CHAPTER 11 The Business: Slipping Past the Velvet Rope

BY CHRISTOPHER MOMENEE

Here's the scene: An aspiring screenwriter is printing out a script in a crowded NYU computer lab (thanks to the bogus validation sticker he's glued on to his old student ID). Someone enters, calls out his name—mispronouncing it as everyone does—declaring that there is an urgent phone call for him. Fearing a family emergency, he rushes to the phone. It's his writing partner on the other line. "Get home now!" he shouts. "This thing is going down! Disney wants to buy Kid!"

The writer runs the six blocks to his apartment in the East Village of New York City, visions of a sugarplum deal dancing in his head. He imagines attending the premiere of Kid at Mann's Chinese Theater on Hollywood Boulevard, doing the red carpet crawl with a budding starlet he'd met in the lounge of the Four Seasons the night before, pausing for flash-bulb-popping paparazzi, and sure, what the hell, maybe a few words for Entertainment Tonight. His heart pounding, the writer charges up the three flights of steps, fumbles for his keys, bursts through the door and gets on the phone with his writing partner in Jersey and their entertainment lawyer in midtown.

"Hey, guys, we have a good news-bad news situation on our hands," the lawyer says. "Good news is, Disney really likes your script."

The writer flashes on Elijah Wood for their main character. Wait, he may be too old already. What about Haley Joel Osment? Too young?

"In fact," the lawyer continues. "They want to buy it . . . for mid-six figures."

Holy shit! This is like Lotto money. More money than he's ever dreamed of making in one fell swoop.

"What's the bad news?" the two writers ask, wondering what could possibly be bad news after that.

"Well," the lawyer says with some reluctance. "They want to bury it."

The writer's mouth falls open. Wha . . . ?

This is a true story. It happened not so long ago to my writing partner and me. Kid was my very first script sale, a family action/ adventure about a young boy who befriends a King Kong-size "kid" gorilla. Basically E.T. in a gorilla suit. At the time, as it turned out, Disney was developing a remake of the 1949 movie Mighty Joe Young—also featuring a gargantuan gorilla—and wanted to make a "defensive purchase" that would take our competing script off the market. (For what it's worth, word leaked out that some executives liked our script better.) Right then and there, with the lawyer on the phone, we had to decide whether to accept the deal Disney had put on the table, or take our chances and hope that another studio would make an offer, and then make our movie. So we did what most fledgling writers would do in our position—we took the money and ran like hell.

The sale was never posted in Variety or the Hollywood Reporter with their patented industry-speak that makes you feel oddly legit, like DISNEY GOES BANANAS FOR "KID" SPEC OR MOUSE NETS APE. There was no mention anywhere. Nada. The sale was buried like our script. It was as if we'd been paid with hush money. As we soon learned, a defensive purchase is standard practice in Hollywood. The studios spend millions every year on scripts they don't necessarily intend to make, often just to prevent another studio from potentially spinning them into box office gold.

It's a mad, mad, mad, mad business. You hear about the producer with a hair-trigger temper who throws phones at his assistants; the starlet who locks herself in her trailer after discovering a pimple on her chin; the screenwriter who comes onboard a project after eleven before him have been dismissed. With so much money riding on every project, so many egos vying for power and control, so much paranoia and glamour and hype in the mix, madness seems a prerequisite. Is there any other business, besides maybe gambling, where fortunes are made or lost in the span of a single weekend? Careers launched or grounded by a single project? And while a critically acclaimed film may bomb at the box office, a brainless teen movie might stay number one for five weeks in a row. It's inexplicable. It's mad. It's a world where, as the master screenwriter William Goldman so famously proclaimed, "No one knows anything."

It's also a world that is extremely difficult to enter. Think of it as an ultra-exclusive nightclub decked out with palm trees, lily ponds, and maybe a few exotic women swinging from trapezes. You saunter up to the entrance, but are quickly stopped by the 300-pound bouncer standing guard at the velvet rope. You look past him and see all these clubbers having a great time inside—dancing, laughing, sipping cocktails. But unless someone on the inside has put your name on the list, you don't have a snowball's chance in hell of getting in. That's what it's like being a new screenwriter. Standing in front of an exclusive club, proudly clutching your new spec script, hoping that someone has put your name on the list. Odds are, your name's not there. You may have to wait a long, long time. You and the hundreds of other screenwriters standing in line with you.

But while it may be tough getting into that club, it's not impossible. This writer did it and I assure you he's just an ordinary guy from Toledo, Ohio, home of Jeep, the Mud Hens and the Maumee River. So why don't I tell you what I know about slipping past that velvet rope.

Preparing the Script

You might be thinking, Why should I waste all my time and talent writing an entire script when I can just come up with an irresistible idea? Isn't that what they want anyway? A pitch for a potentially huge hit? Or maybe a pitch for a breakaway indie that could capture lots of awards? No. Not now, anyway. Almost never will the decision-makers in the business indulge a pitch—without a script—from an unestablished writer. Great ideas in Hollywood are like brass fasteners. Everyone has hundreds of them. You have to show them that you can write, that you can make that great idea come alive in a fully developed, winning script.

Let's say you found your great idea. Or it found you. You outlined it, wrote that sloppy first draft, and now, some thirteen drafts later, you have a killer spec on your hands. Yep, it's all there; it moves and is moving. It's a movie. You've given birth to your bouncing million-dollar baby.

So, with the creative work done, it's time to concentrate on the business side of this endeavor. You're essentially changing hats from Writer to Salesman, viewing the spec not as your "baby" anymore, but as your widget—a product you would now like to put on the market where it becomes the object of a bidding war, finally bought by a major studio for a small fortune, and ultimately made into a hit movie for all to see.

If your widget's a winner, you have to make sure it looks like one. That old proverb, "Don't judge a book by its cover" doesn't apply to screenplays. Remember, this is Hollywood. Looks count. Don't give them a reason to dump your script in the trash before even turning to the first page.

So, first, let's get physical:

- Use the correct format. There's screenwriting software that translates your text into the industry-standard format. If you're serious about screenwriting, you should spring for the software.

- Check for typos and spelling/grammatical errors. Sloppy script = sloppy story. Don't be sloppy in any aspect of this process.

- Keep your script between 90 and 120 pages. Don't cheat with the "tightening" features on your software. People in the industry have a built-in detector for that.

- Use a title page that states the title, your name, and your contact information. Period. Don't include any mention of your script being legally protected. This comes off as amateurish.

- Use three-hole-punch paper, bound with two 1¼ -inch brass fasteners, leaving the middle hole open. Use only solid brass fasteners, not the flimsy ones. (Most professionals use Acco Brass Fasteners #5R.)

- Print your script on a good printer.

- Don't include pictures or photos or illustrations of any kind.

- Use a plain card-stock cover (available at any office supply store). Any color is fine, but don't choose glossy or fluorescent. And do not adorn your cover with any kind of info or decoration.

Follow each of these rules to the letter. Any deviation will brand you as unprofessional.

Next, your script needs legal protection; otherwise, you may worry about someone coming along with a wodget that looks just like your widget. While the chances of this happening are fairly small, it's best to err on the side of caution.

One way to cover yourself is to register your script with the Writers Guild of America (WGA)—www.wga.org. For a modest price, your script is protected for ten years. Another option is to copyright your script through the U.S. Copyright Office. Go to www.copyright.gov and click on PERFORMING ARTS, as you're protecting a piece of dramatic work. For a fee, your script is protected until you die, plus an additional seventy years after your death. Most screenwriters only register their script with the WGA, as the paperwork is processed more quickly. However, a copyright is more binding in court and lasts much longer. You may want to do both.

With your script ready to go, set it aside. Now, you've got to pitch it.

The Pitch

Wait a second, you're thinking. You just told me I couldn't pitch these people an idea by itself. So I went off and wrote a whole script. Can't I go ahead now and mail it off to an agent? A producer? A star who's perfect for the leading role? I'll even enclose a little cast list of whom I think would be right for each part and we'll discuss it in the limo ride from LAX.

Sorry, it just doesn't work that way. People in the industry have enough solicited material to wade through on any given day without troubling themselves with an unsolicited script unless they have some inkling that it has promise. And that's exactly the purpose of the pitch. To give them that inkling, that promise.

And then they'll want to read your script.

What's the key to a killer pitch? Think of the whisper game. You tell someone a story; that person turns to then neighbor and repeats it; the neighbor turns to someone else and repeats it and so on. Ideally your pitch will undergo an industry version of the whisper game. An assistant tells your pitch to the agent who tells it to a producer who tells it to a studio executive who tells it to the studio head. In order for the pitch to be great, capable of reaching the most important ears in the industry, it must be clear, concise and, above all, intriguing.

You'll actually need to create three different versions of your pitch—a logline, a one-paragraph pitch, and a brief synopsis. Somewhere along the way, each of these three versions comes into play. Crafting the perfect pitch is a lot of work, but you need to take the time and effort to get good at this. So much in the movie business revolves around pitching.

The Logline

A logline is a one- or two-sentence encapsulation of your story. The story in a nutshell. It's basically the same thing as a premise, but while a premise conveys the story idea in a few sentences, a logline conveys it in only one or two. With the logline, pay close attention to the wording, making the summary as compact and compelling as possible.

For example, the premise of Die Hard would go something like:

A New York cop visits L.A. for the Christmas holiday to patch things up with his estranged wife. A party in the corporate tower where his wife works is interrupted by high-tech terrorists who take everyone hostage in a ruthless scheme to crack the company's vault. The cop is the only one who has a shot at stopping them.

A logline of Die Hard would look more like this:

A New York cop visiting L.A. is the only one who can stop the terrorists who have invaded a high-rise and taken the people inside hostage—including the cop's wife.

The logline is the quickest kind of pitch, which makes it extremely valuable in the movie business, where everyone is always pressed for time. A story is often pitched for the first time as a logline—over the phone, on Web sites, poolside at a party. Think of it as a literal pitch, a fastball into the strike zone. (Be careful not to confuse a logline with a "one-sheet." A one-sheet is the sexy ad slogan used on the movie's poster and promotional materials. For Die Hard, it was: "40 stories of sheer adventure!" While a one-sheet may titillate, it doesn't tell us much about the story.)

The logline usually contains the following:

- A glimpse of the protagonist

- The basic story idea, usually including the goal and major obstacle

- A sense of the genre

You also want the logline to have some kind of "hook" to it, something that grabs attention because it's so fresh or surprising or provocative or dramatic. In the Die Hard logline, for example, the hook has three prongs: It's not enough that the off-duty cop has to battle terrorists. Hell, that's ho-hum. In this story he has to do it alone. And not only that, he has to do it in an L.A. high-rise. But wait, there's more. There are hostages to be rescued—among them his wife!

Here are loglines that would work for our other four movies:

Tootsie

A struggling actor becomes a soap opera star by disguising himself as a woman, only to fall in love with the leading lady.

Thelma & Louise

Two southern women—a no-nonsense waitress and a sheltered housewife—turn into outlaws when a weekend away spins out of control. Running for their lives, they find their souls.

The Shawshank Redemption

A mild-mannered banker must find an endless reserve of strength while serving a life sentence for murder inside the menacing Shawshank Prison.

Sideways

An insecure novelist and his womanizing friend learn hard lessons about love, cheating, and Pinot Noir through a series of misadventures on a weeklong road trip through the California wine country.

High-concept stories like Die Hard, Tootsie, and Thelma & Louise can usually be nailed in just one or two sentences. The idea alone is a grabber. Low-concept ideas like The Shawshank Redemption and Sideways are more challenging to pin down in a logline because the focus is more on character. While these kinds of stories aren't expected to have as much flash, you still want to make them sound as intriguing as possible.

The One-Paragraph Pitch

The one-paragraph pitch stretches the logline to include a few more details about the protagonist and story. Like the logline, the one-paragraph pitch should be carefully crafted so that you build excitement in very concise language. Try to keep it under 125 words.

The one-paragraph pitch for Die Hard might go something like this:

John McClane, a wisecracking New York City cop, comes to L.A. to save his failing marriage. Yet everything comes to a crashing halt when a band of terrorists invade a high-rise office building and take the people inside hostage—including McClane's wife. The terrorists seal off the building electronically and keep the authorities at bay with missiles. Once they crack a computerized code protecting millions in bonds, they plan to blow the building, killing the hostages and masking their escape. McClane, lurking in the building, unseen and armed with just his wits, is the only one who can stop them.

The Synopsis

The synopsis is the longest version of your pitch. You're laying out the major plot points here, giving a fuller sense of how the movie will unfold. The synopsis, however, should run no longer than 500 words (one single-spaced page).

To see a synopsis of Die Hard, go to www.WritingMovies.info.

Take a Shot

Pick a favorite movie. Pretend you wrote the screenplay and are now trying to sell it. Write a logline for the movie, using only one or two sentences. Make it as concise and compelling as possible. (You can test yourself against our answers by using one of the movies listed at www.WritingMovies.info.)

The Players

Now that you have your script and pitches ready to go, let's briefly meet the various people you'll want to get to, those already mingling and mixing beyond the velvet rope. The players.

The Movie Makers

Ruling over the kingdom are the studios—behemoth companies that oversee every aspect of a movie's production, including development, financing, marketing, and distribution. At present, there are six: Warner Bros., Fox, Disney, Sony, Paramount, and Universal. All six are based in or just outside of L.A. and each has a multitude of projects continually in development. Studios tend to favor the big-budget Hollywood-type movie, though most of them have smaller offshoot companies, such as Universal's Focus or Fox's Searchlight, that make indie-style movies. Then there are big production companies, often called the "mini-majors," that do all of this on a slightly reduced scale.

The top decision-makers in these companies are the executives, or "the suits." They go by all kinds of titles (usually prefaced by "vice president") and they are the ones who decide where the money goes and what projects are granted the power of a "green light."

Then there are the hundreds of smaller independent production companies known as "indies." There are actually two distinct kinds of indies: those that make primarily Hollywood-style films that are financed by the studios (many have their offices right on the lot). And then there are the truly indie indies that make films without any outside interference. They lean toward lower budgets and the offbeat style that's become the trademark of the indie film. These companies too, however, often turn to the studios for help with financing, marketing, and distribution. That's why when you watch the opening credits of a movie, you often see the banner of a production company (sometimes several) in addition to the studio banner. While many indies are in the L.A. area, they're also based in places like New York, San Francisco, Chicago, and Miami.

Producers run these production companies. They oversee all the various elements of a movie's production, from financing to casting to arranging that the crew has enough to eat. There are no set requirements to be a producer. While one producer might have a shelf full of Oscars and a parking space on the studio lot, another producer may be running his fledgling outfit out of his basement. All it really takes to call yourself a producer is a phone and some stationary with a letterhead.

Studios and most of the larger production companies have development departments. The heads of development determine the potential of incoming scripts and actively pursue other, adaptable material such as novels, plays, comic books, and magazine stories. You don't hear much about the development people, but they are a significant part of the process, especially where the writer is concerned.

Only the smallest and newest production companies will consider material from someone unknown to them. If you're a newcomer, you won't convince the studios or most production companies to look at your script. They won't even look at your pitch. They don't have time to sift through this material and they are paranoid about being sued should they produce something similar to your project. You will need help getting your material before their eyes.

The Talent

Talent refers to the actors and directors. They're the most famous players, certainly the most visible. Should one of them, especially one with any box office clout or star caché, take an interest in your script, the chances of it selling go way up. You may have someone in mind who would be "perfect" for your project and feel you absolutely have to get your script to that person. But talent is no more likely to consider your material than the studios, for pretty much the same reasons. And, look, if talent were open to considering anyone's script, writers would simply hand them their scripts as they stepped out of their limos and Hummers. "My number's on the cover. It's got Oscar written all over it." Ain't gonna happen. Actors and directors safeguard themselves from such intrusions.

Of course, there are exceptions to the rule. A first-time writer-director, Dylan Kidd, hit the jackpot when he approached the actor Campbell Scott in a Manhattan café and asked if he would read his script Rodger Dodger (which he carried around with him at all times). Scott accepted the script, liked it, and got it made into a movie starring himself. Bear in mind, however, that Scott is a minor star, who also produces low-budget films. Approaching A-list talent, on the other hand, will most likely lead to an unfavorable result, especially when there are bodyguards present. Once again, you'll need some help getting your material past the bouncer and into the club. You'll need some representation.

The Reps

Representation is invaluable. The reps introduce writers and their material to the moviemakers (and sometimes to the talent). More than anyone else in the industry, they're the ones who can get your name on the list. A great rep will even personally usher you past the bouncer and straight into the club. Through phone calls, lunches, and parties, the reps stay on top of what producers are looking for and attempt to get you work on rewrites whenever they see a good fit. Having a rep gives you instant credibility and connections. While obtaining one isn't the easiest thing, it's an almost essential step for the writer trying to break in.

A writer can be represented by an agent, a manager, an entertainment lawyer—or by all three at the same time.

First, agents. To take on a new client, an agent must truly like the writer's work and/or believe the work is marketable. Naturally, agents prefer to represent clients who generate saleable scripts on a semiregular basis rather than one-script wonders. Should a studio or production company show interest in a client's script, the agent will negotiate the best possible deal for the client, and if more than one company should want the script, the agent will put the script up for "auction" (a writer's dream) and let the companies bid against each other, driving up the price. For negotiating the deal, refining the terms of the contract, giving advice on scripts, agents do not directly charge the client. Instead, they take 10 percent of everything the writer makes from the material represented by the agent.

Agencies come in three sizes: big, medium, and small. The so-called Big Five—CAA, ICM, UTA, William Morris, and Endeavor—are also the most powerful, devoting their services largely to heavyweight writers and talent. The medium-size agencies usually have four to ten in-house agents, while the small agencies have only a few agents, sometimes only one. In the medium and large agencies, you will find a hierarchy of agents. Sometimes the levels are designated by the terms "senior agents" and "junior agents." As you might expect, the senior agents have much more experience and clout than their lower-level counterparts.

Managers are similar to agents but they are not regulated by the Writers' Guild of America, as agents are. In fact, managers are not regulated by anyone. This means that they cannot finalize contracts (an entertainment lawyer or agent would have to do this). Like agents, managers take their pay out of the client's gross, but there is not a set percentage. They usually charge from 5 to 15 percent.

As managers tend to have fewer clients, they can offer the writer more time and attention than an agent can. For example, while an agent may not call a writer for weeks on end, a good manager will stay in regular touch with a client, providing in-depth notes on a script and/or just offering encouragement. There are many managers who function almost as partners and will participate in their clients' projects as a producer. Some managers work with well-established companies, or with a stable of colleagues, while others operate entirely on their own, often working out of their home or rented office space.

Some writers have both an agent and a manager. This may seem extreme as it requires paying off a lot of money in percentages, but given the highly competitive nature of the business, even for those already inside the club, some writers figure they can use all the help they can get.

There are also entertainment lawyers. Like agents and managers, the better entertainment lawyers in L.A. are very plugged into the movie scene. They can get scripts read by key people and finesse the finer points of a contract. For these reasons, many screenwriters work with a lawyer in addition to an agent and/or manager. An entertainment lawyer usually takes 5 percent of any sale made through his assistance.

Last, there are the swindlers. When anyone in the business, be it ABC Agency or XYZ Management Firm, asks you for money, he might as well have "swindler" scrolling like a Times Square ticker across his forehead. The most common con is their request that you pay a "reading fee" to make a critical assessment of your script. This practice is shady. Legitimate agents and managers make money only when you make money. If an agent or manager asks you for money, stay away. They make their money from these bogus fees, not by selling scripts.

Targeting

If you have a script, you need a rep. But with thousands of reps out there, not to mention the different kinds—agents, managers, entertainment lawyers—which one should you go after? Who will best serve your needs as a screenwriter? It's a hard thing to determine and often it's hit-or-miss. Sometimes you just have to go with your gut. But the bottom line is that any representation is better than no representation. Now it's time to do a little homework. You'll need to find the most current and correct information to enable you to create a list of viable reps whom you can contact.

First, you'll need specific names. Never cold-call an agency to say, "Hey, I've just written a blockbuster and am looking for a good agent to rep me. Any ideas?" You'll be summarily dismissed. You need to target specific reps.

The most reliable resource for contact information is the Hollywood Creative Directory, AKA the HCD, AKA the phone book of the entertainment industry. There are actually several volumes of the HCD that deal with different aspects of the business. The volume most helpful to you as a screenwriter is the Hollywood Representation Directory, or HRD, which lists thousands of literary agents, managers, and entertainment lawyers, under the names of their respective companies or agencies. (The volume called Hollywood Creative Directory lists studios and production companies.) The HRD comes out twice a year, as the players tend to move around a lot. Be sure to consult the most current edition so that you're using the most up-to-date info. Unfortunately, this directory isn't cheap; you might want to track one down in a bookstore, where you can browse through it for free. You can also subscribe to the HCD Web site, where you receive a continually updated version of the HRD, in addition to some other directories. The subscription for this is on the steep side, too, but if you drank one less mocha latte per day, you could probably afford it.

Because you're starting out, don't think you have to target only the smaller agencies or management firms. Query every kind—small, medium, and large. The biggies will be less likely to consider you, but the more reps you query, the more chances for a positive response. No pain, no representation. In the end, the best agent/manager is the one who believes in your talent and works hard to get your material out there.

There are also numerous other resources to aid you in your targeting research. On the Internet you'll find dozens of Web sites devoted to screenwriting and the movie business. There are two trade papers for the entertainment industry, Daily Variety and the Hollywood Reporter. Again, no need to buy them; just flip through them at a large newsstand or bookstore. Inside their pages you'll read about films in production, script sales, company shake-ups, "anklings" (resignations), agent hirings, and promotions.

Zeroing In

Now it's time to narrow down your list of reps to those that might make a little more sense to contact than others. Some ideas:

1. Connections. As in most careers, if you know someone who knows someone who knows someone, you'll have a "friendly" target on the inside. It behooves you to take advantage of the fewer degrees of separation—whether it's a relative, friend of a sister-in-law, an old classmate. Any connection you have is the obvious and best place to start.

2. If the shoe fits. If you have no connections, the best approach is to pinpoint agents and managers who represent material that seems to be in the same vein as your own. Think of recent movies, especially successful ones, that have a style and sensibility similar to your script. Find out who the writer is and who reps them by calling the Agency department of the WGA, or by searching their Web site. Also, check out the script-sale news in the trade journals or movie-business Web sites. If the script seems to fall within the same ballpark as yours—zany teen comedy, slasher, biopic, psychological thriller—note the agent and agency that made the sale.

3. Ear to the ground. While you're trawling the trades and Web sites, take special note of the insider news. For example, you might come across a small item about an agent who's broken away from Agency M to start up his own agency. Given that he's breaking new ground, he just might be open to taking on new clients. Or you may read that a producer is looking to do a movie about Exactly What You've Written. Get his name and info from the HCD.

Other factors to consider as you zero in:

Los Angeles: You want an agent or manager who is located in the greater L.A. area. Only the ones who drive on the 405 are truly plugged into the movie scene. (Granted, there are several exceptions among New York agents and managers.)

WGA signatory: For agents, you need one who is a signatory of the WGA. Only these agents have the legal right to negotiate contracts with studios and production companies that are also WGA signatories (all the significant ones are). WGA affiliation does not apply to managers.

Literary, Film: Make sure you're tracking "literary" agents, who rep writers, as opposed to "talent" agents, who rep directors, actors, or other performers. And you'll find some names that specialize in either film or TV.

Do what you have to do: In these directories or elsewhere, you'll often come across stipulations such as "no unsolicited submissions" or "by referral only." Truth is, most of the significant companies and agencies post these barriers. You can heed these warnings and move on to the next listing, or, if it's someone you feel strongly that you should contact—say, an agent who sells your kind of comedy—then by all means ignore the warning and make the attempt. No industry police will come knocking on your door to confiscate your screenwriting software.

Finally, keep in mind that the same strategy you've employed to target reps can also be applied to targeting smaller production companies. If you're having no luck securing a rep, it's worth a try.

All in all, how many reps should you target? Obviously you can't contact everyone, nor should you. But obviously, the more pitches you make, the more chances you'll get. Shoot for a hundred reps as your max, but send out your letters and make your phone calls in waves of twenty-five. That is, do the first wave, wait a month or two, then do the next wave of twenty-five. It will make the process saner and much more manageable. Start with your top choices, those that seem like the best fit. As you do this, be sure to keep careful track of the process: Record all the reps that you contact, the date you contact them, the response (if any) that you receive. This is your business now. You have to stay on top of it.

Making Contact

As you now know, you can't just send your screenplay to those reps you've targeted. It's not how it's done. First you'll need to contact them and ask if they would be willing to look at your screenplay. Your pitch is what will entice them. And once enticed, they'll want to take a look at the script.

Should you send a query letter or simply call them on the phone? Opinions vary on this. Some argue that no one in the industry bothers with letters anymore; it's all done on the phone. Others believe that making a cold call is bad form; you're just going to tie up phone lines and make people resentful.

So try both ways. And if a phone call fails, write a letter. If a letter fails, call.

Let's take a look at each approach.

The Phone Call

The phone call is more direct and aggressive than the letter, and that's not necessarily a bad thing. So learn to get your phone game on. Sound smart, professional, and confident without ever being rude or pushy.

The call will probably go something like this:

1. You call the person you've targeted from your research. Ask the "gatekeeper"—a receptionist or assistant—to speak to that person.

2. The assistant will toe the agency line and tell you something like, "We don't consider unrepresented material."

At this point, you can either:

3a. Thank them anyway, hang up, and move on to the next target.

Or:

3b. Try to edge past the agency's protocol by mentioning that you've written a comedy (or whatever your genre) that you believe Agent Q could really get behind. Then, if you don't get an immediate protest, go right into your logline. If they seem a tad interested, you might even go into a verbal version of your one-paragraph pitch. Why not? These people often have the ear of their superiors. At this point, the person on the line will either be impressed by your pitch and request the script, or they'll simply repeat the "no unrepresented material" line. If that's the case, don't bother leaving a message with them. It won't be returned. Just remain gracious and say thanks anyway.

Regardless of what happens, always treat the person who answers the phone with courtesy and respect. Don't view them as obstacles, but as potential allies. You need them. If they hear a smart, winning personality on the other end of the line, they will be much more inclined to hear your pitch and relay your script to their boss. If you're pushy or demanding, you've pretty much wasted an opportunity. Also, you never know where these people might end up; invariably they are grooming to be players themselves.

Whenever the phone route fails, write the target rep a query letter. This is the game. You have nothing to lose. No pain, no representation.

The Query Letter

If you're nervous or uncomfortable pitching on the phone, the better way to go is to write a query letter. While some industry insiders consider it a waste of time and postage—many query letters do get tossed out with the junk mail—there are some letters that get noticed.

A winning query letter will be brief, but impressive. A half page is ideal, never more than one page. Use decent paper and proper business format. These should never be handwritten. Always address a specific person. If you find yourself writing "Dear William Morris Agent" or "To Whom It May Concern," you might as well be writing "Dear Dumpster."

There is no standard template for a query but it usually consists of these parts:

Reason for contact: State the reason you are contacting this specific person. If you have any connection to this person, say so up front. If not, say something else, such as mentioning you're aware that he or she represents a writer you admire and feel a kinship with.

Pitch: Pitch your story, using the one-paragraph version. This, of course, is the part that really counts. Don't brag about how good your script is. Show them by giving a killer pitch.

Who you are: Say a few words about yourself, especially as a way of demonstrating your ability to have written a great script. If you're a graduate of a screenwriting/playwriting/ creative writing program, or if you have something published or produced, include that here. This shows that writing isn't just a hobby you've been tinkering with down in your basement. Also, any personal experience that relates to your story might be worth mentioning.

And then sign off by saying you hope they'll request the script.

Here's pretty good example of a query letter:

Samantha Waters

The SWE Agency

1234 Rodeo Drive

Hollywood, CA 90210

Dear Ms. Waters:

I'm aware that you currently represent Meredith Harmon, who wrote The Middle Man. I'm a huge fan of that film, one of the most original comedies to come along in quite some time. I've written something with a unique edge of its own—a dark romantic comedy called Noir.

Noir is the story of Frank Merchant, a hard-boiled detective who—after chasing a suspected serial killer down an abandoned subway tunnel—enters this world, the real world, where he discovers that he's just a character in a crime novel series. When he learns that his maker, the author, plans to kill him off in the series' final installment, Frank must convince Maggie Turnbull, his biggest fan, to talk the author out of it and thus save Frank's "life."

While I was a creative writing major at Oberlin College, I always ended up steering my short stories into screenplays. Finally I just gave in to my cinematic desires. After completing Noir, my third feature-length screenplay, I feel both ready and confident to be seeking representation at this time.

Thanks for your time, and may I possibly send you my screenplay?

Sincerely,

Michael Cortez

Take the time to write an excellent letter. Any information that you can learn about your target rep (i.e., news items from the trades, an interview in a magazine) will be useful to add a customized touch and make your query stand out from the scores of others these folks receive. Don't get too cute or flashy. Just be yourself, on a good day. You want to come off as smart, likable, and professional. Be extra attentive to your spelling and grammar.

Finally, be sure to include an SASE (self-addressed stamped envelope) or it's highly unlikely you'll get a response. Send your query by regular mail, via the U.S. Postal Service. No need to use FedEx. Avoid faxing your letter, unless someone has specifically requested that you do so.

Sad to say, but most of the people you send query letters to will not respond. That's just the way it is. The rules of courtesy as we know them do not apply in the movie business. Silence usually means "no," and it's nothing personal. But if you have a killer pitch and you send it to enough of the right people, someone will eventually request your script.

And then there's e-mail. This is the twenty-first century after all, and more and more places are accepting it. But send your letter as an e-mail only if you know for sure that you're welcome to do so, and this will require having the e-mail address of the specific person you've targeted. When sending an e-mail query, you should observe the same professional care as you would with a conventional letter. Don't start sentences with lower-case letters, and by all means no :). As for the subject heading of your message, be simple and clear, like so: Query letter—Noir.

Getting Read

If it all goes well, the target person may ask for the script, the synopsis, or both. The person will send you a standard release form and you'll sign it, waiving your rights to sue should they represent or produce a movie that bears any resemblance, striking or otherwise, to your story. (Remember, they're all paranoid about getting sued.) You'll sign the release because, at the end of the day, what's the alternative? You send your script to no one. Just take a deep breath and have a little faith. Almost never do true professionals steal ideas. If they do, and your script is protected, you still have some legal recourse.

Send the script right away before you are forgotten. Enclose with it a brief letter, reminding them that they requested the script and refreshing their memory with the logline. Use Priority Mail through the U.S. Postal Service this time, and be sure to write in bold print AS REQUESTED on the envelope to prevent it from getting tossed in the slush pile, which is what happens to unrequested material. Send it via FedEx or e-mail only if they've specifically requested it to be sent as such.

So, now they finally read it, right? Right. . . ? Well, not exactly. Virtually all players—agents, managers, producers, studio execs, development people—rely on "readers" to give scripts a first screening. The larger outfits keep a stable of readers on staff, while the smaller ones commonly use interns, freelancers, or office assistants. Despite their low place on the totem pole, readers wield considerable power as far as you are concerned. They are the ones who decide if your script moves forward or stops at their desk.

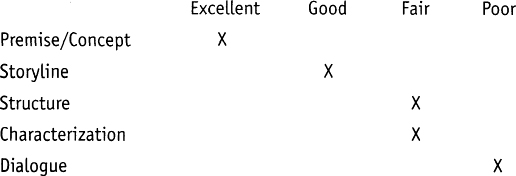

After readers read your script, they write an assessment report, known as "coverage." Coverage comprises a synopsis and a one- or two-page critique of the script's merits and flaws. There will also be a kind of scorecard that looks something like this:

Finally, and most significantly, the reader renders a verdict of "Pass," "Consider," or "Recommend." This verdict carries a lot of weight. When a player reviews coverage, their eyes will naturally go straight to the verdict. If, like most scripts, yours receives a "Pass," it's pretty much game-over, with this particular outfit anyway. Should a script earn a "Consider," then the odds are good that a superior will at least give it a look. Should a script merit a "Recommend," then it is almost certain to be read by the higher-ups. Readers rarely "Recommend" anything, however; if their boss reads the script and disagrees, the reader's judgment will henceforth be questioned. So even if the readers love your script, chances are they will play it safe and give it a "Consider."

The Sale or Option

Let's say your script has passed the first test. The reader gave it enough kudos to make an agent or manager want to rep you, meaning he or she will send your script around town to those producers and studio executives he feels would make for a good fit. These producers and executives, in turn, will give the script to their own readers for a second opinion. The process never ends. But the good news is, your name is getting out there. Your script is being talked about by industry people.

And then, let's say, in the best of all possible worlds, your script has impressed other readers and maybe a few suits along the way. There's been talk of actors who would be perfect for the lead. The heat and buzz intensify. A production company or studio is interested. Very interested. Your phone will ring. They want your script. What will they do to get it?

The interested party will do one of two things:

1. They will buy it.

Woo-hoo! This is what you've been waiting for. This is why you've holed up in your apartment and ignored your friends and

family over these past months. The payday can be phenomenal, depending on how much a studio or producer wants it (or how badly

they want to bury it). The amount can be anywhere from $100,000 to more than a million. At the least, if you're dealing with

a company that is a signatory of the WGA, there is a minimum they are required to pay you for a spec sale, which, at this

writing, is in the mid-five figures. With a non-signatory company (usually a smaller production company), the money can be

much lower.

Or . . .

2. They will option it.

An option is not the same as a sale. Think of it more as a rental. An option means they are purchasing the right for sole

and exclusive access to your script for a set amount of time, usually six to eighteen months. When the option expires, the

producer or studio will either renew the option for another six to eighteen months, or the script goes back to you. If and

when shooting starts, known as "commencement of principal photography," an option turns into a sale and the purchase price

goes into effect.

As a rule of thumb, a standard option with a studio or larger production company is 10 percent of the purchase price, which is how much they'll pay to buy your script should they decide to move forward and make a movie from it. So the terms of an option agreement might be $10,000 against a purchase price of $100,000. But if you're dealing with a small production company, they might pay you considerably less, or nothing more than a contract that promises monetary compensation only if the project goes into production.

An option, while not an outright sale, is still good news. It's a major vote of confidence to have a producer or studio interested in your script. Your name still gets out there and if you're lucky, you may get a little money to boot.

Development Hell

After your screenplay is sold or optioned, it goes into development. Rarely, if ever, does a writer's original script experience an immaculate conception—getting shot as is. Many of the players involved feel compelled to throw in their creative two cents on the script (usually worth much less than that) before any production checks are written. Except in the case of some low-budget indies, scripts are "developed," or reworked further. They are often developed to death. So much so that the process of developing a script is often known as "development hell." If you're lucky, you will be kept on to do at least the first couple of rewrites, per notes from one or more of the studio executives and/or the producer attached to the project. If you're not so lucky, your script will be given to someone else to rewrite. It's not unusual for a script to be worked on by numerous writers.

Here's a fairly typical example. My writing partner, Gary Nadeau, and I wrote a spec script called Godspeed, Lawrence Mann, about a thirtysomething Mercury astronaut who returns to Earth after being lost in space for forty years. MGM optioned it and, about a week later, our agent at William Morris revealed that Michael Douglas was interested in playing the lead role. Our reaction was less than ecstatic as Douglas at the time was about twenty years too old for the role. All the same, Douglas was an A-list actor with Oscars for both acting and producing. Who the hell were we to snub Michael Douglas?

So, in our first rewrite, my partner and I had to make adjustments to accommodate the character's older age but, hey, we had Douglas attached and we were now part of what appeared to be a go project. Until, that is, we were taken off the project in favor of an A-list writer. When that writer turned in a disappointing rewrite, we were brought back on and wrote umpteen more drafts, only to be replaced yet again by another A-list writer, who turned in another disappointing rewrite. Eventually the project ran out of steam because the producers could not agree on the direction the script should take.

The script currently resides in development "limbo"—floating out there in space like our hero—although one of the two producers (the other being Douglas) has recently taken sole control of it and intends to get it back up and running.

That's development.

The Professional Screenwriter

Most working screenwriters don't make a living by selling their own scripts. Most working screenwriters make their living by rewriting other writers' scripts. Or by writing scripts based on ideas or properties (books, comic books, articles, plays) owned or generated by executives and producers. It's "work for hire," but it can be very lucrative. The two A-list writers who did rewrites on Godspeed, Lawrence Mann, for example, made ten times more than we were paid for all of our writing services on the script that got everyone interested in the first place. You would think that the creator of the original story would be the one rewarded most. Unfortunately it rarely works that way, at least not in this particular club. (And, in yet another aspect of the Hollywood madness, many incredibly successful screenwriters have never had their original material produced.)

To get these rewrite jobs, you have to go up for them, much like an actor must audition for a part. Your agent and/or manager will have the most current listing of "open" writing assignments, which could be either a rewrite or developing a concept from the ground up. Ideally you'll zero in on two or three of these projects, the ones that speak not only to your personal taste but also to your strengths as a screenwriter. Your rep will set things up. Then you'll carefully craft a pitch for each one—your take on the project, how you would rewrite/develop the script/idea. You'll deliver each pitch either as a 20-minute in-person presentation or as a 10-to 15-page treatment (a prose version of the story), or both.

If you're able to consistently deliver on these jobs, work will come your way on a regular basis. In addition, you'll get the chance to pitch your own ideas—without necessarily having written the scripts—and possibly get offered a contract based solely on that pitch. Pitching your own ideas, as well as your takes on rewrites, is akin to doing stand-up. There's no question it can be nerve-racking. Before the meeting, you sit outside the office, like a comic waiting in the green room to go on. You sip on the Evian or coffee the assistant offers, as you flip through the day's trade journals on the glass coffee table. And then the door opens, the producer or studio executive appears and lets you in. Showtime.

By the time you reach this point, you have essentially established yourself as a damn good screenwriter. The players in the industry will not only know your name, they'll put your name on the list. By now, you have not only made it past the velvet rope, you've made it onto the dance floor.

The Velvet Rope-a-Dope

Let's not lose sight of the facts: Every year about 80,000 new specs try to enter the market, or the "Big Lottery," as some writers call it. Every year about a thousand scripts are bought or commissioned, but only fewer than 10 percent of those sales are specs, meaning less than a hundred specs are purchased per year. These are very rough (and unreliable) stats, but you get the idea. The odds just aren't good for selling a spec script. The odds go up a smidge for an option but not much. You might actually be better off if you write your story as a novel, publish it, then try to sell the film rights. But that can be a tough route, too.

With the odds stacked so high against you, what can you do to beat them? Here are a few suggestions and strategies.

Write a fantastic script

I know, I know. Easier said than done. It's like saying, to win the game you have to go up to the plate and hit a grand slam. But truth is, if you don't swing for the fences, your script will not make the necessary impact. It will be just one of the countless decent scripts that flood the offices of producers and studio execs every day and ultimately slip into oblivion. But write a fantastic script and people in the industry will sit up and take notice. Even if they're unable, for whatever reason, to buy or produce or represent your script, they won't forget you. They may ask what other projects you have in the works, or they may offer you the chance to come up with a take on an in-house project they're looking to develop or rewrite. A fantastic script is the best possible calling card. If you have more than one, even better.

The fact is, breaking in is more about marketing yourself as a writer than about marketing any one script. That's why it's so crucial that you write scripts you feel passionately about, rather than to merely write what you think is saleable. Passion will bring out your best talent as a writer and storyteller and that talent will become the real ticket that gets you in the door.

Connections

While it's true that a great script will sometimes speak for itself, even the masterpieces, more often than not, need help from the inside. Without it, getting your script into the right hands, while not impossible, is a tricky proposition that requires luck and pluck.

It's extremely helpful to have an "in." A viable connection. Ideally, you have a friend in the business. Or you know someone who knows someone. But, hell, you've been holed up in the back booth of the Night Owl Café in Toledo writing your damn script for the past year and a half. When have you had time to hobnob with anyone but Dolores, the waitress? Who you gonna meet in Toledo?

Consider everyone you know and have ever met in your lifetime. And everyone means everyone. What about that guy who used to live down the hall from you your freshman year in college? You used to cram for biology exams together. Didn't you recently read in the alumni magazine that he's working now as junior agent in L.A.? Or even Dolores, the waitress. Didn't she mention that her younger brother's married to a woman who works for a producer in New York?

If you don't have any connections, what then? Make some. It's not that hard. Especially if you have a great script to show.

To live and write in L.A.

If you're truly committed to breaking into this business, you should consider moving to L.A. Simply put, it's where the action is—the studios, the major production companies, the players, the deals. You might bump into a producer at the gym, for example, and be able to pitch her your killer logline while sweating side by side on the treadmill. A friend of mine met his ICM agent in an L.A. pool hall.

That said, L.A. can also put a crimp in your creativity, if not your soul. You're sitting in a café in West Hollywood. Three guys in the back are clacking away on their laptops, writing screenplays. The woman sitting next to you is on her cell complaining to her agent about the studio script notes she just received, and the pair next to you are actually having a creative meeting. L.A. can be angst inducing as the industry chatter buzzes around you like flies. You start to fret about your own project, or wonder why your agent hasn't called you back. Writing takes a back seat to worrying.

A compromise is to simply hang out in L.A. for a few weeks every year, especially if you have a great script to unleash. If you've managed to make favorable contact with some people out there, you might be able to set up meetings. That's the way I've done it thus far. But then I live in New York, which is the second best place to be.

Get a job in the biz

There's no better way to meet players than to work in their offices. Get a low-level job working for an agent or producer, perhaps even working as an intern. You'll see firsthand how things operate and you'll find a chance to slip someone your work. My first break in this business came when I interned for a producer while I was still a student at NYU. I would give him scripts of mine to read on the plane to L.A. He wound up optioning one of them. Of course, most of these jobs are in L.A. or New York.

Attend film festivals

They're everywhere these days, from Seattle to Sydney. Hell, by now Toledo might even have one. While some of the larger film festivals preview films that are soon to be released, most festivals showcase indie movies that are still looking for a distributor. Movie biz folk are usually in attendance and this is a good place to hobnob with them—at the theaters, bars, after-parties, restrooms.

Take writing classes

There are many good screenwriting classes that can help you fine-tune your screenwriting craft. In addition, you'll get feedback and support from your teacher and classmates, not to mention the structure and deadlines that many of us need to stay disciplined. You're also getting to know others interested in screenwriting with whom you can share information, which counts as a kind of networking. If it's within the realm of possibility, consider entering a graduate program at a reputable film school. The best of these—UCLA, USC, AFI, NYU, and Columbia—can be especially helpful to emerging writers. Also know that there are many script consultants available for private consultation on scripts, some working independently, others with teaching organizations. Classes and consultations cost money, of course, so make sure you're handing it over to a reliable place.

Join a writing group

A writing group is simply a group of writers meeting on a regular basis, reading and critiquing each other's work. Like a writing class, they can provide support, camaraderie, and those deadlines that don't let you slack off. Join a group or form one of your own, but make sure that all participants are responsible and serious about their work. This isn't like a knitting club; it's your career. If everyone stays on task, good work—and sometimes good networking—can come out of it.

Enter screenwriting contests

There are well over a hundred screenwriting contests out there, offering prizes that may include free script software, meetings with agencies for possible representation, or a nice chunk of change. You should be aware there is a ladder of prestige among contests, ranging from the elite to those no one in the business has ever heard of. Each one requires an entry fee, so choose your contests carefully or you'll blow a fortune.

Can taking a top prize in a contest get you noticed by people who count? For most of them, probably not. But there are a few top-tier contests that the players keep an eye on, requesting scripts from those who place very high. Conduct research to find which contests truly count.

Try online script marketing

Dozens of Web sites offer to post screenplays on their sites and market them to a subscriber base of film industry professionals, including agents, managers, producers, and executives. It's basically an online version of the open-air bazaar where pros trawl for product they can develop. Different sites work in different ways. For example, at some sites the pros surf the loglines, selecting those scripts they will go on to actually read. Other sites provide coverage of your script, passing along the ones marked "Recommend" to the participating pros.

Do people actually break in this way? The online brokers all boast success stories, and they claim that their service will revolutionize the spec market, becoming the primary way entertainment professionals look for fresh writers and stories. This may or may not be true. Some people, however, have managed to hook up through these sites.

There is also an in-person method of pitching for a fee, known as the pitch-fest. A group of industry types gather in a conventionlike atmosphere and listen to verbal pitches from the participants. Between the two, you are probably less likely to see significant players at a pitch-fest than on the better online marketing sites.

All of these places charge a fee, of course, so check out any outfit you're considering. Look for the ones that seem the most reputable.

Produce something yourself

If you've written something that can be made on a low budget, you just might want to produce it yourself, perhaps shooting digitally, which is much cheaper than filmstock. An even more realistic option is to write and produce a short film, which you can then show as a sample of your work. It's easier to get folks in the business to watch a short film than read a long screenplay. If you're not a director, go to a film festival and find one.

You Are the Protagonist

You, as a screenwriter, are the protagonist in your own story. You weren't satisfied with your ordinary world of corralling runaway shopping carts in the A&P parking lot or fetching romance novels for the purple-haired ladies at the local library. You were reluctant, at first, to pull yourself out of that safe and familiar setting, but you finally listened to the voice inside your head (or maybe gut) and answered the call to be a screenwriter.

In the tradition of all heroes, you'll encounter obstacles on the path to your first break. Plenty of them. A demanding full-time job that leaves you little time to write. A computer virus. Acid reflux from all that coffee. A reader who gives you a "Pass" because he had a fight with his girlfriend the night before he read your script. Pressure from your parents/spouse/friends to give up. You'll encounter even more dangerous obstacles of the internal kind. Procrastination. Laziness. Writer's block. Insecurity. Fear of failure. Self-doubt.

And then there's your nemesis, Rejection. One of the fiercest villains you'll ever encounter, Rejection can sucker-punch you with a dismissive form letter or blindside you with scathing criticism. He can also deliver his most dastardly blow of all: silence. Rejection will seem, at times, invincible.

But lest ye forget, you have allies: the manager's assistant who said she liked your story idea; your high school English teacher who always encouraged you to do something with your writing; and let's not forget Dolores at the diner, who comes over to refill your coffee mug whenever she sees your eyes starting to droop while you clack away on your laptop.

You also have discipline on your side. As Woody Allen said, "Eighty percent of success is showing up." You show up at the café or your desk or wherever you prefer to work every single day. No matter what. Because the more you write, the more skilled and confident you'll become. Your voice will get stronger and more original, and as a result, your screenplays will get better and better.

And, most important of all, you have the one secret weapon that rivals the Excalibur of King Arthur, the .44 magnum of Dirty Harry, and the light-saber of Luke Skywalker. You have Perseverance. All heroes and successful screenwriters possess Perseverance. They stay the course and soldier on through the gauntlet of grueling tests and trials. They try every path and backalley in their quest because they never know which one will lead to that magic moment when they finally manage to slip past the velvet rope and enter the realm of Moviedom.

So how will your story end? You are the protagonist. The outcome is in your hands.

Stepping-Stone: The Pitches

Write a killer logline for your own movie. (You get only one or two sentences.)

Write a killer one-paragraph pitch for your movie. (You get no more than 125 words.)

Write a killer one-page synopsis of your movie. (You get no more than 500 words.)

SAMPLE SCREENPLAY TITLE PAGE

NOIR

by

Michael Cortez

Michael Cortez

1264 Oak Street

Toledo, OH

419-555-8553

excalibur@yahoo.com

SAMPLE SCREENPLAY PAGE

FADE IN:

EXT. DESOLATE STREET - NIGHT

Fog. A diner. A Dumpster. Way past the hour when anyone should be out and about, at least for this neighborhood.

A man turns a corner and strolls onto the street. This is FRANK MERCHANT. A fedora shadows his face but we can tell that's he's tough. He'll remind you of Sam Spade, perhaps a little nicer and slightly dumber.

He stops, checks his watch, then takes a look at the faded sign on the diner's exterior — Nite Owl Café. This is the right place.

Merchant taps his foot, waiting, maybe a little on edge.

He reaches inside his trench coat, pulling something out. A stick of gum. He unwraps it, slips it in his mouth.

A sound. He turns. A rat scurries under the Dumpster.

But wait, that wasn't it. From somewhere comes a muffled moan.

Merchant strides to the Dumpster, opens it.

Inside lies an elderly man, elegant in a white suit, bound and gagged. This is PROFESSOR VLADIMIR STANISLAV.

Merchant removes the gag.

STANISLAV

(thick Russian accent)

It's a trap, Frank.

Eyeballing the man. Is he speaking the truth? Merchant hoists Stanislav out of the Dumpster, removing the binding.

STANISLAV (CONT'D)

Hey, Frank, might you have a cigarette I can borrow?

FRANK

Sorry, Professor, I'm trying to

quit.