BORN ON JUNE 14, 1946, little Donald Trump had golden hair, pink cheeks, and a tiny pucker of a mouth. This “blonde and buttery” boy, as a nursery school teacher described him, started life lucky. He had wealthy parents who were strict but loving, and two older sisters and a brother to pave the way. The family’s maid, Emma, made a mean hamburger. Their black chauffeur drove Fred’s two Cadillacs, which had been tricked out with vanity license plates that said FT1 and FT2.

But when Donald’s younger brother, Robert, was born in 1948, disaster struck. Sometime after Robert’s birth, his mother lost her uterus and nearly her life from infections and the surgery that followed. But Fred, the sort of guy who wore a business suit to the beach, didn’t go to pieces. Instead, he powered through the crisis and expected his kids to do the same. He sent Donald’s big sister Maryanne to school with a promise that he’d let her know if anything bad happened.

Donald was just two when he almost lost his mother, too young to understand what was happening, and too young to remember it. But he wasn’t much older than that when he developed a reputation as a menace in school, church, and the neighborhood. He chucked rocks at a neighbor’s baby in a playpen. He pulled hair and blew spitballs and smashed baseball bats in rage. He also couldn’t admit to being wrong, once insisting the wrestler Antonino Rocca was “Rocky Antonino.” And Trump regularly talked back to teachers at school, where he was so often in trouble that his initials, DT, became shorthand for detention.

“He was a little shit,” one of his teachers would remember, years later.

“Surly,” another said.

As an adult, Trump himself claimed he punched a music teacher in the nose.

Despite Donald’s struggles in the classroom, he excelled at recess. In merciless games of dodgeball, he was often the last boy standing. He liked baseball well enough to write a poem about it. His elementary school yearbook published this ditty about his favorite things—winning and the adulation of the crowd:

I like to hear the crowd give cheers, so loud and noisy to my ears. When the score is 5–5, I feel like I could cry. And when they get another run, I feel like I could die. Then the catcher makes an error, not a bit like Yogi Berra. The game is over and we say tomorrow is another day.

Mostly, though, people didn’t cheer for little Donald. And despite Fred’s attempts to teach him discipline and frugality, Donald didn’t seem to be outgrowing his belligerent ways. Fred wasn’t certain what to do. He’d been twelve when his father died. He didn’t have a map for this.

He didn’t have a map for this.

When Donald was thirteen, Fred was fed up. Donald had been caught playing with a switchblade, so Fred sent the boy away to school, hoping the rigor and discipline of New York Military Academy would turn him into a winner.

The New York Military Academy was nothing like Donald’s home. Since he was four, he’d lived in Queens with his family in a twenty-three-room Georgian mansion. Built by Fred, the Trump house was a huge, brick structure set seventeen steps off the street, dressed up in white shutters, with a pillared entryway topped with an iridescent crest. Equipped with an intercom and one of the neighborhood’s first color TVs, the Trump mansion was the fanciest in the upwardly mobile, nearly all-white neighborhood, which Donald’s parents fretted over after an Italian family moved in.

The New York Military Academy, over sixty miles away, was the sort of place parents sometimes sent sons who’d gone off the rails, a place meant to bring them back to their better impulses with discipline and messages like the one emblazoned over the front entrance to the school: “Courageous and gallant men have passed through these portals.”

Sporting a military-style uniform and golden buzz cut, Donald marched off to the 120-acre campus in the Hudson Valley. His new life meant he’d live in barracks, share bathrooms with other boys, and eat institutional spaghetti, meatloaf, and fried leftover meat formed into “mystery mountains.” He’d face inspections of his bed, shoes, and schoolwork.

The freedom that Donald had enjoyed—to ride his bike through the neighborhood shouting obscenities, to sneak away to Manhattan with a pal—was gone. Now he was under the gaze of a World War II veteran named Theodore “Doby” Dobias, a man who’d watched the Italian dictator Mussolini swing from a rope and wasn’t afraid to smack an unruly cadet. If students had lousy grades or stepped out of line, Doby would set them in a boxing ring so they could knock sense into each other.

Initially, Donald didn’t impress Doby.

Initially, Donald didn’t impress Doby.

“We really didn’t care whether he came from Rockefeller Center or whatever,” Dobias later told a reporter from the Washington Post. “He was just another name.”

Another name was exactly what Donald didn’t want to be. He wanted to be the best. He wanted applause. He wanted to bask in the spotlight (or in a pinch, an ultraviolet light he set up in his room to make it feel as if he was tanning at the beach).

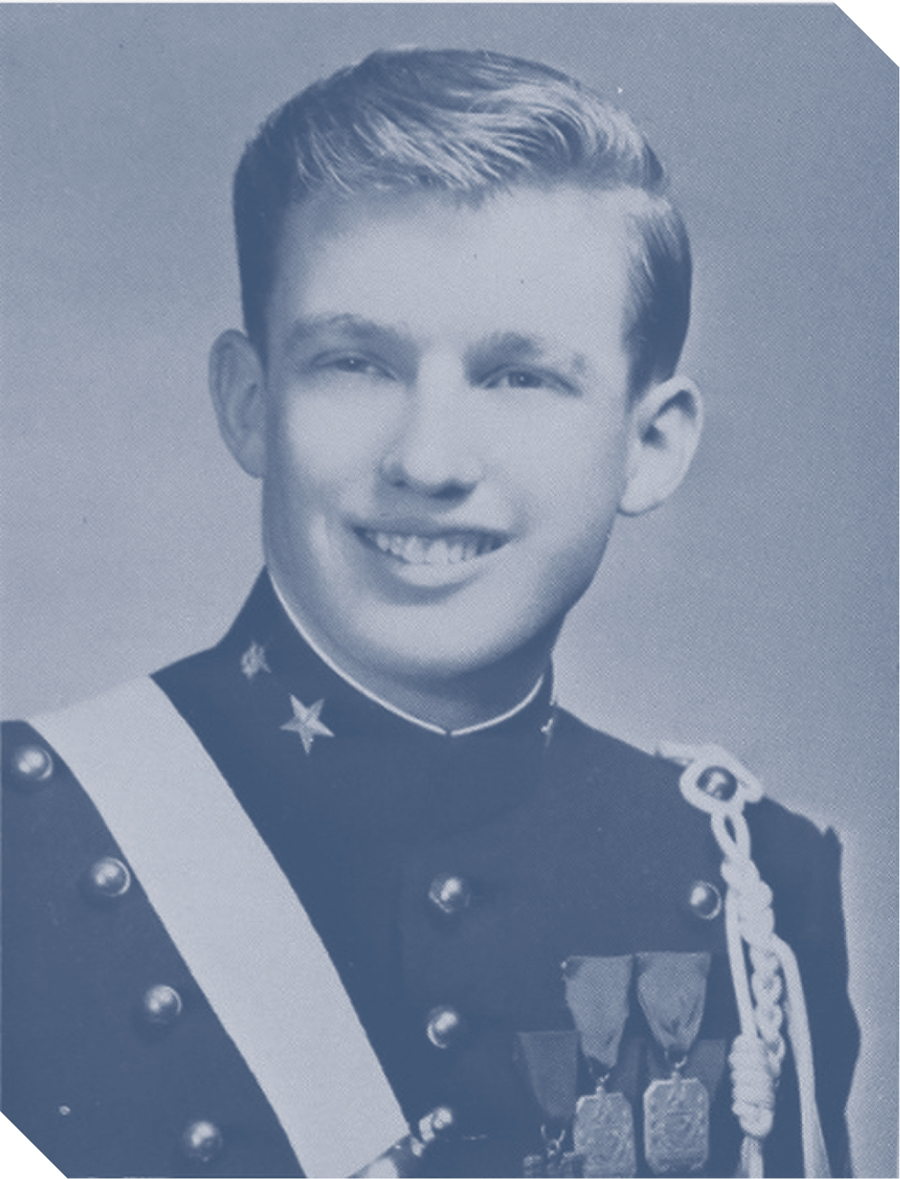

Donald Trump in his New York Military Academy uniform. At NYMA, he won neatness medals and set up a makeshift tanning light in his dorm room. (New York Military Academy)

Even then, “he wanted to be number one,” Dobias told the Post. “He wanted to be noticed. He wanted to be recognized. And he liked compliments.”

Before long, Donald figured out what he needed to do to get the kind of attention that didn’t leave marks. First, though, he had to make sure his dad didn’t come to campus in one of the limousines. Fred Trump tried that once, and Donald put a stop to it. He didn’t want to stand out that way. He did want to stand out in other ways, though, and his first triumphs were a pair of medals he won for neatness.

A roommate, Ted Levine, called him “Mr. Meticulous.” It wasn’t meant as a compliment. The two got along like orange juice and toothpaste. Once when Ted didn’t make his bed, Donald got so mad at him that he ripped the sheets off the mattress and pitched them on the floor. Ted retaliated by chucking a combat boot at Donald and whacking him with a broomstick. When Donald tried to shove Ted out of their second-story window, a pair of cadets broke up the fight, the sort of thing that wasn’t uncommon at the school.

The military academy could be rough. By Donald’s senior year, the superintendent was dismissed over epidemic student hazing. Donald steered clear of that, although he lost his post as captain of the A Company after one of the boys he commanded was reported for hazing a freshman. Donald, who’d spent more time holed up in his room than managing his officers, was moved out of the barracks and into the administrative building. He still had a leadership position, but he didn’t get to oversee any other boys.

During his time in military school, Donald did more than chase neatness medals and indoor UV rays. He excelled at sports, playing varsity baseball, football, and soccer; he was a junior varsity wrestler, and spent three years in a bowling league. He led a Columbus Day parade, served on three dance committees, and joined the Driver Education Club and the Hobby and Model Club (he’d had a large train set at home). During his senior year, he won a captain’s award for baseball as well as a coach’s award for the same sport. Academically, he won two awards as a “proficient” cadet and four awards as an “honor” cadet. But there was at least one way he surpassed his fellow students: His classmates voted him the campus Ladies’ Man.

Through military school, he looked up to his big brother, Freddy, who was handsome and charismatic and knew how to fly planes. Donald kept Freddy’s picture in his dorm room. Freddy would also sometimes take Donald for rides in his Century speedboat during summer breaks. But as much as Donald admired Freddy, his brother was also turning out to be a cautionary tale.

Six years older than Donald, Freddy was expected to take over the family business after his graduation from Lehigh University. (For some reason, elder sister Maryanne wasn’t expected to do so, despite being a graduate of the more prestigious Mount Holyoke.) He went to work for his dad to build a huge development on Coney Island called Trump Village. But Freddy didn’t live up to his father’s expectations. Fred Trump made a point of frugality. He would pick up unused nails at construction sites and reuse them. When Freddy once installed new windows instead of fixing old ones, his dad savaged him. Freddy started drinking heavily. Donald watched and learned. Eventually, Freddy left the company to become a pilot.

Meanwhile, unrest in the world was growing, and boys Donald’s age were being drafted into the military and sent into bloody conflict. These times tested the character of many, and when Donald graduated in 1964, his school yearbook, Shrapnel, told the boys: “Wherever your interests may lead you in this life, let it never be said that you overlooked the essential nature of integration of moral principles with academic training. The countries represented in this graduating class of 1964 look to you to set and to maintain high standards of ethics, of integrity, and of moral and spiritual values. Even though public disclosure of adult corruption comes before us almost daily, you must not yield to it …

“Scholastic achievement and moral principles go together—and … these are only the minimum requirements for a real leader of men.”

Leadership and integrity weren’t abstract questions. The United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War—a conflict between North and South Vietnam over communism—was ramping up, and Donald was of draft age.

He had no desire to fight in Vietnam.

He had no desire to fight in Vietnam. There were a few ways to avoid this duty—principally, by becoming a conscientious objector or getting a medical or educational deferment, something boys from wealthy families found easier to do than their poorer counterparts. As long as a student made academic progress, he could stay in school until he was too old to be drafted. This is why a high percentage of men who went to Vietnam were everything Donald wasn’t: poor, undereducated, blue collar, or African American (unemployment was a factor and black men were particularly vulnerable to that).

Producing movies sounded much more appealing than jungle combat. Donald considered the University of Southern California. But he was accepted at Fordham College at Rose Hill, a Catholic university in the Bronx. He spent two years there, playing competitive squash and taking time on weekends to golf and work with his father, but he otherwise wasn’t a standout, at least beyond his expensive clothes and red sports car.

Donald could afford these things because of a family trust fund. Starting in 1949, Donald and his siblings each took in $12,000 a year—six figures when adjusted for inflation.

Despite having the cash and accessories of a playboy, Donald didn’t drink, smoke, or party—he’d seen what that had done to his older brother. He studied. He dated pretty girls. He worked. And he got his first two student deferments from the military draft.

He had bigger ambitions than Fordham, eventually applying and transferring to the Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania. Freddy knew a guy on the admissions committee, and Penn’s Wharton School of Finance and Commerce had a real estate department, which appealed to Donald. He couldn’t wait to compete with what he perceived as better class students. Once among them, though, he didn’t distinguish himself academically, and one former professor, William T. Kelley, ranked him among his least promising students.

Twice more while at Penn, Donald held off the military draft with student deferments. Two months after he graduated with his BS in economics in 1968, he got a 1-Y medical deferment for bone spurs in his heels, a usually painless condition that is common among athletes who’ve run and jumped a lot. (They’re common among the general population, too; about 38 percent of us have them.)

Because Freddy was working as a pilot, Fred Trump elevated Donald, who’d already been working as his sidekick on trips to Cincinnati, to check up on a 1,200-unit apartment complex called Swifton Village. Fred had snapped up the development in 1964 for $5.6 million because he couldn’t resist the deal. The garden apartment complex had fifty-seven two-story buildings on forty-one acres, and it had cost $10 million to build using government funds in the 1950s. Within a decade it had become such a wreck half the units were empty. (The original builder, like Fred Trump, also was accused of pocketing windfalls.)

With Donald on hand to witness, Fred cracked the whip and brought Swifton Village back into order. Fresh paint, appliances, landscaping, security guards: They were going to make it a decent place to live. And sure enough, new tenants started filling up the rehabilitated place. But the Trumps only wanted a certain type of tenant.

In 1969, a year after Trump graduated from Penn, a prospective tenant named Haywood Cash put in an application. Trump’s rental agent told Cash he didn’t make enough money to live there. Cash—who was black—contacted a civil rights organization with his wife. A representative of the organization, called HOME, used the same income information to rent an apartment, which they then tried to turn over to the Cashes. The Swifton staff erupted, and the general manager called the HOME worker a racist slur before booting her and Cash from the complex.

Had this happened before the Civil Rights Act of 1968, Cash might have been stymied, even though Fred had settled previous discrimination complaints at the Swifton outside of court. The Cashes wanted justice, and the act gave them grounds to file a lawsuit. Over the objections of Donald, who thought his dad had done nothing wrong, Fred Trump offered the Cashes an apartment. The couple also collected the highest amount of damages possible, $1,000 (around $7,000 in 2018 dollars).

When Cincinnati’s real estate fortunes turned a couple years later, the Trumps sold the complex for $6.75 million, a profit for the family and Donald’s first seven-figure deal. It was a big deal, to be sure.

But it wasn’t Manhattan.

But it wasn’t Manhattan. That was the big leagues. That was where Donald wanted to play. And that was where—whatever it took—he intended to win.