The polymer Glock magazine is metal-lined.

Like the Glock when it first came out, magazines for the Glock are unique. The magazines for the first model G-17s were very odd affairs to the American shooters who encountered them. Not only were they “plastic” but they were squishy, too.

The first Glock magazines were constructed by pressing a sheet metal shell into shape on three sides for the magazine tube. (Front and sides, no steel in the back.) The sheet metal channel was then held in place in the mould when the polymer was injected. The sheet metal acted as the inner walls of the magazine tube and provided shape and durability to the polymer tube.

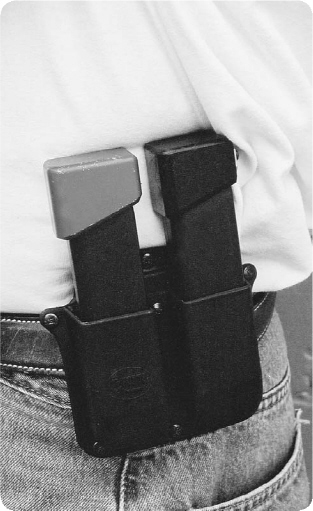

The design had many advantages. First, it was highly corrosion resistant. The only part that had any chance of rusting was the liner, and it wouldn’t rust easily. (The liners are nickeled spring steel and are meant to last a long time.) For its size, the Glock magazine had greater capacity than other magazines. The additional capacity was partly due to the Glock magazine being a fraction longer than other magazines of high-capacity 9mm pistols. Also, the shoulders where the double stack was funneled down to a single feed position are higher on the Glock tube. The third aspect that gave the Glock a few more rounds was that the tubes were a little larger in diameter. This was possible due to the polymer frame. (Some magazine pouches for 9mm high-capacity magazines won’t take Glock mags, due to the slightly larger diameter.)

Most pistols have a frame that encloses the magazine, which then has grips attached to it. The drawback to the frame-and-grips design is that everything you do constricts the design envelope left over for the magazine tube. For all of its wonderful feel and shape, and for being a huge advance at the time, the Browning Hi-Power only holds 13 rounds. (Interestingly, John Browning’s original design appears to be large enough to hold 17 rounds of 9mm ammunition. Wouldn’t that have turned heads in the late 1920’s?)

The polymer Glock magazine is metal-lined.

For an equally comfortable grip, the Glock G-17 holds 17 rounds. There is and was one drawback to the original design. The magazine would swell when stuffed full of 9mm ammo,and not fall out of the frame even when the magazine button was pressed. It was also a snug fit inserting it in the grip of the pistol when fully-loaded.

You see, in Europe, where the Glock was designed and intended as a military and police pistol, letting magazines fall to the ground is considered very bad form. In some circles it is even considered an abuse of issued equipment, and letting a partially-loaded magazine fall to the ground will get you a stern talking to. So, the first design of magazine would not fall out of the pistol. Well, sometimes it would, and sometimes it wouldn’t. Consider the “falling” status of your magazine as a contest between the magazine spring trying to push the magazine out,and the magazine tube swelling when loaded. When full, it wouldn’t fall out, too swollen. When empty, it wouldn’t fall out – the spring couldn’t push the lightweight empty tube hard enough to overcome the friction.

With just enough rounds to add weight, but not so many as to swell the tube, your old-style magazine will drop out when you press the magazine button. How many rounds? It’s a question you’ll have to answer for yourself. Some magazines drop with three or four rounds, others as many as six, some as few as two. And some will never drop.

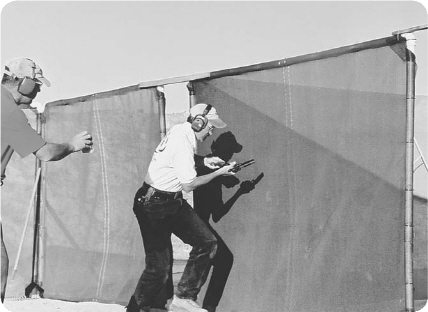

Practical competition shooters drop the magazines in the dirt, mud, sand, etc. We expect them to take it, and Glock magazines do.

“Drop free? We don’t make drop free.”

If you talk to a sufficiently indoctrinated Glock employee or rep, you will cause him just a bit of concern when using the term “drop free.” The factory designations are “Non Fully Metal Lined” and “Fully Metal Lined.” And there is only a passing thought paid to the various generations of designs, but there’s great concern that you might be installing a magazine baseplate to add capacity in places where it isn’t legal. The original intent was to keep the magazines in the gun, and the need to alter the design to accommodate the peculiar concerns of the American shooters came later. All other designs were made to improve the magazines for good, engineering reasons. That’s us: as good Americans we’re always causing trouble.

You’ll find Glock magazines of all vintages, but as far as the factory people are concerned, there are two: the originals, and those “American magazines.”

Yes, the hi-cap on the right is a no-name knockoff of the Glock, but the owner has tested it thoroughly and found that it works.

If you needed to reload while using one of those first magazines, you had to use your fingertips to pry it out of the gun. Remember, we’re talking of a design offered for the Austrian military trials, where the potential buyers are considering its issue to soldiers. A machinegun crewman is not going to be trained in speed reloads, and if after using his pistol for a few shots in an emergency he has to pry the magazine out to top it off, so what?

In the USA, that attitude didn’t go over very well. American shooters considered the magazine as almost a disposable part. When it was empty, especially for practical shooting competitors and law enforcement trainers, getting it out of the gun as fast as possible was the highest priority. Indeed, they were used to magazines that launched themselves out of the pistol when empty.

Where an Austrian soldier is issued one spare magazine and one in the gun for the pistol he is handed, and some European police departments issue only one magazine with a pistol, American shooters, competitors, and law enforcement officers viewed owning three or four magazines as an absolute minimum.

As an aside, when I first went through the Glock Armorer’s course, we were offered guns and magazines at very good prices. Hold onto your chair, because back in those days, we were offered the opportunity to buy high-capacity magazines for $10.50 each. That’s right, 10 dollars and 50 cents. The storage box for the original Glocks is a dead giveaway of the European attitude. One pistol, two magazines: one in the pistol and one beside the pistol.

The solution to the peculiar American insistence on drop-free magazines was simple: make the sheet metal pressing a four-sided, solid internal affair, and insert the new tube into the mould before encasing it in plastic. The exterior of the magazine was changed slightly so as to make it possible to determine which type a magazine was without having to insert it into a pistol. The giveaway is the notch in the upper rear where the slide passes through to feed a new round, right above the caliber designation. (Some very old magazines won’t be marked with the caliber at all, since when Glock only made 9mms they didn’t bother to so-mark the magazines.)

The first Glock magazines didn’t even have the caliber markings – just cartridge holes and the Glock logo.

Two drop-free mags flank a very early 9mm mag – so early it isn’t even marked “9mm” because that was all Glock made at the time.

So which Glock magazine do you have (in case it isn’t marked) and how can you tell if the feed lips are within specs? Measure the feed lip gap with a pair of dial calipers. If your magazines lips have spread (or been dented, bent or altered) you can tell quickly. Measure the width of the lips with a dial caliper.

The allowable dimensions are:

9mm: .325" to .335"

.40: .360" to .370"

10mm: .360" to .370"

.357: .360" to .370"

.45: .425" to .435"

If you have other magazines on hand, you’ll quickly find that Glock magazines hold their rounds tighter and in some cases the feed lips extend forward farther than other designs do. Nothing good or bad either way, just the way it has to be for a particular mechanism.

One peculiarity: A .40 magazine can hold 9mm ammo, and feed it into the pistol. As a stopgap measure to keep a 9mm running, I would put it up there with running your car with the tires flat. What it does mean is that if you get some 9mm ammo mixed in with your .40 ammo, it will feed and chamber. It may even fire. It won’t cycle the .40, and it won’t damage the pistol – just your reputation as the “high-speed, low-drag” shooter at your club. More than once I’ve watched a Glock-shooting competition shooter have the dreaded “Nines in a Forty” malfunction. The pistol is immediately reduced to a hand-operated single-shot pistol. And if the range officer or safety officer figures out what is going on quickly enough (as in before the shooter finishes the stage), the shooter’s score could suffer as well as his reputation.

One small detail long-time Glock owners have noticed, on their pistols and magazines, is the reluctance of Glock to give their competition any space. The pistols are not marked “.40 SW” but are only marked “.40.” Ditto the .357 SIG, which is simply marked “.357” for caliber. Publications under the control of Glock make no mention of other manufacturers, even obliquely in the caliber designation. I don’t blame them. I just find it curious. Is S&W going to die of envy because Glock won’t mark their pistols with “S&W” or “SW” even in the caliber designation?

Nothing new in it, though. Colt for a long time marked their revolvers “.38 Special” instead of “.38 S&W Special.” And even earlier than the .38 Special cartridge, they offered revolvers in “.38 Colt” and “.38 New Police” to avoid using the dread phrase “S&W” in the caliber marking or cartridge designation. Even today, the curious custom continues. Ruger refers to its .40 pistols as “40 Auto,” and so marks them on the chamber of each.

As with the other parts, there are upgrades to followers. The armorer at a GSSF match can upgrade your mags for you.

The old magazines that wouldn’t drop free have a rounded U-shaped notch. The drop-free magazines have a square U-shaped notch. Later iterations of the drop-free design have the sidewalls of the notch tipped outwards, so it is an angular slot. One other change made to the tube when going to the drop-free magazine was another American shooter-induced requirement. The top edge of the magazine shoulder was altered so it acted as a positive stop to magazine insertion.

Again, it is common in Europe to insert magazines with the slide forward. Or, if the slide is locked back, to carefully press the magazine in place. In the USA, we shoot until the slide locks back, drop the old and “slap” in a new one. (And sometimes slap it hard.) The old magazines could travel farther up into the frame than intended. The new shoulder prevented that problem. (If the magazine goes too high it wedges in place, sticks up too high, and the slide then can’t go forward.) The stop ledge also solved a minor problem again caused by the American insistence on slamming the magazines into place. The magazine riding too high could cause wear and damage to the retaining notch of the magazine tube, and the ejector and magazine feed lips. With enough wear the magazine might bind when inserted, or fail to stay locked in place when fired.

Two non-drops, a 10-shot, and a no-name copy of the Glock magazine.

One other change was to make the composition of the polymer of the magazine tube stiffer. The old magazines had a lot more flex to them, actually bulging when stuffed full of ammo. And in hot weather, partially-loaded old magazines could disassemble themselves when they were dropped. The stiffer polymer led to other problems, but we’ll get to that in a bit.

When the new magazines hit the market, everyone who could do it ditched their old magazines in favor of the new. When the Assault Weapons Ban law was enacted in 1994, a whole lot of non-drop free magazines came back onto the market, and you are as likely to find the magazine you are looking at to purchase is an old non-drop as a new drop-free mag. After the ban sunset, we saw a flood of new, non-drop magazines, such that the older ones are probably going to become curiosities. They still work just fine and can be had cheap in many instances. If you come across some in good shape don’t pass them up just because they don’t drop free. As practice magazines they work just fine.

In competition, having a mixture of the old and new can be a problem. If you don’t pay attention to the sequence in which you use your magazines, you may find yourself halfway between shooting boxes, trying to rip a non-drop magazine out of the gun against the clock. Also, since the old ones swell when loaded, you have to press them the entire length into the frame in order to seat them. A new-style Glock magazine is like any other pistol’s magazine in that once you give it a running start it will whack in place and lock up without you having to press it the whole distance. In daily carry, a non-drop magazine can spare you the embarrassment of having your magazine drop out at inopportune times. I’ve never had the exquisite embarrassment of having a loaded magazine clatter to the floor in a public place, but I’ve talked to those who have. It is something you should avoid, if at all possible. An original non-drop magazine isn’t going to fall out even if you remove your magazine catch entirely and do cartwheels down the hall. If you use a non-drop magazine as your carry magazine, just don’t be needing a speed reload when the shooting starts.

As good as they are, Glock magazines still need TLC.

There has to be at least one reader out there who is scratching his (or her) head. Why all the fuss and exhortation over magazines? Well, without trying to start an “old shooter vs. new shooter” schism, unless you were shooting actively in the early 1980s (or earlier) you just can’t realize what magazines used to be like. Early magazines were so bad they were considered almost disposable. Well, not all, but many.

For example, if you chose to shoot IPSC with a Browning Hi Power (the P-35) back in the “good old days,” you could count on good magazines. They were expensive, but good. Since the good ones came from Browning, you could count on them. Wartime surplus P-35 magazines were often quite good. Other pistols were not so lucky.

Ever wonder why the Luger, for all of its good feel and great looks, never caught on in practical pistol competition? The magazines. (Okay, so the wrong-way safety, pitiful sights and creepy trigger were problems too.) If you had a Luger with a magazine with matching numbers, you never let that magazine get away from that pistol. Other magazines, even those made before wartime production was hurried, couldn’t be counted on to work reliably.

Many other pistols had the same fault. Indeed, the entire reputation of pistols as being less reliable than revolvers is based on crappy magazines.

What of the legendary 1911? You could always tell a new practical shooter back in the early 1980’s; he was the one throwing his “gun show bargain” magazines into the weeds. The first article I was ever supposed to be paid for concerned itself with the detailed and continuing struggle of finding and keeping good magazines running properly. And one of the first bits of advice I offered was to not be cheap with magazines – go ahead and pay the $12 it took to get good ones. (What can I say, they were 1979 dollars.)

Increasing the capacity of compact models makes the magazines a lot longer.

The ages of Glocks mags so far are five. The first ones were 9mm only, didn’t drop free, and weren’t even marked as to their caliber. They also had a baseplate without an internal retaining plate. The baseplate was held on by the sidelugs only. The first magazines are 9mm only.

The second magazine was the transitional non-drop. It came into being with the introduction of the G-22. Transitional mags have the caliber marked and a retaining plate inside. The baseplate has a hole through it so you can poke the retaining plate out of the way on disassembly. The transitional magazines have three sides of metal on the interior and do not drop. The rarest of these are the .40 caliber ones.

The third age of magazines are the drop-free. They have square slots on the top rear. The baseplate and retainer look the same as the transitional ones do, but the part numbers are different. Don’t put Type 2 retainers and baseplates on a Type 3 magazine. The tolerance differences can lead to self disassembly.

The fourth magazine is the 10-shot. Ten-shot magazines are all drop-free. They use a different follower and magazine spring than their hi-cap brothers and sisters, but the retaining plate and baseplates are the same. The 10-shots were made during the Assault Weapons Ban and for a while were common as dirt. What with the expiration of that odious law everyone with any spare cash has gone out and bought hi-cap magazines.

The fifth magazine is a curiosity. It is a hi-cap made during the time of 1994 to 2004, marked “For Law Enforcement and Military Use Only.” It simply is a drop-free magazine with the warning machined into the mould. If you weren’t an LEO or military person, it was a crime to own one of these back then. It still is, in some jurisdictions.

The latest Glock magazines; the .45 GAP, are only of one kind: they are drop-free, tipped-out stripper slot, not marked LEO Only.

The two variants come in the drop-free and the 10-shot magazines. Some drop free mags have a square slot on the back. There are also drop-frees with what cowboys would call a “Lazy U” slot, where the sides are angled outwards. Why the change? No word from Glock, but one Glock representative I talked to said the change was made to indicate that the magazine incorporated a new design in the inner tube assembly.

Another change first appeared on the 10-shot mags and involves the side of the taper. To make fast reloading easier, part of the taper was cut away to a sharper angle.

Yes, you can obsess over magazines. You could even spend time collecting nothing but magazines. Keeping them running is pretty easy: strip ands scrub them now and then, don’t drop them too much, and don’t loan them out.

The only things most owners worry about are 1) will they work, and 2) did I get them all back when I’m done shooting?

On the right is an early 10-shot 9mm magazine. On the left is the upgraded tube shoulder design.

Some magazines could always be counted on. S&W magazines were always dependable, but the DA/SA trigger of the S&W line was viewed back then as a hindrance to “good shooting.” The trick was finding good magazines for a pistol that was suitable for competition or carry. The problem would quickly go away with the changes market forces brought about. Just as Glock was entering the market, the 1911 world was changed with the introduction of the Wilson-Rogers magazines. (Now sold in an improved version by Wilson as the 47D, and now replaced by the #500.)

Ruger entered the centerfire pistol field with their durable and reliable P-85 soon after the Glock appeared. In a few years the whole idea of cheap, crappy and unreliable magazines being the norm for pistols was overturned. The lousy ones still exist, but they aren’t what shooters expect to be their usual gun purchase fate. Lousy magazines are to be strenuously avoided, because good ones exist. Such an attitude and situation was not the case before the early 1980s.

Today, you can buy ultra reliable and durable magazines for less than what they cost back then. But in the early 1980s, the idea that a high capacity 9mm pistol could be had with magazines as tough as rocks was almost as radical as the idea of a pistol with a plastic frame.

I know of more than one Glock owner who has never has his magazines apart. Partly because they never fail (at least in 9mm) but also partly due to the sometimes difficult disassembly procedure. While stripping the pistol is a piece of cake, getting the magazines apart can sometimes be a real hassle. The nature of the polymer is the problem. Since it is a slightly flexible material, the interlocking parts of the magazine have to be relatively large and strong to take the load. The magazine is composed of five parts; the tube, follower, spring, retainer and baseplate. (Some very old magazines were made without the internal retaining plate.)

The arrangement is the same as any other pistol magazine, the follower rests on top of the spring, the retainer on the bottom. The baseplate slides on the lips on the bottom of the tube, and the retainer locks the baseplate. On the Glock there is an additional retaining design. The lips on the bottom of the tube have square shoulders, that catch in the baseplate. The retainer, inside the tube at the bottom, prevents the tube from squeezing inwards and releasing those shoulders from their notches. That’s your mission, should you choose to accept it, to get those shoulders out of the way.

The start is simple. Look at the bottom of the baseplate. Is there a hole? If so, you have a later magazine. If there is no hole, you have an early magazine. (Or, curse your luck, an early baseplate on a later magazine. Get ready for some struggling.) On the later magazines, take the unloaded magazine and insert your handy-dandy Glock disassembly tool into the hole in the bottom of the baseplate. Push upwards on the retainer until you have pushed it up and out of the way, and it has snapped to the side or front of the tube.

You want to make sure you have the correct baseplates on your magazines for proper function.

After you’ve pressed the internal plate out of the way (if it has one), squeeze the tube and slide the baseplate off.

Once you get it past the slide tabs, the baseplate moves easily.

Now squeeze the sides of the tube bottom while sliding the baseplate forward off the tube. The older, non-drop-free magazines were sometimes a struggle. The new ones, with their stiffer composition, can be even worse: a three-handed job. You have to squeeze strongly and flex the tube enough to clear the notches. I have seen some shooters who didn’t have enough hand strength to accomplish this resort to using pliers or even a vise. Careful! You can crush the tube (not easily, but you can) and then you’ll be in the position of explaining to the Glock warranty department just how it was you came to mangle a magazine. They might replace it. They might not. They aren’t in the business of replacing perfectly good magazines just because you got a little heavy-handed in disassembly.

The early magazines lacking the internal plate are simple: Squeeze the sides to release the tabs from the notches in the baseplate, and slide the baseplate off. The softer composition of the early magazines does make the task easier, but it is not always easy.

With the baseplate off, remove the spring and follower. Wipe the dust, crud, grit and powder residue off everything. Refrain from lubricating it. Oil will simply attract dirt and grit, and you’ll have to clean it sooner. If you want to use something to keep your magazine running smoothly, Mag Slick from Krunch Products is one option. As a synthetic and nontacky lubricant it will smooth the internal parts function without attracting grit.

The Pearce extension does not increase the capacity of this G-26 past the former legal limit. It does make it easier to shoot.

Reassembly is the infamous reverse order. Install the follower and spring, making sure you get them pointed in the right direction. Press the spring down, put the retainer in place (correct side: the little bump towards the baseplate) and start sliding the baseplate on. You’ll need both hands and some dexterity. The trick is sliding the baseplate on, and keeping the retainer pressed out of the way, while you squeeze the rails to clear the little shoulders on the rails for the baseplate to slide fully into place.

After a few times, you’ll either get the hang of it or you’ll wait until your magazine malfunctions to go through it all over again. It will be a long wait in 9mm. In the G-22 you may have a shorter wait, as I have heard their springs don’t last as long as they do in the 9mm magazines. My G-22 magazines and springs are 15 years old at this point, with a few tens of thousands of rounds through them, and are still working fine. But your mileage may vary.

Oh, and if you want to strip and clean your magazines, do them one by one. Don’t be in the position of having a jumble of tubes, springs, followers and baseplates on the table, and not remember which ones went together. It may not really matter, but it is asking for trouble to mix parts in magazines that were working before you started. As a friend of mine has been known to comment: It’s Murphy’s Law, not Murphy’s Suggestion.

In the world of firearms accessories, it isn’t unusual to find a bunch of manufacturers making parts, and parts only, for firearms they themselves don’t make. The biggest example is the 1911 pistol. There are a dozen people who make magazines for it, and most every manufacturer (three dozen or more) of the pistol offers its own magazine as well. (The pistol manufacturers’ magazines almost certainly comes from one of those dozen magazine makers, but since they buy hundreds at a time they can have their name put on them.)

You could buy a 1911, and then buy a lifetime supply of magazines for it, and not have two of any maker’s magazines.

Not so the Glock. The reason? Polymer. The other magazine makers are all set up to make magazines out of steel. Whether they fold and weld or extrude the tube, they all make them out of steel. If you’re set up to process sheet steel into magazines, making a new model for a different pistol is a matter of buying or making new pressing forms. If you want to make polymer magazines, you have to invest in a plastic injection moulding or casting machine (no small or cheap thing, by the way) and buy or make moulds for each magazine you plan to offer.

Why not make steel mags for Glocks? A steel magazine tube and the polymer magazine catch on a Glock don’t go together well. The weight of a loaded magazine, the spring pressure pushing down on it, and the recoil of shooting all act to tear up the polymer magazine catch in short order when using a steel magazine in a Glock. There are metal and metalized polymer magazine catches, but why install a different mag catch just to use a non-Glock magazine? Also, the steel magazines need a bit more care.

Serious shooters who use steel-tubed magazines, especially the high-capacity ones, fuss over their magazines. You see, steel bends. Bend it far enough, and it takes a set, and it does not spring back from the bend. A serious competitor will measure the width of the feed lips of his or her magazines and note the distance in their log book. Once a month, or just before a big match, they’ll measure the width again to make sure the lips haven’t been dented or spread from use. If need be, they’ll carefully adjust the feed lips.

All of that worry and fussing is wasted on Glock magazines. The lips don’t bend, as the polymer coating offers enough protection to keep them from getting whacked hard enough to bend them. The polymer also acts to support the steel liner against fatigue from constant use. The polymer may peel away from the steel, crack, break off, flake or otherwise become very ugly looking. As far as Glock is concerned, as long as it still feeds reliably (defined by Glock as 100 percent) and locks the slide back when empty, it is not in need of replacement.

The best magazines for your Glock are factory originals. I have never had much luck with the steel aftermarket mags, but I have had good luck with one brand of aftermarket polymer, called Scherer. They made good polymer mags for the Glock, and the ones I have work flawlessly.

You’ll run into a lot of magazines that will only hold 10 rounds, despite the tube and frame size potentially allowing more. For those of you who have already forgotten, there was a law passed back in 1994 that mandated ten round capacity. Called “the Crime Bill” or “Assault Weapon Ban” or simply “the Mag Ban,” the 1994 bill made the new manufacture of “high-capacity feeding devices” (government speak for magazine) against the law. New magazines up to 10 rounds could be made, and the old high-capacity mags could still be owned, bought sold and traded. But no new ones could be made except for law enforcement agencies and the military. And the magazines produced for them had to be specially-marked so there was no doubt as to what they were.

Passage of the law simply caused prices to skyrocket. For a while, original-capacity Glock magazines were being sold for over $150 each. Then a few things happened. One, common sense crept in. A hundred and fifty dollars is a lot of ten-shot mags and ammo for practice, and shooters stopped being so eager for hi-caps. Second, the firearms wholesalers started working with police departments to trade up. A wholesaler could offer to trade a bunch of .40 caliber Glocks to a police department in exchange for their 9mm ones and all their magazines. To sweeten the deal, the wholesaler might even throw in night sights or compact versions for full-size guns. Having traded gun for gun, the wholesaler would then sell the guns to retailers with one high-cap magazine each, and offer the extra magazines at a fair but profitable price. After all, his cost in the traded-tothe-police new magazines is less than $15 each, so he can afford to be generous and sell the old ones he gets for a mere $40 wholesale.

Do you really need high-cap magazines? Perhaps not, but since you can have them, why not?

So, for those looking for magazines on the used market, that explains why most of the hi-caps you saw from 1994 to 2004 were 9mm. For a while, there was a huge screaming match going on about pre-ban magazines. You see, the law merely stated that magazines produced before September 13, 1994, were legal, and those made after were not but it made no mention of made where. That’s right, the argument concerned overseas magazines.

By a strict reading of the law, every magazine on the planet manufactured before September of 1994 was a legal hi-cap magazine. Under the law, Glock could have traded those magazines from their current owners (with new, hicap ones for countries where there wasn’t a capacity ban) and then imported those magazines here, and thus had an immense stockpile of legal hi-caps. They could have owned the pistol market in those 10 years.

When those in the government who hadn’t previously figured it out found out, they kicked up a fuss and you’d have thought Glock and all the other importers were trying to import nuclear weapons or something. The end result was that the import paperwork never left the desk of whoever was supposed to approve the transfer. Well, it was a good try. Now it is all moot, as the law has expired.

With luck, we won’t have any more hi-cap bans and “LEO” markings such as this will simply be collectors’ curiosities.

Magazines weren’t the only article restricted by the Assault Weapons Ban of 1994. This isn’t even a select-fire rifle!

One wag has suggested that we not adopt the terminology of the enemy, and thus we shouldn’t be calling the 17-round G-17 magazines “high-capacity” magazines. They should be called “standard-capacity” magazines or “normal capacity and the 10-round ones should be “undercapacity” magazines. While I appreciate a good tongue-incheek joke, the government back then had defined them as “high-capacity” and any attempt at changing the terminology will probably get you branded as some sort of loony curmudgeon.

Some states still have a hi-cap bans on their books. The poor unfortunate souls who happen to reside in these places cannot get new hi-caps and cannot even buy old ones unless they had bought them before the state law was passed.

What to do now? Buy lots of hi-cap magazines, and get involved in politics to keep future bans from happening. Join groups, donate money, and send an occasional letter to your representative.

In the old days, you saw tubes offered in magazines and parts catalogs offered as replacement magazines. Somehow, a tiny spark of rational thought had crept into the bill that became the Assault Weapons Ban of 1994. While new magazines were banned, old ones were still legal to buy, sell and trade. And existing ones could be repaired or replaced. Those tubes you saw for sale were to repair or replace existing magazines. It was against the law to use them to build a new magazine. The supply of replacement tubes for Glock pistols had not been as great as that for other pistols due to design. If you make magazines for, say, a 1911, you make them by bending sheet metal. To make some other design you modify the tooling that bends the sheet steel and make the new design.

To make Glock magazines, you need the sheet metal bending equipment to make the liners, but you also need the injection moulding equipment to finish the job. A much bigger investment.

The current maker of replacement tubes is Scherer. I have had good luck with their magazines. They are lined polymer and they work. You can also buy complete magazines now that the hi-cap law has sunset. You probably should lay in a supply of spare parts, if for no other reason than that you might lose or break some while cleaning. And you never know, if some sort of law ever passes again, you may find those spare parts very useful.

If your magazines break or fail to work, you can send them back to Glock. However, be aware that they will not replace magazines that are out-of-spec due to normal wear-and-tear or that have obviously been abused. What you’re likely to get is one of three answers: 1) your magazines are used-up, it isn’t Glock’s fault, and you need to buy new ones; 2) your magazines work, and despite their shabby appearance they meet the Glock performance specs so you’ll have to pay for shipping them back; or 3) they are worn-out and cannot be repaired, and how many new ones do you wish to buy?

Do you need hi-caps?

Ah, that’s the question, isn’t it? Yes, for some applications you sure do. For self-defense, law enforcement, and military applications, having a hi-cap mag is very comforting. Were I to be in the position of going through doorways on a SWAT team for a living, or riding a helicopter on the payroll of the Army or Marine Corps, I’d sure feel a lot happier with more than 10 shots per in my magazines. (I’d also be comforted by the presence of lots of other firepower carried by those riding along with me.)

The question always comes up, “How much does an extension increase capacity?” In order to answer that question at least partly, I used two of my own magazines as test subjects. One is a 9mm for a G-17, the other a .40 for a G-22. The test was simple: load them to maximum capacity with each of the extensions installed, and see if I could seat the magazine.

Since each round decreases the available space in a magazine by a constant value, why would seating be a problem? It is possible, if the variables stack up just right, to get the last round into a magazine without any extra space to compress the stack under the slide. You see, the rounds have to rise up into the slide’s path. That means when the slide is fully forward it rests on top of and presses down the stack of rounds and magazine spring. If the stack doesn’t have any extra travel left, you can load the magazine with X number of rounds but can’t get it seated no matter how hard you try. In such a case, that particular magazine has a capacity of “X minus one” and you must take care when loading it. Otherwise you could load it up, forget about stripping off the top round, and find in the middle of a match that you can’t get that magazine seated no matter how hard you hit it.

The situation is one that many AR-15 shooters are familiar with. It is possible to stuff magazines with one too many rounds. Some 20-round magazines will “hold” 21 rounds, and 30s will “hold” 31. I use quotation marks because while you can get 31 rounds in (as an example) and even get the magazine to seat (only with the bolt locked open), firing the first round will create a malfunction as the friction is too great for the bolt to overcome.

So I loaded the two magazines with each extension to as many as it would hold, then seated and fired the first round. I then pulled out the magazine and stuffed it full again. And then fired one round, repeating until I had fired each magazine 10 times fully-loaded. Why do all this to just one magazine of each? Magazines can vary in their capacity. I know, I know, they are industrial products created to be as identical to each other as possible. In the single-stack world, it isn’t a problem. If you buy a truckload of Chip McCormick eight-round 1911 magazines ( just as an example) you will die of boredom loading each to check capacity. They will all hold eight. No more, no less.

However, in hi-cap magazines, things are different. Otherwise identical tubes can hold a round more or less than other tubes. (Smaller rounds, especially the nines, and the rounds are double-stacked) If I used one extension on one tube and another extension on a different tube and came up with different capacities, I’d have to swap and try again. Better to simply do the check to one particular magazine in each capacity and see what happens.

The resulting capacities are as follows:

|

9mm |

.40 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Taylor Freelance +4 |

23 |

20 |

|

Arredondo |

23 |

20 |

|

Grams |

23 |

19 |

|

Dawson |

22 |

20 |

However, there has been a counter-current in regard to demand. In the 1990s, a large number of states changed their CCW laws to Shall-Issue from May (or Never) Issue. Carrying a full-sized gun concealed isn’t easy. It is harder still if you are average or smaller in size. I’m 6'4" and 205 pounds, and I used to carry a full-sized 1911 all day. At the first opportunity I switched to a Light Weight Commander. When I got my hands on my first compact Glock, it was smaller and lighter still. Many other shooters who have CCWs have figured the same thing out. If you’re going to carry a compact pistol, you aren’t going to get 17 shots anyway. Since you can reload quickly, 10 is probably enough.

As an unintended consequence of the switch from 1994 to 2004 to 10-shot mags and compact carry guns, interest in the big calibers is greater than ever. After all, if you’re going to be carrying only 10 shots, they might as well be the biggest 10 you can wrestle into the gun. Ten shots of .40 or .45 are a lot more comforting than 10 shots of 9mm. With the new magazines, the calculation gets a lot more interesting. Eight or 10 .45 bullets, vs. 15 9mm? And if those 9mms are +P or +P+?

All manufacturers had to comply with the 1994 AWB, not just Glock.

Scherer makes replacement tubes and assembled magazines. They’re good, although snobs might prefer Glock-made mags.

In many competitions, you don’t need more than 10, then or now. In GSSF competition and in USPSA Limited-10 or Production Division, or IDPA matches you can’t have more than 10 rounds in a magazine. In The Steel Challenge, if you need more than 10 you’re losing in your class. (Some might argue if you need more than five you’re losing, but we won’t go there.)

But in some competitions, more than 10 is not just nice but a must. If you’re shooting bowling pins and are in the 9-pin category, 10-shot mags are a definite handicap. Shooting Open or Limited in a USPSA match with 10-shot magazines is a sure way to end up losing. And limiting yourself to 10 shots at the American Handgunner Shoot-Offs is s sure way to lose crucial bouts in Open or Stock Auto. We now have the option, which we didn’t for 10 years.

As I mentioned before, using a non-drop original magazine as a carry magazine makes sense if you’re worried about dropping your magazine inadvertently. If all you have are drop-free magazines, a bit of paper tape can keep the magazine in and still allow you to do a reload. Yes, I’ve heard people argue that 17 is enough, and expecting to still be in the fight and reloading after emptying one magazine is beyond optimistic.

My view on reloads is that I’m not as worried about running out as I am about other problems. If you have only one magazine, and anything, anything at all happens to that mag, you’re done for. Falling, having the gun or holster struck, whacking the baseplate on a door frame during the start of your fracas – oh, many things can render the magazine in your pistol inoperative. A spare magazine makes sense. If anything, the spare should be bigger than the one in the gun, not the same size or smaller. Packing and keeping concealed a magazine is a lot easier than concealing a pistol.

You can use hi-caps in smaller guns. This G-27 with a G-22 mag and Grams extension holds 20 rounds of .40 ammo.

The Pearce extension on a G-36 bumps capacity from six to seven shots of .45 ACP and gives your (or at least my) little finger a place to rest.

Even in the polymer world of Glocks, there is a perceived need for metal. One way to get empty or partially-empty magazines to eject cleanly is to increase their weight. Brass magazine pads do that quite nicely. The CPMi Glock brass baseplate for a G-20/21 weighs 1220 grains (about .174 lb.) and adds a significant amount of weight to a magazine. For someone who wants durability without too much extra weight, CPMi’s aluminum baseplates will keep your magazine togethe, and add only a fraction of an ounce to the total empty weight of 2.75 ounces for a G-17 magazine.

The only drawback to getting aftermarket baseplates, whether they increase capacity or not, is magazine age. You have to know what version magazine you have in order for the maker to get you just the right baseplate. (It goes without saying you’re going to tell him model and caliber.)

This G-30 .45 magazine already holds 10 rounds.

For USPSA/IPSC Production Division competition, this G-19 and its 10-shot magazines are very competitive. And they make a great carry package, too.

On the other hand, if you want a larger pad for more-certain insertion but don’t want to increase capacity and aren’t too keen on adding metal to your polymer pistol, then Arredondo has the answer for you. (They have the answer even if you don’t have an aversion to using metal accessories.) The Arredondo standard basepad fits both 10-shot and high cap magazines and doesn’t add any capacity while doing so. The basepad is in two parts and uses the standard spring and follower. Disassemble your Glock magazine and set aside the factory baseplate and locking plate. Slide the upper half of the Arredondo pad over the top of the mag and press it down to the bottom. Press the bottom half over the magazine spring and hook the fronts of the two halves together. Now compress the rear ends toward each other. You may find using the included disassembly tool is an aid to getting the tab on the assembly compressed so the two halves can click together.

Once clicked, they will stay together until you use the disassembly tool. To take them apart, use the tool to compress the rear tab and unlock the halves. Pivot the halves apart, and slide the upper off the tube.

There are a few ways to increase capacity. One is to go out and buy higher-capacity magazines. The other is to increase the capacity of the magazine you have.

The CPMI extensions can add a round or two, or not, depending on which one you get. They are frame-specific, so get the ones that will fit your Glock.

Before we go any further, I would be remiss if I didn’t tell you the following: DO NOT put any of the capacity-increasing gizmos we will be discussing onto a post-ban 10-shot magazine if you live in some place like California or New Jersey. Even if it works, it is a violation of state law, a felony, and subject to stiff fines and severe prison sentences. Back during the federal ban I almost bolted for the door the first time someone showed me how they had wrestled a +2 basepad onto a 10-shot magazine. Doing so in some states now is the same thing, differing only in the uniforms of the guys busting down your door.

The first of the capacityincreasing accessories were the Glock +2 baseplates. A pyramid-shaped hollow baseplate, the +2s simply replaced the existing flat baseplate and added two more shots to a magazine’s capacity. (That is, two more 9mms and one more .40. They were never made for 10mm or .45.) They fell out of favor for a few reasons. One, they only added two shots. Two, they came off. If shooters were going to fuss over a new baseplate and add more shots, they wanted more than just one or two; they wanted as many more as possible. Now, if what you want is only an extra round or two, with minimum extra bulk, then the CPMi hollow Glock pads work for you. They add a round or two while adding less than half an inch to the overall length of your magazine. And they won’t come off accidentally.

Manufacturers of competition replacement baseplates made them as long as the rules (if any) for those competitions allowed. Thus, capacity jumped up to +4, +6 and +8. Also, as I mentioned, the original +2 baseplates suffered an embarrassing problem: they came off. With the weight of the ammo, and the tension of the spring, the baseplate was under a lot of stress. The pyramid shape allowed for more leverage if something whacked the Glock +2. It isn’t at all uncommon for police officers to whack their holstered gun against door frames, car doors and frames, vending machines and the like. The +2’s had a tendency to pop off and spew the spring, follower and ammunition all over the floor or ground.

Clockwise from upper left: a Dawson; an Arredondo; an Arredondo 10-shot-only; a Grams; and a Taylor Freelance.

I’m not picking on police officers when I bring things like this up. They were the first ones to go into Glocks big, and you learn a whole lot of interesting things when you issue a thousand of anything to people who wear them all day and keep records.

If you have a +2 extension that has never come off of one of your magazines, great. Don’t swap it to another tube. I’ve seen competitors at matches with duct tape applied to keep their +2s on. (Yes, it is an ugly sight. No, I don’t know why they insist on using gray duct tape instead of using something more suitable like black.)

The higher-capacity baseplates like the Taylor Freelance, Arredondo, Grams and Dawson use a more secure method of attachment than the factory +2 arrangement and are not prone to sudden disassembly. The first three feature plastic machinings or castings, while the Dawson is machined out of aluminum and anodized in an array of colors.

The Taylor +4 and +8 extensions (actually +5 and +9 9mm rounds) use an aluminum plate they call the Fort Knox retainer, one that is bolted onto the back of the extension with a pair of cap screws. You couldn’t knock it off with a ball peen hammer. Machined from blocks of delrin, they add very little to a mag’s weight.

The Taylor Freelance isn’t caliber-specific, as it uses the factory follower. But you will have to specify if you are using a 9mm/.40 tube or a 10mm/.45 tube. Also, tell them if it is an original or drop-free tube.

To install a Taylor Freelance, disassemble your magazine and set aside the baseplate, inner place and spring. Place the follower on the new spring, and insert into the magazine tube. Unscrew the locking screws from the Freelance extension and set the screws and retainer aside for the moment. Slide the bottom of the spring into the Freelance extension. Line the spring up so one of the forward coils is at the front of the tube, and wriggle the extension onto the mag tube rails. Once it is in place, screw the Fort Knox locking plate down. Disassembly is the traditional “reverse order.”

The Arredondo extension uses an upper moulded collar and a clip-on bottom and comes with a new spring and a disassembly tool. As it does not replace the follower, you need only specify if it is a 9mm/.40 tube or a 10mm/.45, and whether or not it is a drop-free.

To install, disassemble your magazine and set aside the baseplate, inner place and spring. Place the Glock follower onto the Arredondo spring provided in the kit. Slide the upper collar over the magazine. It will stop on the bottom lip of the magazine tube. Insert the follower and spring. Then press the Arredondo baseplate onto the extension, compressing the spring between them. Once both sideclips have locked into place, you’re done.

The Taylor Freelance Fort Knox retainer. This puppy isn’t coming off accidentally.

To disassemble, use the provided tool to simultaneously press and unlock the sideclips. (Unload the magazine first, and keep your hand over the baseplate, as the spring will try to shoot it off the end of the tube.)

The Grams uses a pair of interlocking delrin parts that are held together by a steel “U” clip that passes through them. Disassemble your magazine. Replace the old spring with the new, longer spring and Grams follower. The Grams magazine extensions are caliber-specific, so you’ll have to order the ones you need. You won’t be able to swap them back and forth between 9mm and .40 unless you’re willing to use the factory follower.

Slide the upper assembly down over the mag tube until it rests against the bottom lips. Use the Grams baseplate to compress the spring, and once nestled together, press the stainless U clip through to secure the assembly. Again, it’s a bank-vault solid assembly that won’t come apart when you drop it. To disassemble, pry the U clip out of the closed position, and pull it free of the assembly. Once free, the baseplate will try to shoot off, so restrain it.

The Dawson lives up to its nickname, “Team Awesome.” It is a beautifully machined piece of aluminum with a sliding door as the retaining latch. Dawson machines a dovetail on the side of the baseplate and then machines and fits a door/latch that rides on the dovetail. The best part (besides the anodized colors)? The door has a retaining pin so it doesn’t come off the baseplate.

To install, strip your magazine and place the factory follower on the Dawson replacement spring. Insert follower and spring into the magazine and compress it with the Dawson baseplate. Tilt the baseplate to catch it on the rightside tube rail, then tilt it back until it is flush with the bottom of the tube. Slide the door shut. The Dawson is so trick and cool that I know competitive shooters who switched all their magazines over to Dawsons just for the look. It didn’t hurt that they are hell for tough and guaranteed.

For competition, any of these is a hot ticket. The +4 is still short enough to stay under the Limited equipment rules of USPSA, and the +8 stays within the Open length restrictions. A G-17 with scope and compensator, fed a magazines with a +8 on it, can be stoked with 27 rounds of 9x21 ammo, keeping up with the 1911 hi-cap frames (17, plus nine, plus the one chambered.)

Beven Grams in particular extolls his extension as being “impact resistant.” Thinking about it, I recall that every range I’ve been to West of the Rockies (Beven Grams is based in California) has range bays composed of river rock and parking lot gravel. (Here in Michigan we have sand. Sand, sand, and clay. In the rain they turn to mud.) I’m assured by the shooters in the Pacific Northwest that they have lots of slick mud. (In the rain, they use straw to cover the paths, leading their ranges to end up being composed of paths of stucco until the straw wears out or sinks out of sight. “Paths of Stucco.” Sounds like the title of a romance novel.)

The Arredondo extension is easy to assemble, requires their tool to disassemble, and works like a champ. Tough,too.

While thinking this over, I could feel a test protocol forming in the back of my mind. Back when I was getting my degree, we used to play a game between classes called “Stopper Hockey.” Back then, chemistry students had to form their own glass for reactant vessels, and many vessel designs required rubber stoppers. The bigger ones were the size of a hockey puck, so we’d kick them down the aisles between the chem benches. I decided to play a little “magazine hockey” as well as some other cruel abuses of fine pistol magazines.

I first borrowed seven magazines from a local law enforcement officer (he too wanted to know The Truth) and we met at the range. I borrowed from him four 9mm and three .40s, all fullsize, hi-cap, LEO-Restricted magazines. (The test was first done during the Assault Weapons Ban.) We figured if we trashed the magazines he could always turn them back in to the departmental armorer for new ones. And the knowledge would be worth it. I also installed the Arredondo no-cap extension on one of my 10-shot Glock magazines.

What I didn’t do was conduct the tests with a +2 baseplate. I already knew what the outcome would be and didn’t feel like chasing magazine components around the range.

I installed one of each of the three (Taylor Freelance, Arredondo and Grams) hi-cap extensions on the 9mms and one each on the .40s. The Dawson I installed on a 9mm tube. The installation went smoothly, and there were no problems in the few minutes it took to rebuild the eight magazines.

The Grams extension is machined delrin, tougher than a two-dollar steak, and easy to take apart and clean (if you ever need to).

Before I describe the tests, let me tell you that I almost chickened out when it came to the Dawson extension. After all, it was aluminum. It wasn’t going to break under anything I could come up with that would be a reasonable magazine test. But it was going to get gouged and scarred. It would look ugly when I was done. Did I want to do that to such an attractive manufactured object? Adding to my angst was the Dawson Guarantee. I was assured by Tom Hall at Dawson that they would replace any extension that I or anyone else was unsatisfied with. (I must admit that a little voice in the back of my head suggested abusing the extension and then sending it in for a pretty replacement. I slapped it down.) In the end, I figured that ugly was worth the knowledge.

Let the abuse begin!

This scarred old Dawson still works like a champ.

The Sweeney “I can’t believe he’s doing that!” test regime started out with some dropping. Our latest club range improvement uncovered some large rocks that we’ve hauled to the side. (There’s one we dug up that’s the size of a Yugo. It has about the same performance as a Yugo, without the smoke.)

I dragged a chair over and sat there, dropping the magazines, baseplate hitting the rock, for a few minutes. Nothing broke or fell off. Then I spent a few minutes standing over the rock, dropping magazines, picking them up, and dropping them again. Still no problem.

Time to up the ante. I loaded the magazines and started over. No breakage. What surprised me was how rarely rounds launched themselves from the magazines when dropped. Some magazine styles will launch one or many rounds each time they are dropped. I’ve seen dropped hicap 1911 mags that would snap the top round 180 degrees, leaving it rim forward. (Clearing the malfunction such a round creates can take a few minutes.) I’ve seen Colt 9mm submachine gun mags spew their entire contents when dropped. The Glock mags did fine.

Sand and gravel didn’t cause any of the extensions to falter.

The poor, abused magazines, hiding in their nest, hoping the author has run out of ideas.

Dropping magazines on rocks is bound to attract attention. But if you’ve got to know, you’ve got to know.

Obviously, the rock problem wasn’t much of one for the extensions and I was getting nowhere fast. I then went to the nearby range and proceeded to drop the magazines onto a steel plate lying on the ground. After a few minutes, I came to the realization that I simply wasn’t going to uncover any problems. To soothe my disappointment I fired the rounds that were in the magazines, and was not at all disappointed. They all worked.

I set up a pair of steel drums adjacent to the lumber retaining wall of the enclosed range and proceeded to drop each empty magazine into the sand and kick it through the “goalpost.” After a few attempts with each magazine I started over, “dribbling” each round with a series of kicks, then driving each through the “goal”, impacting the lumber wall with a sharp smack.

On inspection, the magazines appeared fine. The extensions were intact and securely attached, and the feed lips of the magazines were unharmed. I wiped the exterior sand off with my hands, loaded them and fired the rounds, again without failure.

Time to get serious. I loaded the magazines to start over. On the first kick, I left the magazines where they were and went back to the truck. Deliberately kicking a loaded magazine with running shoes on is not a good idea. As a matter of fact, it hurts. I put on a pair of boots and went back to kicking. After a good aerobic exercise session, I wiped as much of the sand off on my trousers that I could and got to shooting. Does anyone care to guess how many failures I had? All of you who bet against “none” owe your shooting buddies a soft drink. That’s right, none. At this point, having fired enough practice ammo and photographs for the day, I packed up and went home.

Once I’d done this, Robin Taylor, the editor of Front Sight magazine, asked me a sneaky question: “Got any aerosol gun cleaners?” Sigh. And just what does a degreasing/ gun scrubbing aerosol do to the plastic composition of the various extensions? Unfortunately, I had a bunch of cleaners on hand and a limited supply of extensions. I could not test all extensions with all chemicals. On the good side, I was positive that the makers of the extensions went to some trouble to find polymers that would shrug off common firearms cleaning chemicals. (After all, they are going to be gun parts, right?) And, we all know what to expect from the Dawson extension, right? Any chemical cleaner that will attack the aluminum of his extension is something that will probably dissolve both the Glock magazine tube and you in the same few seconds. What you can buy over the counter won’t have any effect.

So I dragged out the cleaners and installed the slightly scuffed extensions on my own magazines. Rather than kick the magazines I simply hosed the extensions and let them sit wet with the cleaner to dry in the warm air of the springtime breeze at the range. Once they’d been through the bath three times I proceeded to repeat the drop test. And to no great surprise, none of them failed. The pattern of what appears discoloration is simply the pattern of the cleaners as they evaporated off the plastic. The various extensions were not actually discolored, as wiping them with a clean cloth brought them back to their original (now scarred) appearance.

So I now have a bunch of really high-capacity Glock magazines for use in competition. I’m particularly fond of the Dawson extension, both in its design and this one’s current scarred condition. Anyone who looks at the scuffs and gouges on it has to figure that I’m some sort of lunatic who will do anything in practice or at a match in order to gain a few extra points or a second off my time. Looking at the Dawson they have to wonder if winning would be worth the effort of beating me. Let them wonder.

Under hard use, the bottom of the notch on the magazine tube will get peened. The usual cause is slamming the magazine into the frame when the slide is locked back. The magazine rides up past the catch, and the bottom of the notch bangs against the bottom of the catch. If the peened area causes a problem fitting it into the gun, you can use an exacto knife to cut away the excess. If the magazine otherwise locks in place and functions as designed, Glock will not replace it just from peening.

While the magazines may last forever, the mag catch doesn’t, if you take it out all the time. This is the mag catch from the training gun I used in the Glock armorer’s course. Looks like a squirrel’s been at it.

Springs will always be with us. If you are going to go and do some really high-volume practice or competition, you should invest in spare magazine springs.

The problem isn’t leaving them loaded but in using them. The repeated cycling is what wears out a magazine, not leaving it stressed. (At least not good ones.) I’ve had good luck for a long time with Wolff springs and recently with ISMI springs. I’ve been putting tens of thousands of rounds through an ISMI recoil spring for a 1911 that has not showed significant compression set yet.

Swapping magazine springs is simplicity itself. Disassemble the magazine, pry the old spring off the follower, insert the new spring in the same orientation, then reassemble. The trick lies in knowing when to replace your spring. You could just do it every few years. After all, at less than $10 per spring, if you replace them once every couple of years, you’re still spending less on springs than you are on primers for reloading the ammo you shot in those same magazines. And springs don’t cost anywhere near $10 each. The current Glock armorers catalog lists them at $3 each, with the usual shipping and handling charges.

At three bucks each, you should simply buy two spares for every magazine you own, and a couple of followers per caliber to round out the order. If you have magazine extensions on your tubes for competition use, you can get replacement springs from the makers of the extensions, or oversized springs from ISMI or Wolff and cut them to proper length. When cutting, don’t go by overall length (the old ones may be shortened from use); rather, count the coils. The Dawson spring (which simply happens to be the one at hand as I type this) has 11 coils. So, when trimming a new, over-sized spring, cut it with sidecutters to 11 coils and bend the bottom coil to match the original.

The classic symptom of weak springs in 1911 pistols is when the otherwise reliable pistol stops locking open when the magazine is empty. That is also what Glock tells us in the armorer’s course: if it locks back, it is bad. If it doesn’t, it is fine. The dynamics of the Glock are slightly different, and what you’ll likely see are feeding problems.

If you start getting rounds trapped under the slide and against the feed ramp, your spring is getting tired. The magazine extension baseplates come with their own, longer, springs. These springs have to lift an even heavier stack of rounds when you shoot. If you are going to use extended magazines in competition, invest in a set of spare springs and keep them with you.

As for the followers, you will be hard-pressed to wear them out. It is common for other pistols to have aftermarket followers that offer higher capacity. On some designs, changing the follower gets you one more round. No so the Glock. Can you wear out a follower? Theoretically, yes. I haven’t seen one yet, but there has to be at least one high-mileage follower out there in constant use in a police training range that is ready to quit. They last so long that no one has been able to create a market for replacement followers, as there is in the 1911 world.

Abuse, however, is a different case. Sergeant Armando Valdes of the Miami PD described to me a failure he saw with their Glocks. It seems that some officers were not content to merely let their magazines fall to the ground during qualification or training. They would actually hurl the magazine down. “I saw them throw them down. Ripped out and thrown.” He shook his head. “Gravity works. Why not just let go and let them drop?” The magazines would eventually break the tab on the follower that locked the slide back when empty. A new follower solved the problem. I don’t know what he did about the magazine tossing.

For a while, you could buy Glock magazines up to 33 rounds in capacity. Made by Scherer and Glock (and probably others, but I haven’t seen them) the ones I tried all worked fine. While the Sherer magazines were offered on the open market, the Glock 33-round mags were strictly law-enforcement only. Not that there was a law against them (at least not until 1994-2004); Glock just felt they were only suitable for LEO use and sold them only to departments. We can now buy them with wild abandon, at least the Scherer magazines. Glocks are still controlled by Glock. Do you need them? As much as I hate to say it, probably not. They are quite large, bulky, and too long to pass muster for USPSA competition. But they are fun.

The Glock LEO 33-shot hi-cap built for the G-18.

All the old tricks for getting magazines to feed reliably went out the window when Glock mags hit the scene. In the old days (and even today for some magazines) we’d polish the inside, measure and bend or adjust the feed lips, deburr the inside of the tube and the follower, lube or coat the inside with some sort of nonsticky lubricant, and install extra-power magazine springs. Some magazines even came in for bending, sanding and polishing the exterior as well. I still remember the maker of my Caspian hi-caps squeezing the tube in a vise and then whacking it with a rawhide mallet to get the tube straight enough to drop free. Definitely something the faint at heart should not watch being done.

The only one of those that applies to Glock magazines is installing an extra power or new spring. That and keeping your magazine clean is about all you can or need do to keep your magazine working 100 percent of the time.

If you shoot at a range composed mostly of sand, your magazines will get gritty after being dropped a few times. At matches, you’ll see competitors pumping brushes in and out of their magazines to keep them reasonably clean during the match. When they get home they’ll strip and clean their magazines. You should, too.

Inspect the follower for ground-up bits of polymer that might bind it. Instead of a file, use a sharp knife to trim the bits off, like clipping stray threads from your clothes.

Sometimes when installing the capacity extension, you’ll run into a small problem: you don’t get any increased capacity. When Glock designed their magazines, they weren’t concerned with aftermarket capacity-increasing baseplates. (They probably view them as yet another point that proves just how strange the American shooters can be.) The dimensions of the bottom interior of the Glock magazine tubes are kept within tolerances that allow all Glock parts to fit and work. If your magazine doesn’t allow the full increase, the insides of the extension and the tube aren’t lining up. First, try the extension on another tube and see if it works there. If it does, then stick with it. If not, then you’ll have to find the side that has the ledge and carefully bevel the corner there so the follower can ride down into the extension for full capacity.

If you want the biggest, the 2- and 33-round magazines, the only way is to get them from Scherer. Glock sells their “big stick” mags only to police departments.

Just when you thought the warning labels were maxed out, here’s another one.

If you have a magazine that sticks and doesn’t drop free even though it is a dropfree design, don’t go sanding it. While sanding is an accepted method of getting a steel magazine to gain clearance, the polymer of the Glock magazine won’t sand. You simply kick up a fuzzy surface of fiber edges (sort of like velcro in appearance) and end up making your magazine even bigger and more of a problem.

What to do if a drop-free sticks? One solution I’ve heard of but never tried (I haven’t had a drop-free stick on me) is to insert the offending magazine backwards into the gun overnight. By stuffing it partway (it won’t fit far) frontto-back you’re either squishing the magazine or stretching the frame and creating the clearance needed. (If it works, thank Robin Taylor. If it doesn’t, swap magazines with someone else.)

One solution offered early in the Glock existence was to use an automobile rubber shine product to slick up your magazines. That one I never understood. First, if it is slick enough to go easily into the gun, how are you supposed to grab it to pull it off your belt? And what happens when your gooped-up magazine hits the dirt, sand, mud or gravel of the range floor?

At many matches, you’ll go dashing through each stage, leaving a trail of dust, empty brass and expended magazines behind you. Especially if you’re shooting with 10-shot magazines in Production Division and going through a large field course in a USPSA match.

Forty or 50 rounds later (I’ve heard of stages as big as 130 rounds!) you’ll have your half-dozen magazines scattered behind you. You want to be sure and get all yours back.

So mark your mags. The easy way is to disassemble them and then degrease the baseplates. Once clean and dry, give them a coat of spray paint. No, it won’t stick very well, nothing will, at least not to Glock parts. But enough will stick that you can tell which ones are yours.

The paint job can be renewed as needed and changed if too many others start using that color. You should also number your magazines. If you get into the habit of numbering them and then using them in numerical order (#1 to start, reload to #2, reload to #3, etc.) you can track down malfunctions. If you have an intermittent problem, but it always happens to #3, you can then test your adjustments on #3. By narrowing the problem to a single magazine you make your problem much less of one. If, on the other hand, you have an intermittent problem but it never seems to happen to the same magazine twice in a row, then you still have a useful bit of information: the source is probably not your magazines.

A Glock LEO orange training baseplate.

One advantage to the orange baseplates is the ease with which you can mark them with a felt-tip pen.Too bad they’re Law Enforcement Only.

Number your magazines with press-on numerals. Again, they won’t stick for very long, but you aren’t looking for a forever solution. You just want something that will stay on well enough to let you know which ones are which and that can be easily renewed when it falls off.

One trick I use on other magazines that doesn’t last nearly as long on Glock magazines is to degrease the mag, stick the number on, then give a light overspray of clear polyurethane. The degreased surface lets the numeral stick. The polyurethane seals the edges of the adhesive on the numeral. Unfortunately, while the method works for months of use on steel magazines, the Glock tubes flex enough that the numerals come off in a few range sessions. The lack of adhesion to plastic/polymer is one reason some shooters use aluminum basepads for their magazines. Aluminum holds paint, and the stick-on lettering adheres well enough (especially with the poly overspray) that you can get months of use out of them before having to scrub and reapply.

One of the shooters at our club uses a label making machine, the kind that spits out a strip of adhesive-backed plastic label material. He prints up his name and the magazine number and applies it to the side of his magazines. When they get too tired or scarred he scrapes them off and applies new ones.

Or you can use a paint pencil, a metal tube that works like a felt-tip pen, but dispensing paint. The paint pen lets you write on surfaces and thus number them.

Glock makes bright orange baseplates for use in law enforcement training. By marking training-use only magazines with orange baseplates, a department can ensure that the heavy use and occasional abuse those magazine receive won’t be cause problems on the street. The training mags get the dropping and kicking, and the heavy exposure to dust, mud and rain. Meanwhile the duty mags are tested, then left loaded in their pouches, protected. The bad news? The orange baseplates are LEO-only, and not for sale to the general public.

Could you paint your baseplates? (The Glock orange ones are colored by the use of dyes in the mixed polymer.) Yes. If you find a paint that sticks and stands up to range use, let me know, will you?

Having reliable magazines is just part of the equation. Getting them into the gun as quickly as possible is the other part. While the basic design of any hi-cap magazine/ pistol makes reloading easier than single stacks, funnels help. The tapered shape of the top of the magazine, and the larger than that top entrance in the frame, makes getting Glock magazines (and other hi-caps) into the frame a pretty smooth operation. But you can always make things better. If the magazine opening is larger, or larger and tapered, then getting the magazine in is even faster. And in some matches, faster is better.

The smallest “funnel” I have on hand is from Scherer. A simple plastic wedge that fits into the hollow rear of the frame, it helps guide magazines into place. Another simple method that also adds weight is the Seattle Slug from Taylor Freelance.

The small Scherer mag funnel, inserted in the hollow of the frame.

The Seattle Slug in a G-34 for competition.

The Seattle Slug comes in two styles, brass and aluminum. The aluminum is light, and doesn’t add much weight, but the brass adds a significant amount of weight to the Glock. Yes, light weight is one of the virtues of the Glock, but what is a virtue when you’re carrying all day can be a liability when you’re shooting in competition. The extra weight of the Seattle Slug helps dampen recoil, and the wedge lower portion guides your magazine on reloads.

In talking with Robin Taylor I found another use for the Seattle Slug. It seems police officers in his area have started using it, not to hit suspects with (very bad idea, by the way) and not just as an aid to speed-reloading. They plan to have it on their pistol as a tool to break car side windows. An officer in their area bought one right after he had to break a car window, and in the process of using his Glock sans Seattle Slug his magazine came out. The hard point of the Slug breaks windows and leaves the magazine intact.

For some competitions, bigger is better. (And for some competitions, no changes are allowed.) For the bigger ones, you need to go to something like the Grams or Arredondo magazine funnel. They circle the mag well, offering a funnel on the complete circumference of the frame.

The Grams comes in tungsten for a real addition of weight. For real speed, Dawson offers their Ice funnel. The body of the Ice funnel is aluminum but the inner face, where your magazine impacts it when guiding, is a slick polymer. It’s a big hole you can’t miss, and a slick surface that your magazine can slide over as you do your high-speed reload? How can life get better?

The Seattle Slug locked into the frame. The shipped polish is so good you can see my hands reflected when I took the photo.

Not all ways of getting more ammo into your Glock are the same. And some will be required skills in some competitions.

Reloads fall into two categories with two approaches in each. The two methods are Competition/ Speed reload, and Tactical/ Retention reload. In all methods, you keep the gun high enough that you can watch what you’re doing and still keep an eye out for trouble. You don’t want to be reloading down at belt level, with your eyes off the world around you.

The speed load is the one we’ve all seen and marveled at. Properly done, you hardly have time to realize that the shooter has reloaded. Properly done, the down time between shots can be as small as a second flat. The competition load goes like this:

When the competitor decides he (or she) needs more ammo, he lets go with the off hand and begins reaching for the next magazine. As he reaches, and if his hand is small enough to require it, he shifts the gun slightly and pushes the magazine release button. As the first magazine falls free, he is already grasping the next one. Before the magazine hits the ground, the new magazine is off the belt, inserted and slammed home.

The variant of the speed load used in law enforcement has one difference: Here, the magazine button isn’t pushed until the shooter has ALREADY grabbed the next magazine. A small detail but an important one. In the rough-and-tumble of an actual fight (as opposed to a competition) you can lose magazines. It would be a real shame to dump your only magazine, to then find out your spares have fallen and can’t be found.

If you’re going to carry or compete with a Glock, you have to carry spare magazines somehow. A belt holder is so much more convenient than your pockets.

The important detail in the speed load is to be fast-slow-fast-slow-fast. That is, get your hand to the next magazine fast. Slow down enough to be sure you have a good grip on the magazine. (I’ve seen more than one shooter throw a magazine across the range, from being fast but not having a good grip.) Get the magazine from your belt to the gun fast, then slow down to make sure it is lined up properly. (And I’ve seen shooters throw a loaded magazine past the gun, trying to insert it at warp speed.) And finish by inserting it fast and in one motion. (Don’t insert it, then take your hand off it, and then slam the magazine home. Don’t take two or three motions to do what one can do.) Done at top speed, it doesn’t look like a good shooter is slowing down, but they are.

In the old days, we used to try and get photographs of ourselves with the classic speed-load elements: Two fired empties in the air, old mag in mid-air and new mag in the left hand on the way to the gun. And no cheating by shooting one-handed already holding the spare mag!

A hi-cap carry setup for competition or concealed carry. With a G-17 on the other side, this shooter has 64 rounds ready to go. (Dawson on the left; Taylor Freelance on the right).

Tactical/Retention is different. Here, you aren’t getting reloaded as fast as possible. You’re reloading during a lull, or you’re reloading on the line between firing strings. Or you’re in an IDPA match and you aren’t allowed a speed load. Why not? Simple: at the range you can pick up magazines and use them again. In a gun fight or in combat you may not be able to get back to where you dropped that magazine.

Infantrymen in combat units often have “dump bags,” a bag where they can drop off their magazines once they’ve emptied them. Reliable magazines are not always easy to find. And you can never carry enough spare ammo, so ditching the few rounds left in a magazine (swapping mags before you run dry) is a bad thing. And dropping magazines onto the ground subjects them to dirt, dust, mud and potential damage. The less you abuse them, the longer they’ll last.

So the tactical reload keeps your magazines on your person and saves every single round of ammo for future use.