CHAPTER 8 Plot II: Like a Roller Coaster

BY TOMMY JENKINS

Early on in John Ford's The Searchers (written by Frank S. Nugent), two girls, Debbie and her older sister Lucy, are kidnapped by Comanches after their parents are slaughtered. Their uncle, Ethan Edwards, sets out to find the girls, accompanied by the sisters' adopted brother, Marty. Ethan is played by John Wayne, and because it's John Wayne—the icon, the legend—we anticipate a heroic rescue. But Ethan is not a heroic man. He's driven more by his hatred of the Indians than his love for the girls.

The search takes years, turning into an obsessive quest. Ethan and Marty endure blistering nights of snow and scorching days with little water, hoping for just a hint of a clue as to where the girls are located. One day, Ethan finds Lucy's body and realizes she was raped before being murdered. His hatred and racism grow. Marty is pushed on by desire to save Debbie and bring her home. For Ethan, however, the mission changes to something more sinister. He's aware that as Debbie grows older, she too will be deflowered. She will become one of them. As Ethan says bitterly, "Living with Comanches ain't being alive." And he can't let her live that way. He'll kill her rather than let her become a Comanche.

After five years, the search leads to the Comanche camp where Debbie lives. Marty tries to save the girl, but Ethan throws Marty aside and chases Debbie down. She wears Comanche clothes, her hair is braided like a Comanche squaw. Ethan seizes her in his arms, lifts her high, as if he's going to smash her against the rocks and end it. But, in that moment, he sees the little girl he knew so many years before and the whole movie spins around with dizzying fury. Ethan brings her down gently, cradles her against his chest, and carries her off, saying, "Let's go home, Debbie."

Movies are like roller coasters. You climb that first hill—clickety-clack, clickety-clack—then swoosh, you are soaring downhill, then back up, then down, then twisting through a corkscrew, and so on. At times, you thrust your hands over your head, screaming with glee; other times you clench your eyes shut because you're scared to death. You're continually kept off balance, unsure of what's around the next bend. That's how you want your screenplay to work.

In this chapter, we'll examine three crucial aspects of plot—the lead-in, the second act, and the climax—that will help you create just such a ride.

The Lead-In

The first ten pages are considered the most important part of a screenplay. Now I'm sure you're asking, "The first ten pages? Really? Why are they is so important?" Think about it. Somebody in the business is reading your script. Probably this somebody has other scripts to read. Good chance this person has a whole stack of scripts to plow through in a weekend. And guess what? If they aren't grabbed by the throat in those first ten pages, they're moving on to the next script in the pile. There could be some great things to come, but they will never get to that dynamite moment on page 72 because you lost them on page 7. A great opening is equally critical to the finished film. So, even if you have millions of dollars and plan to produce your movie yourself, you better hook the audience during the first few minutes, because that's when they decide whether they like the movie or not.

Let's call the opening section of your script the lead-in. It runs from the first page to the "inciting incident," which usually happens around page 10—sometimes sooner, sometimes later. Instead of worrying about a certain page number, you can just think in terms of a great lead-in.

The lead-in should:

- Introduce the protagonist

- Establish the genre and setting

- Lead to the inciting incident

Not only do you have to accomplish those three things, you need to do it in a gripping way.

Let's start with the lead-in for Tootsie. Here's the first page and a half of the script. (I've made a few adjustments in the original script just to make it more closely resemble a spec.)

INT. ROOM - DAY

An actor's "character box." It contains: a monocle, different pairs of eyeglasses, rubber appliances, various makeups, a collection of dental applications, an assortment of brushes. A hand removes a small bottle. The other hand uncaps a bottle of spirit gum.

One hand applies the spirit gum to a cheek. The hands then apply spirit gum to a rubber scar, then place the scar upon the actor's cheek.

The ritual continues as a moustache is applied. The hands then search out the dental appliances and pick one. The appliance is inserted into the actor's mouth.

INT. THEATER - DAY

Blackness, or so it seems. Really a darkened theater. We're looking out toward the auditorium.

A VOICE

Next! Michael . . . Dorsey, is it?

MICHAEL DORSEY is looking out toward the darkened auditorium. He is an actor, forty years old, intense, focused, a man on a mission. He holds a script.

MICHAEL

That's right.

Michael's face shows the scar, the moustache, and perfect teeth.

VOICE

Top of twenty-three.

MICHAEL

(as a worldly man)

"Do you know what it was like waking up in Paris that morning? Seeing the empty pillow where . . . wait a minute, cover your breasts!

Kevin is downstairs! My God— what are you?"

A BURLY MALE STAGE MANAGER, cigar butt in mouth, stands near Michael, also holding a script.

BURLY STAGE MANAGER

"I'm a woman. Not Felicia's mother. Not Kevin's wife . . ."

VOICE

Thank you. That's fine.

We're looking for someone a little older.

INT. ANOTHER THEATER - DAY

Michael stands on another bare stage, beside another stage manager. He slings a yo-yo, dressed in cutoffs, T-shirt and sneakers.

MICHAEL

(as a little boy)

"Mom! Dad! Uncle Pete! Some thing's wrong with Biscuit!

I think he's dead!

ANOTHER VOICE

(from the darkness)

Thank you. Thank you. We're looking for someone a little younger.

Who do we see first? The agent? The roommate? Julie? Nope, nope, and nope. We see Michael Dorsey. We have to know whose story this is, who we are supposed to follow. And we need to know it quickly. Don't dilly-dally when introducing your protagonist. Get right to it.

And how do we see Michael Dorsey? In what setting? We see him putting on makeup and auditioning for parts. We see him as an actor. We see him in his world, the world of the movie. We also see that he is adept at altering his appearance, something that comes in handy later on. We sense that he is a perfectionist, that he takes his craft very seriously. And we see how desperate he is for a job, trudging from audition to audition, meeting only rejection.

It's also pretty funny. This is supposed to be a comedy, right? One moment, he's playing a love scene with a burly stage manager, the next moment he's trying to get away with being a little kid. You don't want people to be confused about the genre. You don't want them to get to page 10 and say. "Oh wow, I didn't know this was a western." If you are writing a western, we should see horses and cowboys in the first few pages. If you are writing a hard-boiled detective drama, don't make us wait to see that tough detective getting hired. If you're writing a comedy, give us something funny right up front so we know we're supposed to laugh.

In Tootsie, we get a strong sense of the protagonist, his world, and the movie's genre in only a page and a half. Talk about being efficient! All this information is revealed in a compelling way, too. There's something mysterious about seeing those hands apply the makeup. We're not sure exactly who it is or what's going on but we're curious. Then we get the humorous auditions. The lead-in requires some expositional information, but you need to deliver it as entertainingly (and visually) as possible. Think about the roller coaster. Riding up that first hill gets the blood flowing, the heart primed for what's coming.

Very often the lead-in shows us the status quo of the protagonist's life, the norm that will be upset by the inciting incident. That's what happens in Tootsie. We're getting to know Michael in his everyday world. But it doesn't stop there. Remember, screenplays are very compressed. Scenes have multiple functions. So while we're learning about Michael, we're also setting up all kinds of things that will figure into the story to come. Nothing is random in a screenplay. Every moment is there for a purpose. The subsequent scenes in Tootsie show us more of Michael and his world, while also setting up plot elements. We see:

Michael teaching acting classes (showing us he really knows his craft)

Michael haggling with a director (showing us why no one will hire him)

Michael working as a waiter (showing us why he's so desperate to have an acting job)

Michael discussing his roommate's play (showing us that he needs money because he wants to produce the play)

Michael attending his surprise birthday party (showing us he's not getting younger and that he's something of a cad with women)

Michael helping Sandy with an audition (for the role of the female hospital administrator on a soap opera)

With all of this information woven in, deftly and quickly, we are ready for the inciting incident. Remember, the inciting incident is a major event that sets the story in motion. Think of it as the peak of that first hill on the roller coaster. Once you start down that hill, the ride is on. If the lead-in has shown the status quo of the protagonist's life, the inciting incident will upset that status quo. That's what happens in Tootsie. Never forget that movies are not about business as usual. Movies are about life-changing events.

We could debate what the actual inciting incident for Tootsie is, but I say it's when Michael escorts Sandy to an audition for a soap opera and learns that Terry Bishop has been cast in a Broadway production of The Iceman Cometh. (It happens 16 minutes into the movie.) Michael flips out. How can that hack Terry Bishop get The Iceman Cometh? Michael was planning on getting that part for himself! (In a scene deleted from the movie, it's revealed that Michael and Terry used to be roommates, so there is a history of competition between them.) Michael is used to the humiliations of the acting business, but this isn't a typical rejection. This is the day he breaks. Not only does the inciting incident in Tootsie upset the status quo, it is also a breaking point. Michael has to do something drastic to change his life.

The news about Terry Bishop sets the whole story in motion. Michael bolts from Sandy, even though she's in despair, and makes a beeline to his agent's office to chew the guy out. His agent tells him that no one wants to work with him because he's too difficult. Furious and wounded, Michael decides he'll show 'em all. He dresses up as Dorothy, does a brilliant audition, and gets the role Sandy wanted on the soap. Michael landing the job is plot point 1. Remember, plot point 1 is a major event at the end of Act I that launches the major dramatic question. (For Tootsie: Can Michael maintain the masquerade?) Here's where the roller coaster throws us into a whiplash turn, sending things in a new direction.

Now, look, this turn of events wouldn't be the least bit believable if it hadn't been set up properly by the lead-in. But it's been set up so well we believe Michael Dorsey is desperate and talented enough to pull this off. And you know what? We also care whether Michael can pull this off. We've seen his struggles and we've seen his commitment. Without that lead-in, we wouldn't give a damn. This is crucial: We absolutely have to care what happens to the protagonist.

Not all movies need their inciting incident to be a big breaking point like the one in Tootsie. Both Thelma & Louise and Sideways are movies about friends going on trips. They're road movies. So, in both, we spend a little time getting to know the friends, Thelma and Louise, Miles and Jack, in their everyday worlds. Then the inciting incidents occur when they set off on the trips. As a result, the inciting incidents come sooner (9 minutes in Thelma, 6 minutes in Sideways.) You have to determine what kicks off your story. In a road movie the story usually gets under way when the trip begins. In a detective movie it's usually when the detective gets the case. In Chinatown, for example, the inciting incident is when Jake Gittes gets hired by Mrs. Mulwray to follow her husband. These aren't moments of drastic change, but the status quo is interrupted all the same.

Die Hard works a little differently because the status quo is a bit out of balance right from the start. The movie opens with McClane flying to L.A., leaving the familiarity of New York and entering a new world. He's clearly uncomfortable and nervous about the trip. We can tell from the start that he is not fully in control. Die Hard also waits longer than normal to hit the inciting incident (which happens 18 minutes in). But this extra time is necessary to establish firmly the relationship between McClane and Holly. This relationship anchors the movie, and they don't get to see each other again until the end. Die Hard actually has a very quiet lead-in for a fast-paced action movie. More often than not, action movies like to start with some kind of heart-stopping sequence to get you in that edge-of-your-seat mentality. Think of that rolling boulder in Raiders of the Lost Ark or the flashy opening of any James Bond movie. The leisurely lead-in of Die Hard is a risky move that ends up paying off very well. So, don't rely on convention. Find the lead-in that is right for your story.

The Shawshank Redemption shows us another variation, the lead-in providing a dramatic event that itself upsets the status quo. In the opening scene, Andy's wife is having an affair with another man and Andy is outside with a gun, drunk and ready to do something drastic. Then we jump to Andy's trial, where Andy is convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison. The inciting incident occurs when Andy enters the prison (which happens 10 minutes in). Because the movie is about a man dealing with the horrors of prison, we need to see how he is thrown into that world. We don't really get to know Andy in the lead-in, but that's because he is an enigma who will gradually reveal himself over the course of the movie. Again, the lead-in fits this particular story.

A story can start at any point in time, but you want to carefully choose the best place to begin. Think about what your inciting incident should be, then consider what needs to come before so the groundwork is laid. And make sure you get there as quickly as possible. If you're going to take longer than ten pages, you better have a damn good reason. You know that feeling of watching a movie and waiting impatiently for the story to get going. You don't want that to happen with your script. Get that coaster rolling.

Take a Shot

Watch a movie, any movie. List everything you learn about the protagonist during the first ten minutes. Also take note of how these things are conveyed on screen. (You can test yourself against our answers if you use one of the movies listed at www.WritingMovies.info)

Act II

The big monster. Act II. Sixty long pages staring you in the face. It's daunting. Probably the most intimidating section of your script. The second act is the place where many promising scripts run out of momentum.

You've got a lot to do in the second act. Or, to be more accurate, you should make sure you have a lot to do in the second act. After all, you have to fill up those sixty pages with something. And you have to make it dramatic. Okay, don't start hyperventilating just yet.

Here are five big tips to help you maintain excitement and tension in the second act:

- Keep the conflict coming

- Raise the stakes

- Weave in subplots

- Divide the act into quadrants

- Give it highs and lows

Conflict

Conflict makes a story dramatic. As long as you have conflict, you will have drama. Your first act should have given your protagonist a goal, a big goal. Your second act should show the protagonist in pursuit of that goal. And it's your job to toss as many obstacles as possible in his or her way. Once you start putting up those obstacles, you'll start filling your pages with good scenes. Conflict sustains your second act. Whatever form it takes—external, internal, spiritual, emotional, physical—you need to have conflict. Remember the roller coaster? The roller coaster doesn't reach the middle and become a steady ride. No, as you race along there are twists and turns and climbs and plunges and lots of surprises.

Take Tootise. We've got this guy who gets a job on a soap opera playing a woman, pretending that he himself is a woman. Now, in the second act, he must maintain that charade. He's good with makeup and he's a really good actor so he does pretty well with it at first. But this premise is going to have to sustain itself through the entire second act. How? Conflict. It just keeps coming. First, there's the conflict involved with maintaining his appearance. But you can spend only so much time showing a guy shaving his legs and plucking his eyebrows. So, you make it even tougher for him. He can't let his friend Sandy know because she'll die if she finds out Michael was the one who beat her out for the part and, to add more conflict, Michael sleeps with Sandy to cover the fact he was trying on one of her dresses. Then there's the lecherous ham on the soap who, wouldn't you know, takes a shine to Dorothy, Michael's feminine alter ego. And just so Michael can never catch his breath, Julie's father, Les, also takes a shine to Dorothy. All of these conflicts generate great scenes.

If you closely examine a character's goal, you should be able to create conflict in all kinds of places. Take the scene where the phone rings at Michael and Jeff's place. Simple thing, right? The phone rings. But Michael will not answer the phone because it could be the soap wanting Dorothy or it could be Sandy wanting Michael. If he answers as Dorothy and it's Sandy, that complicates things with Sandy. On the other hand, he doesn't want the soap thinking Dorothy has a man in her life. To top it off, he will not let Jeff answer the phone either. Jeff gets mad because people can't reach him at his own apartment. The conflict over being both Dorothy and Michael turns this situation into a great little moment about the struggle of maintaining these two identities.

That is what I mean by adding conflict. You don't miss opportunities to put your main character through the shit. It might be helpful to list every possible obstacle that your protagonist could encounter in pursuit of his or her goal. Nothing is too miniscule, not even answering the telephone. You probably won't use all of these obstacles, but you'll have them there whenever you feel that second act start to sag.

Raise the Stakes

Not only do you need lots of conflict, but you need it to escalate in the second act. Things must get progressively more perilous for your protagonist.

You accomplish this by raising the stakes. You hear this expression a lot. Somebody is always talking about raising the stakes, and how your script should raise the stakes in the second act. But what is it? Harvesting instruments of death for vampires? No, raising the stakes simply means that winning becomes more crucial, that the main character has more to lose, like when someone raises the stakes in a game of poker. Things get riskier for our hero, more treacherous. And your audience gets pulled more deeply into the story.

In Tootsie, the stakes get raised in two crucial ways. First, Dorothy's growing popularity increases the focus on her, which makes pulling off the charade more difficult. When Dorothy becomes a media star, she falls under greater scrutiny and there is greater chance she will be found out. If and when that happens, there will be hell to pay.

And then there's Julie. When Michael falls for Julie, it's no longer his career that's at stake. It's his heart. This opens him up to new obstacles, like spending time as Dorothy with Julie outside of work, even sharing a bed with her. At first the Dorothy disguise is a great way to get close to Julie but, after a while, it causes Michael unbelievable distress. He can draw nearer to Julie only as Dorothy, not as himself. As he falls in love, Michael's obstacles become more internal and decidedly more intense. Then there's the whole question of what will happen if and when Julie finds out about the masquerade. With Julie, the stakes are raised higher and higher for Michael. If he plays things right, he might get the girl of his dreams. If he screws things up, he may lose her forever.

In Thelma & Louise, the stakes are raised when Thelma robs a convenience store. They get the money they need, but now the girls are truly outlaws and the law is much less likely to view them with leniency. In Sideways, it's bad enough that Miles has to cover for Jack's infidelity to his fiancée, but the stakes are raised when he must lie about it to Maya, the first woman he's felt something for since his divorce.

Find ways to raise the stakes at least once or twice in your second act. Again, you might want to make a list. What could happen to make the rewards of the goal even greater? What could happen to make failure even more disastrous? You're bound to find answers that will lift your second act to new heights.

Subplots

You learned all about subplots in the previous chapter, so I won't say much about them here. But let me point out that subplots are a great device to help you get through the second act. Your main plot doesn't have to carry all sixty pages. You can sprinkle in subplot scenes here and there, like Jack's sexual hijinks in Sideways, or you can even take a subplot interlude, like the romances with Jimmy and J. D. in Thelma & Louise. Often Act II is where the subplots are dealt with most fully. In Tootsie, for example, the Julie subplot consumes a considerable portion of the second act. You've even got an 11-minute sequence in which Michael and Julie go upstate to visit Julie's dad, which is also where the Les subplot emerges.

Subplots offer a change of pace and allow for personal time with your characters, all the while serving as your ally when it comes to tackling the second act.

Quadrants

Still, damn it all, you've got sixty pages to fill. Sixty pages!

Relax, we have a way to break the second act down to make it more manageable. Let's call this the quadrant method. Now, obviously all sixty pages have to fit into the story, each of them coalescing into a seamless whole. But instead of having to think about all sixty pages at once, you can break it down into four quadrants.

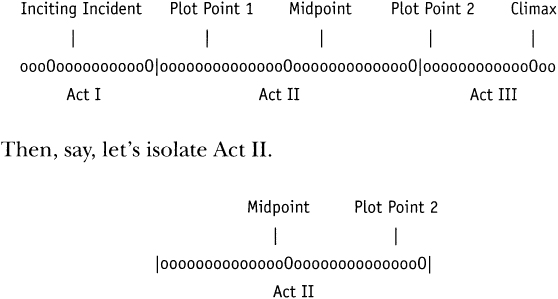

Let's use a visual. Visuals are nice, right? Helps us to learn. Look at this chart you saw in the first chapter on plot:

You'll notice right there in the middle of the second act is the midpoint. Remember, the midpoint is a major event that happens in the middle of the story. Often it takes things to a new level, giving a slightly different vibe to the second half of the movie. The midpoint gives you something to build toward in the first half of Act II, and something to work off of in the latter half of the act.

The midpoint is usually a high point, a moment when things are going very well for the main character. In Tootsie, the midpoint is the montage of photo shoots for Dorothy. Michael has achieved great fame as Dorothy. Heck, he's succeeded at fooling the American public. In The Shawshank Redemption, the midpoint is when Andy plays Mozart over the prison PA system. Here Andy finds a new level of personal freedom.

There are exceptions, of course, where the midpoint is not a high, but something calamitous. In Thelma & Louise, the midpoint is when J. D. steals the money. Before this, Thelma and Louise had the means to make it to Mexico, but losing the cash leads to Thelma robbing the convenience store and turning them into real criminals.

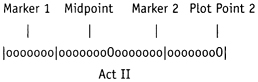

Okay, so the midpoint is a way to divide the second act into two halves, approximately thirty pages each. But it doesn't stop there. You can also divide the second act into four quadrants, approximately fifteen pages each. Fifteen pages is a lot easier to manage than sixty. Trust me.

So how do you divide the second act into quadrants? Glad you asked. You throw in markers 1 and 2.

Here's another chart:

In a screenplay these events usually fall approximately on the following pages:

Marker 1: page 45

Midpoint: page 60

Marker 2: page 75

Plot point 2: page 90

The markers should be significant events that affect the action in a negative or positive way. They're not as significant as the plot points and climax, but they're not chopped liver either. (Keep in mind that these page numbers are not set in stone. Most likely you will have some variation, five or ten pages on either side. Just think of the page numbers as rough guidelines.)

In Tootsie, for example, it breaks down this way:

Marker 1: Julie invites Dorothy over for dinner to run lines (46 minutes in). It's significant because it's where Julie and Dorothy start to move from being colleagues to being friends. This friendship will lure Michael into falling for Julie.

Midpoint: The montage of Dorothy's fame (57 minutes in).

Marker 2: Dorothy's contract on the soap is extended (77 minutes in). It's significant because Michael had expected to be done playing Dorothy, but now he's being forced into sustaining the masquerade for a year.

Plot point 2: Dorothy and Julie almost kiss (86 minutes in). A bond has formed between Julie and Michael, so much so that they almost kiss, but Julie pulls away, not wanting to get involved with a woman. Michael realizes that he can't have Julie as long as he's trapped in the dress.

Here's how the quadrants really help. Each quadrant springboards off the big event that preceded it, and then, after about fifteen pages, you've got another big event to springboard you into a new quadrant. It's like your story gets a shot of adrenaline every fifteen pages or so.

In Tootsie, the first quadrant springs from plot point 1, when Michael gets the job. So the main focus in the first quadrant is Michael dealing with his new job on the soap. Then comes marker 1, when Julie invites him to dinner, and this springs into the second quadrant, where the friendship with Julie starts getting layered into Michael's new double life. Then comes the high of the midpoint montage. This is a springboard into the third quadrant, where Dorothy grows more confident, so much so that she starts changing lines on the soap and, agrees to go on a trip upstate with Julie. Then comes the bad news of marker 2, when the contract is extended for a year, which springs into the fourth quadrant, where Michael starts to feel trapped inside Dorothy, culminating with the most frustrating moment of all, plot point 2, when Julie wants to kiss Dorothy but resists because Dorothy is a woman. Remember, plot point 2 is a major event that sends the protagonist toward the story's conclusion, and usually it's a real low point.

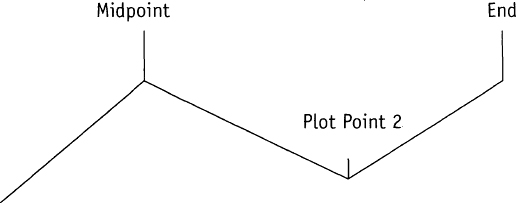

The High/Low Flow

Another way to ensure that your second act stays interesting is to make sure you're giving your plot highs and lows. You don't ever want to stop throwing obstacles in the way of your protagonist, but if things go nothing but bad, it'll grow tiresome. That's why you need to give your protagonist some victories along the way. Michael gets some genuine satisfaction playing Dorothy and he sure doesn't mind the fast track to intimacy with Julie that being Dorothy allows him. For all his troubles in Die Hard, even John McClane gets to yell "yippe kay yay" a few times. Think of the most depressing movie you know. I'll bet that even there, a few little good things happen.

In a larger sense, this is why the midpoint tends to be a positive event and plot point 2 tends to be a negative event. This is especially true of any story that is going to have an upbeat ending, as Tootsie does. We get a big overall swing from high to low to high again.

It looks something like this:

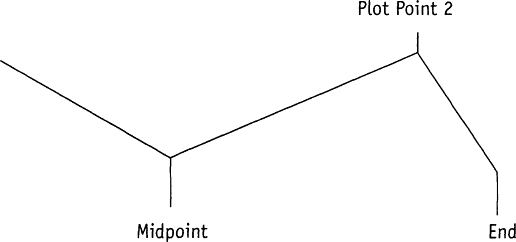

Now, if you have something of a downbeat ending, you very likely want a reverse effect so you still get the big swings from high to low. That's what happens in Thelma & Louise. At the midpoint, they hit their nadir when all their money is stolen. But then they start finding their groove as outlaws, finding liberation in their lives, which reaches a kind of high at plot point 2, when they look at each other as they drive through the desert, knowing they have found something they've long been searching for. And then, well, things go down at the end.

It looks something like this:

Damn, if those don't look like rollercoasters.

Take a Shot

Using the same movie from the previous assignment, list all the ways that the stakes are raised in Act II. (You can test yourself against our answers if you use one of the movies listed at www.WritingMovies.info).

The Climax

What is the most important part of your movie? The climax. "Now wait a minute, a while back you told us . . ." Nah, I said the first ten pages were the most important part of the screenplay. The most important part of the movie itself—the finished film we actually watch in the theater—is the climax. If the ending disappoints, everything that comes before is tainted. Hollywood ruins lots of endings by pandering to what they think are the whims of the mass audience, but that doesn't mean it's all right for your script to disappoint at the end. Nope, your climax better deliver the goods.

After all, this is it, baby. This is what the whole shooting match has been leading to. And you have to do it in a deeply satisfying way. Whatever is the most mind-blowing, stomach-plunging, heart-stopping device on your roller coaster, this is the time to use it.

The climax should do all of the following:

- Force the protagonist to take a final action against his or her biggest obstacle

- Bring about the answer to the major dramatic question

- Contain more dramatic punch than anything that has come before

The major dramatic question in Tootsie is: Can Michael maintain the charade? Throughout the movie, Michael has been juggling his two identities. But it's starting to drive him nuts. As Dorothy, he has grown close to Julie but after they almost kiss at plot point 2, he desperately wants to be close to her as Michael, which is impossible while Dorothy is still around. Things just get worse in Act III. Michael has had to fight off the advances of Julie's father, who wants to marry him, and Van Horn, who almost attacks him. Michael begs his agent to get him out of his contract, but it can't be done. Then, worst of all, Julie tells Dorothy that they can no longer be friends. Michael has to do something drastic. That's what you want to do, build momentum in this ramp-up to the big finish.

So what happens at the climax? Michael Dorsey reveals that Dorothy Michaels is really a man. To everyone. On national television. Live!

Michael takes this initiative himself; he is the one who rips off the mask. It wouldn't be right if someone had simply discovered his secret and reported it in the tabloids. Don't even think about using a deus ex machina, which is a fancy Latin term for a god coming out of the sky to save the day for the hero. And Michael is confronting his biggest obstacle here. What's the biggest obstacle? At this point it's his yearning for Julie, whom the disguise is keeping him away from. With Julie standing right there during the live broadcast Michael ends the charade.

That climax definitely gives us an answer to our major dramatic question. Nothing wishy-washy about it. We see that Michael can no longer maintain the masquerade. He can take it no more, not for another year, not really for another day. Not only does Michael out himself to his coworkers and Julie, he outs himself to the entire country. No doubt he'll be released from his contract after that. This is one of those cases where a protagonist willingly gives up the quest, and that's okay. But one way or another, the major dramatic question needs a definitive answer. Give us a yes or a no.

The Tootsie climax certainly packs a dramatic punch (Even literally so, when Julie hauls off and slugs Michael). What a great idea to have done it on a live show. Is it believable? Sure, within the context of this movie. It's been nicely set up. Earlier in the film, they had to retake a scene because a tech guy spilled celery tonic on the tape and we learn that this once caused them to do a show live. The tape guys screw up again and, boom, they have to do it live again. We buy it. And of course Michael makes the most of this moment, spinning an elaborate tale that seems straight out of Shakespeare.

Climaxes are usually very big moments. If you're writing an action movie, it better be the most intense bit of action yet. If you're writing a horror movie, it better be the scariest thing we've seen. You get the idea. But it's possible for a climax to be a very quiet moment, if your script calls for it. As in Sideways, when Miles has his breakthrough by drinking a valuable bottle of wine in a burger joint. In its own subtle way, Sideways fulfills all our requirements for a climax.

Here's the thing about climaxes: They have to encapsulate everything. During the climax, the goal and the obstacles come together in their strongest and most concentrated form, answering the major dramatic question in one bold stroke, and here the protagonist reaches the farthest point yet of his or her evolution. And because everything comes together at the climax, the screenwriter has to know all the points that lead you there. That's why it's good to know the ending when you start mapping out your story. You're already thinking about how the plot will come to a head at the climax.

In fact, the beginning of a story links directly to the end, and vice versa. The more you can make your story a complete sequence of linked events, the better it will be. Think back to that opening page of Tootsie. What was Michael doing? Applying makeup, applying a mask. In the first half of the movie Michael perfects the mask, something that peaks at that photo-shoot midpoint. In the second half of the movie, Michael learns enough from the mask so he doesn't really need it or want it anymore. What does he do at the climax? He rips off the mask.

Which brings us to resolutions. A resolution is a winding down, a chance for the audience to catch its breath before being thrust back into the real world. But it also has another function. This is where you tie up any loose ends and give a hint of the protagonist's future. Shouldn't take more than a couple minutes. Once you hit the climax, things should be just about over.

Take the resolution of Tootsie. Michael and Sandy act in Jeff's play, and Michael returns the engagement ring to Les, making peace with him. Then we get a hint of what might become of Michael. Time has passed. He seeks out Julie. Julie is angry at first, understandably so, but she finally warms up, asking Michael if she can borrow his Halston. We don't know for sure that Michael and Julie will become a couple, but we have a suspicion they will. As long as the MDQ gets a definitive answer, there can be some ambiguity in the resolution. It's nice to leave us with a little something to wonder about, giving us a sense that the characters live on after the lights come on.

It's not always easy to find exactly the right ending for your story. It must have been pretty tough to find the right ending for Thelma & Louise. Think about it. We've got these two wonderful women running from the law because one of them has killed a man and the other has robbed a convenience store. So they're hoping to get to the border of Mexico.

Couldn't they just get away? With half the cops in America chasing them? This isn't a fantasy movie. But we sure as hell don't want to see these women caught, handcuffed, and hauled off to jail. That would go against their journey of liberation. And we definitely don't want to see them gunned down à la Butch and Sundance. What about somehow reuniting them with the dopey men in their life? Forget about it.

What's a writer to do?

Well, in this case, the writer found the perfect solution. Their green Thunderbird is forced to stop when they come to the gaping expanse of the Grand Canyon. An armada of squad cars barrel down from behind them. An FBI chopper soars overhead like a gigantic hawk. In a glorious burst of liberation they hold hands and floor that Thunderbird into the splendor of the canyon. They die, sure, but they choose the way to go. And what a way it is. (There's no resolution after this because there ain't nothing more to show.)

Someone wise (maybe it was Aristotle) said an ending should be inevitable but unexpected. Inevitable means it needs to feel like the right ending, the place where things have been heading all along. But if it happens as we expect it will, then it's predictable, perhaps even a cliché. So the inevitable needs to happen in a way that surprises us, catches us off guard. It's a tricky thing to pull off, but it'll give you the best ending.

The ending of Thelma & Louise follows this advice. At the end of Act II, the two women are driving through the desert. They don't say much, but we sense what they're thinking. They doubt they will get away and they even suspect they may die, and they make a kind of peace with whatever lies ahead. In Act III, they act with abandon, as if knowing that these are their last days on earth. But I bet if you were watching that movie for the first time and I leaned over the seat and said, "Hey, do you know how this movie is gonna end?" I doubt that one of you would have said, "It's obvious. They're going to drive into the Grand Canyon." You may have known they weren't going to get away, but driving into the Grand Canyon? I don't think so. Unexpected. Big time.

Thelma and Louise fail to achieve their goal and, of course, it's heartbreaking, but there's also something uplifting about it. They have found peace, excitement, freedom. This is a destiny they embrace. If your story requires a downbeat ending, it's usually best if you can find a way to make it somehow uplifting at the same time, as long as you can manage it without resorting to something phony or saccharine. That way, members of the audience won't feel like driving off a cliff after they leave the theater.

Can you have a real downer ending? Something with no silver lining at all? It's very rare, especially in mainstream movies, because, honestly, a movie with a truly downer ending seldom makes money. But if a rock-bottom ending is what your story calls for, that's what it should have. As an example, check out Chinatown. Jake's love interest is killed, leaving Jake a shattered man, and the bad guy gets away, absconding with a little girl who happens to be his own daughter and granddaughter due to incest. Although it's exactly the right finish for that movie, there ain't nothing uplifting about the end of Chinatown.

Take a Shot

This one deals with your own movie. In prose, describe a nightmare dreamt by your protagonist. The essence of the nightmare will be the absolute worst thing that could happen to your protagonist in the pursuit of his or her goal. The primary obstacle should appear in some way. This is a nightmare, so push things as far as they can go, without worrying about plausibility. When you're done, see if there's anything in your nightmare that could be incorporated into your actual movie.

Flashbacks and Secret Tracks

Hey, before I go, why don't we discuss two more roller coaster-like techniques.

A flashback is when the action loops backward in time for a spell, and allows the viewer to witness events that happened days, weeks, or years before. Now that I've told you what they are, don't use them. Let me rephrase that: Some movies use flashbacks to great effect, but you need to be extremely careful with them or you'll jump your story off its track. As with voice-overs, you should avoid flashbacks altogether unless you have a strong reason for using them.

The big problem with flashbacks is that beginning writers love to employ them as an easy way to convey information. For instance, you use a flashback to reveal a character's history, their backstory. Or you use a flashback to clarify a plot point. Wrong. Way wrong. You should never rely on a flashback solely for purposes of exposition. That is lazy storytelling. If used in this manner, flashbacks will only slow the story down, killing momentum, and, perhaps worst of all, brand you as an amateur. It's your job as a screenwriter to convey the necessary information in a manner that keeps the story moving forward, not backward.

So when can you use flashbacks?

The most acceptable way to use flashbacks, and really the best way, is as a framing device, a way to begin and end the movie. You start in the present with a character and then we flashback to show this character's story, then at the end we return to the present. We've all seen this done. Think of Titanic. Starts with Rose as an old lady, a guest on an archeological ship in the North Atlantic, flashes back to her story on the Titanic, then returns to Rose on the ship at the end. (Actually we return to old Rose a few times in the middle, but only briefly.) The use of flashback enhances the story because we see how the tragedy of the Titanic has continued to ripple into the present day, and we experience a kind of peace at the end when Rose drops the necklace in the sea and dies. The tragedy of the story is tempered by this resolution. (A variation on this technique is to use a prologue, a short opening section that shows the characters at an earlier period in time, as done with the three boys in Mystic River.) But even as a framing device, you should use flashback only if it truly enhances the story.

If memory is a crucial element of your plot, then flashbacks may be a natural facet of the storytelling technique. But the story better really hinge on memory to justify the flashbacks. For example, in Ordinary People, a character is unable to escape the memory of a tragic death, and in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind a character is having his memory scientifically erased.

Otherwise, you should use a flashback only if it's absolutely essential and/or the most interesting way to illuminate what's happening in the present. Flashbacks are not about the past; they have to enhance the present story and move it forward.

The Shawshank Redemption earns its flashback on both these counts. The movie even dares to place it at the climax. When Tommy is killed, it seems Andy has no hope of getting out of Shawshank. He's in utter despair. Red fears that Andy will commit suicide, especially when he learns that Andy has procured a length of rope. When Andy doesn't come out for the nightly roll call, Red fears the worst. But then we see that Andy isn't dead. He's gone!

Whoa!

The way the movie is structured, the escape must be a surprise. Therefore, we can't see it happening in the present. If we did, no surprise. However, it's also the most triumphant moment for the main character, so we sure as hell need to see it. And once we see Red peering through that hole in the wall, we are dying to know how the heck Andy managed to break out. In a sense, we've been waiting almost twenty years for this. Accordingly, we see the escape in a well-earned flashback—Andy cleverly stealing the warden's clothing and money from under his nose, crawling through the tunnel then through the sewer pipe, emerging beyond the prison walls, lifting his arms as he's cleansed by the rain. This is an immensely rewarding moment, made all the more so by the way it is revealed.

This brings us to our other technique, the secret track. What's that? Well, the secret track is a layer of the story kept hidden until the end, and when it's revealed we view the entire movie from a new perspective. You'll find brilliant secret tracks in such movies as The Usual Suspects, The Sixth Sense, and Body Heat. Shawshank has one, too: Andy's escape. We have no clue that Andy has been planning an escape until he has actually done it, and when we learn about the escape, Andy's journey takes on a new dimension for us.

Secret tracks are always a surprise, but they should be a satisfying surprise. It's difficult to pull off, requiring very careful plotting. The audience should be able to look back at the rest of the movie in the light of the secret track and see that everything makes sense, and yet you have to set it up without revealing too much, without giving away the surprise. It's like taking the "inevitable but unexpected" rule to the nth degree. In Shawshank, for example, we see Andy carve his name with the rock hammer into the wall. But we never suspect he's planning to tunnel with the hammer because we know he's a rock hound and he wants the hammer only for carving chess pieces, which he does. Besides, he even makes a joke about how it would be impossible to tunnel out with this tiny device. When it happens, however, we believe the escape, because by then we know that such a thing is not impossible for a man like Andy Dufresne.

You shouldn't attempt a secret track unless your plot calls for it, but if you can pull one off, you'll turn the story into a truly unforgettable ride.

Stepping-Stone: New Beat Sheet

Create a new beat sheet for your movie. This time include subplots, and factor in everything else you have learned since writing your first beat sheet.