Everybody killed the Jews.

—ADOLF EICHMANN, TRIAL TESTIMONY IN JERUSALEM, 1961

WHAT TO DO NEXT? That was the question Uris faced after the acclaim, attention, and money generated by Exodus. He was a rich, recognized writer. But what would follow? In part, the question answered itself. Writing the Warsaw Ghetto section of Exodus (Book 1, Chapters 22 and 23) had troubled him, as had the interviews he conducted in Israel with ghetto survivors. He wanted to memorialize their courage in a work that would continue his theme of the fighting Jew. He wanted to show that in even defeat they had triumphed, and in death they had survived. He also wanted to return to Israel to acknowledge his role as its literary spokesperson and, at the same time, to use the trip to fashion another book about the country, this time in photographs. To help him, he enlisted the Greek photographer, Dimitrios Harissiadis.

But first, there were appearances to make. On 19 September 1959, Uris was onstage with Golda Meir and Levi Eshkol at the Sherman Hotel in Chicago.1 His status as a voice of North America Jewry was immense, and the National Economic Conference for Israel was not going to pass up the chance to have him on the dais with the leading Israeli political figures. Uris, a willing supporter, became a frequent speaker at Jewish organizations throughout the continent, and many awards followed.2

Next month he was back at high school, receiving John Bartram High’s Outstanding Alumnus award (26 October 1959). This was ironic, since he had left school before graduating in order to join the marines in January 1942. The report in the Bartram High paper did note that he received a war diploma from the high school, but failed to record that it was more honorary than authentic. Nevertheless, he impressed the students with his oft-repeated quip that, fortunately, “English and writing have absolutely nothing in common.”3

In response to the immense popularity of Exodus, other writers came forward with stories, no doubt trying to gain attention: Yitzhak Perlov, for example, a Yiddish writer from Tel Aviv, claimed that he had published a novel in 1949 in Argentina called Exodus 1947. He was one of the 4,500 passengers on the Exodus that had to return to Germany. His novel is about the journey. Others tried to capitalize on a certain type of notoriety. A passport clerk in the offices of El Al claimed he was being taken for a forger and regarded with contempt because his name was Dov Landau. He requested an injunction against the local distribution of Exodus because he had been mistaken for the book’s character of the same name. His request for the injunction was denied, and he was ordered to pay costs, but he also filed a separate $4,400 libel suit against the publisher and distributor of the book.4

While doing research for Exodus, Uris had visited the Warsaw Ghetto Fighters Kibbutz. A number of survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, known as the “Ghetto Fighters,” went on to found Kibbutz Lohamey ha-Geta’ot (literally: “Ghetto Fighters Kibbutz”), north of Acre. The founding members included Yitzhak Zuckerman, ŻOB (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (Jewish Fighting Organization) deputy commander, and his wife, Ziviah Lubetkin, who also commanded a fighting unit. In 1984, the members of the kibbutz published Dapei Edut (Testimonies of Survival), four volumes of personal testimonies from ninety-six kibbutz members. The settlement also features a museum and archives dedicated to remembering the Holocaust.

Although the Warsaw Ghetto revolt failed, it nonetheless exhibited the courage of Jews in resisting oppression. Uris felt a novel on the subject was justified and would be an extension of his theme of the Jew as hero. Uris then sought to duplicate his arrangement with Dore Schary, although this time with Mirisch Films. In the spring of 1959, he arranged to go to Israel and Poland, a trip made possible by a new deal to sell motion-picture rights to a new book on the ghetto as well as to write the screenplay. The independent movie unit would finance Uris in his research. The deal fell through before he got started, but he and his agents (Ingo Preminger and Malcolm Stuart) penned a new, precedent-setting agreement that had Hollywood talking. A four-picture arrangement with Columbia, it was seen as representing the “rising prestige of the writer in Hollywood.”5 The contract was believed to be the first multiple-book deal in the movie industry (recall that with Battle Cry, Uris had become the first first-time author signed to do his own screenplay). Uris would also produce the movies from the four unwritten novels. Remarkably, Columbia signed without seeing any outlines or manuscripts. The head of the Screen Writers Guild claimed that the contract between the writer and studio was unprecedented.6 Doubleday was to publish the novels.7

Before Warsaw was Israel, where Uris returned to conduct research for his proposed novel, tour the country with his Greek photographer for Exodus Revisited, and participate in the shooting of a documentary starring Edward G. Robinson. Uris left Los Angeles on 8 March 1959 and arrived in Tel Aviv on the 19th after a week in London. He would stay until April 30. He would be in Copenhagen for just more than a week before flying on to Warsaw, where he would spend five days, arriving on 9 May. By the 16th, he would be back in Los Angeles.

Uris’s arrival in Israel was news. The Foreign Ministry invited him to lunch, and various organizations feted him. But his first job was a film: Uris wrote the script for a fund-raising documentary for Israel bonds narrated by Edward G. Robinson. Titled “Israel,” the forty-minute Technicolor film depicted dramatic sites from biblical and contemporary times. Elmer Bernstein composed the music, which was played by the Israeli Philharmonic. Entirely filmed on location, it included footage of Ben-Gurion at home in the Negev desert as well as various social and economic projects.

Exodus Revisited was in some ways a parallel work, a pictorial record of modern Israel. A photo sequel to his novel, the book vividly shows the past and present of the country. Uris even reread Exodus and picked individual sentences to reproduce in the new book in addition to supplying captions and commentaries to Harissiadis’s photos.

The narrative, however, is erratic, veering sharply between terse, factual commentary and effusive prose separated by evocative black-and-white photos. The writing alternates between the simple and the overwritten: “The Jewish people gave to a groping mankind its first great bridge from darkness to light” (EXR, 350) is one example, an echo of a line from Exodus in which Karen tells Kitty the value of Israel (EX, 614–615).

A prophetic tone dominates the book, whether in the story of the revolutionary Simon Bar Kochba, who nearly defeated the Romans, or in the account of the 286 defenders of Masada, who held off Roman legions for three years, only to die when they were betrayed (EXR, 38–39). Throughout the narrative, Uris intersperses facts: Armageddon is at the end of Wadi Ara; Jaffa is the oldest port in the world; eucalyptus trees were imported from Australia “to help drink up the malarial swamps” (EXR, 56). He also summarizes the three aliyahs (immigrations) to Israel and individual heroes in the struggle for Palestine, such as Sarah Aronsohn, who was painfully tortured by Turkish police in her home before she was able to commit suicide (EXR, 58–59).8

Dedicated to David Ben-Gurion, Exodus Revisited offers a truncated history of Israel with short prose transitions made up of one- or two-sentence paragraphs. Christian, Muslim, and Jewish religious landmarks are captured in the black-and-white images of Book One, which has a minimal amount of text. Uris used a different method in his later nonfiction book Jerusalem: Song of Songs (1981; photographs by Jill Uris), which contains a lengthy outline of the political and religious history of Jerusalem.

In many ways, Exodus Revisited acts as a guide, even a set of footnotes, to Uris’s novel. For example, not only does he detail the defenses of such isolated kibbutzim as Dagania, Ein Gev, and Ayelet Ha Shahar—a northern kibbutz that was able to down a Syrian fighter jet with a single rifle shot (every man in the kibbutz modestly took credit for firing the shot), an event that was amalgamated in the story of Gan Dafna—but he gives the sources of some of the most dramatic scenes in the novel. One of the most notable was the night hike with the children from Gan Dafna as the kibbutz faced attack. This had occurred at the mountaintop Kibbutz Manara in the Huleh Valley, where the children were dangerously transported down the mountain between enemy lines to relative safety on the valley floor (EXR, 103). The siege of Safed receives equal treatment, and the book includes a photo of the handmade postage stamps used on smuggled letters (EXR, 108).

Exodus Revisited concludes with a recounting of the adventures of Antek (Yitzhak Zuckerman, a leader of the resistance) in the Warsaw Ghetto, which provided a critical source for Uris in writing Mila 18. The graphic paragraph summarizing the resistance ends with “we hung on for forty-two days…. Not bad when you consider that the entire country of Poland held for only twenty-six” (EXR, 257). Uris spent a week interviewing residents of the Ghetto Fighters Kibbutz and recording details of their struggle, especially the story of Ziviah Lubetkin, a heroine of the ghetto fighting, who survived by crawling through sewers in fetid water.

The book includes several photographs of Ben-Gurion, the most telling being a shot of him conducting a Passover seder inside a tent with paratroopers in the Negev; the image recalls the concluding seder of Exodus and anticipates the late scene in the bunker of Mila 18 of another seder. The final picture is of the sea, captioned by the statement, borrowed from Exodus, that Israel is “a bridge from the world of darkness to the world of light” (EXR, 279).

After his time in Israel and a stop in Denmark, Uris went to Poland, his arrival headlined in the Hollywood Reporter as “Hollywood scripter slides back of Iron Curtain.” According to the paper, Uris became the first Hollywood writer “ever to slide back of the Iron Curtain to research a pic he’ll pilot.”9 In communist Poland, the period of Stalinization had ended in 1953 with Stalin’s death, and the 1956 Poznan worker riots had led to the selection of Wladyslaw Gomulka as the reformist leader of the Polish Communist Party. But Uris still had difficulty obtaining permission to see the remains of the ghetto and Jewish memorials.

His trip was short. The Hotel Bristol in Warsaw served as his base, and Uris would make the hotel the home of the sophisticated Nazi Horst von Epp in the novel. For a week, Uris was subjected to bureaucratic runaround, and received cooperation from the government only after he had shouted at an official for almost half an hour. “Life in Poland is detestable,” he said: “They speak of new freedom [but] the word freedom there doesn’t mean the same thing it does here. They have no real freedom.”10

Uris later described his visit to a human stockyard near Lublin and the failure of the community to prevent the obvious march to slaughter: “Standing on a hill above Lublin I got the full impact of it. The great tragedy was that when the victims would be brought in cattle cars to the Lublin siding to be marched in open view to Maidanek—not a voice in all the city would be raised.”11

Warsaw was something of a return for Uris, reversing the movement of his father, who, in his memoir, wrote often of his travels through the city, especially at the start of his trip to Palestine. Uris had a strange experience there: “I’m a bad sleeper. I have insomnia, but when I got to that Warsaw hotel room, I lay down on that bed and slept for 20 hours like a baby. I had come home. I had come to Warsaw and I was doing something that was obviously pressing very hard to get out. And I had periods like that during this book.”12

The ghetto itself was 1,000 acres, or 100 city blocks. At its height, it held 37 percent of Warsaw’s population on 4 percent of its land. In the Warsaw of 1959, a modern housing complex stood over the destroyed rubble. Nearly three years into the war, after nearly 90 percent of the ghetto’s inmates had been sent to the camps, the resistance took place. The battle began on Passover Eve, 19 April 1943, and ended in May with the fiery destruction of the ghetto.

Before the outbreak of the Second World War, Warsaw was the largest center of Jewish life in Eastern Europe: approximately 375,000 Jews lived there, nearly 30 percent of the total population of the Polish capital. Jewish newspapers, theatre groups, sports clubs, and political parties flourished as the population absorbed émigrés from eastern Poland and parts of the Soviet Union and Lithuania. Isaac Bashevis Singer, who, with his brother, would later flee Warsaw, writes vividly about the culture of Warsaw in The Family Moskat (1950), emphasizing the secular as well as religious aspects of its Jewish culture. Many neighborhoods were entirely Jewish, especially in the northern sectors of the city, with assimilationists living next to the Orthodox.

The invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, however, and the fall of Warsaw on 28 September, brought a quick end to that life. Jews had to wear the Star of David, while property, including radios, was confiscated. Jews were forbidden to change their place of residence and forbidden to use the railways without special permission. They were soon barred from certain professions and excluded from entering restaurants, bars, and public parks. They had to use special carriages on public trams. Following the confiscation of their personal property was the confiscation of monetary assets, all bank accounts being forfeited to the Nazis. Jewish response to these decrees, however, was muted, even if life became unbearable. Those who were on certain “wanted lists,” including Menachem Begin, escaped if they could.

Repression of the Jews increased with the construction of the actual Warsaw Ghetto, beginning in March 1940 when signposts that read “Infected Area” were erected at the entrance of streets densely populated by Jews. That same month, the Judenrat (governing body) received a map of the area, and was told to build a wall around it.13 Adam Czerniakow, a former union leader and chairman of the Judenrat, tried to convince the authorities to cancel the orders. He was ignored, and in late August 1940, work on the ghetto began, turning the existing Jewish quarter into a bordered area. On Yom Kippur, 12 October 1940, loudspeakers in the city notified the Jews that a ghetto was being formed and that free movement in and out of the area would continue only to the end of October. Significantly, the Germans carefully avoided the word “ghetto,” preferring to describe it as the “Jewish Residential Quarter of Warsaw,” a phrase also employed without choice by the Judenrat.14

When the ghetto was sealed on 16 November (unlike medieval Jewish ghettos, which were closed only at night), more than 375,000 people found themselves crowded into an area of one and a half square miles. The German governor of Warsaw, Ludwig Fischer, in a report of September 1941, calculated that roughly 108,000 Jews lived in one square kilometer (0.39 square miles) of the ghetto, in comparison with 38,000 per square kilometer in residential Warsaw.15

The ghetto was irregularly shaped: at one point, the houses and sidewalks of Chlodna Street were included in the ghetto, but not the road, which was considered “Aryan.” The wall around the ghetto was a little more than eight feet high and topped with barbed wire; it had twenty-two gates, reduced in time to thirteen and at the end to only four. German, Polish, and Jewish police guarded the entrances. Approximately 26,000 Jews lived on Pawia Street, and 20,000 on Mila Street. Black marketeering and begging coexisted, and the dead lay exposed everywhere. Photographs from the ghetto show the crowded and destitute conditions; no shot is more haunting than that of a six-year-old boy and his mother, hands raised high and marching before a German soldier who is pointing a gun at him. Uris alludes to this scene in Mila 18 (M18, 509).16

The Nazi explanation for the ghetto was simple. Officially, it was to stop the spread of typhus; unofficially, to contain and then destroy the Jews.17 The Germans’ eradication of the quarter in mid-May 1943 confirmed their original plan. Memories of it survived through journals and fiction, individuals and art, marking its mythic power, which was confirmed by the news in January 2006 that a Jewish history museum will be built where the ghetto used to stand.18

Despite the hardships, life in the Warsaw Ghetto included educational and cultural activities conducted by underground organizations. Hospitals, public soup kitchens, orphanages, refugee centers, recreation facilities, and a school system were formed. Some schools were illegal and operated under the guise of soup kitchens. There were secret libraries, classes for children, and even a symphony orchestra.19

Rampant disease and starvation, as well as random murders, killed more than 100,000 even before the Nazis began mass deportations from the ghetto’s umschlagplatz (collection point) to the Treblinka extermination camp, sixty-two miles to the northeast, during Operation Reinhardt. Between 22 July and 21 September 1942, approximately 265,000 ghetto residents were sent to Treblinka. In 1942, Polish resistance fighter Jan Karski reported to Western governments on conditions in the ghetto and on the extermination camps. They paid no attention. But by the end of 1942, it had become clear that the deportations meant death; many of the remaining Jews decided to fight.20

On 18 January 1943, the first instance of armed resistance occurred, when the Germans started the expulsion of the remaining Jews. The Jewish fighters had some success: the expulsion stopped after four days, and the ŻOB and ŻZW (Żydowski Zwiazek Wojskowy; Jewish Military Union) resistance organizations took control of the ghetto, building shelters and fighting posts, and began to operate against Jewish collaborators. During the next three months, all inhabitants of the ghetto prepared for what they realized would be a final struggle.21

The last battle started on Passover Eve, 19 April 1943, when a large Nazi force entered the ghetto. After initial setbacks, the Germans, under the field command of Jürgen Stroop, systematically burned and blew up the ghetto block by block, rounding up or killing any Jews they could capture. Significant resistance ended on 23 April 1943, and the German operation officially concluded in mid-May, symbolically culminating with the demolition of the Great Synagogue of Warsaw on 16 May 1943. According to the official report, at least 56,000 people were killed on the spot or deported to Nazi concentration and death camps, mostly to Treblinka.

What resources did Uris have to tell his story? Initially, only the accounts of survivors whom he interviewed in Israel, Warsaw, and London. His 1959 visit to the Ghetto Fighters Kibbutz in western Galilee had a tremendous impact; there he heard firsthand the stories of Antek and Ziviah Lubetkin, hero and heroine of the Warsaw uprising. Antek had led the forty-two-day ghetto revolt; Ziviah had commanded the women’s brigade and kept a diary of what happened. His week at the kibbutz imprinted on him the human dimension of the suffering but also courage of the Jews, who fought with little but survived through determination. As Ziviah Lubetkin recalled their escape from the ghetto: “For twelve hours we moved inch by inch in the canals in pitch blackness holding hands in a chain,” waiting for thirty-six hours beneath a manhole cover until help arrived.22 Uris dedicated Mila 18 to the Lubetkins and to Dr. Israel Blumenfeld, a scholar and Warsaw Ghetto fighter.23

The stories and the survivors at the kibbutz moved Uris so profoundly that he later became national chairman of the Ghetto Fighters’ House and Museum, heading a fund-raising drive. He also donated a portion of the manuscript of Exodus for display in the museum. In April 1960, he and Ziviah Lubetkin spoke at Hollywood’s Temple Bethel as part of an observance of the ghetto uprising. This was a heroic time in America. In July 1960, the Democrats nominated John F. Kennedy for president. Uris attended the Los Angeles convention as a delegate and Kennedy supporter.

Besides firsthand accounts, Uris had texts and testimonies retrieved from Yad Vashem (the Holocaust memorial and archive center in Jerusalem), notably Emanuel Ringelblum’s Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto, published in 1958, although Yiddish excerpts had begun appearing in Warsaw between 1948 and 1952. The existence of this archive, one of the most immediate records of ghetto life, is itself remarkable.

Ringelblum was a historian, high school teacher, activist, and social worker. As German repression increased and the ghetto was sealed in November 1940, he realized the importance of keeping an account of what happened, initially to document German oppression and later to record atrocities. He organized a clandestine group of “historians,” who called themselves Oneg Shabbat (Joy of the Shabbat) because they met on Shabbat. Through them, he began to encourage the residents of the ghetto to tell their stories via journals, letters, circulars, diaries, and essays—any form of documentation. The group gave classroom assignments to schoolchildren and later incorporated their reports into the archive. They began to collect records, decrees, drawings, eyewitness accounts, newspapers, even ration cards. Of course, the accumulation of such material was illegal, so Ringelblum recorded events in letters to relatives, which were never sent. Rabbi Huberband, a colleague, wrote his account in the margins of religious books. And everyone contributed—smugglers, students, professors, and policemen—the purpose expressed by nineteen-year-old Dawid Grober, who wrote in August 1942: “What we were unable to cry and shriek out to the world we buried in the ground.”24

As material accumulated and the uprising was about to begin, action was taken to preserve the archive. On three occasions, part of the archive was buried in one of ten metal boxes or three large milk cans. The first cache was buried on 3 August 1942, the second in February 1943, and the third in April 1943. Three of the ten metal boxes were discovered in September 1946, and two of the milk cans in December 1950. The remaining seven boxes and the other milk can have not been located. Nonetheless, more than 25,000 pages of documents have survived, including a 1943 Ghetto poster: “He who fights for life has a chance of being saved: he who rules out resistance from the start is already lost, doomed to a degrading death in the suffocation machine of Treblinka … We, too, are deserving of life! You merely must know how to fight for it!” Oneg Shabbat managed, as well, to smuggle out three reports detailing ghetto conditions to the Polish government in exile in London.25

Uris used the diary form of Ringelblum’s Notes as part of his structure for Mila 18, as had John Hersey for his novel The Wall (1950), which cited a fictitious Levinson archive, supposedly written in Yiddish and discovered in the ghetto. Uris had read Hersey’s novel before he went to Hollywood in 1954 but did not reread it while working on Mila 18. He was critical of it because it put the Jews in a position of slavery, which he abhorred.26 Uris used the diary form to document the increasing violence of the German attack on the ghetto rather than to focus on the fate of individual characters. Preservation of the archive became the crucial goal of the Jewish fighters, while destruction of the archive became the aim of the Nazis who had heard that such a record existed. In the novel, the importance of the escape of the Swiss-employed American journalist, Christopher de Monti, lies not only in the preservation of his life but also in his knowledge of the location of the archive, which, at the end of the novel, he vows to reclaim. His December 1943 entry, which ends the book, also marks the end of the narrative journal.

Ringelblum’s Notes from the Warsaw Ghetto sets the tone and even the theme of Uris’s novel. Late in his account, for example, he describes the morituri (Latin for “those who are about to die”), the bitter pessimism that defines the mood of the beleaguered Jews. However, he then writes: “Most of the populace is set on resistance. It seems to me that people will no longer go to the slaughter like lambs. They want the enemy to pay dearly for their lives. They’ll fling themselves at them with knives, staves, coal, gas … They want to die at home, not in a strange place … They calculate now that going to the slaughter peaceably has not diminished the misfortune, but increased it.”27

Many of the particulars in Mila 18 reflect details from the diary, beginning with the Good Fellowship Club, which is Ringelblum’s Oneg Shabbat group. Ringelblum is the model for Alexander Brandel, an amateur historian. In the novel, the smuggled report on the extermination camps is loosely based on one of the three similar reports compiled by Oneg Shabbat.

Of course, Ringelblum’s was not the only surviving journal of life in the ghetto. The journals of Chaim Aaron Kaplan, a teacher, and Stanslaw Adler, an officer of the Jewish police in the ghetto, are equally important. Mary Berg, the daughter of an American citizen repatriated in 1943, kept a diary from October 1939 to July 1942.28 Dr. Janusz Korczak, a noted physician, educator, and director of the orphanages in the ghetto, also kept a diary. His selfless act of accompanying two hundred children deported from Warsaw to Treblinka in the summer of 1942 remains one of the noblest acts of the war. He would not leave the orphans, choosing instead to go with them on the trains, holding the hands of two of his youngest pupils.29

Because it narrates a single cataclysmic event, Mila 18 is a more successful narrative than Exodus. In this work, Uris does not attempt to tell the entire history of the Jews; rather, it is the history of the Jews of a particular time and place, narrated with vivid details and action. Four parts organize the novel: the defeat of Poland by the Nazis; the organization of the ghetto by the Nazis and the awakening of the Jews to the Nazi reality; the slaughter of the Jews and the resistance; and finally, the epic forty-two-day battle. He also shows how communists, fascists, Zionists, collaborationists, and assimilationists in the Warsaw community could (sometimes) work together.

But Uris could not resist romance, an integral part of his formula for popular fiction. Here, it is the story of the journalist Christopher de Monti and the married Deborah Bronski, which competes with the graphic account of Jewish resistance. Foregrounding the story is Andrei Androfski, a Polish cavalry officer who knows that the only hope for the Jews is to strike back at the Nazis. His love is Gabriela Rak, an American Catholic who chooses to remain in Warsaw rather than escape. Again, Uris favors a Jewish hero with a non-Jewish lover (like Ari and Kitty in Exodus). He reverses this in the secondary romance: the non-Jewish de Monti and the married Jewish woman Bronski. To offset the partisan actions of Androfski is Alexander Brandel, a scholar, historian, and pacifist determined to save the Jews by not resisting the Nazis.

The novel, like Uris’s other books, is plot-driven, and action shapes character. Flashbacks are minimal, their absence creating a narrative momentum that drives the reader and the story forward. But Uris exposes the weaknesses as well as the strengths of his characters through their choices, which become moral statements. He relies again on a journalist to frame the story: here, Christopher de Monti takes the role played by Michael Morrison in The Angry Hills and Mark Parker in Exodus. De Monti, however, has a much more important role than his predecessors, alternating between apparent complicity with the Germans, especially with the propaganda specialist Horst von Epp, and commitment to his love for Deborah, sister of the heroic Androfski, but married to the sickly and morally paralyzed Dr. Paul Bronski. Androfksi is the Ari Ben Canaan of the novel, a Polish Jewish fighter extraordinaire.

De Monti’s recognition of his own moral complicity with the Germans leads to his heroic efforts to get a secret report on German concentration camps out of Poland and to escape so that he can return to Warsaw after the war and recover the secret archive stored throughout the ghetto. But he must give up his beloved Deborah, leaving her to her fate in the ghetto in order to convey to the world the history of the German atrocities, recorded and stored in boxes, milk cans, and other containers throughout the ghetto. He sacrifices personal happiness for history.

Of greatest importance to Uris was the theme of fighting Jews, first outlined in Exodus. His program was to liberate the Jews from the image of victim, coward, or willing prisoner. Uris expands his treatment of tough-Jew characters, finding in the ŻOB a turning point in Jewish history. David Ben-Gurion recognized this in mid-February 1943. On the day he and others honored the defenders of Tel Hai, a settlement in Galilee that fought to the last man rather than surrender, Ben-Gurion acknowledged the news of the defeat of the ghetto uprising but celebrated the Poles’ resistance and courage as a new example for all Jews of “heroic death.”30 The stereotype of the passive Jew of the Diaspora was erased, the uprising of the Warsaw Ghetto proof of Jewish valor.

The actions of the ŻOB confirmed Uris’s view expressed in an interview shortly after the publication of Exodus: “We Jews are not what we have been portrayed to be. In truth, we have been fighters.”31 For Uris, Jews were no longer ambivalent; history wouldn’t let them be. The Holocaust and the creation of Israel consolidated those tough Jews of the past, like the Maccabees. Warriors not rabbis became the new heroes, a transformation underscored by successes like the Six-Day War in June 1967 and the raid on Entebbe in 1976. Ariel Sharon replaced Gimpel the Fool. Masculinity, strength, and, if necessary, violence defined the new Jew. Passivity and weakness were gone, replaced by Jewish power. Uris knew the answer to the question posed by the character Jakov in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s novel The Slave: “Must a man agree to his own destruction?”32 For Uris, the answer was an unequivocal no.

In Mila 18, Uris takes up the theme of resistance with determination, although to his credit, he represents the controversy surrounding the decision to fight. When Alexander Brandel seeks Rabbi Solomon’s support in the novel, there is a lengthy discussion whether doing nothing or taking action is better for Jewish survival (M18, 136–138). Faith is not enough of a defense, Brandel tells the rabbi, and suffering is not salvation, as the novel proves. Androfksi and others attempt to convince the ghetto leaders that to resist is to regain dignity and infuse new meaning into being a Jew. They must fight to survive and to oppose the deportations. They translate into resistance the aged Rabbi Solomon’s view that God’s will is to oppose tyranny. This offers them the moral foundation for the violent defense of their world, despite facing overwhelming odds.

Uris’s writing also does battle, this time with history and sentiment. Too often he resorts to flourishes that compound cliché with excess. “Death spewed from the skies” is a simple example (M18, 89). Another: “Jewish guns vomited into their midst, spewing three years of pent-up rage” (M18, 476). His enthusiasm for action leads him to substitute rhetoric for style. A good deal of the novel also concerns the secret movement of individuals in and out of the ghetto, each crossing, of course, creating immense danger and the threat of immediate execution. Suspense is paramount, and when action occurs, it is presented dramatically and convincingly.

To maintain the narrative and prevent it from losing credibility amid all the impossible adventures and strained loves, Uris includes passages from a journal kept by Alexander Brandel, which was modeled on the work of Ringelblum (see M18, 114 or 277–281 for example). Balancing Brandel’s historical accounts of the slow destruction of Warsaw are the subjective experiences of those trying to survive in the ghetto. Military communiqués full of dates, locations, and military details also add to the objectivity of the narrative while forwarding the plot. The text even reproduces a telegram from Hitler authorizing the invasion of Poland, as well as various deportation orders (M18, 79, 312–313). Adolf Eichmann appears several times. The variety of narrative entries and historical figures keep the reader engaged despite the suffering and tragic nature of the overall situation.

Uris does not avoid the deprivation and pain of living in the ghetto. In fact, it is one of the most powerful and affecting features of the book. He writes vividly of starvation, interrogations, and battles. He even shows children being killed at whim, at one point a girl of three (M18, 359). But he also shows how the clever Jew can outwit the obtuse Nazis, as when the young Wolf Brandel is caught and questioned by the Nazi Gunther Sauer—and exhibits steely determination even when the beaten Rebecca Eisen, his contact, is thrown into his interrogation room and collapses (M18, 240–246).

Politics is also not forgotten. For the resistance to work, competing groups must cooperate. But unlike Exodus, in which Uris combined radical factions into a single group, Mila 18 maintains the independence of the differing units. But Androfksi, the leader, acknowledges the importance of cooperation if they are to succeed (M18, 269).

Despite the sensational aspects of the story, Uris resists showing the final destruction of the last fighters and the death of Androfksi or Wolf, the two final leaders. He does, however, provide plenty of violence, especially as the battle to destroy the ghetto continues, which creates such frustration for the Germans that at one point Oberführer Funk shoots one of his own officers in a rage (M18, 501). The German assault on the final bunkers of the resistance is dramatic (M18, 515–516). Deborah, who has devoted herself to protecting the orphaned children of the ghetto, dies in her brother’s arms. But Uris ends the story with the dramatic escape of de Monti and others through the sewer tunnels as characters romantically fight for their liberty: “Gabriela took a short barreled shotgun from inside her trench coat” (M18, 537). They must survive to reveal to the world the history of life in the ghetto, hidden in boxes and milk cans.

Mila 18 appeared while Eichmann was being tried in Jerusalem (June 1961), Uris capitalizing, again, on worldwide interest in the fate of the Jews. But unlike the tragic testimony and recounting of painful loss in the courtroom, Uris’s novel celebrates the courage of resistance fighters who, knowing they were in a hopeless battle against superior Nazi forces, did not give up or surrender. The battle against the Germans takes on almost mythic proportions. Mila 18, the address of the house that served as the command post for the fighters, assumes symbolic as well as historic importance.

Reception of the novel was strong among readers, weak among critics. Again, Uris was deemed melodramatic, accused of transforming a tragic story into an overheated account that favored emotion over fact. The New York Times, however, favorably compared the novel to John Hersey’s The Wall, claiming that Mila 18 was “authentic as history” as well as “convincing as fiction.”33 The Guardian took a different view, calling the book “nothing but a long sickening scream of anger and horror and racial pride.”34 The theatricality of Uris’s presentation undercut the suffering the novel should have dignified, while the dialogue approached only that of a B movie. There were also errors: Uris claims that the Jesuits led pogroms against the Jews in the Middle Ages, years before the order was formed; he places a Ferrari automobile in pre–First World War Italy, decades before the car company was formed (1947); he credits John Steinbeck with having written a section of John Milton’s Paradise Lost. There are also many grammatical errors and sections of sloppy writing. As one critic wrote: it is a failure as a novel, but a success as a manifesto of Jewish heroism.35

Mila 18 became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection and was so popular that the young writer Joseph Heller had to retitle his first novel Catch-22 instead of Catch-18.36 Uris’s name was becoming a brand, and his work was marketed as “Leon Uris’s new novel.” Titles almost became secondary to the promotion of the author, who could be relied on for historical detail, action, and, of course, romance. The novel spent thirty-one weeks on best-seller lists, and for Uris, its importance was clear: “If Israel was Exodus, Warsaw was Genesis—it was the first time Jewish people fought under the Star of David since the fall of the temple.”37

Uris, however, did not rest on the success of Mila 18. In May 1961, he began research on what would become his next novel, which would feature a military hero embroiled in postwar politics and the Cold War. For this work, to be called Armageddon, he traveled to Berlin, East Germany, and the Soviet Union. A set of slides from the trip records him flying into Moscow and includes photos of the Kremlin, a rally in East Berlin, and the Olympic Stadium in Berlin. Earlier, in 1958, he had had a photo taken of himself proudly crossing over into East Berlin and posing with a guard.38

The setting is again Europe, and the action takes the reader from the end of the Second World War through the first years of the American occupation of Germany and the Berlin airlift. The novel displays American courage, know-how, and determination, its patriotic author making it clear that America knew how to rebuild as well as fight. His unrepentant view of American power and expertise, despite communist threats and latent German hostility, persists throughout the book. In a later interview, he declared: “I really feel there would be no world without America.”39 In chronicling the career of Captain Sean O’Sullivan as a military administrator and an assistant to Brigadier General Andrew Jackson Hansen in the restoration of German cities, Uris blends historical detail with romance and politics while confronting the larger issue of redefining crime and punishment. The novel covers the transitional postwar period, when the Americans dealt with the remnants of the Nazis and guilt at their own actions while responding to the new threat of communism.

The Berlin airlift is the central event of the book, and in characteristic style, Uris undertook plenty of research. From the beginning of the project, he worked closely with the U.S. Air Force (USAF), which made archives available to him from its records center in Wiesbaden. Uris began by conducting on-site research. He had been to Berlin as early as 1958, when he went to meet the director assigned to film his second novel, The Angry Hills. Out of deference to the victims of the Holocaust, Uris had previously refused to travel to Germany but reversed his stand, treating his visit as a personal challenge. During a visit in 1961, he confronted communism when he crossed into East Berlin. But the East Germans were uncooperative and made it difficult for him to travel about and conduct his research.

The novel also gave him trouble partly because it was his most factually based work; the book stayed tied most closely to its sources. In seeking to re-create the postwar era, he seemed unable to release himself from his research. The consequence was a set of clichéd characters and staged events.

Uris’s access to USAF documents, some of which had been released only a few years earlier, hindered rather than helped the novel. His heavily marked copy of the two-volume USAFE and the Berlin Airlift, 1949: Supply and Operational Aspects indicates his attention to detail, much of which he incorporated into his story.40 This official history of the airlift supplied him with precise information on the number and type of aircraft, flight patterns, load factors, landing details, and estimates of needed supplies. It was invaluable.

The stopping of all passenger trains on 1 June 1948 between the western zones and Berlin was precisely the type of detail Uris loved, as well as the blockade of five coal trains bound for Berlin on 10 June 1948. He also underscored information on the removal of certain radio equipment from the cargo planes in order to increase their load capacities. Facts, figures, and charts added to the information. Of particular interest to him was the addition of a fourth squadron of thirteen C-54 Skymasters from the Seventh Air Force in Hawaii, which was ordered to Germany to bring European Command operations and spare crews up to full force. They joined aircraft from Alaska and the Caribbean.

Details on Lieutenant General Curtis LeMay, commanding general of the USAF in Europe, also fascinated him, especially the entry that on 29 June 1948, LeMay himself flew one of the C-47 cargo planes into Tempelhof airport and, while awaiting the unloading of his aircraft, held a conference with the theatre commander, General Lucius D. Clay. Uris loved specifics, such as the way coal from various German dealers was packed in U.S. Army duffel bags, each weighing approximately 50 kilograms, or about 110 pounds. Or the 9 July 1948 communiqué from the Soviets that their air force would undertake an indefinite period of instrument training in specified areas within the Frankfurt-Berlin corridor without filing any flight plans. The purpose, of course, was to harass the U.S. Air Force.

An overload of this type of information, along with nationalistic outbursts (“We have to love America the way our parents did,” shouts General Hansen [AR, 12]) interferes with the development of the novel, which opens almost a year before the end of the war. Plans for the rebuilding of Europe are underway, and O’Sullivan, promoted to major, develops a pilot project for a German city, the fictitious Rombaden. Uris then introduces an epic poem, The Legend of Rombaden, to partly explain the appeal to the Germans of establishing a master race and Nazism (some readers believed this to be an actual text; Uris made it up). It also contains the seeds of what O’Sullivan believes to be German anti-Semitism. Complicating matters is his natural hatred of the Germans because they killed two of his brothers in the war. Although he hates all Germans, he not only has to work with them but also falls in love with a beautiful German woman whose father was apparently involved with the Nazis.

A fictitious concentration camp named Schwabenwald introduces readers to the horrors of the camps. Determined not to let the Germans forget, O’Sullivan orders the residents of Rombaden to tour the camp before they are issued ration cards, as was done after the war at Dachau and other camps in Germany and Poland. Almost all the inhabitants of Rombaden deny knowledge of the camp. The anti-Nazi rebel Ulrich Falkenstein, recently liberated from the camp, challenges O’Sullivan’s attitude of Allied help, declaring, “I am a German and my first duty is not to Allied victory but to the redemption of the people”(AR, 94). The nobleman and Nazi sympathizer Ludwig von Romstein is his counterpart.

The novel focuses on a new threat, the Russians, which allows Uris to provide a good deal of Russian history in order to contextualize their presence. When O’Sullivan finally goes to Berlin, he understands clearly the new danger. Part II of the novel returns readers to April 1945, when the Soviets enter Berlin. Characteristically, Uris focuses on a few characters to represent history, in this case Bruno Falkenstein, the brother of Ulrich. The family’s story, a mixed account of sympathy with and distrust of the Allies, becomes a brutal retelling of Soviet atrocities and neglect. Uris then provides biographical notes on the new Soviet leaders, turning the novel briefly into a political textbook. The final third of the book pits the Americans against the Soviets in a battle for Berlin. The Soviets use various tactics and obstacles to prevent the American entry and redevelopment. Uris demonizes the Soviets and almost satirizes the Americans, especially in their belief that German self-determination will be strong enough to stop the Soviets, who turn to coercion and terror to maintain control.

Uris then turns to a journalist (again), Nelson Bradbury, to document the Soviet threat. If Berlin were to fall, all of Europe could come under communist control. As General Hansen states in a presentation to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, Berlin will be “our Armageddon” (AR, 460). Part 4 of the novel dramatizes the Berlin airlift, focusing on General “Crusty” Stonebreaker, who was modeled on General LeMay (General Lucius Clay was likely the prototype for USAF commander Barney Root). The crisis plays out against O’Sullivan’s love for Ernestine Falkenstein in overwrought prose: “Ernestine tried to touch him as he sweated and knotted with the pain of his dreams” (AR, 623). By June 1949, the airlift had succeeded, but O’Sullivan discovers that Ernestine’s father is a war criminal (AR, 604–605). Ernestine insists that O’Sullivan prosecute her father, although that means the end of their love. Again, as at the end of Mila 18, noble action supersedes personal happiness. In his grief, O’Sullivan realizes that he “cannot make peace with the Germans…. No real peace can ever be made until we pass on and the new generation of Americans and Germans make it” (AR, 625).

Structurally, the multiple stories and the quantity of political information distort Armageddon so strongly that its focus becomes unclear. Too many official reports entered as text further distract the reader. Some of the writing is visceral, as when a Russian general beats a Russian officer, but the sentimentality, which is strongest when Uris writes about relationships, undercuts the intensity of the action.

Doubleday did not concern itself with such matters, preferring to promote the book as superior to anything else Uris had written. Borrowing from earlier reviews, the ads trumpeted:

More “crammed with action” than BATTLE CRY

More “poignant human drama” than MILA 18

More of “a magnificent epic” than EXODUS

THE NEW URIS BESTSELLER TOPS THEM ALL!

ARMAGEDDON

A NOVEL OF BERLIN BY LEON URIS41

Within five weeks of its publication in June 1964, Armageddon had moved to third place on the best-seller lists. Its acknowledgments included support not only from various USAF officers but also from Columbia Pictures, which had funded his travel for a possible screenplay (the usual Uris scheme). And ironically, despite the impending breakdown of his own marriage, Uris provides a useful comment on love in the novel. The Soviet adviser Igor tells O’Sullivan, from whom he requests safe passage to West Berlin for his girlfriend, that love is “to know the faults and the wrongs of that which you love … and go on loving just the same” (AR, 610).

Uris proudly told his father that portions of Armageddon had been bought by the Saturday Evening Post after he had written only one-fifth of the book. He expected big things from its publication, and it did become a Literary Guild selection. But it is probably the least recognized of his books—“perhaps it was politically at the wrong time in the wrong place,” he admitted in an interview.42

Armageddon received unusually harsh reviews. William Barrett in the Atlantic dismissed it as “not serious literature but journalism…. His characters are flat and one-dimensional, as if already prefabricated to the Hollywood movie in which they are bound to appear.”43 Herbert Mitgang in the New York Times began his review with this sentence: “Leon Uris, one of the leading clichémongers of mass-cult, has constructed another of his non-fiction novels.”44 He then warns readers not spend the seven dollars for the book: “Mr. Uris’s latest epic is laughable as either fiction or nonfiction.” Furthermore, Uris was again following John Hersey, whose novel A Bell for Adano dealt more effectively with the American occupation of Europe. The Denver Post, however, saw the book as “a testimonial to the determination of the free world to prevail where oppression exists.”45 The rhetoric reflects the jingoistic tone and presentation of America in the novel, which the Chicago Tribune upheld: “Drama so intense, significance so great that the reader’s interest is caught at once and held to the end.”46

The novel sold more than 380,000 copies in hardcover, in itself a sort of answer to Time magazine’s scathing review, which started, “Hmm. Bank balance down. Time to do another Big Novel” and ended by noting that Armageddon “reads as if it were not written at all but dictated, Napoleon style, at top speed.”47 “Thank goodness I write for the masses and not for Time!” Uris responded. “They were wrong about Exodus too.”48 In the same interview, he remarks that he would soon be moving to Aspen, not because of the smog in Los Angeles but because he loved skiing.

Despite the negative views, the novel was an immediate best seller. Doubleday printed 85,000 copies to start and had 60,000 presold (mostly to the Literary Guild, its own book club). By November 1964, more than 310,000 copies were in print, the same month it was banned in South Africa because it mentions communism. Excerpts in the Saturday Evening Post generated interest also. Soon, it settled as number four on the best-seller list, after John le Carré’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, Candy by Terry Southern, and Herzog by Saul Bellow. Plans to film the novel, however, ran into delays and then postponement, as one paper explained: “His last novel, Armageddon was bought by MGM but it’s temporarily on the shelf because of anticipated production difficulties involved in re-enacting the Berlin airlift.”49

Uris capitalized on his appeal, however. In the mid-1960s, he negotiated a precedent-setting contract with Harper and Row, which gave him 100 percent (instead of the usual 50 percent) of all payments for paperback and book-club rights for his next novel. This would be for what would eventually become Topaz, a novel with as much intrigue in its origin as its plot.

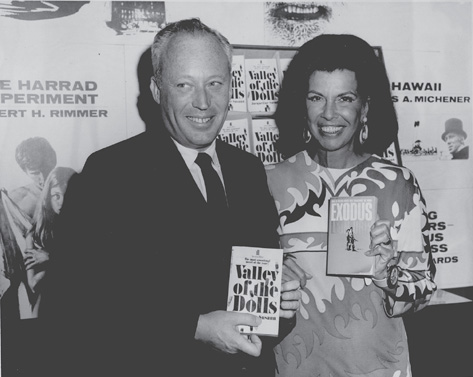

Uris and Jacqueline Susann promoting each other’s best sellers, ca. 1966.

Uris’s Russian family, including his father, William Wolf Uris (center, standing), his grandmother (seated), and two uncles, Aaron (wearing a hat) and Ari (wearing a white shirt). Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris in a studio shot at age four, 1928. Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris at age ten, January 1934. Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris (second from right) in Situation Out of Hand, performed at the Oak Knoll Naval Hospital, Oakland, California, 1944.

Uris in a marine trench coat, December 1944. The photo was sent to the parents of his fiancée, Betty Beck, with this caption: “He’s squinting dreadfully here—has blue eyes and nice eyebrows.” Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris and Betty Beck in their Marine Corps uniforms, January 1945. Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris and Betty in Clear Lake, California, December 1945 or January 1946. Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris standing in front of a car belonging to the San Francisco Call-Bulletin during his career as regional circulation manager, ca. 1952.

Uris signing copy of Battle Cry for a female admirer, 1953.

Uris in a Pittsburgh storefront with his arms around two marines, 1953.

Showgirl reading Battle Cry on the set of The Ed Sullivan Show, New York City, 1953.

Uris and Raoul Walsh examining the script of Battle Cry, 1954.

Uris with the cast of Battle Cry at the world premiere in Baltimore, 1 February 1955. Left to right: Uris, Dorothy Malone, Tab Hunter, Mona Freeman, and Raoul Walsh.

Uris and his children Mark and Karen with Burt Lancaster on the set of Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Hollywood, 1956.

Uris on the veranda of his home on Amestoy Avenue, Encino, California, during the writing of Exodus, ca. 1957. Uris is in his favorite writing outfit, including loafers without socks. Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Exodus cover, design by Sydney Butchkes, drawing by Harlan Krakowitz, 1958.

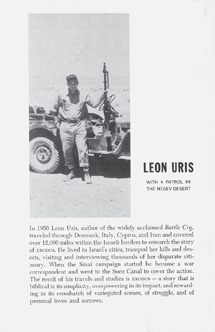

Exodus back jacket, showing a 1956 photo of Uris with a machine gun in the Negev.

Uris and Otto Preminger examining the screenplay of Exodus, Hollywood, 1958.

Uris at the Mandelbaum Gate, Jerusalem, 1960.

Uris in London during the 1964 libel trial that would become the basis of QB VII. Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris and Betty at dinner in Hamburg, 1965. Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris skiing, Aspen, 1966. Photo courtesy of Karen Uris.

Uris on the porch of his Aspen home while writing Topaz, 1966.

Uris and Margery Edwards, Aspen, 1968.

The stained-glass window in Uris’s library in his Aspen home, 1971. Photo by Jill Uris.

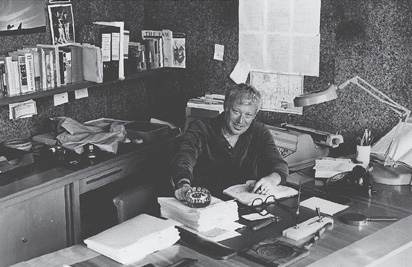

Uris in his Aspen study, 1972. Photo by Jill Uris.

Uris and Jill in Aspen.

Uris and Jill, Portland, Oregon, October 1981. Photo by Geoff Parks.

Gravestone of Leon Uris, U.S. Military Cemetery, Quantico, Virginia. Photo by I. B. Nadel.