CHAPTER 2 Plot: The Path of Action

BY DANIEL NOAH

I love John Carpenter's horror flick, The Thing (written by Bill Lancaster). The film opens on the vast emptiness of the Antarctic, nothing but snow and ice, far as the eye can see. A Norwegian helicopter roars out from behind a mountaintop, upsetting the quiet. The chopper is in pursuit of a beautiful husky that's leaping across the boundless white. Then, inexplicably, a guy in the chopper takes a shot at the dog. The husky darts to a nearby American camp, where a group of scientists are posted. The helicopter lands and the Norwegians charge the camp, firing wildly at the husky. Chaos ensues and the Norwegians are killed. Bewildered, the American scientists take in the gentle dog.

The scientists soon realize the dog is not as innocent as it seems. In fact, it's not even a dog. It's an alien species that can mimic the form of any living creature it comes into contact with. And if it mimics you—you die. By the time the scientists figure out what's happening, the "thing" in their camp might have mimicked any one of them. It would look exactly like its victim. Talk like him, move like him, know everything he knows. But this perfect duplicate is far from a man; it's a deadly creature intent on destroying anyone who exposes it. No one can be trusted. Everyone must be feared. Completely isolated, nowhere near civilization, they've got to smoke the creature out from hiding before it kills them all.

The Thing is a horror movie and brain-teaser rolled into one, like H. P. Lovecraft coupled with Agatha Christie. Even as you're clutching your popcorn, bracing for the next shock, your brain is working overtime while you desperately try to piece together who's who, what's what, and, most important. . . what will happen next.

This powerful need to know what will happen next is the stuff of a great plot. Plot is what keeps us on the edge of our seats, mentally alert in anticipation of the twists and turns that surely await us. And a great plot isn't only necessary for a supernatural nail-biter like The Thing. Plot is what keeps us watching any kind of movie, regardless of how sensational or how subtle it might be. That's the key thing plot does. It keeps you watching.

So what is a plot?

A plot, literally, is the sequence of events that comprise a story. Those events aren't random, even in the most "lifelike" movies. Although many films reflect real life, good plots have little in common with the way real life actually unfolds. Real life, seen in a purely naturalistic way, is boring. If you don't believe me, get your hands on a copy of Andy Warhol's experimental film Sleep, five and half hours of a man—you guessed it—sleeping. What a plot does is reorganize real life, omitting the boring parts, emphasizing the dramatic parts, and artfully arranging events so as to keep an audience riveted for two hours or so. Nonstop.

Let me tell you something: Plot is tough. Possibly the toughest part of writing a screenplay. And possibly the most important, too. I sometimes spend days on end tinkering and experimenting, desperately trying to figure out how to arrange the events of my plot in a way that makes sense. Almost every time I start a new screenplay, I feel so daunted by plot that I convince myself I'm all washed up, finished in this business forever. But then, inevitably, I crack it. All those blurry ideas snap into sudden focus. What seemed so complicated before becomes very, very simple. You'll feel that rush of clarity, too. But it won't come from magic. In fact, it'll come from something closer to the careful and deliberate process of a scientist. There are time-tested principles (ancient, really) to help you get there. I'm now going to walk you through them, step by step.

Major Dramatic Question

At the center of every good movie there is a single driving force around which all other elements gather. It has the rage of a hurricane, the focus of a cougar, the horsepower of a Lamborghini. It's not the movie's star. It's not a special effect. It's not the most awe-inspiring action sequence or the most tearjerking dialogue. It is deceptively simple, so sly and stealthy, you don't even know it's there.

It's a question.

Sure, a good story raises lots of intriguing questions, but there is one question at the white hot center of all the others. This is the "major dramatic question," or MDQ for short. Every good story has its unique MDQ. Think of it as the story's nucleus. It's a centrifugal force that propels the story along its path of action, accelerating it steadily and breathlessly toward a climactic conclusion. And once the MDQ is answered, the story is over.

You want one of these for your story, don't you? Let me show you how to find it. The MDQ is comprised of three primary parts.

Protagonist

Most stories revolve around a single character, known as the protagonist. Really, protagonist is just a hifalutin term for the main character. Your protagonist is the primary player, the one whose story it is, whose desires, actions, and predicaments drive the plot. He or she is at the center of the events, the most important person. In Gone with the Wind, it's Scarlett O'Hara. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, it's Indiana Jones. In Silence of the Lambs, it's Clarice Starling. You get the idea.

Why do movies have a protagonist? Because it helps the audience to have a single character whom they can follow and identify with. To share his burdens. To invest in her dreams. We struggle along with Scarlett. We cheer on Indy. We fear for Clarice. It's easier for us to feel something if we're experiencing it alongside a single character, rather than several. Occasionally a film has more than one protagonist, and we'll discuss that later. But most movies have just a single protagonist, and until you're experienced with screenwriting it's best to stick with one.

It's important that you know your protagonist. His deepest thoughts, her most intimate feelings. But the visual nature of movies means that the screenwriter's job is to take all those thoughts and feelings and externalize them into forms that can be seen and heard. Your protagonist's thoughts and feelings must be represented as action. And that action needs direction.

Goal

Your protagonist's actions should focus on a single, overarching goal that he or she pursues throughout the story. While the protagonist may act on smaller objectives along the way, that primary goal is the one that keeps him or her pushing forward at all costs. Once that goal is achieved—or not—the story is over. For example, Scarlett O'Hara's goal in Gone with the Wind is to win Ashley Wilkes for herself. Indiana Jones's goal in Raiders of the Lost Ark is to obtain the legendary Ark of the Covenant. Clarice Starling's goal in Silence of the Lambs is to catch the serial killer, Buffalo Bill.

The goal should be something that the protagonist desires fiercely. The whole movie will turn on this goal so it had better be something terribly important. Important enough to drive the protagonist and hold the audience from start to finish.

Put the protagonist and goal together and you form the major dramatic question (MDQ), as such:

Will Scarlett win Ashley?

Will Indiana Jones obtain the Ark of the Covenant?

Will Clarice catch Buffalo Bill?

Notice how simply I stated those goals. A goal should be a model of simplicity.

A clear goal keeps the protagonist—and the story itself—on a directed path. The audience needs to have a sense of what the protagonist is after and to be able to follow how well he or she is progressing in pursuit of the goal. Even a sprawling epic like Gone with the Wind always stays connected to Scarlett's one goal of winning Ashley.

The goal should also be tangible, meaning something external and specific. It would be too abstract if Indiana Jones were seeking "to maintain the balance between good and evil." That would be hard to dramatize, hard to capture on film. It would be too broad if Indy's goal were simply "to have a good bout of adventure," or even "to defeat the Nazis." These goals aren't achievable in specific ways. "To obtain the Ark of the Covenant" works much better because it's something we can easily see Indy acting toward in external, specific, concrete ways. We can watch the struggle, and Indy's success or failure will be unmistakable. He will either get the Ark or he won't. That's a key point. The MDQ should be a question that can be answered with a firm "yes" or "no."

Though the goal itself should be simple, there may be a world of complexity beneath it. In fact, often there is a deeper desire underlying the goal. Something more abstract and internal. In Silence of the Lambs, for example, Clarice's deeper desire is to silence the lambs whose screams haunt her from the night she witnessed their slaughter on her uncle's farm. This is why she is training to be an FBI agent and it's why she wants to catch Buffalo Bill before he takes another victim. The internal desire is often the emotional root of the external goal, signaling what is really at stake for the protagonist. Clarice wouldn't be able to spend the entire movie trying to silence the screams in her mind—no way to show that—but her deeper desire adds depth to her surface goal of catching Buffalo Bill.

Simple, and yet complex.

The MDQ is the thing that keeps us watching, wondering how things will turn out. By the end of the movie, there will be—there must be—an answer to the MDQ. A "yes" or a "no." Indy and Clarice both manage to achieve their goals. Scarlett fails, realizing she will never possess Ashley and that he wasn't the right mate for her anyway. Sometimes, protagonists realize that the goal wasn't really what they needed after all.

Conflict

The protagonist acts to achieve the goal. But he or she should come up against obstacles, opposing forces that block the fulfillment of that goal. When obstacles get in your protagonist's way, there is conflict. Conflict is an essential part of the MDQ equation because it's what makes a story dramatic. Most of us don't want to watch a movie about someone sleeping. Or even achieving the goal without breaking a sweat. If it were easy for Scarlett to win Ashley, or for Indy to obtain the Ark, or for Clarice to catch Buffalo Bill, these movies would be absurdly short and painfully dull.

Just as a protagonist pursues a primary goal through the story, he or she usually acts against a primary obstacle. The primary obstacle often comes in the form of a person, an antagonist. Most people think of an antagonist as the bad guy, and often it is. Darth Vader is a classic antagonist whom we love to hate. But the antagonist can also be a perfectly decent person who happens to be at cross-purposes with the protagonist, such as Carl Hanratty, a federal agent on the trail of a counterfeiter in Catch Me If You Can. So whether he wears a black cape or a cozy felt hat, the character who most stands in the protagonist's way is the antagonist. The primary obstacle doesn't need to be a single person, or even a person at all. It can take many forms: a beast (Jaws), nature (The Perfect Storm), machinery (2001), an empire (Star Wars), or even a whole world (The Matrix). All of these are the primary obstacles that block protagonists from achieving their goals.

Though there is only one goal, there may be a multitude of obstacles. In fact, the more obstacles, the better. Many of these obstacles will come from an antagonist but some may emerge from elsewhere. Not only does Scarlett need to contend with the fact that Ashley is happily married to Melanie, but she's got the Civil War, a dying way of life, a plantation, starvation, and three husbands to deal with. In the context of the story, these are all obstacles to Scarlett's primary goal of winning Ashley.

Conflict comes in two forms—external and internal. External conflicts come from obstacles exterior to the protagonist, like the antagonist. Internal conflicts refer to struggles within the protagonist's own mind. Movies need external conflicts because they are easier to portray on screen, but the richest characters have both external and internal conflicts. In addition to Clarice's external obstacles to catching Buffalo Bill—discovering his identity, soliciting information from Hannibal Lecter, deciphering clues, tracking him down—Clarice must overcome her fears of the dark side of human nature, as well as her insecurities about being a woman in a man's job and of being a "country rube." These internal conflicts give the story more psychological depth.

Conflict is the most indispensable element of a good story. It's what happens when the unstoppable force meets the immovable object. A crashing together of contrary intentions that rivets us and keeps our eyes locked on the screen. Remember this: Movies are not about casual events in a life. They are about the most crucial, challenging, earthshaking events.

MDQ Illustrated

Let's take a look at the MDQ of Die Hard.

The protagonist of Die Hard is John McClane, a New York City cop who has come out to L.A. for the Christmas holidays to visit his estranged wife. He arrives at the corporate high rise where his wife is attending a lavish Christmas party hosted by her employer.

Quick, what's McClane's goal in Die Hard? Did you say: To reconcile with his wife? Bzzz. Wrong guess. Read on.

Soon after McClane arrives, a group of terrorists seize the building, taking everyone inside hostage. Everyone except for McClane, who slips into a stairwell undetected. It's now up to him, and him alone, to save the hostages. Because he's the only one who knows. Because he's the only one who can. But most of all, because his wife is one of them. That is McClane's goal: to free the hostages.

Thus, the MDQ of Die Hard is: Will McClane free the hostages?

While McClane certainly came to L.A. to reconcile with his wife, the need to stop the terrorists takes precedence. That's what McClane will be doing throughout the movie—trying to stop the terrorists in order to free the hostages. He will free them or not by the end of the story. That's how you know a goal when you see it. It's the thing the protagonist is in pursuit of for the majority of the movie.

Is there conflict for McClane? Plenty. The terrorists are led by Hans Gruber, the mastermind of a brilliant plan to distract the authorities with the hostages long enough to break into the company vault and make off with millions in untraceable bonds. Hans is the primary obstacle, the antagonist. But there are many other obstacles as well. In addition to Hans, there is the entire team of terrorists, who are well equipped, well trained, and ruthless. McClane has no way to call for help. When he finally gets help, the authorities only make things worse. And McClane is without shoes, which is no small obstacle on a battlefield. (There are even more, but you get the idea.) These are all external conflicts. There's some internal conflict, too, namely McClane's need to keep his spirits up while he wages a war he can't possibly win.

Is there a deeper desire underlying McClane's goal? In a sense, yes. McClane's desire to reconcile with his wife is actually a subplot (which you'll learn about in a later chapter), but this yearning also does work as a kind of deeper desire under McClane's primary goal. There is a sense that if he can save the hostages he might be able to eventually work things out with his wife. This underlying desire adds poignancy to McClane's mission and it's part of what makes this story so powerful.

Let me also say this: It's best if your MDQ can be answered in a compressed amount of time. Some stories need to sprawl over years, or decades, but most unfold in a short amount of time—weeks or days. This compression of time adds a level of tension to the plot. Die Hard, for example, occurs in a single night.

Three-Act Structure

Once you've pinned down the MDQ of your screenplay, it's time to figure out how it will play out over the course of the movie. In other words, you need to determine the plot. The most significant element of plotting is figuring out the structure. The structure is the overall shape, or architecture, of the story. As you begin to design your screenplay, you must apply a kind of dramatic structural engineering that will help hold everything together.

Screenplay structure begins with the simplest of concepts, so absolute, so rooted in universal truth, it's downright philosophical. Call it the Rule of Three. Most everything in life can be broken into three parts: the beginning, the middle, the end. Your experience of reading this book fits this model: You buy the book, you read it, you begin writing a brilliant screenplay. A day consists of three parts: morning, afternoon, night. Life itself even follows the Rule of Three: you're born, you live, you die. Beginning, middle, end. One, two, three.

This empirical law of nature is the basic tenet of all storytelling. Aristotle introduced this concept more than five thousand years ago in his treatise on tragic drama, The Poetics. He writes the following about works of drama:

. . . they should be based on a single action, one that is a complete whole in itself, with a beginning, middle, and end, so as to enable the work to produce its own proper pleasure with all the organic unity of a living creature.

In other words, the idea of beginning, middle, and end is innate to our experience of living, and so it is the most organic format for us to use in stories. The idea of beginning, middle, and end can be found in any mode of storytelling, from campfire tales to Greek mythology to movies.

In screenwriting, we formalize the beginning, middle, and end into something called acts. Most every screenplay has three of them—Act I, Act II, Act III. These acts have specific functions. Act I is where the story is set up. Act II is where the conflict escalates. Act III is where the story climaxes and resolves. Everyone in the movie business talks about screenplays in terms of the three acts, so you need to become well versed in this concept.

Let's give it a visual. The acts look like this:

Now, these acts aren't like the acts in a play, which are clearly marked by blackouts and intermissions. The act breaks in movies are invisible to the audience. But that invisibility doesn't make the acts unimportant. Quite the contrary; the audience expects the three-act structure to be there. They might not know it, but they feel it. They crave the progression of story that a three-act structure delivers. Never forget that movies are designed to be watched in a prescribed period of time, unlike the experience of reading a book, which can be set down, picked up, set down again. A film owns its audience, and with that ownership comes the responsibility of holding interest. This is why the structure in screenplays is emphasized so much more than in novels. The viewer's interest must be hooked for every moment of a film's running time. Without the three acts, people would grow restless.

Before we move on, it's crucial that you understand how screenplays relate to time. One page of a screenplay equals approximately one minute of screen time. The average length of a feature screenplay runs between 90 and 120 pages, which equates to the average running time of a feature film, 90 to 120 minutes.

The length of the acts breaks down roughly like so:

Act I: 30 pages

Act II: 60 pages

Act III: 30 pages

(It has become fairly common now for third acts to be a bit shorter than first acts. So, really, you can think of Act III as running 15 to 30 minutes.)

30, 60, 30. That's a lot easier to think about than a clean 120. But that's still three amorphous blocks of screen time that need to be filled. Fear not: Just as morning, afternoon, and night are determined by the position of the sun, certain events define each act and help them shift from one phase to the next.

Major Events

Remember, plot is a sequence of events. But what is an event? Simple enough. An event is when something happens. A baby is born. A car breaks down. You stub your toe. Events.

In drama, an event effects change. A change in circumstance, in feeling, in knowledge, in perception. A character enters a scene with a goal in mind. Faces some obstacle, large or small. Struggles with the obstacle, then either overcomes it, or doesn't. The result of the conflict sparks a change, creating a new situation. In the next scene, the character acts against a new obstacle based on the new situation, and another change occurs. Then another. And another. And so it goes on. Each event—each change—is a link on a chain that will comprise your plot. The entire movie should be linked through direct cause and effect this way.

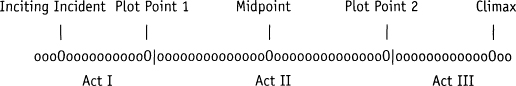

So really your plot may look more like this:

| ooooooooooo| | ooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo| | oooooooooooo |

| Act I | Act II | Act III |

Mostly you will use two kinds of events, events that effect either a negative or a positive change. An example of a negative event would be: A woman on the hunt for her husband's killer is suddenly blamed for the crime. An example of a positive event would be: A boxer learns he's getting a shot at the title. If the event is totally neutral, with no real positive or negative change, it's probably not worth including in the screenplay.

Each link on the chain is an event, and each event is a change. But some of those events are especially important. These major events represent radical change. These radical changes are what really get your plot going and what cause one act to spring into the next. Working with these major events will also make it easier for you to plot your story because they act as guideposts that help steer your protagonist along his or her path of action.

Warning: I'm now going to introduce some fancy technical terms for the major events. These terms aren't standardized; different screenwriters and gurus have their own vocabulary. But the terms I'm using are perfectly acceptable and they're known to most people in the business. It's also going to sound like I'm giving you a formula because I'm going to tell you exactly where specific events should fall in your story. It is a formula, and it isn't. After all, anyone can follow directions. It's the way you follow them that will make your story distinctive. The specific placement of these major events is to ensure that you keep your story tightening and tensing before the audience tunes out. While these are time-honored principles, they are not to be followed slavishly. And, by all means, whenever I mention a page number on which something should happen, factor in a grace margin of ten pages or so. This is not an exact science.

Full disclosure: Some screenwriters consider these terms and concepts anathema to good writing. And sometimes the writer's intuition is more important than any technique that can be learned from a screenwriting book. But the fact is, most screenwriters consider these concepts essential. Whether they consciously follow these schemas or if they work from the hip, one cannot deny that an overwhelming majority of movies follow most, if not all, of these principles. And once you learn all this stuff, you're free to forget about it, as many experienced screenwriters do.

Okay, ready? A movie usually has five major events: inciting incident, plot point 1, midpoint, plot point 2, and climax.

Here's another chart that shows you approximately where these major events fall in the three act structure.

These events usually fall approximately on these pages in a screenplay:

Inciting incident: page 10

Plot point 1: page 30

Midpoint: page 60

Plot point 2: page 90

Climax: a few pages from the end

Sometimes these events are easy to spot in a movie, sometimes they're a little more slippery. Occasionally, they're not there at all (but only very occasionally). And it's even possible for knowledgeable people to disagree on which events are which in a given movie. As I warned, this is not an exact science.

Now let's take all of this out of theory and see how it works in an actual movie.

Plot Illustrated

I'm going to illustrate plot by breaking down Die Hard. If you're not a fan of action flicks, relax. Everything I'm about to say applies to the vast majority of films, but the classic nature of Die Hard’s plot lends itself to a very clear analysis of the fundamental plot principles.

Lights down. Let's go.

Act I

Most screenplays begin with a brief lead-in, lasting around ten pages. In these pages we meet the protagonist. We learn a little about the kind of person he is, what makes him tick. We are also introduced to the world in which the story is set. And we're shown any other key elements of the story we need to know before the plot gets revved up.

In the lead-in of Die Hard, we meet the protagonist, John McClane. He's a wisecracking New York cop who's in Los Angeles for the holidays in hope of reconciling with his estranged wife, Holly, an executive at the Nakatomi Corporation. He meets up with Holly at a private Christmas party in Nakatomi Plaza, a sleek, modern high rise.

McClane couldn't be more out of place here, dressed down and strapped with a gun, as well-tailored "California eccentrics" swarm around in revelry. At the party, we meet several key supporting players, including Holly's boss, Mr. Takagi. We also learn that the operations of the entire building are controlled by a computer, and that the partygoers are the only inhabitants in the otherwise empty high rise.

McClane and Holly talk. It's clear that they love each other and share a desire to patch things up. But there are unresolved issues over Holly's decision to move across the country for this job. It's easy to see how different their two worlds are, and the chasm they must somehow bridge if they are to save their marriage.

That's the big stuff we learn in the lead-in. But there are even more details, little kernels which will pop later in the story, from Holly reverting to her maiden name, to McClane removing his shoes in order to follow his plane-mate's advice to relieve stress by making "fists with his toes," to the Rolex given to Holly as a company gift. These tidbits may seem inconsequential in the moment, but in a well-plotted screenplay nothing is arbitrary. Every single thing is included for a reason.

The lead-in culminates with the first major event, the inciting incident. The inciting incident is the event that sets the story into motion, that will lead the protagonist toward the pursuit of the goal. This is often the first appearance or hint of the primary opposing force. The normal course of the protagonist's life is almost always disrupted here, for better or worse.

In Die Hard, the inciting incident occurs when Hans Gruber and his band of terrorists invade the building, locking it down, seizing control of the computer system, and cutting off all outside communication. (This happens 18 minutes into the movie, a little later than usual, but we get an ominous glimpse of the terrorists approaching at 14 minutes.) Hans and his men burst into the party and take everyone in the building hostage. There's no way to call for help (this is pre–cell phones), and no route to escape. Hans Gruber is in total control.

Except over McClane, who has slipped unseen into a stairwell. He is now the only free person who knows what's happening in Nakatomi Plaza, as well as being the only person in a position to do anything about it.

McClane lies low, trying to keep out of sight long enough to figure out what to do. After giving a speech to the hostages, Hans takes Takagi into an empty office. He demands that Takagi reveal the computer code that will unlock a vault containing 640 million dollars' worth of bonds. McClane creeps near and watches from hiding.

At the end of Act I comes the next major event, plot point 1. Plot point 1 is usually an even more drastic event than the inciting incident. This is the event that makes the pursuit of the goal mandatory or absolutely irresistible for the protagonist. The goal may first surface here, or the idea of it may have existed before, but here it becomes essential. The inciting incident and plot point 1 are usually closely related, working like a one-two punch to solidify the goal; once plot point 1 hits, the protagonist cannot walk away from that damned goal.

In Die Hard, plot point 1 occurs when Takagi refuses to disclose the code and Hans shoots him in the head. (It happens 31 minutes into the movie.) This simple action changes everything. McClane now knows that he's dealing with cold-blooded killers. Clearly the hostages are in serious danger. Before this moment, McClane could have decided to wait things out in hiding. Now he knows he must take action or people will die, maybe even Holly. McClane has his goal and we have our major dramatic question: Will McClane free the hostages?

Plot point 1 appears right at the end of Act I, but don't think of it as an ending so much as a springboard into the next act.

Act II

If Act I consists of setting up the conflict, then Act II is where that conflict plays out and escalates. From here on, it's all about the protagonist fighting against the obstacles to achieve the goal. It's the longest act, and you'll need plenty of conflict to sustain it.

Hans has his tech specialist set about breaking the computer code, a complex routine that requires going through seven computerized locks.

McClane's first priority is to alert the authorities to the situation in the building. He trips the fire alarm, but the trucks are called back when Hans calls it off as a false alarm.

Now Hans knows there's a rogue loose in the building whom he is going to have to deal with. McClane's cover is blown. Hans sends a man after McClane, whom McClane promptly kills. Finding a CB radio on the dead man, McClane calls a police dispatcher. McClane can't get the dispatcher to understand the situation, but, nevertheless, she sends a squad car to investigate. As McClane waits for the cavalry, Hans, having listened in on his distress call, directs his men to search the building and smoke McClane out.

Notice how every event in a well-plotted story is part of a chain of cause and effect. McClane trips the fire alarm, which causes Hans to send a man after McClane, which allows McClane to get hold of a CB radio and call the police, which results in Hans launching a manhunt. Also notice how the events are alternating between negative and positive for McClane.

With several terrorists in pursuit, McClane slyly evades them, climbing down an elevator shaft and crawling through an air duct. Soon two of the bad guys catch up with him, but McClane kills them both.

A lone policeman comes to the building but, after talking to a terrorist posing as the security guard, he decides nothing is wrong and heads out. McClane's plan to alert the authorities is failing.

Now, then. Act II is usually divided by a major event called the midpoint. Falling smack-dab in the middle of the act, the midpoint is not only the center of Act II, it's also the center of the entire story. By virtue of where the midpoint falls—dead in the middle—it needs to accomplish a bit more than a simple negative or positive change for the protagonist (though it usually does that, too). Often the midpoint brings about a shift in tone, or a slightly new vibe. You don't want a story to feel static; you want it to feel like it's evolving, and that's what happens here. Also the midpoint is usually a knockout moment, a spike of energy to adrenalize the story so the middle doesn't sag, but actually peaks. Most midpoints tend to be extremely memorable, something that people consider one of the best parts of the movie.

Here's the midpoint of Die Hard. Seeing the cop drive away, McClane hurls the dead body of one of the terrorists from a window and onto the hood of the patrol car. (This happens 57 minutes into the movie.) Needless to say, this catches the cop's attention and he calls in reinforcements, just as McClane wanted him to.

This represents a positive change; McClane achieves his objective of getting help from the outside. The larger significance of this midpoint is that it alters the playing field to pull a radical new set of factors into the world of the story. Until this point, the characters and the action have remained fairly isolated. It's almost as if the inhabitants of Nakatomi Plaza have been the only people in the city. But now the grounds of the plaza will be swarming with cops, FBI agents, and television crews broadcasting the story. Suddenly the building seems to have become the center of activity in all of Los Angeles. It's a whole new dynamic. A new vibe. Plus, the body landing on the cop car in Die Hard is one of the movie's most talked-about scenes.

Even so, McClane is still the only one inside the damn building who can do anything. He begins to carry on radio conversations with Powell, the cop who first investigated the building, feeding him information, and he even has a few radio talks with Hans, trying to antagonize him into losing his cool.

McClane also notices a bunch of detonators and a plastic explosive in the bag of one of the dead terrorists. What are those for? McClane doesn't know, but he realizes this doesn't bode well for the safety of the hostages. This is a good moment to point out that the conflict should continually escalate throughout Act II, the obstacles growing increasingly more formidable. The fact that the terrorists have explosives ratchets up the stakes.

Soon a police SWAT team attempts to charge the building, but the terrorists hold them at bay with their weapons, including a missile launcher. To prevent the cops from getting shot, McClane ends the siege by tossing the plastique down an elevator shaft, causing a massive explosion.

Then, in a beautiful scene of cat and mouse, McClane and Hans meet face to face and engage in a complex game of deception. (McClane has never actually seen Hans, and Hans takes advantage of this fact by pretending to be a hostage on the run.) Neither succeeds in killing the other, but Hans wins the round when McClane is forced to leave the detonators (the only ones) behind while fleeing a terrorist who gets the best of McClane by spraying him (and his bare feet) with shattered glass. It's worth noting that this first meeting between the protagonist and antagonist isn't about physical force, as you might expect from an action film. Instead, it's a battle of wits between two extremely cunning players. And it's riveting.

As we approach the end of Act II, we hit plot point 2. At plot point 2, the stakes usually escalate to the highest level yet, and this pushes the protagonist toward a final confrontation with the primary obstacle. Whatever is going to happen is going to happen imminently and decisively.

Plot point 2 is usually (though not always) a major victory for the opposing force and a major setback for the protagonist. In fact, plot point 2 usually brings the protagonist to his or her lowest point in the story. It's often a crossroads, a do-or-die moment, when the protagonist must choose to either back down or plunge ahead with renewed strength. Protagonists will always choose the latter path.

Plot point 2 in Die Hard occurs when the FBI cuts the power to the building, which opens the seventh and final lock on the vault, something Hans had known would happen all along. (It happens 103 minutes into the movie, which is later than usual, but Die Hard runs a little over two hours.) Hans is at the final stage of his plan, which we discover means more than just making off with the loot. He's planning on ushering the hostages to the roof and blowing them sky high. Hence the need for the explosives and the detonators. The authorities will assume that the terrorists also perished in the explosion, leaving the bad guys to flee in peace. With the vault open, it's now a countdown to mass death. (A ticking clock is always a great device for holding an audience.)

At the same time, McClane reaches his lowest point. He doesn't yet know about the open vault and evil escape plan but he senses doom, telling Powell over the radio, "I'm getting a bad feeling up here." He's on the ropes. Exhausted, pulling shards of glass from his bloody feet, he instructs Powell to tell Holly that he loves her, and to apologize for all the mistakes he made in their marriage. Knowing he will probably die soon, McClane is forced to face the failure of his marriage and his failure to free the hostages. He is very close to giving up. But he doesn't give up. That ain't McClane's style. Might as well go down swinging and hope for that lucky punch.

Just as plot point 1 springs us into Act II, plot point 2 springs us into Act III.

Act III

The first part of Act III usually contains a compressed series of events that escalate to the final confrontation.

When McClane sees explosives wired to the roof of the building, he realizes what Hans plans to do with them. The hostages are now being evacuated to the roof. Time is short. At this same moment, Hans finally discovers that Holly is McClane's wife, a fact that previously eluded him due to Holly using her maiden name. Hans seizes Holly as insurance should McClane get in the way of his plan's final stage.

In a spectacular sequence, McClane clears the hostages off the roof. He saves their lives but almost loses his own as an explosion forces him to dive off the edge of the rooftop. He dangles from a fire hose, which he uses to smash through a window and reenter the building just seconds before falling to certain death.

The hostages are safe. All, that is, but one: Holly. McClane knows that this is his last and only chance to take Hans down and save his wife.

Which brings us to the climax. This is it. The big showdown. The final confrontation with the primary obstacle. Your hero has won and lost some battles, but this is the one by which he will win or lose the war itself. Whatever happens here is the be-all and end-all of the story. There will be no more chances. The MDQ will be answered. The goal will be won or lost forever. And know that the protagonist must take the final action himself. It wouldn't be right if it were the police or FBI who ultimately saved the day. It must be McClane.

In Die Hard, the climax occurs when McClane invades the vault, interrupting Hans's getaway. At gunpoint, McClane pretends to surrender, dropping the machine gun he carries. With Hans off his guard, McClane grabs a handgun duct-taped to his back and shoots Hans in the chest. Hans crashes through a window and stops his fall only by grabbing onto Holly's wrist. Both Holly and Hans are about to plunge forty stories down. McClane unclasps the watch on Holly's wrist, the very thing Hans clings to, and Hans plummets downward to a violent death.

McClane has saved the hostages, including Holly. The MDQ has been answered with a heroic "yes." McClane wins.

There's still one final piece to a plot, the resolution, which gives us a glimpse of the story's aftermath. Often it speaks to that deeper desire underlying the protagonist's goal, hinting at what is to come for the protagonist.

In Die Hard, the resolution comes when McClane and Holly drive off merrily together in the limo. We sense they now know that if Hans Gruber and his band of terrorists couldn't keep them apart, petty marital problems don't stand a chance.

The Subtle Plot

To show you how prevalent these plot principles are, let's analyze them in relation to a movie that couldn't be more different from Die Hard. That would be Sideways.

Die Hard is a classic Hollywood film, filled with slam-bang action, heroes, and villains, and the whole nine yards. Sideways is a subtle, nuanced, character-driven, indie film. To illustrate the difference, Die Hard features a scene in which the hero picks glass out of his bleeding feet while battling terrorists; Sideways features an entire scene in which the hero clips his toenails. Most indie films (not to mention foreign films) fall into the second category. These movies still usually follow the basic plot principles but everything is, well, more subtle.

Take, for example, the protagonist's goal. Previously, I told you that goals should be clear and tangible, with often a more abstract, deeper desire underneath them. Subtle movies often do away with the external goal and use something more internal and vague as the primary goal. In other words, the deeper desire becomes the protagonist's goal. While external goals lead to plot-driven stories, internal goals lead to character-driven stories. Die Hard is a good example of the former, and Sideways is a good example of the latter.

The protagonist of Sideways is Miles, a middle-aged school-teacher and unpublished novelist whose wife has divorced him. He's a man whose train has left the station without him aboard. The two things that mean the most to him, his writing career and his love life, are in shambles.

The goal in Sideways is not nearly as easy to pinpoint as in Die Hard. In fact, I had to really dig to figure out what it was. Miles needs some kind of success in order to get out of this dark period in his life. A publishing deal, a romance—anything. There are probably many ways to state what Miles's goal might be. Let's go with: to pull himself out of his rut. So the MDQ of Sideways is: Will Miles pull himself out of his rut?

The primary obstacle is also fairly abstract. It's not a person or a beast or an empire. The primary obstacle is failure itself. Being very much a character-driven movie, much of the failure is actually inside Miles's mind; it's not so much external events that cause his failure as his own self-sabotaging and fear. You could safely say that Miles's worst enemy is Miles. He doesn't even pursue his goal along a straightforward path of action. The desire is there, but he's afraid to go after it. In fact, Miles spends most of the movie sidestepping any situation that might put him face to face with failure.

But even when the goal is mostly internal and indirectly pursued, you still have to find ways to give the protagonist tangible objects of desire. Otherwise you would have nothing to show, nothing for the protagonist to do. There are a number of external expressions of Miles's goal of pulling himself out of his rut. His book is still being considered by a single publisher. And he's attracted to Maya, a waitress he knows from one of his favorite restaurants. If either of these situations were to end well for Miles, it might bring him out of his rut. Even though he doesn't pursue these objectives with the singular focus and tenacity as, say, John McClane, Miles isn't sleeping for five and a half hours, either. He's actively engaged in external goals and conflicts, just in more subtle ways.

Now let's look at how the MDQ is played out through the major events. Yes, Sideways does have major events, even if they are more difficult to spot.

In the lead-in to Sideways, we meet Miles and his best friend, Jack, as they set out for a weeklong getaway to wine country, their last hurrah before Jack's coming wedding. You could say the inciting incident is simply when Miles and Jack set off on the trip, as claimed by one of my colleagues in chapter 8 (see, I told you knowledgeable people can disagree on this stuff). But I'm going to take a leap and say that the inciting incident is when Miles sees an old photo of himself as a child in his mother's room. Gazing upon his younger self, he is struck by how far he is from fulfilling his dreams—and how close he is to failure. (This happens 15 minutes in.) But, truth be told, a strong argument could be made that Sideways has no distinct inciting incident. Remember, none of this is an exact science.

Plot point 1 arrives when Miles learns that his ex-wife is getting remarried (which happens 35 minutes in). This represents a enormous setback, as Miles has harbored hopes of a reconciliation. He can no longer live in denial, foolishly thinking he'll get his wife back. Though he doesn't exactly spring into action, it's clear that he must find something soon to get his life back on track.

Moving into Act II, Jack drags Miles into a complex web of lies as he pretends to be single in order to woo Stephanie, a woman he meets at a winery. Stephanie has a friend, Maya, whom Miles gets paired with. Despite Miles's discomfort with Jack's charade, Miles is attracted to Maya.

The midpoint arrives at the end of their double date. As Jack and Stephanie disappear into Stephanie's bedroom, Miles manages to edge haltingly toward making a connection with Maya. (This happens 60 minutes in.) Getting in good with Maya, a woman he is attracted to, is a big deal, a boon to Miles's goal of pulling himself out of his rut. It puts him on the upswing, giving him the nerve to go after Maya through the rest of the act. Also, true to midpoint form, Miles's Pinot Noir monologue here is one of the most talked-about moments in the movie.

Quick digression. It's also in this sequence that Miles mentions that's he's saving a vintage bottle of wine, a Cheval Blanc, for a "special occasion." Though this information in itself isn't a major event, it is nonetheless an important setup for an event to occur later. I point this out to illustrate the deliberate way that specific information is dispensed, at carefully chosen moments, to lay the groundwork for later payoffs.

In Sideways, plot point 2 is a typically huge blow to the protagonist. Since Maya has now dumped Miles upon learning of Jack's charade, Miles's only hope is his book. He finally works up the guts to call his agent for a status report. His agent gently informs Miles that the final publisher has turned him down. (This happens 90 minutes in.) That's it for Miles. His ex-wife is getting married, Maya has dumped him, and his book is dead. There is no getting around his failure. Though Miles doesn't handle this moment well (he freaks out and guzzles the contents of a spit bucket), he doesn't fold up and die either. He stays on his feet.

Now we move into Act III. Following a few more adventures, Miles and Jack head back for the wedding. There, Miles finally has a face-to-face encounter with his ex-wife. She announces to Miles that she is pregnant with her new husband's child. It's a crushing blow, the biggest reminder yet of Miles's failure, and it seems like the final nail in his coffin. But then Miles takes a surprising stand against his failure.

The climax of Sideways is so subtle, you could blink and miss it. It arrives in a seemingly mundane scene when Miles finally drinks that Cheval Blanc '61. He drinks it all alone, without ceremony, from a Styrofoam cup in a greasy burger joint. Miles has given up on that special occasion to open this bottle. He's accepting his failure, letting go and moving on. It's here that Miles actually does achieve his goal of pulling himself out of his rut. Failure has been defeated, in a sense, because he's taken away its power to drag him down.

In the resolution, Miles receives a call from Maya, and the film ends with a hint that they may get together after all. Sometimes, letting go of broken dreams makes room for new ones.

See, everything is there. It's all just a little more subtle.

Take a Shot

Watch a movie. Any movie will do, but you want to watch it on DVD or tape. Try to identify the following: major dramatic question, inciting incident, plot point 1, midpoint, plot point 2, climax. You may not spot these things right away. You will do best by watching the movie straight through, then re-watching it to analyze how the plot fits together. (You can test yourself against our answers if you use one of the movies listed at www.WritingMovies.info)

Variations

It is advisable to stick with the tried-and-true principles of plot until you've completed a few screenplays. Even Warhol began as a realistic sketch artist before he moved on to all those soup cans and experimental movies. Once you know and understand the "rules," you can break them better. And it's good to break them. In fact, the greatest films, those written and directed by the true masters, are the ones most likely to flaunt the rules of conventional plot. Watch a movie like 2001 or Vertigo or The Godfather and you'll see plot rules broken left and right. Since it's usually enlightening to study the exceptions, let's look at some ways in which films use variations on the basics.

Multiple Protagonists

Some movies have more than one protagonist. For example, in Thelma & Louise we would be hard-pressed to claim that either Thelma or Louise is more central than the other. Together, they comprise "dual protagonists," that is, two protagonists who function as a single unit in pursuit of a common goal. Thelma and Louise share the common goal of trying to reach the border of Mexico before the cops catch up with them. (Thelma & Louise, by the way, is a good example of a goal that is not achieved.)

Dual-protagonist movies often fall into the "buddy" subgenre. Famous buddy films would include Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Lethal Weapon, Dumb and Dumber, and all those classic Bob Hope-Bing Crosby "road" movies. You might consider Sideways a buddy film, but in this case Miles is the clear protagonist; Miles and Jack definitely don't share a common goal.

Some films go beyond two characters to feature a team of protagonists who all work together toward a common goal. With team protagonists, though, there's almost always a lead protagonist around whom the others gather. For example, while Luke Skywalker is the clear lead of Star Wars, Han Solo, Princess Leia, Chew-bacca, the Droids, and Obi-Wan are all key characters who work with Luke to overcome the Empire. Some movies offer a variation on the typical team-protagonist setup. In Alien, for example, a team of characters share the common goal of survival as a really crabby alien invades their spacecraft and picks them off one by one. Only late in the film does Lieutenant Ripley emerge, almost by default, as the lead protagonist.

Then we have "split protagonists," where two characters have equal weight and equal claim on our affections, but are operating at cross-purposes with each other. Terms of Endearment is split equally between Aurora (the mother) and Emma (the daughter). Heat is equally split between Hanna (the cop) and McCauley (the crook).

What about the love story? The love story is unique in that it's a pinch of the dual protagonist, a splash of the split. It's dual in that the love story usually features two characters in pursuit of a shared goal (to be together), who often work against a common obstacle to that togetherness. But it's split in that the two characters often confront the obstacle at separate angles, perhaps even clashing with each other in the process. For example, in When Harry Met Sally . . . , both Harry and Sally are protagonists who share the goal of finding love, but each must first let go of a specific idea of love in order to recognize they have found it in each other. Not every love story, however, features two protagonists. In movies like Moonstruck and The Philadelphia Story, one of the romantic partners is the obvious lead.

Multiple Plots

If you think a multiple-protagonist plot is complicated, try one of these.

Some films contain a multitude of characters, each with equal weight, pursuing his or her own goals in separate plots. These are known as "multiple plot" or "ensemble" films. Together, the various stories form a kind of collage. The writer-director Robert Altman is the master of the ensemble movie, which he has perfected in such films as M*A*S*H, Nashville, and Short Cuts. Other notable examples of this kind of film would include American Graffiti, Do the Right Thing, and Magnolia.

Usually there is some overarching element that ties the plots together. For example, in Nashville, all the characters are attending a country-music festival in Nashville (a shared event). We meet a gallery of Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn denizens in Do the Right Thing on the hottest day of the year (a shared experience). Magnolia features a mosaic of stories about characters all haunted by their pasts (a shared theme).

Shifting Goals

Though I've told you that a protagonist must have one primary goal, there are great movies out there in which the goal seems to reveal itself in the first act, only to shift later in the story.

For example, in Tootsie, the protagonist, Michael Dorsey, masquerades as a woman, Dorothy Michaels, in order to get work as an actor. His initial goal seems to be to find work. But he achieves this goal at the end of Act I when, as Dorothy, he lands a plum role on a major soap opera. His goal then seems to be to get close to Julie (the actress he falls for). So it seems this movie has violated the golden rule of one driving goal for the protagonist. Has it? Well, yes and no.

If you look closely, you'll see that Tootsie is held together by a single goal: to maintain the masquerade. He must maintain the masquerade for the duration of his contract. If he fails to do this, he will ruin his reputation, his agent's reputation, shatter his friend Sandy's ego, and also do a little damage to his own actor's ego. Also, for most of the movie, maintaining the masquerade is the best way for him to get close to Julie. So, this is what Michael is doing in every scene: maintaining the masquerade. Only at the end does Michael realize he can no longer sustain the masquerade and keep his sanity, and so he unmasks on national television. Viewed in this light, Michael ultimately fails to achieve his goal, but he gives up on it for a good reason.

There may be plots where it's necessary for the protagonist's immediate goal to shift, as it does in Tootsie, but the plot will still work better if there is some kind of overarching goal that remains constant throughout the movie. This may be a concrete goal, like maintaining the masquerade, or a more abstract goal, like Miles's desire to pull himself out of a rut. The ongoing goal will keep your protagonist on a clear path.

Defying Chronology

Then there are plots that defy chronology in their unfolding. Pulp Fiction, for example, begins in one time period, then abruptly shifts back, then ahead, then back again. Part of the fun of the film is piecing together what's happening when, and in what order. The "meta-structure" even defies death itself as the character of Vince Vega is "resurrected" after his own demise. And how about Memento, which unfolds backwards, beginning at the end of a mystery and then backtracking through ten-minute increments to see how it all began? The effect is one that reflects the experience of the protagonist, who has no short-term memory; like him, we have no idea what happened before the moment we're in. Then there's Run Lola Run, which challenges its heroine to race across town in time to save her boyfriend from thugs—but when she fails, the movie "rewinds" to "start over" and give her two more chances to play it differently. Sort of like the three lives of a video game. Interestingly, even these nonchronological structures still have a clear beginning, middle, and end. They just do it in their own way.

The Shawshank Exception

The Shawshank Redemption is one of those movies that breaks almost every rule in the book.

A young banker named Andy Dufresne is convicted of the murder of his wife and her lover and sentenced to life in Shawshank Prison. Though we're initially unsure whether Andy committed the crime, we're certain that he's a good man to whom we want to see no harm come. Andy befriends Red, a seasoned con, and the two form an unbreakable bond as they endure their sentences. After almost twenty years together, Red discovers that Andy has been methodically and patiently tunneling to freedom since he arrived at the prison. Ultimately, Andy breaks out, Red is granted parole, and the two friends reunite on a beach in Mexico.

For starters, who's the protagonist? Andy is clearly at the center of the movie. Yet, most of the events are seen through the eyes of Red. Andy and Red aren't dual protagonists, because they don't pursue a shared goal. They're not split, because they're not on either side of a conflict. In fact, Andy is the protagonist of the film, while Red serves as a witness; something called the witness character. Red narrates the story and observes it, but it is Andy's actions, not Red's, that drive the plot. Andy's struggle is the heart of the film.

And what exactly is Andy's goal? In a sense, there are two goals—the one we think Andy is pursuing, and later, the one we discover he was secretly in pursuit of the whole time. At first, we believe Andy's goal is to maintain hope (an internal goal). However, at the story's end, we realize that Andy's goal was actually to break out of Shawshank (an external goal). But there is a strong relationship between these goals, as the tunneling probably helped Andy maintain hope, and he needed that hope to stay steadfast with the tunneling.

Even the major events defy easy analysis. The midpoint is easy enough (playing Mozart) and you can probably spot plot point 2 (Tommy's murder), but where the heck is plot point 1? Upon first viewing, in the context of Andy's goal of maintaining hope, plot point 1 seems to be when Andy offers the fearsome Captain Hadley free tax advice, garnering himself special privileges with the prison staff. But looking back with the knowledge that Andy was secretly hatching an escape plan, we realize that the seemingly innocuous moment in which Andy gets Red to agree to obtain a mini-rock hammer is, in fact, plot point 1, a giant step toward Andy's secret goal of breaking out.

Another irregularity of The Shawshank Redemption is how the climax is revealed. We don't actually see Andy's dramatic break as it occurs. Instead, we experience the discovery of the event along with Red and the antagonist, Warden Norton, when the warden sends a rock whizzing through the poster. Then we're finally shown the climactic break-out in flashback.

And get this: The Shawshank Redemption breaks the holiest of holy rules. It has four acts! As soon as Andy is free, his goal is achieved, but the movie is far from over. It continues to track Red through his parole and release, sticking with him as he follows Andy's clues to join him on the beach in Mexico. In a sense, this is a sort of Act IV in which, at the end of the story, Red really does take on the role of protagonist. So, there's another rule broken—the protagonist shifts.

These rules were not broken by accident; they were broken for strong dramatic reasons. In the final analysis, it's not fidelity to the "rules" that make a film great. Greatness comes when a film finds its true path.

Outlines

For your movie to work, you've got to get the structure and the plot just right. That's why most screenwriters don't just dive in, blindly typing their screenplays from page one. We plan out our stories in advance, using outlines. If a screenplay is a blueprint, think of an outline as a blueprint for the blueprint.

Each writer's process is different. I know a few screenwriters who never work with outlines. But most of us consider outlines essential. I'd estimate that fully half the work I do on a script takes place at the outline stage. Hell, I've even been known to spend more time on my outline than I do writing the screenplay itself! By starting with an outline, you are more or less trying out your ideas to assess how they might translate into a movie. Looking at your outline, you can ask yourself certain key questions. Will my story work in a three-act structure? Does the inciting incident spark the MDQ? Does the midpoint alter the playing field? Are things flowing right? Do I have a strong enough climax? If the plot isn't working right off (and it never does), it's a lot easier to experiment with it in outline form than it is in a screenplay, where you would have to rewrite a disproportionate amount of material to accommodate a single change.

An outline acts like a road map. You can refer to it as you write your screenplay to help you stay on track, to remember where you're going, and to keep your eye on the big picture of your story. For most writers, that's a lot easier than making it up as you go.

There is no right way to outline. You can scribble it on napkins, sort it out on index cards, write it in pig Latin. Whatever works. No one sees your outline but you. That said, there are three common types of outlines used by screenwriters.

Chart of major events: This is often the first outline you'll do. It's quite short, a few lines citing the five major events, the guideposts of your plot. (See page 66.)

Beat sheet: This is where you literally plot out each event, or "beat," of your story. Not just the major events, but every event. Everything that happens, in order, from start to finish. (See chapter 5 and page 174.)

Treatment: This is where you write out a prose version of your story, as long or short as you like. One page, twenty pages, it's up to you. Some writers feel this is a good way to get on the pulse of their screenplay. It can also be a great way to get your story into a readable shape in order to elicit feedback from a few trusted friends.

Here's how I do it. Invariably, I start with the outline of major events. Although it covers only five points, this is actually one of the most crucial stages of my entire process. If the major events don't do what they're supposed to, nothing I subsequently write will hold up. I sometimes spend days getting these five events in order. As soon as I'm satisfied with the major events, I move on to the beat sheet. This is one of the longest and most involved parts of my writing process. I've spent weeks at this stage, tinkering and reorganizing until I've worked out the order of events for the whole movie. Then, if I'm working with producers who need to sign off on my choices, I'll write up a treatment for them, usually around ten pages. If I'm working on a spec script, occasionally I'll write a much shorter treatment so that friends can give me feedback, but most of the time I just skip the treatment and go straight to the screenplay. (Getting to know your characters will help with all of this and that's something you'll learn about in the next chapter.)

Your outlines will guide you along your path of action. Follow them as you work. But don't feel that you must stick to them. Things change as you write. New ideas pop up, old ones fail you. Stay open to inspiration; always be on the lookout for something better. The outline is only the road map, not the journey itself. It works a lot like a real-life road trip. Before you leave, you plan your course: make it to Atlanta by six o'clock, hit Birmingham by noon the next day, New Orleans by nightfall. A solid plan, and yet who knows what a spontaneous detour might reveal? Maybe you scrap the idea of making it to New Orleans by nightfall and visit Black Bayou Lagoon, and there's a tavern there where you shoot darts with the locals, eat the best seafood gumbo you've ever tasted, then meet up with someone who turns out to be a lifelong friend. It's what you do along the path that matters most. Sometimes the best plan is to fold up the map and listen to your instincts.

Stepping-Stone: Major Dramatic Question

Work up the major dramatic question of your movie by identifying the protagonist and his or her goal. Then list as many obstacles as you can think of. Try to include both external and internal obstacles. And see if you can identify a primary obstacle. You may not use all of these obstacles, but your list will help you determine whether your story has enough potential conflict.

Then list ideas for at least five scenes that would show the protagonist in pursuit of the goal. Your scene ideas may or may not end up in your screenplay, but this will get you thinking in the right direction.