Minsker’s Mettle

The chipper kid was talented and a friend to all fight folk from the time he was nine years old or so. When he became a national amateur champ, even his local rivals and their coaches were proud. This ran in Willamette Week on April 2, 1984.

He doesn’t drink, snort, shoot, or smoke, and he fights like a mongoose. His biggest dissipation is pike fishing in filthy weather. He’s fast whether he’s thinking, talking or fighting. He likes to train. He’s a boxing manager’s dream.

These things, however, had nothing to do with the reason the New York modeling agency Click picked twenty-one year-old Andy Minsker of Portland. Click grabbed him because he has a face like a bright-hearted cougar, and coast-to-coast shoulders on a 5-foot-9- inch frame that carries a scant 125 pounds. The Click scouts stumbled on him in a magazine photo of the 1983 Sports Festival. They weren’t interested in Minsker’s ranking as the leading featherweight boxer in the United States. They figured he’d be a great clothes rack.

In February Minsker was training at the high-altitude Olympic Camp in Colorado Springs. No problem for Click. The agency flew him from Colorado to New York for three days of fashion photo sessions and paid him $600 a day. The results will appear in this summer’s issues of Vogue, Esquire, Gentleman’s Quarterly, and Interview magazine.

“It was a snap,” says Minsker, “And it has nothing to do with boxing, so I get to keep the money.”

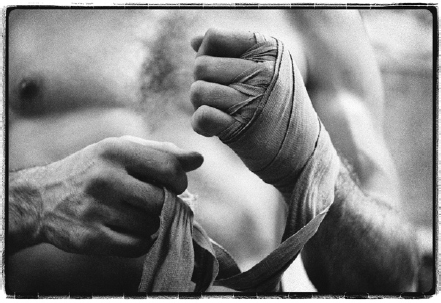

“Those clothes they photographed me in were all Italian designer styles. Hard to describe,” he grins, “but nothing I’d ever feel comfortable wearing.” He’s comfortable in jeans or dress sweats, but some scouts claim that he looks best in boxing trunks, knobby and skinny but “moving as light and true as a Mother’s prayer.”

Such scouts are the discreet connoisseurs who haunt amateur boxing, searching for potential moneymakers for the professional ranks. The word is out on Minsker. “The kid has a thousand pretty moves,” says one of these veterans.

What makes Minsker so good? He can slug without getting slugged back. It sounds simple, but it’s not so easy. In the fast and smart 125-pound division, it means that Minsker has excellent defensive skills. He can slip and block punches. He has a charismatic style, economical but flashy; a grace that gets the job done but keeps the audience soaring with amazement. He tends to counterpunch, luring his opponent into an attack that Minsker can evade and capitalize on simultaneously. It’s a strategy that demands intelligent composure under fire as well as superb reflexes. Even more marketable is Minsker’s power. In the past two years, this speed specialist has developed a knockout capacity that has him stopping and dropping opponents at a ferocious clip. His record now stands at 225 wins and 22 losses in 13 years of boxing. “My goal,” he says, “is to win 250 before I lose 25.”

These skills won Minsker the 1983 National Golden Gloves Championship and the 1983 Amateur Boxing Federation crown. Ranked No.1 in the nation, Minsker has a guaranteed shot at the U.S. Olympic trials in Texas this June, and the odds are good that he will represent the United States in Los Angeles. A lot of wise money says Minsker will take the Olympic Gold.

As national champion, Minsker is already in the big leagues if he chooses to turn pro. Each step toward the Olympics ups his ante. So far his international competitions have him hammering three weight divisions in New Zealand, flattening a crew of Scandinavians, and stopping the British Commonwealth and Yugoslav champs with first round KOs.

Nobody in a boxing ring is born knowing how to do these things. The word “talent” doesn’t begin to explain how it happens. Heredity can help: Andy’s father, Hugh Minsker, was the 132- pound U.S. Olympic alternate for the 1954 games. According to his coach, Leroy Durst of the Multnomah Athletic Club, “Hugh was the best pound-for-pound fighter in the country at that time.”

Minsker says his father has never pressured him to box. “For a long time I didn’t even know my dad had boxed,” he says. “We kids used to bang his trophies around playing, but I never made the connection … I started out at the Mt. Scott Community Center gym when I was eight years old, just because my step-mom wanted me to have something to do after school. Chuck Lincoln was the coach then, and Ed Milberger was the assistant coach. I remember Chuck saying, when I first went in, ‘So you’re Hugh’s boy!’ but I didn’t make anything of it. I boxed for more than a year before I found out about my dad.”

Minsker is quick to point out that there is a good coach behind every fine athlete. “I have to give all credit to my coach, Ed Milberger. He’s been with me since the beginning. He’s driven thousands of miles to get me to tournaments and fights. Ed is one of the most under-rated amateur coaches in the world. He’s taught me from the beginning and if I ever make it big I’ll make it worth his while.”

Minsker gained power after he had crumpled his right hand on somebody’s head nearly three years ago. He fought and won many times with the damaged hand, and explains that he couldn’t afford the surgery and didn’t want to take time off to allow the hand to heal. “That would have washed me out of ‘84,” he says. “You’d get awful rusty in six months. It was then,” he recalls, “that Ed took me into the gym and showed me how to plant to throw a left hook. I’d always been so skinny I never thought I could punch hard. That was the turn around. I’ve been stopping guys ever since.”

Milberger remembers, “I also pointed out to Andy that you were a lot less likely to hurt your hand hitting the belly than the boney head. Andy started working the body pretty good after that.” After winning the 1983 Golden Glove nationals in March that year, Minsker finally had the required surgery. Seven months and several international victories later, he won the ABF nationals in October.

As one of the Amateur Boxing Federation Elite-Operation Gold boxers, he was able to stay uninterrupted at the intensivetraining center in Colorado Springs. But he prefers to go to the camp for a few weeks before each bout.

“It’s cold up there,” he complains. “It’s hard to run in ice and snow. And there’s nothing to do. You can’t box 24 hours a day.” When he returns to Portland he lives with his parents, takes classes at the Portland Upholstery School (“It’s a good trade for after I retire from the ring.”) and works.

Minsker’s job, five nights a week and most weekends, is coaching the boxing team at the same scarred old gym in the Mt. Scott Community Center where he began. At the ‘84 Oregon State Golden Gloves Tournament in the Marriott Hotel in February, he was the youngest coach present. His team took two state championships and the second-place team trophy.

With the Olympic trials scheduled for June, this spring is a time of pressure for all the competitors. It’s natural for them to wonder if they’ve chosen the best route. “Maybe I should go and stay in camp for the big push,” muses Minsker. “There’s a lot of political juggling in the amateurs. That’s the way of the world. If they like you, you’ll go some place. The fortunate thing about an Olympic year is that it eliminates politics. They’re going to take the best they’ve got. They want to win twelve gold medals. They’re going to take a guy who can punch and who can take a shot to the chin. I don’t box amateur-style. I don’t take punishment. Even in a tough fight, I don’t get hit a lot. If they taught more power and how to slip punches, the Russians wouldn’t run us over all the time. I don’t throw punches just to make points. I’m working now to get the science of hitting them on the jaw and dropping them.”

Sometimes you count the cost. “It’s hard to hang on to a girl friend when you’re gone so much,” says Minsker. “You go out with somebody for a while and everything’s great, then you go away for a month. When you get back she’s going out with somebody else…. Maybe it’s bragging, but the girls I’ve dated have been just flat-out beautiful, and that’s trouble. I don’t have anything except boxing clothes, walking suits. Every time I go anywhere, other guys will start looking at my girl, and then they figure out that I’m a boxer. If they’ve been drinking at all, they always decide to pick a fight. Seems like I’m scared to death the whole time.”

There is also the future to dream about. “There are people who fly in from Detroit and Houston to see my fights. I’ll make the Olympic team and then, if the money is right, I’ll turn pro. It never used to appeal to me, but now it seems like I’ve put so many years into boxing I ought to try to get something out of it. I’d like to fight for four or five years, then retire when I’m 26 or 27, go into business for myself. Hey, I’ve worked twice as hard in the last 12 years as some people work all their lives! If I retire when I’m 26, it’ll be like another guy retiring when he’s 62. I’d love to stay in Portland, but probably nobody around here could afford it. Maybe if six or seven businessmen got together to bankroll my contract….”

Hugh Minsker worries, “The way things are in this state, I’m just afraid that if Andy ends up winning the gold he might end up turning his back on Oregon and going to Texas or someplace.”

It’s not just a financial problem. There is a chilling lack of recognition for boxing, amateur or pro, by reporters in Oregon.

“Face it,” says Andy Minsker, “recognition is the main reason for fighting amateur.”

A state champion for six consecutive years before winning the national title, he can’t help taking it personally.

“Well, I’m a white guy,” he grimaces, “and people don’t think white guys can fight. And usually white guys nowadays can’t fight. Maybe that’s part of it. But one way or another, the people here don’t think I’m for real. They don’t understand that I’m No.1, and they’re going to have somebody representing them at the Olympics. They’ll give all sorts of attention to the 14 year-old girls in rhythmic gymnastics, and I’m not saying they don’t rate; they do. But nobody knows who I am.”