Louis XVI’s wife, Marie-Antoinette, portrayed as a devoted mother in 1787, no doubt to combat the true stories about her over-spending, as well as the vicious slanders about her infidelities with both men and women. Her enemies had long since dubbed her ‘L’Autrichienne’ (The Austrian woman), a literally accurate description of her origins, but which also contained the word ‘chienne’ – French for ‘bitch’.

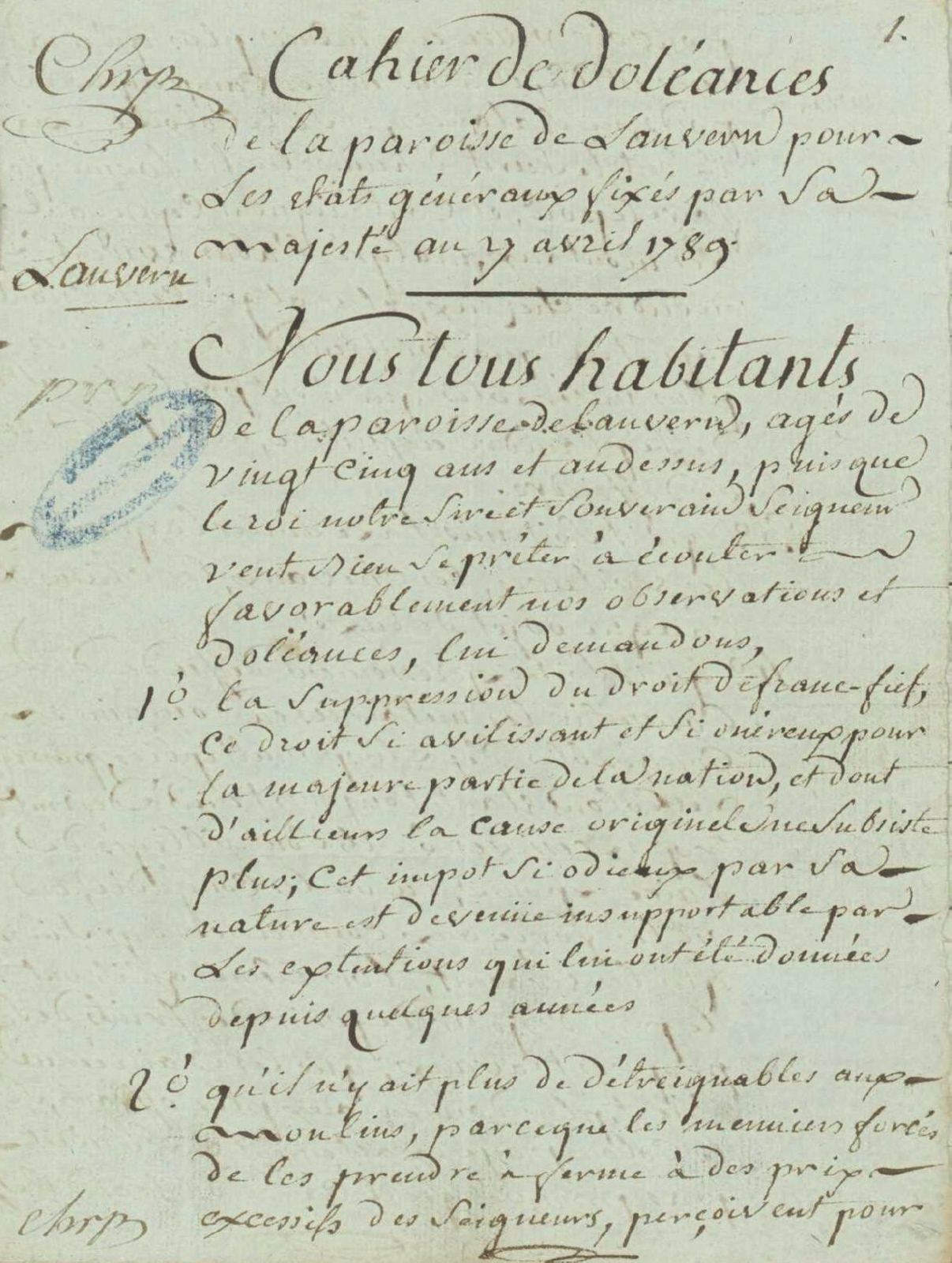

One of the 40,000 or so ‘cahiers de doléances’ (complaints books) commissioned by Louis XVI in 1789, allowing ordinary people to express their grievances. This one called for an end to aristocratic privilege, which it refers to as: ‘this tax so odious by nature, that causes so much hardship.’

The women’s march from Paris to Versailles on 5 October 1789. In fact, they were probably less heavily armed than this, and had to struggle through mud and torrential rain. Also, it is often forgotten that the Parisiennes originally went to Versailles to ask Louis XVI’s help in obtaining bread, not to demand his head.

The marquis de La Fayette, whose National Guard failed to keep the peace during the Revolution. He is often accused of fighting his own personal battle rather than supporting political change. Note the revolutionary rosette, the ‘cocarde’, on his hat, held almost out of view.

Paris, 14 July 1790, the celebration of the first anniversary of Bastille Day. King Louis XVI was the guest of honour at the ceremony, and received an oath of allegiance from politicians and the National Guard. France was still very much a functioning monarchy.

Louis XVI’s execution, on 21 January 1793 in the place de la Révolution (now place de la Concorde) in Paris. He was allowed to ride to the scaffold in a closed carriage, partly out of a fear that royalists might attempt a last-minute rescue.

In 1799, with the Revolution stalling, a young revolutionary general called Napoleon Bonaparte stepped into the power vacuum. Soon afterwards, France had an emperor who was just as absolutist as King Louis XVI or his predecessors had even been.