THE famous dinner party at which Cook definitely accepted command of the the third expedition can be seen in retrospect as the first scene in the first act of an unfolding tragedy. As Beaglehole remarks tersely: ‘The dinner party was a great success, a triumph of management. It was a disaster.’1 It is important to probe Cook's state of mind and his motivations when he set out on the quest for the Northwest Passage. A few days after the dinner Cook wrote to his old friend Captain John Walker in Whitby:

I expect to be able to sail about the latter end of April … I know not what your opinion may be on this step I have taken. It is certain I have quitted an easy retirement for an active and perhaps dangerous voyage. My present disposition is more favourable to the latter than the former, and I embark on as fair a prospect as I can wish. If I am fortunate enough to get safe home, there's no doubt but it will be greatly to my advantage.2

Here we have a clear statement that he detested retirement and would rather face danger than idleness. Cook was in that class of great achievers who must have work and reputation, or in his case constant voyages of discovery. ‘To my advantage’ clearly referred to the long-standing reward of £20,000 offered by the British government to any navigator who would find the Northwest Passage.3 With such a sum, perhaps roughly equivalent to £1 million in today's money, he could finally become a rich landowner, enter the ranks of the aristocracy and thus surmount the seemingly ineluctable barrier of class. Life was tough even for the most talented meritocrat in the eighteenth century; Cook had already come far but, as an almost chillingly ambitious man, he wanted to break through the ceiling that separated mere achievers from the possessors of vast inherited fortunes. A triumphant third return would almost certainly bring further rewards, in the shape of a huge bounty for his maps and charts, accelerated promotion to admiral, and very probably a knighthood. Cook could thus simultaneously climb the ladder of honours and that of finance. It is likely that other considerations weighed as well. If Clerke or some other navigator commanded the expedition and found the Passage, would that not eclipse his own achievements to date, so that he would come to seem a mere John the Baptist to a greater Messiah? Cook's psychology was also important. As a ‘control freak’ he was not suited to life on land, where he was beset by rivals, critics and Admiralty committees. At sea he was the supreme autocrat and dictator whose word was law and whose mere nod could indicate punishment or reprieve.4

Deeper than this into Cook's mind we cannot go, for lack of evidence. In his case, more than with almost any other ‘great man’, the person effectively was the role. As one commentator has put it: ‘there were depths; but the soundings are few’.5 Psychoanalytical investigations of historical figures are always fraught with peril, but in Cook's case they are simply impossible, for we know almost nothing of his childhood and his relations with his parents or with his wife and his own children.6 A deeply secretive person, as are many great achievers who have risen from lowly origins (again the comparison with H. M. Stanley is instructive), Cook almost never allows the mask of seagoing professional, a kind of navigational machine, to slip; the fact that his wife burned all his personal correspondence completes the cordon sanitaire he managed to throw around his personal life. Of course the fact that one's wife burns all correspondence does not necessarily preclude a biographical approach via depth psychology, as the notable example of the explorer Sir Richard Burton shows, but in Burton's case there was a wealth of published writings available, in which he frequently gave important clues to the workings of his psyche.7 Cook's writing by contrast was almost entirely about his profession and his career. What can be said quite confidently and without fear of contradiction is that Cook by the time of his third voyage had undergone a personality change. To account for this convincingly, we need hard data not fanciful conjecture, but this is not available.8 If Cook suffered from intestinal obstruction, roundworm infection and consequent vitamin B deficiency – producing fatigue, constipation, irritability, loss of initiative and depression – or if, as seems probable, he was treated with opiates for sciatica and gradually became dependent on the drug, this could easily explain the marked change noted by everyone who had sailed with him before. To anticipate the narrative for a moment, the old Cook of the second voyage would not have expressed lack of interest when hearing about the Samoan and Fijian islands on Tonga but would have sought them out. Similarly the surveying genius who charted New Zealand would not have become confused in the Bering Sea and identified the same island as three different ones.9

Listless and passive as Cook so often was on the third voyage, he clearly suffered from depressive interludes. Many theories can be advanced to explain this, going beyond the explanation of organic physical illness. It is sometimes alleged that he felt peculiarly ‘alienated’ on his final voyage because this time he had no one to confide in, since the educated men on his ship (such as James King) were much younger and inferior in rank, and may well have been intimidated by his aura, charisma, gravitas or simply the weight of his fame. If objective illness or mood swings caused his integrated ego to fracture, that would explain why he was no longer solely the careful, meticulous technician, obsessed with control and order, but sometimes launched into erratic enterprises, revealing the mentality of a gambler. The mania for precision and mathematical objectivity began to coexist with an equal and opposite penchant for taking chances and defying the odds – exactly the psychological syndrome we observe in the case of Napoleon.10 Sour, irascible and increasingly autocratic, Cook unhappily collided with a crew more disposed than those of the Endeavour or the Resolution to question his authority. One can guess at the many sources of stress. As he grows older a man obsessed with control is likely to find the sheer contingency of the world and its stubborn and irreducible nature intolerable, which in turn generates impatience and tantrums, all observed on the Resolution–Discovery trip. Unconsciously he may have guessed that the Northwest Passage would turn out to be a chimera and that he was engaged on a fool's errand. He was deeply irritated and indeed angry that he had been sent out with an inadequate flagship and that, because of the incompetence of the authorities at Deptford dockyard, the Resolution was never the ship she had been on the second voyage.11 It is unlikely that he had become bored with navigation but he may have become disillusioned with exploration, and at a number of different levels. The most ingenious suggestion is that the ‘fatal impact’ of Europeans on Polynesia may have worked the other way and, to use psychoanalytical language, that his unconscious was disturbed by a dangerously contagious and pagan view of happiness he had brought back from the South Seas; to use Jungian terms, his unconscious may have suffered psychic harm as ‘compensation’ for his conscious refusal to avail himself of the free sexuality on the islands.12 Finally, and most obviously, Cook was simply too old to command a voyage of exploration. At 48, after six years of virtually non-stop stress conquering the oceans, he had been at sea too long and was exhausted. Normally, 40 was considered an advanced age for a sea captain and those still at sea at this age usually thought themselves hard done by.13 Beaglehole sums up the situation judiciously: ‘We have a man tired, not physically in any observable way, but with that almost imperceptible blunting of the brain that makes him, under a light searching enough, a perceptibly rather different man. His apprehensions as a discoverer were not so constantly fine as they had been; his understanding of other minds was not so ready or sympathetic.’14

All this lay in the future in the last week of June 1776 when a seemingly jaunty Cook wrote to his old friend Commodore Wilson at Great Ayton: ‘If I am not so fortunate to make my passage home by the North Pole, I hope at least to determine whether it is practicable or not. From what we yet know, the attempt must be hazardous, and must be made with great caution.’15 The truly interesting thing is that Cook genuinely thought he could sail to the North Pole, and was still fixated on the old orthodoxy that, since seawater did not freeze, the Arctic Ocean must be ice-free.16 He was obviously preoccupied, doubtless mixing practical concerns with more deep-seated mental revolutions concerning his aims and motives. The motivations of the nation state that sent him out were also being questioned; the time was long gone when Sandwich could brush aside French queries on the purpose of the Cook voyages, as he had done in 1772 by saying that the British government was actuated purely by curiosity about the world.17 Russia, Spain, France and even the rebellious American colonists were deeply suspicious about the true objectives of the Resolution–Discovery venture. The Bourbon powers learned that Russian cooperation in the Bering Strait was being counted on and leapt to the wild deduction that the British were linking up with the Russians in Kamchatka as the prelude to a full-scale invasion of Japan, in self-imposed isolation from the world for the past one hundred and fifty years.18 Spain was particularly suspicious of Cook and issued empire-wide orders that if he called at any of their ports in the Americas, he was to be arrested.19 The American colonists were more far-sighted. Convinced that the interests of science were the true goal of the expedition, Benjamin Franklin persuaded his confrères in the American Congress that all possible assitance should be rendered to Cook.20 After some hesitation, France followed suit: Louis XVI ordered that if French ships encountered Cook they were to leave him alone, as he was engaged in the important task of bringing light to benighted savages.21

Early in June the two ships were ordered round to Plymouth for the final ‘jump-off’, but there were delays, long enough for Sandwich, Palliser and other Admiralty bigwigs to attend a final ‘noble dinner’ on the Resolution. Sandwich told Cook he would be paying Cook's wife Elizabeth an extra pension while he was away so that she would want for nothing material.22 Since Clerke was still detained in King's Bench prison, it fell to James Burney to take the Discovery round to Plymouth, to the intense pride of his family. On 23 June Cook made his final farewells to Elizabeth, who presumably bore the parting with a stoicism that was by now second nature. He picked up Omai in London at 6 a.m. on the 24th and together they sped to the Nore, arriving in Chatham at 10.30. By now both Sandwich and King George were desperate to see the back of Omai. What had been amusing at first had rapidly become tiresome, especially as Omai was now going in for heavy flirtations with society ladies and irritating the aristocracy with his presumption. His essential clown-like status was well conveyed by Fanny Burney in reporting a social occasion, when all Omai could find to say about whoever was mentioned was that he was ‘very dood man’.23 On 25 June Cook sailed the Resolution to Plymouth to rendezvous with Burney who had already been there three days. Plans were afoot to help Clerke break out of jail, but these had to be matured. Cook therefore instructed Burney to wait until Clerke made his appearance, presumably with the Bow Street Runners in hot pursuit, and then follow him down to Cape Town. To assist morale, once again two months' wages were paid in advance.24 In Plymouth he found the town in a hubbub, with press gangs everywhere and ships being fitted out for the American war to convey Hessian mercenaries there. The very first official account of the voyage (in 1784) would point to the irony of Cook trying to explore the north-west coast of North America for Britain at the very moment the American colonists were in revolt against Britain.25 As a farewell present he was informed that the Royal Society had awarded him its prize medal for his contributions to seamen's health. He cleared for the Cape on 12 July, only to discover almost immediately that the caulking of the Resolution had been defective and that the ship was leaking; rain flooded into the officers' cabins and soaked into the storerooms and sailrooms, threatening destruction to everything that was needed for the voyage.26 A superstitious man, which Cook was not, would have read this as an extremely bad omen.

Cook passed Ushant and by 24 July was off Cape Finisterre. He anchored at Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands on 1 August.27 Here Cook bought fodder for the animals and provisions for his seamen, including bullocks, pumpkins, onions, potatoes and a huge quantity of wine at a knockdown price. He made some friendly contacts with French and Spanish sea captains who were interested in his chronometer, but most of the others on the Resolution did not enjoy the three-day stay on Tenerife. Omai found the Spanish as hostile as the people of Bora Bora would have been to a Raiatean, while Samwell, the Irish surgeon's mate, thought the locals a set of narrow priest-ridden bigots.28 As they left the Canaries, one of the seamen was given six lashes for neglect of duty. It is unclear whether the poor quality of the sailors or a mistake by one of the officers, Bligh perhaps, or even Cook himself, was responsible for the next worrying incident, when the Resolution nearly ran on to the rocks off Bonavista and a violent emergency hard-a-starboard manoeuvre was ordered before the ship narrowly missed the reef.29 Together, the two incidents might have revealed to the proverbial Martian observer that there was already something very wrong with this third voyage. The bad omens continued after Cook made a brief call at the Cape Verde islands to stock up on provender for the animals. Immediately on leaving these islands they were assailed by heavy rains, which still further exposed the extent to which the Resolution was leaking because of the incompetent or corrupt caulking at Deptford.30 Cook continued making south until he was about at latitude 5N, then swung out with south-east trades in a wide arc towards the coast of Brazil, intending to come in to Cape Town from the west; this was common practice in the sailing ships of the time. Cook, a traditionalist, encouraged the rough horseplay of the Crossing the Line ceremony, which younger captains were increasingly discouraging. Bligh was surprised to find that most men chose to be ducked rather than pay the forfeit of a bottle of rum. Following behind in the Discovery, Clerke showed himself to be one of the newer breed of commanders by bribing his men with grog not to perform the ceremony.31

Cook put in to Cape Town on 18 October, having shaved twelve days off his previous time from England to the Cape, even though they were in stormy weather most of the time; the crew might have been deficient as seamen but they were evidently good fishermen, to judge from the number of sharks and dolphins hauled aboard once they were in the South Atlantic.32 Cook was received with a high respect that came close to idolatry, and Samwell was amazed to find that Cook seemed even more famous in South Africa than he was in England.33 This was Cook's fourth time in Cape Town and Dutch officialdom could not have been more helpful. He set his caulkers, sailmakers and coopers to work on repairing and refitting the Resolution while he waited for the arrival of the Discovery which was about three weeks behind. The local people, however, treated Cook and his crew with more cynicism than the Dutch bureaucrats. Cook landed all his livestock to graze but some local ‘entrepreneurs’, coveting the flocks of sheep, deliberately set a large and savage dog among them, which killed a number of sheep and dispersed the rest. Cook protested to the governor and claimed reparation, but this individual at first claimed that the Cape Colony was crime-free. Even when he set his police on the case, they could come up with nothing, so in the end Cook employed a group of low-life ‘grasses’ and ‘narks’ to track down the sheep and in this way discovered the villains and recovered his livestock. Thus warned of the temperament and attitude of the proletarian locals, Cook reluctantly herded all his cattle and sheep back into the cramped quarters of the Resolution.34 It was not only the Boers who gave trouble. His men, off the leash on shore leave, committed various offences, including selling some of their winter gear and other necessities of the voyage. No fewer than nine of them felt the lash for this indiscipline. That they were sailing under a new and more intolerant Cook is obvious from one striking statistic. Only just over four months from England, Cook had already meted out a full third of the total lashes he had given as punishment on the entire voyage of 1772–75.35

To Cook's immense relief the Discovery arrived on 10 November. Clerke had encountered the most sustained spell of stormy weather in his career so far on his way south, being continually mauled by a ‘large western sea’ on his run to the Cape; his survival was a close-run thing. There was a giant swell from the south, maybe 50–60 feet high, ‘so much so as to make our bark plunge exceedingly. I am obliged to keep the reefs in the topsails on that account; it is a most unfortunate swell as it very much impedes our southing and drives us to the eastward.’36 The same storms and gales tore to pieces the tents Cook had erected on the shore, damaged the astronomical quadrant and battered the Resolution as she lay at anchor in Table Bay, but Cook was proud of her as she ‘was the only one that rode out the gale without dragging her anchors’.37 Cook's spirits lifted with Clerke's arrival, and Clerke too seemed suitably cheerful, as is evident from his letter to Banks: ‘Here I am hard and fast moored alongside my old friend Captain Cook so that our battles with the Israelites [his creditors and the bailiffs] cannot now have any ill effect upon our intended attack upon the North Pole.’38 Cook sent his caulkers to work on the Discovery and then became involved in a furious altercation with the local bakers. Cook had placed a huge order for bread for the Discovery, intending to clear from the Cape at the earliest possible moment after Clerke arrived (this was before he was aware of the extensive storm damage the sister ship had sustained). It now turned out that the bakers had not even started on this order. They claimed a shortage of flour, but the truth was that they had not been willing to start work until the Discovery actually arrived; they feared that if Clerke's ship was lost at sea, Cook would simply cancel the order.39 It turned out that there was time to send out an inland exploring expedition, whose principals were Gore, Omai and the surgeon William Anderson. Meanwhile Cook bought more animals to add to his menagerie: two young bulls, two heifers, two colts, two mares, two rams, several ewes and goats, rabbits and poultry and even some monkeys – all supposedly destined for New Zealand and Tahiti.40 Here we see further signs of Cook's lack of grip. He should have made allowances for the full implications of his Noah's Ark – not just in terms of the vastly increased need for water and animal fodder and the likelihood that the beasts would not survive in the Antarctic conditions on the way to Kerguelen, but with regard to the vast amount of animal excrement that would be generated and which conflicted with his hitherto fanatical concern with hygiene. The travelling zoo seems just one more piece of evidence pointing to an increasingly erratic personality.

Cook sailed from Cape Town on 30 November, setting a course south-east in search, first, of the Prince Edward and Crozet islands, using the chart Crozet had given him in 1775. He was sailing into some of the stormiest waters in the world and for nearly two weeks the Resolution and Discovery suffered grievously, pitching and rolling in high seas and mountainous waves. Cook was afraid his seamen might not be up to the severest challenges of these ultra-testing conditions. His particular fear was that a helmsman might panic as a giant wave aft caught up with the ship, causing him to swing round broadside and thus ‘broach to’, offering the ship as a target and making almost sure she would be engulfed or overwhelmed. Even if the seamen maintained cast-iron discipline, there were still dangers; on 5 December a white squall carried away the mizzen topmast. Cook described his melancholy mood on the pelagic via crucis to the south-east:

We continued our course … with a very strong gale from the westward, followed by a very high sea which made the ship roll and tumble exceedingly and gave us a great deal of trouble to preserve the cattle we had on board, and notwithstanding all our care several goats, especially the males, died and some sheep, owing in a great measure to the cold which we began now most sensibly to feel.41

At last, on 12 December he sighted and sailed between the first of the islands mentioned by Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne and named them Marion and Prince Edward Island (the two are now called Prince Edward Islands). He then held on to the south-east for Kerguelen, passing the Crozet islands, still confident that he would find the big island discovered by the eponymous French navigator while admitting that the navigation was ‘both tedious and dangerous’.42 That was the bluff Cook's usual understatement when it came to sea states. The high seas and mountainous waves continued, with the sea frequently breaching over the ship.43 Cook was now in the ‘Atlantic convergence’, where upwelling cold water from the Antarctic fights with the warmer waters of the Indian Ocean. The result is persistently high winds, routinely generating 40-foot waves; crests of 50 feet are common and those of 60 feet and above by no means rare.

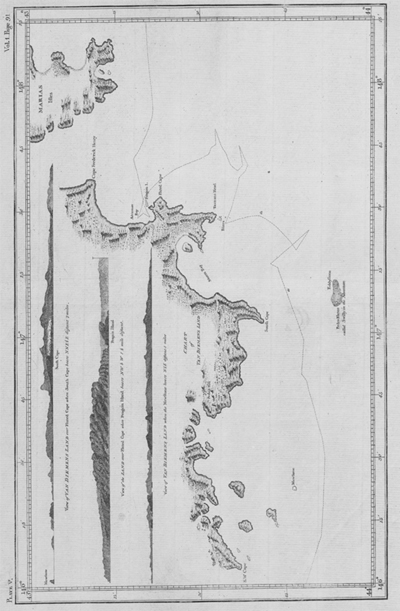

By 21 December a thick fog with nil visibility added to the dangers; the two ships kept in touch only by the frequent firing of their guns. Both Cook and King entered in their logs the concern that if they hove to they would lose valuable time but, if they sailed on through the fog, they might miss Kerguelen altogether. On 24 December Cook, however, found the main island in the Kerguelen group, exactly where he thought it would be. He anchored in what he called Christmas Harbour (Baie de l'Oiseau) and sent out parties to climb hills and reconnoitre. The Kerguelen archipelago consists of over 300 islands and islets between latitude 48"30"–49"45S and longitude 68"40" and 70"30", perhaps only a dozen of any real size or importance, and all of them, like the Prince Edwards and the Crozets, volcanic.44 The main island (La Grande Terre), 95 miles from east to west and 75 miles north to south, is a mass of rocky, treeless hills, bogs, sounds, inlets and minor bays, with mammal life restricted to seals, especially the elephant variety. It is a paradise for Antarctic birds, boasting thirty species, including the Rockhopper, Macaroni, Gentoo and King penguins, albatrosses, skuas, giant petrels, sheathbills and terns and, because it is the only sizeable land in the southern Indian Ocean, would, after du Fresne's and Cook's visits, become a magnet for polar explorers and whalers.45 Cook was delighted to send his hunters out on a killing spree that would replenish the larder with penguins, flying birds and seals. He gave his crew furlough on Christmas Day and brought back a bottle with Latin inscriptions written on parchment in its neck, testifying to the French visits to the island in 1772, 1773 and 1774. Since the other side of the parchment was blank, Cook added his own Latin inscription and dated it December 1776. He climbed a hill to get a view of the coast on 28 December and then spent two days on a running survey, passing along the north coast of Grande Terre, then down the west coast and finally halfway back up along the east coast before at last standing away on 30 December, heading for Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania).46 The bad weather tracked them remorselessly. For a week there was thick fog, which created an impression of unending darkness, then high seas and, on 17 January, a squall so violent that the Resolution's fore-topmast and the main topgallant mast were destroyed. The tangle of rigging prevented them from being swept overboard, and Cook also had a spare topmast, but the devastation and wreckage was such that the crew had to spend an entire day in repairs, and even then the topgallant mast could not be replaced. By now some alien cynics were even questioning Cook's judgement and seamanship. In pursuit of what seemed a quite arbitrary timetable Cook, thought King, had been crowding on too much sail for the prevailing conditions.47

Van Diemen's Land (the Tasmanian coast) was sighted on 24 January 1777 and on the evening of the 26th Cook anchored in Adventure Bay, where Tasman had been in 1642 and Furneaux in 1773. On the morning of 27 January Cook sent King in command of two separate parties, one cutting wood, the other grass for the animals; wary of the locals he also sent along a detachment of marines to guard the detail. It was the profusion of poisonous snakes, rather than hostile aborigines, that most concerned the foragers, for on New Zealand and the Pacific Islands such serpents were unknown. Somehow these brave guardians of their comrades managed to smuggle drink on to the boats to take ashore and then got horribly drunk. Five of these men were carried back to the Resolution in a stupor and hoisted up the side. All were flogged next day, the ordinary participants with twelve lashes and the ‘ringleaders’ with eighteen; presumably Cook identified the ringleaders in the time-honoured military way: every fifth man.48 Cook had originally intended a longer stay in Van Diemen's Land, but this gross breach of discipline upset him and he decided to leave at once. Contrary winds delayed him, so he set the men to fish. Soon there was contact with the aborigines. Nine of the locals, Melanesian in racial type, approached but impressed all the Europeans as being very stupid. Their matter-of-factness about nakedness and physical functions appalled even the veterans of Polynesia. Anderson the surgeon reported that men would play with their penis as if with a bauble and would squat to defecate without any shame or sense of privacy: ‘the men never changed their posture on making water and would sometimes not even move their legs out of the way but would suffer the urine to run down upon them’.49 James Burney confirmed this and he compared their insouciance to the way a dog lifts up its leg to urinate: ‘one of these gentlemen will pour forth his streams without any preparatory action or guidance, or even appear sensible of what he is doing; and not in the least interested in whether it trickles down his thighs or sprinkles the person next to him’.50 The first contact with the aborigines came to an abrupt end when the show-off Omai, always keen to impress his superior savoir faire on primitives, fired a gun which made them scatter in panic. Cook was so disillusioned by the impressions he had formed of the locals that he decided he would not after all leave behind the cattle, sheep and goats with which he hoped to turn Van Diemen's Land into a pastoral paradise. He did, however, leave behind a boar and a sow hoping that they would not be killed and eaten and would produce a litter of piglets.51

On 29 January the winds still made it impossible to leave, and there was further contact with the aborigines. The seamen took liberties with the indigenous women, examining their genitals with lustful intent, but as soon as it was apparent that they had sexual congress on their minds an aborigine elder gave a signal and the women melted away. This prompted Cook to ponder further the issue of his sailors' sexuality. He realised he could not stop them having intercourse with native women, but was resentful at the way the seamen habitually offered gifts and trinkets in exchange for their sexual favours. It seemed to him that the only possible consequence of such dalliance was to alienate the local men and make his job more difficult. The unsuccessful overtures the seamen had made to the aborigine women prompted another reflection: it was a golden rule in primitive society that if the women were ‘easy’ the local men would offer them for prostitution; if this did not happen, it was a waste of time for the sailors to try to barter for them.52 At last the winds changed and it was possible to leave; Cook was anxious to get away and did not bother to circumnavigate Van Diemen's Land as he took it for granted it was joined to the mainland. Yet having been delayed by windless days, he was no sooner out to sea than he was hit by a violent tempest – the kind that is sometimes called a ‘perfect storm’ as two different storm fronts collide to produce a hurricane.53 When this died away at the end of the first week of February, there was a further calamity when Clerke signalled from the Discovery that one of his marines had fallen overboard in the night; the man was not seen again.54 The only notable event in the crossing of the Tasman Sea thereafter was the fog, and the conjunction of seeing killer whales (orcas) on the same day as a ‘huge shark’, in these waters probably a great white (Carcharodon carcharias). Three days later, on 10 February, the voyagers sighted the coast of New Zealand; Cook steered for Cape Farewell and on the 12th anchored in Charlotte Sound, his old New Zealand ‘base’. This was his fifth time in New Zealand – the first had been the circumnavigation in the Endeavour in 1769, and the second, third and fourth stopovers were preludes to exploring the great Southern Ocean on his second voyage. For romantics this part of the world was always a revelation. Banks had written of the sensuous thrill of the melodious wild music of the Maoris counterpointing the exquisite beauty of the locale, and this time it was Thomas Edgar, the Discovery's master who responded in the same way.55

Yet for the crew New Zealand and Charlotte Sound had a strong resonance and a very different and definite meaning: this was where their shipmates on the Adventure had been slaughtered. They expected Cook to extract revenge, but his very first reaction was to assure the Maoris who came out in canoes to inspect them that he came in friendship and did not harbour vengeful thoughts.56 If this ‘liberal’ attitude alienated Cook's men, it stupefied the Maoris. They fully expected that they would have to pay for the killing and eating of the white men three years earlier, for this was an attack on a chief's mana: if he did not respond, he was nothing, a man of zero credibility. Not for the first or last time in human affairs, a ‘softly softly’ approach was read as weakness; restraint, meant to teach the locals the meaning of civilisation, bred merely contempt. Cook's peaceable approach seemed wilful perversity, both to his seamen and to the Maoris. Some of the latter recognised Omai and knew he had been in the Adventure party, which seemed to make retribution a certainty, yet nothing happened. Later a chieftain named Kahura, who had led the party that massacred Furneaux's men, put in an appearance, but Cook did not even try to apprehend him.57 It was clear to the seamen that Cook favoured ‘savages’ over them; since the visitors referred to all indigenous people as ‘Indians’, Cook was what in nineteenth-century American frontier parlance would be called an ‘Injun-lover’. In retaliation, at least some of the sailors refused to sleep with the local women who were offered so profusely by the Maori men. In most cases, though, human nature won out and, though with gritted teeth, the seamen still took their pleasure. Cook, who should have been addressing the men's concern about revenge, continued to fuss and fret about intercourse with local women. He admitted he could do nothing about it but dreaded its consequences in all forms, consoling himself with the consensus opinion that ‘natives’ never attacked while their women were consorting with sailors.58 Prostitution was not the only form of useful symbiosis, for when Cook set up tents on the shore to enable Bayly and King to start making astronomical observations, the Maoris camped alongside them and generally fetched and carried. Cook spent most of his time either directing grass-cutting parties so that the cattle could be fed or visiting the Maoris pas, marvelling at their canoes, and pondering their warlike nature.59

The Maoris were astonished at the Noah's Ark Cook disembarked. Although at first Cook posted strong guards to protect the shore parties, once the Maoris bedded down beside his men he gradually relaxed and took the menagerie ashore, partly to distribute horses, cattle, sheep and goats among the locals as part of the ‘improving’ scheme, and partly to stretch the legs and feathers of those continuing on to the Society Islands. The Maoris appeared not to have seen either horses or horned cattle before.60 Gradually, too – one is tempted to say inevitably – relations between the locals and the visitors worsened. Some of the sailors took the line that, after the Adventure massacre, the Maoris ‘owed’ them, especially since Cook obviously intended to do nothing about the situation. Meanwhile the Maoris had grown contemptuous of a man who would not reassert his mana by taking revenge on the Maoris. They would have had more respect for Cook if he had killed some of them, the strangers seemed of no account, and their confidence grew. Soon they were using the sailors' ploy against them, accepting gifts and refusing to give anything in return.61 One warrior even boasted openly that he had eaten an Adventure man. For Omai, the peaceful reception of Kahura was the last straw. When he first saw him, Omai threatened Kahura with death, but Kahura treated this as an empty threat and, to rub in the humiliation, returned next day with his extended family of twenty souls, virtually laughing in Omai's face. Omai completely lost his temper and in a high rage shouted at Cook: ‘There is Kahura. Kill him!’ While Kahura went on deck to have his portrait painted by Webber, Omai bearded Cook in the Great Cabin and raged at him. ‘Why do you not kill him? You tell me if a man kills another in England he is hanged for it and yet you will not kill him, even though a great many of his own people would like that and it would be very good.’62 The general derision felt for Cook by his crew found expression on the Discovery, where James Burney connived at and encouraged an express act of defiance and contempt for his commander. Edward Riou had acquired a pariah dog from the Maoris, which was deeply unpopular as it liked to bite people. The midshipmen and master's mates staged a mock trial of this dog for cannibalism, convicted it, killed it, then cooked and ate it.63

Faced with the dual threat of insubordination from the Maoris and disaffection from his own men, Cook left New Zealand at the earliest possible moment. He cleared from Queen Charlotte Sound on 25 February, taking with him two Maori youths. At the very last moment Te Weherua and Koa, little more than boys, were loaded on, in response to Te Weherua's caprice (and possibly Omai's bad influence), which Cook ought not to have indulged. Once Cook had reached the point of no return on the open ocean, the Maori youths seemed to regret their foolish decision; they wept piteously and continued to do so for days. Eventually, though, they cheered up and became great favourites with the sailors.64 Cook was behind the impossible schedule drawn up in London which originally envisaged his leaving at the end of April 1776, ready to be on the north-west coast of America by June 1777, but authorities are divided on how much the timetable really mattered to him; he had, after all, been instructed that in the end all was to be at his discretion. At any rate, if speed was his primary concern he should now have headed directly northeast across the Pacific to Tahiti. But Cook estimated that at this time of the year the favourable westerlies would not be with him and therefore that he would have to make northing in a more zigzag manner. For the whole of March he encountered calms and irritating south-easterly breezes, further slowing his progress. Cook complained bitterly in his journal,65 but things could have been a lot worse; in these latitudes this is the season for cyclones and hurricanes. Whether it was sheer boredom or pent-up resentment about their commander's poor showing in New Zealand, the crew were in mutinous mood. An epidemic of minor thefts ended with a theft of meat from the mess of the Resolution. When the men would not surrender the culprits, Cook cut the meat allowance to two-thirds; the seamen responded by refusing to touch even the proferred two-thirds, which Cook considered ‘a very mutinous proceeding’.66 Cook was already being caught between the two fires that would bedevil the entire voyage. On the one hand, he was faced by sailors far more strident, assertive and disaffected than any he had known previously; on the other, forced by circumstances to concede that his ‘tolerant’ treatment of indigenous people had not worked, he was gradually becoming a hardliner.67 Whether old age had made him increasingly irritable and short-tempered; whether he regarded the native peoples as ingrates after all he had done for them (at least in his mind); whether he had turned violently against the whole idea of the ‘noble savage’ and the Rousseauesque view of man as intrinsically good and perfectible, and now regarded humans as sinful and incorrigible; or whether, indeed, he had become the victim of delusions of grandeur and thus regarded any opposition, whether from aboriginals or sailors, as a kind of lèse-majesté; all this must perforce remain at the level of speculation, though it seems there is merit in each of these views.68

After a tedious month, on 29 March, Mangaia (one of the Cook islands) was sighted. The reef and pounding surf, as much as the unfriendly locals who came out to meet and challenge them in war canoes, were not inviting, so Cook looked for a more enticing land farther north and found it at Atiu on the 31st, though contrary winds prevented anchorage until 2 April. Again Cook faced high surf, a reef and steep coral rocks. Gore made a tentative sortie in a boat and came back to advise Cook that the best course might be to try to persuade the locals to bring the trade goods the ships needed out to the boats, lying beyond the booming surf. Cook thought this worth a try, so on the 3rd he set out with three boats and Omai as interpreter.69 Cook was worried that if Gore and his party were attacked, the reef would place an impossible barrier between the ships and the three boats and awaited the outcome nervously. On this occasion Omai finally proved his worth, for his swaggering boastfulness managed to strike just the right note with the islanders. The initial overtures produced a barrage of questions: were the strangers arioi, did they come from the Society Islands, were they perhaps envoys of the god Oro?70 Omai was at first nervous, for to begin with the locals were far from friendly and gave their guests nothing to eat until the evening; when an oven was lit to cook a pig, Omai feared that he himself might be on the menu. Yet gradually he impressed the islanders with the might and power of the newcomers. He told them of the capability of European guns, at which the Atiuans were openly sceptical. Omai then gave a demonstration of firepower by exploding the gunpowder from the cartridges he had brought with him. The crackerjack, pyrotechnical effect of the explosion impressed the locals suitably, especially when Omai added that if the white men were not allowed to come and go at will, they would destroy the whole island.71 In the resultant calm and friendly atmosphere Omai made the acquaintance of three Society Islanders who had been shipwrecked on Atiu twelve years earlier after being caught in their outrigger in a ferocious storm. Theirs was originally a large fishing party, and they had drifted for weeks in the Pacific before making landfall, by which time only four of them were still alive (one man had subsequently died).72 A joyful embrace of fellow countrymen set the seal on Omai's most successful day's work yet.

Cook did not get much of what he wanted from Atiu, so the following morning he steered for an uninhabited islet ten miles to the north named Takutea. Here he obtained a quantity of coconuts, scurvy grass and pandanus, which the cattle ate with relish.73 Next he made for Manuae, which from the previous voyage he also thought uninhabited, but it turned out to be occupied, with the result that canoes came out to meet his ships when they plied there on 6 April. Cook needed a good water supply, but the evident hostility of the new inhabitants made that problematical. These people were aggressive, violent and shameless thieves who tried to steal everything not nailed down, including the oars from the Discovery's cutter and even Bayly's servant. Cook used sufficient force to restrain them, but not enough to impress the two young Maoris who, like their elder kinsmen, concluded that Cook lacked mana; such were the rewards of restraint in Polynesia.74 Cook had enough food and fodder to last until the Society Islands but he was seriously short of water. He had taken on 270 tons in New Zealand, but the prodigious thirst of the cattle was the main reason why this was soon reduced to an alarmingly meagre 70 tons. Not wanting to take water by force, he elected to stand away to the Tongan archipelago, where the people had been welcoming on the second voyage. The urgency of his position was indicated by the typically Cook throwaway line in his journal: ‘As it was necessary to run in the night as well as in the day, I ordered Captain Clerke to keep about a league ahead of the Resolution, as his ship could better claw off a lee shore than mine.’75 Cook was now essentially sailing west, away from Tahiti, thus further impairing the precious schedule. The irony was that within the Cook islands he could have found what he needed at either of the rich and fertile islands of Rarotonga and Aitutaki, neither of which, unfortunately, were shown on his charts. With the crew now severely rationed on water (two quarts a day per man), and the water-distilling apparatus proving disappointing, the seamen had to spread the awnings to attempt to catch rain; on 10 April this method proved very effective in a short thunderstorm. The weather seemed to be playing tricks on Cook just when he needed a fine spell, ‘with a wind in our teeth whichever way we directed our course’.76 Yet at last, when both captain and crew were almost in despair, up loomed Palmerston Island.

Here was fresh water and, what was more, plentiful food for man and beast. While the cattle chewed their way through abundant scurvy grass and the green of coconut trees, Cook's foragers gathered nuts, pandanus and palm cabbage for the stock, and fish and seabirds for themselves. Both of these abounded to the point where observers concluded Palmerston must be one of Nature's secret larders. Here for three days the voyagers hunted and fished until the two ships were once again stuffed with edible protein.77 Refreshed in body and mind, the explorers set out for Nomuka but found the going difficult, encountering thunderstorms, adverse winds, high seas and frequent squalls all the way. It was the night of 24–25 April before they limped past Niue, now called Savage Island after the sad experiences of 1774. Next day the fine weather returned and they could see the glimmer of dolphins swimming alongside them in the dark. On 30 April the two ships reached Nomuka, with Cook approaching a little to the south of his track in June 1774.78 He and his companions were recognised and the old pattern of trade started up again, with pigs, breadfruit and yams being bartered for hatchets and nails. Cook gave strict orders that no buying of curios was allowed until all food and water stocks on the two ships were wholly replenished, yet in three days he was able to end all rationing and restore everyone to a diet of pork, fruit and roots. Cook stayed a fortnight on Nomuka. The ships worked round to the old anchorage on the northern shore by 2 May. Here the Discovery lost its best bower anchor on the sharp rocks and began drifting; on 7 May the small bower anchor got hooked up in the Resolution's cable. It was the evening of the 8th before this small bower was unhooked and all the anchors recovered and secured. Even as the work went on, a Nomukan was caught trying to steal a piece of the Resolution's tackle – specifically, the bolt from the spunyarn winch; he was given a dozen lashes and not released until the ransom of a hog was paid over.79

That particular thief was a minor chief, so the flogging had some effect. The problem was that with the lower orders in Nomuka a flogging made as little impression as it would on a drunken sailor. In exasperation Cook actually sentenced one petty larcenist to sixty lashes – enough to kill a man in the Royal Navy. Yet nothing seemed to work as a deterrent. When Cook appealed for help with the epidemic of thieving to the local chiefs, they replied blandly that Cook should simply kill the thieves; Cook declined, on the somewhat Jesuitical ground that he would not use as a punishment – even the supreme penalty – anything that the locals themselves did not view as punishment. Clerke, vexed with the same problem on the Discovery, hit on the idea of shaving the thieves' heads, since a shaven pate was regarded as a great disgrace in local culture. Taking a leaf out of Clerke's book, Cook experimented with the kind of retribution that might be regarded by the locals as a fate worse than death. First he decide to throw all thieves into the sea, and then use them for target practice or get his men to row alongside them and clobber them with oars or transfix them with boathooks. From this he escalated to cutting off their ears.80 Despite all this, Cook and his men mainly enjoyed extraordinarily good relations with the Nomukans. Their chief Tupoulangi gave up his house so that Cook and Omai could stay in it, the chiefs threw coconuts and stones at their own people if they appeared too demanding or rambunctious towards their guests, the common people hewed wood and drew water for their visitors.81 The trade in sex was as brisk as ever, with hachets, shirts, nails and red feathers securing the most desirable of the island houris. To his horror Cook found that venereal disease was already rampant, presumably having been introduced on the 1774 visit; in a new version of la ronde de l'amour the women of Nomuka transmitted syphilis to comrades of the men who had originally given it to them. But Cook apart, no one seemed especially concerned by the threat from sexually transmitted diseases. Samwell, no mean womaniser himself, who kept a record of his conquests on the islands, thought that Nomuka was paradise on earth, a veritable Elysium.82

On 6 May a chief named Finau arrived from Tongatapu. A handsome man of about 35, Finau was presented to Cook by Omai as ‘king’ of the Tongan islands. Perhaps Omai was trying to put his status in terms that the Europeans would understand or, more likely, he was unaware of all the elite nuances on Tonga and simply wished to have it understood that Finau was a person of importance. Anthropologists have unravelled the tangled skein on the islands and explained that power was really exercised through a troika, containing a sacred chief allegedly descended from the gods (the Tu'i Tonga), his chancellor or prime minister (Tu'i Ha'atakalua) and the wielder of real day-to-day power (the Tu'i Kanokupolo), a kind of committee chairman or chief executive. Cook, who saw things through the Georgian lens of ‘kings’, at first overrated Finau, thinking him to be the monarch of the isles, then later underrated him because he realised he did not have supreme status. So-called ‘kingship’ did not work on Tonga, where hierarchies ran horizontally as well as vertically, and where in some contexts a chief could be outranked by someone nominally lower on the pyramid. Actually the deep structure of elite authority was even more complex, as all three Tu'is were outranked by their father's sisters, since sacred status (as opposed to real political power) passed through the female line in Tonga.83 Finau's arrival certainly made an impression. Tupoulangi deferred to him and bowed his head. When Finau came on board the Resolution he laid about him with a stick and drew blood from those of his people foolish enough not to heed his every command. When an officer protested at his brutality, Finau laughed and said that the Tongans expected such a reaction from a Tu'i, for otherwise he would be deemed not to have mana.84 Thereafter Finau dined with Cook every day in the Great Cabin. He was shrewd enough to see that the food supply on Nomuka was becoming exhausted after a fortnight of providing for 200 white men. He did not want the same inroads made on his own island of Vava'u, and suggested that Cook and his ships relocate to Lifuka where he could entertain them properly. Cook therefore weighed anchor on 14 May and threaded a northerly course through reefs and islets, past the volcanic islands of Tofua and Kao, following the guideline of beacons which Finau ordered fired to light their passage. The passage on the lee side of the islands was studded with dangerous reefs, but it was better than being on the explosive windward side where the open Pacific roared in. The voyagers came to anchor on the northern shore of Lifuka on 17 May.85

The visitors were greeted by the usual throng and brisk trade began: pigs, fowl, fruit and vegetables for hatchets, knives, cloth and nails. Finau addressed the island elders and then the common people, ordering them not to steal from the Europeans. After Cook had handed over suitable gifts to the island chief and dined him and Finau aboard the Resolution, Finau announced a ceremony of welcome for the next day. The following morning a crowd estimated by Cook at 3,000 strong gathered to watch a procession of 100 warriors who stacked masses of yams, plantains, breadfruit, coconuts and sugar cane in two neat piles, topping them off with six hogs and two turtles. Finau explained that one pile was Cook's, the other Omai's.86 Despite Cook's strictures on Omai's intelligence, the latter had succeeded in making himself the indispensable go-between and now appeared to be Finau's favourite retainer. Another procession then appeared with more fruit and vegetables, and two more hogs and some chickens laid on top. A sensitive soul might have read this as meaning that the islanders had now brought all the food they had, so that the visitors should take it gratefully and depart. Cook, though, never seemed to appreciate the razor-thin margin of subsistence on which Polynesian society operated. He remarked that the food supply ‘far exceeded any present I had ever before received from an Indian prince’87 but seemed to make the unwarranted inference that the Tongans were therefore as rich as maharajahs and nizams. He and his men stayed on to watch boxing and wrestling matches and were appalled to find that some of these bouts were between women. Next morning Cook's officers strolled nonchalantly all over the island. Under the surface the tensions were simmering. It seemed that, even after all the food and produce given them, the strangers would not be departing soon. Then came the real trigger for the subterranean resentments. Tapa, Tupoulangi's deputy, had come to Lifuka with Finau, bringing his son. Now the son took a fancy to one of the Discovery's cats. Caught trying to smuggle the animal off the ship, the boy was clapped in irons. Clerke was especially troubled with an infestation of rats and he needed every last one of his felines to combat them. As he remarked with his trademark irony, the Tongans had managed to take ‘all my cats, which were very good ones, and as they did not take the rats with them, of which the ship was full, I felt this proof of their dexterity very severely’.88 The Tongans were angry that the son of a chief should be punished for such a ‘trivial’ matter, but Clerke stood firm and let it be known that Tapa's son would not be released until all the stolen cats were returned.

The cat incident and the disinclination of the Europeans to leave convinced the local chiefs that violence against the intruders was the only answer. A conspiracy was hatched; Finau was not the originator but he advised and orchestrated it and without his approval it could not have gone ahead. There would be a great night-time dancing exhibition, illuminated by flambeaux; Cook and his men would be invited and then massacred.89 Finau pointed out that the coup would be complete only if they could also capture the two ships and that would be very difficult at night; he proposed the killing take place by day, and there would be nothing suspicious about this as Cook had already agreed to attend a day-long exhibition of dances. Finau knew how European firearms worked and he even had a plan to reduce the expected Tongan death toll. He asked Cook if, in return for all the lavish entertainments prepared for him, he would ask his marines to drill in public and fire off their muskets in unison after the first set of dances. Cook, suspecting nothing, agreed.90 The discharge of the muskets was to be the signal for the Tongans to rise up and kill the ‘wizards’. Reinforcements would doubtless arrive and could then be picked off piecemeal until the Europeans were so weak that they would be unable to repel a concerted attack on their ships. If all went well, 200 white bodies would soon be lying bleaching on Lifuka beach. Cook and his men arrived, an exquisite and beguiling ‘harlequin dance’ was performed, the marines carried out their exercises (albeit in a ramshackle way) and fired off their muskets. Then nothing. What had happened? It seemed that just before the entertainment began the local chiefs had second thoughts and decided to revert to the idea of a night-time attack. When Finau was told this, he flew into a rage at the insolence of these minor chieftains daring to oppose their views to his. He cancelled the entire operation forthwith and stormed off in fury.91 Any thought the locals might have had of defying Finau and going it alone were dispelled by the performance Cook laid on that night. A display of fireworks and skyrockets accompanied with loud aerial bangs and explosions awed and stunned the Tongans. King reported the psychological ascendancy gained thus:

Such roaring, jumping and shouting … made us perfectly satisfied that we had gained a complete victory in their own minds. Sky and water rockets were what affected them most; the water rocket exercised their inquisitive faculties, for they could not conceive how fire should burn under water. Omai, who was always very ready to magnify our country, told them they might now see how easy it was for us to destroy not only the earth but the water and the sky; and some of our sailors were seriously persuading their hearers that by means of the sky rocket we had made stars.92

The torchlit festivities continued with an unparalleled display of erotic dancing from the Tongans, which in their lubricious intensity aroused lustful thoughts in even the most straitlaced, prudish and puritanical European observers. John Webber sketched furiously, and the evening came to an end with quasi-orgiastic couplings between the sailors and the local beauties, who could be bought for a shirt or an axe.93 The conspiracy had failed, but the underlying tensions did not go away. Cook continued to be almost breathtakingly naïve in his acceptance at face value of Finau's continued protestations of friendship; doubtless it massaged his ego to think that he was singularly adept at handling ‘the natives’.94 Yet thefts continued apace; Cook complained to Finau but nothing was done. Cook therefore decided on a draconian policy towards all offenders, both the Tongans and his own men. He doled out fifteen lashes to a thieving Tongan while punishing one mariner with twelve strokes for losing a boathook and meting out the same penalty to another for the loss of a ramrod.95 By now even the rather obtuse Cook was getting the message that he was no longer welcome. Finau asked him to stay on for a few days while he went to his island to fetch some red feathers. Finau's motivation for this is obscure: he might have been planning another coup or he might simply have wished to absent himself from any phoney leave-taking ceremony. Certainly when Cook offered to accompany him to Vava'u, Finau replied with the whopping lie that there was no suitable anchorage there (the harbour at Vava'u was excellent). A more telling pointer to Tongan feelings was the false report spread by the Lifukans that a European ship had made landfall in one of the southern islands; even Cook could see that this was a transparent ruse to get him to move on.96 Cook accordingly made his way down the coast of Lifuka to its southern neighbour Uoleva, intending to make an inner passage among the islands to Tongatapu. He sent Bligh ahead to reconnoitre, who came back with news that the passage between the islands was studded with shoals, breakers and islets. Cook therefore decided he would have to follow a northward track outside the islands.97

While Cook was anchored in a bay off the southern coast of Lifuka, on 27 May, he received what he recorded as a confusing visit from yet another Tongan ‘king’. This time the visitor came as close to that title as differential traditions would allow, for this was the Tu'i Tonga himself. Paulaho, as he was called, was a hugely fat man of about 40, deliberately obese to reveal his status – if Cook had known enough about Tongan culture he might have guessed that the slim-built Finau could not have been the supreme ruler. Paulaho's role could scarcely be denied, for when Finau returned he too deferred to him – a hard blow for Omai to take, as he had staked his reputation on identifying the power in the land, had become friendly with Finau, and now had to endure this ‘interloper’. Cook found him easier to get on with than Finau, doubtless because the Tu'i Tonga was all pomp and ceremony, and unlike Finau did not have to make nice political calculations.98 When Cook was prevented from setting sail on the 28th by contrary winds, Paulaho ‘compensated’ him with a bonnet of red feathers. He seemed to trust Cook much more than Finau ever did and, when Cook was eventually able to weigh anchor, he left his brother and six of his retinue behind on the Resolution. Fortunately for Cook, he had to spend only one night with these cuckoos in his cabin, for Paulaho and his court followed in their canoes and took them back on board; it turned out they had not been given permission to stay on Cook's ship and Paulaho was angry with them for their disobedience.99 Cook intended to call briefly at Nomuka now he had the protection of the Tu'i Tonga and then proceed to Tongatapu, but the passage south proved difficult and dangerous, in among reefs and breakers and beset by sudden squalls. He passed Lofanga but then, on 31 May, went through yet another of those nerve-shredding experiences in which his career proliferated. Tacking in a bizarre manner, which makes his track on an oceanic chart look like the peregrinations of a drunkard, Cook tried to squeeze between the islets of Kotu and Fotuha'a, but was caught in a severe squall and spent a terrifying night tacking in the dark under reefed topsails and foresail.100 All hands were on deck all night because of the danger; the Resolution had to keep firing her guns to warn the Discovery astern. Cook describes the experience:

I kept the deck till twelve o'clock when I left it to the Master, with such directions as I thought would keep the ships clear of the dangers that lay around us; but after making a trip to the north and standing back again to the south the ship, by a small shift of the wind, fetched farther to windward than expected; by this means she was very near running plump upon a low sandy isle surrounded by breakers. It happened very fortunately that the people had just been turned up to put the ship about and the most of them at their stations, so that the necessary movements were not only executed with judgment but with alertness and this alone saved the ship … Such risks as these are the inevitable companions of the man who goes on discoveries.101

Cook anchored two miles off the uninhabited islet of Kotu and waited three days for the winds to die down. Paulaho came up with him in his flotilla of canoes and he and Cook walked Kotu together.102 On 5 June Cook brought his ships in to Nomuka again for a brief stay. This was the occasion when Finau caught up with Paulaho and evinced his inferior status by being unable to sit at table with the Tu'i Tonga. Paulaho seemed to have no great liking for Finau and told Cook he did not trust him. Perhaps alerted by the supreme ruler to Finau's murderous and mendacious nature, Cook was sceptical when Finau told a long, circumstantial tale, whose upshot was that he was not bringing Cook any provisions since the canoes bearing the goods and their crews had all perished in the recent gales; from looking at Finau's followers' faces Cook could see at once that this was a lie. By now he had come to realise that Finau's main aim was to cut down on the sustenance offered to the visitors in the hopes that they would shortly depart or, at the very least, to keep them away from his beloved Vava'u.103 Disillusionment with Finau was not the only headache. Many of the crew seemed to be suffering from ‘Tonga flu’ – a relatively mild virus that produced sore throats and a hacking cough, and on Nomuka the news was bad: all the seeds he had left on the island had been eaten by ants.104 He stayed no longer on Nomuka this time than he had to. Paulaho went ahead in his canoes to Tongatapu, easily outdistancing the two sloops with his massive rowing power. Finau left behind pilots to guide them to a safe haven, but quite how knowledgeable these ‘experts’ were must remain problematical (unless Finau had issued secret instructions for sabotage), for as they threaded through the Lahi passage to Tongatapu they nearly ran aground on a coral shoal; both ships grazed the coral slightly but the water was deep so they slid through and came to anchor without damage on 10 June.105

Tongatapu, the seat of the Tu'i Tonga, was the largest and richest of all the Tongan islands. The fertility of the island amazed the visitors, as did the warmth of their reception. There were old friends to meet such as Ataongo, Cook's pal from his previous visit and Tupu, Furneaux's ‘brother’. There was also the traditional kava-drinking ceremony that Paulaho laid on for them. To the astonishment of the locals Cook unloaded his entire menagerie: pigs, cattle, horses, goats, sheep, turkeys, geese and peacocks.106 Paulaho next told Cook that the two of them should pay a visit to Tonga's Number Two potentate, the Tu'i Ha'atakalaua, or supreme secular authority, an elderly man named Maealiuaki who in his younger years had done the job Finau was now doing.107 However, to conform with protocol the Europeans had to strip to the waist, and at this suggestion Cook protested vociferously, pointing out that one did not have to do that even when having an audience with the mighty King George of England. In the end Paulaho said that their naval uniforms would show enough respect for the old man's mana. But when they made the trip inland to see Maealiuaki on 12 June, they were told that the old man was ill or unavailable. Cook construed this as a brush-off and stormed off. Whether Maealiuaki had himself been in dudgeon because the strangers would not abase themselves in the prescribed manner and was then talked round by Paulaho, or whether the captain's intemperate behaviour had unbalanced and unsettled the Tu'i Tonga, the upshot was that the previously unapproachable old man next day went himself to Cook's ships for a meeting.108 This was a great success: Maealiuaki toured the shore camp, inspected the cattle, examined the observatory and, with Paulaho, dined in the Great Cabin. Paulaho developed such a taste for European wine that he made a point of dining aboard the Resolution every day she was at the island. Cook and Clerke visited him in his royal residence, while Cook and Omai also made reciprocal visits with Tupu. Cook still relied on Omai for translation but was again starting to lose patience with him. He could never quite make out whether the Society Islander was more or less intelligent than he seemed, and whether Omai misunderstood or mistranslated the Tongans' words or simply kept things from him.109

For the first two weeks of the unconscionable one-month stay on Tongatapu Cook maintained good relations with the rulers of Tonga, but this entente was gradually whittled away as Cook began to react more and more harshly to the epidemic of thefts. At some stage during the voyage from New Zealand to Tonga Cook reflected on the ungrateful reaction of the Maoris to his clemency and non-retaliation for Grass Cove, and concluded that he had been gravely mistaken; it was clear that Polynesians reacted only to force and construed restraint as weakness.110 By the time he reached Tongatapu he had decided that theft warranted the strongest possible retaliation on the offender, short of death. He ordered his sentries not to open fire, or at least not with lethal ammunition, for fear this would spark a general conflagration but instead ordained beating, slashing, ear-cropping, head-shaving and other draconian punishments. As Beaglehole put it: ‘He flogged, in ascending dozens, he put in irons, he cropped ears, he slashed with a knife the arms of men he regarded as desperate offenders.’111 This was certainly, at the pragmatic level, the correct course of action, although it affronted liberal officers such as King. Tongans had scant respect for people who allowed themselves to be put upon with impunity, and the punishments, severe as they were, were a bagatelle alongside some of the local customs, such as human sacrifice.112 The significance of Cook's change of mind was what it reveals about his changing personality; gone is the ‘softly, softly’ approach, the benevolent paternalism of the son of the Enlightenment, and in its place is a hawkish, unforgiving hard-liner animated by Old Testament principles of revenge and smiting. Cook had always been short-tempered, but on the third voyage he increasingly exploded in volcanic rages. The midshipman James Trevenen reported that the men used to call Cook's tantrums heivas: ‘the name of the dances of the Southern Islanders, which bore so great a resemblance to the violent motions and stampings on the deck of Captain Cook in the paroxysms of passion’.113 James King concurred. According to Edmund Burke, he ‘never spoke of him but with respect and regret. But he lamented the roughness of his manners and the violence of his temper.’114

Sympathetic observers might say that Cook had plenty to fume and rage about. The Tongans were expert thieves and would steal anything not nailed down and much that was. As Beaglehole wryly remarks: ‘They stole from a sentinel set on shore to prevent stealing.’115 The early thefts – of a pewter basin and a sentry's ramrod – were perhaps no more than irritating, but the thievery soon escalated to a more serious level. An attempt was made on one of the Discovery's anchors – foiled only because it got hooked in a chain-plate and could not be worked free by hand.116 When a goat was stolen, Cook decided the best way to prevent further purloining of stock was to distribute at once the animals he intended as a parting gift. On 19 June he began distributing the cattle. He delivered a careful lecture on animal husbandry and told the audience that there was no further need for theft because he was giving his prized livestock away free. He then proceeded to apportion the cows according to the rank of the recipients but inevitably, he missed some of the social nuances and left certain individuals aggrieved. Next day he found that a goat and two of the turkeycocks he intended to take on to Tahiti were missing. Incandescent with rage at such ‘ingratitude’, he seized the three high chiefs of Tonga plus three canoes and their crew and announced that they would be held until the missing animals were returned. The sacrilege in seeing their Tu'i Tonga made prisoner concentrated minds, and the stolen beasts were returned.117 Cook released the chiefs and Paulaho tried to pour oil on troubled waters by holding a magnificent feast next day, with another extravagant display of dancing. Nonetheless the incident seriously soured relations and caused the chiefs to be wary. When some muskets were stolen on 23 June (perhaps ironically from the two most unpopular officers on the voyage, Bligh and Williamson), the three chiefs, knowing Cook's likely reaction, fled to the hills.118 From there Paulaho sent an offer of reconciliation to Cook, who was concerned that his men were now coming under sustained attack from stone-throwers and his officers being assaulted while in the countryside. Poulaho offered to provide an escort for any of the scientists or officers proceeding inland. Although Cook accepted this as a gesture of good faith, it did not suit all the Europeans to have Tongans as escorts. Samwell, for instance, spent most of his time on clandestine amatory trysts and needed to be alone. On one of these jaunts he was physically assaulted and responded by opening fire, in defiance of Cook's standing orders. On 28 June a wood-cutting party came under severe and prolonged attack from the islanders, who rained down coconuts on them.119

Cook became more hard-line and ferocious, even during the sojourn in Tonga. When he had imprisoned Tapa's son on Lifuka for stealing a cat, the egregious Omai suggested to Cook that he give the culprit one hundred lashes. Cook gave him just one, which even so was taken by the Tongans as a gross insult. By the time he was on Tongatapu, something had snapped and he was prepared to order lashings well above the legal maximum of twelve laid down by Navy regulations.120 He had by now worked out an effective method of dealing with thievery by chieftains and oligarchs: after they had been flogged, they had to pay an additional penalty in pigs. But he had no deterrent with which to ward off the depredations of the common people, so in desperation turned to the cat-o'-nine-tails. When a dozen lashes did not cut down the incidence of theft, he increased the number to two dozen, then three dozen, then four dozen, eventually going as high as seventy-two lashes. Additionally he cut off men's ears, fired at swimmers in the sea, maimed them with oars and boathooks and ritually cut at least one man on the shoulder.121 Not only was Cook wildly exceeding the powers granted to him as a Royal Navy captain, he was also alienating the Tongans and shooting himself in the foot, since such extreme penalties bespoke extreme impotence. Even Cook's officers thought his actions constituted ‘cruel and unusual punishment’ and were self-defeating as well. Where the Tongans at the beginning of the month-long stay in Tongatapu used to be welcoming and hospitable, now they shut the doors of their houses against the visitors, reacted to them sullenly, stopped trading and went out of their way to rob or insult any Europeans they encountered on shore.122 Passions were rising on both sides. Cook discovered that one of his sentries had seriously wounded a Tongan with a musket ball and set up a board of inquiry to try to discover how his express orders that his men fire only small shot had been flouted. The proceedings ended in farce, because the entire corps of marines closed ranks and swore on a stack of bibles that the Tongan had simply been grazed with small shot.123

This came close to mutiny and Cook, sensitive and even paranoid about such manifestations in his crew, struck back hard, ordering multiple lashings for recalcitrant seamen. Undoubtedly, too, he was displacing on to them some of the murderous rage he felt towards the Tongans and which he dared not indulge in openly lest it trigger a bloodbath. He flogged eight of his own men for various offences on Tongatapu, five of them with a dozen lashes each.124 Alongside Cook's hardening attitude to the Polynesians on the third voyage one can clearly perceive a more brutal response to his men; on the voyage of the Resolution and Discovery he punished twice as many men (with 736 lashes in total) than he had on the two previous voyages combined.125 Given that Cook was (literally) lashing out at both seamen and Polynesians in 1777, Omai may be considered lucky to have escaped his wrath. His offences were twofold. In the first place he came to blows with a corporal of marines and, when he appealed to Cook, did not get the satisfaction he required; Cook, indeed, took the line that the affray was Omai's own fault. Then he angered Cook by setting himself up as the official intermediary between the ship's officers, who were complaining about theft, and Paulaho, thus cutting out Cook altogether.126 Yet Cook took a complaisant attitude to Omai's casual dalliance with a local girl, and in this regard Omai was not the only one to escape the magma of Cook's volcanic wrath on Tongatapu. He drew the line at interfering with his men's sex lives, which were as strenuous here as on all other Pacific islands. Samwell was well to the fore in this regard, but he was far from the only one – hardly surprisingly since the Tongan houris were rated by some of the men as the most lascivious in all the islands.127 Even the two young Maoris Te Weherua and Koa got into the lubricious action (through Omai's bad influence, Cook thought), as a result of which Te Weherua contracted a sexually transmitted disease (probably yaws). It was the old story. The locals spread yaws among the sailors and they retaliated by infecting their hosts with gonorrhoea and syphilis.128

In the (rare) intervals between flogging his own men and the Tongans and making angry moves againsts the chiefs, Cook (contradictorily) spent most of his time at formal ceremonies with Paulaho, trying to conciliate him. It is surprising that the Tongans, having earlier planned to massacre Cook and the Europeans, did not react with more force to Cook's provocative floggings and maimings, but the answer may be that Paulaho was using Cook in his own power struggle with Finau, who scarcely appears in the accounts of the month-long stay at Tongatapu. Cook's own journals are full of lengthy and somewhat tedious accounts of six-hour-long dances and other rituals, each one seemingly conducted under a different rubric. First, on 17 June, there was a ceremony to ask the gods for a successful yam planting season. This consisted of a theatrical show mimicking yam-planting, the ‘presentation’ of yams and breadfruit, five hours of daytime dancing and then, in the evening, a long series of night dances.129 Cook felt that his credibility required an answering ceremony next day, in which his marines were again put through their paces and again failed to impress. Against his own usual practice, Cook allowed his men to fight the locals in wrestling matches. When they were all soundly thrashed, he felt he had to regain the face lost by another display of European technological superiority, involving fireworks and water-rockets. Then, a few days later, after the chiefs had fled into the hills and Cook had sent Omai after them, there was a propitiation ceremony, which essentially meant another massive presentation of food by the Tongans to their visitors: hogs, turtles, fish, yams and breadfruit, piled into two food mountains each 30 feet high. Paulaho then presented red feathers and the evening closed with night dances.130 After some further embarrassing incidents, on 25 June, Cook accompanied Paulaho to the ritual centre at Mu'a, visited the sacred burial grounds of the Tu'i Tonga's family and spent the night in his house. All this diplomacy, though cordial enough, and eked out with many a kava-drinking ceremony, failed to settle the simmering tensions on the island and the rampant theft.131 On 1 July Cook announced that he was setting sail, but contrary winds continued to detain him. Paulaho made a formal farewell, the ships moved to a different anchorage ready to sail on the first favourable breeze, and the chapter at Tongatapu seemed closed.132