Even though drawing was my ticket into Music & Art, I wasn’t thinking very seriously about trying to make a career of art. Which turned out to be a good thing, because it was sobering to show up at school in the fall of 1967 and see not only so many people who were as good as I was, but also plenty who were clearly better.

I had pursued art primarily because there was no school for aspiring rock stars—art was a backup plan. No longer. I knew now it was music or bust. Even so, when I headed off to school each day, my musical aspirations stayed behind, carefully stashed in my purple bedroom. Though I never told fellow students at school about my aspirations or tried to switch to the music curriculum, I was aware that Music & Art students had an impressive track record of making a musical impact—and not just on Broadway and in orchestras. A band called the Left Banke, who had a big hit with “Walk Away Renee,” were recent grads. As was the brilliant singer-songwriter Laura Nyro. Janis Ian, who had just had a hit with “Society’s Child,” was still enrolled when I arrived.

One day Matt Rael’s older brother, Jon, came around to see me. He’d already had several bands and we all looked up to him. His first band was influenced by the Ventures—surf music—but these days he was leading one called the Post War Baby Boom that sounded like some of the stuff coming out of San Francisco—a hippie take on folk, blues, and jug band sounds. They had a girl singer who took leads on some songs—that stuff was a bit like Grace Slick’s first band, the Great Society. And the Post War Baby Boom actually played gigs.

Out of nowhere, Jon asked me to join the band. They needed a rhythm guitar player. My mind raced: why hadn’t they asked Matt, who at that point was a better guitar player than I was? Maybe because I’m in high school and Matt has another year of junior high? Is Matt going to be pissed?

Holy shit, a real band! This is huge!

I didn’t hesitate for another second. I said yes. Next thing I knew we were rehearsing in the same basement where Matt and I had previously practiced. We worked on an up-tempo cover of Gershwin’s “Summertime.” I also worked out a version of “Born in Chicago” by the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and even sang lead vocals.

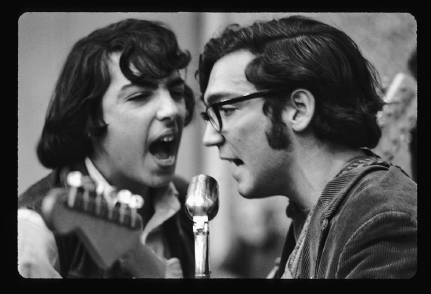

Playing Tompkins Square Park in the East Village with “The Baby Boom.” I’m on the left, at age fifteen, Jon Rael on the right.

Everybody else in the band was at least two years older than me, which, at that age, seemed like a lot. What didn’t occur to me at the time was that they would graduate high school at the end of that school year. But in the short term, I was all in. We had a few gigs in “our” new lineup, and then I suggested we try to get a recording contract. I said we should have some pictures taken—and I knew just who to call. That summer of 1967 I’d spent two ill-fated weeks at a summer camp near the Catskills Mountains. Or at least, it was supposed to be a summer camp. It turned out to be a scam—some guy got a bunch of parents to pay him to have their kids come up to his farm, camp out, and, it turned out, help him tear down an old barn. He called it a work camp, implying that his program represented a chance for city kids to work on the land. In the end, though, it had been kind of fun, and I had become friends with one of the counselors, who were as duped as the campers. His name was Maury Englander, and he was now working for a famous photographer in Manhattan.

Maury had access to the photographer’s studio whenever it wasn’t being used—that was one of the perks of the job, since Maury was in the process of becoming a photographer himself and in fact would be working for magazines like Newsweek less than a year later. So I called him, and we arranged to go into the studio one weekend and have Maury take some promo shots. Maury was pretty wired-in politically as well, and we parlayed the photo session into a few gigs playing parties for various antiwar organizations in early 1968, as protests against the Vietnam War were picking up steam.

Club gigs were tough to come by, because they still wanted Top 40 cover bands for the most part. We played a lot of our own songs, and the covers we did were not the sorts of songs at the top of the charts. I arranged an audition for us at a place called the Night Owl; I had read that the Lovin’ Spoonful had played there, and the Spoonful’s jug band roots and good-time sound weren’t so far off from what the Post War Baby Boom was trying to do. But at the audition, the guy who was making the decision walked out while we were still playing. We didn’t get that gig.

Despite the slow-going, I wanted to succeed and worked at it ceaselessly. Eventually I managed to pass some materials to somebody with an in at CBS Records, and an exec from the label called me. “If you guys can play as good as you look, you’ll be great,” he said. He was referring to one of the studio shots Maury Englander had taken of the band.

Before the guy ever saw us in person or heard us, he arranged for us to record a demo at CBS. I wrote a song for us to record called “Never Loving, Never Living,” but I was too shy to play it for the band until the day before we were supposed to cut it. And then our female vocalist decided to go for a swim in the fountain in Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village the night before, and she caught a cold and lost her voice. When we showed up in the studio the next day, my first time ever in a real recording studio, she couldn’t sing.

To top it all off, the CBS exec told us he wanted to rename the band the Living Abortions. The demo never got finished.

Meanwhile, at Music & Art, despite keeping to myself, the chance to see girls in T-shirts and no bras—another advantage of the lack of a dress code—was more than enough to get me to school every day. But I soon found I was at odds with myself and everybody else. I looked hipper than I really was because of my hair and clothes. But my hair was blown out in part for one very specific reason, and I felt intimidated by the kids I thought were genuinely hip. As I slowly learned, covering my ear didn’t change anything. Like everything else in life, ultimately it wasn’t about what other people saw, it was about what I knew and what I felt.

One day at school, one of the cool girls called out to me. Victoria was curvy and blond, with disarming blue eyes. It was well known that she had the coolest friends, in and out of school. I was wearing a leather jacket with fringe, which was a hip look at the time, and a look not many people were rocking yet, even at Music & Art. “Hey, fringe!” she said.

I went over to talk to her and somehow mustered the courage to ask her out. It was like an out-of-body experience—somebody was talking, and it was me, but I felt totally disconnected because it was such a leap into uncharted territory. She said yes, and I walked away in a state of exhilaration and terror.

We went to a concert at the Fillmore East. But when we got there, she knew tons of other people in the audience. We wound up sitting with her friends. I was immediately intimidated because they were hip, and I was an uptight kid from Queens. They started passing a joint. I took a hit each time it was passed to me, and I got pretty high. Soon I was talking nonstop, until Victoria said, “What the hell are you talking about?”

That shut me up for the rest of the show.

After the concert we went back to her parents’ apartment. I was still really stoned and also paranoid because Victoria had seen a chink in my armor and questioned my coolness. I ended up talking to her dad—and continuing to talk to him long after she had slipped off to her room and gone to bed. I eventually slithered out of the apartment feeling like a complete jerk.

From then on in school she snickered whenever we ran into each other. I don’t think she meant to be mean, but she wasn’t laughing with me.

Another girl I saw briefly lived in Staten Island. She was half Italian and half Norwegian and lived in an Italian neighborhood. She was hooked on speed—between me being a bit stocky and her having no appetite, I often got to eat her lunch, which her mom lovingly prepared, not knowing who would actually end up savoring it. The first time I met her mom, she seemed to like me; the next time I went over to her house to pick her up, I wasn’t allowed into the house.

“I can’t go inside?” I said to the girl.

“No, my mom thought you were Italian, but she found out you’re a Jew.”

That was my introduction to the wonderful world of anti-Semitism.

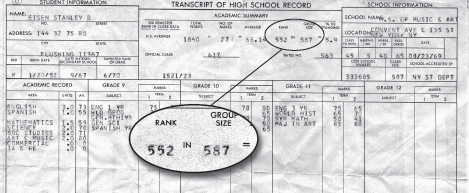

After a while, the double-whammy of my insecurity and my inability to hear what was going on in class had me falling into the same old pattern in school of getting lost, getting frustrated, isolating myself, and eventually cutting school as often as I could get away with it. I knew how many days I could be absent, how many classes I could miss, how many times I could be late—and I used them all to their fullest. Those were the school statistics that mattered most to me.

My rank: 552 out of 587 students. If you can’t graduate at the top of your class, distinguish yourself by graduating at the bottom. It’s a miracle they let me graduate at all.

I became a ghost—hardly ever in school, and when I was there, nearly invisible. I sat in the back of my classes and barely spoke to anybody. Once again, I was living in self-imposed exile as a result of my defensiveness and social anxiety. Once again, I was beginning to shut down. Life was poisonous and desolate. My sleeping problems returned. Once again, I would wake up screaming from the familiar nightmares, sure that I was dying.

I’m alone on a floating dock, far from shore, surrounded by darkness . . .