The massive Thompson Graving Dock viewed from the deck of Olympic. The largest dry dock in the world, it was named after the chairman of the Harbour Commissioners.

Of all the cities and towns in Ireland, Belfast has the least interest in any history before the Act of Union. She is enormously occupied with her present, enormously and justly proud of what her citizens are and of what they have accomplished. But what should most concern all Ulstermen and all Irishmen is the future of Belfast—for with it is inextricably bound up, for good or for evil, the whole future of the Irish nation.

Stephen Gwynn, The Famous Cities of Ireland, 1915

To further understand Titanic and the people who built her it is important to visualize what Belfast was like in the first decade of the twentieth century, what the work opportunities were for ordinary people, what underpinned the simmering political situation, and, above all, what Belfast’s status was as a highly specialized industrial capital.

In 1911 there were rumblings of revolution in the air. The Siege of Sidney Street had taken place in January in the East End of London, with Home Secretary Winston Churchill arriving in person as the police shot it out with Russian anarchists armed with “broomhandled” Mauser pistols; and the abortive revolution in Russia of 1905 had not disappeared from people’s minds, in particular the minds of politically motivated workers. But to counter this, opportunities for work were expanding, not least in Belfast.

Things had happened fast. Belfast had started life as a medieval castle built on a strategic headland. It became a town proper only at the beginning of the seventeenth century, when it was developed by its English owner, Arthur Chichester. By the beginning of the nineteenth century the still-rural Belfast had a population of about 25,000, and this increased to only 70,000 over the next fifty years. But by 1911 the population had grown enormously, to nearly 400,000. The advent of industry, and especially the shipping industry, was the reason for this. As mentioned in chapter one, William Ritchie established a shipyard for wooden windjammers in 1791, and the first iron ship, the Countess of Caledon, a Lough Neagh steamer, was constructed there by boilermakers William Coates & Son in 1838.

Belfast was now the biggest city in Ireland—far bigger than Dublin, which still based its economy on land and trade—and this was in a country whose population had for half a century been in decline as a result of the potato famine and consequent emigration, largely to America. The scale on which the city was booming eclipsed even its rivals in northern England, but it had its own internal tensions. Arthur Chichester had peopled his settlement with English and Scots, all Protestant and Presbyterian. The native Irish, all Catholic, lived mainly to the west of the town. Throughout the first two centuries of its life, Belfast was both radical and democratic. Religious tension was unknown, despite earlier attacks on the Catholic Irish by the Elizabethan explorer Sir Walter Raleigh and the Puritan lord protector Oliver Cromwell. (But the history was to add up, of course, and the way the English dealt so brutally with the Great Famine of the midnineteenth century scarcely helped to create goodwill.)

By the time of the first insurrection against English rule in 1798, Belfast had already set foot on the path that would lead to its commercial future, and the production of linen (on the Antrim side of town) and the production of ships (on Queen’s Island) were establishing themselves as its defining industries. Indeed, heavy investment in the recently perfected mechanized spinning wheels would quickly efface the cottage-industry handicraft of the rural vicinity, and by 1900 the linen industry employed 35,000 workers within the city.

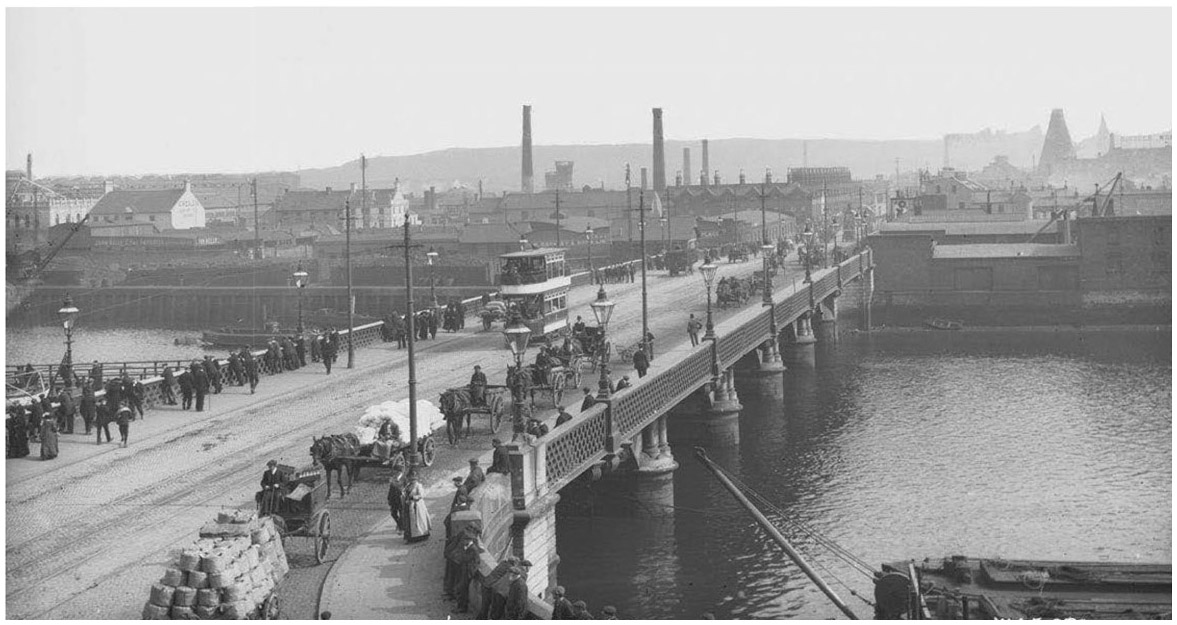

Queen’s Bridge, Belfast, which joins the town center to Queen’s Island across the River Lagan, c.1911.

Shipbuilding at the time did not employ as many workers as linen, but that soon changed. Throughout the nineteenth century the shallow waters of the city were systematically dredged, and by the time Harland & Wolff came into its own, the depth of the waters of the River Lagan and the Musgrave Channel meant that larger ships than ever before conceived could be built and floated with ease.

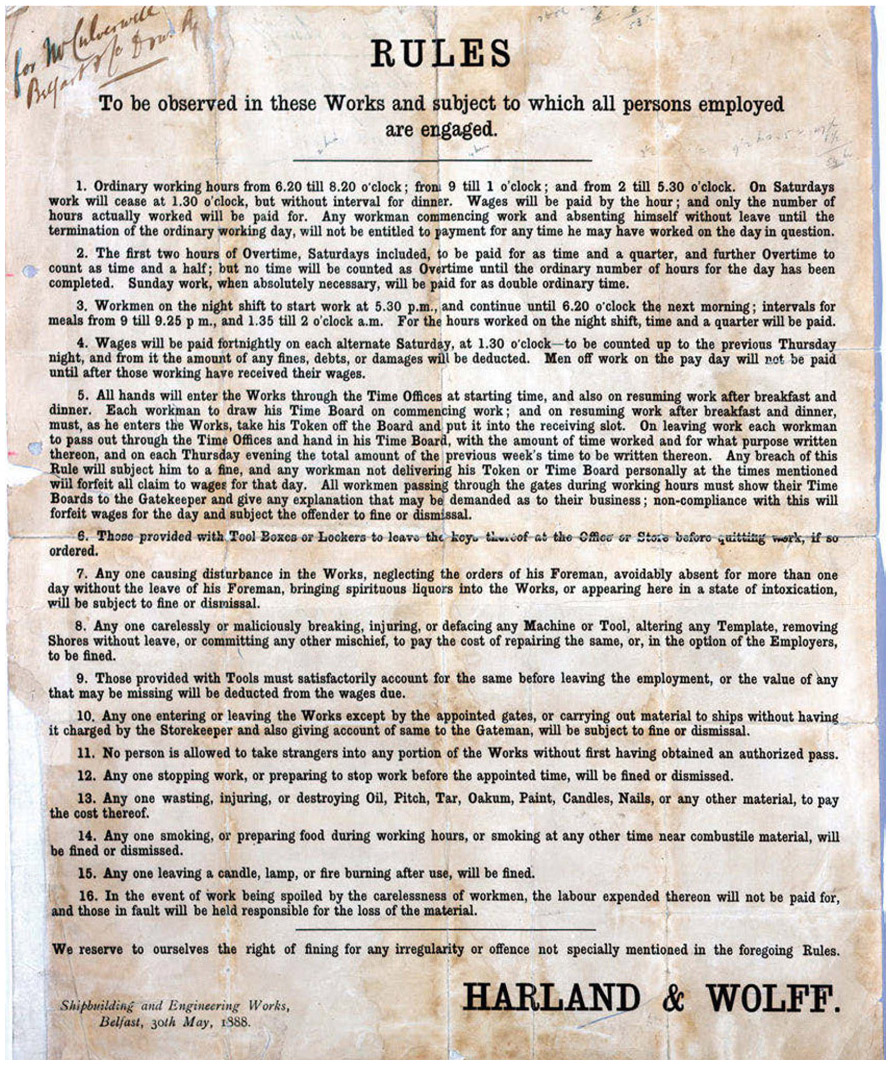

Managing the massive workforces of the industrial age required rigid structures, strict discipline and constant supervision. Time was money and men were machines. The thousands of men who entered the shipyard each day were broken down into manageable crews, each led by a foreman, or “hat.” Hats, named after the bowlers they wore, which defined their status, ran their crews with rods of iron, barking their instructions through megaphones, constantly on the alert for shoddy workmanship, and with the power to dock wages for any slacking.

But shipbuilding and linen were not the only industries to flourish. Manufacturing chemical dyes, rope-making, distilling and tobacco curing followed, and as the town prospered, so it grew. It quickly became a place of international importance, and the buildings that sprang up reflected this. In 1888, Belfast ceased to be a mere town and was formally incorporated as a city. The boom attracted tens of thousands of rural Irish Catholics in search of higher wages and a more predictable income than the land could afford. In 1784, Catholics made up 8 percent of the town’s population. By 1911 that percentage had trebled.

The Belfast bourgeoisie lived in the districts centered on Malone Road and Botanic Avenue. By contrast, the shipyard workers lived in crowded redbrick terraces close to Queen’s Island. But alongside the class divide existed a sectarian divide. Prejudice—blinkered, selfserving and divisive as it was and continues to be—bore its usual fruit. Orange Day (July 12), marked by a Protestant march to honor the victory of William of Orange over the Catholic James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, saw sectarian battles even in the early decades of the nineteenth century, and by the 1850s they had become unmanageable. Territorial battle lines were drawn up: the Catholics occupied the southwest of the city and left most of the rest to the economically dominant Protestants. And there were further frontiers—separate schools, for one thing; and a division of labor, for most of the Catholic workers were unskilled, or at least excluded from skilled employment. It was small wonder that the Protestants, out of self-interest, would associate themselves with the Unionist cause, and that the Catholics, wishing to be part of the socio-religious majority of Ireland in the hope of a fairer deal, joined the Nationalists. By 1911, the year of Titanic’s launch, Dublin was still the center for the British administration of Ireland; but the focus and fulcrum for loyalism to the crown was Belfast, vastly more important in every way, but above all economically, than any other conurbation in Ireland. All other arguments apart, it is no wonder that Great Britain didn’t want to let Belfast go to any Irish Republic.

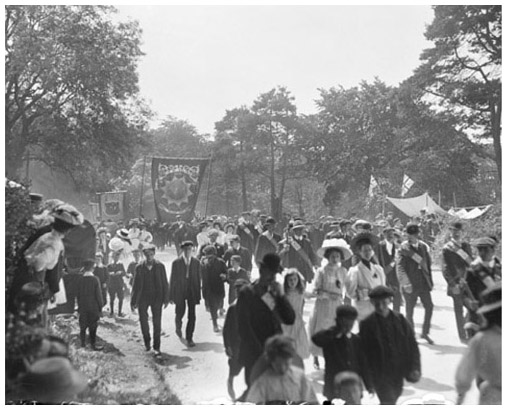

An Orange Day parade in Belfast about the time of the construction of the Olympic-Class liners.

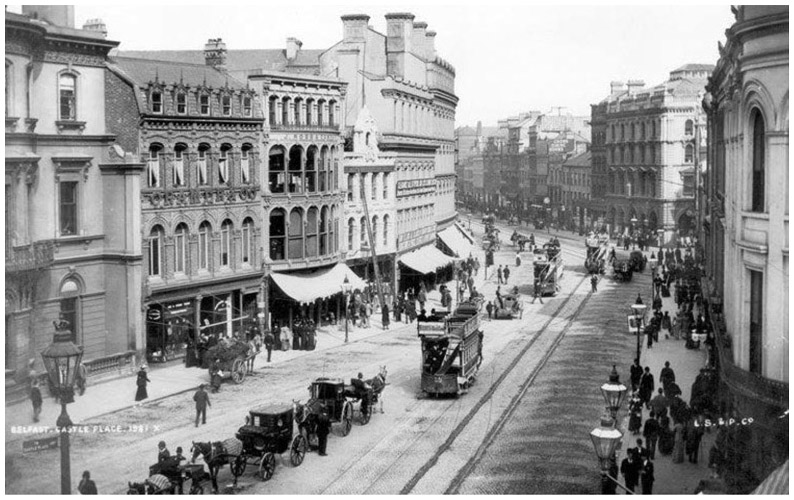

Castle Place, central Belfast, c.1905. The city is already a thriving urban development—notice the horse-drawn cabs and trams.

So, we have a copybook Victorian boom town—smug, materialistic and rich. Belfast had electric trams and big new public buildings in the various neo-Gothic, quasi-Greek, vaguely Palladian and over-iced Georgian styles favored by the Victorians. Underneath the affluent appearance, social differences simmered. The middle-class suburbs grew and prospered, fed by the tramway, but the working class, which powered the city, found that its housing scarcely increased at all. Despite the prosperity, the gulf between wealthy and poor increased, and the living standards of the poor (predominantly Catholic) actually declined. In the midst of this, the Protestant skilled working class and the Unionist leaders of industry (including Harland & Wolff), mutually threatened by what they saw as the specter of Irish Nationalism, drew together against the prospect of Home Rule.

Titanic set off from Southampton on her maiden voyage the day before the Third Irish Home Rule Bill came before the House of Commons on April 11, 1912, and it’s worth bearing in mind the political melting-pot that formed the backdrop to her construction. So ludicrous did partisanship become that her alleged (and totally false) ship number, 3909 ON, was deemed to be a code: in mirror image, and with a good dollop of imagination, this cipher could be read as NO POPE—a sectarian slogan of the time. Paradoxically, Titanic herself became a symbol of Unionist hubris.

Even though Belfast was a recognizably modern city, just 5 miles outside it rural life prevailed much as it had a hundred years previously—a world of horse-drawn wheel-less slide-cars, of men fishing from coracles, of humble little shops, of hand-looms worked by men in their own tiny kitchens, of harvest-homes that wouldn’t seem unfamiliar to a fourteenth-century serf. The villages, formed of low thatched cottages strung along an unmade main street, hugged the land as if they had grown out of it. But this was a society that hadn’t long to live.

Back in Belfast, anything up and coming was in the hands of the rich. Cars, for example, were hugely fashionable, as was the clothing in which to drive them. A Ford Model T, in production from 1908 until 1927, cost about $550 in 1910 (the equivalent of about $21,700 today), but the price decreased over subsequent years as profits caught up with production costs. For those with more modest incomes, there were bicycles, but in 1910 a new bicycle would set you back £12—six weeks’ wages for a skilled worker. Then there was air travel, still in its infancy, but proved possible in principle, and which in two decades would be properly grown up.

In their limited time off, workers enjoyed the usual recreations of breeding poultry and terriers, whippet racing and social drinking. Given their long and arduous working day, it’s a wonder they had the energy to do more than eat and sleep. Harland & Wolff, though, were good employers, paid a fair wage, and treated their workforce strictly but decently. However, Victorian class values still prevailed, as recounted by a former employee: “Everything was controlled. The bosses kept an eye on everything, every minute of the day. You couldn’t sit down without someone shouting at you. It helped create a real us-and-them mentality. If you were a boss you were a part of the system, and if you were a worker, we was all in it together.You have to remember this was tough, dirty, dangerous work, so a bit of spirit was important to help you get through the days.”

Fines were imposed for all sorts of offenses—smoking, loafing (idling), and even playing football with rivets. One of the commonest offenses was “boiling can”—that is, making tea at unauthorized times and in unauthorized places, as for instance when boiling water up on one of the portable rivet furnaces.

Fines were expressed in the Fines Books either in cash terms, or in terms of paid time forfeited. For example, on December 9, 1910, a fitter’s assistant called John Henry was fined a quarter of a day’s pay for “dropping links from Gangway No. 401 [i.e., Titanic].” Three days later an apprentice fitter was docked half a day’s pay for “boiling can at 8:10 a.m.,” although this was only ten minutes before tea was officially allowed to be brewed, so it’s easy to see how strictly the rules were enforced. Bad timekeeping was a frequent offense and cost the offender 2s 6d (the equivalent of about $16 today). Playing cards or football during working hours was similarly punished. An apprentice plater called William Vance was fined 2s 6d on June 9, 1909, for “destroying hammers shaft”; and an apprentice driller called William Robson was fined 1s on February 10 that year for “loafing and going down gangway before time.”

The rules of the yard were absolute, and they covered every aspect of the day. The first morning of course I had to respond to a call of nature and I didn’t know where to go, so one of the other apprentices took me to the lavatory block. This was up a sort of spiral staircase and there was a little office at the top with a clerk in it, and he took your number. Everyone had a number, which was stamped on a little piece of wood called “the board,” and you kept the board, which was about the size of a cigarette packet but not as thick, in your pocket. The clerk either took the board or took your number. He then explained the rules, which were very simple, and I can remember exactly what he said. He said, you are allowed seven minutes in the forenoon and seven minutes in the afternoon, and that was it. Any extension of that time would either need a doctor’s note, or you’d be fined. The term “minutes” came to mean “lavatories,” and in fact if you were looking for someone you might be told, he’s away to the minutes, and you’d know what was meant.”

Former shipyard worker

And what of women workers during this time? Let’s take a fairly typical example. Elizabeth Sproule was eighteen years old when she married Robert Murphy then an apprentice riveter at Harland & Wolff, on Christmas Eve, 1880. They’d grown up together on the same street, and their first married home was a near-hovel in Murphy’s Court, an area so grim that the census people didn’t care to visit it. They had at least six children, though three died in infancy, typical of the time.

A worker is dwarfed by the massive looms in one of Belfast’s linen mills. The manufacture of linen was second only to shipbuilding in the city’s industrial make-up.

A common practice among working men was to take their wages, paid in cash at the end of the week, and make straight for the pubs, where a pint of Guinness cost the equivalent of three cents. Whatever they didn’t spend there, and for many that wasn’t much, had to pay for food and rent. Elizabeth was lucky—her husband was a teetotaler, so she never had to endure the miseries many other women suffered. Of course, the man of the house always got the lion’s share of any food so that he’d have the strength needed for his heavy work at the shipyard. Children got the next portion, and the mother had to make do with whatever was left. In the poorest families the womenfolk were frequently malnourished.

Elizabeth Sproule found work in the linen mills, where women workers dominated, and many took their babies with them. Stories abound of pregnant women walking to the mill, putting in a twelve-hour day, walking home again, giving birth in the night, and going to work with their newborn the next morning. Elizabeth Sproule may have been luckier than some, but it was in the linen mills that she picked up tuberculosis from the foul air, and it killed her in 1897, when she was thirty-five years old.

At a time when workers’ interests were at last being recognized and focused on through the work of the philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, it’s unsurprising that some workers interested themselves in politics. Others took up literature and the natural sciences. One worker in particular, Robert Bell, was a keen amateur geologist and mineralogist, the discoverer of several species of fossil mollusks, whose contribution to science was such that several examples were named after him.

These, then, were the social and political circumstances in Belfast surrounding Titanic’s birth. The city was like a tectonic plate where the old world met the new, and the reverberations of that meeting would have a profound impact.

In 1907, White Star implemented a change that had a serious effect on employment and social structure in Belfast: it changed its port of departure from Liverpool to Southampton. Cunard would follow suit after the First World War.

Southampton had many clear advantages over Liverpool. For a start, it was a natural deep-water port, and its double high tides saved ships long and expensive waits outside the harbor. (The P&O Line and the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company were already established there.) It was also far closer to London, with a direct rail link to the city, and only a short distance from France, where passengers bound for America could be conveniently picked up at Cherbourg. In addition, it was an easy voyage on to Queenstown, where Irish emigrants embarked. Of course, the new Trafalgar dry dock, completed in 1905, was a special enticement for shipping companies.

Although White Star retained its main office in Liverpool, its operational center effectively moved to Southampton; and where White Star went, Harland & Wolff followed, with ancillary maintenance and outfitters’ workshops. Unemployment, a problem in Southampton in the early years of the twentieth century, disappeared. The town boomed.

The departure port for New York was moved from Liverpool to Southampton early in the twentieth century, as the latter was far more convenient for connections from London and for the transatlantic liners’ interim ports of call, Cherbourg and Queenstown. The London and South-Western Railway was responsible for the link between the two English towns, and this Thomas Cook poster presents it as a gateway to the Continent.

But it wasn’t all plain sailing. London & South-Western Railway (LSWR), which had poured money into the town and renovated the South Western Hotel in 1882, was quite happy to invest heavily in the new port, and White Star was able and willing to provide employment opportunities for crews, just as Harland & Wolff could hire construction workers. But the companies needed longer quays and deeper docks, as well as larger and deeper channels for the massive new liners. They also needed wide expanses of water for the tugs to swing the ships around.

The River Itchen and the quays were controlled by the Harbour Board, and when White Star’s local manager, Philip Curry, wrote to its members in December 1908, he had no reason to expect any objection to his request for improvements to facilities.

It is with pleasure that we have to inform you that with the object of bringing their Southampton–New York service up to the highest standard of efficiency, and of developing to the fullest extent the traffic via Southampton, the management of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company Limited (White Star Line) are now having built at Messrs. Harland & Wolff’s shipbuilding yards at Belfast two steamships of the highest class, which will provide every attraction and comfort for travelers . . . and which will much exceed in tonnage any vessels now afloat or under construction. It will be obvious to your Board that if the Port of Southampton is to derive full benefit from the advent of these steamers, it must be safeguarded against any possibility of reproach, or reflection upon its facilities, such as would arise were detention to be caused to the vessels in consequence of any deficiency in the draft of water in the channels to the port and docks.

We therefore deem it our duty to inform you that the builders estimate that these two vessels, when ready for sea in the Southampton service, will draw approximately 35 feet of water, and it is to be expected that on their arrival at this port from New York their draft will be in the neighborhood of 32 feet 6 inches (less coal, fewer passengers by the end of the trip). The steamers may be expected to take up their places in the service in the spring of 1912 and we confidently hope to receive an assurance from your Board that whatever dredging may be necessary to enable them to sail promptly, and to land their passengers without detention will be undertaken and completed before they are delivered.

The letter does sound a little threatening, and it is clear that White Star didn’t want to foot the bill for any structural improvements that were going to be of some importance. But although Southampton wanted the money White Star would bring in, they were wary about the degree of investment they were expected to make. In February 1909 the Harbour Board’s commissioner, A. J. Day, commented, with a good deal of caution and foot-dragging: “It does not seem necessary at the present time to do more than acknowledge this letter and state when the proper time arrives it will receive the serious consideration of the committee . . . As Mr. Curry states in his letter that these new steamers . . . will not be coming to Southampton before the spring of 1912, there can be no great urgency in dealing with this most important question of further dredging.”

Sanderson, on behalf of White Star, naturally retaliated by pointing out, not unreasonably, that the outlay on the work would be more than repaid by the income it would generate.

Nothing happened for almost a year, but in January 1910 a White Star deputation of big guns confronted the Harbour Board. It was led by Harold Sanderson, White Star’s general manager and a close friend of Bruce Ismay. Backing him up were Philip Curry, White Star’s marine superintendent in Southampton, Benjamin Steele, Herbert Haddock, and Southampton’s chief pilot, George Bowyer. The Harbour Board Committee pointed out that it hesitated “to incur such a heavy expense—some £100,000—for the benefit of two vessels which may or may not require more water than the 32 feet we have now . . . without securing a return to pay the interest to the stockholders and provide for the sinking fund.” Sanderson, on behalf of White Star, naturally retaliated by pointing out, not unreasonably, that the outlay on the work would be more than repaid by the income it would generate: “These large ships pay large sums of money in wages and it is not very hard to my mind to see that Southampton derives some benefit in the large sums of money directly or indirectly brought to the town by the crews and their dependents and the men who work the ships in port. I do not think it is fair that we should be looked harshly at for being the first people to bring large ships to Southampton. We were not the first to produce large ships, and we shall be followed in a short time by others.”

Nevertheless, the row continued until finally LSWR came up with the cash, though the Harbour Board’s committee was replaced with a less conservative group of people. In fact, further dredging proved necessary following Titanic’s near collision with the City of New York, a much smaller vessel whose moorings were broken by the suction power of Titanic’s massive hull as she was maneuvered out of port for the short crossing to Cherbourg on the first leg of her maiden voyage.

White Star and Harland & Wolff had no such problems with the Belfast Harbour Commissioners. Neither did they with those of New York, where, so great was John Pierpont Morgan’s influence, the White Star quays were extended (at taxpayers’ expense) by 100 feet to accommodate the new giant liners. In Belfast, as the Belfast News Letter reported on October 21, 1910, work commenced on a new graving or dry dock in 1903, which was completed in time for Olympic’s occupancy in 1911: “Belfast now has the honor of having built the largest ship ever launched [Oceanic, 1899], and it will soon have the distinction of being in possession of the biggest graving dock ever constructed. The work in connection with this necessary adjunct to modern and successful shipbuilding enterprise is now in its final stages, and it is expected that the dock will be ready for the admission of vessels in December, or in January at the very latest, but the formal opening will not take place until the summer.” Named the Thompson Graving Dock, in honor of the chairman of the Harbour Commissioners of the day, it was 850 feet long—extendable by a further 37½ feet—and carried 332 cast-iron keel-blocks to bear the weight of the huge ships it was designed to accommodate. It cost something approaching £350,000—a huge sum a century ago.

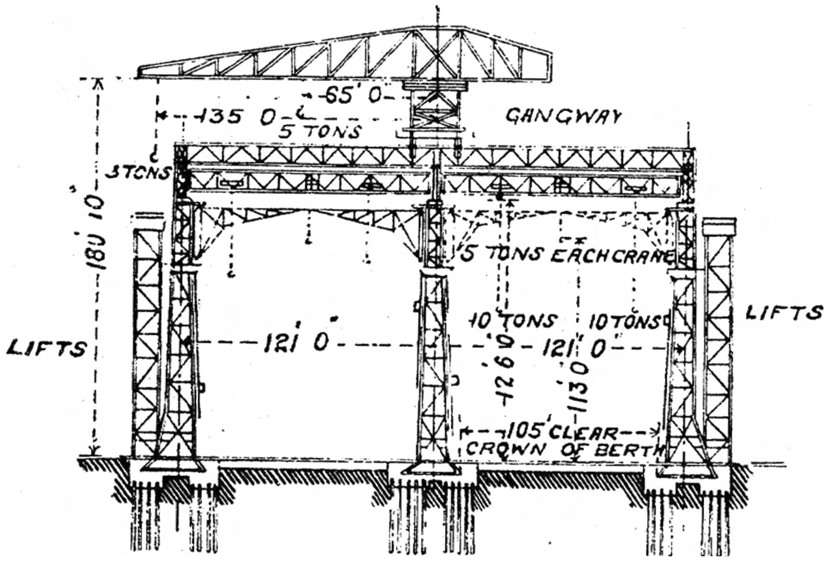

Section through the Arrol gantry over Slips 2 and 3 where Olympic and Titanic were both built.

In the meantime, the new Slips 2 and 3 were crowned with an enormous gantry, constructed by the Scottish engineering firm of Sir William Arrol & Company, responsible among other things for the Forth Bridge.

The gantry covered a massive area—840 by 270 feet, and 228 feet high at its tallest point. It was made up of three rows of eleven towers, each row 121 feet from the next, and each tower weighing more than 6,000 tons. It accommodated a number of cranes, but in addition, in order to lift heavy machinery such as the engines, a 200-ton floating crane made by Benrather Engineering of Düsseldorf, Germany, at a cost of £30,000, was installed at the fitting-out berth for the new liners. It stood 150 feet high and its two hooks could lift up to 200 tons between them.

With these enormously significant improvements, Belfast’s position as the world’s leading shipyard was confirmed, and the city basked in a sense of civic pride and international importance. The Belfast News Letter reported in glowing terms on October 21, 1910: “It is a matter of real gratification to all of us in Belfast that the Olympic and the Titanic should be built here, and in undertaking the construction of vessels of such enormous proportions, it is felt that Messrs. Harland & Wolff are maintaining their own splendid traditions and at the same time indicating the right of the Ulster capital to be reckoned as one of the great shipbuilding centers in the world.”

Construction work on the massive Arrol gantry in 1908. It cost £100,000 to build and carried the cranes and elevators necessary for the building of the Olympic-class liners.