ON Railroad Avenue, a short avenue two blocks from the mill, there was about a block of stores that were empty. Tom Moore and John rented an old wooden one-story structure for the union office and two doors away the bottom floor of a two-story brick building for a place from which to give out food and other relief.

“Now,” Tom Moore said when that was accomplished, “we must send a telegram—for help.”

“They will send help from up there?”

“As much as they can. And some people will come down. We’ve got to work hard. In a week everybody here will have used up all the fatback and flour they have on hand.”

Bonnie, Ora, Sally and some of the other women helped with the stores. Once Ora missed Bonnie, and found her out at the back of the store sitting on a keg. She was leaning over writing laboriously on an old brown paper bag she had found in the store.

“Why, I thought you had left us,” Ora exclaimed.

“No,” Bonnie said. “I was just writing something.”

“What is it?” Ora bent over Bonnie’s shoulder.

“You see, Ora, I was thinking about us, and I thought of a ballad we could sing. I thought of some words.”

“Read hit to me.”

“It’s not very fine. I just thought of some words, and wrote them down.”

“You read hit.”

“I could sing better.”

“Then sing.”

“It’s a mill mother’s ballad,” Bonnie explained. “I thought about us leaving our young ones . . .”

“You let me hear it,” Ora said, knowing that Bonnie was trying to put her off.

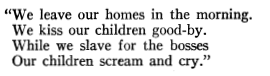

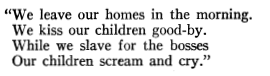

So Bonnie sang, faltering at first, from the paper, on which words were scratched out and written over—until she had found the words she needed.

“It’s all I’ve got so far,” she said.

“It’s real nice,” Ora told her, really admiring. “I’m a-going t’ tell Tom Moore and John so you can sing for all of us.”

“Oh no. It’s not good enough.”

Bonnie slipped from the keg, and was going inside again to help, but Ora pressed her down again with one hand on her shoulder.

“You sit right there and finish, Bonnie. We’ve got enough t’ help inside. You write that ballad. We’ve got t’ reach people’s hearts as well as their stomachs.”

From the relief store that evening they went to the meeting behind Mrs. Sevier’s boarding house. Bonnie had brought her covers over and her young ones were sleeping on the floor at Ora’s, so she could leave them at night. The meeting was in a field, and soon after the time set the place was almost full. After the speaking the people did not leave at once and Bonnie moved among them. Lillie Martin who was married and was now Lillie Thatcher was there with her husband’s father, old Ed Thatcher.

Lillie had married Tom Thatcher, one of the wild young men of the village. And it was a queer thing, but one that sometimes happened: after her marriage Lillie had settled down, but Tom kept up the sort of life he had led when he and Lillie ran around to the horror of all good churchgoing people.

“Where’s Tom?” Bonnie asked her.

“In the mill,” Lillie turned away, so that she might not have to answer again.

“We’ll make him come out in the morning,” Ed told her.

The people assembled had voted to picket the mills in the morning. This is what Tom Moore told them: “There are people like those who called a strike in Sandersville some years ago. These people would say to you, ‘Now you go home and stay there and we’ll talk with the owners and arrange everything for you.’ Then they will go to the owners and say, ‘You and me must come to an understanding.’ And they will bargain over you like people bargain over the counter for a piece of goods. And you are the goods. They call it collective bargaining. And it is collective bargaining. For those strike leaders collect our dues, and the owners of the mills collect our blood and bone, and our children’s lives.

“You all know how in the frame rooms the rove is drawn and twisted to make it stronger. First, six strands are put together to make a stronger thread. Well, we’ve got to stick together just like that rove. We’ve got to show fight. We’ve got to picket the mill and get all those still in there working for the owners to come out with us. And when we’ve shown that we can all stick together, then we will elect a committee from among us to talk with the owners. And the committee will come back and report, so we can vote on what we want to do. No one will decide what is best for us but ourselves.”

It was this talk which had made Ed Thatcher say what he did. Many people felt after Tom Moore and the other speakers had finished that they could clean out the mill next morning.

Bonnie saw young Henry Sanders standing near the box from which the speakers had said their words. His mother, bent and scrawny, old in work, was at one side. Around her, varying in age, but not much in size, were the eight young children that her dead husband had left her. Henry was the oldest, and he was sixteen, with the burden of them all on him, for his mother was a sick woman. He had worked in the mill since he was ten and had to put newspapers in the heels of his shoes to make him taller. Now, at sixteen, nearing seventeen, he had grown no larger than he was at ten or eleven. But he did the work of a man.

“How are you?” Bonnie said to Henry’s mother. She felt a loving care toward all the people, and a gratefulness to them for having come out, for seeing that this was the best thing to do.

Henry came up to them. “Hit looks as if there’s going t’ be a strike,” he said, when Mrs. Sanders had answered Bonnie’s question.

“I’m s’ glad t’ see you out,” Bonnie said to him.

“Well,” Henry told her. “I figured we was starving anyway, and might as well starve on our feet putting up a good fight.”

“Hit’s right,” Bonnie turned to Mrs. Sanders, “I didn’t have enough t’ feed my young ones, let alone cover their backs.”

Henry touched her arm. “Somebody’s a-calling ye.”

“Where?”

Then Bonnie heard Ora’s voice. “Bonnie, Bonnie Calhoun,” and Ora came pressing through the crowd. Behind her was Tom Moore.

“They want ye t’ get up on the box and sing your ballad,” Ora said.

A chill went through Bonnie. She had written the ballad because it had come to her, but she had not thought of getting up before neighbors and friends to sing. Her singing had all been done with other people.

“No,” she drew back from Ora’s hand that was pushing her toward the platform. “I can’t, Ora.” She was very frightened. Later she became accustomed to the singing. But for the first few times she dreaded getting up before the people as she did now.

Tom Moore said, “People don’t seem to want to go home. We’d like for them to hear something, and have had enough speeches. If you’ll sing it will help.”

“Well, I can try.”

They helped her on the stand. People turned to look and she felt their eyes on her. The faces were expecting something which she must give them.

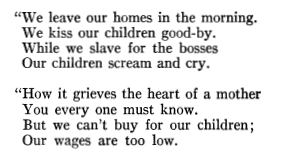

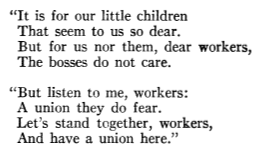

“Friends,” she said, “I am the mother of five children. One of them died because I had t’ work in the mill and leave the baby only with my oldest child who was five and didn’t know how to tend it very well. And with four left I have found it hard t’ raise them on the pay I get. I couldn’t do for my children any more than you women on the money we get. That’s why I have come out for the union, and why we’ve all got t’ stand for it. And it’s why I have made up a ballad about a mill mother. So they have told me t’ sing it for ye. And so I will.”

She stood with her hands straight at her sides and sang in a high clear voice that reached to the edge of the crowd.

There was a silence when she had finished. She stood, rather uncertain what to do next, on the stand. Then someone in the middle of the crowd called out, “Sing it again.” Others took up the words and from all sides came the demand, “Sing it again.”

“Now I will,” Bonnie agreed, “if you’ll all join in when you can. You all know the tune, for hit’s ‘Little Mary Fagan,’ so just listen to the words.”

Some joined in. Then it had to be sung again, and before long many were singing together the Mill Mother’s Ballad. When it began to grow dark the meeting broke up, and they went home to sleep or talk in preparation for the picket line next morning.

It was dark when they went home. And it was dark next morning when they gathered in the road outside the wooden store that had been rented for the union office.

Tom Moore met John at the door of the office. The light from the electric bulb in the store shone full on John.

“What’s that in your hand, John?” Tom Moore asked.

“Why,” John answered, “you can see. Hit’s my gun.”

“I thought,” Tom Moore said straight out, “John Stevens had made you understand better than that.”

“Hit’s a fight,” John insisted. “And this is the way I know how to fight.”

“Are all the men armed?”

“Most.”

“Come here,” Tom Moore pulled him into a corner of the store, for other people had come in.

Presently John laid his gun on the counter and remained beside it, while Tom Moore went out to the others who were standing in the darkness up and down the street.

“Bring me a chair,” he said to one of the boys.

He stood on the chair with the outside wall of the store behind him and spoke to the faces that he could not see.

“Some of our friends here,” he called out and his voice sounded hollow in the early morning air. It seemed to be going nowhere, for there was no light yet. “They have taken down their shot guns or their pistols, and have said, ‘Now I am ready to fight.’ I want to say to you, we can’t fight in that way now. We must use peaceful means to gain what we want. It isn’t that I want to keep you from fighting in the way you are used. But I know from experience we must fight with numbers. We must overcome with numbers and with spirit and determination. John McClure came this morning with his shot gun. Now he understands that it is best for him to leave it here. He is in there standing by the counter. And I want to ask all you men to go there and leave your weapons with him.”

Someone called out, “What about the Law? They’re armed.”

“They are, because they’re afraid of us. They have got as many weapons as a porcupine has quills, and if they should drive us back, which they won’t, they would speak of that as if it was a fine thing that they had subdued unarmed people. But we must go unarmed—first because we want the women and children along to help picket and don’t wish for them to get hurt, and second because it’s the best thing to do—and I’ll have to ask you to take my word for that.

“I hope all those with weapons will go into the store. John McClure will care for them all, and give them back when you come from the mill.”

He waited. One man stepped from the dark shadows of the crowd and went into the store. Others followed. They filed into the store and laid their weapons sorrowfully on the counter before John. He stood before them without a word. His head was bowed over, and he kept his eyes on the pile of guns and pistols and knives that were being heaped on the counter. When all had come he hid the weapons under the counter and left one of the boys on guard, for he had to help with the picket line.

As they neared the factory, marching two and two, John saw that the lights were on as if a whole force of workers was expected. Light had come, though it was only a pale glow from the east, and he could make out the forms of the deputies moving outside the wire fencing of the mill. He was watching them and did not see what was just before him. Something came across his belly and almost knocked the breath out, for he was walking fast. Frank said, “They’ve got a rope across the street.” And it was so. A thick rope, doubled, was strung from one side of the street to the other.

The line behind them came pressing on and spread out over the whole street against the rope. Ora was at the end.

“We’ve got t’ break it,” she called out, and pushed against the rope, until she stood out from the rest pushing. They were soon with her, until they made a semi-circle in the road pushing against the rope, but held back at the ends where it was fastened. The rope snapped at one end, suddenly, so that some at that end fell to the ground. They were soon on their feet, and formed in twos again, to keep up the march toward the mill.

At the mill gates the armed deputies with the butts of their guns forced the line into the road. They stood there, the people in the line, and called out to the deputies, most of whom were the higher-ups in the mill—people they knew very well.

Soon the workers began coming and they concentrated on these, for it was necessary to get all to leave the mill and stay together outside. The more who were out, the better chance there was to win.

Tom Thatcher came down the walk and Lillie stepped forward.

“Come with us, Tom,” she begged him. “Don’t go against your own.”

And Ed Thatcher who had lived in the mountains spoke to his son in a loud voice, “Be ye a coward, Son, that you can’t stand up for your own?”

But Tom went sullenly into the mill, guarded by two of the police with their guns, one on each side of him.

Lillie called after him. “Ye needn’t be so afraid, Tom. We ain’t a-going t’ hurt ye. We’re just sorry for ye.”

But there were many who turned right at the gate and joined the long line: and when they did, a shout went up, and they were welcomed by friends and acquaintances.

When the whistle for work blew the long line went back toward the office. There, with some words from John, they returned home. When the total was counted up they found that nearly all had come out. It was a great triumph. The Wentworth Mill was almost empty of workers. There were perhaps seventeen left in the mill.