1 Embalmed Vision

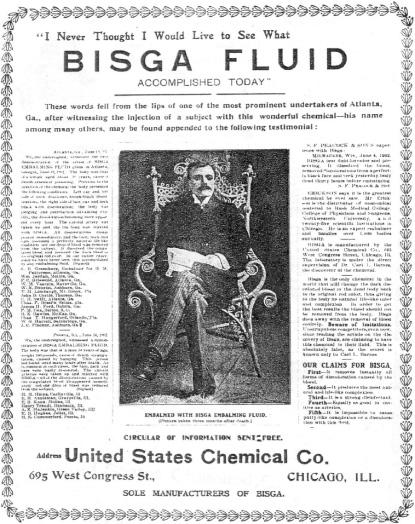

I want to say a few words to the American funeral directors and embalmers: Six months ago I made a few gallons of Bisga Embalming Fluid. ... I was finally able to produce a chemical which would not only remove the discolorations, if present, but would combine with the dark discolored blood and restore it to its natural color, thus removing every vestige of discolorations and thus give the body a perfect life-like appearance.

—Carl Lewis Barnes, Bisga Embalming Fluid advertisement, 1902

Dead bodies always attract attention, so in October 1902, Dr. Carl Lewis Barnes and his brother Thornton H. Barnes, both instructors at the Chicago College of Embalming, created a large exhibition of embalmed corpses and body parts for the National Funeral Directors Association in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The Barnes brothers’ exhibit featured human specimens preserved with Bisga Embalming Fluid—a product invented and produced by Dr. Barnes for commercial use by other embalmers. An early trade journal for professional embalmers and funeral directors, appropriately named The Casket, printed the following description of the exhibition in its December issue: “Over fifty specimens were on exhibition and the walls of the room were covered in photographs showing the apartments of the Chicago College of Embalming, special drawings of dissections of the arteries, veins and organs. ... No more striking exhibit was ever made than this one. It represented just what Bisga will do when properly used.”1

The centerpiece of the exhibit was the Bisga Man, an embalmed male corpse sitting upright in a chair, with one leg crossed over the other, and wearing a fashionable suit. According to the story in The Casket, the Bisga Man was “one of the most remarkable specimens of embalming ever produced in this country.”2 The emphatic response to the Bisga Man was a testament to how striking it was at the time to see a corpse looking so incredibly alive. In early-twentieth-century America, the Bisga Man represented the perfect nexus of mid-to-late-nineteenth-century preservation technologies that radically redefined the organic existence of the human corpse. These preservation technologies represented a series of overlapping human choices, embalming chemicals, machines, and funeral practices, all intent on keeping the dead body looking “properly human.” Yet these industrial forces acting on the human corpse did much more than suspend decomposition by altering the dead body’s chemical physiology: through these forces, the concept of human death was itself being simultaneously altered.

It was through this industrialization of the dead body in mid-nineteenth-century America that the modern human corpse also became an invented and manufactured consumer product. More specifically, the modern human corpse became (and remains) an invention of specific mid-nineteenth-century embalming and photographic technologies that seemingly stopped the general public from seeing the visible effects of death. Additional, disparate technologies for handling dead bodies, such as the availability of transcontinental railroad transport and late-nineteenth-century American funeral industry practices, also then merged to expand and control the amount of time available for handling corpses. The merging of these seemingly disparate technologies during the latter part of the nineteenth century not only produced a new understanding of death for twenty-first-century Western nations but, more importantly, they invented a timeless human corpse that resisted organic decomposition and visual degradation. In their own specific ways, each of these technologies helped invent a completely new concept of the dead body.

Postmortem Subjects and Postmortem Conditions

Given the twenty-first-century corpse’s organic stability born from nineteenth-century embalming innovations, the day-to-day (albeit largely invisible) presence of dead bodies creates a contradiction: the technologically altered dead body remains a somewhat underexamined subject.3 Various medical, political, economic, philosophical, and religious discourses include the history of the corpse, but these same discursive groups often overlook the mechanically produced, dead human body.4 The term postmortem subject most accurately defines this overlooked dead body and encompasses the social, political, and biological conditions that surround death, making the ever-malleable human corpse commodifiable.5 As such, the emergence of the postmortem body—as in a body with a “life” after life—is inextricably connected to the nineteenth-century technologies altering the human corpse.

The historical emergence of the postmortem subject can therefore be seen as the moment when preserving the corpse became a human action that made the dead body look more alive. While these technological modifications to the human corpse began in mid-nineteenth-century America, they absolutely continue today in different and often ephemeral forms.6 Indeed, the postmortem conditions, a field of dynamic relations between a human corpse and a living person, consistently illuminate the legal, medical, and biological fluctuations that help articulate both death and the dead body.7 These postmortem conditions encompass the scenarios of everyday life that legislate and attempt to define an increasingly heterogeneous concept of death for the dead body. As human definitions of death change, so too do the postmortem conditions that produce differing, at times completely oppositional, ontological states. These conditions are also a product of intense, technological changes that increasingly mediate the human body’s postmortem state. Nineteenth-century embalming and photographic technologies, for example, became important tools that destabilized and redefined the postmortem state of the corpse by creating entirely new kinds of postmortem conditions.

The human corpse is positioned in these conditions as maintaining a dual functionality as both a deceased subject and a dead object. It is important to use the categories of “deceased” and “dead” with these specific subject/object relations for two reasons. First, the deceased subject is most certainly not a dead object for consumers of medical and funeral practices, such as family members, clergy, and so on. Second, the dead object is not necessarily a deceased subject for users of medical and funeral technologies. This proposed subject/object relation is arguably not a cleanly defined separation where either can be easily located. The ontology of each depends, then, on the observer’s relation to the corpse within the fluctuating thresholds of the postmortem conditions. Examining the postmortem conditions produced by nineteenth-century technological changes to the dead body requires using a three-part structure that is both historical and theoretical: the relationship between photography and embalming, postmortem circulation and fluidity, and the construction of a paradoxically “alive but dead” modern, hyperstimulated corpse.

Photography and Embalming8

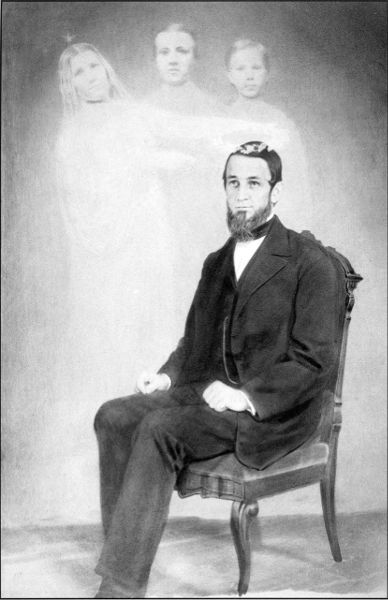

Tom Gunning argues that nineteenth-century American photography allowed the mechanical reproduction of the three-dimensional world and produced “the standardization of imagery” for industrial societies.9 As the imagery of human life became recorded, printed, and reproduced, so too did human death. Remembering a dead person through photographic evidence of the deceased body emerged as one of the key uses of this new form of visual reproduction.10 The photographic record of what a dead body looked like began the important process of standardizing how postmortem conditions could or should appear when viewed by the living. To illustrate how popular death photography became in this era, Gunning discusses the production of so-called “spirit photographs” in mid-to-late-nineteenth-century America and Europe. The spirit photographs captured photographic images of a deceased person’s soul “miraculously” appearing in the background of family portraits (see figure 1.1). The spirit in the photograph was not limited to family members since “images of Lincoln and Beethoven” sometimes also appeared standing behind the living person being photographed.11

Figure 1.1

Spirit Photograph, Man and His Departed Family. Source: Courtesy of Stanley B. Burns, MD, and the Burns Archive. (From Sleeping Beauty II: Grief, Bereavement and the Family in Memorial Photography, Burns Archive Press, 2002, p. 52.)

In Gunning’s analysis of popular nineteenth-century attitudes about photography, he argues that the public believed that the machinery of the camera could somehow “see” the world of death in ways regular human vision could not. Gunning explains how and why nineteenth-century photography consumers came to believe in the seemingly impossible appearance of a “spirit”: “... ghosts invisible to the human eye are nonetheless picked up by the more sensitive capacity of the photograph.”12 Of course these spirit photographs were doctored images, where the photographer had superimposed the “ghost” of the deceased person into the image at a later time.13 The public acceptance of the spirit photographs suggests, however, that the power of the machinery producing the images could really capture the “true” appearance of death as it affected the living. Spirit photography did not itself become the main form of mourning photography, but the ability to photograph a deceased person turned human death into a stable, temporally fixed image, capturing a body unchanged by organic decomposition. As Jay Ruby explains in Secure the Shadow, his book on the history of death photography: “Photographs commemorating death can be seen as one example of the myriad artifacts humans have created and used in the accommodation of death. Because the object created, i.e., the photograph, resembles the person lost through death, it serves as a substitute and a reminder of the loss for the individual mourner and for society.”14

As the postmortem photograph came to define the appearance of the dead body for years to come, the era’s photographers strove to capture the most vital image possible. Photographs of the corpse were quickly taken to prevent signs of decomposition from appearing in the image and to capture the deceased person looking as “alive” as possible. “During the first 40 years of photography (ca. 1840–1880),” Ruby explains, “professional photographers regularly advertised that they would take ‘likenesses of deceased persons.’ Advertisements stating that ‘We are prepared to take pictures of a deceased person on one hour’s notice’ were commonplace throughout the United States.”15 The rapid availability of both photographers and photographs meant that the postmortem state of a dead body could be fixed into a reproducible image far faster and with less expense than, for example, death portraits painted on canvas a century earlier.16

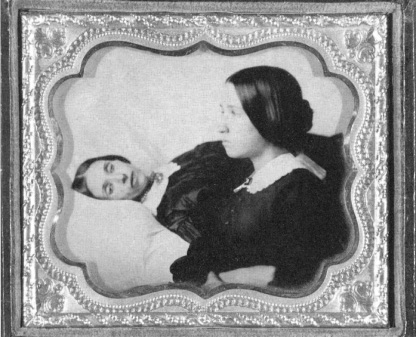

Ruby goes on to explain that “[t]he custom of photographing corpses, funerals, and mourners is as old as photography itself. It was and is a widespread practice and can be found in all parts of the United States among most social classes and many ethnic groups.”17 The freezing of the corpse’s image, “the fascination with death and its overcoming through the technical device of mechanical reproduction,”18 produced a visual index of how death appeared for many Americans during the nineteenth century (see figures 1.2–1.4). A dead person’s image could now become a corpse from anywhere at any time, no longer limiting the visual consumption of human death to immediate family. Individual human memories of a dead person’s body, in the era before photography, were often confounded by that same body’s inevitable state of decomposition, meaning that viewing the corpse needed to occur before it began breaking down.19

Through photography, large numbers of people beyond immediate family members could look at a lifelike representation of the dead body indefinitely and in any location the image traveled. As a mechanical apparatus, the camera effectively removed the dead body from any time and space constraints created by death. Images of death suddenly became mobile visual accounts of what a person looked like at the time of burial. The human corpse was also the perfect subject for early photography since it lacked any bodily movement. Southworth and Hawes, a prominent mid-nineteenth-century Boston daguerreotype and photography studio, ran the following advertisement playing on these same public fantasies about vital-looking dead bodies: “We take great pains to have Miniatures of Deceased Persons [wallet or postcard size images] agreeable and satisfactory, and they are often so natural as to seem, even to Artists, in a deep sleep.”20 The visual index mechanically produced by photographers created a profoundly new way of seeing the dead body for the general public. A letter written in 1870 from Eva Putham to her Aunt Adelaide Dickinson Cleveland describes the photograph taken of Adelaide’s dead sister Mabel and offers a vivid example of how strong the mechanical-visual control of the corpse had become: “How lonely you must be, how could you endure it. If it were not for the assurance that it’s all for the best. I am glad that you could get so good a picture of the little darling dead Mabel as you did, the fore head and hair look so natural.”21 By the late 1800s, advertising about postmortem photographic services began to disappear from both general circulation periodicals and photography journals since public knowledge of death photographs had become widespread.22

Figure 1.2

Postmortem photograph of unidentified woman. Source: Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum (2019). (From Secure the Shadow, MIT Press, 1995, p. 68.)

Figure 1.3

Postmortem photograph of mother with dead child. Source: Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum (2019). (From Secure the Shadow, MIT Press, 1995, p. 91.)

Figure 1.4

Postmortem photograph of mourner with dead woman. Source: Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum (2019). (From Secure the Shadow, MIT Press, 1995, p. 95.)

Death photography continued unabated until another nineteenth-century technological innovation altered postmortem conditions for human bodies. The new technology was mechanical embalming, and it slowly but surely became a normalized postmortem practice in the United States after the Civil War.23 Robert Habenstein and William Lamers explain in The History of American Funeral Directing that the Civil War was “the first conflict to see embalmers waiting and working in camps, on battlefields, in government hospitals, and in nearby railroad centers, to serve the needs of the military and the families of the fallen.”24 After the Civil War ended in 1865, the practice of embalming had become so widespread for Union Army soldiers killed during battle that embalmers had a new consumer product to offer the general public: the mechanically preserved dead body.25 The photographic images of dead persons offered by firms such as Southworth and Hawes defined and standardized a history of postmortem visual culture that played an integral part in the production of lifelike corpses for late-nineteenth-century embalmers. The use of photography did not completely disappear from the early-twentieth-century funeral industry; rather, embalming allowed the actual body to be on display without the requirement of a fast burial. Instead of eliminating postmortem photography, embalmers simply copied the photographic image’s aesthetic (to produce the effect of “deep sleep”) for the dead body.

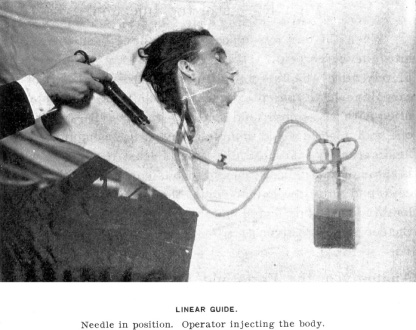

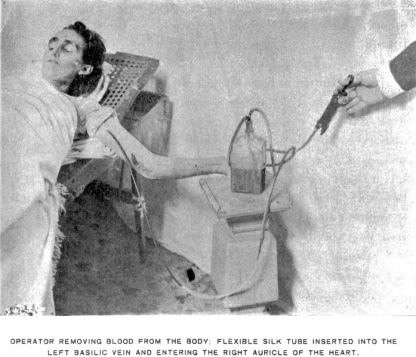

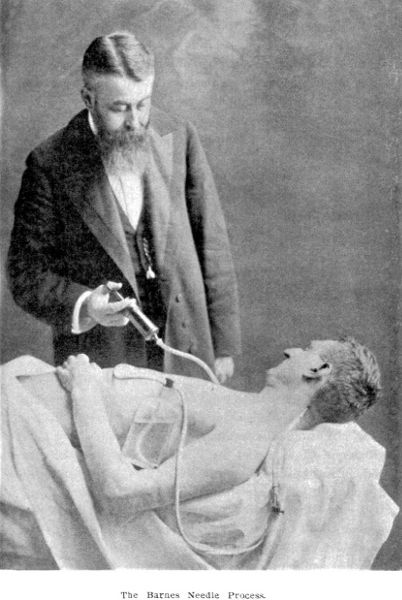

The nineteenth-century embalming process involved removing the bodily fluids of a corpse through a handheld vacuum pump. Once the organic fluids were removed, the pump was used to reinject the dead body with a preservative chemical solution (see figures 1.5–1.8). Mechanical embalming’s fundamental historical importance was that it marked the radical slowing of decomposition by overriding the human body’s biology. This mechanical-chemical process ultimately produced a dead body that remained unaltered by time.

Figure 1.5

Embalmer injecting the corpse with fluid. Source: Courtesy of the National Funeral Directors Association (USA). (From The Art and Science of Embalming, Trade Periodical Company, 1896, p. 248.)

The embalming process produced rather “amazing” effects, as an advertisement from an 1863 Washington, DC, business directory proclaimed:

- Bodies Embalmed by Us

- NEVER TURN BLACK!

- But retain their natural color and appearance; indeed, the method having the power of preserving bodies, with all their parts, both internal and external.

Figure 1.6

Embalmer removing blood from corpse. Source: Courtesy of the National Funeral Directors Association (USA). (From The Art and Science of Embalming, Trade Periodical Company, 1896, p. 141.)

- WITHOUT ANY MUTILATION OR EXTRACTION,

- and so as to admit of contemplation of the person Embalmed, with the countenance of one asleep.26

The Art and Science of Embalming (1896), a nineteenth-century textbook written by Dr. Carl Lewis Barnes, goes to great lengths to explain the power represented by properly embalmed bodies. Barnes provided four key reasons for embalming the dead body: [1] “to prevent the appearance of putrefaction until such time that the body may be viewed by the friends of the deceased, or until it can be conveyed to a suitable resting place ... [2] that of disinfecting the body ... [3] preservation of a body until it may be identified. ... [4] A fanciful reason for embalming is that the body is made to look life-like.”27 Barnes clearly explains, point by point, that the power of embalming is total control of the dead body, to prevent any kind of disease or organic breakdown and to maintain the body’s aesthetic appeal. Later, in the same textbook, Barnes likens the work of the embalmer to assisting the work of God: “EMBALMING prevents the corruption of the grave, so that the body will remain entire, and as it were asleep in its bed, till awakened by the last trumpet to a joyful resurrection, where in its flesh it shall see God. ... Hereby death has no more power over us than a long sleep.”28

Figure 1.7

Embalmer injecting fluid into corpse. Source: Courtesy of the National Funeral Directors Association (USA). (From The Art and Science of Embalming, Trade Periodical Company, 1896, p. 231.)

Figure 1.8

Embalmer using the Barnes embalming method. Source: Courtesy of the National Funeral Directors Association (USA). (From The Art and Science of Embalming, Trade Periodical Company, 1896, p. 251.)

The connections that Barnes makes between the total control of the dead body and the Providential virtues of the embalmer’s work are significant for both the postmortem condition and visual control of the dead body.29 Embalming, in a way similar to death photography, affected not only how the viewer observed the corpse’s postmortem state but also radically altered the process of gazing at a dead body. This is the crucially important meeting point of photography and embalming: What embalming and death photography fundamentally changed was how the living observer viewed the postmortem conditions of the corpse. In effect, these innovations in embalming practices enabled the emergence of embalmed vision. Visually experiencing the corpse for an extended period of time no longer required photographic lenses, since the public could now see the dead body by using the pumps and needles of the Barnes embalming method. This crucial shift for the nascent American funeral industry standardized an experience of the corpse that persists today, and it altered the popular understanding of how “natural” or “normal” death appeared. In his history of death in America, James Farrell cites two examples of this early visual control over the dead body: “W.P. Hohenschuh [an Iowa funeral director] advised that ‘one idea should always be kept in mind, and that is to lay out the body so that there will be as little suggestion of death as possible.’” A few years later in 1920, “a Boston undertaker allegedly advertised: For composing features, $1. For giving the features a look of quiet resignation, $2. For giving the features the appearance of Christian hope and contentment, $5.”30

As the prices listed by the funeral director in Boston suggest, the embalming process and the embalmed vision it produced meant that the corpse could now be commodified in new ways. Since the tools used to alter the corpse were largely invisible and the embalming process took place behind closed doors, the end result was a new kind of postmortem subject that looked alive, yet bore no visible marks of mechanical intervention. The embalming tools’ sheer invisibility meant that the mechanical apparatus could itself become permanently attached to a viewer’s understanding of the dead body, without directly altering the observer’s conscious understanding of death. Almost imperceptibly, the act of looking at a corpse in the late nineteenth century shifted from potentially seeing uncontrolled decay to seeing a mediated image of the dead body. As the previously unregulated postmortem conditions of the dead body came under control, first through photography and later through embalming, the living observer’s embalmed vision effectively cocooned the corpse. The dead body was placed in a space of death stripped of any adverse smells, appearances, diseases, or even human mortality itself. The corpse was no longer controlled by biological death in the late nineteenth century; rather, control of the corpse and the “death” that it presented shifted to human actors.

As soon as the dead body began to look less dead, the need to reproduce and consistently reaffirm embalmed vision (over time and across geographical boundaries) created an entirely new market for handling human corpses. The relationship between photography and embalming took the decomposition of corpses and turned it into an economically profitable business. While the embalming process helped transform the human corpse into a new consumer product, it also served to eliminate the perceived public health disease threats associated with circulating the dead in the public sphere by making the deceased body “safer.” Embalming’s hygienic popularity resulted in the growth and marketing of many fluid-based, preservative disinfectants, but it also led to a number of problems for both the emerging early-twentieth-century funeral industry and for dead bodies.

The Politics of Circulation and Fluidity

The terms circulation and fluidity have dual meanings for the technologically altered human corpse, but both sets of meanings represent important aspects of what happened to dead bodies, in America, during the nineteenth century. Circulation and fluidity are used here to mean both the movement of fluids through the human body and the railway shipment of dead bodies circulating across the United States. The use of these terms is partially rhetorical, but more accurately material. Each term serves as a means to articulate how the nineteenth-century human corpse became the nexus for controlling both the temporality of death via embalming and the space of death with train travel. Shipping the dead body on trains added yet another important level of human technological control over the dead body.

The history of how dead bodies could be made safe for transcontinental travel in America is a story closely tied to the mergers of chemical embalming and the emergence of city-to-city rail transit. The American population’s expansion across the continent meant that corpses needed to travel the same distances and routes. Farrell comments, “During the Civil War, some people embalmed bodies for shipment home from the front. After the war, embalmers continued to prepare the bodies of formerly mobile Americans for shipment to family and friends.”31 Habenstein and Lamers highlight the multiple issues encountered when shipping dead bodies during the post–Civil War nineteenth century, noting that “it became necessary to inspect trains at depots for improperly embalmed bodies, broken shipping cases, bodies bearing the germs of infectious diseases and the like.”32 They go on to explain how “exasperated” funeral directors from across the country often described “the chaos of uncodified and non-articulatory rules and regulations dealing with this problem.”33

Funeral directors and train companies that shipped bodies, both immediately following the Civil War and into the early twentieth century, faced a serious situation: the propensity for substandard embalming jobs done by poorly trained embalmers. In October 1907, the 4th Annual Joint Conference of the Embalmers’ Examining Board of North America convened in Norfolk, Virginia, to discuss the problems arising from inadequately embalmed bodies being shipped across the United States. The Embalmers’ Examining Board of North America’s president, Dr. H. M. Bracken of St. Paul, Minnesota, delivered the conference’s annual address and explained the need for individuals preparing the dead for transport to receive a more thorough and standardized embalming education: “So long as the undertaker was interested only in preparing the remains of the dead for immediate and local burial he had a simple task before him. But with the age of travel and migration a new responsibility was thrust upon him, viz.: the preservation of a body in order to permit of its shipment. This responsibility changed the undertaker to the embalmer.”34 Training individuals in how to properly embalm dead bodies for rail shipment, however, also created opportunities for unscrupulous con men. Bracken explains, “As the quiz master came into existence to prepare the medical student for his examination, so the ‘fluid Man’ sprang up to provide embalming fluids and embalmers’ quiz classes for the embalmer.”35

Bracken’s description of the “fluid Man” was a term used to describe individuals who worked as itinerant embalming educators, opening “schools” across the country to teach would-be embalmers how to preserve dead bodies. The instructors were themselves mostly unqualified to teach embalming, and their work often yielded dubious results.36 Habenstein and Lamers comment: “It is interesting also to note that the earliest compounders of embalming fluids, whether medically trained or not, chose to call themselves ‘professors... .’ Thus a good decade before the appearance of any type of formal instruction, ‘Professor’ E. Crane had patented in 1868 and sold ‘Crane’s Electro-Dynamic Mummifier.’”37

In 1906, a year before Bracken’s address, the professionals most affected by the work of the “fluid Man” had already convened a special meeting to establish and standardize railway transport rules for the dead body.38 The meeting’s main participants included the National General Baggage Agents’ Association, the National Conference of Health Officers, and the National Funeral Directors Association. The “Transportation Rules” approved at the meeting stipulated a series of nine, self-imposed regulatory mandates that directly addressed the problems created by bodies improperly prepared for shipment.39 The rules covered an array of diseases (yellow fever, anthrax, etc.) as well as how the dead body should be shipped.

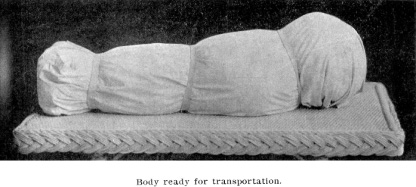

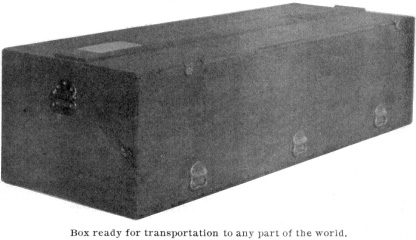

Rule 1 was the most explicit: “The transportation of bodies dead of small pox and bubonic plague, from one state, territory, district or province to another, is absolutely forbidden.” Rule 2 required a state-certified embalmer to properly prepare any dead body exposed to disease by embalming it, disinfecting it, and putting “absorbent cotton” in any orifice. After completing those procedures, “such bodies shall be enveloped in a layer of dry cotton not less than one inch thick [see figure 1.9], completely wrapped in a sheet securely fastened and encased in an air-tight zinc, copper or lead lined coffin, or iron casket, all joints and seams hermetically sealed, and all enclosed in a strong, tight wooden box” [see figure 1.10]. After the corpse was properly prepared for shipment, Rule 6 required that “every dead body must be accompanied by a person in charge, who must be provided with a passage ticket and also present a full first-class ticket marked ‘corpse.’”40 The full nine transportation rules cover a variety of other logistical issues, including guidelines for the dead body’s “express transit.” Guaranteeing the safe passage and proper delivery of a dead body meant creating a whole new regulatory regime for the emerging nineteenth-century transportation industry. Mechanical embalming was a crucial part of that new regime since it enabled chemical control over the dead body’s circulation and fluidity.

Figure 1.9

Corpse wrapped for train transport. Source: Courtesy of the National Funeral Directors Association (USA). (From The Art and Science of Embalming, Trade Periodical Company, 1896, p. 349.)

Figure 1.10

Corpse shipping casket. Source: Courtesy of the National Funeral Directors Association (USA). (From The Art and Science of Embalming, Trade Periodical Company, 1896, p. 350.)

In addition to possessing a first-class railway ticket, an embalmed corpse could now also circulate outside conventional time and space through these same preservation methods and transport systems. As a general rule, the space and time occupied by living bodies and dead bodies functioned differently. Yet with the advent of nineteenth-century embalming technologies, the living could usurp this temporally adjusted corpse time and make dead bodies conform to rules not within the human gene code, that is, the automatic postmortem onset of organic decomposition.41 Wolfgang Schivelbusch most accurately describes these kinds of temporal changes in The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century. While Schivelbusch does not directly address train travel’s effects on dead bodies, his overall analysis of how a radically altered time code affected the circulation of living bodies absolutely includes the human corpse. Schivelbusch argues: “‘Annihilation of space and time’ was the early nineteenth century characterization of the effect of railroad travel. The concept was based on the speed the new means of transport was able to achieve. ... In terms of transport economics, this meant a shrinking of space.”42

The unembalmed dead body resisted this new temporal annihilation better than many other human bodies at the time. This meant that the total preservation of the human corpse became a necessity in order to make the dead body controllable for both train travel and transport economics. The shipping problems encountered by funeral directors, baggage workers, and state health officials help illustrate Schivelbusch’s additional point that “the alteration of spatial relationships by the speed of the railway train was not simply a process that diminished space, but that it was a dual one: space was both diminished and expanded.”43 By the early twentieth century, regulated embalming similarly diminished decomposition and made expanded travel by most dead bodies possible—setting aside cases of infectious disease such as bubonic plague. The enlarged distance required to transport a dead body no longer posed a problem since the entire concept of corpse time and cadaveric decomposition had largely been slowed.

Two very different kinds of nineteenth-century machines, embalming tools and trains, subsequently merged to exert control over the human corpse. This industrialized control of the dead body meant that embalmed vision could function without concern for the space and time of death. Once embalming slowed conventional time from affecting the dead, the organic space of death became replaced by something new for the modern corpse—a mechanically produced space of ontology. The control exerted over the human corpse in the nineteenth century also meant that American funeral directors suddenly acquired a great deal more power as both licensed embalmers and producers of the dead body’s final appearance. Just as properly embalmed bodies helped the railway companies move corpses across state lines, the transportation rules also helped funeral directors further legitimate their work. Habenstein and Lamers explain the long-term benefits of the new shipping regulations for funeral directors: “Finally, they gained professional recognition for their work in embalming; that is, the affidavit of a funeral director that he had embalmed a body was accepted at face value henceforth by baggage agents and public health functionaries alike.”44 Early-nineteenth-century postmortem conditions and corpse time were spaces initially outside concrete human control, but control was finally exerted as new technological methods normalized the “healthy” looking dead body. What the dead body’s circulation and fluidity on trains quietly created for American funeral directors was the total consumption of postmortem space and time.

Construction of the Modern, Hyperstimulated Corpse

The unveiling of the Bisga Man by Dr. Carl Lewis Barnes in 1902 marks a particularly historic moment for the modern corpse.45 The Bisga Man’s creation introduced a highly compelling paradox: the invention and marketing of the ultramodern and hyperstimulated human corpse (see figure 1.11).46 Barnes used the Bisga Man to literally and figuratively embody the catalog of changes made possible by nineteenth-century preservation technologies. The Bisga Man was also the perfect human model for the most powerful promise made by nineteenth-century embalming and preservation: dead bodies could suddenly appear unnaturally alive.

Figure 1.11

Bisga Fluid advertisement featuring the Bisga Man. Source: Courtesy of the National Funeral Directors Association (USA). (From The Sunnyside, 1902, National Funeral Directors Association archive.)

From the Civil War era onward, the ontology of the corpse becomes a highly productive relationship for living and dead bodies alike, and represents not a reversal but rather an extension of the space occupied by the dead body. The Bisga Man is an example of a corpse living within that new postmortem ontological structure, demonstrating how postmortem conditions also impinged upon the existential questions raised by mechanically altering dead bodies. The photograph used in the Bisga embalming fluid advertisement is an illustration of a human corpse doubly altered by nineteenth-century preservation machines: first by embalming and then by photography. In a break from nineteenth-century death photography norms, the Bisga Man’s image was not a postmortem reminder of the deceased person. Instead, his entire existence as a marketing tool was made possible by merging the power of photography and embalming. The caption underneath the Bisga Man photograph encapsulates that new power by simply stating “Picture taken three months after death.” Another version of the advertisement testified that Bisga Fluid produced a “perfect life-like appearance.”47 The amount of time that had elapsed since the Bisga Man’s death was crucial in demonstrating to other embalming practitioners just how alive they could make their own dead bodies look if they opted to technologically control the visual experience of human death.48

Barnes’s advertisement is especially compelling since it manipulated the postmortem conditions of embalmed vision in a counterintuitive way: without the caption describing the Bisga Man as “after death,” the body actually looked alive. The Bisga Man exists as a modern corpse whose life and death is impossible to recognize or decipher without the assistance of the caption. Death, as represented by the Bisga Man’s postmortem vitality, is reduced, on the one hand, to a textual prompt and is expanded by Barnes, on the other, into a marketing strategy. The alive-looking dead body’s technical production through mechanical means, and the subsequent suspension of death from the corpse, meant that modern technologists had found a way to make human death mechanically disappear. From the early-twentieth-century viewpoint of embalmers and funeral industry workers, this new kind of corpse was an object of vast capital potential that simultaneously remained a subject of loss for mourners. With the emergence of machine-based embalming systems, and to a certain extent photography, the modern corpse could suddenly function longer and be more profitable for all living parties. Dead bodies that resist decomposition are perfect candidates for a whole range of postmortem applications, and these conditions make death highly profitable for the industries turning the dead body into an unfettered source of capital.

Death and the dead body in America were radically altered by nineteenth-century technological control over the corpse’s inner chemistry and outer appearance. The modern corpse’s invention was a product of various invisible human machines, infiltrating and hyperstimulating the dead body for the multiple and varied purposes of the living. What made the development and use of embalming so important was the absolute invisibility through which it functioned. The process of embalming was hidden from view, as were the chemicals used by embalmers. What emerged from nineteenth-century mechanical labor on the human corpse was a modern dead body that required embalmed vision to be seen in the proper context and state of vitality. The corpse that emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries persists today in its capacity to remain both lifelike and visible. If left unmediated, the dead body is a shocking spectacle for those not accustomed to seeing physical decomposition. Death photography, mechanical embalming, the dual meanings of fluidity and circulation for dead bodies, and the invention of modern corpse ontology were all used to produce late-nineteenth-century postmortem conditions. Most significantly, they each served to condition a dead body that would undergo further, radical changes in the years to come.

7/29/2018

Watching My Sister Die—#21. Julie Post

I’m on the plane right now

little sister

Flying to you and your dead body

You died 30 minutes ago

Your body finally gave up after you pushed so far.

I said goodbye but I still wanted to be there

today

when you died.

If only you could have waited five-more hours ...

But I know you waited long enough

None of this was supposed to happen this way.

You were never supposed to die first.

But you did.

And tonight when I hold your hand I’ll tell you about

all the things people said about you

our friends

After I finally crossed 21. Julie Post off my to do List.

After I held your hand and told you that you were dying.

through tears and tears and you telling me → I’d do the same for you.

And you would. I know it.

It’s so beautiful up here, little sister.

10,000 feet above the world

Pale Blue skies and remnants of clouds drifting past the

British landscape you always enjoyed.

Laughing about how my job never really made sense

that only your marching to a different beat brother could

end up as the Overlord of Death

But here’s the thing, little sister.

This impossible career only really made sense to me 30 minutes ago

when you died

When I held your hand telling you that you were dying.

When Death warned me that I wasn’t prepared for this moment.

Oh little sister—I never wanted to be an only child

you were the one who was supposed to care for Mom and Dad

And now it’s all on me, in these final years.

The beginning of one less person in these family photographs.

It doesn’t seem possible. All of this. Happening Now. But it is.

The Death Family is not protected or immune from mortal ends.

I’ll be with you soon and hold your lifeless hand, so full of love

for everyone around you

And so missed now by the same people.

Gate 11. Bristol Airport. A phone call from our mutual college friend.

This is how I learned you died.

So no more watching you die, little sister.

No more pain.

Just sadness and tears and the knowledge that if our roles were

reversed.

You would write these same exact words for me.