COOK formally joined the Navy at Wapping on 7 June 1755 and was assigned to the Eagle, Captain Joseph Hamar, a 60-gun ship moored at Spithead. There has been fanciful speculation that the recruiting officer must have been delighted at such a catch volunteering as a mere seaman, but it is more likely that the signing of Cook was all in a day's work. To Cook the hierarchy in the Royal Navy was something new, for on His Majesty's ships executive decisions were shared between the captain and the master. Within a remarkably short time – almost exactly a month – Hamar had spotted his latest recruit as ‘one to note’ and promoted him to master's mate, the master being Thomas Bissett.1 The Eagle itself was in poor shape, having emerged from Portsmouth docks in a state of semi-repair two months before Cook joined her. It took three months to make her seaworthy, in which time her sailing orders were changed from the interdiction of French commerce with the French West Indies to a supporting role in Admiral Hawke's blockade of the Brittany coast, operating mainly between the Scilly islands and Ireland.2 Although war had not yet been formally declared between Britain and France, a state of war existed between the two nations. It would take more than a year before the struggle for mastery in the Americas was subsumed in the wider European conflict known to history as the Seven Years War. Perhaps Captain Hamar was impressed by Cook simply because he could delegate so much responsibility to him. The inference that Hamar was a fainéant, lethargic and lacklustre skipper is strengthened by his actions once at sea. First he mistook a Dutch merchantman for a French warship. Then, when gales and squalls battered his ship, he decided to run for home. The last straw was a ‘monstrous great sea’ off the Head of Kinsale in Ireland. The Nelson touch was distinctly lacking in Hamar and the beginning of September found him back in safe anchorage at Plymouth, ostensibly because the mainmast was sprung between decks.3 But the shipyard repairers found nothing wrong with the Eagle after two weeks of exhaustive investigations. The Admiralty testily ordered Hamar to put to sea at once, but the reluctant captain found a fresh reason for delay, this time pleading the necessity to put the vessel into dock to have its bottom tallowed. This was too much for the Lords of the Admiralty, who abruptly dismissed Hamar from his command.4

The new captain, Hugh Palliser, was to be a key figure in Cook's career and featured as the third of his great patrons, after Skottowe and Walker. It would transpire that Cook's gamble had paid off, that his luck had held and that he had yet again found a powerful protector. Palliser, five years Cook's senior, had already been at sea for twenty years, having gone to sea aged 12, despite being the son of an army captain and of gentry stock in the West Riding. He passed all his examinations and became a lieutenant aged 18 – according to Admiralty regulations, three years before any man should receive a commission.5 A veteran of the War of the Austrian Succession, he had been in action at the battle of Toulon in 1744 (when Cook was still tending sheep) and gained his first command in 1746, when Cook began his apprenticeship with Walker. Since then he had clocked up service off the Coromandel coast in India, in the West Indies, on patrol off the English coast and in transatlantic convoy duties. His career illustrated how far behind the high-flyers Cook was at this stage. Palliser seems to have noticed Cook's talent right from the start, and perhaps the common Yorkshire background was also an element in the solidarity he always showed with his younger subordinate.6 Capable and energetic, Palliser displayed none of Hamar's timidity. Once out at sea on 8 October, with orders to cruise the western approaches as part of a general blockading force under Admiral Temple West and the ill-fated vice-admiral John Byng, Palliser ran into the storms, gales and monstrous seas that had knocked the sand out of Hamar. Dispirited by the wind and waves, the sailors nonetheless rallied to Palliser with gusto, motivated by the mouth-watering prospect of prize money. Administered by a Navy agent, prize money, rated according to the value of the enemy ship captured, was divided into eight parts, of which the capturing vessel's captain was given three-eighths, the commander-in-chief one eighth, the officers one-eighth, the warrant officers one one eighth, and a quarter to the men. This meant that an officer could collect well over £1,000 while even an ordinary seaman could hope for £100 – a vast amount given general wage levels at the time. The greatest prize ever taken was in 1762 when the Spanish treasure ship Hermione was intercepted out of Peru, and the lowliest seamen received the staggering sum of £485 each.7

Leaving Plymouth on 8 October, the Eagle was for five weeks mostly on her own. Ploughing through hard gales and white squalls, she chased any sail that appeared on the horizon, but most of these proved to be neutral merchantmen: Spanish, Swedish, Dutch, German. She managed to haul in a few minnows in the shape of French fishing boats returning from the Newfoundland Banks, but significant quarry eluded her. On the one occasion she came close to a major capture, a sister ship, the Monmouth, nipped in to scoop the prize. The weather continued to be atrocious, and in early November Palliser lost his main topgallant mast in a severe squall. On 13 November he joined West and Byng in the Bay of Biscay and helped them to bring down major prey in the form of the 74-gun Esperance, which sank after a long-running fight with West's squadron; the encounter, in a heavy gale, was something of a foretaste of the battle of Quiberon four years later. With his ships badly battered both by the gales and French guns, Byng ordered a return to Plymouth for a major overhaul and refit. The Eagle was thus out of action from 21 November to 13 March 1756. The crewing situation on board was now chaotic, and Palliser wrote to the Admiralty to complain of inadequate manning; that is, the undermanning that would result once he had stripped from his ship the supernumeraries, invalids and other sick or incapacitated men who had been dumped on him during the short cruise of October–November.8

Cook meanwhile continued to find favour with his new patron. On 22 January 1756 he was promoted to boatswain, responsible for ropes, sails, cables, anchors and flags as well as boats, and thus securing a pay rise from £3 16s. to £4 a month. But Palliser continued to employ him also as master's mate, so the promotion may have been more apparent than real as Cook was now in effect doing two jobs. Perhaps as a consequence in February we find Cook in sick bay with an unspecified illness.9 On 13 March the Eagle put to sea again. She arrived off Cape Barfleur on the Cherbourg peninsula on the 19th and joined two other ships in surveillance of the port of Cherbourg. The weather was once more bad and there was little to assuage the boredom of routine patrol except a few picayune encounters with French smugglers. For two weeks in April Cook was given temporary command of one of the Eagle's cutters, which moved in close to the Brittany coast at Morlaix.10 When Palliser was suddenly ordered to return to Plymouth, Cook had to find passage on the commodore's ship Falmouth in order to regain his own ship. But once more he was assigned independent cutter duty, this time accompanying Admiral Edward Boscawen from Plymouth to Ushant aboard the 60-gun St Alban's. It was 3 May before he rejoined the Eagle, which was now definitively part of Boscawen's armada attempting to bottle up the French fleet in Brest – for war had been formally declared in May. And now at last the Eagle finally secured a prize, albeit a minor one – a vessel from the West Indies carrying tea and coffee. Cook was sent back to Plymouth with the prize and then had to take it round the coast to London. He was back in Plymouth on 1 July to find the Eagle refitting but Palliser in despair at the swathe that illness had scythed through his crew, with 27 already dead and another 130 in hospital, most of them seriously ill.11

Palliser now applied to the Admiralty for warm clothes for all pressed men and an extra ration of food; surprisingly, his request was granted.12 The next to fall sick was Palliser himself, so that for a very brief interval Cook served under a new captain, Charles Proby. But Palliser was soon back on the bridge, and in early August the Eagle was ready to sail again, after extensive repairs.13 What followed was opéra bouffe. A Swedish merchantman had reported seeing a squadron of nine 90-gun French warships off the Isle of Wight. The Eagle was one of those ordered by Rear Admiral Harrison to investigate, intercept and interdict. When no signs whatever of such an armada were found, it was suspected that the Swede might be a French agent who had deliberately planted disinformation. In retaliation, the British kept him at Portsmouth for several months, looking into ‘irregularities’ in his ship's papers.14 The Eagle was then detached to assist in Boscawen's blockade off Ushant, but her long cruise in the Atlantic was tedious and uneventful. By the time she headed back to Plymouth in mid-November disease once more stalked the ship; morale was low, and the exiguous prize money doled out for the the Eagle's petty captures scarcely improved matters.15

By the end of 1756 the Eagle had brought her crew up to full strength (around 420 men) and set out again on her tedious blockading duties. Only five days out she was caught by a ferocious gale off the Isle of Wight which ripped away most of her sails. Back into Spithead she went for another month in the doldrums, until on 30 January she sailed again with Vice-Admiral West's squadron, this time to the Bay of Biscay. Another uneventful period ended on 15 April with shore leave in England. On 25 May 1757 the Eagle put to sea again in company with the 60-gun Medway, and this time saw some stirring action. Palliser, evidently a better seaman than the Medway's captain Proby, managed to engage the 50-gun French man-o'-war the Duc d'Aquitaine out of Lisbon while Proby's incorrect sailing instructions left his ship out of the picture. After an hour's fierce pounding, the French vessel was disabled in the main and mizzen masts, and struck. Here at last was a major prize.16 This was Cook's first experience of naval combat, and a grim business it proved, with twelve of the Eagle's crew dead and eighty wounded, while the French suffered casualties of fifty dead and thirty wounded. Cook was rewarded by promotion to master, and thus escaped the violently tempest-tossed Atlantic crossing to which Palliser and the Eagle were next assigned. When Palliser and his leaking ship limped back to England in late September, having been reduced to jury masts and with a crew decimated by disease, he was perhaps not in the best state of mind to receive a well-meaning but politically naïve intervention by John Walker and William Osbaldeston, MP for Whitby, petitioning for a commission for James Cook. With as much patience as he could muster, Palliser wrote back to say that preferment was beyond his ability to confer; he stressed that naval regulations could be waived only if one of the great and good of Georgian England entered the lists on behalf of a protégé, and neither Osbaldeston nor Palliser himself fell into that category. According to the regulations, Cook would have to serve as a mate for at least six years before he could be considered for a commission, so he was at least four years shy of the target.17

Even though Walker's ham-fisted efforts on his behalf had failed, Cook himself was in good spirits. Shortly after returning from the capture of the Duc d'Aquitaine, he passed his examinations (held at Trinity House, Deptford) and qualified as a ship's master. Theoretically, Cook had now reached the farthest point a meritocrat could go in the Navy without capital, and even so most masters usually owned shares in their ships.18 He was the chief professional on board, though not of course the highest ranking one. His sphere was the navigation of the ship, its general management and its stores, and he had overall responsibility for masts, yards, sails and rigging, whose day-to-day details devolved to the boatswain. It was he who kept the ship's log. He was also supposed to be the brains behind pilotage and harbour work, responsible for taking soundings and bearings and, crucially, making new charts and correcting the existing ones. Ubiquitous and omnipresent, the master represented the heart of the ship and the captain its head. There was almost a sense in which the master was outside the normal ranking in the hierarchy, for he alone wore no uniform. The captain was in charge of strategic and tactical decisions and was ultimately answerable to the Admiralty for the conduct of the ship, but shrewd captains usually took care to heed the advice of their masters and not override their prerogatives or question their expertise. A good master was a prized asset, but his very excellence could work against him, for the Admiralty did not tend to waste precious talent by promoting such a person. Masters, like boatswains, pursers, gunners, carpenters and cooks, were sometimes given the misnomer ‘standing officers’, which in theory meant that they were tied to a given ship in perpetuity or unless it was lost. In fact such men were often promoted from small ships to large ones, and even exchanged duties with each other, swapping with those who wanted to go to sea, and vice versa. In sum, the master was the most senior of the warrant (non-commissioned) officers and in some respects, including pay, his status equalled that of a lieutenant.19

Reluctantly Palliser had to discharge Cook from the Eagle. At the beginning of July 1757 he was assigned the position of master on a 24-gun frigate, the Solebay, captain Robert Craig. The Solebay's duties were to patrol the east coast of Scotland to prevent smuggling or raids by French privateers. Cook travelled overland via Yorkshire and visited his parents and John Walker before joining his ship at its base in Leith on the Firth of Forth on 30 July. Sailing two days later, Cook got his one and only look at Scotland on a voyage to the Shetlands, calling at Stoneham (Kincardineshire), Buchan Ness (Aberdeenshire), Copinsay and Fair Isle in the Orkneys before anchoring in Lerwick harbour.20 The inconsequential foray into the North Sea ended with the Solebay back in the home port of Leith by the end of August. Cook does not appear to have been aboard for much more than another week or so before he was transferred to the Pembroke where he superseded his old friend Bissett, whose mate he had been on the Eagle.21 The Pembroke was a state-of-the-art 64-gun warship, 1,250 tons, captain Simcoe, and the appointment to be her master was considered prestigious. Cook joined his new ship in Portsmouth, where it had been fitting out after a cruise to Lisbon,22 and was soon again in familiar waters, down the Channel and south into the Bay of Biscay and on to Cape Finisterre, once more in pursuit of an enemy who never appeared. On 9 February 1758 the Pembroke was back in Plymouth, but this time the Admiralty had great and ambitious designs for the ship: she was to take part in Prime Minister William Pitt's attempt to destroy the French in North America.

Pitt's master strategy was to use the well-funded National Debt as the financial basis for making large subsidies to Prussia and its German allies in Europe, while concentrating on the global struggle against France in India and the Americas. Until the end of 1757 the war in North America had overwhelmingly gone France ‘s way. Their talented general Louis-Joseph Marquis de Montcalm had won a string of victories over the British, including the particular humiliations at Monongahela in 1755 and Fort William Henry in 1757.23 Now Pitt aimed to reverse the trend, and he began by sacking the British commander-inchief in North America, Lord Loudoun, and replacing him with General James Abercromby. Pitt always had the Napoleonic gift of luck, and by the beginning of 1758 a unique conjuncture of events favoured his designs. On at least half a dozen different indices the pendulum in North America was about to swing decisively. The deep, overarching factor that would secure British triumph in less than three years was sea power. With its decisive command of the seas, the Royal Navy could slowly begin to throttle the French colony in Canada; New France, as it was called. The interception of ships bearing supplies and reinforcements from France was part of a slow but sure process of remorseless attrition that would eventually consign French Canada to its fate.24 At the same time Pitt reversed Loudoun's self-defeating policy of trying to make the anglophone North American colonists pay for British military endeavours. Instead he decided to subsidise them and pay bounties to native recruits. The upshot was that when he implemented his massive multi-front campaign against New France he could pit at least 14,000 redcoats and up to 25,000 colonial irregulars against French forces that were numerically far inferior. Montcalm commanded at most 6,800 French regulars plus 2,700 marines; in addition there was a raw militia of dubious military worth, maybe 16,000 strong, composed of all able-bodied males between 15 and 60.25

Before 1758 the French had been able to compensate for the disparity in numbers by calling on their Indian allies, espcially the Abenaki and Micmacs, to redress the balance. But in early 1758 the tribes were hit by a devastating smallpox epidemic that took them out of the picture. Meanwhile New France was suffering dire shortages of food and supplies, exacerbated by the failure of two consecutive harvests, in 1756 and 1757. French Canada was on starvation rations over the winter of 1757–58, even as the corrupt intendant François Bigot, who was supposed to guarantee the food supply, made a private fortune for himself through a series of scams and defalcations.26 Montcalm and the governor of New France, Pierre Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil, loathed each other, so that there were divided counsels at the top about how to deal with the British threat. Moreover, France itself was paralysed by financial chaos and political indecision. Inflation was rampant: France spent two million livres a year on Canada in 1754 but by 1757 the costs had escalated to 12 million. In Canada itself inflation meant that merchants and farmers started hoarding, while Bigot's unwise attempt to force his business community to accept worthless paper money simply meant that all specie arriving on ships from France was likewise squirrelled away against the day when financial stability would return.27 In the political sphere Louis XV had no ministers of any ability on his council until the very end of 1758, when the Duc de Choiseul became Foreign Minister. At the very moment Pitt had decided to hold the ring in Europe and concentrate on the struggle in the colonies, France moved in the opposite direction. Its grand strategy of 1758 – in so far as anything deserving that title can be discerned – stressed the European theatre: victory in Germany and the preparation of an armada to invade England became the priority, and New France was neglected.28

Against this dispiriting picture of waning French power, with factionalism, corruption and economic chaos rampant, Pitt had the advantages of naval hegemony, clean and uninterrupted supply lines and a united command. Although Pitt himself liked to take credit for the grand strategy of 1758 in the Americas, the true military mind behind it was Field Marshal Ligonier. He it was who suggested the offensive in North America and he too who appointed (over the strenuous opposition of George II), four talented generals to serve under Abercromby. The campaign would be three-pronged. Abercromby, supported by George Augustus, Viscount Howe, would advance overland against Canada via Lake Champlain, aiming at Fort Carillon. John Forbes, the second of the quartet, would attempt to capture Fort Duquesne and Fort Frontenac at the forks of the Ohio river.29 The other two of Ligonier's ‘four musketeers’, Jeffrey Amherst and James Wolfe, were given the task of taking the fortress of Louisbourg so that there would be no French garrison in the British rear when they advanced up the St Lawrence river to attack Quebec. Loudoun's view had been that Louisbourg was unimportant and could be bypassed by an expedition bound for Quebec, but neither Pitt nor Ligonier accepted such optimistic thinking. A crucial part of the strategy was that major detachments of the the Royal Navy would cross the Atlantic and remain on station off the American coast to give Wolfe and Amherst all necessary back-up. The man given command of the naval contingent was Admiral Edward Boscawen, a hero because of his achievements in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48). Called ‘Wry Neck Dick’ from his habit of cocking his head to one side (allegedly the result of a war wound), Boscawen already had credentials in combined operations, having covered the siege of Pondicherry in India in 1748 with warships.30

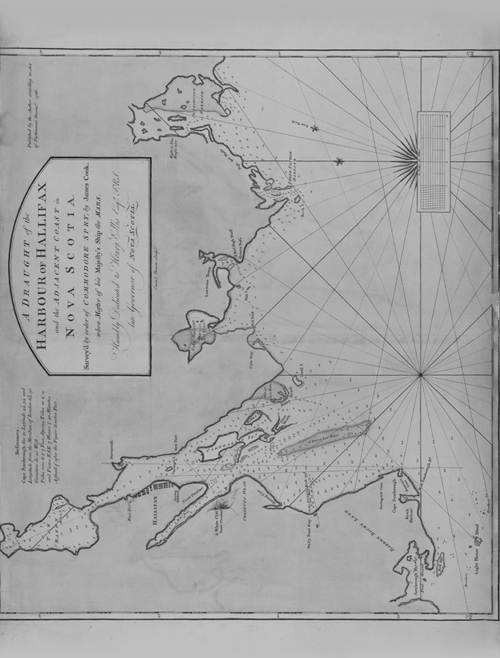

Boscawen's armada comprised eight ships of the line and several smaller vessels. It was with Boscawen's fleet that Cook sailed in the Pembroke, one of the eight warships, from Plymouth on 22 February 1758. To be more precise, the Pembroke seems to have joined an expedition that was already at sea, for Boscawen and most of his ships left St Helen's on the Isle of Wight on the 19th.31 The ships soon ran into storms and high seas, and the less robust members of the assault force surely quaked in their military boots, for this seemed an ominous rerun of the disaster of the year before. In 1757 Loudoun had attempted to besiege Louisbourg but was forced to call off the attempt. At the end of September the British fleet that had been playing a key role in combined operations was caught by a frightful hurricane about thirty miles off Louisbourg which ‘in another day, if it had continued, would have destroyed them all’.32 It was this encounter with the elements that had left the Eagle looking like a ghost ship. This time the storms did not quite reach hurricane force, but they were enough to alarm all normal souls. Wolfe, aboard the Princess Amelia, later recalled that ‘From Christopher Columbus's time to our days there perhaps has never been a more extraordinary voyage.’33 Cook, by contrast, treated even the most severe storms with insouciance, noting the wind force with clinical detachment, almost as if he was already convinced of his ability to deal with the very worst the oceans could throw at him. It seems that the convoy shifted track several times to avoid the battering from gales, for an itinerary from England to Newfoundland via Tenerife and Bermuda makes no sense otherwise. It was 9 May before the weary Pembroke reached Halifax, the port the British had built up as a counterweight to Louisbourg. Twenty-six men had died on the passage, and many others were hospitalised as soon as the ship anchored in the port; additionally there were five desertions.34

Halifax, on the Nova Scotian coast, was about two days' sail (that is, in good weather) from Louisbourg, which was on the south-eastern corner of Cape Breton island, and commanded the approaches from Newfoundland to the St Lawrence. An important town, port and fortress, it was the centre of the French fishing industry in the New World and possessed a kidney-shaped harbour capacious enough to contain a large fleet. The British had captured it in 1745, and the French had made a major attempt to retake it in 1746. Where military effort failed, diplomacy succeeded and, at the end of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748, France regained the town in exchange for giving up Madras in India. Determined not to let Louisbourg fall into British hands again, the French then tried to turn it into an impregnable fortress, and it certainly looked impressive to the casual observer, yet the appearance belied the reality. There were formidable gun emplacements in the fortress, shore batteries and eleven warships in the harbour. But the imposing-looking walls had been weakened by damp in the mortar, and the landward fortifications were poorly sited. On the other hand, these weaknesses could be exploited only by an invader prepared to launch a daring amphibious assault.35 At first the very elements seemed tilted against a British success. During the crossing the storms had scattered the fleet and when Boscawen and Wolfe arrived in Halifax in early May there was no sign of Amherst. They were already a month behind schedule in the very tightly plotted military scenario for 1758. They therefore laid plans in accordance with the contingency instructions from Pitt in case Amherst was lost or delayed. They were just about to clear for Louisbourg when Amherst finally arrived on 28 May. As a point of principle, he changed the plan Wolfe had elaborated for the capture of Louisbourg, insisting that they land at Gabarus Bay under the enemy's big guns, rather than make a ten-mile march there overland.36 But even the short trip from Halifax to Louisbourg was dangerous, with the fleet once more being dispersed by a gale (on 30 May).

Finally, with 157 transports and warships, and 13,000 troops, Amherst and Wolfe came in sight of their objective. Their overall aim was to land, secure a beachhead, then gradually spread out to envelop the harbour and steadily advance on the fortress itself, which they would reduce to rubble with big guns. The French governor, Augustin de Boschenry de Drucour, watched the enemy's approach with apprehension, well aware of the intrinsic weakness of his position and grimly conscious that he was outnumbered: he had a garrison of 3,500 troops and could summon perhaps that number again from the warships in the harbour.37 The British were ready to launch their amphibious assault by 3 June but, with a 15-foot surf running, dared not attack. On the 4th Amherst decided that his original plan of attacking in three waves was too ambitious; there would be just one landing, led by Wolfe, and spearheaded by 3,000 of his crack troops.38 But high winds, a heavy swell and fog delayed the attack for another four days. Only on 8 June were weather conditions suitable. The French still remained confident that the narrowness of the beach and the continuing surf would turn any assault into disaster. The landing was touch and go but ultimately successful. The vainglorious Wolfe, who later claimed the credit for everything, at one moment signalled retreat – only to have the order ignored by some intrepid Highlanders.39 Once they had secured a beachhead the British were already two-thirds of the way to success. The next task was the destruction of the French warships, which was achieved by non-stop cannonades and mainly completed by 21 July. Sailors from Boscawen's fleet, concealed by a thick fog, entered the harbour in boats. The circle was closing, but the real coup de grâce for the French was the non-stop twelve-hour bombardment of the town on 25 July, during which 1,000 rounds of shot and shell rained down on the beleaguered citadel.40 Next day Ducour hoisted a flag of truce and asked for terms. The six-week siege had turned out triumphantly for Amherst, but its conduct was marred by systematic atrocities and the deliberate massacring of all Indians in revenge for the defeat at Fort William Henry the year before. Both Amherst and Wolfe were hard, ruthless men, habitually addicted to war crimes and even genocide. In contrast to Montcalm's chivalrous instincts at Fort William Henry, Amherst denied Ducour all honours and insisted as part of the surrender terms that all French combatants be sent to England as prisoners of war; meanwhile the civilian population was to be deported to France.41

Cook made no comment on this departure from the norms of civilised warfare, but then he was always very careful never to make critical comments about his superiors and ‘betters’. In any case he did not see much of the siege of Louisbourg for, when Boscawen departed on 28 May, the Pembroke remained in Halifax, waiting for her quota of sick to be released from hospital so that the vessel once more had a credible crew. The ship cleared from Halifax on 7 June but was then (one is tempted to say inevitably) delayed by storms and gales, and so did not reach Louisbourg until the 12th. The Pembroke had not been long at anchor in Louisbourg before she and others had to cut their cables and run for the open sea to avoid being overwhelmed by a severe gale; they were then at sea for a further two days.42 Cook finally got into action just before the French surrender. The 21st of July was a black day for the French, for three of their warships, the Célèbre, Entreprenant and Capricieux were destroyed by British gunnery. With the frigate Aréthuse having made a daring escape from the harbour on 15 July, bearing the grim tidings of Louisbourg's likely fate to France, that left just two warships on which Ducour could pin his slender hopes: the Bienfaisant and Prudent.43 Boscawen decided that these two, of 64 and 74 guns, respectively, should be ‘taken out’ by boarding parties attacking in boats. A night-time assault on the evening of 25 July by two divisions of 300 men each, in fifty boats with muffled oars and hooded lanterns, was amazingly successful. The assailants achieved complete surprise in overrunning the Prudent and, although the crew of the Bienfaisant made more of a fight of it, the ultimate result was the same. Whether by accident or design the Prudent was set on fire and gutted.44 The loss of the final two warships, allied to the twelve-hour bombardment of the fortress, gave Ducour no choice but surrender. Boscawen, Amherst and Wolfe congratulated themselves on a signal example of inter-service cooperation. Not only had the amphibious operation at Gabarus Bay on 8 June been a total success, but Amherst's request to Boscawen to destroy the enemy warships had been clinically and efficiently carried out.45

The day after the French surrender was a significant one in Cook's life. He went ashore at Kennington Cove, the precise location on Gabarus Bay where Wolfe had made his landing seven weeks previously. Soon his attention was caught by a man who seemed to be carrying out mathematical observations with the use of a square table and tripod, making notes all the while. Cook engaged the man in conversation and the latter introduced himself as Samuel Holland, a military surveyor. A Dutchman, born in the same year as Cook, he had served in the Army of the United Provinces before being commissioned as a lieutenant in the British Army in 1755. He went to North America with Loudoun in 1756 and had served with distinction in some of the nasty skirmishes in the Hudson River/Lake Champlain corridor, where he had surveyed Fort Carillon (Ticonderoga).46 Evidently a man of some real verve and charm, he was even on friendly terms with the notoriously vain and prickly James Wolfe, to whose staff he was then attached. He and Cook took an immediate liking to each other, for Holland soon recognised a serious professional rather than one of the aristocratic fops in which the upper echelons of the British armed services then abounded. He explained that his plane table enabled him to make accurate surveys. He would sight over the top at distinguishing marks on the horizon and then make careful notes of his observations. This allowed the creation of an accurate diagram in which all physical features could be placed in relation to each other. Cook was at first fascinated, then besotted: he had found another obsession to add to his mastery of navigation and hydrography. Over the next weeks the friendship and professional collaboration with Holland ripened and deepened, and was enhanced when Cook reported his ‘Eureka!’ moment to Captain Simcoe.47 The captain expressed an interest in Holland and invited him to dine on the Pembroke. Soon the trio of Cook, Holland and Simcoe were like the three musketeers, all for one and one for all. One of the advantages of the long, stormy traverse of the Atlantic was that Cook had created another fan in Simcoe, who thus joined the long line of Cook promoters which now included Skottowe, Walker, Palliser and Captain Richard Ellerton (of the ‘cat’ Friendship).48

Despite the triumph of Louisbourg, Pitt's grand design of 1758 was thrown off balance by Montcalm's defeat of Abercromby at Ticonderoga in July – a signal disaster made worse by the death of the popular Lord Howe. Compensation in the shape of the capture of Fort Frontenac, taken by the ingenious Colonel John Bradstreet, and of Fort Duquesne, taken by General Forbes, came too late in the year for Amherst to feel confident of pressing on with the assault on Quebec.49 The late arrival at Halifax, the six-week siege of Louisbourg and the major setback at Ticonderoga combined to produce a situation where it was too late in the year to proceed with the would-be pièce de résistance of the campaign. Amherst sailed for Boston at the end of August to rally Abercromby's defeated army and make the city his base for the winter. Meanwhile the deeply unpleasant Wolfe (for two hundred and fifty years now the subject of unaccountable British imperial hero worship), revealed himself in his true colours. First, he sailed for the Gaspé Bay in the Gulf of St Lawrence and began a campaign of devastation aimed at destroying the French fishing industry. Wolfe had already proved in Scotland after the ‘45 that he was by any standards a war criminal, and now he undertook a vindictive programme of vicious brutality.50 Secondly, in correspondence with Amherst and Pitt, he meanly and despicably traduced the Royal Navy, and especially Sir Charles Hardy, for an allegedly lacklustre performance at Louisbourg, even though it was the Navy that had eliminated the French warships, and would prove the key to Wolfe's ultimate apotheosis as the conqueror of Quebec. Thirdly, although supposed to winter over in Halifax, Wolfe unilaterally decided that this did not suit him, so he fabricated a pretext to enable him to return to England, despite the furious reprimand of the Secretary of War Lord Barrington.51 Pitt and his circle had, however, created a Frankenstein's monster. Having built Wolfe up in the press as a great, glorious hero, they could hardly now portray him as an insubordinate glory-hunter without undermining their own credibility. Accordingly, Wolfe got away with what he did. He embarked with Boscawen's fleet on 1 October and spent the winter of 1758–59 in England.

It was Cook's fate at this juncture to have his career embroiled with that of Wolfe, and not just in the mutual relations with Samuel Holland. When Wolfe went on his savage war against the French fisheries in the St Lawrence with his three battalions of redcoats, Sir Charles Hardy escorted him with a squadron that included the Pembroke. So Cook was forced to endure what Beaglehole has called, with considerable understatement, ‘inglorious service’.52 The Pembroke managed to take a few small prizes, and uplifted cargoes of bread, butter and wine, thus further impoverishing the wretched French fishermen, but the real significance for Cook of the Bay of Gaspé interlude was the harmonious bonding of the trio of Simcoe, Holland and Cook and the invaluable surveying and charting work they did on the upper reaches of the St Lawrence. The charts of Chaleur and Gaspé Bay that they produced were of inestimable importance to Admiral Durell in 1759.53 The ‘three musketeers’ also discovered that existing maps of Newfoundland and the Gulf of St Lawrence were woefully imprecise in latitude and longitude. Together they pored over relevant tomes: Charles Leadbetter's Complete System of Astronomy (1728) and his Young Mathematician's Companion (1739), and presumably many others whose titles escape the ken of history.54 With their minds thus occupied, they doubtless ignored or blotted out Wolfe's daily atrocities. After making the French a farewell present by gutting a sloop and a schooner, Hardy's seven warships returned to Louisbourg, where the main fleet lay at anchor from 2 October to 14 November. Under Admiral Durell the ships then endured five storm-tossed days making the difficult passage to Halifax. Boscawen (legitimately) and Wolfe (illegitimately) returned to England while Amherst stayed in America. It was the mournful fate of the Pembroke to remain in Halifax for the winter.

Halifax in 1758 was an unprepossessing place, perched on a peninsula 4.5 miles wide and two miles long. Founded in 1749 with 2,500 settlers as a counterweight to French Louisbourg, in ten years the town had already attracted immigrants from Scotland, Ireland, Germany and New England. Its main landmark, Citadel Hill, looked down on a dirty, muddy town of log stockades and plank buildings. It was a dark, dank locality, suffused with fog and damp, where the only landscape to gaze out on was rocky scrubland. The streets were rutted tracks, arranged in parallel to the harbour, and the buildings no more than rude huts where the useful trades of a seaport were carried on: ship repairing, dry-docking (for the town acquired a naval dockyard in 1758), carpentry, sailmaking, storekeeping, tending licensed premises and prostitution. The one thing Halifax did have was an excellent harbour, with deep water that never froze over.55 Here the Pembroke's crew were set to work, cleaning, repairing and careening the ship, mending sails and strengthening masts. Inevitably, the boredom of such an existence, with long winter nights given over to drunkenness and brothels, brought in its train a plethora of disciplinary offences. As master, Cook had responsibility for punishment, and his log records the dreary catalogue of offences: fires, started accidentally while the men were lying in a drunken stupor, causing damage to valuable fabrics; disobedience, insubordination and insolence to officers; drunken neglect of duty; stabbings; purloining ship's stores and wine for sale on the black market or barter for other desirables.56

Since the issue of Cook's role as a disciplinarian often surfaces in discussions of his career and personality, it will be as well to place crime and punishment on his ships in a wider context. All sailors on board His Majesty's ships were bound by the Articles of War, which were more draconian in theory than in practice, and in this respect rather like the general ‘Bloody Code’ of eighteenth-century English society, though even the theoretical provisions of the Articles were not as severe as those in the code of domestic land-based law. There were eight offences that were theoretically capital, but in practice only murder and buggery attracted the death penalty. The Royal Navy's attitude to crime and indiscipline was Janus-faced. On the one hand, it was not generally perceived as a major problem, if only because the ruling elite had total confidence in the order and stability of their political system and the rightness of its inegalitarian hierarchy. In any case, very high levels of violence were tolerated in the everyday life of the eighteenth century. Moreover, on land there was an anti-Navy ethos (just as there was also an anti-Army one) which encouraged the prosecution of ship's officers by ordinary seamen. Because of the subtext of hostility from civilian courts, the Admiralty did its best to keep cases beyond their reach.57 On the other hand, when its credibility and legitimacy were challenged, either explicitly or implicitly, the reaction of the Navy could be ferocious. Common punishments were floggings (sometimes ‘around the fleet’) or ‘running the gauntlet’: running between rows of determined chastisers armed with knotted ropes that raised weals and gashes on the body. Twelve lashes justified the time-consuming spectacle of a flogging, and a dozen strokes of the ‘cat’ was usually accepted as the right level of punishment for drunkenness or mutiny. Of course, captains who were harsher disciplinarians often awarded twenty-four or more lashes but did not record the floggings in their log books.58 Apart from murder and buggery, the crimes most severely punished were those that seemed to threaten the comfort, safety or esprit de corps of the ship. This was why, paradoxically, theft was often treated more harshly than desertion or mutiny. A single court on the same ship on the same day sentenced a deserter to 200 lashes, a mutineer to 300 and a thief to 500; there were cases of crews complaining that a thief had received the lenient punishment of ‘only’ 400 lashes. Appeals against floggings were inevitably self-defeating. One sailor who refused a routine flogging and appealed was given 600 lashes by a court-martial. Another who knocked down a midshipman and refused twelve lashes was then given 200 by a court-martial on appeal. It was one of the paradoxes of crime and punishment in the Navy that it was often preferable to be sentenced to death than to a flogging.59 Only one-fifth of those found guilty of desertion in 1755–62 were actually sentenced to death, and only a quarter of those (that is, one-twentieth of those found guilty) were executed, almost always for aggravated offences, such as murder while absent without official leave. It followed that it was in some ways better to gamble with a death sentence, with a high chance of pardon, than to be flogged, for the latter sentence was certain to be carried out.60

Sodomy was regarded with a peculiar horror in the eighteenth century, both as an ‘unchristian’ act not fit to be mentioned in polite company and as an activity detrimental to hierarchy and social order. Life afloat without women inevitably raised sexual frustration to extraordinary heights and, equally inevitably, this deprivation was often ‘solved’ by homosexual behaviour. But it was a dangerous activity, for it was almost impossible to conceal at sea, and buggery was one crime which was highly likely to incur the death penalty.61 Cook was in general relaxed about promiscuous heterosexuality, as he demonstrated later in the Pacific.62 But on homosexuality he shared the prejudices and dislikes of wider society. When one of the crew of the Pembroke attempted sodomy with a messmate, Cook had him flogged where some masters or captains would have opted for capital punishment in terrorem.63 Some critics of Cook, however, claim that both he and Vancouver, also an explorer and officer in the Royal Navy, were more draconian than more legendary floggers such as Lieutenant William Bligh of the Bounty. This rests largely on Cook's record during his last great Pacific voyage, of which we shall say much more later. The first two South Seas voyages do not show him to be a notable disciplinarian. On the Endeavour voyage twenty-one of the eighty-five crew were punished, five of them twice, with a maximum chastisement of 24 lashes and a total over three years of 342 strokes of the cat. On the second voyage (1772–75), just nineteen men were punished, with one sentence of 24 lashes, two of 18, sixteen of 12 and six of 6, making a total of just 288 lashes in three years.64

Yet the winter of 1758–59 was not all boredom suffered and punishment meted out by the master. These were the halcyon days when Cook, Holland and Simcoe pored over maps and charts of the Gulf of St Lawrence and of the great river itself. The legend that Cook in person personally surveyed the St Lawrence river that winter and made an accurate chart of its entire length is pure fantasy – for one thing the river was iced over – but he did collate every scrap of infomation in chart form available. The data assembled during these midnight lucubrations would be of inestimable value when the Navy conveyed Wolfe's army to Quebec in 1759.65 Cook was fascinated by the prospect of being able to record by triangulation every cove, indentation, reef and set of rocks on a coastline and to integrate this with a general relief map. He was well equipped for the task, having a good mathematical background and having improved his knowledge of plain and spherical trigonometry during the second part of 1758 under Simcoe's aegis. Holland added an extra dimension to his skills. He taught Cook all the secrets of his tripod-based table and the telescope mounted on it. By marking headlands and other relief features on drawing paper pinned down on the table and surrounding the telescope, and using an appropriate scale, the observer first collated the angles of observation and then by trigonometry calculated the distances between the different geographical features.66 For Cook this opened up the vista of a really accurate survey of coastlines. He already had the expertise necessary to make accurate hydrographic soundings and to estimate bearings at sea. By marrying Holland's skills with his own, he glimpsed the possibility of coastal surveys accurate far beyond anything yet achieved in Admiralty charts. Further refinements were later added, including the use of sextants, theodolites and a measuring rod known as a Gunter's Chain. Cook was already well on his way to becoming a master surveyor as well as a master navigator.67 Already we can discern one skein in Cook's nautical genius: he was, so to speak, a Renaissance Man of the oceans. Polymath and versatile all-rounder of the seven seas, he crossed over barriers most sailors never crossed. For example, mariners were usually either deepwater or coastal specialists, but Cook was both. As his great admirer John Beaglehole has written: ‘He who had grounded in the Esk could ground in the Endeavour River. … The man who mastered the Barrier Reef was the man who made the great oceanic sweeps of the second voyage; the man who charted New Zealand was the man who went down to Latitude 71 South.’68

The Halifax winter gradually released its icy grip. It should be remembered that these waters are cold even in summer: in June 1755, off Cape Breton Island, Boscawen noted that he and all his men had chilblains from the cold. Not surprisingly, many men marooned in these latitudes in the winter of 1758–59 died of frostbite, for winter work even in the harbour was dangerous and much of it impossible, since the running ropes froze in the blocks and the sails were stiff with ice and snow, ‘like sheets of iron’. The men complained that they could not expose their hands long enough to the cold to do their duty aloft, so that the topsails could not be handled.69 Admiral Durell was accused of inactivity, laziness and lack of enterprise in not attempting to move into the St Lawrence before the main fleet returned from Britain, but much of the criticism came from Wolfe, a man woefully ignorant of the reality of the sea and seafaring, and even of the elements, though he complained loudly enough when he himself was the victim of seasickness.70 Harsh even by normal standards, the winter of 1759 saw sailors in nearby Louisbourg amusing themselves by jumping from ice floe to ice floe in the harbour. Almost the only beneficiaries of the cruel weather were the French, who were able to run the supposed blockade by the Royal Navy at Halifax and Louisbourg in their fast navires de flute, stripped of all guns, carrying only supplies and thus able to bring to Montcalm and the defenders at Quebec not just food supplies and ammunition but the unwelcome news that the British were preparing a massive effort to take Quebec.71

Massive the enterprise certainly was. In addition to Durell's squadron of ten ships of the line and four frigates already at Halifax, Pitt assigned a further fourteen warships, six frigates, three bomb-vessels and three fireships to accompany a further 12,000 redcoats, to be commanded by Wolfe. The plan for 1759 was that Amherst would complete the conquest of the French wilderness strongholds in Canada and, if successful, would proceed to Montreal and then Quebec to assist Wolfe, who would meanwhile approach up the St Lawrence with an independent command. Wolfe's promotion was surprising, given his previous insubordination and some eccentric behaviour while home on leave during 1758–59, but he retained the confidence of Ligonier, whom Pitt did not wish to override. Even Ligonier, though, drew the line when Wolfe asked to be assigned to duties and insisted he had to return to the New World in the spring of 1759. This, as it turned out, was to be Britain's annus mirabilis, when she decisively defeated France in India, the West Indies, Germany and North America as well as scoring two knockout naval victories over her ancient enemy.72 Naturally, none of the contemporary participants could have envisaged such an outcome. Boscawen, the steadying influence of 1758, was assigned to duties in the Mediterranean, and would win the memorable victory of Lagos in July. Commanding the fleet this time was Vice-Admiral Charles Saunders, hand-picked as the least primadonnaish of old salts and therefore unlikely to inflame Wolfe. A highly versatile individual, Saunders had been round the world with Admiral Anson on his epic circumnavigation, was a permanent protégé of Anson's and with his help climbed the ladder eventually to become First Lord of the Admiralty. He was also MP for Hedon in Yorkshire, had his portrait painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds and was himself a talented artist who produced a famous painting on the death of Montcalm. He was one of those men who was good enough to rest content on his merits and did not need to prove anything. Even the acidulous Horace Walpole, who rarely had a good word for anyone, claimed that ‘No man said less or deserved more.’73

On 17 February Wolfe and Saunders sailed from Portsmouth and endured another rough passage across the Atlantic, with the ocean again at its winter worst. After two months of pitching and rolling, the intrepid Saunders found himself confronted on 21 April by a sea of ice. For a week he tried to get through this, failed, then changed tack from Louisbourg to Halifax, where he anchored on 30 April. With his dislike of the Navy, Wolfe immediately found fault with Durell for not having already started up the St Lawrence. The verdict of historians since, and the Admiralty then, was against Wolfe, for Durell had been promoted to rear admiral of the Blue while at Louisbourg and further promoted to rear admiral of the Red in February 1759.74 Goaded and chivvied by Saunders, Durell finally cleared from Halifax on 5 May as part of an advance reconnoitring party, of which the newly furbished Pembroke was part. Their initial task was to provide a credible chart and sailing directions from Louisbourg as far as Bic, the first part of the 400-mile estuary of the St Lawrence. Cook had already been through the Cabot Strait and the Gulf of St Lawrence as far as Gaspé; beyond that were 200 miles of deep water and secure sailing to the small islands of Bic and Barnaby.75 At first the thirteen ship convoy sailed through what seemed like schools of loose ice – the first time Cook had observed the phenomenon. Personal tragedy struck Cook almost at once for, off Anticosti Island on 16 May, his great friend Captain Simcoe, who had been ill with pneumonia, died and was committed to the deep after a 20-gun salute. Cook recorded the great loss in the log with an almost stoic resignation.76 The new captain, John Wheelock, transferred from the Squirrel, was a shadowy figure who made no impact on Cook.77

The French had long regarded the St Lawrence as their first line of defence. Moreover, they had learned valuable lessons from the two abortive British attempts on Quebec, in 1690 and 1711, the second of which was essentially defeated by the river itself. Montcalm had laid first-rate contingency plans to deal with any British riverine invasion, and these included the placing of batteries at Gaspé, the Ile-aux-Coudres, Cape Tourmente, the Ile d'Orléans and, Pointe-Lévy (Point Levis) as well as blocking the narrow channel known as the Traverse by sinking ten blockships in it. Because of financial shortages, lack of manpower and the long-running dispute with Vaudreuil, however, none of these eminently sensible measures was adopted. Montcalm was reduced to having his weapon of last resort deployed as the very first one, for he intended to use fireships against any British men-o'-war who got through to the confined spaces below Quebec.78 This meant that Durell had a trouble-free passage up to Barnaby island, where he anchored on 20 May. Now he demonstrated how fatuous Wolfe's criticism of him for being idle and over-cautious was by exceeding his orders and pressing on upriver. He left a few ships at Bic for liaison and held on for the Ile-aux-Coudres with the majority, including the Pembroke. Whereas up to Bic the only real shipping hazard was the coastline and the few islands with shoals, beyond Barnaby Island the St Lawrence was notoriously intricate. The north shore was a maze of shoals and rocks where the Sanguenay River fed into the mainstream, and then came a labyrinth of islets, reefs, shoals and bars, all tricked out with tides, eccentric currents, eddies and stretches of rapids which had to be carefully bypassed. Two-thirds of the way to Quebec from Bic came the Ile-aux-Coudres, with a narrow channel separating it from the north shore and the broad stretch of the St Lawrence to its south. Capturing three supply ships en route, Durell learned to his consternation that Montcalm had not only been able to send an envoy to France in late 1758 to request reinforcements and new orders but that the man sent, the future Pacific explorer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, had actually been to Versailles, received orders and made good his return though, sadly for Montcalm, without accompanying troops.79 In a spirit of pique Durell gulled a number of French river pilots, enticing them aboard by flying false (French) colours.

At the Ile-aux-Coudres Durell landed some troops but found it unoccupied. Emboldened by this, he sent his ships even farther south-west towards Quebec, as far as the Ile d'Orléans, also close to the north shore, overlooked by the high, forested Cap Tourmente where Montcalm had wanted to site a battery. The captured French pilots were pressed into service and given to understand that any navigational errors arising from their advice would be regarded as sabotage and punished accordingly. The passage from the Ile-aux-Coudres to the Ile d'Orléans was also supremely perilous, being a maze of islets.80 Thinking a landing on the Ile d'Orléans, which was within sight of Beauport and the Montmorency river would surely be contested, Durell sent as escorts for his troop transports four men-o'-war including the Pembroke and Squirrel. When this island also turned out to be deserted, the French having pulled back to their defensive inner perimeter in the environs of Quebec, Durell ordered the advance party into a stretch of water known as the Traverse. Whereas hitherto there had been narrow passages between the major islands and the north shore but a broad span of the St Lawrence to the south, at the Ile d'Orléans the river narrowed alarmingly into the south channel at the foot of the island. Even to reach the south channel from Cap Tourmente, one had to make a diagonal crossing over the Traverse, notoriously treacherous and difficult to navigate, full of shifting tides and unpredictable currents.81 The French had never brought large vessels this far up the river, and no adequate charts existed; local pilots knew the way through with the aid of buoys and markers but, in the one sensible defensive measure Montcalm had been able to implement, these had all been removed. All of Cook's skill and expertise gained on the North Sea coast were now required. On 8 June he and the other three masters commenced a via dolorosa by water, proceeding with agonising slowness, sounding and marking the passage. For two days the wearisome chore continued, but Cook and his colleagues were so successful that they found not just the old route used by the French pilots but a secondary one as well. They then withdrew to inform Durell; Cook in his usual laconic matter recorded a great triumph in his log in his customary throwaway style.82

Once Cook and his fellow masters had made straight the ways, the task of Durell and Saunders was relatively straightforward. Wolfe, Saunders and the main fleet left Louisbourg on 4 June and made slow but steady progress up the Gulf of St Lawrence and into the estuary. The Navy's lead division passed through the Traverse safely on 25 June, with the ship's boats acting as buoys.83 To Montcalm's consternation the British had penetrated his first line of defence as if they were swatting away a fly. Naturally, as always, success has a hundred parents, and the heroic efforts of Cook and his comrades were soon being depreciated. The master of the transport ship Goodwill boasted that he had not needed Cook's reconnaisance or the boats acting as markers and declared: ‘Damn me if there are not a thousand places in the Thames more hazardous than this.’84 By the 27th all the ships were safely through, and the whole fleet anchored in the Quebec basin between the tip of the Ile d'Orléans and Point Levis. But the odds turned suddenly in favour of the apprehensive French the following day, for a terrible storm destroyed many of the boats and drove many of the transports ashore. Taking advantage of the confusion, Montcalm launched his fireships against the enemy fleet, but the French ignited them prematurely, allowing the British to evade them or tow them clear.85 Wolfe then seized the initiative. His troops captured Pointe-Lévy on 29 June, and landed east of the Montmorency Falls on 9 July. He then commenced the first of his many controversial acts of brutality during the siege by the remorseless shelling of Quebec, regardless of the presence of civilians. What Cook really thought of Wolfe we will never know, but doubtless their mutual friend Samuel Holland encouraged a positive opinion. Holland was by this time so deeply in Wolfe's counsels that the general took him as his aide on a reconnaissance of the south bank of the St Lawrence.86

Cook and the Pembroke spent most of July inactive; the ship was anchored off Point Levis. But suddenly, on the night of 18 July, there was a brief upsurge of naval fighting. The trigger was Wolfe's habitual impatience with the Navy. Like Napoleon later, Wolfe knew nothing whatever about seas, rivers and seamanship. Almost criminally ignorant of the problems of pushing upriver beyond Quebec – principally that strong ebb tides ran for eight hours a day and that there was a contrary wind from the west – he attributed all delays by the fleet to timidity, defeatism or incompetence. Finally the Navy achieved the near-impossible and thus made Wolfe's ultimate success possible – but then predictably were written out of the victory script. The French had long been convinced that it was impossible for large ships to pass through the narrows under Quebec's guns and into the upper St Lawrence, but on the evening of the 18th the frigate Diana, with six other vessels, made the attempt. While her comrades got through, the Diana ran aground and the Richmond was sent to her aid. As often happens, a small engagement soon escalated into a larger one and the Richmond in turn was in trouble, under attack from French cutters. The much more formidable Pembroke made short work of these intruders with her big guns.87 Meanwhile Wolfe was getting nowhere with his multi-point probing skirmishing and shelling. At the end of the month he shifted his attention from the upper river and decided on an attack on the French position at Beauport near the Montmorency Falls. Cook in person advised Wolfe that the two redoubts on the extreme right of the Beauport shore could be seized, since a ‘cat’ could get close enough to provide covering fire of a withering type.88 Two of them were to be run aground at high tide with commandos, a hundred yards from the first redoubt; the disembarked troops would then capture the first objective. Once again ‘mission creep’ manifested itself. The initial commando attack failed, then more and more troops were committed to the assault. Even so, the assault was a disastrous failure: the British sustained 440 casualties against sixty French dead and wounded. There were several blunders, which enabled the various players to blame-shift with gusto after the event. Cook's calculations were far too optimistic, and the cats grounded too far out, so that the firepower covering the landing was inadequate. On the other hand Wolfe changed his plans and landed at low water, far too close to the French entrenchments.89

The Pembroke, after its dramatic nocturnal excursion on 18–19 July, continued to ride at anchor at Port Levis and would remain there until 19 September. But its master was out and about on various energetic pursuits and on one of these came close to capture. He was out on the river near the Ile d'Orléans when a party of Montcalm's Indians (tribe unmentioned) tried to cut him off from the shore. He made the shore just ahead of his pursuers, who were then driven off by Wolfe's men on the island.90 Yet if Cook had had a narrow escape, Wolfe's fortunes were even sunnier. For a while it looked as though 1759 was going to be ultimately as unsuccessful as 1758. Although Montcalm and his men were short of food, if they could just hold out until the end of September, ice and the threat of being trapped in Canada for the winter would force Wolfe's mighty armada to set its sails for home. Wolfe ‘s chances seemed very slender, even though he was buoyed up in the days immediately after the Beauport/Montmorency disaster by the welcome news that Amherst had scored a series of victories: at Ticonderoga, Crown Point and Niagara.91 With the Iroquois now decisively on the British side, the battle for the interior seemed won; only Quebec and Montreal continued defiant. Yet Wolfe left his decisive move until the last possible moment. During August he seemed to have no master idea except the brutal scorched-earth devastation he practised in the environs of Quebec. Suddenly, however, he pulled his masterstroke of landing on the north shore in darkness at the Anse au Foulon, clambering up by a secret path to the Heights of Abraham and then defeating Montcalm outside Quebec (12–13 September). The death of both commanders in battle seemed to place them for a while beyond criticism. Whether the landing at Anse au Foulon really was Wolfe's own idea, as he claimed (Samuel Holland backed him up, though this is what one expects from a friend) or whether the track leading up to the Heights of Abraham was really divulged to him by Robert Stobo, is a matter that lies outside the purview of a biography of James Cook.92

Cook was involved in this decisive denouement in two ways. The attack via the Anse au Foulon required very precise knowledge of the onset of the ebb current on the night of 12–13 September and the position of the moon. Since Cook was the man who probably knew more about the St Lawrence tidal patterns than anyone else in the fleet, we can be reasonably certain that Wolfe consulted him.93 Moreover, Cook was involved in the elaborate feint carried out that night at Beauport, scene of Wolfe ‘s previous failure, when the British attempted to convince the French that their commander was coming back for a second attempt. On the 11th Admiral Saunders ordered his men to place buoys off Beauport, pretending to mark obstacles for the assault craft to avoid. On the 12th he surpassed this with a very ostentatious coup de théâtre. Every last rowing boat in the fleet was assembled for a showy flotilla seen to be making its way across the river to the Montmorency Falls, together with the clangorous clamour of matelots seemingly aping the methods of beaters on a tiger-shoot.94 Montcalm took the bait and concentrated his forces at Montmorency. Only in the small hours of the morning did a signal come from Quebec to announce the ‘incredible’ news that Wolfe was even then debouching on to the Plains of Abraham. However, Wolfe ‘s victory was not the blazing triumph it has sometimes been said to have been. He died before the second part of his plan could be implented, which involved trapping Montcalm's remaining troops at Montmorency; these escaped to fight another day. Yet Wolfe in his death won immortal fame and in this prefigured by twenty years the fate of the master of the Pembroke who had so valuably advised him.

Quebec did not surrender immediately. Indeed, once again the Navy can be seen as the key actor for it was only when Admiral Saunders brought his best seven battleships into the Basin and prepared to blow the lower town apart with devastating broadsides that the city's commandant, Chevalier de Ramezay, decided he had had enough.95 The perfectly natural joy Cook felt at the fall of Quebec may have been tempered by sentimental regret when, five days later, at Saunders's command, he was transferred as master to the Northumberland, a 70-gun man-o'-war with a crew of 500.96 Although the new ship's captain was Alexander Lord Colville, a second appointment as captain was made in the shape of one William Adams, another shadowy figure in the Cook biography.97 It has been speculated that Saunders intended to have Colville promoted to commodore and that he was therefore ‘phasing in’ a new commander. Although he had a new ship, in many ways Cook had to languish as before, for once again he was to spend a long winter in Halifax, essentially five more months of boredom, study and punishing refractory sailors; at least conditions in Nova Scotia were better than those faced by the luckless British garrison in Quebec. Saunders, with most of the fleet, returned to England, where he later noted Cook's outstanding charts and drew them to the attention of the Admiralty.98 Left behind in Halifax were five ships of the line, three frigates and some sloops. Though he did not know it, Cook had seen the last of battles with a European enemy. Although there would be shots fired in anger in the future, never again would the Northumberland's talented master have to face a broadside from the big guns of France, the ancient foe of England. From now on the real enemy would always be the cruel, implacable ocean.