“Thanks @piersmorgan! ‘Trump is the most unpredictable, extraordinary, entertaining & massively popular candidate this country has ever seen.’”

—@realDonaldTrump, May 20, 2016

AS 2015 CAME TO AN end and nights grew darker and colder, Trump’s rhetoric followed suit. He pledged to bring back torture, “bomb the shit” out of Islamic terrorists, and kill their families—a war crime. His supporters loved it, though, and he continued to dominate the media and climb in the polls.

He turned calls for torture into performance art at rallies like the one he held just before Thanksgiving in Ohio. Wearing a navy suit and powder-blue tie, Trump feigned weariness with the media.

“This morning, they asked me a question,” he said. “‘Would you approve waterboarding?’”

He repeated himself. “Would I approve waterboarding?”

He repeated himself.

“Would I approve waterboarding?”

He pointed to the cheering crowd, which knew its cue. More cheers erupted.

“Would I approve waterboarding?” he asked once more, before launching into a gruesome and detailed account of what the “other side” allegedly does.

“They chop off our young people’s heads and they put ‘em on a stick,” Trump said. “They build these iron cages, and they’ll put twenty people in them. And they drop them in the ocean for fifteen minutes and pull them up fifteen minutes later.

“Would I approve waterboarding? You bet your ass I would. In a heartbeat.”

The crowd cheered again and waved TRUMP: MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN signs.

But Trump wasn’t finished.

“I would approve more than that,” he said. “Don’t kid yourself, folks. It works, okay? It works. Only a stupid person would say it doesn’t work. It works.”

He knew this, he said, because “very, very important people” had told him so, but were reluctant to say it out loud because of political correctness. “And you know what? If it doesn’t work, they deserve it anyway for what they’re doing to us.”

His performance thrilled the crowd, even as it did not reflect research on interrogation methods, which shows that building rapport and relationships with detainees is the fastest and most effective means of getting reliable information. Also, no country permits torture, including the United States.

Trump wasn’t concerned about truths demonstrated with research and data, or even the requirements of the law, despite his professed support of law and order. Trump appeared to be looking at the campaign the way a salesman looks at a product he wants to move. What do people want to hear? What do they feel in their gut? As long as he hit those targets, his fans would cheer him on at rallies and on social media. Trump knew his audience and how to move them, and he used misleading and false information to do so at a rate far higher than his competition.

Trump knew his audience and how to move them, and he used misleading and false information to do so at a rate far higher than his competition.

As Trump flew from rally to rally on his private jet, he pushed ahead with his personal business, once again attempting to put a Trump Tower in Moscow. He had two intermediaries trying to set up a deal with a Russian builder: Felix Sater—whom Trump, under oath, testified he wouldn’t recognize even if they were in a room together—and Michael Cohen, the lawyer who’d threatened a journalist who questioned Trump’s treatment of his first wife.

If Trump’s team could pull off the deal this time around, it would be a good one in many respects.

First, the tower would be large—at least 150 hotel rooms, 250 luxury condominiums, a spa and fitness center, high-end retail, and similarly posh office space. Trump wouldn’t have to pay a dime to get in on it, and in exchange for the use of his name, he’d get $4 million up front; a percentage of the gross sales; approval of the building’s design plans, sales, and marketing; and the rights to name the spa after Ivanka.

And finally, a successful project in Moscow could be used to bolster his political aims.

“Dear Michael,” Sater wrote to Cohen on October 13, 2015, “Attached is the signed [letter of intent], by Andrey Rozov. Please have Mr. Trump counter-sign, signed [sic] and sent [sic] back. Lets [sic] make this happen and build a Trump Moscow. And possibly fix relations between the countries by showing everyone that commerce & business are much better and more practical than politics. That should be Putins [sic] message as well, and we will help him agree on that message.

“Help world peace and make a lot of money, [sic] I would say thats [sic] a great lifetime goal for us to go after.”

Trump’s swelling business empire gave ethicists much to ponder as they considered the possibility he might be elected. The US Constitution prohibits federal office holders to receive gifts, payments, or other things of value from foreign states or representatives. If the president could accept gifts from foreign governments, then foreign governments would essentially have a clear path for buying influence.

Given the size of Trump’s holdings, the potential for abuse was vast. A Washington Post analysis found at least 111 Trump companies have operated in eighteen countries and territories across South America, Asia, and the Middle East. Trump’s companies have more than eight hundred registered trademarks in eighty countries.

Nitty-gritty details of Trump’s business were difficult for the public to assess. Trump refused to release his tax returns—making him the first major presidential candidate in forty years to do so. And while he had filled out a Personal Financial Disclosure form with the Federal Election Commission, those documents aren’t as revealing as tax returns. What’s more, Trump listed his net worth as $10 billion on his disclosure form—more than a billion higher than it had been just a few weeks before he filled it out. Given his past exaggerations and lies about his worth, people had reason to be skeptical of any claims Trump made.

Despite the potential for future conflicts, Trump continued to expand his empire and seek trademarks during his candidacy. It wasn’t just the Moscow tower, either. Trump also signed eight deals apparently connected with a potential hotel in Saudi Arabia, the Washington Post reported.

The ethics issues would be unprecedented if Trump were to be elected. But no one in the Trump camp seemed concerned about the ethics of a business relationship between Trump and Putin. In fact, they viewed it as an advantage.

“Micheal [sic],” Sater wrote on November 3, “we can own this story. Donald doesn’t stare down, he negotiates and understands the economic issues and Putin only want [sic] to deal with a pragmatic leader, and a successful business man is a good candidate for someone who knows how to negotiate. ‘Business, politics, whatever [sic] it is all the same for someone who knows how to deal.’

“Our boy can become President of the USA and we can engineer it,” Sater wrote. “I will get all of Putins [sic] team to buy in on this, I will manage this process.”

As Trump’s team angled to engineer the presidency with the assistance of Russian insiders, Russian propagandists under the direction of Putin were also working to advance Trump’s campaign. The Russian intelligence arm that collects information for the nation’s military—the GRU—hacked into the Democratic National Committee computer network in July of 2015, shortly after Trump announced his run.

By December 2015, a Russian propaganda operation known as the Internet Research Agency had started boosting Trump as a candidate.

By December 2015, a Russian propaganda operation known as the Internet Research Agency had started boosting Trump as a candidate. Funded by a Putin crony, the St. Petersburg troll farm specialized in propaganda (biased information meant to promote a particular point of view) as well as disinformation (false information deliberately issued by a government). This was intended to widen the growing ideological divide between Americans.

Some disinformation was elaborate: websites that were functioning duplicates of mainstream media ones, reporting an alleged terror attack on US soil that never happened, as well as fake information about an Ebola outbreak in Atlanta. The trolls also posted comments online and made fake Facebook pages and Twitter accounts. Putin wanted to erode faith in the democratic process in the United States, help get Trump elected, or, failing that, harm Hillary Clinton’s effectiveness as president of a deliberately divided nation.

Russia has long been hostile to the United States and to the US-led liberal democratic order in the world, but interfering directly with an election was more aggressive and ambitious than they’d ever been. Putin was angry about the Magnitsky Act and about painful and potentially destabilizing economic sanctions that followed his aggression in Ukraine. Russia had also lost its spot in an international political forum known as the Group of Eight (which was renamed the Group of Seven or G7 after the exit), a blow to Russian prestige.

Putin found a sympathetic ally in Lieutenant General Michael Flynn, the man Trump was leaning on as an informal foreign policy adviser. On December 10, Flynn traveled to Russia so he could attend the anniversary celebration for RT, a TV station funded by the Russian government whose purpose is to improve the appearance of Russia abroad. Other guests at the same dinner included Jill Stein, the Green Party presidential candidate who was, at the time, expected to siphon liberal votes away from Hillary Clinton, and Julian Assange—the editor of Wikileaks—who attended by satellite as he couldn’t attend in person.

In Russia, Flynn sat down for a forty-five-minute chat with an RT interviewer.

Dressed in a gray suit, gray tie, and gray striped socks, Flynn criticized the foreign policy of the Obama administration, which had fired him as defense intelligence chief for insubordination. Flynn also spoke of wanting to work with Russia to combat ISIS. Both the United States and Russia, he said, had been acting like “two bullies on the playground,” implying both sides were behaving equally badly.

“This is a funny marriage between Russia and the United States. But it’s a marriage. It’s a marriage whether we like it or not. And that marriage is very, very rocky right now … and what we don’t need is, we don’t need that marriage to break up.”

For Flynn’s efforts, he was paid up to $45,000, and as guest of honor, was seated next to Putin at a gala dinner. Flynn was supposed to disclose this income on federal forms, and had been informed of this at his retirement from the military. He did not.

Meanwhile, Trump kept up his tough rhetoric on immigrants—broadening his assault to include Muslims. On the seventy-fourth anniversary of the Japanese invasion of Pearl Harbor, in front of a rapt audience in South Carolina, and following a mass shooting of Americans by Muslim immigrants, Trump read a statement: “Donald J. Trump is calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what the hell is going on,” he said, to applause. “We have no choice. We have no choice.”

Trump also advocated government surveillance of mosques, a potential database to track all Muslims in the country, and a ban on refugees from Syria, a Middle Eastern country that’s been embroiled in a complicated civil war, pitting rebels against its brutal president.

Trump’s statements about Muslim immigrants struck observers as being calculated bigotry—premeditated statements he knew would score political points based on the unfounded fear that Muslim immigrants pose a serious danger to Americans.

Ibrahim Hooper, national communications director at the Council on American-Islamic Relations, told the Washington Post, “We’ve always had anti-Muslim bigots, but they’ve always been at the fringes of society. Now they want to lead it. In saner times, his campaign would be over. In insane times, his campaign can gain support.”

Not all of Trump’s shows of toughness were political. The week after his Muslim ban, he wanted to demonstrate that he was physically tough, too, so he had his doctor release a letter describing his health. Although candidates typically release their health reports, Trump’s letter was—like much of his campaign—one of a kind.

“To Whom My [sic] Concern,” the letter began. “I have been the personal physician of Mr. Donald J. Trump since 1980…. Mr. Trump has had a recent complete medical examination that showed only positive results. Actually, his blood pressure, 110/65, and laboratory test results were astonishingly excellent.”

The letter praised Trump’s “physical strength and stamina” as “extraordinary” and said, “If elected, Mr. Trump, I can state unequivocally, will be the healthiest individual ever elected to the presidency.”

As some reporters guessed, Trump dictated the letter for his doctor to sign.

The week after the physician’s note made the news, Trump garnered more headlines by saying that Barack Obama had “schlonged” Hillary Clinton in the 2008 presidential race. People who recognized the Yiddish origins of the word—which refers to male genitalia—expressed surprise Trump would be so vulgar.

Trump argued the word wasn’t crude.

“Once again, #MSM is dishonest,” he tweeted. “‘Schlonged’ is not vulgar. When I said Hillary got ‘schlonged’ that meant beaten badly.”

As 2015 turned into 2016, Trump’s team was beaten badly in its attempt to negotiate a Moscow tower. The failure was not for lack of trying. Trump’s lawyer Michael Cohen even reached out to Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov. Cohen didn’t have Peskov’s contact information, so he sent his request to the Kremlin’s general e-mail account for media inquiries.

“Over the past few months I have been working with a company based in Russia regarding the development of a Trump Tower-Moscow project in Moscow City,” Cohen wrote. “Without getting into lengthy specifics, the communication between our two sides has stalled. As this project is too important, I am hereby requesting your assistance. I respectfully request someone, preferably you, contact me so that I might discuss the specifics as well as arranging meetings with the appropriate individuals. I thank you in advance for your assistance and look forward to hearing from you soon.”

The Trump team got no response. Because the project could not go forward without Putin’s support, they shelved the idea once more. Also, there were more pressing issues, including Trump’s performance at the Iowa caucus on February 1. With the memory of Megyn Kelly’s embarrassing questions in his Fox News interview still fresh, Trump shunned the pre-caucus Republican debate. After flying into town on his deluxe 757—where he loved nothing more than blasting Elton John’s “Rocket Man” and “Tiny Dancer” at top volume as he ate fast food and Oreos from sealed packs—Trump held his own show three miles away, an event intended to raise money for military veterans and cost Fox ratings.

The show attracted a crowd of 700, and Trump claimed to have gathered more than $6 million in donations to the Donald J. Trump Foundation during the broadcast, including $1 million from his own pocket. He promised to distribute this money to charities that supported veterans, a promise journalists would track for months as part of escalating hostilities between Trump and a skeptical press.

Despite his publicity stunt, Trump lost in Iowa, coming in behind Texas Senator Ted Cruz.

Despite his publicity stunt, Trump lost in Iowa, coming in behind Texas Senator Ted Cruz.

Trump was livid. “You don’t know what you’re doing,” he told his campaign manager Corey Lewandowski. “This team is completely lost.”

Trump also laid into Cruz, who had made an incorrect robocall blast claiming Dr. Ben Carson had dropped out of the race: “The State of Iowa should disqualify Ted Cruz from the most recent election on the basis that he cheated- a total fraud!” Trump tweeted on February 3.

Trump’s team worried how his rage would affect voters. One evening, as Trump dined on a hamburger from McDonald’s, Lewandowski gave him a warning: “If you don’t start talking about what your positive vision is for the country and stop complaining about Ted Cruz, you’re going to lose.”

Trump walked out of the room without saying a word. He continued to tweet angrily about Cruz dozens of times in the days that followed. But he still won in New Hampshire on February 9, a victory that struck observers as a bellwether. The conservative National Review called it “Armageddon for the GOP Establishment.” Others predicted Trump had the party nomination in the bag.

Exit polls looked good for Trump. What he was saying on the stump aligned with what worried and frustrated New Hampshire’s conservative voters. Almost half of them expressed anger at the federal government, which was the heart of Trump’s campaign. Forty percent wanted to deport all undocumented immigrants, as Trump had pledged to do. Sixty percent expressed fear of terrorism. And even more, two thirds, favored Trump’s temporary Muslim ban.

His political instincts had paid off like a slot machine. He could be crude and combative. He could say things that were offensive or even untrue. But as long as he criticized the government and his other favorite target, the media, he could draw thousands at rallies, dominate the headlines and airwaves, and eclipse every other candidate in the still-crowded field.

He was on track to win the nomination. But he was also going to need a more robust team to bring it home. The next two months transformed his operation in that regard, especially when it came to foreign policy.

Despite his long interest in foreign policy, he had no experience. Instead of turning to members of the conservative establishment—many of whom had considered him unfit to lead—Trump hired people with less diplomatic experience, putting them under the leadership of Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions, the first senator to endorse Trump’s candidacy.

The team scooped up an energy consultant named George Papadopoulos from the defunct Carson campaign. Trump’s team also picked up Carter Page, a consultant whose firm Global Energy Capital courted Russian businesses, including businesses subject to sanctions. Page also considered himself an “informal advisor to the staff of the Kremlin” on energy issues.

Unbeknownst to Trump, the FBI had been watching Page since at least 2013, when a wiretap of suspected Russian spies revealed they were trying to recruit Page, even as they thought he was a greedy “idiot.”

Trump needed more than foreign policy expertise, though. He also needed a savvy political fixer in case the Republican elite forced Trump through a contested convention. For that insight, he turned to a veteran consultant and lobbyist named Paul Manafort, who’d sent a pair of memos to the campaign offering his services.

“I have managed Presidential campaigns around the world,” Manafort wrote. “I have had no client relationships dealing with Washington since around 2005. I have avoided the political establishment in Washington since 2005.”

That Manafort had no Washington baggage more recent than a failed Bob Dole campaign appealed to Trump. Manafort also had an apartment in Trump Tower, another pleasing fact. And there was one more factor that appealed to the deal-conscious Trump: Manafort was willing to work for free.

After Ivanka printed the memos so her father could read them, the campaign set up a meeting, and Trump liked what he saw.

“Wow, you’re a good-looking guy,” he told Manafort, who had wardrobe that he’d spent more than $1.3 million assembling, a large head crowned with thick brown hair, and deeply tanned skin.

Trump wasn’t dissuaded by the brutes, dictators, and oligarchs on Manafort’s client list. One of Manafort’s clients, Viktor Yanukovych, had been elected president of Ukraine. His presidency ended in scandal, and he fled the country amid violent protests against his leadership. After Yanukovych’s departure, Putin annexed Crimea, touching off sanctions from the United States and Europe. Yanukovych was hiding in Russia and wanted for treason when Manafort offered his services to Trump.

Another Manafort client was a Russian aluminum magnate and Putin ally named Oleg Deripaska. Manafort owed Deripaska nearly $19 million—money Deripaska wanted back. Manafort hoped his connection to Trump would help him solve that problem.

The extent of Trump’s connections to Russia were hidden. But his bragging over the years of his relationship with Putin gave his primary opponents a target. They accused him of being soft on the Russian president. By the middle of his campaign, Trump began to downplay any connection he might have with Putin.

“I have no relationship with him other than he called me a genius,” Trump said. “He said Donald Trump is a genius and he is going to be the leader of the party and he’s going to be the leader of the world or something.

“These characters that I’m running against said, ‘We want you to disavow that statement.’ I said what, he called me a genius, I’m going to disavow it? Are you crazy? Can you believe it? How stupid are they?

“And besides that, wouldn’t it be good if we actually got along with countries? Wouldn’t it actually be a positive thing? I think I’d have a good relationship with Putin. I mean who knows?”

Even as Trump cultivated a good relationship with Putin, the relationship between Russia and the United States continued to deteriorate.

During the months Trump was staffing his foreign policy team with people who made their living in rubles, Putin authorized his Russian intelligence services to kick off a second phishing expedition of high-profile Democrats and Democratic Party officials, using fake e-mails meant to trick users into disclosing their passwords. A hacker group dubbed Fancy Bear raided the Democratic National Committee servers and stole thousands of e-mails, including the ones of John Podesta, Hillary Clinton’s campaign manager.

Meanwhile, members of Trump’s campaign reached out to the Kremlin repeatedly. Papadopoulos, the young newcomer from the Carson campaign, met with a pair of Russians in London, including a woman who falsely claimed to be Putin’s niece. Papadopoulus wanted to set up a meeting between the Russian government and Trump’s campaign.

The national co-chairman of Trump’s campaign—a former Air Force colonel and Obama birther named Sam Clovis—was happy at the prospect.

“Great work,” he told Papadopoulos.

Even without having a meeting, Trump had begun saying something Putin wanted to hear: that NATO was obsolete.

“We’re dealing with NATO from the days of the Soviet Union, which no longer exists,” he told Fox News.

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization was forged in 1949 to promote democratic values, peaceful resolution to conflict, as well as cooperative national security. Russia is not one of the twenty-nine nations that takes part in the treaty. Trump had long believed that the United States was paying more than its fair share to keep the world safe.

As Trump argued for a new balance of power in the world, he faced challenges balancing the power within his campaign.

His campaign manager, Corey Lewandowski, had allegedly manhandled and bruised a reporter from the far-right Breitbart News, lunging at her during a rally as she walked beside Trump and asked him questions. Lewandowski said he never touched her, and also claimed the reporter was a “nutjob” who leaped a barricade to get access to the candidate. Video footage contradicted his claim; the reporter does not jump a barrier and lunge at Trump. She’s walking beside him, apparently asking questions. Battery charges were filed against Lewandowski, but later dropped.

What’s more, Lewandowski wasn’t thrilled with Manafort’s presence. Trump’s children, who were involved in his campaign as they were in other parts of his business, liked Manafort. When Trump lost the Wisconsin primary on April 5, coming in thirteen points behind Ted Cruz, it was only a matter of time before Manafort got the reins.

One of the first things Manafort did was to try to make Trump seem more presidential, as he’d done for Yanukovych in Ukraine. That meant no more freewheeling TV appearances.

Trump was traveling in his helicopter when he found out Manafort wanted to keep him off TV. He forced his pilot to lower the chopper enough to get cell service.

“Did you say I shouldn’t be on TV on Sunday?” he asked Manafort. “I’ll go on TV anytime I g–dam f—ing want and you won’t say another f—ing word about me! Tone it down! I wanna turn it up! I don’t wanna tone anything down!”

Despite this miscalculation, Manafort gained increasing control over the campaign, and increasing scrutiny from reporters, who were aware of his links to Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs. When reporters asked the campaign about Manafort’s dealings with Deripaska and a Ukrainian businessman, he told spokeswoman Hope Hicks to ignore the questions. That turned into wishful thinking on his part.

Meanwhile, Trump delivered his first foreign policy speech, drafted with help from Papadopoulos, at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC, on April 27. Wearing a dark suit, American flag pin, and brilliant red tie, Trump read from a teleprompter:

“America First will be the major and overriding theme of my administration,” he said. “But to chart our path forward, we must first briefly take a look back. We have a lot to be proud of.

“In the 1940s we saved the world. The greatest generation beat back the Nazis and Japanese imperialists. Then we saved the world again. This time, from totalitarianism and communism. The Cold War lasted for decades but, guess what, we won and we won big. Democrats and Republicans working together got Mr. Gorbachev to heed the words of President Reagan, our great president, when he said, ‘tear down this wall.’”

As much as Trump intended to look back on proud moments in US history, the phrase “America First” is associated with policies that would have prevented those proud moments. In 1940, an America First Committee was founded to keep America from taking part in World War II. As many as a million joined the movement, including socialists, conservatives, future president Gerald Ford, Peace Corps founder Sergeant Shriver, and prominent anti-Semites, including the pilot Charles Lindbergh, automaker Henry Ford, and Avery Brundage, a former US Olympic Committee chairman who’d refused to let two Jewish track stars compete in the 1936 Olympics.

Trump’s speech alarmed America’s traditional allies in Europe.

Trump’s speech alarmed America’s traditional allies in Europe. Hearing the echo of earlier US isolationism, some took the unusual step of criticizing the candidate’s words.

A former Swedish prime minster, Carl Bildt, said Trump’s speech sounded as if he was “abandoning both democratic allies and democratic values” while staying silent on Russian aggression in Ukraine.

One potential reason for Trump’s silence on Russia’s actions: the country’s ambassador to the United States, Sergey Kislyak, was sitting in the front row during the speech.

Kislyak had already met with Sessions to discuss US policies of interest to Russia (though Sessions would later deny it had any relation to the campaign). At a reception before the speech, Kislyak met Ivanka’s husband, Jared Kushner, one of Trump’s chief advisers in his campaign, and a fellow real estate developer who, like Trump, had inherited a business from his father.

The meetings might have seemed insignificant at the time. They would not seem that way later to the FBI.

The meetings might have seemed insignificant at the time. They would not seem that way later to the FBI.

Meanwhile, Trump was still trying to knock out his competition. A few days after his foreign policy speech at the Mayflower, he called Fox & Friends to share a conspiracy theory about his rival Ted Cruz. It was a tidbit about John F. Kennedy’s assassin that Trump had read in the National Enquirer, a supermarket tabloid run by a Trump ally named David Pecker.

Trump told the hosts, “[Ted Cruz’s] father was with Lee Harvey Oswald prior to Oswald’s being—you know, shot. I mean, the whole thing is ridiculous. What is this, right prior to his being shot, and nobody even brings it up. I mean, they don’t even talk about that. That was reported, and nobody talks about it.”

“What was he doing with Lee Harvey Oswald shortly before the death? Before the shooting?” Trump said, implying that Cruz’s father had something to do with the assassination, and that the collective media silence was a cover-up orchestrated by journalists around the globe. “It’s horrible.”

Cruz rejected the insinuation in blunt terms, calling Trump “a pathological liar.”

The Texas senator had nothing to lose in saying that; he dropped out of the race that night, making Trump the presumptive Republican nominee.

During those same weeks, Papadopoulos kept pushing the prospect of meetings with the Kremlin, including with members of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which he reported was “open for cooperation.”

Clovis, the birther, wanted Papadopoulos to hold off: “There are legal issues we need to mitigate, meeting with foreign officials as a private citizen.”

Clovis might have been referring to the Logan Act, a rarely prosecuted law passed in 1799 that makes it a crime for private citizens to negotiate with foreign governments that have disputes with the United States. No one has ever been convicted of violating the act.

Although he didn’t get the meetings he wanted, Papadopoulos remained excited about the prospect of working with Russian officials to help Trump.

“It’s history making if it happens,” Papadopoulos wrote to one of his sources.

A couple weeks after Trump’s speech, during a night of drinking in a cozy, brick-walled wine bar in London’s Notting Hill neighborhood, the dark-haired Trump aide told Australia’s top diplomat that the Russians had Clinton’s e-mails and “dirt” on the candidate.

Months later, the diplomat would remember this conversation when stolen e-mails were released by Wikileaks, the organization run by Julian Assange, a host of a show on RT, which would participate in Russian efforts to influence the election.

As much as Trump’s campaign wanted to meet Russians close to Putin, Russian oligarchs also wanted to lend support to Trump. Aras Agalarov, who worked with Trump on the Miss Universe pageant in Moscow, sent Don Trump Jr. a letter in February through his pop-star son’s publicist, Rob Goldstone.

“Emin’s father has asked me to pass on his congratulations … offering his support and that of his many important Russian friends and colleagues, especially with reference to US/Russia relations,” it read in part.

Prominent Russians with close Putin connections wanted to meet Trump as well. A banker named Alexander Torshin tried to meet the candidate when he was in town as the guest of honor at the annual National Rifle Association convention in late May. The deputy governor of Russia’s central bank—a suspected money launderer being wiretapped by Spanish authorities—met instead with Trump’s son Don, a meeting noted by the Guardian Civil, Spain’s national police.

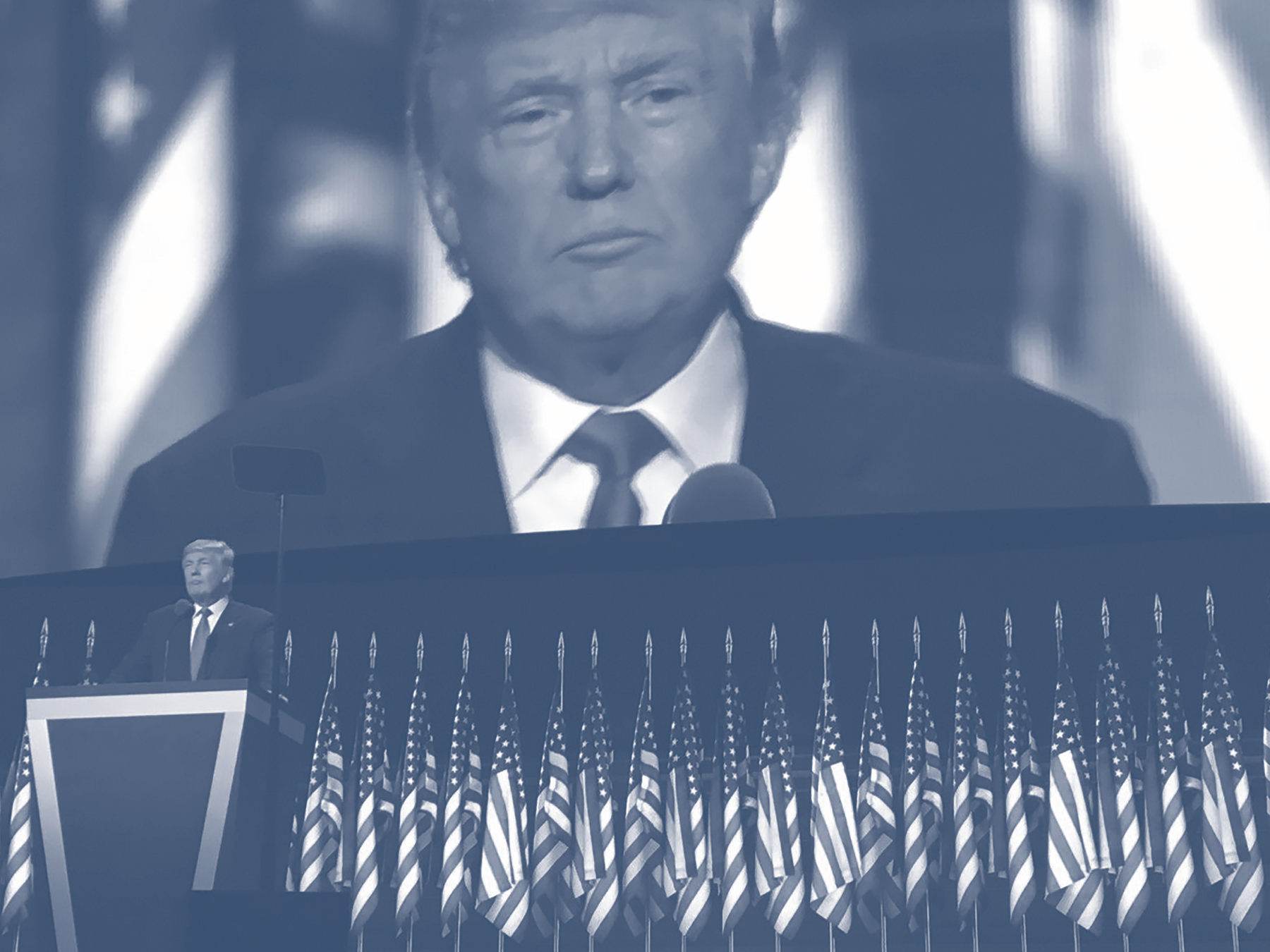

At the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio, Donald Trump accepts the party’s presidential nomination. July 21, 2016. (Nicolas Pinault/VOA)

BY SUMMER, THE NEARLY IMPOSSIBLE HAPPENED. Trump had gathered enough votes from delegates to win the Republican nomination. The journey had been a wild one, the culmination of a notion Trump had hatched as early as 1980, when he had that interview with Rona Barrett. Written off as a joke at first, Trump turned his campaign into a juggernaut, commanding billions of dollars in free media coverage with his blunt, blistering, and often baseless assertions. There was always a chance that delegates would refuse to cast their ballots for him, but that’s why he had Manafort on board.

Trump’s next challenge would be his biggest yet: On June 6, former Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton had earned enough delegates to become the presumptive Democratic nominee. She was one of the most experienced candidates in history, and almost no one thought Trump could beat her.

A brutal campaign was about to get uglier in public.

A brutal campaign was about to get uglier in public. Behind the scenes, it was about to become the subject of an unprecedented investigation by the FBI.