Epilogue:

Imagine A Square

A good boxer is a miracle of chaos mathematics. When I think about the complex variables required to bring the right kid to the right coach in the right place at the right time, I am amazed that it ever happens at all.

It’s a crapshoot for a novice walking into a gym for the first time.

You want to learn to box, you need a coach to teach you. But not all coaches are created equal. An experienced fighter in a new town knows how to call around and find out who to work with. But a greenhorn rarely has a specific coach in mind. They choose a gym because it’s on their way to work or school, or they find it in the phone book. They assume that any coach will do. In this gym, once a kid talks to a coach, he’s linked to him, belongs to him. The coaches are rivals, possessive of their fighters. None of the other coaches will even pass the time of day with the kid for fear of being accused of “buzzing” another coach’s fighter—the fistic equivalent of cattle rustling. They will slag another coach behind his back, sneer at his failings as revealed in the stumbling footwork or flailing elbows of his fighters, but they are bland and civil face to face. They would sooner fry than tell a kid he’s accidentally picked an idiot instead of a real coach, and thereby, in the first thirty seconds of his boxing career, doomed himself to failure.

The kid came through the side door on a winter afternoon, just off the school bus. He was a skinny thirteen or so, with a kit bag in one hand and a sack of books hanging on his shoulder. He stood looking around with a hungry curiosity we’d all seen before. He wanted to box.

I was warming a folding chair against the wall with the other gym rats—retired guys who were there just to get out of the rain, parents and reporters and other such scholars. We all pretended not to see the kid. If he came up to us, asked a question, one of us would have to answer and none of us wanted the responsibility of pointing him to one of the coaches in the gym that day. A half dozen or so new fish between the ages of eight and thirty strode through that door in any given month, and I wasn’t the only chair jockey who sweated until each ones’ fate was determined.

This particular spit-crusted, roach-infested storefront gym has five separate volunteers willing to call themselves “coach", but two of them are ignorant posers. At best you’d call them beginners. One of the others was a fine boxer himself, but he couldn’t teach a fish to swim. There are two skilled, experienced coaches in the gym: call them Clyde and Ruben. They are both fine with the basics, but Clyde teaches the long-armed jab-and-move style, while Ruben favors the inside techniques of plant-and-hook. They are grudgingly respectful of each other, but they are both too proud to go looking for fighters. They’ll ignore a newcomer unless the kid marches right up to them. The wannabe coaches will greet them at the door like used-car salesmen.

This kid walked in the door knowing none of this, probably knowing only what he saw in a Rocky movie or what an uncle told him about the old days. He stood there gawking, oblivious to the minefield of micro-politics that surrounded him, absorbed by whatever fantasy or personal torment had driven him through the door. By some accident of luck, the lesser coaches were busy with their fighters and didn’t swoop down on him.

It was cold outside and the big front window was steamed over so the street traffic was only visible as sliding light and the two older pros skipping rope near the glass were blurred silhouettes. The air was filled with rhythmic hisses, pops, drum rolls, and wet, staccato smacks that can bewilder an ear unfamiliar with the sources. Some kids come in trying to look tough, but this one just looked eager. He knew what he wanted, he just didn’t know who to ask.

The bell rang to end the work round, and the noise fell off. One of the pros near the window let his rope drop and took two steps toward the kid. “Help you?” The kid lurched forward and started talking fast. I couldn’t hear what he said but his voice hadn’t changed yet, still thin. I sat back and began to breathe again. Another lucky break. The pro was knowledgeable and wouldn’t steer the kid wrong. Sure enough his big head nodded slowly and he said, “You want to talk to Clyde.” Then he walked the kid over to the heavy bags where Clyde was supervising fighters, and introduced him.

In his late sixties, Clyde could probably still whip anybody in the gym. He’d retired undefeated as a pro some forty years before and hadn’t added one extra pound to his rangy middleweight frame in all that time. His neat silver beard rode up into the creases and folds of his mahogany cheeks. His battered nose detoured in the middle and spread out slightly left of center. His eyes had a blue sheen hinting at the glaucoma his doctors were fighting. But he could still see well enough.

On a bad day Clyde would have snorted derisively and told the kid to get somebody else to work with him. This was one of Clyde’s good days. He wasn’t squinting or shielding his eyes. His walk was limber so his hip wasn’t bothering him. He looked at the kid. The kid looked up at him.

The kid would have been just as anxious to please one of the posers if fate had steered him that way. He couldn’t know that Clyde had taught dozens of national amateur champs in his time. Clyde asked the standard questions: How old are you? What do you weigh? Does your Mom know you’re here? How does she feel? How about your Dad? You do any other sports? Are you right or left handed? He was listening for attitude as well as answers.

There are excellent coaches who will work their hearts to shreds teaching anybody who comes through the door. But that’s not Clyde. Clyde says, “I ain’t got time to waste and I don’t need the aggravation.” But somehow the scrawny kid passed Clyde’s first test. Probably said “Sir” fifty times. A few minutes later the kid had shucked down to a T-shirt and sweat pants and was doing jumping jacks while Clyde put the finishing touches on his other guys’ work for the day.

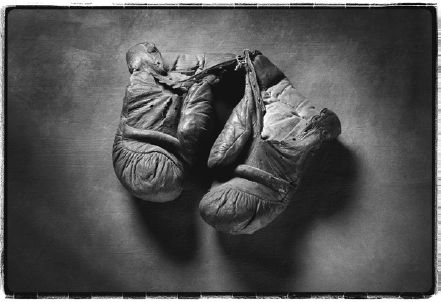

The kid’s kit bag had wraps spilling out, and brand new bag gloves peeping red through the open flap. When Clyde ambled over he told the kid, “You won’t need that stuff for a while.” Clyde introduced the kid to the big mirror on the wall. The glass is so coated with dried snot and spit and congealed sweat that if you stand too close your face gets lost in the haze, but this mirror would be the kids’ chief tool and friend for weeks if he stuck it out.

The other gym rats were focused on the sparring in the ring, but the first lesson in geometry and physics was coming for this kid, and I couldn’t take my eyes away. His own center of gravity was about to be revealed to him. Clyde always begins the same way. With the kid standing six or eight feet from the mirror, Clyde tells him to take a stance, set his feet. Then, using one bony finger, Clyde pushes on his shoulder and knocks the kid off balance, has him scrambling to stay upright. He lets the kid try his feet in different positions. “Are you solid?” Clyde asks, and the kid nods. Still the lone finger tips him over easily. “Guess you weren’t solid after all,” says Clyde.

He points at the gritty floorboards in front of the kid and says, “I want you to imagine a square.” Looking down, the kid seems to see a big, chalked square. Defining the size of that square, Clyde shows the kid where to put his feet inside it, how to set them, how to check his position in the mirror. Then he uses his index finger to push on the boy’s shoulder. The kid doesn’t move. Clyde pushes at him from different angles, but with his feet in the proper position the kid’s balance is right and he can’t be tipped over. He is solid.

No matter how often I see this it still gets me—the first time a kid meets a coach, the first lesson. It’s a brief moment when the glass clears and you can see possibilities branching into the future. An ignorant coach is a bad teacher who can injure his students. A good coach is the opposite. Every skilled boxer met a good coach along the way. Considering the many alternatives it’s a kind of miracle when it happens.

The kid was grinning, delighted. He hadn’t clenched a fist yet, or moved a single step in any direction. The lesson would go on for another hour, gradually adding movement and form. If the kid comes back for more, a complex world of effort and pain, pride and beauty is open to him. Maybe he’ll walk out the door and never come back—take up soccer or video games instead. Still, in these first five minutes he’s learned something he didn’t know and won’t forget. He may never realize how much luck it took to get him this far.