Introduction:

Sometimes the Subject Chooses You

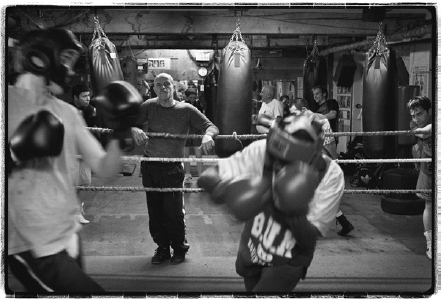

Boxing is simple. Two unarmed volunteers, matched in weight and experience, face off in a white-lit square. It is ritualized crisis, genuine but contained. At its best, a bout is high improvisational drama and the boxers are warrior artists. When it falls short of perfection, which is almost always, the failures are interesting in themselves. Horrifying or hilarious, and all points between, no two fights are alike. What happens in and around that mislabeled ring is a potent distillation of everything human.

This book is a sampling of all I have chased after, tripped over, been blind-sided by, learned, un-learned, mistook, admired and detested over three decades of writing about the sport of boxing.

These dispatches span an era ranging from the brilliance of Sugar Ray Leonard to the long decline of Iron Mike Tyson and the rise of women in the ring. Also included are stories of amateurs and little known club fighters—the blood and bones of the sport. The 1980’s and 90’s, and the early years of the 21st century were decades when tribal casinos gradually rescued the individual art of boxing from burial under the avalanche of corporate team entertainments, and when strenuous, often futile, efforts were launched to increase safety and to regulate the anarchy. It was complex, usually fascinating and always messy.

When I was a kid, back in the middle of the twentieth century, boxing was part of the blue-collar dream life of America. Boys learned the sport as amateurs in school or church or community center clubs. Every newspaper covered it. And, long before television, the professionals came to us on the radio.

On warm Friday nights with radios propped in open windows and families out on porches and stoops, the scratchy voice of the ringside commentator filled whole streets. In some neighborhoods you could walk block after block and never miss a round.

My family was pretty typical in that the men were interested in boxing and my mother disapproved. She called it barbaric and vulgar. That was enough to intrigue me.

I’ve never been one to yearn for the good old days. That post WWII America was a rough place, as I recall. Racism and sexism were insistent and institutional. Spousal battery was condoned. The smacking and whipping of children in school and at home was expected. Gangs were common. Brawls boiled up in streets, playgrounds, taverns and workplaces.

At the time, boxers struck me as peculiarly civilized. They didn’t screech or holler. They didn’t use knives or bicycle chains or chunks of plumbing, and they only fought when the bell rang. When it rang again, they stopped. Amazing. Still, I believed that, being a girl, I had no access to the place where the rage was trained and restrained.

Muhammad Ali erupted into the general consciousness while I was in high school. If you knew nothing else about boxing, you knew Ali. Early on I was one of the many who found Ali offensive. He violated the tradition of modest, dignified champions I’d learned to respect. But he won us all over eventually, and became an indelible icon of humor, beauty, skill and defiance. His long career reached deep into my adulthood. For me, his physical decline tangled the bewildered awe of my childhood with a grim adult awareness of terrible consequences.

In 1980 I married Peter Fritsch, who, among his other interests, was a boxing fan. Pete casually opened a door I’d assumed was a brick wall. One day when he had to be away, he asked me to watch a televised fight and tell him what happened. When he came home I was ready with three pages of notes, prepared to deliver a round-by-round account. Turned out he just wanted to know who won.

Until then I had only seen the professional sport on television. Pete took me to a live fight card. Looking back I can see that it was an ordinary club show, but I was electrified. It was a plunge into one of the great mysteries—the nature of violence.

From that night on I needed to attend every match in reach and watch every punch thrown on television. I studied boxing books and magazines. The boxing scene in my hometown, Portland, Oregon, was lively in those days, but the coverage in the daily newspapers struck me as sparse and grudging. The sports pages were dedicated to team games and golf, and seemed to actively disapprove of pugilism. It burned me, seeing people pour hope, energy and passion into the ring and yet receive no recognition.

By then I’d published two novels and some short stories. I called myself a writer. I decided that if I wanted local boxing written about, I’d have to do it myself. In early 1981 the editor of Willamette Week, a local alternative newspaper, agreed to print what I wrote about the sport. That’s how it started for me.

The same daily reporters I’d criticized patiently answered my stupidest questions, and they snatched me back several times when I was trying to march off some journalistic cliff or other.

My husband, Pete, was not a writer, but he loved the sport and he enjoyed going to the fights, teaching me, discussing it endlessly. In gratitude for his support, I added his name to my byline in 1982 and 1983. Our marriage ended in 1984 and Pete went on to other interests. I stuck with boxing. Pete has graciously given his permission for my name to appear alone on four articles in this book, which were originally published under both our names. Those pieces are: “The Unhappy Warrior,” “Buckaroo Boxing,” “Beauty and the Beast,” and “Vice and Virtue.”

When I first started, boxing was known as “the last male bastion,” and I figured writing about it was a daring, difficult thing for a woman—right up there with teaching cobras to samba or getting shot out of a cannon three times a day. But my vanity was soon flattened by the fight folk who didn’t care whether I was female, male, or a magenta-rumped baboon as long as I got the job done.

This mania for the task at hand contributes to the inclusive nature of the sport. Race, gender, religion, size, age, education—none of it matters if you are serious about the work. Of course the minute you flub, any suppressed prejudices will surface in virulent epithets. This pattern is part of boxing’s Newtonian doctrine of cause and effect and should not be taken personally. I’ve reason to be grateful that redemption is seldom more than a hefty dose of crow and three or four desperately honest efforts away.

In this era when the sport is maligned, marginalized and ignored, its practitioners are eager for anybody who might provide coverage. Boxers, trainers, coaches, corner men, managers, officials, all take pains to help me and every other reporter who wanders through.

Back in 1981 there was one major advantage in being a female boxing reporter—no lines in the women’s rest room. In the fairgrounds and armories where the local fights took place, there was just enough female company to dull the ominous echo built into public latrines. I might find some boxer’s mother or wife or girlfriend in there, pacing or praying or cussing a blue streak. Their inside information was solid.

Nowadays, in the flash casinos, there is some danger of being spike heeled by lawyers, or elbowed at the mirror by business execs discussing the merits of an uppercut while fixing their lipstick. Admittedly, I get a kick out of this shift in demographics.

Women were always deeply involved in the supporting roles of the sport, but I didn’t understand their potential. The only women’s bout I saw in the first few years was so awful that I bought the old fight guy dictum that women couldn’t and shouldn’t box. I never believed women lacked the strength or the ferocity, but I thought they would not accept the discipline. I was wrong again, as demonstrated by the stories included here. Even the crustiest coaches and trainers made fast U-turns the first time a girl child or a woman walked into their gym and out-worked the boys.

Boxing is dangerous, and while it is a natural venue for comedy, it is always serious. Note has been made of the verbal structure in which boxing is not a game. You do not “play” boxing any more than you “play” running, jumping, climbing or swimming. These are essential functions of our species. They are also things we do for pride and pleasure—sports. When they are done with intelligence, skill and beauty, they are arts.

It’s a privilege to serve as a reporter for the pugilistic art. The Fight Guys—male and female—strive in the heat of the white light while I sit out in the comfortable dark making remarks. Thanks to them I see mortal galaxies from here. —KD, 2008