CHAPTER 18

In January 1906, Ford Motor Company began a series of full-page ads that featured both the N and the K, one pictured under the other. For the former, the copy read, “This car—Model N—is the biggest revelation yet made in Automobile construction. A car of this type for less than $500.00 seemed an impossibility, but here it is. 4-cylinder—15 H.P. Direct Drive. Speed—40 miles. 78-inch Wheel Base. 700 pounds.” For the K, which ran underneath and appeared to be a gussied-up N, the copy read, “6 cylinders—40 H.P. 40 to 50 miles per hour on high gear. Perfected magneto ignition—mechanical oiler, 114-inch wheel base, luxurious body for 5 passengers, weight 2,000 pounds. Price, $2,500.00.” While certainly both cars were made to appear attractive, the N was presented as distinct and innovative, while the K was simply another luxury car in a virtually saturated market.

For example, also early in 1906, Packard phased out its own Model N and replaced it with the Packard 24. Priced at $4,000, it epitomized comfort, luxury, and the very best in automaking. “The motor has four vertical cylinders cast in pairs, with integral water-jackets and valve chambers,” Motor World wrote.

It is made in France from stock the best adapted to cylinder construction, but the machine work is all done in the Packard factory. The bore is 4 inches, and stroke 5 inches, so that there is an increase in the piston area over the model “N” of more than 20 per cent, and represents an increase in motorpower of 35 to 40 per cent, with only 5 per cent increase in weight. The pistons are fitted with four rings. For ignition an Eiseman high-tension magneto is used, although a storage battery is retained for the purpose of starting the motor from the seat, and is always in reserve. The magneto is bolted to the front arm of the motor support, and is operated by chain from a small counter-shaft, which is geared to the left camshaft. The current is carried through a single high-tension coil on the dash to the commutator. In the same box with the magneto coil is a single coil, with vibrator, for the storage battery, magneto and “open.” Individual switches connect with the stems of the spark plugs, so that a plug can be removed without disturbing the wires, or a fault in firing can be traced, by simply lifting one switch at a time.1

The Packard certainly cost a good deal more than the K, but it was also a good deal more car for the money. This is not to say that Ford was trying to sabotage his own product—he would certainly have been thrilled to sell every K he built. But it seems clear that the Model N was where he was placing his bets. To add to the sense of excitement, the early January Ford ads contained this postscript: “No further particulars will be given until these cars are shown for the first time at the Automobile Club of America’s Show at the 69th Regiment Armory, New York, January 13th to 20th. Deliveries for Models N and K will not be made before March. 1906 will be a ‘Ford Year.’ Agents who have closed with us can congratulate themselves.”2

But as had often been the case with Ford proclamations, Ford and Couzens were acting on a good bit of bluff, particularly for the N. To build a prototype to take to an auto show was one thing, but manufacturing ten thousand automobiles in a year—which is what they promised—was quite another. And they needed to build those ten thousand cars, for that was the cornerstone of their pricing. To defend their claims—which elicited serious skepticism, even disbelief, among automobile cognoscenti—Couzens took out a four-page ad in the January 1906 edition of Cycle and Automobile Journal. Under the heading “The Successful Ford,” the first page of copy read:

This is why we can build the Ford 4 cylinder Runabout for less than $500. We are making 40,000 cylinders, 10,000 engines, 40,000 wheels, 20,000 axles, 10,000 bodies, 10,000 of every part that goes into the car—think of it! Such quantities were never heard of before. For this car, we buy 40,000 spark plugs, 10,000 spark coils, 40,000 tires, all exactly alike. If we made a profit one-fifth as much on each car as is usually figured as a proper profit, we would make as large a gross profit as a manufacturer who builds two thousand cars. But who builds two thousand Runabouts? The first Runabout (Model C) we built cost $30,000, yet we sold duplicates of that model for $750. It is the quantity that counts.3

The ad went on to say that thousands were already in production, which was blatantly false, and that the Model N was a radical departure from previous Ford models, which was at least potentially true.

What was certainly true was that, despite the mythology that would settle around him only a few years later, Henry Ford at that point knew next to nothing about interchangeable parts, mass production, or even how to effectively set up a factory. He had squandered his chance to learn when he refused to even try to work with Henry Leland, and so, unless he could acquire those skills, and quickly, the Model N was doomed, no matter how good a car it was or how cheaply it was sold.

Although the car had to be “rushed through for the show”—it was completed only a few days beforehand—and had not been previously exhibited, “even to agents,” Ford, as promised, brought a prototype Model N to exhibit at the Automobile Club of America’s New York auto show that opened at 8:00 P.M. on Saturday, January 13, 1906, at the 69th Regiment Armory, at 68 Lexington Avenue. Opening at the very same time just steps away at Madison Square Garden was another automobile show, this one sponsored by ALAM. In a further attempt to choke off competition, the ALAM board had “suddenly and unexpectedly” made the decision in mid-1905 to no longer allow unlicensed manufacturers to exhibit at its annual auto show.4 Shut out of their industry’s most important trade show for the first time—the two sides had endured an uneasy coexistence at shows during the previous five years—the independents had been forced to scramble about, and the only appropriate venue they could find was the under-construction armory, which at that point was surrounded by scaffolding and crawling with masons, carpenters, and electrical workers. Like the Model N, the building in which the car would be exhibited was also “rushed through for the show.” When the ACA show opened, the scaffolding was gone, but large sections of the cavernous building lacked paint and other finishing touches.

The dual—or dueling—auto shows were, to that point, the most significant public display of the rift among automakers. While many buyers of automobiles had been at least vaguely aware that their purchase either conformed or did not conform to the Selden patent—and that Henry Ford was the most visible and outspoken refusé—the legal disputes had played out largely out of the view of the general public. But with automobiles attaining a popularity that would have struck dumb those who had watched the Chicago auto race ten years before, the stakes both inside and outside ALAM had escalated, and the battle had become plain to see.

“The makers of all the machines in the Garden recognize the rights of the Selden patent as covering the principles of the internal combustion engine, which is the scientific term for the gasoline engine,” The New York Times reported. “The armory exhibitors, on the other hand, are known popularly as the independents, as they have thus far refused to recognize the basic rights of the patent. This sharp legal division is really the reason for the two shows.”5

Each side billed its show as the “sixth annual,” dating from the first show in 1900. “Magnificent is the only word that aptly sums up the universal sentiment expressed last night by several thousand visitors to the two big automobile shows,” the Times went on. “If any spirit of rivalry were apparent, if any public favoritism had been anticipated, there were no evidences of such conditions in either the Madison Square Garden or the Sixty-ninth Regiment Armory.”

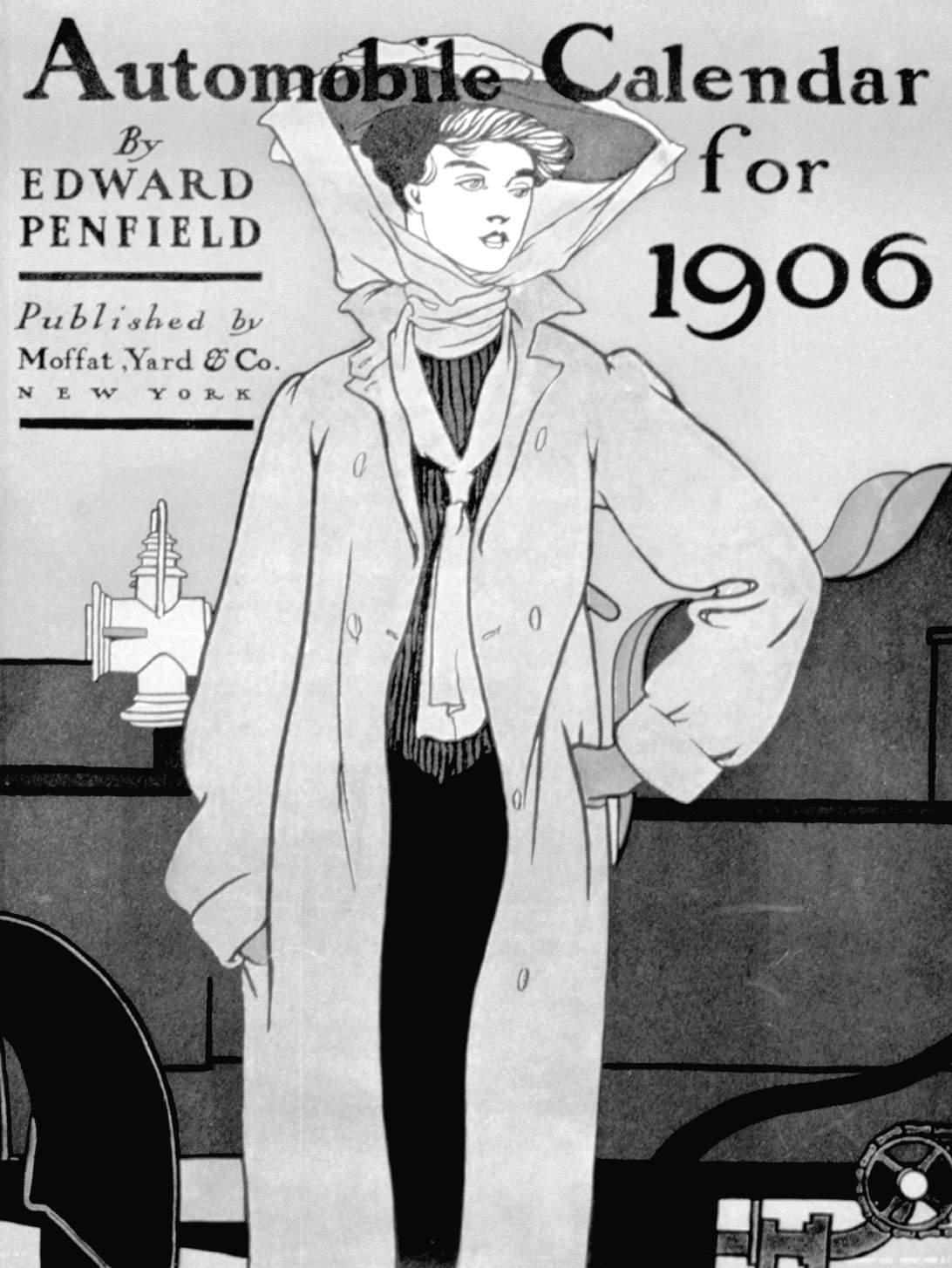

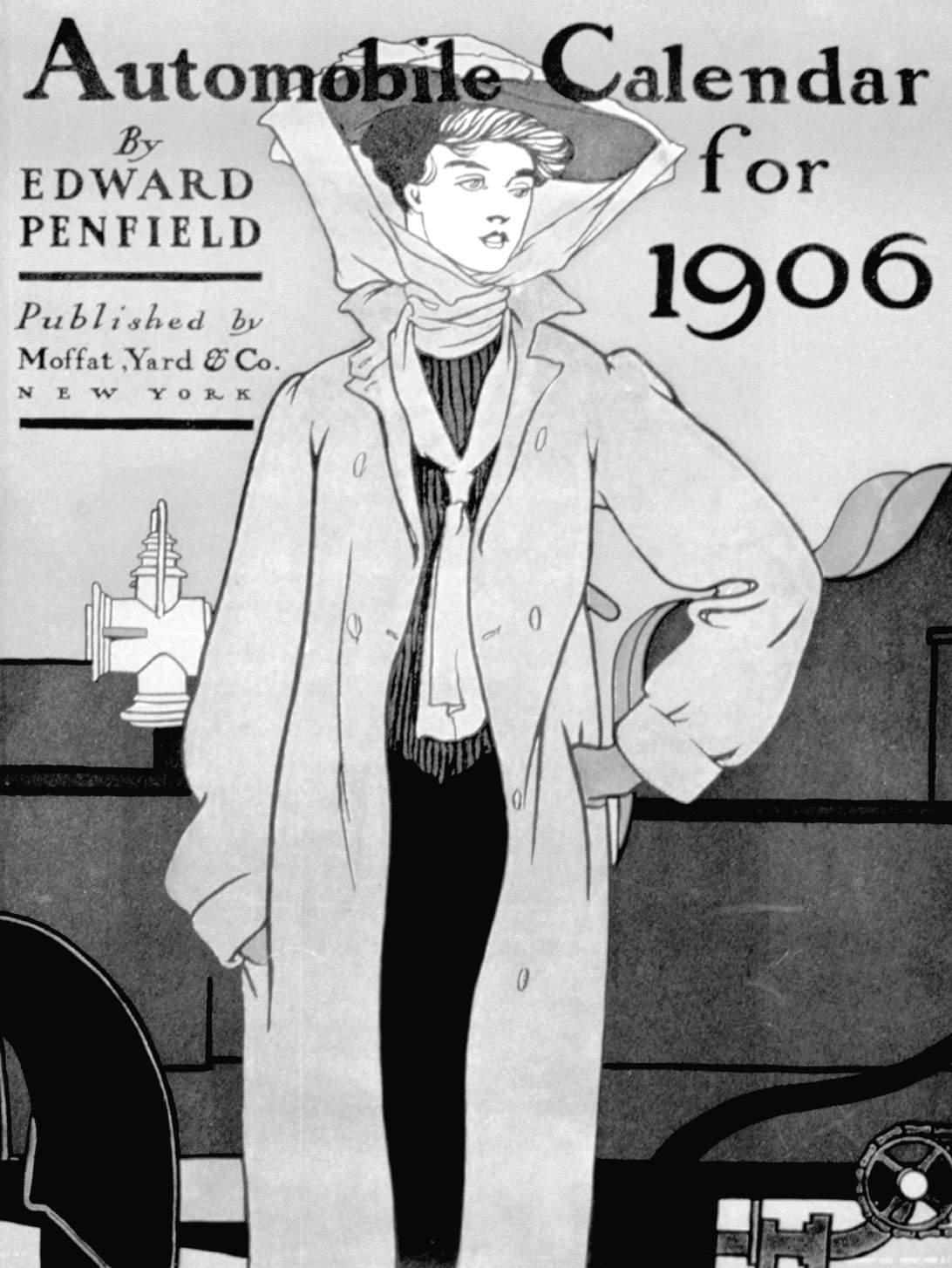

An automobile calendar for 1906, when cars became synonymous with glamour

But the trade journals saw things differently, and according to them ALAM had a clear advantage:

The Madison Square Garden show, held under the auspices of the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers, having the benefit of an old show building and the management of show promoters of many years’ experience, was as nearly complete as it is possible for a show to be on the opening day, and everything was cleaned up ready for the public. The Automobile Club of America’s show in the 69th Regiment Armory, not half a block away from the Garden, was not in the same fortunate condition, owing mainly to the fact that the building was still in an unfinished condition when the exhibits were installed and much new work had to be completed, so that although every exhibit was in place much cleaning up had to be done after the public was admitted.6

The ALAM board had, in fact, spared no expense, and their show could not be matched in opulence. “In appearance and effective decorations the Madison Square Garden show undoubtedly excelled anything of the kind which has ever been held, and persons who have visited the large building many times during the past 12 or 15 years, declared that never before was it so well planned or so magnificently decorated.” Thirty thousand electric lights had been mounted along the ceiling, potted evergreens lined corridors, and sculptures had been commissioned for the bases and tops of stairways. “The girders are hidden from end to end of the structure, and the ceiling has been transformed into a sea of blue, colored as an Italian sky, through which the dim gleam of hidden electric lights may be discerned, giving the effect of a clear night sky. Thousands of yards of cloth were used to gain this effect….Dazzling to the eye, artistic and beautiful, the huge building had been transformed into a veritable fairy palace,” gushed Horseless Age.7 The armory decorations, on the other hand, were described as “very neat and tasty.” If ALAM’s goal was to project solidity, prosperity, and trust in its products—and that automobiles were big business—it certainly succeeded. “One hundred and twenty pleasure vehicles of forty-eight different makes represented the Garden Show, and, remarkable as it may seem, there was not a freak among them.”8

But attendance at each show was, in fact, close to identical, with an estimated 95,000 attending the ALAM show and 85,000 visiting the armory. For all the expenditures and frills, it was the actual cars that people had come to see. Automobiles had become so much a part of the culture that the crowd “swarmed through the Garden, climbed into the various cars, played the gear and brake levers, tried steering wheels, peeked under bonnets and into the mysteries of the working parts…asked prices, talked carburetor, spark coil, gears and transmissions like old time veterans…It was a surprising revelation to hear young girls, and at times their younger brothers, talking automobiles and using the proper names for the various parts.”9 Reaction at the armory show was the same. And, as with any burgeoning technology, new products would attract particular attention, which left Ford with his revolutionary $500 runabout in a particularly favorable position.

Ford had brought a Model K—the lowest-priced six-cylinder car—and a Model F with him as well, but it was the Model N that drew the attention. And Ford’s runabout fared well, in terms of both its “decidedly pleasing appearance” and its specifications—described as “better at every point than was generally expected.”10 When Ford left to return to Detroit, he had assurances that thousands of orders for his runabout were soon to follow.

But the prospect of a clamor for the Model N did not make matters easier for Ford and Couzens, who were frantically trying to get the Bellevue Avenue factory in shape to actually produce their engines. And Ford wasn’t the only manufacturer who was trying to apply modern methods but had run into problems. “The demand for machine tools and automobile parts by competing companies was insatiable; and bottlenecks developed in half a dozen supply lines.”11

The operation Ford and Couzens encountered on their return to Detroit was indeed archaic, much of it reflecting manufacturing techniques already abandoned by Packard, Cadillac, and especially Olds. Certainly compared to George Condict’s battery-changing operation for the fleet of electric hansoms, Ford’s factory looked primitive. An engine block under construction needed to be passed by hand from one station to another, a process that continued until the completed apparatus was toted to the assembly plant on Piquette Avenue by the ever-trusty horse-drawn hay wagon.

As a result, the prototype that had been exhibited in New York had a number of problems that had to be eliminated—poor casting on the engine block and failures in the crankshaft and cooling system, among others—particularly before the company began to turn out one hundred identical automobiles per day. (Ford had been given a reprieve, however: because the Model N had been exhibited but not driven, its flaws passed largely unnoticed.)

But Ford once more proved that he knew not only when he needed help but also who could provide it and how to best avail himself of their talents. Setting up the Bellevue Avenue factory required heavy equipment, and in shopping for it, Ford had met a machine tool salesman named Walter E. Flanders, who also owned a small factory that made crankshafts. Flanders had previously worked for the Singer Sewing Machine Company, a pioneer in mass production, and Ford recognized instantly that Flanders was a man he should badger for advice. (In doing so, Ford again set aside his prejudices. Exceeding even Spider Huff in his appetites, Flanders was a hard-drinking carouser who was noted also as a brawler and an epic womanizer, all of which Ford overlooked in pursuit of product.) Flanders persuaded Ford to hire Max Wollering, a young engineer who was then working for International Harvester, and to give Wollering a free hand in setting up the Bellevue Avenue floor operation.

Wollering started work in April 1906 and immediately streamlined the workflow. “We put up short conveyers to push it along to the next operation. It was not automatic. It had to be hand conveyed. When the man finished the milling operation, he’d take the block, put it on the slide, and push it along to the next station.”12

Although the assembly line was still years away, with Flanders and Wollering, Ford finally began to add the refinements that could keep pace with Olds’s and Cadillac’s production methods. “We didn’t group our machines by type at all,” Wollering recalled. “They were pretty much grouped to accommodate the article they were working on….When I got there, they had the milling machine, which was very big, and the boring machine, which is large, in place. I left them stand and we built around them. We put the others in to make a kind of progressive arrangement.”

Standardizing the product flow made improving the actual product much easier. For safety and stability, the weight of the car was brought up from 700 to 1,000 pounds and the dimensions were increased to carry the weight.13 The crankshaft and cooling systems were improved, as was the casting of the engine block. By the time the Model N was ready to be examined by auto journalists, Ford agents, and potential buyers, it had been transformed and, at the proposed price, promised to be one of the most sought-after cars ever produced in the United States.

What received the greatest praise in the trades was Flanders’s and Wollering’s machining:

The feature that strikes the experienced manufacturer most forcibly is the care and accuracy of the work. Parts are ground that makers of high priced machines consider well enough made when done on a lathe. Cylinders and pistons are first rough cut, then annealed to relieve the strains in the castings, after which, in the case of cylinders, they are reamed, an operation that insures a perfectly straight as well as a perfectly round cylinder. This method is now considered superior to grinding by most engineers. Pistons, after being annealed are given a finishing cut on another automatic machine, after which they are ground. The top is ground four-thousandths smaller than the bottom end, the section between the first and second rings, three-thousandths, and that between the second and the third, two-thousandths smaller than the main portion of the piston.14

When Ford saw what Wollering was capable of, he put him in charge of the Piquette Avenue factory as well. Within two months, the operation was turning out a steady stream of automobiles—although nowhere near one hundred per day—so that Ford agents could begin taking orders for the Model N. Still, the N was not ready for actual sale until after Malcomson sold his stock to Ford on July 12.15

As good as Wollering was, Couzens knew that Walter Flanders was better. But Ford was reluctant. “Couzens, Wills, and the Dodge brothers were behind this selection,” Charles Sorenson wrote. “Ford…was aware of Flanders’s ability, yet feared the man might take his place. There was a streak of jealousy here. Flanders, a forceful, boisterous man, was popular with the directors and got along well with men in the shop.”16

But Ford never allowed personal feelings to keep him from talent, so, ultimately, he hired Flanders in August and made him head of production with complete control over manufacturing operations at both plants. Wollering and another talented young production man, Thomas S. Walborn, became his assistants. Flanders proved himself every bit as brilliant in his métier as were James Couzens and Harold Wills in theirs. Even more impressive was that Flanders often displayed his genius through the haze of massive hangovers:

He took on the Ford job and in a few weeks completely revamped the plant’s production methods. The whole interior of the factory was rearranged, new machinery installed, workers given new jobs. It was not assembly line production, which was to come later, but it was the most efficient production system that had been introduced in Detroit up to that time. In the final assembly, for instance, each workman had specific jobs to perform. Each group of assemblers had runners to keep material always on hand; and there were helpers who supplied small tools at the exact moment they were needed. There was no hit-or-miss assembly as there had been before. Everything was done systematically, and thus the job of putting Fords together was considerably speeded up.17

Charles F. Kettering, a noted inventor, engineer, and, for almost three decades, head of research at General Motors, was unstinting in his praise of Flanders’s brilliance.

Flanders’ specialty was simplification of work. He constantly shifted machines and equipment to minimize the handling of materials. He made each machine more adapted to a specific job by developing special jigs and fixtures to eliminate as nearly as possible the chance of human error. Not only did he rearrange production machines, but he used the principle of simultaneous machining operations wherever possible. He installed milling machines that could mill two faces of a casting at the same time, made other machines more automatic and set up scores of punch presses. All of these had been and were being used in the production of other things, but no one up to that time had brought all these production methods and machines to bear upon one model of an automobile.18

Sorenson summed it up: “In the nearly two years he was at Ford, his rearrangement of machines headed us toward mass production. Ford, a quiet, sensitive person, got a few gray hairs at this stage, but he learned a great deal from Flanders, and so did I.”*, 19

Flanders’s operation also had substantial impact on the way money moved through the company.

He found that the demand was in excess of capacity…and…set up a production program for twelve months ahead. This enabled the purchasing department to get better prices with fixed deliveries. Instead of our carrying inventories, he got the foundries and other suppliers to do it. Our stock keepers were told not to have on hand more than a ten-day supply of anything to meet our production requirements. Previously the funds locked up for this purpose had been very large. Now, thanks to Flanders, those funds were freed and much of the confusion of hand-to-mouth operation that Ford Motor Company had been working under was now ended. The results were a revelation to all of us.

Much of that money went into research, in particular for the next-generation Ford automobile, which in 1908 would be christened the Model T.

Literally one day before Alexander Malcomson left to build his “car of the future,” Horseless Age published an evaluation of Ford Manufacturing:

All parts, where it is at all possible, are finished on automatic machines, regardless of size. Each machine makes that part and nothing else; and since many of the machines are specially designed, they are fitted for nothing else. High-speed steel is used to its limit. A large corps of inspectors constantly follow the different operations in order to instantly detect any variation and rectify the error before it is made in a large number of pieces. For it will be readily seen that this system, which can only be applied where cars are made in very large quantities, cuts down the total cost of production enormously, and goes a long way toward putting the automobile in the same class with typewriters, sewing machines, guns and other interchangeable products.20

The piece then proceeded to praise the corporate vision that resulted in such a system, which went to the heart of Henry Ford’s brilliance:

In manufacturing any machine cheaply two distinct courses are open to the maker: Either he may use the cheapest possible material, make parts as small as he dares, finish as few surfaces as possible, and by employing cheap workmen and making fits so loose that the parts can be thrown together from a distance, he will be able to produce an article which will be cheap in more senses than one. On the other hand, he may use a quality of material amply good for the purpose to which it is put, design his machine so that the parts are as few and simple as possible, make them of sufficient size for proper strength and wearing qualities, and by systematized methods of manufacture finish all necessary parts as well as they need be finished. It is this latter course that the Ford Motor Company are endeavoring to follow in the manufacture of their little car.

By autumn 1906, while Ford would fall short of his goal of ten thousand cars (he would produce only eight thousand) and not be able to hold to the $500 price (he would raise it to $600), he had the best-running factories, which were producing one of the lowest-priced, highest-quality automobiles to be found anywhere in the world. Thanks to his own indefatigable efforts—and those of Alexander Malcomson, James Couzens, Harold Wills, Walter Flanders, the Dodge brothers, and a host of others—he had successfully transitioned from one of the hundreds of small, hopeful start-ups to an industry power; from an operation that threw automobiles together to one that used the incipient techniques of mass production.

With the N, Ford also demonstrated how his insatiable drive for improvement, his refusal to allow either himself or his company to stand still, could bear unexpected fruit. The Ford Manufacturing Company had been a contrivance, a paper fiction created to squeeze out an unwanted associate. If Ford and Couzens wanted to gain closer control over building engines and transmissions, there were any number of simpler ways to do it. But once Ford Manufacturing was a reality, Ford got the most out of it. Starting from scratch, he went out and obtained the human and mechanical resources required to initiate the manufacturing techniques that he would later be credited with inventing.