II

Beginnings

(November 1967 to June 1968)

1.

“Dr. Leakey?”

Leakey, white-haired, gray-mustached, full in the face, looked up from the mess on his desk and scowled. For a second Carole imagined herself through his eyes—this tall, young, eager American girl interrupting the great man’s important paperwork, whatever it was—and she blurted out: “How can I get in touch with Jane Goodall? I want to work for her.” She hadn’t even introduced herself, and now she was feeling graceless.

Leakey: “I’ll give you her phone number, and you can call her up.” He scrawled a number on a scrap of paper, handed it to Carole, said, “Here. Call her.”

Carole wasted nearly all her change on the museum pay phone, and it took an hour before she finally managed to reach Dr. Jane Goodall at the Grosvenor Hotel. But Dr. Goodall had a calm, melodious voice projecting an open personality, and Carole nervously explained that she was a third-year student at the Friends World Institute, an itinerant, Quaker-run experimental college from America that was based for the year in Nairobi. She wanted to volunteer for work—any kind of work, any kind whatsoever—having to do with Dr. Goodall’s chimpanzee research, since she really loved animals. It was a friendly, polite, and positive conversation; and by the end of it, Carole had begun thinking of the person at the other end of the line as Jane. Not Dr. Goodall or Baroness van Lawick–Goodall. Baroness!

Jane had wanted to know if Carole could type and whether she liked babies. They needed a typist to support the chimp researchers at the reserve, as she called it. Occasional babysitting would be welcomed as well. Carole responded affirmatively to such queries and comments, and by the end of their talk, Jane had invited her to come visit them, her and her husband, Hugo van Lawick, at their home. She said, “Hugo and I always like to meet people before they go out to Gombe.” Carole could spend a few days there, in fact, and since Carole had felt obliged to mention the interest of her roommate, Emma, in the same project, Emma was invited, too. Jane thought they could use a second typist at the reserve.

Carole spent another hour walking back to the FWI center, which was time enough to float in a billowing excitement snagged by a frustration that focused on her roommate, Emma. Or Em, as she was usually called. Carole had made the contact with Jane Goodall. Of course, the only reason Em hadn’t was that Carole had, and only one person was necessary. Still, the frustration at having to share this glorious, life-changing opportunity with someone else, someone who was not passionate about animals in the way Carole was, took some time to dissipate.

• • •

Carole and Em spent a week with Jane and Hugo at their home in Limuru, which was several miles outside Nairobi. Jane and Hugo had begun renting the house in late February, only a few months earlier, whereupon she settled down long enough to deliver, on March 4, a baby boy named Hugo Eric Louis van Lawick. By the time Carole and Em arrived, in the first week of November, the baby was called Grub. That was an abbreviation for Grublin, a nickname the infant had acquired in the previous summer when, while the family stayed at the chimpanzee research camp, he displaced in reputation an infant chimp named Goblin Grub as the messiest eater in East Africa. The chimp returned to his original and simpler name, Goblin, while Hugo Eric Louis van Lawick became Grublin, then Grub.

Carole had heard about Jane Goodall and the Gombe chimpanzees before she went to Africa. She was on Christmas break during her first year in college, spending time with her second mother, who said something like: “Oh, we must watch television this evening. It’s Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees.” That was the first National Geographic television film about Jane Goodall, broadcast by CBS on Wednesday evening, December 22, 1965. Carole was, along with 20 million other American viewers, entranced by that shimmering vision of the brave young Englishwoman. Leggy. Blonde hair pulled into a ponytail. Smart. Brave. Graceful and understated. Living in a simple tent in an African forest with all those wild apes wandering in and out of camp.

As it turned out, Jane looked just like the young woman whose image Carole had seen on television in California not two years earlier. It was strange: meeting someone for the first time who was already familiar, like an old friend or a relative. The real person was glamorous enough, though. She was young (only a dozen years older than Carole, more or less), but also self-confident, good-looking, married to a sophisticated European aristocrat, and living an exciting life with animals in Africa. Carole could never convince herself that she was capable of being glamorous like that, since she was tall and big, with big legs and a sensitive personality. It was hard not to feel awkward in Jane’s presence.

The two-story house at Limuru was built of stone and covered by a red-clay tile roof. It included a cat named Squink and two German shepherds named Jessica and Rusty. It was graced with a couple of vegetable gardens, an expansive front lawn with flowers, a rear stable large enough to hold four horses, and an eighty-mile view out the front windows. Jane and Hugo slept in a master bedroom upstairs. Carole and Em were given their own rooms at the first floor level: one in the recently built guest wing, the other behind the kitchen at the back of the house.

Her first morning there, Carole was surprised by a six o’clock knock on the door. Outside the door, she discovered a tray with hot tea in a cozied pot along with milk, sugar, and buttered biscuits, which was Carole’s introduction to a tic of civilized Englishness. Jane’s Englishness, in fact, produced not only tea twice daily but also her finely modulated speech and reserved manner, which at first made Carole feel boisterous in the American way, with a little naïveté thrown in for good measure. During a casual conversation that week, as Carole would later remember, she asked Jane what her favorite reading subjects were, and Jane said she had “very catholic interests.” Carole, puzzled, said, “You mean religious?” Jane said, “Oh!” She laughed, then said, “No, it means just kind of widespread or universal.”

Limuru was in the Kenyan highlands, which meant cool evenings. After dinner, they all warmed themselves in front of the fireplace, talking and drinking scotch. Hugo was a Dutchman by birth, a wildlife photographer by profession, and by inclination a raconteur who enjoyed holding forth on the adventures and dangers of life in the wild. In between Hugo’s wonderful and often hilarious stories, they conversed generally about subjects of mutual interest, such as animals, conservation, tourists, and poaching. As Carole also learned during these conversations, Jane and Hugo, along with baby Grub, were now spending much of their time in the East African savannas—the Serengeti and Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania—photographing and researching vultures and various carnivores. The vultures used stones as tools to break open ostrich eggs, which was Jane and Hugo’s new discovery of animal tool-use that would be featured in an upcoming National Geographic article. The research on carnivores was for a book being financed by advance money from a British publishing house. That was Hugo’s project. He had signed a contract to write it and take the photographs.

But they were a family, and all three—including Grub, of course—would be heading out to their work in the savannas, so Carole and Em would have to travel to the chimpanzee reserve on their own. Once they got there, they would not be alone. Jane had established a routine for the chimpanzee observations, and that routine was now managed by trained observers who were supported by a first-rate African staff. Jane and Hugo would drop in whenever they could. Fly down, most likely. They would also keep in touch by radiotelephone and then come to stay for the whole summer. There would be cooked meals, a private place to sleep and bathe, other Americans to keep them company, and enough typing of the daily scientific record to keep all their fingers and thumbs fully occupied. Jane wondered whether the girls were prepared for the isolation, but there was only one way to find out. She mentioned, also, that they should bring two of everything, including clothes and, since both Carole and Em admitted to being nearsighted, prescription glasses.

So long talks of romantic adventures and legendary places, of vultures and hyenas and chimpanzees, of impractical visions and practical necessities enlivened the evenings in Limuru. During the day, Hugo would drive off to Nairobi to shop and attend to other chores in preparation for the next photographic expedition, while Em and Carole visited with Jane and the baby and endeavored to make themselves both agreeable and useful.

One afternoon, Jane handed Carole the baby, saying, “Can you take him? I need to sleep.” Carole took Grub out into the warm sunlight and bee-kissed flowers of the front yard, where he was fine for about two hours. Then he began to whimper. Carole tried to cheer him up. She bounced him, lifted him up and down. He laughed for a moment, cheered up, but started whimpering again, which was followed by crying. Carole thought Jane could hear them through an open bedroom window, and finally, when she could no longer do anything else, she took Grub back inside, carried him up the stairs, and knocked on Jane’s door. Jane said, “Oh, bring him in. I think he just wants me. He’s hungry.”

That was that, but Carole also knew she was being evaluated, and she felt she had, in handling baby Grub that day, passed part of the test. Indeed, as Jane confirmed by the end of their visit, both Carole and Em were accepted. They would be given the chance to work as volunteer typists at the reserve during a three-month trial period.

• • •

On November 14, 1967, therefore, Carole and Em packed their bags—Carole pressing into the middle of hers the last of her marijuana stash, which was ten rolled joints—and were flown in a small plane south. They passed out of the big city and suburbs and moved over miles and miles of dry savanna, with hard waves of heat rising up unevenly from the flat, dry earth and making the flight bumpy, before at last dropping down at the town of Tabora, in Tanzania. They spent the night in a rundown hotel waiting for the next day’s evening train headed west.

That train tumbled through the night and brought them, on the morning of November 16, to the end of the line, which was the town of Kigoma on the edge of Lake Tanganyika. They stepped into a daylight so fierce it made Carole reel, and they were greeted by two young white people, Americans both, who introduced themselves as Patti Moehlman and Tim Ransom. They were from the reserve. She had a Texas drawl and straight blond hair. He had a restrained manner and unrestrained dark hair and beard. Carole soon learned that he was from California, or at least had been a student at Berkeley, in California, and she liked his sweet smile, as well as the bushy dark beard and long hair, the beaded necklace he wore, and the beaded belt. Carole had seen that sort of beadwork in Nairobi, sold as a Maasai design, but perhaps it was better to imagine American Indians. It was a romantic style, in any case, and she understood it that way.

Kigoma was sleepy, dusty, and hot, with the train station down by the harbor and, running up from the harbor, a single paved street lined with small shops and one or two rough hotels on either side. Patti and Tim had planned their weekly supply trip to coincide with the arrival of the train, and there was still shopping to do. Once that was finished, they hauled everything—including a week’s worth of food and other supplies—down to the harbor and climbed into the Pink Lady, which was a sixteen-and-a-half-foot white fiberglass Boston Whaler with a forty-horsepower outboard. Tim started the engine, and soon they were speeding out of the harbor and slicing a curve to the right and onto the open lake, heading north and following a scalloped shore.

Lake Tanganyika was as clear as glass yet soft, too, as if the glass were coolly molten. You could see right down into the water, far down, until the clarity turned into a pristine blue before slipping into a shadowy blue obscurity. Looking to the left, miles to the west on the far side of the lake, Carole could make out the distant green hills of the Congo, which rose and rolled back inland in waves, merging as they did into a faint haze and turning from green to blue to gray.

The sun pasted itself on bright and hot, but the heat was drawn away by the wind and a cooling spray of water. Sitting in the boat, Carole was not thinking so much as feeling: about how life was serious and how her three months in an African game reserve would draw her closer to the core purpose of her life. The nearby shore on her right was slashed with red erosion scars and marked by villages and rectangular patches of cultivation. After a time, the villages and cultivated patches stopped; and then the boat passed a narrow, jutting peninsula, a headland, and Patti shouted over the sound of the engine that they had just passed the southern boundary of the reserve. The brown hills turned to green, and instead of hot, barren, and sometimes eroding land, there was cool air and dark vegetation.

After another hour or so the engine was cut, and the boat crunched onto a pebble beach. Three Africans appeared and helped drag in the boat and unload the supplies. Then the four of them picked up their personal luggage; passed through a brief zone of fishy stink; and slipped into the shade of forest, a sizzle of insects, and the rank scent of moist earth and organic decay.

2.

The next morning began as a speckled rectangle of light seeping into a room. Carole, raised from sleep by rustlings and whisperings—and seeing Patti at the door—got up, threw on her clothes, grabbed a quick breakfast (toast with margarine and jam, instant Nescafé), then left the cabin to join Patti outside for the first shift. Shift. It sounded like factory work, an assembly line.

It was chilly and wet outside, drizzly and gray and not yet dawn, and Carole paused to take it all in: the tree-studded grassy meadow and two cabins, both made from bolted-together aluminum panels fixed on top of concrete slabs, the bigger one about fifteen by thirty feet, the smaller one the same width and half the length. Both cabins opened to the air and light through wire-mesh windows—no glass—and were protected from the weather by gabled roofs darkly insulated with a thick grass thatch held in place with chicken wire.

The bigger cabin, where Carole and Em had slept, was called Pan Palace. Aside from the large central workroom with chairs and two long tables with two typewriters on top, Pan Palace had a small bedroom to the left and another small room on the right that served as a minor kitchen where people could make coffee or tea and prepare their individual breakfasts in the morning. This kitchen contained a table, two chairs, a gas-bottle two-burner hotplate, and a kerosene-powered refrigerator.

The smaller cabin, called Lawick Lodge, consisted of a single room and served as the directors’ office when Jane and Hugo were there, a storage depot for all duplicate records, and a retreat when the presence of too many chimps and baboons outside required it. Lawick Lodge also contained general supplies and a mimeograph machine for spitting out hand-drawn maps and other documents.

Then there were the boxes: about forty steel boxes embedded in the earth with concrete and scattered around on the ground like forty treasure chests, which was what they were, having been discreetly filled the previous night with chimp treasure. Bananas. The boxes were locked shut. The latches, Patti explained, could be opened remotely by pressing buttons on four panels inside Lawick Lodge. Battery-powered. Couple of car batteries. The juice running along buried wires. Very clever, very smart, but then you had to be smart to outsmart chimps. They went into Lawick Lodge, and Patti showed Carole how the banana boxes worked. Patti looked out through the open, mesh-covered window. She pressed a couple of buttons, and Carole heard the click of latches remotely withdrawn. The boxes were fixed in ways that allowed gravity to do the rest. Lids dropped open, exposing the treasure inside. It was a way, Patti explained, to keep the chimps coming into camp but still under control. No person was allowed to handle bananas in front of a chimp. That way, the chimps, who were far stronger than most people could imagine, wouldn’t learn to associate bananas directly with people and, therefore, would not on a bad day kidnap someone.

The two of them went back outside into the continuing drizzle and waited: Carole standing next to the old steel oil drum on the front lip (the veranda, Patti called it) of the concrete slab for Pan Palace, Patti standing higher on the grassy slope, her tape recorder in a leather case strapped on her shoulder, microphone in hand.

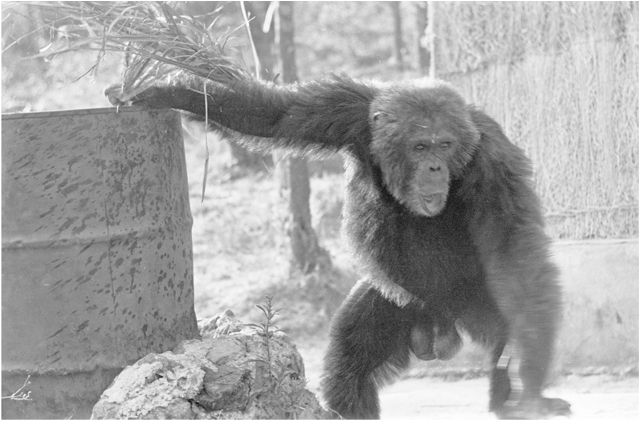

A chimp appeared from out of the forest, the dark shape emerging from the deeper darkness and moving quickly and silently on all fours, galloping like a quiet horse into the clearing. More shapes emerged, appearing as if from another dimension in the oneiric shadows, from behind trees, from inside bushes and thickets, growing larger and becoming fuller and more real in the quiet, trickling morning. They were quick, and although Carole saw that she was taller than any of the chimps, especially when they were down on all fours, the chimps were still bulky and thick-limbed and, in truth, frightening. Especially the big males, who often, with raised hair on their arms and backs bulking them up like Olympic weight lifters, came racing, galloping, careening in, screaming and sometimes throwing rocks and branches. It was mostly display, Patti said. Typical male stuff you see anywhere, chimps or humans. Big ol’ country boys coming into town and showing off, making a big fuss, announcing themselves, showing what big strong hulking macho men they were.

The chimps, Carole saw, were not beautiful, noble, or romantic. In fact, and being entirely honest with herself about it, she thought the chimps were ugly. They looked squashed and degraded. They had short squat legs. Arms long and muscular like a person’s legs. Those huge and ridiculously dangling balls on the males! God! And the puffy pink pudenda of the females. Ugh! So big-mouthed, so explosive, so noisy: grunting, hooting, whimpering, screaming. Carole was thrilled to be there in a real African wilderness, but she really wished that the chimpanzees were lions.

The chimps had come into camp thinking bananas!—and it was Patti’s job, speaking into the tape-recorder mic, to identify who was there and who was not, who was friendly with whom, who was good and who bad, who sick and who healthy, and to describe the comings and goings and interactions of everyone. Carole listened to Patti’s steady commentary. She was like a baseball announcer on the radio, one with a mild Texas drawl giving a dutiful play-by-play description of the game: Mike works up a pant-hoot, displays down north slope. He attacks Flo and Flint. Flo, screaming, carries Flint up a tree, and Mike runs back up the hill and beats on the oil drum. Worzle works up a pant-hoot, runs off into a tree west of camp. Sophie and Sorema arrive from northeast. Leakey and Hugo come in from the east. Flo and Flint now in a tree grooming. Pepe comes from the southwest, sees Mike, begins to pant-hoot and shriek, gives a fear face, goes up and puts a hand on Mike’s shoulder, and Mike begins to groom him.

To Carole, they all looked the same, except for the obvious differences between male and female, young and old. They were just big, scrambling, hairy lumps. Hairy and scary. The males at least. The females, not so much. Carole did her best to stay out of the way. She stood next to the oil drum on the concrete slab, the veranda of Pan Palace, out of the line of action. When Patti told her to, she would duck inside the door and watch through the open window. Yes, sometimes they could be frightening, those big apes, and after she had been outside for only two hours, she was hit, accidentally to be sure, by a stone thrown randomly by one of the males showing off. She wasn’t hurt. And she was lucky that Patti, another time, shoved her out of the way as one of the males came hurtling down a path in her direction. It was dangerous out there, Carole saw, but she also thought that the danger could be good. If you lived with it, adapted to it, became part of it, then you wouldn’t need to live in fear of it. You would face it and begin to see that you’re stronger because of it.

She also discovered, that first morning, another side to the chimps. A male youngster—Patti called him Flint and said he was one of Flo’s children (whoever Flo was)—came right up to Carole and began hitting her on the legs. He wanted to play, and then, after she didn’t respond to the invitation, Carole watched in amazement as little Flint began playing with one of the grizzled old males; together they tumbled and wrestled, both of them laughing as they raced about in a playful mock fight. Laughing! Carole never knew chimps could laugh, but there it was: the breathy, voiceless ah-ah-ah-ah-ah of a person laughing so hard he’s about to pee his pants. They didn’t vocalize much, so it sounded like someone sawing wood.

During that first day, Carole spent much of her time sitting inside Pan Palace alongside Em, both of them in the workroom pounding at the typewriters, transcribing the observation tapes, using both hands to type and one foot to press a pedal that could stop and start the tape. But she was still learning, and Patti kept her outside a lot of the time as well, so that she could learn about the chimps, and when she did that she hardly noticed the time passing. She was fascinated. Maybe twenty chimps showed up that day. Patti said there were about thirty-five regular visitors, but they didn’t all come every day.

Carole and Em type away inside Pan Palace, while Pepe, Charlie, and Hugo groom in the doorway.

A couple of chimps sat on the veranda and gazed at Carole, but mostly they concentrated on themselves and went about their business, which was grooming, displaying, hooting, attacking, retreating, reassuring, nursing babies, and—as the latches clicked and the boxes were strategically opened one by one—gorging on bananas. Patti did her best to introduce the chimps. Flo was the old lady, she said, and Mike was the alpha male. Charlie was the pugnacious one. Worzle was the grizzled one with whites in his eyes, like a person. And Olly was the female with the droopy lower lip.

Then there were the baboons, a whole troop of them, maybe fifty, hanging back in the trees and bushes, careful to keep safely away from the dangerous apes but watching and waiting for an opportunity to steal a banana or two or five. The baboons were a kind of monkey, and the young ones were cute and playful, often jumping and splashing in the swaying, cushiony trees the way little monkeys will do. But, all things considered, these were not your standard attractive monkeys. They spent a lot of time walking on the ground. They had monkey-style fingers and thumbs on their hands and feet, but doglike snouts. And the big males had white eyelids. It looked like a bizarre makeup job, as if someone had painted bright white stripes on their eyelids. Big? The adult males were twice as big as the adult females. They were the size of German shepherds, and they had canine teeth that looked like small daggers, maybe three or four times the size of a dog’s canine teeth. The males would lazily close their eyes, and so the exposed eyelids would flash white, like bright semaphores. Then they would yawn, give a long, lingering, wide-open yawn, and instead of looking sleepy they looked vicious, showing off those daggers. The male baboons were another thing to watch out for, another danger, Carole realized. At the very least, she saw, the baboons were an enormous nuisance, upsetting the chimps, getting in the way. They were creeping, crafty, scrappy, snatching, opportunistic thieves.

• • •

People described the main camp—the little meadow in the big forest where the two aluminum cabins stood, where the banana provisioning and all the action took place—as being upstairs. To get downstairs, you walked down a long and twisting trail for a mile, more or less, until you reached the beach. Tim lived in a hut—tin roof, walls of stick and thatch—down at the beach. That was called beach camp.

Halfway along the twisting trail between downstairs and upstairs, between the beach camp below and the main camp above, was ridge camp, where a cooked dinner was served once the day ended. The African staff, meanwhile, lived with their wives and children in their own camp, which was like a small village, located above the beach and a short distance south of Tim’s beach hut. One of their standard jobs was to prepare the evening meal for the researchers and haul it up the trail to the ridge camp. It was a nice place to gather for dinner, in fact: a natural clearing with a panoramic view of the lake.

When it was wet, the researchers ate dinner inside a small pavilion—concrete slab, four poles, corrugated tin on top—at the ridge camp. There was no furniture other than a couple of foam mattresses tossed onto the concrete floor, with a dim, unsteady light provided by a single hissing lantern. When it was dry, they ate dinner outside the pavilion on a concrete patio, sitting on the same mattresses in the light of the same lantern. Nothing fancy. You helped yourself. Found a convenient spot on a mattress. Relaxed. You might be visited quietly by one of the two catlike creatures, a civet and a genet, who hid trembling in the woods there. Emerging from the folds of darkness at dinner time, they expected a tithing from dinner and sometimes tolerated a pat on the head. But they were wild animals, of course, and always ready to bolt.

People chatted with each other. On Carole’s first night, that meant: Tim the baboon man, Patti the chimp lady, Alice Sorem another chimp person with a long braid hung like a brown rope down her back, and Patrick McGinnis with short hair who was yet another chimp person. And Em, of course, who like Carole had just gotten there.

A cool breeze rose up from the lake. The sweat soaking Carole’s shirt dried off. People talked about what they were doing or hoped to do, and because, from the ridge camp, they could look over and across the lake, they watched the sun turn red and settle behind the purple mountains of the Congo. The ridge they were perched on was bathed momentarily in a warm flash of red, and the lake before them turned indigo, then black, while the moon became a pale, distant eggshell floating over a glistening obsidian expanse.

Patti seemed to be a cheerful sort, and Carole liked her, but she also imagined that perhaps Patti’s cheerful manner was not such a good thing. Patti seemed to get irritated more quickly than the others, and she controlled it under a false smile. Carole also thought maybe Patti liked awkward and self-effacing Em better than herself, but that, of course, was a matter of taste. The others—Alice Sorem, Pat McGinnis, Tim Ransom—seemed old-fashioned. Carole was nineteen, and they were all in their twenties. They also were more conventional and had done real academic work at legitimate colleges, rather than mostly nonacademic things at a nonlegitimate noncollege like the Friends World Institute. Or FWI, as she usually called it. Tim was a psychology graduate student from Berkeley. Alice and Patrick had been friends—had dated, briefly—and zoology students together at San Diego State. Alice also had done baboon work at the San Diego Zoo. Everyone had a college degree. They all had practical plans, schedules to enable the rational progress of their lives, and Carole did not. They were regular, normal people, she thought, open and friendly and without any visible neuroses. That, too, made Carole feel different. Such thoughts and observations flitted fitfully in her mind like the insects orbiting the lantern that lit up the last of the dinner, and they temporarily flew out of her mind when Tim the baboon man leaned over and said, in what seemed like an ironic manner: “And how was the first momentous day with the chimps?”

She answered him as directly as she could, but as she would later comment in her journal, her deeper reaction was irritation. She was irritated both by the question and the way it was asked. She wrote, Why does everybody have to ridicule anything valuable and serious? The irritation receded, and she regretted being so quick to judge, understanding that Tim did not really intend to ridicule her. He was just afraid of seeming serious. But then: Why are people like that? Being serious is much more important than being silly all the time.

3.

The rule was this: Any chimpanzee who came into the provisioning area would be identified and observed, and his or her activities would be recorded. All the records were typed, organized, and assembled into what people called General Records. Patti was the senior person in charge of observations and General Records, but she was going to leave in about a week, having finished her time at Gombe. After she left, Patrick McGinnis was next in line. He would be in charge. Then there was Alice Sorem, who had been at Gombe longer than either Pat or Patti, more than a year all told. But once you proved yourself for a year, you were allowed to move on to specialized research, to do your own project, which Alice was now engaged in. She was studying mothers with infants.

So Carole and Em were the two typists for Patti or Patrick, either of whom would be for the next several days in charge of observations—and always backed up by the other. On a long day there could be twelve hours’ worth of chimps. Since the official observer couldn’t leave during that time, Carole or Em had to fix food and carry it out to that person. Food that was uninteresting to the chimps, of course. Not apples or bananas. Scrambled eggs and toast, maybe, and cups of coffee.

The observer, Patti or Patrick, would finish a tape out there, hand it through the open window to Carole or Em inside Pan Palace, where they sat at the typewriters, and get a fresh tape. So they typed a lot, Carole and Em did, and they were also supposed to keep up the big charts that summarized the whole shebang: the operatic scenario of chimp society as it unfolded each day at the station. On the big charts, the chimps’ names were abbreviated—HH for Hugh, HG for Hugo, and so on—and the nature of the behavior was color-coded. One color for aggression, another for play, and so on. But then, when the chimps had finally left for the day, and after the typing and charting were finally finished, they could all relax. Think. Read. Talk. Or catch up on the typing and records.

Soon enough Carole began to learn the routine, but she still was not resigned to having Em along on this big adventure, and the ambiguous nature of their relationship puzzled and rankled her. Maybe she knew Em too well, was too familiar with her habits and quirks: the unkempt hair, the bit lip, the evasive eyes. Maybe she saw Em as competition or an unhappy reminder of the embarrassing Quakers-in-a-Van school they both came from. And in spite of the reasonable voices coming from her better self, Carole was secretly hoping that Em, who was, after all, comparatively small and possibly fragile, would tire of the job and leave, at least by the end of their three-month trial period. Indeed, Em had already privately admitted to Carole that she was terrified of the big male chimps and couldn’t bring herself to stand outside when the males were making their grand displays. So Carole considered that a good sign.

These were not thoughts to be proud of, and one afternoon, as the two of them sat in front of their typewriters inside Pan Palace, Carole decided to try breaking the shell of bad feelings by confessing everything. Perhaps the mortification of making such a confession would exorcise the feelings, and indeed, at the start of their conversation, Carole did feel relieved. But then the calm way in which her former roommate accepted all that anger while expressing earnest claims to understand and not be hurt by it soon made Carole more irritated. The lack of a real response to her petty feelings began to make them even worse, and so she became more emphatic in her assertions. Finally, it was late in the day and Patti suddenly appeared at Pan Palace, suggesting they all head down to the dinner hut at ridge camp. Em jumped at the suggestion, and her quick departure with Patti left Carole alone and feeling humiliated, since it showed that Em had gotten bored by the confession.

• • •

Patti had been living in a hut, an old rondavel down at ridge camp that was close to, but not quite visible from, the dinner pavilion. It was called a rondavel because it resembled a round hut of the South African style, but it was really octagonal and made of bolted-together aluminum pieces. Still, when Patti showed the hut to Carole after dinner that evening, Carole thought it looked sweet. It was big enough to hold a bed, desk, and chair. It had once been used for storage, and people said to watch out for scorpions, but when Carole saw it, she realized she wanted to sleep there. Patti said that as soon she was gone, Carole could move in.

Within the week, Patti was gone, and that’s how Carole wound up sleeping alone in the middle of an African rain forest. It was a thrilling idea, although she stayed awake for a long time on her first night there, writing in her journal and then, after she had turned off the lantern, watching the final pinpricks of fading light dance and scatter, and being frightened by the well of darkness outside. She had grown up in a suburb of Pasadena, California, which was not a wild place, not many wild animals of any significant size, and yet she still knew she loved animals. Whatever the mysterious, original source of that attraction, it had been stimulated when she began reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Ring series, which she loved because of the talking trees and the various creatures and people. She also read King Solomon’s Ring, by Konrad Lorenz. That was a very different sort of book, of course, being nonfiction and science, but Lorenz was still a lot like Tolkien. The book made her feel that animals were not radically different from people, and that you could get to know them and even, possibly, communicate with them in a marvelous way. Had her early life been simpler, she might have followed that emotional interest in a more methodical and traditional fashion.

That first night spent alone in the forest, Carole found the leg-and-wing machinery of insects chirping and grinding and whirring to be a reassuring kind of background noise, but it would be interrupted by erratic bumps and thuds. More disturbing were the silences when the insect machinery paused for no obvious reason. And there were snakes to think about, a stirring tessellation of them weaving in and out of visibility like the evil spirits they probably were: pythons sixteen feet long with folding teeth as big as dogs’ teeth, night adders, burrowing adders, bush adders, puff adders, sand snakes, vine snakes, boomslangs, glossy black-and-white forest cobras, lemon-yellow spitting cobras, and six-foot-long black mambas with coffin-shaped heads. There was a lot to think about, and Carole felt afraid, although once she realized that she could bolt the door from the inside, and did so, she felt less afraid. The fear did not simply evaporate, however, and the next day, when she thought about it, she understood that there really were things to fear. She was afraid of the chimps and afraid of the forest, and yet she longed to go out into it, too. She wanted to be a wilderness person, but she was just a city kid from Pasadena, and now she had become a typist, spending most of each day typing up records inside Pan Palace.

• • •

Once Patti Moehlman left, Patrick McGinnis was in charge. Pat was on the conservative end of the spectrum. He was nice. He was uncomplicated, kind, and responsible, and Carole looked up to him. He knew what he was doing. But he was also conventional. You could see that in way he trimmed his hair and how he dressed. Even his body and facial hair seemed to follow rules, while his handwriting, which was microscopic, told Carole that he kept himself under a very tight regimen.

Meanwhile, Carole spent her time next to Em, the two of them inside Pan Palace and poking away: tap-tap-tap-tap-tap-tap-tap-ding. And yet all the action was happening outside. That’s why when Patrick asked her if she knew how to work a camera, she said, “Yes!” She had taken pictures during her time at FWI, and she had also learned to develop her own photos. And now because of her supposed facility with a camera, Pat said he wanted her to take pictures of the females’ pink bottoms, which included at the center their sexual parts, their vulvae, their pudenda. All the words for the subject seemed unpleasant, Carole thought, and of course there were much uglier words to consider, so maybe bottom was good enough.

Patrick soberly explained that the female chimps’ bottoms changed shape and color in relation to their monthly cycles, with the greatest period of fertility being marked by the greatest swelling and brightest color. Maximum fertility meant maximum visibility, with the females’ rear ends inflating until they resembled big pink pillows and functioned like big pink flags. The flags were being waved at the males, naturally, who all went a bit crazy in response. It was chimp pornography, but the problem for a scientific human watching the chimps and wanting to recognize fertility cycles was to know as precisely as possible which phase a female had reached. They were like phases of the moon. Was she fully swollen? Half swollen? Three-quarters? What did her fully deflated condition look like? The female chimps were individually about as different in that department as individual women were different in, say, hip or bust size. Patrick explained all that, and he said he wanted a photographic record, a simple way to document what the various stages of swelling looked like for each individual female. He handed Carole a Nikon with a split-image focus.

For her, it was an excuse to leave the typing for a while and go outside: following one of the females until she was about ten feet away from a pink bottom, then sighting and focusing and pressing the button. Carole did it with some distaste, imagining what it would be like if an alien from outer space went around taking pictures of human female bottoms, but she was young and glad to learn anything new, and it meant that she was outside with the chimps.

• • •

She was warned about the dangers. You had to show the chimps that they couldn’t dominate you. People were mostly irrelevant to the chimps. They generally treated people like harmless bystanders who were not really there, were mostly invisible nonentities. But the chimps had this amazing strength, while people in comparison were absolute weaklings, just blobs of soft butter. When the chimps did notice people, they could be dangerous, and if they ever learned how weak people really were, realized how easily they could dominate a person, then everyone working there would be less safe. That’s what Patrick said. So you did not want to give the impression of being afraid or weak. Patrick told her that the most dangerous chimp of all was old David Greybeard. Yes, he was Jane’s favorite, and he was actually gentle. But he would wrap his steel fingers around someone’s wrist or arm and not let go, thus taking that person hostage until a ransom in bananas was paid. Pat worried that one of the other chimps would figure out what a successful enterprise kidnapping was and start to do the same. But aside from David Greybeard, Patrick said, the only other ones Carole really needed to worry about were Hugh, Charlie, and Rix. Any of those three males would charge her and maybe slap out casually with a hand and knock her down.

“What do I do?” she asked. He said, “Don’t run away if they charge. You have to stand still and face them.” “But if they hit me?” “You jump sideways at the last minute, and then keep your feet and don’t show them that you’re afraid. Make sure they see that you can stand up to them.”

So Carole knew about that. And during her first couple of weeks, she was periodically able to leave the typewriter and go outside with the camera, photographing pink bottoms. She saw no sign of any of the four males Patrick had warned her about, because they didn’t appear often.

During that time, though, Carole got to know Mike, who did not charge people, even though he would come in making a grand entrance, displaying. There was that big empty oil barrel on the veranda, and Mike would scramble over, pounding across the ground with his feet and knuckled-down hands, maybe dragging a palm frond while galloping on all fours, the hair on his back and shoulders and arms ruffled up like turkey feathers as he reached the veranda. He would swing one of his great arms and slap that oil barrel with an open hand to make an enormous BOOM!!!! Or he would scramble over and hammer on the side of Pan Palace itself—BANG BANG BANG BANG!!!—and the metal building would shake. If it was early in the day and someone was still sleeping inside, it was like being inside a giant metal drum. A good wake-up alarm for the lazy. The late sleeper would drag on her shorts and shirt, get her shoes on, and go out. Patrick would already have started the observations. He was always ready.

Mike displays at the oil barrel in front of Pan Palace.

Then one day Hugh showed up, and of course Carole didn’t recognize him, since she had never seen him before. Patrick was standing on the upper part of the slope, looking over the meadow, and he saw past Carole to the southeast, where some big shadow had just emerged from the forest. He said, “That’s Hugh coming.” Just as Pat said that, Hugh spotted Carole, and his emotions possibly registered some message like: There’s a new human being! It’s time to test! He rose up from a crouch, stood up on his hind legs, and lifted his long arms. Stretched out like that, Hugh was the tallest chimp of the whole crew, and he ran at Carole with his arms up. They looked huge. With his arms up high, he seemed to be about as tall as she was, but he had those enormous muscles.

When she first saw him, Hugh was maybe thirty feet away but picking up speed. He was running directly at Carole. She could see his small black eyes, and they looked like shiny marbles in the head of some malevolent being. She knew she was supposed to stand still, but she just could not stand in the line of fire, so she started to creep sideways. He adjusted and kept running straight at her. There was no doubt he was aiming for her. Patrick yelled, “Don’t move!” And so she stopped and waited for Hugh to get her. Then at the last minute, when she couldn’t hold still any longer, when he was about to get her, she closed her eyes in terror, bent her knees, and jumped up and sideways. She had jumped two or three inches off the ground, but it felt like slow motion, as if she were in a dream and couldn’t move fast enough. She had been sure he was going to get her, that his huge leathery hand was going to grab her face and maybe tear it off or grab her arm and throw her down. That didn’t happen. She landed, opened her eyes, and he was gone. She was amazed. She turned and looked, and he was running up the hill. He had run right past her, and she had passed the test. She was amazed to have passed the test.

That kind of testing continued to happen over the next several days and then weeks, and Carole continued to pass the test. Each time she did, she gained more confidence. At the same time, once Patrick saw she could do it, he let her come outside more often. Em was smaller and slighter and not as athletic as Carole. Em could never get a good setup and a good jump. She was lightly hit once and that made her fearful, and then she ran. She had been intimidated. She began to come out mostly when the smaller and less aggressive chimps were present: the females or the males who didn’t charge people. She preferred not to be out when the action took place. Carole was different. She used to play sports. She was a tall, strong tomboy, and she got a thrill out of being able to deal with the aggressive chimps.

4.

When Patti was still there, Carole had talked to her about trying to follow the chimps out in the forest, studying them away from the camp without the banana feeding. Patti had said, “That’s what I’d do if I were going to stay.”

Soon after her first month had elapsed, Carole asked Patrick: “Is there a chance that I could follow a chimp into the forest?”

He was discouraging. He said it wasn’t possible. He said the chimps wouldn’t like it. Trying to follow them would make you seem like a predator who was stalking them. They’d leave. “They’d just ditch you,” he said.

Carole didn’t know what to think, because she respected Pat, but she kept in mind what Patti had said before she left. Carole liked Patti and admired her courage.

On one of her days off, Carole decided to try it. The mothers caring for babies or dealing with juveniles were usually the slowest, since they had that extra burden, and Carole found a slow group: a mix of mothers, infants, and juveniles. She saw them wander out of camp, and then she followed them until they were just far enough out of camp that she could no longer hear any human voices. They stopped and sat down inside this wonderful little opening, a cave really, inside a thicket. The cave in the thicket reminded Carole of a childhood hideout. Not high enough for her to stand up in, but plenty of room to sit.

She sat down in there with them, and she relaxed completely, forgetting all the comments from Patrick about whether a person could follow the chimps anywhere. Then she realized how magical it was to be sitting there with those animals and to have them so comfortable with her, so trusting that even when she sneezed and made a sudden, awkward movement they weren’t disturbed. They already knew her as a creature they’d seen, albeit faintly, in all kinds of situations, and now she was less faint. She was there. She was real and in their world. She thought, This is wonderful, and it’s so different from being in camp. She really loved it: sitting with that small group in that wonderful hideout, the little secret forest place that was so peaceful.

Carole was by then accustomed to the sometimes frenetic pace of activity in camp. The chimps in camp had become used to her, and she was used to them, too. It was getting easy for her to deal with, say, one of the wildly displaying males. She had learned how to jump out of the way at the last minute, and she was learning to have eyes in the back of her head, to have that high level of alertness during high-pitched social events. It was thrilling. Of course, there were plenty of extended periods of quiet in camp as well, times when the chimps simply relaxed and socialized peacefully with each other, rather in the style of humans gathered at a picnic. But ultimately, what happened in camp was never completely real for Carole.

The chimps coming into camp didn’t care about the people. The chimps came for the bananas; and when they got there, they played out their own social drama and then they left. And the people there—jabbering tersely into tape recorders, typing tappingly inside Pan Palace, sneaking furtively about in order to photograph females’ private parts—were never partners in the chimpanzees’ personal drama, not part of their lives. The people had tricked the chimps into coming into the clearing. Bribed them with bananas, and who could resist? The chimps played the game, but they didn’t care about the creatures who had set it up. The people were faint and pale and mostly irrelevant, part of the scenery and close to invisible: dim figures perceived briefly behind a film of smoke, distorted reflections glimpsed fleetingly in a dark pool. The people were ghosts, actually, sometimes irritating ones to be sure, and sometimes a chimp had to put them in their place: show them who was who and what was what. But they were still ghosts.

Charlie, Faben, Flo, and little Flint relaxing together.

You don’t have sex with a ghost. You don’t groom a ghost, not really. You don’t seriously punch or pummel or punish a ghost when serious punching, pummeling, or punishment might otherwise be called for. You don’t have an actual relationship with a ghost. Carole saw the truth of that, as strange as it might at first have seemed, and she saw that she had always been looking at the chimps from a different plane of perception and understanding. But now, sitting with them in that little bushy cave, she wasn’t. Or so it seemed. And she didn’t have to argue in her mind with Patrick about following them or not following them. She didn’t have to worry about being ditched because here she was. Here she was! The chimps scratched itches on themselves, under their arms, behind their legs. The juveniles played. The mothers held their babies. At first they avoided looking at Carole, and then they didn’t. They looked at her from time to time, then they looked away again. Mostly, they acted as if the situation were entirely normal: sitting in the cave with one of the strange ghosts from camp. For Carole, too, the experience felt normal, and wonderfully so. It really touched her, and she found herself thinking, Wow, look at this! I get to be here in this wonderful world with these people I know.

She had begun thinking of chimps as people. They were not people, of course, but they were so like people, and she was visiting their community, becoming part of it. The humans at Gombe were her community in one way, but in another way the chimps were her community, too.

• • •

On another of her days off, Carole followed Pooch. She was a young female who, at the time, had a terrible wound that had been plaguing her for a long while. It was a festering, open sore, and the wound made her less fit. She limped. So Carole thought Pooch would be slow enough to follow, and indeed she was. Pooch was stopping periodically to touch her wound and then sniff her fingers. She then would touch her genitals and sniff her fingers after that. She had not had a sexual swelling for as long as she had had the wound, and it seemed to Carole as if the two conditions were related, as if her body was trying to conserve energy and heal the wound.

After about three hours, though, Pooch just slipped away. Carole searched and searched, looking on the far side of Kasekela Stream, crawling through vines and undergrowth until she was scratched and bleeding. It hurt. She was also afraid, worried about putting her hand in the wrong place and touching, or stumbling across, snakes. But her long search for Pooch took her all the way to the Kasekela waterfall and the pool at its base; and when she saw where she was, she threw off her sweaty, dirty, torn clothes and splashed into the deepest part of the cold, limpid, wrinkling water. She dropped into the water and let the waterfall thunder around her ears. She floated naked and face down, dipping her hot, sweaty head under the surface and feeling the cold water reach into her hair and slide against her body. The coldness burned at first, and then it became cool, and she opened herself up to the experience of the water, which turned into feathers. She was feeling touched all over by the elements—the water and the air and sun—touched on her breasts, her thighs, being tickled and caressed, and she luxuriated in the feeling. She flipped over onto her back, laughed out loud, and let the current wash her downstream until she drifted into the shallows.

She stood up and allowed the sun to dry her off and warm her up, and she sat on a warm rock, leaned back, and took in the heat of the sun. She watched butterflies scatter above the banks, and she saw the sunlight skitter brilliantly on the water. As she would recall for her journal that evening, she felt completely and utterly at peace, wanting nothing more than the perfect paradise she had experienced at that moment.

• • •

Carole thought she did considerate things, such as always fixing breakfast for Patrick, from the thorn of guilt rather than the blossom of generosity. She did it because she wouldn’t otherwise be able to enjoy her own breakfast. She would think Patrick was condemning her. Meanwhile, rather than feel angry at Em (who would get up late and fix her own breakfast at a leisurely pace, never offering to fix anything for Pat or Alice or Carole, all three of whom had been working since first light and were exhausted and starving), Carole found herself amazed. How could she do that without feeling crushed by guilt? Em’s lack of guilt was impressive. Really, it was admirable. On the other hand, sometimes it was not.

They all depended upon each other to keep the work going, after all; and when, on one surprisingly clear day in January, Em took the best two hours of real warmth for her own swim, thereby leaving Carole as the single typist upstairs supporting Pat in the chimp observations, she was furious. When Em finally showed up to relieve her, Carole leapt up and began running down the path. She raced down, driving herself, killing herself, ran past the banana storage hut, through the palm tunnel, up the trail to ridge camp and finally up to the door of her hut. Out of breath but still angry, she tore off her sweaty clothes, yanked on her bathing suit, grabbed a mask and snorkel, then ran out and down to the lake.

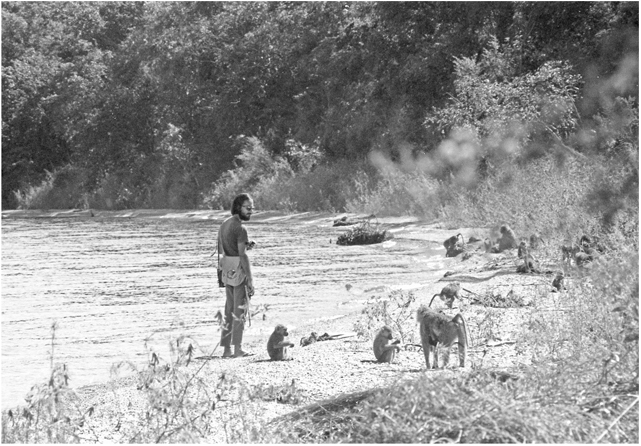

Was it too late? The air was still warm. How was the water? She dove into the clear, clear water, felt the shock of cold turn into a caress of cool, kicked and kicked, and saw that she had entered the pale mansion of the underwater world. The surface wavered silver above while, below, the water gathered into sheets of blue and a hundred tiny fish flicked and darted and joined tightly in a seeking cloud. She was alone, and she felt the water breaking into silver bubbles. She was remembering then forgetting about the people she wished she were closer to, forgetting them and forgetting the pain that people always seemed to bring. She swam parallel to the shore until, after twenty minutes or a half hour, she stopped and stood up, waist deep, to blow out her nose and clear the fog on the mask. The light had changed and an evening breeze had moved in, and it tingled and chilled her skin. She let the mask float on the water, and she recited out loud a few lines from The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock that had insinuated themselves in her mind. The recitation made her feel happy, and it cleared her mind. She walked out of the water and sat on the shore to let the water roll off, and then, when she was chilled, she ran back up to her hut and changed into dry clothes. After drying off and feeling clean and fresh, she walked back down to the beach to visit with Tim the baboon man and Bonnie, his new and newly arrived wife.

Tim and Bonnie at beach camp.

Carole thought Bonnie was lovely. She was short, sharp, opinionated, and she wore muumuus. She had a beautiful face that was sensual and warm. Her lips were full, her eyes brown, her skin tanned a deep brown. Her hair, which was a rich dark chestnut, fell into windblown wisps around her ears. Watching her in the fading light, Carole could see how beautiful Bonnie was.

They talked about Aldous Huxley, and Tim read a passage from Huxley’s book The Doors of Perception. The passage went on and on about the need for a philosophical mystic to maintain perpetual vigilance against the ego. Carole didn’t like Aldous Huxley, even though she considered herself a philosophical mystic, but she was careful to restrain herself, not to say anything negative, because she could see how much Huxley’s words meant to Tim and Bonnie. And after Tim had finished reading, she left them in good spirits, then met up with them again at the ridge camp for dinner.

At the ridge camp dinner pavilion Carole was able to look out over the lake, look far off and see little cells of weather drifting here and there—storms, mostly, moving around like private floating tents with crazed activity inside: frantic twitches of lightning and furious debates between wind and water. Tim and Bonnie had brought up their tape recorder, so everyone listened to music that evening. Carole found the music poignant. When they played the tape of Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, she could only think of the previous summer when she was with her friends, the FWI kids in her group, driving around Switzerland in a blue VW bus for ten days, playing Sergeant Pepper, laughing and loving each other in their lonely way before separating at the end of it all to go on their different journeys. Thinking of those friends made her cry, and she hid the tears, letting her hair fall across her face in a curtain.

But when the music became cheerful and funny, she marked the beat with her fingers and sang the words, thinking how full her life was and how much like a character in a book she was. Somehow she always blamed herself for things—always believed, for example, that she was guilty of her own bad circulation and the unflattering ways in which her flesh adhered to her bones. She tortured herself into thinking she was a glutton because she had big legs. And yet there was no way, except starving herself and hiking ten miles every day (something she had tried and found impossible to maintain) that she could have thin legs. In spite of her body being not perfect, though, it was still a lovely body, and she had a handsome face. She was an individual, she thought, one of those young people who are filled with passion and living on the edge.

5.

Geza’s first hours in Africa were bewildering. The bewilderment could have been partly the fault of his mother, who, laboring under the mistaken impression that her son had taken a sudden leave from his graduate studies in anthropology at Penn State University because he was headed to Africa to work for the famous Dr. Louis Leakey, wondered in a worried maternal way why Dr. Leakey had not informed her son in detail about the arrangements. She enlisted the help of a Teleki relative living in Europe, Lady Listowel, who phoned Dr. Leakey’s office at the Centre for Prehistory and Paleontology in Nairobi two days before Geza was due to arrive and demanded to know what was going on.

Louis Leakey was still in the States at the time, so the long-distance call on Thursday, February 8, was handled by his secretary, Mrs. Crisp, who was already upset from having been swarmed by wild bees on Tuesday. That apiarian attack—twelve bee stings, seven to the head—had led to a ‘peculiar feeling round my heart,’ as the secretary soon wrote to her boss, and her condition was not improved by the call from Lady Listowel, whose sharp, superior tone had seemed simply rude. The voice on the phone had requested to know precisely who was going to meet Mr. Teleki at the airfield when his flight came in on Saturday. And why had no one reserved a hotel room for the young man?

Once she was informed about the impending arrival of this unrecognized individual, Mrs. Crisp did her job as she knew Dr. Leakey would have expected. She arranged for Mr. Teleki to stay at the Ainsworth Hotel for a week. Then she dashed off a letter explaining everything and had it delivered to the airport’s customs officer with instructions to hand it over to the young American upon his arrival. Having done all that to the best of her abilities, Mrs. Crisp intended to rest over the weekend and recuperate from the bee attack. She had a “natural resilience” to such trauma, but the Teleki person’s impending arrival was still an inconvenient and troubling mystery. “How all this muddle occurred,” she wrote to Dr. Leakey, “and where Lady Listowel got the information that you had engaged him for 1 year, I don’t know.”

Meanwhile, Jane and Hugo’s factotum in Nairobi, Mike Richmond, had asked his secretary to book a room for Geza in another hotel, the Devon; and, probably since Geza’s flight was several hours late, neither Richmond nor anyone else met him at the airport. So Geza had no idea where to go or what to do after he stepped off the plane and into a heavy blanket of tropical air. Encumbered by two bulky suitcases and the normal disorientation of long-distance air travel, he spent several hours in the airport, smoking cigarettes and dropping Kenyan shillings into the pay phone while reviewing hotel listings in the phone book, hoping to find out which hotel he had been booked in. At around two o’clock in the morning, he learned it was the Devon. The taxi driver taking him into town spoke only Swahili. The night watchman at the hotel—grizzled, ancient, carrying a stick—also spoke only Swahili. They exchanged a few useless gesticulations in the lobby, after which Geza spied the board behind the check-in desk, retrieved a key, retreated to a room with a number on the door that matched the number on the key, and fell asleep with his clothes on.

The next day, Sunday, he met with some family friends in Nairobi and, in the evening, wrote a short aerogramme to his best friend back in Washington, DC—George Rabchevsky, a graduate student in the geology department headed by Geza’s father—describing first impressions of Kenya and commenting on tourists, safaris, bikinis, and miniskirts. He promised to write again soon and ended with: “Please notify Ruth in case her letter got lost. Mails not too good here.”

On Monday, he went shopping. He bought boots, a canteen, sleeping bag, plastic poncho, two sets of bush shirts and shorts, a rucksack, and twenty-eight rolls of film. The camera store owner was so happy with the big purchase that he had one of his assistants give Geza a ride back to his hotel. There, later that afternoon, a journalist phoned from the offices of the East African Standard, saying that he hoped to get an interview for an article, which he soon did. The article appeared a day later under the heading “A Second Teleki Explores E. Africa.”

“Romantic escapades and noble sacrifices are a familiar part of Europe’s aristocracy during this century,” the piece began, noting that Geza’s great-great-uncle, Count Samuel Teleki, had walked across East Africa during 1878 and 1888, becoming the first European to see Lakes Rudolf and Stephanie, which he named, honoring a couple of royal pals. He left his own name on the Teleki Valley of Mount Kenya and the Teleki Volcano farther north. The article then focused on the family’s present scion, who had just arrived in Kenya and was now coping with time change and sunburn. “The story of Mr. Teleki’s early life reads like a plot from an Eric Ambler thriller,” the journalist wrote, “and he assured me that the reality is grim for someone who had to participate.” The journalist went on to describe the dramatic family escape from Hungary after the war, their arrival and establishment in America, and young Geza’s future plans. Geza’s photograph, pasted in the upper-right-hand corner of the printed article, shows him seated and unsmiling, a bright sun placing his eyes in shadow and emphasizing the lean lines of a handsome face, aquiline nose, and dark mustache. He wears a dark sport coat and tie, and his thick, dark hair has been combed neatly back in a gleaming pompadour. He could pass for a young pop star from the late fifties or middle sixties, one of the Everly brothers, perhaps. But is that uncomfortable grimace caused by lingering fatigue and bright sun, is it a complacent glare, or is it the awkward expression of someone suddenly exposed as the untested descendant of a heroic figure from the past?

Geza had worked hard to grow up normal in America. He had learned to stop thinking in Hungarian, to master American English and baseball, and to become a maturing member of the postwar middle class. Following the example of his father, he refused to make much of the family’s lost fortune, title, and status. That was ancestral baggage. The old stories were interesting, but in the bright and modern days of 1968—the promising new world where he was twenty-four years old and all grown up—little from the family’s past was relevant. On the other hand, a title didn’t mean much without the person behind it, and Geza’s grandfather and father were intelligent, industrious, and bold men who had proved themselves in the blood sport of mid-twentieth-century middle-European politics. As for Count Samuel—the ancestor who walked through East Africa for thousands of miles while his contemporaries in Europe were busy dusting their wigs, and who survived the heat, rains, snakes, whirlwinds, wild animals, hunger, desolation, and cutthroat crosscurrents of intertribal wars and hostilities—he did so because he had the nerve, self-confidence, determination . . . the balls to do it. It took something along those lines to accomplish what he did. Geza could look back at some of his genetic predecessors and wonder if he had something to live up to. It was confusing, if you wasted time thinking about it: Do you ignore or admire your ancestors?

• • •

Early Thursday morning, he took a taxi out to Wilson Airfield, boarded a small, twin-engine plane that flew south, crossed the Rift Valley, and slipped over an outstretched knee of Mount Meru. The pilot then drilled a hole in the clouds and slipped into a miraculous netherworld: a two-thousand-foot-deep, one-hundred-square-mile sinkhole caused, two to three million years previously, by a cataclysmic volcanic explosion. It was Ngorongoro Crater, an ancient pock at the southern end of the Serengeti ecosystem.

Geza looked down and saw, far below, the flash of a pink-edged lake. A scattering of trees that were gathered into wrinkled, dark clumps. The dark vermiculation of a stream or two. A broad stretch of grassland occasionally slashed with stripes of pale brown and dotted by irregular spots and clumps of black. The spots and clumps turned out to be, as the plane spiraled lower, zebras and wildebeests, antelopes, buffalo, and God knew what else. The stripes of pale brown became artificial dirt tracks, of which one in particular, as they continued turning lower and lower, resolved itself into a crude airstrip interrupted by grazing zebras and wildebeests and marked by a flag at one end. The pilot passed low over the airstrip several times to drive away the zebras and wildebeests before dropping down to land.

Geza unbuckled himself and climbed out. The pilot helped unload Geza’s two suitcases and one rucksack, and the pair of them stood there. It was quiet, nothing to replace the ringing roar of flight except the tick tick tick of cooling metal, the whistling of the wind, and the chomping chewing mooing sounds of grazing animals. Geza stood away from the plane to smoke a cigarette. The pilot smoked a cigarette. The wind blew. The animals ate. Then the pilot went through his checklist of wings, struts, tires, fuel levels, so on, and, after reassuring Geza that he would buzz over the van Lawick camp on the way out, he strapped himself in and pressed the button. The twin engines kicked in and started up. The props rattled and spun. The vibrating plane turned about, bounded down the dirt track, and took off.

A half hour passed, with Geza entirely by himself and standing next to his suitcases and rucksack, listening to the wind and the animals, smoking another cigarette. Then he saw a cloud of dust and heard the rumbling of a Land Rover that, as it hove into view, identified its master with bold letters painted on the side: BARON HUGO VAN LAWICK. Why would anybody do that? Geza asked himself. It was ridiculous, this European obsession with titles. And of course, he knew exactly what baron meant. The title happened to mark the lowest spot on the aristocratic totem pole. That was the last thing he would have painted on his own car, not that he would have painted anything else on it. The vehicle came to a stop, and a short, sunbaked, long-haired, unshaven, rather raggedy-looking man stepped out, shook Geza’s hand warmly, and introduced himself as Hugo.

They drove on to the camp, where Geza was introduced to the Baroness Jane van Lawick–Goodall. Or Jane, as Hugo called her then, and as she clearly expected to be called. He was then introduced, in an abbreviated fashion, to Grub, an eleven-month-old baby with yellow hair, grubby face, and a few little white teeth starting to appear. Also in camp were Hugo’s mother, Moeza, come to babysit; an artist friend of the van Lawicks named Bill, come to paint; Moro, a tall and pleasant-seeming African, who was the camp cook; Thomas, who was Moro’s assistant; and Ben, a young American volunteer there to help Hugo with the cameras. Ben came from some kind of itinerant, international Quaker school temporarily headquartered in Nairobi, Hugo explained.

Jane was much as Geza had expected: gracious, barefoot, and slender, wearing khaki shorts and shirt, her blond hair clipped back into a ponytail. He hadn’t imagined, however, that she would be so direct and uncomplicated, and he quickly concluded that they would get along. He liked her. He was also impressed by the camp, which was bigger and better-equipped than he had anticipated: with a wooden cabin and a stick-and-bamboo hut, six green canvas tents, and three vehicles (two of them VW buses belonging to Jane and to Bill the artist, the third being Hugo’s Land Rover) parked to one side. Behind the camp gurgled a meandering stream ambitiously called the Munge River, and standing in the middle of the camp was an enormous fig tree, broad and thick enough to spread a pleasantly subaqueous light over the cabin, the hut, and the tents. The fig tree also hosted a troop of baboons, mostly invisible, who were eating ripe red figs.

The cabin had been modified for the baby’s sake: protected outside against baboon incursions with a wrap of wire fencing, furnished inside with a playpen as well as a scattering of bright toys and a stack of clean diapers. There was also a bed for Jane and Hugo, plus a cupboard, shelves, and a grass mat cast over the stone floor. The tents had been divided between utilitarian and residential. One big tent Jane used as her office, with table, chairs, books and papers, a typewriter. Another big tent was the dining hall and sitting room. Four smaller tents were inhabited by Moeza, Ben, Bill, and now Geza. Bill had extended the veranda of his tent with a tarp, so he had an open place to paint. The two African workers, Moro and his assistant, Thomas, slept in the stick-and-bamboo hut, which also served as a kitchen, with the actual cooking done over an open fire outside.

It was a busy camp, with Jane, Hugo, and the baby often at the center of things. Geza joined Jane and Hugo for lunch in the shade of the open-walled dining tent, sitting back in a canvas chair and gazing lazily over a gorgeous vista that consisted of rolling grassland covered with animals, then a distant glittering lake followed by the rising wall of the crater rim. After a time, Jane retired to the work tent to resume typing, and Hugo, inviting Geza to come along, headed for the Land Rover.

• • •

They spent the better part of the afternoon passing and being passed by hundreds of animals: wildebeests and zebras, gazelles, elands, hyenas, jackals, a few elephants, and the occasional rhino, along with vultures and eagles and dozens of other birds of all kinds. Geza could barely absorb it all. Little more than a week ago he had been staying at his father’s house in a chilled winter in the middle of Washington, DC, concrete and brick all around, cars whizzing back and forth, and now he was enjoying a hot summer within a walled kingdom of animals in the middle of Africa. It was astonishing!

Hugo sat across from him in the front of the Land Rover, regularly stopping to reach back into the open aluminum suitcase on the car floor behind them and pull out, from one of the baize-lined compartments, the right camera. Then he would find the appropriate lens and screw it onto the camera, screw the camera onto a camera mount fixed on the door, and take a picture or several. Both front doors of the car had camera mounts, in fact; and when the situation was good and the light just right, Hugo could drive—thoughtful slow or crazy fast, it didn’t matter—while steering with his left hand, changing gears with the same hand, and holding a camera in his right. Hugo was good at multihanded behavior. It even seemed as if he could hold a camera, steer, shift, smoke a cigarette, and drink coffee simultaneously. Hugo smoked a lot, the old butts piling up and overflowing like a little waterfall from the ashtray, and in the same expression of ambitious excess, he gulped down his coffee, which was instant and spooned out of a can, sweetened with three spoonfuls of sugar.

Hugo had a coiled intensity that Geza soon began to appreciate, since he possessed some of the same nature. Hugo was also a talented and determined photographer, which was another thing Geza appreciated, since he considered himself a serious amateur photographer. Nothing like Hugo, of course. But Geza liked cameras and photography and had brought to Africa his favorite and only camera: an East German 35 mm, single-lens reflex camera with a 55 mm lens. He had bought it secondhand in Washington a year earlier and was eager to apply it to photons in Africa, but now he took pictures sparingly: partly because film and developing were so expensive and partly because he had the sensitivity to imagine that Hugo might not fully appreciate another camera-using person in the car.

Hugo was then concentrating his photographic efforts, he told Geza, on jackals and hyenas. He was doing a book. Photographs and text. He was not much of a writer, he confessed, especially in English, which was his second language, but maybe Jane would help with that. In any case, he wanted this book to be more than pretty pictures. The text would explain the animals, describe them as individuals with names and personalities and life histories, clarify how their societies worked. Fortunately, Hugo had just the previous month gotten out from under the thumb of the National Geographic Society, which for several years had kept him on a retainer. It had been steady work, but Hugo knew he could do better. The trouble with the Geographic Society was that when you worked for them, they owned you. They claimed rights to anything that came out of your camera, which for a professional photographer like Hugo amounted to being owned himself. It was unpleasant, restraining; and since Jane was the National Geographic magazine cover girl, his own subordinate role—merely the photographer, only the husband—was galling. It was hard to be always in your wife’s shadow.

So now, while it was true that he no longer had a steady income, Hugo was free to be his own man. And he still had, for as long as it lasted, a decent advance against royalties given him last summer by his British publisher. The book was going to be called Innocent Killers, and Hugo hoped it would be a big success. The phrase innocent killers meant wild predatory animals—East African carnivores—who killed for their food. They didn’t kill for fun or sport, as people did, so they were in that way “innocent.” The book would feature six carnivores, Hugo imagined—golden jackals and hyenas first, then wild dogs, lions, leopards, and cheetahs. He had already done the photography for a couple of Geographic articles on hyenas and cheetahs. He couldn’t use those photographs, but at least now he knew something about hyenas and lions, which was a good start.

Toward the end of the day, Hugo set up his system for night photography. He fixed to the outside of the car door a board with three flash bulbs powered by a battery and synchronized through electric wires to the shutter of his camera. He attached the wires, flicked a switch that connected to the battery. All he had to do after that, he explained, was find the action, spin the car around in the right direction so that the light would be aimed just so, wait for the precise instant when the action peaked—predator leaping to prey, for example—then press the camera button and, poof, a flash would peel open the dark world to reveal its bright white essence.

It was the wildebeest birthing season, and the hyenas would be out. Hugo hoped to photograph a kill. After the sun and moon traded places, therefore, he and Geza harnessed themselves in, strapped on crash helmets, and drove around without headlights under a creamy round moon, looking for hyenas until they sighted a racing pack of them, ghostly and giggling in their strange hyena way and bounding through the tall grass like a slavering pack of big dogs. Hugo took off, racing right behind the pack, banging and bouncing and swerving across the grasslands at thirty-five miles an hour. But the hyenas gave up the chase after a while, as did, eventually, Hugo and Geza.

• • •

As the days and then weeks of his introductory visit to Ngorongoro passed, Geza eventually came to appreciate above all Hugo’s practical competence. If you were lost at night, stuck in the mud, and threatened by elephants, Hugo would find and extract you. If you were in danger from a pride of lions, he would drive them away, even if it took a day’s effort. He knew what to do, and everyone else in camp would have been helpless without him. True, the Baron painted on the Land Rover was silly, but Geza came to see in him a capable, talented, determined man, a crack photographer who worked hard to photograph animals and who cared about them. From that perspective, then, the episode with Princess Margaret was unfortunate.

It happened late one afternoon while people were relaxing in the dining tent. A pack of Land Rovers raced up, stopped, and people got out. Geza didn’t know who they were at first, but the van Lawicks must have had some warning. Jane, Hugo, and Moeza went over to the Land Rovers immediately, leaving Geza, Bill, and Ben still sitting in the tent. Geza saw an excited gathering next to the cars, and it soon became clear that Princess Margaret had arrived, along with some friends or family members. There were also secret service personnel in the front and back cars of the entourage.