of the Starchild I could muster at parties put on by promoters or radio stations or our own management. Those were controlled situations. People in that context expected the Starchild; I depended on being the Starchild to interact with them. I depended on presenting a likable persona and hid my real self, the one-eared kid from Queens who still didn’t believe anyone could really like him and wouldn’t know what to do if someone did.

Who am I? Where do I belong?

I was supposed to be a big rock star, and there I was paralyzed in my car outside a restaurant, afraid to go inside. The contrast between how I was perceived and the reality of my situation could not have been more stark.

Who would believe this?

With a last look at the entrance, I pulled away from the curb, drove around the block, and steered the car back uptown to my apartment. I didn’t have the basic skills to function in a setting like that. Most people were petrified by the idea of going onstage. Not me. Whatever emptiness or insecurities I had waited at the side of the stage. I lived for those moments. I wanted the crowd to love me because I still hadn’t learned to love myself enough to get over the most basic social phobias I harbored offstage.

When are we going back out on the road?

Mercifully, we headed back out soon. And by March we found ourselves touching down in Japan in a Pan Am 747 amidst a Beatles-like furor over the band. In fact, it was the Beatles’ records we broke for attendance at the Budokan in Tokyo. The magnitude of our stardom in Japan was astounding.

We had arranged to pass through customs and immigration in full makeup and gear. We had it all with us on the plane and got ready when we were within a few hours of landing. But we arrived late, and the official who was supposed to be there to smooth everything along had already left. Without him, we had to remove our makeup before they’d let us in the country. After they verified we were the people in our passport photos, we did the quickest makeup job we had ever done and then walked out to find thousands of fans waiting outside. It was pandemonium. Once we got into our cars, people swarmed over them like locusts. I got nervous and claustrophobic.

“Smile,” Gene said calmly, through clenched teeth.

We spent the next two weeks attending lavish parties and making regular visits to Japanese bathhouses. The bathhouses employed women who seemed to grow extra hands and limbs once your clothes were off. If I could do to myself what they did to me, I would never leave home.

While in Japan I met with executives from Hoshino Gakki, the makers of Ibanez guitars. We sat in a boardroom and I explained my views on the sonics and aesthetics of guitars, which led to my first signature model. Having my own guitars sold in music stores around the world was a milestone for me—and any musician.

After the last show, we flew back to Los Angeles. There we learned we’d been named the top band in America by the Gallup poll—over Aerosmith, Led Zeppelin, and the Eagles, among others. Soon, magazines were publishing similar results from readers’ polls. In Circus magazine we won a head-to-head poll versus Zeppelin. Now, I had a high regard for what we were doing, but I wasn’t crazy—I didn’t see us in the same league as Zeppelin. The same publications also ran votes on readers’ favorite players, and Ace and Peter both came out on top of some “best guitarist” and “best drummer” polls, fueling the increasing gap between their self-image and their actual abilities. If only Circus readers realized they were barely sentient beings most of the time who didn’t care and were often either too fucked up or too inept to play their parts on recordings without great effort or a nameless ringer filling in for them. I figured if we were going to disregard the critics who called us hucksters and dismissed our music, we also had to dismiss the people who called us virtuosos. Peter and Ace didn’t agree. The press reinforced what they wanted to think: that they were world-class musicians. Of course, Ace could really have been one, but he was killing his talent—and his body and brain—with booze and drugs. And Peter? From Destroyer on, what the band wanted to do pushed the limits of his abilities or simply outstripped them.

We had a few weeks off in L.A. before we went to New York to start recording yet another album. One night I ended up going out with Lita Ford, who was then the guitar player in the Runaways. Lita and I had some fun times together. She was only nineteen, but her band had just released their second album and were about to head off for their own tour of Japan. The two of us went to a club called the Starwood for a show. The opening band, the Boyz, featured George Lynch, who went on to fame in the band Dokken. The Boyz played a cover of “Detroit Rock City.” The second band was called Van Halen. I was impressed. They had another show the next night, and I made Gene go with me to see them.

Near the end of Van Halen’s set that second night, Gene got up and disappeared. Little did I know, he’d gone backstage and spoken to them about taking them into a studio to record a demo. He never told me. He didn’t mention it when he returned to his seat; I found out only later. It was funny, because I always thought of Gene as the one member of the band I could count on, and yet he still did secretive things like that. It was that old impulse of his—and he never felt the need to explain any of what I saw as sneaky or dishonest behavior.

During that time in California I also met and started seeing Cher’s sister, Georganne LaPiere, who was then starring in the soap opera “General Hospital.” Georganne was extremely smart—a member of the high-IQ society Mensa—and I loved talking with her. Georganne and I saw each other off and on for more than a year, though after a while I told her I planned to see other people as well—there was no dishonesty about it. I realized phone relationships could go on forever. You talk to somebody, have a nice conversation, and then, when you say goodnight, you go off and do whatever you’re going to do.

At the end of the time in L.A., I flew to New York. The song “Love Gun” came to me in its entirety on the flight—melody, lyrics, all the instrument parts—absolutely complete. It was amazing—and rare for me. I stole the idea of a “love gun” from Albert King’s version of “The Hunter,” which Zeppelin also nicked from for “How Many More Times” on their first album. By the time the plane landed, I was ready to record a demo.

When I got to New York, I called a drummer I knew and went almost immediately to Electric Lady to record the song. By this point I didn’t need to do demos in less lavish studios—I could do them in top-end studios, and Electric Lady was my favorite. I used the same equipment and tape that other bands cut masters on. That worked out to be as much of a curse as a blessing. Sure, the demos sounded great. But with using quality studios for demos came the risk of demo-itis. You get so locked into the version you record as a demo that you lose all flexibility when it comes time to record the track. You’ve worked out all the parts, and it’s hard to erase them and let other people have creative input if they veer from the version you recorded on the demo. Then you’re stuck recording a stiff version of the thing you already did—it robs the final recording of spontaneity. You’re less open to suggestions for change because you already have a fully realized concept. Eventually, in the late 1980s, I stopped doing demos for all those reasons.

The funny thing about “Love Gun” was that even though the album version was recorded as a facsimile of the demo, when we went to cut the album version, Peter couldn’t play the kickdrum pattern on the song. Once Peter cut the track, we had to bring in another drummer to play the extra kickdrum beats Peter couldn’t.

We recorded the album at the Record Plant, another iconic New York studio. It was up near Times Square in what at the time wasn’t a great neighborhood. When you entered the place at the ground level, the receptionist was sitting behind a glass window and had to buzz you in through a locked door. The window had shutters, and once through the locked door, you saw that the reception area was separated from the hallway by another locked door. I can’t tell you how many times I left the studio to take a break and walked into the receptionist’s little office. She would close the shutters and lock the door and say, “Oh, Paul!” I didn’t fool myself into thinking I was the only one, but I was one. And it was terrific. Sure beat a coffee break.

During our stay in New York, Gene came up to Bill’s office and played us finished demos by a band called Daddy Long Legs—it turned out that was a name he came up with to replace their original one, Van Halen. Bill and I listened intently and later spoke—without Gene—and agreed to pass on getting involved with them. Not because they weren’t great. Not because they didn’t have enormous potential. We passed to protect KISS, which needed our daily focus to continue building on all fronts. Gene’s wandering eye was clearly a potential risk to all we had accomplished and all we were working toward.

For the Love Gun tour, which began in Canada in early July 1977, after the album was released, we had a private airplane for the first time. We’d flown private only one time before, when because of a scheduling conflict we had to take a tiny Learjet to get in and out of some out-of-the-way city. This was different. This was ours. It was a Convair 280, a propeller plane, filled with odd furniture—almost like a flying junk shop. The pilot and copilot were Dick and Chuck, and our flight attendant was named Judy.

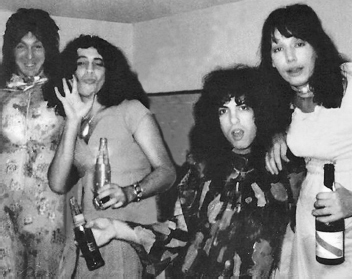

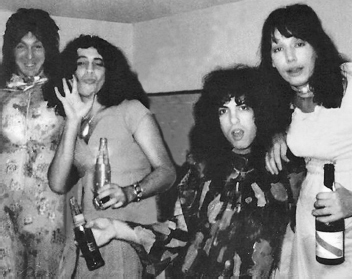

They showed up in drag and handed me a dress, in honor of my birthday; left to right: Peter, Gene, Me, Ace. Lincoln NE, 1977.

Dick and Chuck fought regularly and often yelled at each other in the cockpit. “You asshole!” “Fuck you!”

It wasn’t very reassuring.

Once, at the end of a flight, we landed, got to the end of the runway, turned around, and immediately took off again. They had put us down at the international airport rather than the private airport. Another day I saw flames coming out of one of the engines midflight. I told Judy to bring Dick back to see it. He came back, looked out the window, and said matter-of-factly, “Don’t worry about it.” Then he returned to the cockpit. The whole operation was an accident waiting to happen.

The tour itself, however, went gangbusters. We had to add dates in a lot of markets and recorded another live album, Alive II, along the way. It seemed like a good idea: we’d done three studio albums and a live album, and then another three studio albums. Why not another live album? The problem was, we had to fabricate a KISS show for the album because we didn’t want to repeat material from the first live album. That first one documented a standard set. The second one couldn’t because a lot of those songs from the first three albums were still staples in our show. So now we had to create a KISS show that didn’t really exist—with the dynamics of a real show. Even so, it didn’t seem like a big deal since we had a lot of great stuff— “Detroit Rock City,” “Love Gun,” “God of Thunder.” And once again we enhanced the ambient quality of the live recordings so they replicated the bedlam of an actual show. The onstage explosions caused compression in the microphones, so again we used recordings of cannons to make them sound right. And for the back photo, we decided to take a shot during sound check at the San Diego Sports Arena with all our effects shot off at once—just blast the entire arsenal and have us all up on the hydraulic lifts. That never actually happened all at the same time during a show, but it was an authentic documentation of the bombastic feel of the experience.

The second problem with Alive II flowed from the first. Using only songs from the second three studio albums, the new live album took up just three sides of a double album, not four. What were we going to do? We decided to add a side of studio tracks. I wasn’t keen on the idea. We recorded the tracks at the Capitol Theatre in Passaic, New Jersey, to give them a live feel. I had “All American Man,” which I’d written with Sean Delaney, but overall, the songs we came up with just weren’t great. “Anyway You Want It” was a Dave Clark Five song I’d always loved, and Gene loved it, too. The original 1964 version is cataclysmic—just huge. Ours didn’t come close, but we needed to fill up that final side of the record.

Ace didn’t play on any of the studio tracks except the one he wrote, “Rocket Ride.” Instead we had to use Bob Kulick, who had auditioned for the band during the cattle call back in 1972 and with whom I’d remained friends.

As the tour continued, we flew on with Dick and Chuck fighting in the cockpit. During the time Uriah Heep was opening for us, I constantly made eye contact with their keyboard player’s great-looking girlfriend. I found out her name was Linda and the day after the band left our tour, I called our tour agent and said, “Track that girl down.” The next day she was back on the tour, now traveling with me. This was rock and roll.

In Houston someone showed me a 1958 Flying V guitar, which was something I really wanted. It even had its original case. I asked how much he wanted for it. “Thirty-six hundred bucks,” the guy said.

“Come on, that’s a lot of money.” He didn’t budge. I bought the guitar. I had caught the guitar bug again.

In California someone told me about a guy who had a sunburst Les Paul for sale. I paid $10,000 for it. It seemed like a fortune at the time, but it ended up on the cover of the bible of sunburst guitars—The Beauty of the ’Burst—and is valued at as much as a million dollars now. (Best of all, that guitar is still known as the Stanley burst, even though I no longer own it.) By the end of the Love Gun tour, I had nine premier examples of guitars I loved—including the ones I’d already bought.

The demand for KISS concert tickets continued to rise through the year. And being onstage continued to suspend everything around me. Performing provided pure escapism and joy and elation. In my everyday life, I could never free myself of my insecurities, and the increasing rancor inside the band left me feeling more isolated than ever. One night I even decided I should try the rock star thing of breaking up a room, but as soon as I started breaking things, I stopped.

What did I do that for?

The room’s messy now.

This is my room—now I have to clean it up.

But as I walked up the steps to play the show each night, I shed all problems at the bottom of the stairs.

I needed the crowd to love me. Nobody else did. Not even me.

It can be very lonely walking offstage when you feel like that. When so much seems to be missing from your life. By December of 1977, when we got back to New York, we had sold out three more nights at Madison Square Garden. After the first two gigs, the other guys met up with family or friends; I found myself sitting alone at Sarge’s Deli on Third Avenue and 36th Street eating a bowl of matzo ball soup. On the one hand, now that I was a rock god playing a block of shows at MSG, I assumed I had succeeded in making people envy me and wish they had been nicer to me. But on the other hand, there I was having soup in a deli by myself.

That was a harsh reality to deal with.

After the final MSG show, Bill Aucoin threw a party at a swank townhouse. I flew in a girlfriend from Detroit. Santa Claus was at the party. And I had never seen so many lobsters in my life—hundreds and hundreds of them piled up on platters. They must have cleaned out the ocean for weeks. We still didn’t understand that we ourselves actually paid for such things.

George Plimpton and Andy Warhol came to the party. It was always interesting to see people from other scenes like that—artists, writers, entertainers. Oh, that’s George Plimpton. But I didn’t function well except in the most socially controlled situations. I didn’t want to risk getting shown up. I was too self-conscious.

I locked myself in the bathroom with a woman who worked at a radio station. When we finished, we straightened our disheveled clothes and I went back out. Andy Warhol approached me and said, “You should come down to the Factory sometime and I’ll do your portrait.”

I’m not cool enough to hang around people like that!

I never went. Big regret on that one.

After playing three nights in a row at the Garden, I knew one thing: what I had thought would fix me, had not.

If all these people look up to me and see me as special and a star, shouldn’t I feel that way?

Maybe in theory. Maybe while I was onstage. But success and fame and the change in the way other people perceived me hadn’t erased whatever was wrong behind the mask. I had reached what I was after, and it wasn’t the answer. Whatever was missing was still missing. The question was, what was missing? What was wrong?

And just then, as the Love Gun tour wrapped up at the beginning of 1978, a funny thing happened. At what seemed like the peak of our popularity—and when being onstage provided the only respite from my emptiness and my nonexistent home life—we stopped touring. In part, it was because we simply couldn’t. Ace and Peter were deeply into drugs and alcohol and alternated between hostility and incoherence. When they weren’t incapacitated, they caused headaches for everyone around them. We weren’t speaking to each other. We couldn’t stand each other.

We wouldn’t play a gig for more than a year.

What do I do now?