Oedipus Again; or, Phallic Monism

The Conscious/Unconscious versus Knowledge

Before going on to Oedipus, I will conclude my remarks on the three models of language in Freud by responding to a question concerning the link that may be established in the solitude of analytical treatment.

A great analyst, Michel de M’Uzan, asked in his seminar one day: what is the analyst’s organ? The brain? The unconscious? The erogenous zones? Analysts no doubt use all these as well as personality, history, rhetoric, culture, and politics. Consequently, we also use our capacity for revolt as I am trying to define it here. Solitude then becomes an open solitude, and a link is possible between the experiences of those who are attempting to speak.

Now I will return to free association, which provided Freud with the complex model of language on which he based his experiment. Why free association? Why the narrative? This, at bottom, is what interests us as literary scholars. What are the stories that Freud asked his patients to tell? Stories full of gaps, silences, awkwardness—in a way, novels deprived of an audience.

The free association Freud bequeaths us as an essential tool of analysis is not the language sign, the language sentence, but the narrative. To associate is to recount, to develop a narrative activated by drives and sensations, in which phylogenesis is implicated. Moreover, this narrative is bordered by acts— which are unrepresentable in the sense that their intensity destabilizes language—as well as by the feminine, which we have seen obscured, absorbed, and resorbed in the pact among the brothers. Finally, this narrative is tuned in to being, the being of monumental history that Freud intuited through phylogenesis. Narrative, drives, sensations, acts, the feminine in being: Freud invites us to see all these in the free associations of patients. The analyst is led to see sexual difference situated in being; this being evokes something along the lines of the sacred but is dissociated neither from the cosmos nor monumental history nor, for that matter, from the history of the species or the history of the world. The analyst tries to understand the act, in particular the sexual act, by receiving words, bearers of sensations and drives well beyond the signifier-signified system. In addition, he keeps himself alert to the aura beyond language and even to the extrapsychical, which modifies the codes of language by introducing disturbances, lapses, ellipses, silences, rhetorical figures, and, indeed, different myths for both sexes.

We are no longer in the realm of psychology and even less in that of psychiatry: the serene signifiance opens the analyst’s listening to being, certainly, but to a curiously altered being. Our memory, awakened by the narrative sexed in transference, indeed constitutes an unconscious Other (Lacan capitalized it) that inhabits us. We are at the heart of an unsettling strangeness here, and at the same time this memory, however outrageous, is invested by the narrative that restores it to us, that submits it to the domination of the conscious, that deciphers in language and addresses an Other.

This is a major stumbling block for cognitivist theories, which cannot conceive the Other except as an addressee, a double of “myself” and, as such, knowable insofar as identical to “myself.” Now, the history of philosophy—particularly, Descartes, Husserl, and Heidegger—teaches us that there is a logical obligation (“I think, therefore I am”) whereby my relationship to others implies a relationship of being to being and not of knowledge to knowledge. This means that, insofar as the other is himself, “I” cannot know him as such but only think of him in his own being, in his being as an other. If “I” try to think of him, I make the wager that since he is not me, he is different from me, he exists differently than me. “I” therefore make a wager of otherness, a wager in the Pascalian sense, the validity of which nothing can prove to me and which is absolute transcendence. Sartre, as I will show, put this brilliantly in Being and Nothingness: in order to accede to the other, to absolute immanence, “we must ask absolute immanence to throw us into absolute transcendence.”1 The immanence where I am deep within myself (“I” love myself, “I” hate myself, “I” accept myself or kill myself: basically, “I” contemplate myself) is only possible in relation to an other; this has been said often enough. What is more difficult is to think that this other exists differently from me, that he is not simply a mirror image of myself; it is up to me to convince myself that there is an other whose being is radically “not me.” People have managed to do it, in a way, insofar as they have imagined an other who goes beyond them and who is not them, whom they have placed above them and who reigns over the world.

The Freudian revolution proposes that this absolute transcendence is quite simply what makes us speak by making us other-beings, which implies that, far from resembling others, being is always continuously other. This is Freud’s post- or anti-Cartesian wager: an ego addresses another ego, of course, but in fact it is a subject (“I,” who thinks and is) addressing another subject in being. The other is of being, the other is not me, the other is also a being but in another way from me. And it is because the other is a being other than me that I am not simply me but also a subject and that the being that bears us is plural, altered. This is what analysis sounds out: not the complacent communication of ego to ego (though this may be necessary when certain egos are in shreds and need urgently to be reconstituted, through psychotherapy, for example) but an altered subject’s relationship to another being. It is a somewhat ascetic practice, perhaps, but it does not exclude exchanges between egos, decentered by the other and brimming with their “own” unconscious otherness.

In the ideal hypothesis, the patient delivers a narrative as a subject addressing another subject, a subject who constructs himself in this narrative relationship to the other subject. This difficulty cannot be reduced to interpsychical dialogue or “intercognition,” for it is matter not of knowledge to knowledge but consciousness to consciousness. In other words: “I” is not a cognitive strategy; “I is another.” “I” transcends its enclosure as a strategy of knowledge, which it also is. When I say that it transcends this cognitive enclosure, it is not merely that “I” is wrought by this other scene of the unconscious that has to do with another logic (drives, primary processes, etc.); it also means that “I” (which is of being) is constituted as such in relation to the other, which I detailed by going over various stages of individuation. The other is not a redoubling of the ego but a complex dynamic that takes us from language to signifiance and being, which, if you follow my reading of Freud, is not appeased in the serenity that Heidegger finds in it but split to begin with, by letting the other-being of the unconscious appear. There is a piling-up of otherness: the addressee is an other-being; “I” is an other-being; these others are altered by contemplating each other. Far from being absolutized as the summit of a pyramid from which the other gazes at me with an implacable and severe eye, the problematic of psychoanalytical alterity opens a space of interlocking alterities. Only this interlocking of alterities can give subjectivity an infinite dimension, a dimension of creativity. For by gaining access to my other-being, I gain access to the other-being of the other, and in this plural decentering I have the chance to put into words-colors-sounds . . . what? Not a strategy of knowledge but a sort of advent of plural and heterogeneous psychical potentialities that make “my” psyche a life in being.

What I have just said rejoins several criticisms previously set forth by Merleau-Ponty concerning a type of psychoanalysis that he saw as mired in “objectivism”:2 the subject’s dependence on the object (mother or father) is reified; even the drive is seen as a fact of the conscious (objectifiable force or objectified representation); the topography of the psychical apparatus leads to a realism of agencies; the analytical process is thought of in terms of identity and law (same/other, law/transgression, as if psychoanalysis were an extension of an existence according to the law where man has been situated from Saint Paul to Nietzsche); we reduce psychoanalysis to a technique; and so on. However, though psychoanalysis does in fact too often objectify and psychologize the analysand and transference itself, it is essential to emphasize the fact that the Freudian discovery opens the path, at the heart of scientific rationality, to a knowledge and to a transformation of the psyche as a life in being, transversal to psychological objectification. Therein lies its most radical revolt.

Having scaled these heights, let us return to the classic Oedipus, which has its own set of difficulties.

Oedipus Revisited: Sophocles and Freud

Has the Oedipus complex today become a commonplace of psychoanalysis? And, as such, does it still merit our attention? Do we still need to talk about it? These questions have often crossed my mind, and I hope to convince readers that returning to Oedipus is not only important but indispensable.

Quite recently, its central place in the debate was confirmed to me during a lecture I gave at the Ecole Nationale des Ponts-et-Chaussées. I thought it worthwhile to discuss Oedipus at some length. A young lady in the audience got up to say: “Madame, why aren’t you talking about the father? I lost my mother when I was very young. My father raised me. The father must always be spoken of. Everything I am, I owe to him.” She was preaching to the converted, perhaps without knowing it: I, too, owe everything I am to the father, in a way, though as an analyst and also as a writer, things are a bit more complicated for me. But a young girl at the Ponts cannot know everything, even if she already knows a lot, and a lot more than a lot of others, and has gotten to the point of stating brusque truths on the father, unrefined truths but truths nonetheless.

The father is never spoken of enough. Of course, in my practice as an analyst, I continually deal with the debt to the father, often expressed as demand or complaint (as during the lecture I just mentioned)—indeed, as protest—and rarely as desire. Yet by relying precisely on this debt toward the father, I will try to speak of other debts, particularly vis-à-vis the “dark continent,” the maternal continent. For now, however, I will attempt to introduce you to Oedipus, because Freud poses the question of the father using the complex of the same name.

Oedipus Rex

The earliest Freudian reference to Oedipus occurs in a letter to Fliess on October 15, 1897: “I have found, in my own case too, falling in love with the mother and jealousy of the father, and I now regard it as a universal event of early childhood. . . . If that is so, we can understand the riveting power of Oedipus Rex.”3 The Greek myth was able to capture a compulsion that everyone recognizes because everyone feels it. We have all contained within us the seeds of an Oedipus at one point.

There are two Oedipuses, as you know: Oedipus the King and Oedipus at Colonus, which is the story of the blind king who withdraws with his daughter to die at Colonus, in other words, the story of the death of the father. Wanting to leave a testament of his art, Sophocles made Oedipus at Colonus the longest play of the Greek repertory. But Freud was referring to his Oedipus the King, a play that dates from circa 320 B.C. If you reread this text, you will not fail to be struck by what is called the “Greek miracle,” a major aspect of which is bringing forth what we continue to consider our inner life: love, hate, guilt, defilement—the defilement that designates desire as desire for incest and death—without which there is neither happiness nor unhappiness. Given how many years separate us from this text, we can only be impressed by the paradox of this temporality linking such an ancient truth to one so close to us. Oedipus the King was written twenty-three centuries ago, and for almost a century, we continuously return, with Freud, to the topicality of this play. Why this permanence? Is it because it is still alive, we are all constituted this way, and we have simply subjectified or psychologized the same logic that for the Greeks was a fate inflicted by the gods? And what if, at the same time and on the contrary, the constellation of desire, transgression, happiness, and unhappiness that Sophocles put before us were henceforth threatened?

Perhaps Freud revisited Sophocles in order to contemplate this threat. In any case, he recognized that the miracle—of a psyche taking into account desire, law, transgression, defilement, and guilt—had occurred there, there and not in China or India. In Greece we find the origins of, if not the desiring subject—which, as a subject, must await the Judaic interpellation and the Christian incarnation in order to be designated and contemplated—than at least its logic. The logic of the desiring subject is just another side of the logic of the philosophical subject, which we often forget; it is also another side of the subject of science, for the philosophical subject and the subject of science, as Plato (427–347 B.C.) and Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) bequeath them to us, appear around the same time as the tragedy. Obviously, what Sophocles says does not fall from the sky; it is borne by myths and preceded by the epic, incantatory narration of Greek history. But it is through Sophocles’ tragedy that these words are crystallized in the oedipal subject (to get back to the interest of Freud) that is at once tragic, philosophical, and scientific. It is what we are, it is what the best among us are (by “best” I mean those who want to know; those who do not want to know are far more tragic), and it is what Sophocles formulated in Oedipus the King.

Here are two passages from the text that seem to me to define the problematic of the tragic man, this hidden side of the desiring man, also revealed to be clever and knowing. You remember that Oedipus killed his father at a crossroads in the shape of the Greek gamma (τ). Note that it is at this crossroads that Sophocles contemplated the division, the bifurcation between desire and murder. Note also that starting from there he describes to us in less geometric terms what will follow:

Now I am found to be

a sinner and a son of sinners. [The being of the subject is thus posited: “I am Oedipus,” desiring subject, subject of science and philosophical subject; think of all these facets hidden in what follows.] Crossroads, [the desire and the crime]

and hidden glade, oak and the narrow way

at the crossroads, that drank my father’s blood

offered you by my hands, do you remember

still what I did as you looked on, and what

I did when I came here? O marriage, marriage!

you bred me and again when you had bred

bred children of your child [Here the theme of incest is announced.] and showed to men

brides, wives and mothers and the foulest deeds

that can be in this world of ours.

Come—it’s unfit to say what is unfit

to do.—I beg of you in God’s name hide me

somewhere outside your country, yes, or kill me,

or throw me into the sea, to be forever

out of your sight. Approach and deign to touch me

for all my wretchedness [Note the chain: happiness, unhappiness, guilt.], and do not fear.

No man but I can bear my evil doom. [He excludes himself from our community yet invites us to identify with his exclusion.]4

The Chorus concludes, “Count no mortal happy till / he has passed the final limit of his life secure from pain” (2:76). Note the emphasis on the pain inherent in the human trajectory and thus the unhappiness beneath the appearance of happiness.

Here then is what so deeply affected Freud when he exhumed Oedipus the King in 1895–1896 and spoke of it in a letter to his friend Fliess in 1897. He also summarized and explicated the story of Oedipus in The Interpretation of Dreams (1900). What interested him was precisely what Oedipus says in the passage I have just quoted. “Like Oedipus,” Freud comments, “we live in ignorance of the desires that offend morality, the desires that nature has forced upon us and after their unveiling we may well prefer to avert our gaze from the scenes of our childhood. . . . There is an unmistakable reference to the fact that the Oedipus legend had its source in dream-material of immemorial antiquity, the content of which was the painful disturbance of the child’s relations to its parents caused by the first impulses of sexuality.”5 “We live,” “we may well prefer,” “our childhood”: based not only on the emotion that Sophocles’ text incites in him and his own observations about himself—his own history, his personal relations with his father and his own children—but also on the stories of patients, Freud uses the Oedipus complex to interpret his reading and his thought.

The question is not whether the Greeks did or did not experience the Oedipus complex. A number of anthropologists and Hellenists have taken Freud to task, arguing that differences separate contemporary society and mentality from that of the ancient Greeks. This is a pointless quarrel. The analyst that Freud is in the midst of becoming finds in the logic of the tragic text the elements he rediscovers internalized/hidden/dreamed in the contemporary psychical experience. In the ins and outs of finding, thought work is produced: the psychoanalytical interpretation, the invention of the novelty that is psychoanalysis. Consequently, psychoanalysis is not tragedy, and Freud does not say the truth of Sophocles. The concept of Oedipus on which Freud worked after 1897 and that he developed in particular in Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905) did not appear until 1910 (thus relatively late) in the first of his “Contributions to the Psychology of Love.”6 Only twenty-six years after his letter to Fliess did Freud formulate the theory definitively, in “The Infantile Genital Organization” (1923) and “The Dissolution of the Oedipus Complex” (1924).

In “The Dissolution of the Oedipus Complex,” Freud emphasizes what he calls “the central place” of this complex. “To an ever increasing extent the Oedipus complex [i.e., the incestuous desire for the mother and the desire to murder the father] reveals its importance as the central phenomenon of the sexual period of early childhood [i.e., the Oedipus complex organizes the sexual period of early childhood]. After that, its dissolution takes place [this is the latency period]; it succumbs to repression, as we say, and is followed by the latency period.”7 For now, note that Freud emphasizes the central place of the Oedipus complex as an organizer of the psychical life of early childhood.

In “The Infantile Genital Organization,” Freud takes up the theses he already formulated in 1905 in Three Essays. But he modifies his concepts and gives them their final, definitive form, with the libidinal stages—oral, anal, and phallic—that he will not alter. Enumerating these stages he takes care to specify that what he calls “genital organization,” after the oral, anal, and phallic stages, is contemporaneous with and a correlative of the blossoming of the Oedipus complex. (Please be sure to remember that this is a matter of infantile genital organization, to be distinguished from that of the adult.)

What is this infantile genital organization characterized by? By the primacy accorded to the penis, by both sexes. At the same time, Freud admits unreservedly that homosexual and heterosexual object choices, even if they are specified later, are manifested in childhood. Here one can observe three postulates of the Freudian conception of the organization of psychical life: Oedipus, phallic organization (the primacy of the penis), and the castration complex, because the penis in question will be thought of as threatened, especially since it is missing in women.

These ideas, which we see explicated in their definitive form in “The Infantile Genital Organization,” had already been advanced by Freud earlier. Elements of them are present in texts such as “Little Hans” (1909) or “The Wolf Man” (1918), where Freud emphasizes the importance of the penis in his patients’ psychical life and symptoms.8 Later, he continues to maintain the primacy of the male sexual organ. In 1923 he asserts it for the boy as well as the girl, and this is where a number of major challenges arise, spurred by feminism, as you might suspect. I will examine this debate in my discussion of feminine sexuality, but let us start with the boy’s point of view, as Freud explains it, and consider the primacy of the penis, or the phallus, in the boy’s sexuality.

The Primacy of the Penis

Why is the penis the narcissistically invested organ? Because it is visible. (Lacan will valorize a variant of visibility with the “mirror stage,” as I have mentioned.) Representation, as a subsequent psychical capacity, allows one to displace the narcissistic image of the face or any other object of need linked to the maternal presence, onto the eroticized visible thing that is the male sexual organ. Visible, then, and, in addition, eroticized. Why? Because of the erection observed, undergone, or experienced. Finally, the penis is an organ that is detached, in the dual sense of the word in French [se détacher, to stand out, to come loose.—Trans.]. Its tumescence/detumescence induces the threat of deprivation in the little boy, confirmed by the absence of the organ in the little girl, and provides the basis for the fantasy of castration. Starting with this latent absence, the penis can become the representative of other ordeals of separation and lack experienced earlier by the subject.

What other events are organized around the detachable character of the penis? Birth, oral deprivation, and anal separation. The penis ceases to be a physiological organ in order to become a phallus in the psychical experience, “the signifier of the lack,” to use Lacanian terminology, because it may be lacking and because it subsumes other lacks already experienced. To this we must add that the signifier of the lack is the paradigm of the signifier itself, of all that signifies. The penis as phallus becomes, so to speak, the symbol of the signifier and the symbolic capacity.

I will discuss the copresence of eroticism in symbolization later; for now, it suffices to locate the link between Freud’s and Lacan’s reading of this moment in infantile genital organization. The investment of the penis is an investment of all that may be lacking and, starting from that, of all lack as paradigm of the signifiable and the signifier: corporal lack but also, in the field of representation, the thought that represents what is lacking.

Phallic Monism

A second question in the analytic theory surrounding Oedipus concerns “phallic monism,” the notion that every human being unconsciously imagines every other human being to possess a penis. The theory of phallic monism supposes an ignorance of the vagina for both sexes. I will come back to this, but for now let me observe that this ignorance occurs differently in men and women. The theory of phallic monism implies not only that the subject of both sexes is unaware of the existence of a sexual organ other than the penis but also that, correlatively, the absence of the penis, or even castration, is considered a sort of “eye for an eye” punishment against the man or the woman: this punishment is inflicted on the man to punish him and on the woman at the outset, because she is not equipped with this “signifier” at birth.

The question then becomes who is responsible for the punishment, having deprived one sex (the female) of this organ and having the capacity to remove it from the other sex (the male). It is the father, as you may have guessed, who is fantasmatically responsible, who executes this punishment for both sexes. This is the theory of phallic monism; I am only summing up the doxa. I will add that it is a fantasy; at no moment does Freud say that this is what must be thought or what is definitively thought by the human being (although his prehistoric fable supposes that such a punishment might have taken place and, like the father’s appropriation of the women, might have provoked the sons’ revolt against this tyrant).

This fantasmatic organization depends on infantile genital organization. And I underscore this last idea, which has not, I think, been sufficiently acknowledged. Read “The Infantile Genital Organization,” which posits the primacy of the phallus, and you will see that its author specifies that this concerns the development of the child and does not in any way coincide with adult genital organization: “The main characteristic of this ‘infantile genital organization’ is its difference from the definitive genital organization of the adult. This consists in the fact that, for both sexes, only one genital, namely the male one, comes into account. What is present, therefore, is not a primacy of genitals but a primacy of the phallus.”9 Freud makes a clear distinction here that his later readers have had a tendency to neglect: he emphasizes the fact that it is a matter of a phallic organization localized at a certain moment in the subject’s history, which endures as an unconscious fantasy but is not at all the optimal outcome of adult human sexuality. The optimal outcome would be the recognition of both sexes and relations between them. When one speaks of the primacy of the phallus, therefore, one must not lose sight of the fact that it is, I repeat, a matter of a fantasy linked to infantile genital sexuality. If some remain fixed there, it is their structure, but it is not the path Freud envisages in the development of the human psyche. This stage, these fantasmatic unconscious contents, are repressed in the adult, and Freud does not in any way identify phallic monism thus defined with completed adult sexuality, the advent of which he assumes and that is perhaps somewhat of a utopia. Perhaps none of us ever really accedes to this supposed genitality where we recognize our sexual difference and can have relations with beings of different sexes. Perhaps this is another utopic fantasy, indispensable to psychoanalytical theory this time, but rarely if ever attained by real subjects. Let us nevertheless continue to interpret the Freudian idea of a phallic phase as an organizing structure in no way exclusive of adult genitality. A fundamental organizing structure, certainly, but not definitive in psychosexual development.

To sum up these two texts, the Oedipus complex is a fantasmatic organization, essentially unconscious, because repressed, that organizes psychical life and supposes the primacy of the phallus insofar as the phallus is, on the one hand, a narcissistically and erotically invested organ and, on the other, the signifier of the lack, which makes it suited for identification with the symbolic order itself.

The inner workings of classical Freudian theory raise several questions: Is the Oedipus complex universal? Is it the same for the boy and the girl? Are there reversible oedipal stages that would imply homosexuality and heterosexuality?

The universality of the complex is in fact the universality of the triangular relationship that Freud maintains for all civilizations. “Triangular relationship” describes the child-father-mother link, with the father occupying the summit of the triangle, though the relationship may have variations. The role of the father, for example, may be occupied by a maternal uncle in matrilineal societies or, indeed, by a woman, hence the various configurations of Oedipus; but one never observes its nonexistence. The proof of this universality is the incest theory. Lévi-Strauss (whose reticence toward psychoanalysis you are no doubt aware of) nevertheless maintained the principal of the incest prohibition as the organizer of all societies. Now, what does this rule of the incest ban suppose? The recognition of sexual difference; the institution of marriage in various forms with—always—a contract between the two sexes; and, finally, the attribution of the child to the mother and the father, that is, the recognition of generational difference. Many commentators have been content to emphasize the fact that the Oedipus complex implies sexual difference, but we should remember that it also posits generational difference, marked in particular by initiation rites at puberty. The incest ban establishes not one but two differences: that of the sexes and that of generations. The structuring ban prohibits the maternal object and at the same time relations with another age group. Consequently, its perverse transgressions are manifested as much by the refusal of the other sex as by the abolition of generational difference.

It is often asked: Isn’t incest for the man the mother-son relationship and for the woman the father-daughter relationship? Let us look at this.

If the Oedipus complex is a universal structure defining every subject (whether the subject is biologically a man or woman does not matter as long as he/she becomes a subject), incest characterizes the relationship with the mother. For all individuals, men or women, “incest” implies the return to the female parent, the mother, and this, I stress, goes for the girl as well as the boy. There is no lack of obscurity in Freud on this point, but keep in mind that primary incest—which one must call radical or structural, a corollary of the phallic desire and the murder of the father—is the sexual desire for the mother, whether this desire emanates from the girl or boy. This follows not only from the fact that the prototype of the subject in Freud is the boy but from an essential fact I am trying to underline here by emphasizing “phallic monism,” namely, that the phallic reference is indispensable for both sexes as soon as they are constituted as subjects of the lack and/or the representation that culminates in the capacity to think. Starting there, the subject (man or woman) carries out a transgressive, tragic act in desiring the mother. (The configurations of this incestuous transgression are different depending on whether one is biologically male or female, but for now the universality is what is important.)

A last particularity of this universal Oedipus complex is that it declines, Freud tells us; it is destined to failure. Have we really contemplated the consequences of this decline for psychical life?

Oedipus and Failure

Though certainly a figure of revolt, the Freudian Oedipus is also one of failure, a failure that most of Freud’s commentators say nothing about, so powerful is our unconscious desire for a transgressive figure that defies the law and breaches taboos. We might know that Sophocles’ Oedipus is a tragedy, for his revolt is paid for with condemnation and severe punishment; we might read in Freud and observe in anyone that the genital oedipal impulse at the age of five ends in renouncement and that of adolescence is elaborated in a change of object. It doesn’t matter. Oedipus remains a hero for the unconscious; we repress the universality and ineluctability of the oedipal failure. That the oedipal object is an object forever lost and sought is important to repeat forcefully, rereading the Freudian formulation:

The early efflorescence of infantile sexual life is doomed to extinction because its wishes are incompatible with reality and with the inadequate stage of development which the child has reached. That efflorescence comes to an end in the most distressing circumstances and to the accompaniment of the most painful feelings. Loss of love and failure leave behind them a permanent injury to self-regard in the form of a narcissistic scar, which in my opinion . . . contributes more than anything to the “sense of inferiority.”10

“In this way the Oedipus complex would go to its destruction from its lack of success, from the effects of its internal impossibility.”11

Why this failure? There are many causes, which we would prefer not to acknowledge. First, the superego in the boy is afraid of castration, in the girl, afraid of losing the mother’s love; then, the premature beings that we are have a regressive need to conserve the identification with the same sex that precedes the Oedipus and assures and protects us; finally and above all, the child, whatever the sex, feels the intergenerational inadequacy between itself and the desired or hated adult, an inadequacy that magnifies its parent at the same time that it sends back a devalorizing image and perception of its own weakness, of its infantile (physical, genital, mental) impotence.

The failure of the Oedipus is probably this intrapsychical condition that accompanies and consolidates the access to the symbolic function: the renunciation of infantile genitality inscribes impossibility at the heart of the psychical apparatus, and it is on this impossibility that an other unfolds, intrinsic to the matrix of meaning, which is precisely the inadequacy of the signified to the signifier and to the referent, what Saussure called “the arbitrariness of the sign.” By relying on the impossibility of Oedipus, the arbitrariness of the sign already acquired during the “depressive position” is developed in thought,12 and the speaking being invests thought as its privileged object, tentatively or brilliantly, as the history of culture and the academy attest. Moreover, the Greek man named Oedipus was himself subjected to the failure of the Oedipus complex, which explains how he learned to speak and to think and finally to become king: he had to renounce his complex with the substitute parents who raised him and to whom he owed everything—or, at least, his conscious being—namely, Polybus and Merope, who took him in as a child and with whom he apparently behaved normally, that is, like you and I, renouncing his genital impulse of the fifth year, at the risk of unleashing “the most distressing” and “painful feelings,” as Freud says.

Here we are at a crossroads that is no less problematic than the one where Oedipus stood in Sophocles’ text. Is the oedipal revolt absolutely necessary at the same time that its failure is necessary? How are we to understand the sense of this impasse? A particular destiny of the human being is in question here, the logic of which the Greek tragedy already illustrates forcefully. By harboring the desire for incest and murder as well as renouncing it, are we on a slope that inevitably leads to renouncing revolt or else to displacing it indefinitely, renewing it, refining it?

Perhaps the amorous link—and with some luck, a love relationship, and maybe even marriage (why not?)—consecrates both the failure of Oedipus (“I” abandon the drive of desire and death for mama/papa in favor of a new love object) and its renewal (this new object often translates my parents’ traits, without being their substitute, and he/she also provides the genital, pregenital, and narcissistic satisfactions that the oedipal desires of long ago should have or could have offered me). The amorous couple thus succeeds at what has been called an “oedipal organization,” a fragile success and one irremediably challenged by oedipal conflict, which is unleashed each time a disappointment or a new object disrupts the equilibrium.

The twofold danger threatening this oedipal revolt, at once indispensable and destined to failure, is all too clear. On the one hand, there is the definitive renunciation. From the ennui of monogamy, which normalizes and ends up extinguishing desire, to the social group, which impresses its constraints, numerous configurations of our socialization emphasize the impossible aspect of our oedipal structuring and doom the revolt to failure. On the other hand, there is the defiance of the man (more rarely the woman) who has never given up, at least in fantasy. Although he accedes to language and thought and thereby is constituted as a subject, the eccentric personality denies the renunciation and the castration that it implies, though these still organize him as the subject of a symbolic pact. Favored, perhaps, by an indulgent mother who, oh so frequently, has reasons to prefer her son to her husband or encouraged in his narcissism by a permissive or even perverse familial or social group, the eccentric subject does not want to know about failure and, not least, about the failure of the Oedipus. All-powerful, megalomaniac, feeling persecuted at the slightest sign of constraint from others who do not allow themselves to be manipulated as faithful intimates do, our “hero” is fixed at the oedipal level and uses it. He appears to be a rebel, for he violently rejects the symbolic pact whose norm wounds his narcissism as well as his impulse for genital—or, rather, anal—control over the incestuous mother. But his defiance keeps him outside the framework, and, starting from this eccentricity—not wanting to know that the impossible exists while at the same time using it—he cannot construct a veritable revolt but only the signs of a depressed or amused but definitively perverse marginality.

Between these two impasses, the path for revolt is narrow, as you might imagine: dealing with failure, keeping one’s head up, taking new paths (eternal displacement, salubrious metonymy), leaving the nest, refashioning the wager of loving/killing over and over with new objects and strange signs: all this makes us autonomous, guilty, and thinking. Happy? In any case, amorous, for the amorous couple realizes the precariousness, as altruistic as it is inevitable, of the oedipal organization (understood at once as oedipal conflict and oedipal failure).

I will try to show that the experience of writing not only transposes or transcribes the amorous event in the body of language but quite often substitutes for it, when it does not surpass it. Writing as realization of the oedipal organization, as recognition of the failure and renewal of revolt: this is perhaps the secret of what we call sublimation.

Structural Oedipus for Both Sexes

In the current evolution, the boy feels a sexual desire for the mother and a desire for death for his rival, the father; inversely, the girl sexually desires the father and feels a jealous hatred toward the mother. Given this reversal, shouldn’t we reserve the term “Oedipus complex” solely for the boy and use another term for the girl: the “Electra complex,” for example, as Jung proposes?

Freud was ferociously opposed to this proposition. As for Lacan—who was brilliant, as you know—he did not bother himself with such minutiae. In a structural perspective, he preserved the universality of Oedipus and the incest prohibition for both sexes. Yet the rigor of this structuralism is still an oversimplification: when Lacan spoke of incest, he did not specify the sex of the subject in question. I will add that the subtle distinctions of “same,” “other,” and “Other” allow one to eliminate the question of the maternal. This is why I prefer Freud’s theses, which, though imprecise and mutable, seem better able to help us understand how biological difference and the symbolic pact establish the Oedipus as a universal structure.

For the most part, controversies concerning Freudian theory and different currents of research in psychoanalysis bear on the question of the female Oedipus and its differences from the male Oedipus. As for Freud, he maintains it is the father who represents the fundamental reference for both sexes: it is the father the child wants to eliminate in order to inscribe himself in the law, and it is the attachment to the mother that the two sexes have to transgress.

Two Sides

I must emphasize, however, that although it is structural, even the Oedipus has two sides, which are described at the outset of Freudian theory. Freud calls them the “direct” or “positive” Oedipus and the “inverted” or “negative” Oedipus, respectively.

The direct or positive Oedipus is the incestuous desire for the parent of the opposite sex: the boy’s desire for the mother, the girl’s desire for the father. I underscore once again the position of the girl who must separate from her mother in order to desire the other sex, whereas the boy’s desire exists within the continuity of his primary desire. But Freud recognizes the structural implications at stake here. For him, the Oedipus complex concerns girls and boys similarly, with specificities for each sex. The boy’s incestuous desire for his mother, to whom he is initially linked by dependency, demand, and need for support, will subsequently be modulated as a desire for women. The girl, on the other hand, must free herself from this initial, exclusive attachment to the mother, which both sexes have: she must free herself from an “inverse” desire for the mother before she can bring her “direct” incestuous desires to bear on the father (and men). This is a notable difference.

For now, let us grant that inscription in the symbolic/phallic law through assimilation of the paternal place is structuring. In order to do this, the boy kills the father and desires the mother; for him, becoming a symbolic subject and becoming a desiring subject are one and the same. The destiny of the girl is completely different. She completes the same trajectory as the boy in order to become a subject—she takes the paternal phallic place, killing Laius and assimilating his attributes—but the heterosexual amorous choice requires that she take an additional course: she must desire the father and detach herself from the mother to whom she was initially linked by need and desire, tenderly and sexually. This second path, which is called a “direct” Oedipus, assures her erotic individuation as a woman who loves men. The first movement, called “inverted” Oedipus (to absorb/kill the father, to desire the mother), assures her structural place as subject. You may note however that in the direct/inverted doublet, only inverted Oedipus determines what is called a homosexual amorous choice, even though the structure itself of this inverted Oedipus (and not its physical realization) conditions the girl’s access to thought and to the symbolic. This leads to questions concerning certain structural aspects of feminine homosexuality. Add to this structural homosexuality the archaic daughter-mother link that normal evolution abandons in favor of the daughter-father erotic choice, a link that will be called a link of primary homosexuality. Thus we have an endemic and ineluctable female homosexuality, subordinated to female heterosexuality, that does not cease to mobilize feminists in a rather dramatic way and, more lucidly, the great literature of remembrance/revolt, such as that of Proust and Albertine.

Precocious and Biphasic

A final remark will define the complexity of the oedipal organization more clearly. Is Oedipus ontogenetic or phylogenetic? In other words, is it inherited from the history of the species or is it constituted solely in the human being? The Oedipus complex appears late in the child’s development: it refers to the genital phase between the ages of three and six. Nevertheless, Freud considers this stage, and consequently this complex, as being established progressively from the beginning of life. Moreover, in his texts on ontogenesis and phylogenesis, particularly Totem and Taboo (1912–1913), he situates the murder of the father in an archaic history of humanity and, even earlier, to the dawn of hominization. The crossing of an ontogenetic causality with a phylogenetic causality has led numerous analytical currents, from Melanie Klein to Lacan, to consider a precocious Oedipus, what Lacanians call “the always-already-there” (le toujours-déjà-là) of Oedipus, well before ages three to six. This “always-already-there” is explained in particular by the precondition of the paternal function and language. I will have occasion to speak of this again, but for now I will outline the classic postulates of Freudian theory.

The Oedipus complex intervenes between the age of three and six, after which the latency period sets in. Then, at puberty, the Oedipus is reactivated by the development of the subject’s genital sexuality, that is, it culminates when biophysiological maturation makes the subject capable of genital sexuality.13 These two occurrences of the Oedipus complex represent what is called the biphasism of human sexuality, which constitutes the definitive organization of the Oedipus, which in fact always accompanies human psychosexuality.

I will add a last word on early Oedipus. Melanie Klein, for example, situates the Oedipus phase much earlier than Freud does. She believes the incestuous desire for the mother and the desire to murder the father can be observed in the second semester of life, starting at six months. There is a schizoparanoid love/hate phase before the age of six months, during which the child both loves and rejects its mother. This phase is followed by the “depressive position,” which I have often commented on. The breast, perceived by the child as the entire human person, is withdrawn; the child loses its mother; a depressive period sets in. Love and attachment, on the one hand, and an aggressive impulse, on the other, which initially converged on the mother’s breast, will now be brought to bear on the two protagonists of the scene, the father and mother. There is a recognition of sexual difference; love is felt toward the mother, aggression toward the father.

Klein goes even further, and her position seems untenable to many: she considers the child’s aggression toward the father as being directed toward the father’s sexual organ in particular, while at the same time the child fantasizes the presence of this organ in the mother’s body. A fantasy of coitus interruptus makes the child aggressive toward both parents, particularly toward the maternal body fantasized as containing a penis. The Kleinian fantasy, which supposes the three familial protagonists to be distinct at the outset, nevertheless refers to a universe of organs and drives that remains dual. Why is there not a third? Because, I think, of the absence of language in the Kleinian model of psychogenesis. The human being, the child Klein speaks of, is an infans in the etymological sense of the word: the child operates with imagos and does not seem to be motivated by the symbolic third that, at the outset and no doubt well before the child’s birth, inscribes its “thirdness” in the mother-baby relationship and favors the development of thought. The paternal penis, which is so present and so incites the child’s aggressivity, remains in Klein a maternal imago, a sort of other maternal breast, maleficent and competitive but not a third. It is here, I think, that Lacan’s decisive contribution is situated, which should be explained because it shows how the place of the third—that is, the father who will be put to death by Oedipus—is the place of the symbolic (not only the symbolic but also the symbolic).

Sexuality-Thought Copresence

I propose a reinterpretation of the set of theories I have presented that remains close to the Freudian text and follows from it. This is my conception of psychoanalysis, and I will attempt to clarify it as a theory not of sexuality exclusively but of the development of thought copresent to sexuality. This is no doubt what characterizes the novelty of the psychoanalytical intervention and what has been disturbing about it since its foundation. Psychoanalysis neither biologizes nor sexualizes the essence of man but emphasizes the copresence of sexuality and thought. It is on this point that cognitivist theories could make an interesting contribution, for they constitute an attempt to construct a theory of thought in relation to biological and sensorial development. But this is also their limitation, for they pretend to do without sexual development.

I have already pointed out that Freudian psychoanalysis was founded on the asymptote between sexuality and language and that this gap between the two was readable in the first observations Freud made concerning hysterics: namely, the excitability of the hysteric, on the one hand, and the incongruence and inadequacy of this excitability with the thought of the other, as well as the absence of a juncture between the two. Having made this observation, Freud appeared to consider that language at once attests to the abyss between the two sides—excitability/thought—and possible passageways. Your excitation does not correspond to your thought; the proof is you cannot say it. Thrown over this abyss, however, is the bridge of language, for through language the two sides of excitability and thought will try to connect. You cannot say this traumatic excitability, but, more exactly, you say it without knowing it, unconsciously. This other scene of the unconscious will take shape in language, which will become the space of another translinguistic representation. It allows the transfer—Freud called it the “transference,” a term he used first to characterize the functioning of the unconscious and then the link to the analyst—from instinctual conflicts to sensible or reasonable behaviors. From then on, the unconscious will provide the model for a transition between excitation stemming from the physiological, on the one hand, and conscious thought, on the other.

From the beginning of the Freudian inquiry into hysteria, psychoanalysis offers itself as a theory of what I call the copresence between sexuality and thought within language; it is neither a theory of sexuality in and of itself nor a biologization of the essence of man, as it is often reproached for being. Though Lacan highlighted this essential characteristic, it was already inscribed in the Freudian approach itself. As for Kleinian theory, even polished and refined, it sets up a silent universe, a wordless dramaturgy of energies and organs. Certain modern avatars of pre-Lacanianism are susceptible to the same criticisms. We forget that the psychogenesis of the child established by Freud is a psychogenesis of capacities of representation or thought, insofar as these capacities are linked to sexual conflicts. Freud, in sum, speaks of the way in which the child’s thought is constituted in relation to his sexual conflicts. What happens? A range of heterogeneous elements is offered to the infans, a diversity of representations is put in place, particularly through the Oedipus; all of this ends in genitality as well as the active exercise of the symbolic function, that is, the mental capacity to speak, to reason, to be creative in language.

What are the stages of the genesis of the symbolic function, stages in which the Oedipus, while exerting an influence from the beginning of human life, occupies a pivotal place, always with the copresence of excitation and mental representation that will work its way to thought? The first is separation from the maternal object. Starting with this separation, Freud speaks of a primary identification with the “father of the individual’s own personal prehistory.” For the child to separate from the mother, a primary identification with this father is produced that is already the inscription of a third, with whom the child is not yet engaged in a struggle to the death. We might wonder to what extent religions celebrate this father with the miracle of the God of Love. Second is the mirror stage, that is, the identification of the self, visible through the gap that separates us from our body and the maternal body. Third comes narcissism, the investment of the ego: “I” love myself, me, “I” love my image, my body. Fourth is the depressive position, namely, the separation from the other and the investment of hallucinatory capacities: “I” hallucinate mama, and “I” invest these representations; “I” no longer invest the breast or the bottle; “I” invest what “I” imagine. This hallucinatory representation functions as a sort of footbridge favoring access to signs and to the linguistic capacity that replaces the earlier symbolic equivalents. We are in the presence of the first sublimation, which becomes intrinsic to the human condition; the investment of signs is translated by a surpassing of the depression, by a jubilation: “I” invest signs; I am happy with the pleasure that signs procure for me. The investment of language therefore necessitates a certain retreat of the libido in relation to the object: “I” do not invest the breast, “I” do not invest mama; “I” invest my own capacity to produce signs. This is the beginning of intellectual pleasure, a moment of extreme importance that continues in the sublimation subjacent to all creative activity, artistic creativity, for example.

After these stages, the oedipal conflict takes place. But the triangular relationship and the appearance of the oedipal agency—preceded by this procession: hallucination, representation, sublimation, and the investment of the sign—are established gradually. The oedipal conflict (incest, the murder of the father, and the trial of castration) includes the subject—already able to sketch out his autonomy, perceive himself as abandoned or separated, identify himself in the mirror, detach himself from his mother—in the signifying chain. The signifying chain is made up of three protagonists, and the subject situates himself in relation to three: “me, me, and me.” He signifies as an “excluded third” demanding his rights and inserting himself into language, law, socialization and thus acceding to thought, in the sense of the capacity to formulate his place not only in society but also and consequently in the transsocial world. It is in the oedipal conflict that the symbolic capacity will, in sum, be measured, and it is here that the question of the father resurfaces, because this symbolic capacity will be referred to him specifically. Until the Oedipus complex, thought was not referred to the father as an obstacle but as a pole of identification: he loves “me” and protects “me” in order to separate “me” from the maternal container. Starting with Oedipus, thought will be referred to the father as the oedipal father, the third, an agency of the law. “I” must identify myself in relation to this law at the same time that “I” must separate myself from it in order to create my own place, the site of my expression: “I” have a place of my own.

This process of integration of the sexuality-thought-language copresence leads the child in the oedipal triangulation to locate—repérer, if you will—the separability of the father, a separability in the sense that the father is different, in the sense that he separates himself from the mother and child. He is a third, he is separated, and at the same time he is separable; he is not only a support, as the father of individual prehistory was, that of primary identification, father love; he may also be threatened: “I” can take his place, “I” can dislodge him, “I” can displace him, “I” can “differ” him, as Derrida says, with this term’s unconscious psychoanalytical implication, the violence of the rejection attending différance. Because of the phallic investment, this separability of the law is referred to the father, who is not only the third but also the bearer of the penis endowed with all the imaginary implications I pointed out earlier.

While language is strongly implicated in the oedipal conflict, the little boy imagines an identification between the strange function he acquires progressively, which is speech, and the gratifying yet threatened oedipal experience, which is penile or phallic pleasure. This pleasure is at once referred to his own body (the real dimension), the father’s body as the bearer of the penis (the imaginary dimension), and the social function the father represents (the symbolic dimension). In other words, during this oedipal experience that characterizes us as human beings, an equivalence is produced between phallic pleasure, on the one hand, and access to language—the function of speech the child acquires—on the other. This speech is a cold abstraction, extraneous to the body-to-body contact with the mother, to the warm dimension of echolalia, rhythms, perceptions, and sensations; extraneous to the sensory, it situates the subject in the frustration of the absence of objects that were once immediately satisfying. Speech is frustration but also compensation, for it is the source of new pleasures and new powers, which are the benefits contributed by the abstract: hallucinations, representations, and thought salvage and refashion what was lost. The complex experience of the access to language that I am describing here, which is consolidated through the Oedipus as a result of the child’s neurophysiological evolution, demonstrates the copresence of thought and pleasure—all the more gratifying in that it is threatened (presence and lack)—that the little boy experiences with his genital organ, which is also his father’s.

In this parallel between the sexual experience and the experience of thought, this transfer, this transference that articulates mental space, our interiority, occurs at a precise moment of the evolution that will be reactivated at puberty. Essential to this is the development of the repressed construction that is the symbolic phallus, a function of the father and language, which remains in our unconscious. Added to this is the imaginary phallus, which is phallic power accompanied by the threat of castration. Finally, there is the real power, that is, the erection, or powerlessness, impotence on the physiological level. Corresponding to these three levels are the surges as well as the disturbances of thought and language.

Presence and Death of the Father

This dynamic of simultaneity between eroticism and symbolism is present from the very start of the speaking being’s life. The different stages of the dual neurological and psychical maturation impose it throughout the subject’s existence. But during the oedipal ordeal, a first coincidence occurs between the investment of the phallus and its lack on the real and imaginary level in the little boy, on the one hand, and the order of language, on the other. The trial of the third (the Oedipus) accommodates not only the coincidence between the phallus and its lack and language but also, and consequently, a coincidence between the speaking-desiring subject and the place of the father as father of the law.

In this complex problematic, what does the term of lack signify? What is lacking? And how is it lacking? The lacking penis is castration. The lacking father is his absence or death. The paradigm that we have just elaborated thus comprises the penile organ (present/absent, powerful/powerless, impotent), the order of language (the real object/the signified through absence/the signifier of this signified), and the place of the father insofar as he is both presence and death. “The father is the dead father and nothing else,” Lacanian theory tells us. This means he only exercises his signifying role of guarantor of authority if he is capable of lacking this authority. How? By being put to death, which is another, more dramatic form of absence. But the father is not “always already” dead “on his own.” He dies by and through the subject, precisely, who must put him to death in order to become a subject. Here we find the logical necessity of the oedipal tragedy mentioned at the beginning. In effect, if the father is always there to block the horizon, if he does not become “dead,” “I” have no chance of inscribing myself in the power that is corporal, penile power but also the symbolic power of language. Male or female, in order to find my place in the sun of the Intelligible and the Other, “I” must kill the father, holder of phallic or symbolic power, and at the same time wage a war against my drives in order to translate them into representations and thereby not only be an instinctual being but also a being who first hallucinates and imagines and finally thinks—with a little luck.

This split, or internal unfolding, that “I” force on myself in order to become a being of thought (although “it” is “always already there,” “I” nevertheless necessary must become, “I” must acquire symbolic capacity, “I” must manifest it, “I” must represent, more and more, and better and better, throughout my evolution) finds its external correlate in the struggle—the revolt—against the paternal agency, in his being put to death, which is, once again, manifested in the tragedy. In order to become “myself,” for the subject to become himself, the death of the father and/or the lacking signifier is necessary. The desire for the mother, an unconscious, incestuous desire, supports and propels this struggle to the death that consolidates access to thought.

There is no signifier that is not lacking, no father who does not become dead: these are the two aspects of the castration fantasy, fantasy because, of course, this is an imaginary construction, which does not at all mean that it is unessential: starting from this fantasy every subject is constructed as such, that is, as desiring and thinking. Perhaps you believe, as some do, that no one is obliged to be a subject, no one is obliged to posit himself as envious of the place of the father, desirous of occupying the place of the father, assuming a law and being put to death oneself, for, of course, if “I” put myself in the place of the father, “I” risk being subjected to the same hazards “I” inflict. The tragedy calls us to occupy this place of death and desire; it is even the condition for becoming a knowing, philosophizing, thinking subject. But are we necessarily forced to submit to this uncomfortable logic? Are we necessarily subjected to this crossroads, this gamma-shaped bifurcation where Oedipus stood? Can’t we slip away and occupy other places in human history: The anti-Oedipus? Or the normalizing and corruptible new world order I described earlier, where we would be neither guilty nor responsible? Wouldn’t this allow us to avoid having to confront the paternal function, to avoid being subjects in the sense I have just described, that is, in the classical sense, meaning the Greek, tragic, knowing, and thinking sense? But then, what would we be? Neither guilty nor responsible: Is that to say free? Or rather mechanized, roboticized, lobotomized, a sorry and embarrassing version of the human?

That said, the phallic issue as the Oedipus presents it to us—and which, once again, is linked to the destiny of the subject in our civilization, even if it is threatened by the hybrid forms I evoked—cannot be the sole issue. Civilizations exist in which the place of speaking beings, while structured in relation to power and law and thus referred to the father, is not thematized as such. These are civilizations in which the subject does not confront the phallus but the void—Taoism, for example—or the maternal. These are religions, “philosophies” in the non-Greek sense of the term, hence the quotation marks, human organizations that emphasize not the ordeal of power but other modulations of the symbolic-sexual copresence.

In this different preoedipal or transoedipal order, articulations of representation are produced that I define as “semiotic” 14 (Piera Aulagnier refers to them as pictograms) and that return above and beyond the oedipal barrier that constitutes the sign, the signifier, and the entire mental organization targeting univocal communication. These earlier elements return in symbolic organization, disturb it, modify it, and constitute highly curious signifying manifestations—for example, the symbolic practices that one finds in societies where writing is not based on the phoneme and the sign in the Western sense of the term but on gesture, calligraphy, and rhythm. In our societies, heirs to Greece, the Bible, and the gospels, the equivalent might be signifying practices that constitute revolt in relation to the law and the univocal signifier—for example, aesthetic practices, artistic practices that redistribute the phallic signifying order by causing the preoedipal register to intervene, with its procession of sensoriality, echolalia, and ambiguous meaning. Whatever these practices and manifestations (it is here that we seek experiences of revolt), it is indispensable to point out the structuring yet traversable role of phallic organization, which can be challenged.

The Freudian tradition has the advantage of having underscored the structuring role of Oedipus and the phallus. But it perhaps has the disadvantage of having done so without indicating forms of modification, transgression, and revolt vis-à-vis this order. In any case, we cannot speak of revolt without redefining the axis against which it is organized and elaborated in the psychical space of the speaking being.

The Phallic Mysteries

Before concluding this chapter, I would like mention several mythological references that are part of the history of religions and concern the importance of the oedipal organization, as well as what we might call its phallic manifestation, a manifestation that in reality is its very essence, because the attack of the paternal figure amounts to an ordeal vis-à-vis the phallus insofar as it is the representative of both the organ and the symbolic function.

The observation was made long ago: all forms of the sacred, all ritual celebrations can be traced back to a phallic cult. It is a controversial observation, although it has been supported by numerous scholars who point to the mysteries of our Greco-Roman world and find equivalent expressions of them in other civilizations, for example, the mysteries of Eleusis, the Orphic mysteries, and the Dionysiac mysteries in Rome. Some of these celebrate social cohesion through a rite involving the veiling and unveiling of the phallus. In his library, Freud had a work by the eighteenth-century anthropologist Richard Knight, A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus and Its Connection with the Mystic Theology of the Ancients, in which the author maintained that the primitive cult of the phallus is at the origin of all myth and thus the basis of every theology and the core of Christianity. I have presented the Freudian version of the Oedipusphallus in an effort to establish the unconscious logic behind this imaginary. Another author, Jacques-Antoine Dulaure, published a work in 1805 entitled Les Divinités génératrices; ou, Le Culte du phallus chez les Anciens et les Modernes. “It would be difficult,” he wrote in regard to the phallic cult, “to imagine a sign that better expressed the signified thing.” A sentence of interest for linguists, isn’t it? I do not know if Lacan was aware of this book, and, needless to say, for this author in 1805, the words “sign” and “signified” have no relationship to the signifier and the signified as we understand them after Saussure. Still, they highlight the fact that in the phallic celebrations the phallus is a signifier, a sign in relation to a signified, this latter being nothing other than the possibility of generation, the genital capacity, the power to procreate, the aptitude for being sexually creative. This creativity is no doubt cosmic, not necessarily the sexual desire of interest to psychoanalysts but an extension of it, which Dulaure explains as the thing signified by a signifier or sign: the phallus.

The binary logic that the phallus symbolizes is contained in the presence/absence dichotomy inherent in the threat of castration, or the referent/ sign dichotomy, or even that of every marked/unmarked signifying articulation. Here the phallus object plays a role of sealing the signifying dichotomy: it organizes the sacred space in which the cult of our capacity to signify is developed. At the unconscious origin of the phallic cult we find the sacralization of this capacity, which perhaps has nothing sacred about it except the signifying aptitude of the human being, his difference in relation to other species, the ability to create meaning.

Given the prevalence of the phallus, it would be interesting to know what other sorts of logic, besides binary logic, the phallus organizes. Perhaps here one could contemplate the semiotic, the preverbal, and various forms of fluid, sensorial organizations: from pictograms to other pre- or translinguistic representations. Researching types of representations or psychical acts, which would not be those of the signifier and language, could have extremely important anthropological implications, as this would concern not only the maternal and the preoedipal but also other forms of the sacred, not the phallic sacred exclusively.

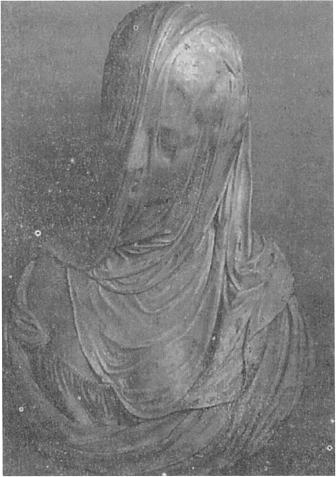

As a sort of conclusion, I would like to comment on a few Italian baroque sculptures: Modesty and Veiled Christ, found in the Sansevero chapel in Naples, and Purity in Venice (see figures 4.1, 4.2, and 4.3). Modesty (1751) and the magnificent Purity are by Antonio Corradini (1668–1752), a sculptor who worked in Venice, Este, and Naples. Veiled Christ is by Giuseppe Sammartino (1720–1793). As you know, not far from Naples, north of Pompeii at the Villa of the Mysteries,15 the initiation rites of the Dionysian mysteries and phallic cults were celebrated with the veiling and unveiling of the phallus. The word “mystery” itself has the Greek root *muo (hidden, closed), from the Sanskrit mukham (mouth, hold, closure), rendered in Slavic languages as muka (pain, mystery). The mysteries were processions, rites that involved both showing and hiding what our anthropological author called the supreme sign, the phallus. This practice is found in humanity’s sacred arena in various configurations that hide and show not only the phallus but all sorts of other desirable objects or objects that become desirable by being veiled/unveiled. Just think of the importance of the veil in temples not exclusively devoted to the phallus but housing other hidden forms, Jewish and Christian places of worship, for example.

It is hard not to be struck by the profusion of veils that dissimulate, as though to accentuate, the sacred figures from the Gospels, which are quite anthropomorphic and no longer phallic: Jesus and Mary, of course, but also allegories such as Modesty, Purity, Prudence, and so on. The baroque sculptor does not present us with phalluses, as did his predecessor, the painter of the Villa of Mysteries, but characters, incarnated forms, bodies. Yet he veils these bodies as the phallus was veiled in Pompeii. All art, all innovation—I will say in passing that the innovation of forms is both an ultimate and user-friendly revolt—is translated by work on the veiling and unveiling of tradition (that celebrating the human figure and, earlier, the phallic cults). The figures are sculpted in marble, covered by veils both marmoreal and gossamer through which we make out the figures perhaps more effectively than if they were bared. The veil expresses the divine presence/nonpresence, an invitation to see the object as it is, though it is hidden. And thus the question of presence and absence is taken up again in a new form.

The theme here is not castration or death but their différance in an economy that is, strictly speaking, infinite, like the multitude of folds of the veiling and unveiling. This secret, or discreet, reference to the phallic mysteries became a source of aesthetic innovation in the eighteenth century; baroque art was constituted, beyond mannerism, in an internal conflict with anthropomorphism. In effect, in the baroque art of two centuries ago, these veiled virtues and this dead, veiled Christ do not merely present us with theological signifieds; in this baroque veiling/unveiling we find beyond the forms themselves a kind of abstract art. For the essence of the virtuosity here involves the possibility of constructing folds that do not represent anything besides representation itself and its possible failure, namely, the cult of the unrepresentable, which is inverted in an apotheosis of the very art of representing, with all its limits.

When the phallus becomes the equivalent of representation and vice versa the questioning of one implies the questioning of the other. To hide/show, to examine what is showable, to veil it, to make the visible appear through that which obscures it, to center attention on the possibility of monstrance itself: this is an inquiry into the roots of phallic meaning and simultaneously into power and the sacred, which are its apotheosis. The baroque sculptor who managed to give a marble veil the aquatic fluidity of transparency in fact situated himself at the heart of the mystery, if it is true that the mystery resides in the emergence and extinction of representation and/or the phallus. There is no phallus this time, but it is displaced in the body, entire and absolute: the body of Christ and those of the allegorical women who conceal themselves by exposing themselves in a subtle displacement, a veritable revolution of thought.

Antonio Corradini and Giuseppe Sammartino seem to me to illustrate perfectly the problematics of presence and absence already contained in an inquiry of representation itself. With them began the modern conviction that culture is a resorption and displacement of the cult: culture will only be the veiling or unveiling, beyond the phallus, of the entire body of representation itself; culture is a representation that unfolds representation. As such, culture is a mystery, though I prefer to say that as a veiling and unveiling it is an exquisite revolt. Perhaps mystery and revolt are the same thing, if you admit the capital place of real presence and its absence, which found and structure our desires as well as the major themes of our civilization. If revolt/transgression is impossible or exhausted today, the baroque sculptor’s exquisite gesture invites us to seek ways to veil/unveil the key values of a culture in crisis and to transmute them.

Veiled Christ by Giuseppe Sammartino, Sansevero chapel, Naples. © Scala.

Modesty by Antonio Corradini, Sansevero chapel, Naples. © Scala.

Purity by Antonio Corradini, Correr Museum, Venice. © Scala.