The Sacred and Revolt: Various Logics

In the previous chapter, I discussed an aspect of the organization of sacred space as Freud defined it in Totem and Taboo (1912–1913), recalling how the sons’ murder of the father was repeated during the religious ritual in the form of sacrifice. If you read or reread Freud’s text, you will see that he links the question of the sacred to the double taboo affecting the prehistoric community: on the one hand, the murder of the father; on the other, relations with the mother. Freud thus considers the two points of the oedipal triangle, the two constitutive elements of the oedipal, when he describes the advent and organization of sacred space.

Taint

Let us take a moment to examine the separation from the maternal space, which leads back to the incest prohibition. Seen from this angle, the sacred appears to be a desire for purification.1 But purity can be dangerous, as Bernard-Henri Lévy and others have rightly said.2 This is not a question the media has bothered to develop—it is not a hot topic—and yet it is truly of capital importance. What does one purify through a ritual? And what does one purify oneself of, having understood that all religions are rites of purification? It suffices to think of various systems of ablution: the washing of the feet, confession, and so on. Art and literature are rites as well: recall that Aristotle considered them catharses (in French, purifications).

As I wrote in Powers of Horror, according to a host of anthropologists who studied the question in detail and examined different purification rituals in societies throughout history, purification—eliminating taint—presents an enigma. What is defilement? What is dirty? In certain societies, defilement is identified with substances that must not be eaten. Rules are decreed in the form of food taboos such as those in Judaism, Hinduism, and so on. And if one examines the food taboos or the desires for purification in various religions, it seems at first that purification is recommended or imposed when the border between two elements or two identities has not held and thus these elements or identities blur. For example, the high and the low or the land and the sea must not be mixed; consequently, certain animals that live on land and in the sea or that possess attributes normally associated with land and sea are considered impure. Faced with such food taboos, the modern individual concludes that the impure is that which does not respect boundaries, that which mixes structures and identities. Now, identity must be kept autonomous and structurally pure in order to assure the survival not only of the living but also of the socius. And this corresponds to an archaic demand: “archaic” from the point of view of the history of societies that survive only by differentiating themselves from others, establishing rigorous but guarded links with them. Yet this so-called archaism trips us up more often than we might think, despite advances toward intermingling. I will come back to this.

The second rule, which does not exclude the first but is often concealed by it, ultimately sees the impure as the maternal. Why the maternal? Again, two explanations come to the fore. First, the speaking being’s relationship with maternal space is precisely an “archaic” relationship in which borders are nonexistent or unstable, a relationship of osmosis in which separation, if it is under way, is never absolutely clear. This is the realm of narcissism and the instability of borders between mother and child, in the preoedipal mode of the psyche. Second, if we look at the question in religious terms, we see that the social and symbolic pact that I discussed earlier—brothers rebelling against the father’s authority in order to establish a socius—is a transversal link that is constituted by the evacuation of the maternal: in order to establish the symbolic pact, one has to get rid of the domestic, corporal, maternal container. And even though maternal religions exist, they are always already on a path toward splitting the symbolic being from its psychological and maternal basis. The constitution of the sacred therefore requires separation from the physiological and its framework, the maternal and the carnal, which in fundamentalist monotheism are connoted negatively and sometimes even considered pagan or diabolical. Mystics and artists alike make use of subtle transgressions and skillful mixtures in a magnificent, parallel history.

I will not go further into this debate, although I did want to mention that purification, the elimination of taint, and protection against the maternal are at the heart of the constitution of the sacred and can be read beneath the surface of Totem and Taboo. But the question of the feminine and the maternal is of only secondary interest to Freud, who instead emphasizes the exclusion of the sons and the murder of the father, the abolishing of his tyranny and the constitution of the symbolic pact between the brothers.

An Archaeology of Purity

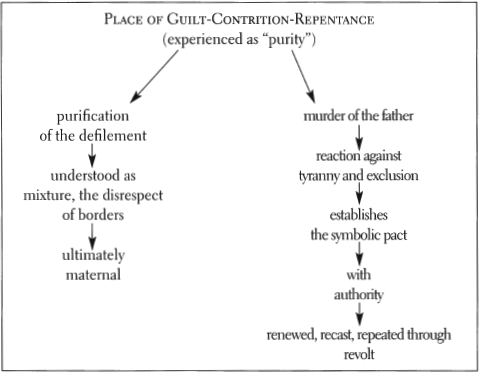

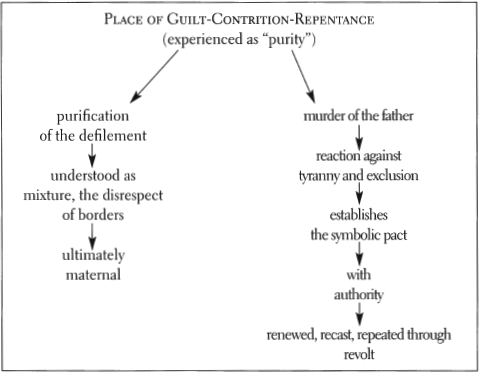

The most virulent aspects of certain religions today that take the form of fundamentalism and other obscurantisms are presented as so many desires for purification. But analysis should not stop there. The tendency toward purification leads insidiously to the demarcation of a place of purity designated by an officiant, a religious member, a place that might be represented by the following schema.

The pure and absolute subject—call him the purifier—defends himself against the maternal from which he is separating through antitaint rituals, while at the same time defending himself against the murder of the father through feelings of guilt, contrition, repentance. Therefore what appears to be purity in the eyes of the religion and the purifiers is only an obsessional surface that conceals a veritable architecture of purity, which I present schematically in figure 2.1.3 It is probably impossible to question the validity of this so-called purity—or to fight the various forms of fundamentalism and violence that appear to be the sorry privilege of this end of the century—by looking exclusively at its surface and not taking into consideration what produces it, namely, the disgust with taint and the consequent contrition, repentance, and guilt that present themselves as qualities of religion but also profoundly constitute the psychical life of the being capable of symbolicity: the speaking being. It is thus important to examine the unconscious thoughts and desires that accompany the murder of the father, the abolished exclusion, and the constitution of the symbolic pact, an examination that will return us to the core of this book’s subject, that is, revolt.

To abolish the feeling of exclusion, to be included at all costs, are the slogans and claims not only of religions but also of totalitarianisms and fundamentalisms. For this, the purifier wants to confront an authority (value or law), to revolt against it while also being included in it. The purifier is a complex subject: he recognizes authority, value, law, but he claims their power must be broadened, rebelling against a restricted power in order to include a greater number of the purified, the “brothers.” This evolution of access to power may be accompanied by contrition (“Alas, I have killed the father, rebelling against him”), and in the ideal hypothesis, certain abuses of power may be renounced as a result (“I” share power with others; “I” therefore renounce certain privileges for the brothers’ benefit), but most often the attraction that authority and law represent imposes on the purifier a paranoid spiral of persecution and revenge. Revolt against exclusion is resolved in the renewal of exclusion at the lower echelons of the social edifice (“I” include myself at the top; “I” exclude those at the bottom).

In the Freudian fable, the father embodies the position of authority, value, and law against which the sons rebel. Their revolt consists in this: they identify with the father and take his place, an integration that constitutes the collective pact, the inclusion forging the link that will be the socius. Thanks to this, the brothers no longer feel excluded but rather have the imaginary certainty of being identified with the power that, prior to the revolt, oppressed them. The benefit Freud observes in this process is one of identification with and inclusion in the law, authority, power. The sense of exclusion that, in our day, is provoked by economic crisis or the condition of foreignness, ethnic or otherwise, may be in some sense cured, or in any case relieved, in a religious space where the individual thinks he can benefit from identification through inclusion within a symbolic community. He moves from a place of national, social, political exclusion to a place of symbolic inclusion; he gains access to a position of power he considered inaccessible until then. The feeling of exclusion is reduced, erased by the symbolic and fantasmatic mise-en-scène of inclusion and identification with a so-called higher power.

Thus, by overemphasizing the purification and “dangerous purity” that religious ties offer, we run the risk of forgetting two things: that the feeling of purification is a benefit after the fact, following repentance, and that the initial libidinal impulse is a violence that involves desiring the father (authority) and taking him (it), in eros and unto death. Violence, repressed in the mind of the believer, remains implied, unconscious, an encoded libido. In fact, if this jouissance were absent, if this pleasure of violence blocked, Freud asserts, the benefit of inclusion would be lessened. And, as I observed in chapter 1, historically if a religion gave its followers the impression that it could not satisfy their need for identity, inclusion, purity—in other words, that it lacked enthusiasm and passion, that it was weakening, declining—then the followers would repeat the act of violence, the sacrifice, either in a strictly ritual form or by acting out. First, rites would be reactivated, the symbolic significance of dogmas reinvigorated, their expansion reinforced, and their influence made to dominate, and then more actual, active measures taken, from persecution to the physical elimination of those outside the religion, indeed, any religion.

I hope I have shown that ideologies that claim to fight religions by assigning them a place of absolute and dangerous purity do not acknowledge the jouissance that the revolt underlying this purity conceals. If you are convinced that revolt is revealed beneath purity, if you agree that “I” can neither include myself nor identify myself without abolishing the authority that oppressed me before and that in this act of abolition-identification lies all the violence of consuming rage and murder, then a crucial question is raised: what modern modes might re-create what was in the not-so-distant past the jouissance of the religious man? Are we capable of this revolt? Not in the actual, concrete form of acting-out, not in the form of violence, inflicted or sustained, but in a new symbolic form? And if we are no longer capable of it, why not? This is an important question, and allow me to emphasize it, for it concerns nothing less than the surpassing of Homo religiosis. Is it possible? Even the question of art and literature is not extraneous to it.

One of the reasons for our incapacity to implement revolt symbolically perhaps resides in the fact that authority, value, and law have become empty, flimsy forms. Here I remind you of advanced democracies governed by a normalizing and pervertible order as an ensemble of structures where power is at once spectacular and vacant, where the legal oscillates between permissiveness and fragility, where scandals and accusations are mises-en-scène organized for the media, and where it is possible, if not easy, to circumvent the law.

As for the wish to be included in the values linked to human dignity, difficulties arise regarding the notion of “rights” and even of “human.” It has been said often enough that human rights represent the last bastion against the loss of values for the subject as defined by the founding principles of the Republic, that is, for the subject who is not the transcendental subject and who does not confuse himself with the code—the defenses—of any of the religions constituting the memory of the increasingly heterogeneous populations that are mixing today in Europe and elsewhere. Now, before our eyes, these values, guaranteed until now by human rights, are dissolving under the pressure of technology and the market, threatened by what jurists call “the patrimonial person,” that is, the human being as an assemblage of organs that are more or less negotiable, that can be transplanted, converted into cash, bequeathed, and the like. Moreover, democracies’ frank abandonment of great political, ethnic, and religious conflicts in favor of military and barbarous powers—as seen in the former Yugoslavia—throws grave discredit on these values that we now call, more and more naturally, so-called values.

Finally, revolt as a producer of purity in our modern world is endangered by an easy—not to say perverse—fit between law and transgression; it is spoiled by constant authorization, if not incentives, made by the law itself, to transgress the law and to be included.

Thus at least two things make revolt in this context problematic. The first has to do with the flimsiness of the prohibition; the second has to do with the fact that the possibility of revolt involves a jouissance that we do not acknowledge, because the very human being that is the locus of it is dispersed into organs and images, and the new maladies of this deliquescent and centerless soul are confined to passivity and complaint.

Priests and the Turbulent Boys

While examining the texts of Mallarmé and Lautréamont, I came across several figures of revolt and its variants or failures in the religious history of Indo-European societies. As suggested by the title of the work in which I developed these questions, Revolution in Poetic Language, revolt was already the central subject.4 The power vacuum and lack of values were not yet issues when I wrote that book in the 1970s; the change no doubt appeared in a more obvious, more drastic, more threatening way after the recent collapse of communism. On a political level, however, the evolution in question has probably been under way since the end of the French Revolution and the development of democracy that followed. But I leave this question open for now to return to the profound logic of the passageways and impasses of the revolt internal to our cultural memory.

In Revolution in Poetic Language, I looked at two figures first examined by Georges Dumézil: on the one hand, the priest, who assumes what Bernard-Henri Lévy calls purity and, I would add, guilt and repentance, as aspects of the religious and cultural pact (I am speaking here of religious culture but perhaps of culture in general as well); on the other hand, what Dumézil calls the “turbulent boy,” that is, the one who represents the jouissance, rupture, displacement, and revolt underlying purity, repentance, and the renewal of the pact.5 The dual logic that structures the living, renewable identity and that the oedipal allows us to glimpse—that is, law, on the one hand; revolt and violence, on the other—seemed divided in the Indo-European pantheon between two distinct figures. The dialectic inherent in the process of revolt, inherent in the constitution of all sacred or social space, was distributed as if the function of purity had been delegated to certain individuals and the function of revolt to others, although one must keep in mind that these two categories converge and one is never possible without the other.

In the Mithraic system of sovereignty of the Indo-European pantheon described by Dumézil, the priest, called flamen or brahman, serves the idealizing part of the religious pact that has reached a form of stability, allowing ties to be formed: inclusion has been achieved, and a temporary equilibrium, assumed by the priest, has been established; the priest enjoys this stability or peace, Mithraism seems to say.

The rebellious sensualist is entirely different. Gandharva, half-horse/ half-man, is the Indian centaur enamored of music, dance, and poetry, arts forbidden to the legislator and priest.6 He heralds an underground economy: the facilitation of revolt and its underlying jouissance. The dual human and animal nature thus revealed seems to indicate, as though by metaphor, ardor and violence, a force difficult for anthropology to contemplate, a “going to the limit,” the metaphor of the horse suggesting the vigor of the drive and a psychical and extrapsychical setting-into-motion that we have difficulty symbolizing.

In Revolution in Poetic Language, I proposed that the function of the horsemen was accounted for in our modern cultures by art and aesthetics—if we accept that sacred space and symbolic space coincide. On the one hand, there is the discourse of the norm and purity, subsuming a social harmony whose symbolic peace the priest celebrates; on the other, there is singing, dancing, painting, the use of words, the exultation of syllables, and the introduction of fantasies in narrative, which first give way to sacred incantation and then are gradually detached from the religious scene in secular literature. This experience, considered “aesthetic” starting with Kant, in fact recaptures the violence and nonsubmission that are an integral part of the social space. Dumézil demonstrates this forcefully: the “turbulent boys” are destructive, but they also promote fertility and joy during feasts. It is during feasts that sacred possibility is unleashed. I say possibility and not purity—that which precedes purity and exceeds it, the jouissance of protest, indeed, of destruction—since the feast is the chance to break down what exists in order to construct a new balance or, more commonly, to return to old habits.

No doubt revolt culture should consider the possibility or impossibility of establishing and elaborating values, pacts, and spaces of purity. But do we have consistent values or purities to propose today? Haven’t the systems that were supposed to protect the last paradisiacal values of a future society where all men would be brothers shown how difficult it is to maintain ideals without exerting the most arbitrary violence? Moreover, shouldn’t we consider this: spaces of purity are secretly sustained by a possibility of expenditure where man brushes up against his animality and where the drive jostles codes in order to try to modify them? When successful, this leads to celebration through dance, which is different from walking, just as poetry is different from language. And religion satisfies the desire for transgression.

The old dialectical model of the law and its transgression in fact remains valid for organizing religious space and the art that is its by-product. If, for example, we ask why certain people return to religion or find refuge in it, we can suppose that it is not only to connect with or attain a pure value: it is also because religion gives each and every person what we might call “warmed-over” fantasies, softened and nonviolent but charged with a certain aggression, which fulfill the obscure desire for pleasurable revolt and, with it, a certain horse-man quality. As for the secular loci where this law/transgression articulation is possible, these are obviously places invested by the arts.

Transgression, Anamnesis, Games

To sum up, Freud’s text poses the following question: if one agrees to accept the constitution of the sacred space that I have outlined, where some take the side of the law (our modern priests) and some rebel against it (our horse-boys), what are the links between the law and the prohibition? Of course, if one considers law obsolete, prohibition weak, and values empty or flimsy, a certain dialectical link between law and transgression is impossible. Many devote themselves to reinvesting purity in values: we do not lack for priests, especially in the media, but where are the horse-boys? The figures of this transgression have been brought to the fore from Hegel to Bataille; the history of the twentieth century is rife with the image of the intrinsically antiestablishment intellectual (you know about erotic literature as subversion; you know that Georges Bataille’s Blue of Noon and some of his other novels illustrate this problematic, which I will not address here).7 Though it remains fascinating and rich in meaning, it is not, in my view, something we can replay in the context of the end of this century. More enraged, and heavily indebted to psychosis, is the rejection of the law and being itself hammered out in the writing of Antonin Artaud. You may also be familiar with the rather smug deployment of perversion as revolt against the new puritan order. Such forms seem relegated to an old space where people still believed in the solidity of the prohibition. On the other hand, if prohibition is obsolete, if values are losing steam, if power is elusive, if the spectacle unfolds relentlessly, if pornography is accepted and diffused everywhere, who can rebel? Against whom, against what? In other words, in this case, it is the law/transgression dialectic that is made problematic and that runs the risk of crystallizing in spaces of repression such as the Islamic world and its fatwas. The decree against the writer Salman Rushdie and the call for his murder for his bold “blasphemy,” illustrating a revolt culture in action that we Westerners willingly support, is not something we have within secular democracy. François Mitterrand is not an ayatollah, and no one in France wants to rebel against the republic. The prohibition/transgression dialectic cannot take the same forms in Islamic societies as in democracies where life is still fairly pleasant, where sexual permissiveness—less prevalent before 1968, one must admit—is considerable, despite the return to conformist tendencies, and where, consequently, eroticism itself is no longer a pretext for revolt. What can one do, then, to rebel in such a situation, when the margin for maneuvering is so reduced?

At this point, I propose a brief return to Freud, where we can detect at least three figures of revolt. First, there is the one just discussed, which might be called ancestral, which constitutes the social as well as sacred link; this no doubt seems very circumscribed and somewhat archaic for democracies today. Another of Freud’s inventions is the notion of analytical space as a time of revolt. I use the term “revolt” here not in the sense of transgression but to describe the process of the analysand’s retrieving his memory and beginning his work of anamnesis with the analyst, whom he refers to as a norm, if only because the analyst is the subject who is supposed to know, embodying the prohibition and its limits. It is in no way normative, conformist, or antipsychiatric to assert that the salutary analysand/analyst configuration inscribes the law at the heart of the analytical adventure. In the Freudian perspective, which already goes beyond the Hegelian dialectic, it seems that what is essential in anamnesis is not the confrontation between prohibition and transgression but rather the movements of repetition, working-through, working-out internal to the free association in transference. It is the course of memory that takes on the Nietzschean vision of an “eternal return” and permits a renewal of the whole subject. Repetition, working-through, working-out are logics that, in appearance only, are less conflictual than transgression, softer forms of the displacement of prohibition as the return of the past and possible renewal of the psychical space.

Consider the analytical situation. A patient goes to an analyst in order to remember his past, his traumas, his feeling of exclusion. A traumatic event has led him to cut himself off from his family, his circle of friends, the symbolic pact: “I” am unable to express myself, “I” am inhibited, “I” am depressed, “I” am marginalized because “I” have this or that sexuality. If the trauma can be understood as a psychical form of exclusion, it will be undone by analysis. This is the sacred space I described earlier, except that the logic of the analytical pact (the transference) is not that of a transgression, or inclusion in a group that is already there, or a taking of power, but a displacement of the traumatism, a progressive, incessant, and perhaps even interminable displacement, as in Freud’s “interminable analysis.” And to what will this displacement lead the analysand? To the possibility of working-out, working-through, and therefore to the construction of a veritable culture where displacement constitutes its source and essence. “I” undertake the narrative; “I” tell of familial or social situations in a way that is stranger and truer each time. “I” am a budding narrator. You may recognize here the Proustian “embodied time,” “the search for lost time.” In the best cases, analysis is an invitation to become the narrator, the novelist, of one’s own story.

Memory put into words and the implication of the drive in these words—which create a style—would be one of the possible variants of revolt culture: again, not in the sense of prohibition/transgression but in the sense of anamnesis as repetition, working-through, working-out or, to replace the Freudian problematic with a Proustian one more accessible to students of literature, “the search for lost time” through narrative enunciation. Which leads me to think that in our civilization—given the impasses of religious forms of revolt as well as conflictual or dialectical political forms of revolt (prohibition/transgression)—psychoanalysis, on the one hand, and a certain literature, on the other, perhaps constitute possible instances of revolt culture. Provided we understand the word “revolt” as it is etymologically accepted: as return, displacement, plasticity of the proper, movement toward the infinite and the indefinite, as I discussed in the first chapter.

A third and final configuration will appear when I speak of the style and thought of Aragon, Sartre, and Barthes, that of the combinatory or the game as possible instances of revolt. Here, again, it is not a question of the confrontation between prohibition and transgression, of these dated dialectical forms, though they are still possible in certain contexts, but of topologies, spatial configurations that are more supple and probably more appropriate to this situation whose difficulty I continue to underscore: how does the patrimonial person that each of us risks becoming confront a power vacuum, armed for discourse with only a remote control? In other words, how, in our societies of the spectacle, does one revolt in the absence of real political power?

Throughout this book, I will try to clarify the two logics of revolt I have just described. But first I would like to explain why I did not refer to Mauss and potlatch when I evoked the necessity for jouissance and violence in revolt.

There are a number of things I have not made reference to, but I could have talked about Mauss, who I deal with rather extensively in Revolution in Poetic Language. It would be equally possible, in discussing the pure and the impure, to cite Mary Douglas’s work on the maternal element in the ambiguous figures of defilement. Still other anthropological models could be summoned to echo what I am saying about revolt as sacred space and its realization today. Keep in mind that they take at least two forms: some plunge into fundamentalism, others into nihilism and despair (“Nothing can be done”). How can one revolt when one is an ensemble of organs? And against whom?

The Permanence of the Divine and/or the Immanence of Language

Before going on to Aragon, Sartre, and Barthes, in the next few chapters I will introduce a few aspects of Freudian thought that strike me as important for a better understanding of the place of prohibition and jouissance, as well as the relations between them: in other words, various positions relating to the links that are not necessarily figures of transgression. I will try to analyze the profound logic of what constitutes this “higher side of man,” as Freud wrote, which is nothing other than the intimate associate of the symbolic link with which, against which, and in which men and women revolt: language.

In this examination of Freudian models of language, notions of power and prohibition refer to the paternal figure, the murder of the father, and the institution of the symbolic prohibition. For all human beings, the instance of the paternal function, the function of authority, is given in an immanent manner in our aptitude for language. In other words, language is an immanent god, unless you would prefer to think of God as a metaphorical extrapolation of immanence. The secular belief—whose foundations we are still seeking, which must neither be too reductive nor too lethal—might be described as this: with language, we will be better able to think about the meaning of a statement such as “God is within us.” If God is within us, it is because we are speaking beings. And it is worth looking at grammar and all the decorative appearances of language, as well as the place of language in the human being’s constitution, autonomy, and relationship with others and with his own body, while taking into account all the parameters that Freudian thought sets in motion and that prevent this thought from being linguistic thought, even though it deals with language.

So if I speak of Freudian models of language, it is to situate what seems to me to be the central position of language in Freud, a place that Lacan had the good sense to underscore. This approach to Freud however may have been too crudely or even mistakenly interpreted; Lacan’s reading started to head toward what he himself called “linguisterie,” a structural approach to language that reduced the signifying functioning of human beings to a rudimentary linguistic schema. This is not at all the case with Freud. As a chronological reading of his texts shows, there are at least three models of language in Freud. These three models, which may at first appear far removed from the problematic of revolt, will allow us to define the imbrication of language in a more complex dynamic that includes both the drive and sacrifice and to address the social link, and the place of literature within it, in another way.