A horse with Cushing’s disease can live a comfortable life with proper treatment.

There are a great number of horse problems not caused by infectious organisms. Most of these diseases, such as heaves, laminitis, navicular syndrome, and muscles tying up, can be prevented by proper care. Other problems, such as allergies, cancer, or Cushing’s disease, are not as preventable; they may occur despite the best care and responsible use of the horse.

An allergy is a condition in which the body reacts adversely (locally or systemically) to a certain substance, called an allergen. Allergic reactions in horses can be triggered by many things, including environmental allergens (dust, pollen, molds), insect bites, substances in feeds, or injections of medications. Reactions may be localized in the skin and appear as swelling and redness at the site, or hives all over the body. Some reactions involve additional body systems such as respiratory and circulatory, and severe reactions may become life threatening unless reversed.

Sometimes the cause of an allergic reaction is obvious, if the horse was just given a drug or injection, or was recently fed dusty hay or given a new type of bedding, or you just started using a new fly spray or shampoo. The horse may suddenly develop a rash or hives after walking through nettles, for instance. Other times it can be difficult to pinpoint the triggering factor.

The first step in treatment for most allergic conditions is to try to eliminate the cause or avoid contact with the allergen. Often the best treatment for insect sensitivities, for instance, is prevention with use of fly sprays, protective flysheets, and so on. Sometimes antihistamines are helpful in treating seasonal allergies, but generally don’t work after the horse already has a problem. Severe cases should be treated with corticosteroids, which include dexamethasone given intramuscularly or orally, or a drug called prednisolone (different from prednisone). Corticosteroids are only available from your veterinarian.

Cancer is not common in horses, but it’s good to be aware of the possibility because many types are treatable in early stages. Benign growths enlarge slowly and rarely recur if removed. Malignant growths expand more rapidly and tend to spread to other parts of the body, infiltrating neighboring tissues or entering into the blood or lymph system.

A cancer can start from any type of cell (blood, bone, muscle), but more than half the cancers in horses originate in skin tissue. Most can be controlled if discovered in time and can usually be removed without major surgery. Some types of cancer are curable but only if they are detected early. Some kill the horse within a few weeks; others take years to cause death.

This skin cancer can occur on any dark-skinned horse, most commonly on grays. Melanoma tumors originate in cells that produce skin pigment (melanin). Melanomas eventually affect 80 percent of all gray horses over 15 years of age. Most gray individuals develop the black lumps in their old age. Because melanoma in horses is not as dangerous as in humans, only a few cases of these black lumps progress to the point of killing the horse. However, internal growths are fairly common in the intestinal tracts of older gray horses. You should suspect this if an older horse has chronic digestive or colic problems.

In mares, the lumps (tumors) usually develop under the base of the tail or around the anus or vulva. The nodules, which contain an excess of melanin, generally start out benign but may spread inward along the mare’s genital or rectal area, and the expanding growths in the pelvic lymph nodes can interfere with breeding and obstruct foaling. In male horses, the melanomas may develop under the tail but are often found in the sheath, sometimes giving the whole sheath a swollen appearance.

The black lump can be felt as a hard nodule in the skin. Not all bumps are melanomas; have a veterinarian take a look to be sure. Melanomas are usually smooth, raised areas without scabs or ulcers. Lumps may appear at any time after age 4 or 5 (but more frequently after age 15), and there may be few or many. Sometimes, a single large tumor appears on a young horse; this type of melanoma is likely to become malignant more quickly than those on older horses.

External tumors usually grow slowly and don’t develop into malignancy, but internal melanomas involve the lymph system and are more dangerous, often spreading to other parts of the body rapidly. Sometimes, a fast-growing melanoma creates a sore that won’t heal, pushing the skin apart. It may cause bleeding from the affected area.

Earlier thought was that melanomas should not be biopsied or removed, for fear of causing spread or regrowth, but many of these tumors can be successfully removed. Slow-growing external lumps are best left alone; they are unlikely to metastasize. If small growths start to change, they should be surgically removed before they become huge. Larger lumps or ones that start growing can be surgically removed if the horse is not showing clinical signs that would suggest malignancy. These are best removed if they might become a problem due to their location. Growths that may eventually impair a horse’s ability to urinate or defecate or may interfere with use of tack or breeding/foaling should not be ignored.

Other treatments include radiation, chemotherapy, and a relatively new technique called electroporation that involves using an electrical current to enhance the effects of chemotherapy. It increases permeability of the melanoma cells so that they either die or become more vulnerable to the effects of local chemotherapy. Some people treat melanomas with autogenous vaccines, created from tissue removed from melanoma growths on that individual horse. The surgeon can save some of the tumors removed, for the client to take to a lab that creates the vaccine.

Another skin cancer, this may appear on the eyelid and/or around the vulva or sheath if the skin is unpigmented. It is slow to metastasize, or spread. Intense sunlight damages the skin and makes it more susceptible to cancer. Because skin pigment helps protect against ultraviolet rays, dark-skinned horses rarely get this cancer. It is more common in horses with pink eyelids (Paints, Appaloosas, Pintos, horses with white faces, those with white markings on the face with pink skin around an eye, or light-skinned horses). Tumors near the eyeball in light-skinned horses are common in sunny areas such as California, the southern United States, and south of the border.

Because cancer of the eyelid can spread rapidly to nearby tissues, unless it is caught early you may need to remove the eye. Most squamous-cell carcinomas occur on inner parts of the lower lid or third eyelid and appear as a single raised bump or raw surface — a runny sore. The eye is irritated and waters. Not every bump or reddened area is a cancer, but if the abnormality becomes larger instead of healing and going away, or becomes redder or more irritated, the horse needs immediate veterinary attention.

Squamous-cell carcinoma can also occur on other unpigmented areas, especially those that are thinly haired, such as under the tail, around the mouth, or on the sheath. Check these areas periodically for any abnormalities.

The most common treatment is surgical removal. Other methods include freezing with liquid nitrogen, immunotherapy (injecting vaccine into the tumor tissue to stimulate production of anticancer cells), radiation, and hyperthermia (burning off the growths). When the cancer occurs on the eyelid, however, some of these methods pose a risk to the eyeball. Your veterinarian will choose a method that minimizes the risks.

A granulosa-cell tumor in the ovary of a mare causes problems with reproduction and disposition but is usually not malignant (although it can rupture, spreading cancer cells to other parts of the body). The granulosa cell is part of the ovary and produces the female hormone, estrogen. If this cell becomes cancerous, the tumor produces a mix of hormones, altering the mare’s hormonal balance and causing personality change and bizarre behavioral symptoms. She may become irritable, aggressive, or vicious. She may even show stallionlike behavior around other mares, especially if they’re in heat. Some affected mares tease and mount other mares. As the tumor grows, the mare does not come into heat and she cannot become pregnant.

Usually, the only effective treatment involves surgical removal of the tumor and ovary. Removal of one ovary does not interfere with the mare’s ability to reproduce if the remaining ovary is healthy. Most mares return to normal after the removal and start cycling again. If a mare shows a drastic change in behavior, have her ovaries checked. If there’s a tumor, it can be removed.

Other cancers in horses include abdominal cancer and cancer of the blood. Some are rare and difficult to diagnose or treat. Signs of cancer include any unusual sore or abnormality: a growing lump or bump, a persistent sore, bleeding or discharge from any body opening, chronic cough (other than heaves), or persistent weight loss. Abdominal cancer in an old horse may cause dramatic weight loss.

Lipomas are not really cancer because they are almost always benign. Consisting of slow-growing balls of fat on thin stalks, these fatty tumors in the abdomen occur most commonly in older horses, especially fat individuals. Usually, the tumor poses no problem unless the thin stalk becomes wrapped around an intestine, strangling the gut. In these cases, the horse will suffer colic and a fatal blockage of the gut (the stricture causes death of a segment of intestine) unless the condition is promptly corrected by surgery. Many older horses have a number of these fatty tumors, but only rarely do they cause problems.

The horse has a remarkable set of lungs that keep his blood supplied with oxygen. Anything that interferes with proper working of the lungs can limit his athletic or working career or compromise his health. A common problem that hinders a horse’s ability to breathe is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Called heaves by horse people, it occurs when horses are confined indoors or in dusty pens or fed hay that is dusty or moldy; it can also be caused by allergies.

COPD develops gradually and becomes worse, usually the result of prolonged feeding of dusty hay or an allergic reaction to hay dust, pollen, molds, or bacteria. A horse in a barn is more susceptible to heaves than one kept outside, as there’s more dust in the barn air from hay and bedding. Even an outdoor horse may get heaves if fed dusty hay because he constantly breathes dust particles as he eats.

Once a horse is sensitive to dust or molds, he relapses every time he breathes dusty air. Even if you keep him outside, he’ll cough if you bring him in overnight or to saddle him. If his problem is related to dust, he must be kept in a dust-free environment.

This chronic respiratory disorder is characterized by loss of ability to perform (exercise intolerance), constant or intermittent cough, and watery discharge from the nostrils. As COPD progresses, the horse loses weight and has labored breathing. Because the condition is not caused by infection, it doesn’t respond to antibiotics. Similar to asthma in humans, breathing difficulty results from narrowed air passages and an increased effort for every breath.

There’s a wheezing sound as the horse forces air out with two movements of the abdominal wall. Simple relaxation of the rib cage does not empty the lungs. The horse has to immediately follow it up with more effort, contracting his abdominal muscles and tensing his chest. In fact, many horses who suffer from COPD develop an enlarged ridge of muscle (heave line) along the lower side of the abdomen from overworking these muscles while forcing air out of the lungs.

Listen to the windpipe to check for wheezing sounds indicative of restricted airways.

Horses with COPD can be treated with drugs that open the air passages as well as with antihistamines. Your veterinarian can prescribe medication. The best treatment is to keep the horse in a dust-free place and never feed dusty hay. If he coughs when fed hay, use pellets; nondusty pellets are available for horses with heaves.

You can prevent heaves if you avoid dusty hay and bedding and keep horses outdoors as much as possible (unless the problem is from pollens outside). Horses with allergies are especially susceptible to COPD. If a horse tends to cough when hay is dusty, shake it thoroughly to get rid of the dust (but don’t shake it in the barn, as it will make the air dusty). Then sprinkle it with water to settle any dust that is left. For a horse with a serious problem, dunk each flake of hay in water (then drain it) before feeding, so it is absolutely dust free. A hay steamer can moisturize the hay even more completely, which can reduce inhaled particulates. Another option might be to switch to a pelleted feed or hay cubes, which tend to be less dusty than hay. The main approach is to reduce exposure to airborne particulates.

Bedding material should be as dust free as possible. Sometimes wood shavings are less dusty than straw.

Pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID), once called Cushing’s disease, sometimes affects older horses in their late 20s or into their 30s. Young horses are rarely affected. This disease is caused by excessive output of adrenal hormones from overactivity of the adrenal glands (found in front of each kidney), often in response to a pituitary enlargement.

Hormones are the signals that communicate between various glands and organs. In a normal horse, the hypothalamus at the base of the brain constantly reads the levels of certain hormones in the blood and then tells the marble-sized pituitary gland next to it to secrete more or less of certain types of hormones to keep things functioning smoothly. For example, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH, secreted by the pituitary) tells the adrenal glands to release cortisol. If the pituitary gland is secreting too much ACTH, the adrenal glands release more cortisol, which is detrimental to the horse’s body.

The adrenal glands secrete several hormones known as corticosteroids that affect the body’s use of electrolytes and glucose. These hormones also inhibit the immune system, a condition that slows the healing of wounds and results in lowered resistance to infection and disease.

The affected horse has an excess of hormones that raise the level of glucose in the bloodstream. This, along with the effect of the hormone on the kidneys, results in increased urine output; therefore, most of these horses drink a lot and urinate frequently. They may also have a shaggy coat that doesn’t shed, suffer from weight loss, experience chronic infection, or develop laminitis. They may become swaybacked and potbellied from loss of muscle tone. Diagnosis can be aided with tests for certain hormone levels.

There is no cure for Cushing’s disease; however, if the condition is diagnosed early, the horse can be treated with drugs to alleviate symptoms. The drug most often used is pergolide, originally used for treating Parkinson’s disease in humans. It replaces the missing dopamine that is not being supplied by the hypothalamus to regulate the pituitary gland. The horse must be treated for the rest of his life. The condition is eventually fatal, but treatment can help buy the horse more time and better quality of life.

Insulin resistance problems in horses are lumped under the term “equine metabolic syndrome” (EMS), a clinical syndrome association with laminitis in horses, first described in 2002. Not every fat horse is insulin resistant, but a fair number of them are and this creates health issues. Insulin resistance is defined as an inability of insulin to exert its effects on adipose tissue or glucose. Normally, insulin is released from the pancreas in response to increases of blood glucose concentration that occur following a meal that contains starch or sugar. The insulin allows glucose to move from the bloodstream into the body tissues. Because the glucose is leaving the bloodstream to go into the tissues, the blood glucose concentration in a normal horse goes down and then insulin concentrations go down as well. If the horse has insulin resistance, however, the insulin cannot open that “door” and the glucose does not go into the cells.

Signs of insulin problems include a cresty neck or abnormal fat deposits on the body. Most of these horses are “easy keepers” and tend to stay fat. The horse has higher insulin concentrations after eating, compared with a normal horse, which increases risk for developing laminitis. EMS and insulin problems are the most common causes of laminitis in horses and ponies in North America — much more common than laminitis that results from intestinal disturbances like grain overload. EMS may play a role in that cause, however, as an underlying predisposition for horses that overindulge in grain. Your veterinarian can test for insulin resistance by checking a blood sample to see if the insulin is high.

Managing the horse’s diet becomes very important. Most horses who are insulin resistant don’t need any grain. They may just need vitamins/minerals or a protein supplement.

Lush, fast-growing grass is also risky for these horses, since it is very high in soluble carbohydrates. EMS horses often develop laminitis (grass founder) when turned out on lush pasture. These are usually the horses and ponies who are easy keepers and tend to be insulin-resistant. Management entails avoiding starch/sugar in the feed, avoiding pastures rich in sugars (or using a grazing muzzle), and finding other ways to provide energy and calories in the diet than starch and sugars. Some complete pelleted feeds are very low in sugar and starch. You can also have your hay tested. If it has a lot of sugar, soaking it in water washes away much of the sugar. Soaking is more effective in some types of hay than others, however.

Exercise can reduce obesity, and having the muscles working improves insulin sensitivity. Horses who have laminitis, however, cannot exercise. If a horse is obese and insulin resistant, that horse needs to lose weight by cutting calories.

A healthy liver breaks down and filters out poisons, but occasionally in the process of protecting the body, it becomes damaged or infected, resulting in hepatitis, or inflammation of the liver. Both infectious and noninfectious, the disease can be caused by a virus, chemical or bacterial toxins, or poisonous plants. Primary liver disease is generally the result of poisoning. Secondary disease of the liver occurs as part of a generalized disease process in the body.

Toxic (noninfectious) hepatitis, usually caused by a poison in the body, can be acute or chronic. Acute hepatitis comes on suddenly; chances of survival are poor because the liver damage is so severe.

Chronic hepatitis occurs from toxins or poisons in smaller doses; it comes on gradually and may not be noticed until symptoms worsen. This can happen if the horse is eating poisonous plants or contaminated feed over time or has a bacterial infection that creates toxins, which, in turn, damage the liver. Early signs are dullness and lack of appetite. Pulse, temperature, and respiration are usually normal, but the horse may have abdominal pain that may be mistaken for colic and yellow mucous membranes.

Toxic substances are processed by the liver and excreted, but in a damaged liver, they build up in the bloodstream and affect the nervous system. Ultimately, the affected horse may stagger or drag his feet. His mental condition deteriorates. He may stand with feet wide apart and head drooping, or he may have muscle tremors. He may become so oblivious to his surroundings that he walks into trees or fences.

In some cases, the horse becomes violent and unmanageable, a danger to himself and anyone trying to handle him. He may have diarrhea, colic, or founder; he may also suffer from photosensitization (skin inflammation and sloughing in unpigmented areas) because his liver cannot filter out photosensitizing agents from plant material he has eaten.

Serum hepatitis (or “Theiler’s disease”) causes massive liver destruction. The virus is so hardy that chemical disinfectants cannot kill it.

Onset of symptoms is sudden, and the horse is almost always violent. He becomes mentally deranged and can’t be caught; he runs wildly, crashing into fences, walls, or other obstacles, and soon dies. This form of hepatitis is easily misdiagnosed as some type of neurological disease.

Serum hepatitis and rapid death of liver tissue are often the result of vaccination, occurring 30 to 90 days after the injection. A horse injected with vaccine or serum made from equine tissue or derived from horses may occasionally be at risk from serum hepatitis. Cases have occurred up to six months after injections of encephalomyelitis serum, tetanus antitoxin, pregnant-mare serum, and anthrax antiserum. About 90 percent of all serum hepatitis cases are fatal, with the horse dying within 12 to 48 hours.

Because of the risk for serum hepatitis, many veterinarians do not advise use of antitoxins, which have traditionally been used to treat or prevent a number of other serious conditions, except as a last resort. Several antitoxins are derived from horse serum (a possible source of the virus); the most widely used is tetanus antitoxin, often given for immediate protection against tetanus following surgery, foaling, or a wound.

Treatment with antibiotics, glucose, IV electrolyte solutions, and B-complex vitamins may be helpful in some cases of serum hepatitis.

Because it can be spread from horse to horse by use of contaminated needles, you should always use sterile disposable needles and syringes. Discard each needle and syringe after one use. Keep tetanus vaccinations current so you never need to use antitoxin. Be careful with chemicals that contaminate feed or water. Keep horses well fed so they won’t be tempted to eat poisonous plants. Check for toxic weeds in pastures, feed, and hay. (See chapter 11 for information on poisonous plants.) Keep horses healthy with good care and a conscientious vaccination program against possible diseases. Most cases of hepatitis can be prevented with good management and forethought.

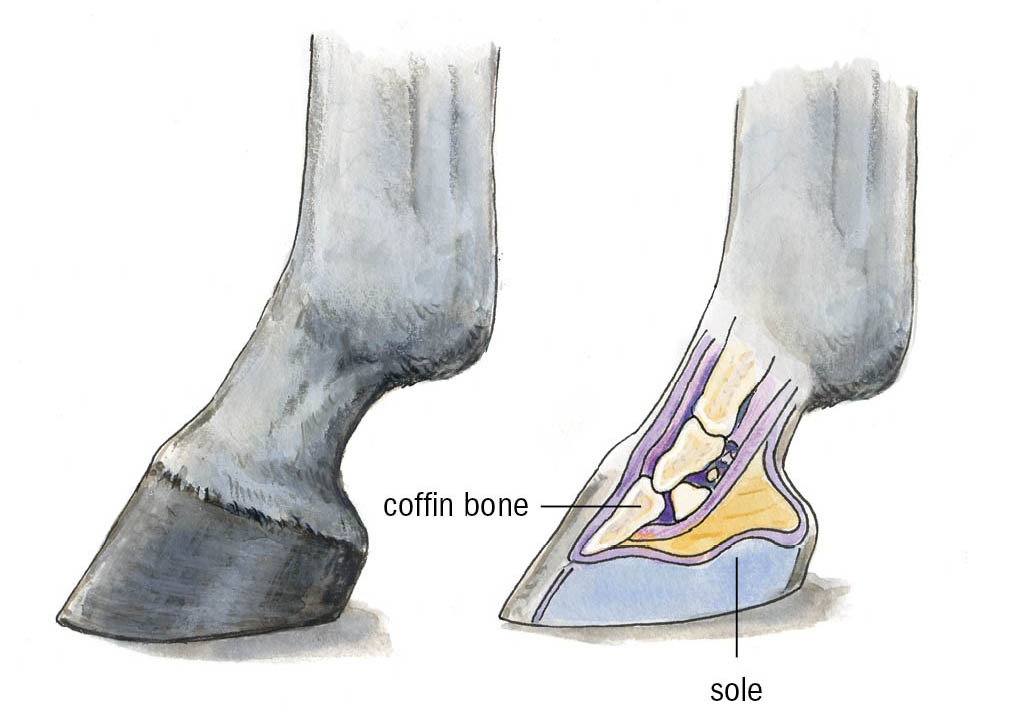

“Founder” is a term for changes that take place in the feet as a result of laminitis (inflammation of the attachments of the hoof wall). Bones and tendons of the leg terminate inside the hoof in an area that serves as a cushion and attachment between the inner tissues and the outer horny shell. When a horse suffers from a disease or metabolic problem that upsets his body chemistry, many changes take place that sometimes affect his feet.

A condition affecting blood circulation may not cause permanent damage in other parts of the body, but in the feet, which are encased in solid walls, there can be terrible pain and damage to the sensitive laminae. The tiny capillaries feeding the laminae are actually affected before the horse shows pain. By the time the horse’s feet become hot and tender, the damage is already done. The laminar tissues subsequently die, causing the hoof wall to separate from lack of support as the laminae give way and the coffin bone drops or (more commonly) tips downward at the front.

Pain makes it hard for the horse to walk; in severe cases, he reacts by lying down or rolling around. Lameness usually appears first in the front feet because they carry the most weight. Heat and pain occur in the hoof and around the coronary band. In acute cases of founder, there may be pain in all four feet, causing the horse great distress. He shivers, sweats, breathes rapidly and shallowly, and has a rapid pulse. He stands with all four feet bunched up under his body, back arched upward, and head hanging down. He doesn’t want to move. If he does, his gait is stumbling and shuffling because of the pain. It is hard for him to get up and down, and he may lie flat on his side for long periods, sometimes hours at a time.

Several things can cause laminitis, including grain overload, lush pasture, concussion from fast speed on hard surfaces, increased weight on the feet (such as constantly standing with all his weight on the “good” foot when he is lame in the opposite foot/leg), drastic changes such as drinking cold water when he is exhausted and hot and sweaty, infections, hypothyroidism, and complications (such as endotoxemia) from failure to shed the placenta after foaling.

Normal foot with healthy horn and proper angle.

Bacterial toxins in the bloodstream (which may occur with uterine infection from failure to shed the placenta after foaling, or when a horse overeats grain) are common causes of laminitis. When a horse eats too much grain, excessive carbohydrates in the hindgut stimulate rapid multiplication of intestinal bacteria. The microbes that ferment the lactic acid proliferate, using up so much available oxygen that anaerobic pathogenic bacteria begin to multiply rapidly. As they die, their endotoxins (poisonous substances in the bacteria that are released when the cell disintegrates) are released and seep through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream.

A foundered foot with rings and ridges and a rotated coffin bone. When a horse founders, the sensitive laminae, which bind the hoof wall to the coffin bone, lose their ability to hold the structures in place. With its anchor disintegrating, the coffin bone sinks downward at the toe, rotating toward — or even through — the sole of the foot.

Once in the bloodstream, endotoxins damage the smallest blood vessels. Tiny arteries clamp shut to conserve blood pressure, but this deprives the tissues of nutrients and oxygen. The terminal ends of the hoof’s arteries are especially vulnerable — the first victims of dying local tissue. As the horse’s blood-clotting system malfunctions, small clots form in many small vessels. As blood supply to the hoof is impaired, oxygen starvation causes excruciating pain followed by congestion and swelling. The laminae begin to die.

Even after the original cause of the condition has been corrected, the horse’s feet may become deformed if the laminae have become separated from the hoof wall and have allowed the coffin bone to drop or tip downward at the toe. The hoof wall spreads and develops rings and ridges, and the slope of the front of the hoof becomes concave. Sometimes, the separation of hoof wall is complete and the horny shell comes off. In this situation the hoof wall generally regrows, but the horse may need special shoeing for the rest of his life.

If you suspect laminitis, call your veterinarian immediately. Prompt treatment can help relieve the condition before the feet suffer founder — the changes in the foot that may follow laminitis. The veterinarian will treat the primary condition (such as grain overload, uterine infection) and give medications to alleviate the circulatory problem and reduce pain and swelling in the feet.

Using and caring for a horse wisely is the best insurance against founder. Always feed a well-balanced ration and introduce new feeds gradually over several days; never overfeed or allow a horse to overeat on grain or lush pasture. Condition horses to their work gradually, never work them to the point of exhaustion, and always cool a horse properly after a workout — gradually. Don’t allow an extremely hot and sweaty horse to drink very cold water until he is cooled out, and don’t put him away hot. Keeping a horse fit and healthy and giving prompt attention to any problems such as illness or retained placenta will help prevent founder.

“Navicular syndrome” is a term that covers a multitude of problems within the horse’s foot that were once all lumped together as navicular disease (problems within the navicular bone or bursa). This is a common cause of lameness in domestic horses but rarely affects the free-roaming equine. The practices of breeding certain horses with feet too small for body weight, using horses in inappropriate athletic activities, and keeping horses confined in unnatural conditions can lead to damage within the foot that may make the horse lame and lead to navicular syndrome. This is primarily a problem of front feet, because they are subjected to more weight and concussion than hind feet.

The small navicular bone lies deep inside the foot, above and behind the coffin bone, and serves as a pulley for the deep flexor tendon that glides along its underside and as a weight-bearing surface and shock absorber. It stabilizes the union of the coffin bone and short pastern bone, which are of dissimilar shape.

Anything that increases concussion to the foot, such as upright shoulders and pasterns, puts extra stress on the navicular bone and may lead to true navicular disease in which the bone itself (or its surrounding bursa) is injured. Jumping adds even more stress that squeezes the bone.

Often, the first step to diseased bone is poor circulation caused by clotting of tiny capillaries in the bone itself. Reduced blood flow weakens the structure; the bone begins to die. As it loses health and strength, it can’t bear weight properly and the horse suffers pain and lameness. Poor circulation may result from increased pressure (concussion, jumping, or working immature horses too hard) or from inactivity such as confinement in a stall. Standing in a stall reduces circulation in the feet and puts constant pressure on joint cartilages that are dependent on motion for blood circulation.

The navicular bone lies behind the coffin bone at the joint between the coffin bone and pastern bone.

Long toes and unbalanced feet also put more stress on the navicular bone, as does excessive body weight. A horse may have good foot and leg conformation and still have stress on that bone if he is kept in a stall with sloping sides, putting feet off level; the forces on the navicular bone as he stands on an upward slope are the same as if he had long toes and low heels. Navicular disease is often seen in feet that are too low at the heel, putting an extra squeeze on the bone between the deep flexor tendon and the lower end of the short pastern bone when the horse is standing. Pointing the foot forward relieves the pressure temporarily; a horse with a sore navicular bone often puts that foot forward.

Mild tenderfootedness is noticeable when the horse comes out of his stall. During early stages, the lameness diminishes with mild exercise, then gets worse if exercise is followed by confinement. Symptoms are usually not evident until the bone has already been seriously damaged. Lameness may appear in both front feet, but one may be worse than the other. Often, the first sign of lameness is obvious when the horse is turning or walking on gravel or rocks. He takes shorter, lighter steps, trying to keep the weight off his front feet. He gallops with a short, choppy stride.

During early stages, the lameness may come and go but, eventually, it returns and gets worse. The horse stumbles as he tries to put the toe down first and not take weight on the heel. Because of his shortened stride, you might think the lameness is in the shoulder instead of the foot. The horse may point one front foot forward when standing still to relieve the pressure. He may also shift his weight from one leg to the other. If the foot is unshod, it may be boxy, with high contracted heels, a worn stubby toe, and a small frog that is well up off the ground. If shod, the shoe’s toe will be excessively worn.

Normal foot (left) compared with a contracted hoof (right) caused by navicular disease.

The first step in treatment is proper diagnosis. Typical “navicular” foot pain may be caused by injury to the deep digital flexor tendon within the hoof, one of the supporting ligaments, or cartilage. Some of these injuries will heal with rest and treatment. Until recently, there was no good way to actually tell what was going on inside the hoof because nerve blocks, hoof testers, X-rays, and ultrasound can sometimes be inconclusive. Now a true picture of what’s wrong can be obtained using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and the horse can then be treated appropriately — and you’ll also know whether the horse has a chance to recover from whatever damage has occurred. Some of these problems can be treated and some can’t.

The best way to help a horse with actual navicular disease is to make management changes to halt the deterioration of bone. Nothing will return the damaged bone to its original shape and smooth surface, but changes in stabling and shoeing and new medical treatments can help. The horse whose circulation and hoof balance is restored will be more comfortable and more sound. Treatment varies with the severity of the condition. Anti-inflammatory drugs and arthritis medication or injections into the navicular bursa or coffin bone/navicular bone joint can help halt joint degeneration if the disease involves the joint.

In a severe and chronic case, surgery is an option to block nerves so that the horse feels no pain. This treatment is not without risk or possible complication. Your veterinarian should assess the horse’s condition and advise you on the best course of action. It is always better to prevent or halt navicular disease before it progresses.

Hoof care is important in preventing and controlling navicular disease and other injuries that can also cause foot pain. If shoes are left on too long, even a well-balanced foot will grow a long toe. For a horse with a serious problem, your farrier can use special shoes or wedge pads under the frog to give relief.

Muscle pain and cramping associated with exercise is fairly common in horses. The condition has had many names, including azoturia, Monday-morning disease, tying up, being corded, or being set fast. It involves painful cramping of the large muscles in the rump and, sometimes, the thigh and shoulders. Symptoms range from minor discomfort to collapse and death. The muscle cramping generally occurs during or after physical exercise such as a fast gallop or a long ride (or even running and bucking at liberty in deep mud or snow), but in some horses, there is a genetic defect in muscle metabolism and the cramping occurs even during mild exercise. It may also develop after stressful situations such as a fight with a farrier, frantic running during a thunderstorm, or a long trailer trip. Any muscle exertion beyond the horse’s accustomed activity can trigger tying up.

There are two types of severe muscle cramping: chronic and sporadic.

Chronic tying up occurs early in a workout or soon after exercise begins and is caused by inherited muscle abnormalities. This category can be further broken down into two distinct types: polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM) in horses with heavy muscles, such as Quarter Horses, draft horses, and warmbloods, and recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis (RER) in Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds, and Arabians.

Sporadic tying up can occasionally occur in any horse, most often after many hours of steady work and muscle fatigue. The causes and treatment/prevention are different for each type.

In these cases, the horse merely did something out of the ordinary: He may have worked too hard for his fitness level, for example, or strained his muscles, creating soreness. Dehydration from a long day of hard work in hot weather may lead to inadequate circulation to exhausted muscles. Putting too much cold water over the large muscles when the horse has been working hard may also cause cramping. These horses usually are fine if they are rested, and this type of tying up can be prevented by not overworking the horse beyond his abilities. Treatment in some cases may involve fluids and electrolytes if the horse has been worked too long and hard.

This inherited defect is most common in heavily muscled horses. When draft horses were commonly used, this was called Monday-morning disease because it generally happened after a weekend — the draft horses were grained heavily and worked hard all week, rested on Sunday, and worked again on Monday.

Muscle biopsy research has now shown that horses with PSSM accumulate an abnormal amount of sugar in the muscles and generally tie up if not getting regular exercise. They develop this problem early in life and are very sensitive to insulin; they can’t properly regulate energy metabolism in the muscles. This is because of a genetic mutation that probably occurred as long ago as the Middle Ages when people were breeding large, heavily muscled horses to carry knights in armor. These horses were the forerunners of today’s draft breeds. The genetic defect has now been found in at least 17 breeds, including draft breeds and their derivatives, Quarter Horses, Paints, Morgans, Tennessee Walking Horses, Mustangs, and Haflingers. There is now a genetic test that can determine whether a horse has PSSM.

Symptoms develop 15 minutes to an hour after exercise begins. The attack is sudden. The horse comes to a stiff halt, begins to sweat, is reluctant to move, and may want to lie down. The rump muscles are tight, stiff, and sore — similar to sudden thigh or calf muscle cramping in your own leg when you sprint or do something you’re not used to.

It may look like the horse has a urinary problem because of his stretched-out stance. If he can walk, his hind legs are stiff and dragging. The longer the cramp lasts, the more intense the pain because the muscle is oxygen deprived. The spasm squeezes the capillaries, hindering blood flow. There may be a peculiar odor to the horse’s breath, urine, and sweat from wastes excreted through the lungs, kidneys, and sweat glands; his urine will be darker than normal.

In mild cases, the symptoms disappear within a few hours if the horse is given immediate and complete rest and not moved. In moderate cases, the horse is anxious, trembling, very stiff, and reluctant to move; these symptoms may last from 24 to 48 hours. If pain is extreme, the horse will go down.

Prompt treatment usually relieves the muscle cramping. While waiting for the veterinarian, blanket the horse to keep him warm and relaxed, avoiding movement. Care for him where he is or take him home in a trailer and keep him on his feet. The veterinarian may treat him with tranquilizers, pain relievers, and muscle relaxants to increase blood flow and relieve spasms in blood vessels. He or she may also give vitamin E and selenium to help the muscles return to normal quickly. If muscle cramps are relieved in an hour or less, chances are good the horse will recover swiftly.

Horses with PSSM must be kept on a low-starch, high-fat diet. They should not be fed grain, sweet feeds, or molasses and should not be out on lush pasture. They need regular exercise, however, and should be kept in a large drylot with plenty of room, or a not-so-green pasture. These horses should be kept outside as much as possible rather than confined in a stall. Continual light exercise helps train the muscles to burn fat and also to access the excess glycogen to use as fuel.

Most horses with this problem are easy keepers and don’t need grain. They should never be allowed to get fat. Today, there are several low-starch/high-fat/high-fiber feed products that are designed for horses with insulin-resistance problems and these products also work well for horses with PSSM.

Recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis is another type of situation in which the horse ties up repeatedly, but it generally doesn’t occur until the horse is quite fit (as in race training) and it’s usually the nervous, young horses who are most severely affected. The tying-up episodes are often associated with excitement — young racehorses being galloped for exercise, fighting a rider who is trying to hold them back from full speed.

This is an inherited condition; certain family lines are more prone to this problem. The regulation of muscle contraction and relaxation is abnormal in these horses. Tying-up episodes can be minimized by careful management and allowing the horse regular exercise (turn out rather than confined in a stall). There is medication that can be fed daily to smooth out the erratic contraction of the muscles.

Diet management is helpful because many of these horses are more “hyper” and easily excited when fed a lot of grain. They tend to be very nervous animals and it’s hard to keep weight on them; therefore, owners generally feed them a large grain ration. It’s better to substitute fat such as vegetable oil or commercial high-fat supplements for part of the grain. This helps supply the energy they need without the extra grain. It also helps to keep the horse calm and reduce factors that may cause stress and excitement.

Headshaking syndrome in horses is a sign of disease (like a fever), rather than a disease in itself. There are a number of causes. The headshaking generally comes on suddenly in a horse who has never done it before and then continues to occur sporadically.

The horse exhibits a repetitive, involuntary movement that is generally more up-and-down than side-to-side. It is often a very quick downward flick of the nose, like something is bothering the horse. In serious cases the movement may involve the whole head and neck. It used to be thought this was a behavioral problem, and horses were often punished for it. Riders used running martingales, elevator bits, and special nosebands to keep the horses’ heads in position and prevent them from headshaking. Now we know it is a physical problem and not a behavioral problem.

Another sign of headshaking may include constant, vigorous rubbing of the head and muzzle — like a horrible itch that has to be scratched and nothing is making it better. Some of these horses develop sores from the vigorous rubbing. In some horses the sensation may be equivalent to that experienced by people who are sun sneezers. These horses can be helped by wearing face masks that help block out some of the sun’s rays.

Some horses respond to a nose mask that is attached to the noseband and fits firmly around the muzzle. The pressure it puts over that part of the face is like pushing against your nose when you have to sneeze and gives some relief from that sensation. Insect control is also important with these horses, because they are very sensitive to anything flying around their face.

There are other diseases of horses that you might experience; however, to cover all of them is beyond the scope of this book. Be alert to any unusual symptoms, and do not hesitate to contact your veterinarian if you think your horse has a problem. Some diseases occur only rarely, but the veterinarian may be able to help diagnose them and assist you with treatment.