3 The HIV/AIDS Corpse

No group of professionals are more aware than funeral directors that Americans are dying prematurely of HIV and AIDS related illnesses. Not only have they had to learn how to help survivors cope with their grief, but they have had to deal first-hand with the inherent risks in dealing with possible contagious remains.

—from America Living with AIDS by the National Commission on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, The Director, January 1992

A New Postmortem Situation: The HIV/AIDS Corpse

In the twentieth century’s waning years, the supposedly stabilized human corpse took a sudden turn, and in June 1985, the National Funeral Directors Association1 (NFDA) circulated a memorandum to its affiliated members that detailed “AIDS Precautions for Funeral Service Personnel and Others.” The single page document, marked “IMPORTANT” across the top of the page, attempted to answer common questions from members of the funeral industry regarding dead bodies produced by HIV/AIDS. The opening paragraph of the memorandum provided the following statement: “There has been much publicity given AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome). This disease has led to a number of deaths with more expected. According to numerous reports, those most likely to be infected are homosexuals and intravenous drug users.”2

Since the funeral industry is one founded upon the handling of corpses, the lack of understanding about HIV/AIDS in America at that time meant that the industry’s fiscal reliance on dead bodies had suddenly become significantly more complex. The memorandum went on to state, “The growing publicity these cases are getting have some funeral directors asking for advice not only as to embalmers, but also others involved in the care and transportation of an infected body prior to and after embalming. And, what if the survivors want a funeral with a body present but do not want the body embalmed?”3

In response to this question, the NFDA suggested eight “embalming precautions” developed by the director of pathology at New York City’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the Queens Medical Examiner’s Office.4 The eight precautionary steps listed what kinds of protective gear the embalmer should wear (goggles, shoe covers, double rubber gloves, etc.) as well as the kind of bleach solution required to clean dirtied instruments. The most historically telling point in the memorandum is the eighth and final precaution on the list: “If the body is being viewed, the family should avoid having physical contact with it.” That families should avoid touching the HIV/AIDS corpse is indicative of the broader biomedical confusion and uncertainty caused by AIDS during the 1980s.5 While the memorandum does not explicitly state why funeral directors should prevent families from touching HIV/AIDS bodies, the implicit suggestion was clear—the body killed by HIV/AIDS was, at that time, a biologically dangerous corpse.6 What the memorandum also makes clear is that HIV/AIDS produced a new kind of dead body during the early 1980s—a human corpse created through a largely misunderstood disease, and, according to the logic of the memo, by the socially abject activities of intravenous drug users and homosexuals.

Yet, the HIV/AIDS corpse was more than just a dead body with socially deviant, abject qualities. This new kind of corpse became both a product of American cultural politics and a direct challenge to the nineteenth-century technologies created to standardize the modern human corpse. As the NFDA memorandum suggests, this new kind of corpse was challenging the transformative powers of mechanical embalming that purported to technologically stabilize all dead bodies. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, the power of mechanical embalming was that it stopped the dead body from rapid decay and transformed the corpse into a more stable, publicly viewable kind of body; the HIV/AIDS corpse undermined the biomedical power of that practice. In a very short series of steps, the HIV/AIDS corpse quickly became the epicenter of a supposedly socially deviant disease, and it marked the sudden impossibility of postmortem rehabilitation through proper embalming by the American funeral industry.

Examining the HIV/AIDS corpse’s social and political productivity within the American funeral industry during the 1980s and early 1990s is revealing. This is not a polemic against the American funeral industry; rather it is important to examine how this particular group of professionals made sense of HIV/AIDS through some serious industry-wide challenges. Moreover, the larger institutional changes experienced by the American funeral service industry, resulting from the emergence of the HIV/AIDS corpse, were substantial. A former University of Minnesota Program of Mortuary Science7 embalming instructor, Jody LaCourt, reflected on that historical moment: “In the early nineties, which is when I began my funeral profession, I was witness to funeral directors who ‘freaked out’ knowing they had to embalm a body that was HIV positive or died from AIDS, and some funeral directors would go so far as to refuse to embalm that body. They did not want anything to do with an HIV/AIDS body. These attitudes were extremely disconcerting.”8

The hard-line refusal of some funeral directors to embalm HIV/AIDS corpses became such a concern in the mid-1980s that the National Funeral Directors Association Board of Governors made the following policy statement on June 23, 1985:

We know that some funeral directors and certain funeral service establishments in the U.S. are refusing AIDS cases. Some firms allegedly will not embalm the bodies of AIDS victims. In some cases, firms which will serve the families of AIDS families will do so only if the body is cremated immediately and only if no viewing and/or visitation are permitted. All of this is true even though these actions may directly contradict the profession’s previously stated views on the importance of embalming. So strong is the fear of AIDS that many in funeral service apparently are not concerned that this “trend of refusal” may impair the professional image of the American funeral director. ... If this trend of refusal continues, especially with the help of those in funeral service, we could be encouraging higher rates of direct disposition9 [of the corpse]. After all, what about deaths due to other highly contagious diseases? Don’t they also pose a risk? If we encourage direct disposition for AIDS victims, shouldn’t we encourage it for others as well? If direct disposition is aided and abetted by funeral directors, there will be little incentive for the public to accept and encourage those in funeral service who support the value of funeralization.10

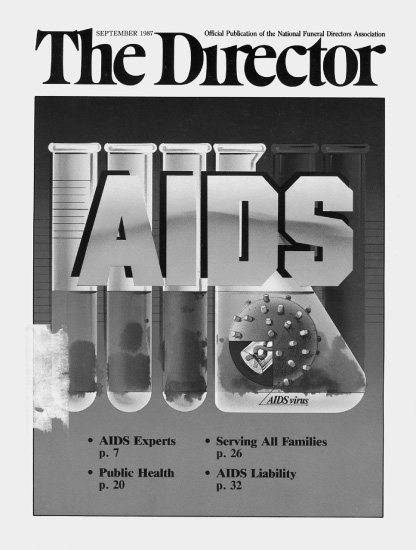

One of the funeral industry’s central HIV/AIDS information resources during the 1980s and 1990s was The Director—the monthly publication of the National Funeral Directors Association. The Director has been regularly published since 1957 and remains in print today. Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, The Director published a series of articles and commentaries on HIV/AIDS and its implications for the American funeral industry. The September 1987 issue of The Director was a particularly important publication on this score; it was the first time that an entire issue wholly focused on HIV/AIDS in American funeral practice. The issue’s cover (see figure 3.1) was a visual testimonial to how the epidemic functioned at that time within the industry. Test tubes containing various kinds of fluids float across the cover, and an asymmetrical Erlenmeyer flask holds a multipronged orb (which bears an uncanny resemblance to a World War II Naval mine). The orb itself encapsulates a container of DNA, so the double helix suggests, and in the event the reader is unsure what the multipronged orb might be, the caption “AIDS virus” appears inside the bottom of the flask. American funeral directors were engaged in “Total War,” to borrow a key HIV/AIDS metaphor from Catherine Waldby.11 The articles within the September 1987 issue, listed by category underneath the cover image (“AIDS Experts,” “Serving All Families,” “AIDS Liability,” etc.), also convey the scope of funeral directors’ concerns at that time. Lastly, the cover’s front and center positioning of the word “AIDS” leaves no doubt about either the urgency or severity of the situation confronted by the funeral industry.

The September 1987 issue begins with a new kind of old problem for American funeral directors. When dead bodies produced by complications from HIV/AIDS began showing up in funeral homes, the “threat” of viral contamination was, in theory, another part of the job. Infectious diseases of all kinds routinely produced hazardous dead bodies, and those corpses forced the funeral industry to adjust its practices. Professional embalmer and embalming science historian Robert Mayer argues in Embalming: History, Theory and Practice as follows: “Deadly flu, polio, AIDS, tuberculosis, and drug-resistant strains of virus, and bacteria have all challenged the embalmer to practice sanitary techniques to protect personal and community health. In spite of these diseases the embalmer continues to practice a skill that allows one last comforting look on the face of loved ones at their ceremony of farewell.”12 Yet for all the other historical examples Mayer cites wherein infectious disease produced dead bodies that required special attention, HIV/AIDS proved to be a very different kind of epidemiological threat. Not only was HIV/AIDS historically different for the funeral industry in terms of the populations it initially infected, so too was the industry’s confusion surrounding what to do with the seemingly contagious human remains.

Figure 3.1

The Director September 1987 cover. Source: Courtesy of the National Funeral Directors Association.

In June 1986, one year before the special issue on HIV/AIDS, the NFDA ran a nine-page article in The Director, entitled “AIDS—All the Questions All the Answers.” The article’s final question is a telling example of the confusion HIV/AIDS was creating for both funeral homes and the people trying to arrange funerals for loved ones:

- [Question] 86. Can funeral directors in New York State refuse to embalm victims of AIDS?

- Response: There is no New York State law that can require a funeral director to accept an AIDS victim. Embalming also is not required by law. The state has provided AIDS safety guidelines to funeral directors and embalmers. While some funeral establishments have refused to accept AIDS victims, there are sufficient firms available who will do so.13

And yet, as the NFDA Board of Governors asserted, the institutional history and future livelihood of American funeral directing required equal access to postmortem services for all dead bodies. As Clarence Strub and L. G. Frederick argue in The Principles and Practice of Embalming (1989): “In time of epidemic or catastrophe, it is our professional obligation to serve and to protect; no matter what our professional jeopardy may be. An embalmer cannot refuse his professional services to a family and ultimately society, just because the deceased died of some communicable disease, such as A.I.D.S.”14

HIV/AIDS was, however, different, and the bodies produced by it were both the Same and terrifyingly exotic. Paul Rabinow, in Essays on the Anthropology of Reason, builds upon Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things by suggesting that “we need to anthropologize the West: show how exotic its constitution of reality has been; emphasize those domains most taken for granted as universal.”15 And the emergence of the HIV/AIDS corpse did just that; it destabilized notions of universal death, i.e., that in death American dead bodies were mostly the same. The American HIV/AIDS corpse was actually made doubly problematic by its exotic “Otherness” which was explicitly local and domestic. While American funeral practices had been historically quasi-homogenous (different religious rituals being the key exceptions), the emergence of HIV/AIDS produced whole new sets of postmortem rules and regulations that institutionalized extreme forms of homogeneity. The universalization only occurred, however, after the heterogeneous HIV/AIDS corpse disrupted most concepts of a normal, dead body.

Technologies of the HIV/AIDS Corpse

In an article written for the September 1987 issue of The Director, Robert Mayer summarized the effects of HIV/AIDS on the American funeral industry. His article, titled “Offering a Traditional Funeral to All Families,” is a compendium of public health updates, new health code regulations, and suggested changes to embalming procedures. Mayer opens the article by commenting on the pervasive sweep of the virus across the country: “In looking at AIDS from the standpoint of funeral service, we begin to realize that the disease has spread far enough through our population that funeral homes throughout the entire United States are being asked to provide service for families who have had a relative die from this deadly killer.”16 The article proceeds to present the responses of several unnamed funeral directors when asked how they would handle the preparation of the body if presented with an HIV/AIDS corpse: “One funeral director stated he would have to charge $15,000 to handle an AIDS funeral because the entire preparation room would have to be refurbished. Another funeral director said he considered an AIDS victim to be the same as a highly radioactive body. ... In fact, he stated he would not even accept a call from a family whose relative had died of AIDS.”17 And while there was certainly a shared anti-AIDS corpse sentiment circulating within the industry, it is important to note that other industry members agreed to embalm HIV/AIDS corpses without such overt hesitancies.18

That said, the unnamed funeral director’s analogy in Mayer’s article between the “AIDS victim” and the “highly radioactive body” deserves more development. The underlying premise of the analogy points to specific precautionary measures taken by the funeral industry when embalming a body that has been exposed to any kind of radioactive substance. What makes the analogy significant is how much it reveals about the politics of handling an HIV/AIDS corpse in the 1980s. In the post-WWII decades leading up to the emergence of HIV/AIDS (and in large part because of Cold War politics), a corpse exposed to radiation had been regarded as one of the most dangerous kinds of dead bodies for the funeral industry. The radiation exposure could come from cancer treatments, but it might also arrive in much larger doses from industrial or workplace accidents.19 Most importantly, these different exposure scenarios all meant that even after an individual had died (from whatever cause), his or her dead body could in fact still contain radioactive isotopes used in medicine or could emit unhealthy levels of post-accident radiation.

The emergence of the HIV/AIDS corpse momentarily displaced the radioactive corpse as the major health risk confronting funeral directors. Indeed, the analogy succinctly illustrates the confusion and the stigma surrounding AIDS that turned these bodies into misperceived biohazard risks. The funeral director’s remark is additionally significant since it suggests that the extreme precautions taken to handle radioactive bodies should also be taken when handling the HIV/AIDS corpse. One of the radiation exposure precautions stipulates, for example, that a funeral director should not handle the corpse (even while wearing protective lead-lined gear) until “a radiation safety officer has certified the body as safe because of the possibility of gamma radiation.”20 The analogy’s central point is that the HIV/AIDS corpse was equivalent to the most dangerous and most labor-intensive public health hazard a funeral home could accept at that time.

In retrospect, the potential biohazards represented by radiation victims and HIV/AIDS corpses were scientifically incomparable. A highly radioactive dead body poses a far more serious threat to public health than the HIV/AIDS corpse, yet such scientific differences were not readily discernible within the industry at the time.21 Most dramatically, the funeral director’s analogy suggests that merely being in the same room with the HIV/AIDS corpse meant a funeral director would be exposed to potentially life threatening conditions. It also illustrates how central the combined technologies that classify, organize, and physically alter the human corpse are when confronted by an epidemic such as HIV/AIDS.

The term technologies of the corpse is partially derived from Michel Foucault’s articulation and theorization of what he calls “human technologies.” Foucault describes these human technologies as “the different ways in our culture that humans develop knowledge about themselves: economics, biology, psychiatry, medicine, and penology.”22 These technologies are used, Foucault suggests, to produce knowledge and understanding about the self in relation to others. This knowledge production, he argues, can be understood through these four interconnected categories: “(1) Technologies of production; ... (2) technologies of sign systems; ... (3) technologies of power; ... (4) technologies of the self.”23 Of course, it is not only the living body that is subject to these technologies. Through its control over the human corpse, for example, the modern American funeral industry can also be understood as deploying each of these technologies within a postmortem arena. But these technologies are more than just machines; they are ways of thinking about the productive possibility of the corpse and the avenues opened up by these technologies for changing the entire organic structure of the dead body. These technologies of the corpse also then encompass the machines, politics, laws, and institutions controlling the dead body.

Although all four technologies outlined by Foucault are relevant to discussing the productive potential of the HIV/AIDS corpse, the focus here is on his technologies of the self.24 This theoretical use of the technologies of the corpse, which is a step away from Foucault’s exact wording on human technologies, frames already existing postmortem tools in a way that is otherwise helpful and useful for living individuals to transform the corpse’s “postmortem self.” And while it is true that the dead body appears absent of any “self” or “subjectivity,” the living individuals that surround a human corpse produce countless (often competing) narratives about a deceased person. The self does not die with the person, rather it transforms into a new form of externally controlled, postmortem subjectivity. These changes imposed upon the dead body are thus a subtler, and by extension, more controlling form of technology, since a dead person lacks the physical ability to dispute most enacted transformations.

HIV/AIDS corpses presented two key problems when transforming the dead body. The first was the direct challenge posed by the virus to the institutional use of embalming machines and to the technicians operating those machines. The second problem was the challenge to the external control of an individual’s postmortem identity. Many of the institutions that physically altered the dead body for public viewing were simply refusing the work. If the corpse was left unembalmed and aesthetically unaltered, then obscuring the presence of HIV/AIDS in the dead person was all the more impossible. The invisible nineteenth-century technologies that produced new postmortem conditions through embalming were not only being made visible but also being rendered ineffective when dealing with HIV/AIDS. The HIV/AIDS corpse momentarily called into crisis the theory and practice of human control over how death visually appeared.

Universal Corpse Technologies

During the 1980s and early 1990s, the American funeral industry developed and received new rules, guidelines, and technologies from the federal government for the postmortem handling of infectious bodies, such as HIV/AIDS corpses. Those embalming precautions remain intact today and have not changed in any drastic way since the early 1990s.25 One organizational system that the funeral service industry uses requires “tagging” a corpse when a person dies.26 This tagging system, put in place prior to the 1980s, is used to readily identify the corpse’s cause of death. The act of attaching the tag to the dead body, either in the hospital or at the morgue, is the first step in categorizing the corpse for postmortem handling. In the September 1987 issue of The Director, Mayer used the following anecdote to explain the institutional importance of tagging in response to infectious diseases: “I prepared the body of a young female a few months ago. This young girl had a horrible weeping lesion in the right eye orbit. Two hours after the body had been brought to the funeral home, the hospital called to inform us the girl had a bad case of herpes. The bottom line is simply that today we must prepare every body practicing maximum sanitary measures.”27 Unless a postmortem tag is in place before the corpse arrives, the embalmer must assume that an infectious disease produced the body.

In 1991, in response to precisely these kinds of health concerns, the US Department of Labor and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) created uniform federal rules for the handling of all dead bodies. The rules were known as “universal precautions.”28 It was during this transitional moment that a new kind of postmortem universalization was indeed being created for the dead body. Mayer explains that using universal precautions means an embalmer will “treat all human remains as if they were infected with HIV, HBV [hepatitis-B] or other pathogens. In other words, the embalmer should treat all bodies with the same caution that would be applied for extremely hazardous, potentially fatal infections.”29 The following excerpt from a long essay by South Dakota funeral director Dalton Sanders will give the reader an idea of the labor involved in treating all human corpses “as if infected with HIV, HBV, or other pathogens” in order to embalm the body. The article, “Err on the Side of Caution,” appeared in the April 1997 issue of The Director and demonstrates how the confusion surrounding HIV/AIDS cases in 1987 was transformed, ten years later, into a series of rigorous, meticulous procedures. Sanders’s account describes the handling of a corpse when following the OSHA universal precautions:

My assistant and I wore nonpermeable gowns, heavy autopsy gloves, masks, safety glasses and shoe covers. Upon our return to the funeral home, we placed the body on a table after it was sprayed with a disinfectant. We then cleaned the cot with a bleach solution, and let stand to air dry, and then sprayed it again with a disinfectant. We first treated all open areas with a liquid preservative chemical, and then packed the nasal cavities and mouth with cotton soaked in the liquid preservative. Then, the entire body was washed with an antiseptic soap. After the initial body disinfection, we chose to use a very high index fluid mixture to ensure penetration would be effective, and chose the right common carotid as the point of injection. The embalming procedure itself went very well, with results that were comparable to a standard embalming. We paid particular attention to any splash or spillage, and cleaned it immediately with cavity fluid. All instruments were placed in one area and were disinfected with a bleach solution. We aspirated immediately following the operation to cover internal areas quickly with 32 ounces of [body] cavity fluid. Any areas that were open type lesions were covered with a cauterizing solution, and the body was then placed in full coveralls with the wrist openings tightly taped shut. The body was then sprayed liberally with a topical spray and covered with a sheet. Prior to dressing the deceased, we dressed as we had for the embalming stressing universal precautions, because the organism [MRSA] is transmitted by direct contact. Cosmetics were applied, (with the understanding that the brushes were soaked in a disinfectant upon the conclusion, and the handles were bleached), and a veil was used to discourage direct contact with the deceased.30

What is significant about this description is that the corpse was not in fact infected by HIV/AIDS, but given the ambiguity of the cause of death it had to be treated as though it was a hazardous case. By universalizing the potential hazard, the American funeral industry adapted to the complications produced by the HIV/AIDS virus with a system of institutional controls that made every human corpse a potential biohazard. In effect, and through the institutionalization of universal precautions, concerns over the HIV/AIDS corpse established a new standard for all bodies through those very same practices. Simultaneously, these processes came to treat all human corpses as though they were potentially epidemiologically hazardous and abnormal, even if a postmortem exam said otherwise. The result of these arduous procedures is that all bodies suddenly become universally safe to handle, touch, and view after cosmetics are applied. These institutional protocols are also an example of Foucault’s point that technologies for controlling the abnormal individual are ones that give rise to “theoretical constructions with harshly real effects.”31

The combined technologies of the corpse subsequently conducted the HIV/AIDS corpse through a two-step, oftentimes severe process. First, the technologies were used to categorize the HIV/AIDS corpse as an abnormal body through an array of regulations and guidelines dictating how the body should be handled. After the technologies were used to define the abject condition of the HIV/AIDS corpse, the same technologies were then applied to bring the dead body back into normal conditions. The postmortem individual connected to the HIV/AIDS corpse consequently became an aberration through the deployment of technologies that were then redeployed to make the dead person human again. The HIV/AIDS corpse was a monster made, not a monster born.32

And while the HIV/AIDS corpse presented problems for many funeral directors during this period, it also represented an opportunity to reorder the technologies of the corpse in new ways. One of the ways that some professional embalmers overcame the perceived health threat associated with the HIV/AIDS corpse was to effectively heroicize the work being done when embalming the HIV/AIDS corpse. In a July 1985 article in The Director entitled “AIDS—Identification and Preparation,” Jerome F. Frederick, then the director of chemical research for The Dodge Chemical Company (a major American embalming fluid manufacturer), argued: “Perhaps no threat has ever appeared on the health horizon like the one facing the professional embalmer today. The disease threat is AIDS ... and, despite constant research since it was first discovered among men in the homosexual community, it continues, after five years, to baffle our sophisticated medical establishment.”33 What both Frederick and Mayer suggested in those years was that even though the technologies made available to the professional embalmer and funeral director appeared threatened by HIV/AIDS, the tools must always overcome any challenge to altering the dead body. In order to preserve the theory, practice, and economic livelihood of those technologies, the transformation of the dead body needed to occur in spite of the perceived health risks and aberrant qualities projected onto HIV/AIDS corpses. In other words, the technologies of the corpse required reassertion even though funeral directors or embalmers were personally ill at ease around the dead bodies of, say, homosexuals or intravenous drug users. The entire point of deploying the technologies of the corpse was to enable living bodies to control dead bodies, not vice versa. Technologies preserving the corpse could therefore not be rendered useless by the very thing that the technologies were originally developed to manipulate: the dead body.

There is a final point worth noting on the transformative power of these technologies. Even though the HIV/AIDS corpse was a socially and medically different dead body than previously encountered by the technologies of the corpse, that body still possessed a transformable “self” if it was given proper care. So, when the HIV/AIDS corpse first appeared, embalmers and/or funeral directors were no longer strictly nineteenth-century preservation technicians. The technologies’ institutional administrator had gained the power (often through the direct orders of the family) to transform the corpse into an entirely different kind of person. Even though the HIV/AIDS corpse posed a challenge, an extreme health risk in the minds of some funeral directors, the postmortem transformation of the person who died became all the more possible with the technologies’ reordering. After dying, the transformation of the dead body meant entire histories of the deceased person’s life could be obscured, even left unknown, given the power of the technology to alter an individual’s attributes. Who and what that “postmortem self” became then meant embalmers and funeral directors using the technologies of the corpse had great power to transform the HIV/AIDS corpse back into a human being much different in death than perhaps ever in life.

The emergence of the HIV/AIDS corpse in the 1980s turned the dead body into something quite different than it had been a century before for American funeral directors. Compounding these problems were funeral directors who refused to handle these bodies, meaning the technologies invented a century earlier to standardize the human corpse were suddenly useless without an operator. The institutional history of postmortem preservation, stressed by the American funeral industry, also seemed at odds with the fear many embalmers expressed at the very idea of touching bodies produced by HIV/AIDS. The previous century’s postmortem technologies and ways of thinking about dead bodies did not seem to initially work when applied to HIV/AIDS corpses. This epistemic shift redefined the dead body, so much so that different postmortem technologies at the levels of both thought and practice were developed and deployed by the American funeral industry in order to control the HIV/AIDS corpse.

The HIV/AIDS Corpse and Queer Politics

In AIDS and the Body Politic, Catherine Waldby outlines and critiques the scientific rhetoric defining the AIDS epidemic, as well as the characterizations of human sexuality attached to the virus. One of Waldby’s central arguments defines “AIDS as a symptom, not of the activity of a virus, but of a particular moment in the history of sexual politics.”34 The American funeral service industry found itself enmeshed in that historical moment, and the projection of human sexuality (rational or not) onto dead bodies forced an institution-wide and often very heteronormative redefinition of the human corpse. This redefinition resulted in the HIV/AIDS corpse becoming a politically productive body that altered both institutional codes and technological conventions.

In the conclusion to AIDS and the Body Politic, Waldby cites Judith Butler’s suggestion that terms such as “queer” and “queer politics” raise “the question of ‘identity,’ but no longer as a pre-established position or uniform entity; rather, as part of a dynamic map of power in which identities are constituted and/or erased, deployed and/or paralyzed.”35 Waldby expands Butler’s argument with the suggestion that “perhaps queer is also an attempt to rework relationships between identity, contagion, and death, an ethical task of the self which the advent of AIDS has made so urgent.”36 Waldby’s ethical task also suggests that the HIV/AIDS corpse needs to be recognized for its significant productivity in queer politics, that is, that it radically reworked death and dying’s social and political dynamics by challenging the technologies that pathologized a person who died from AIDS. In death, the HIV/AIDS corpse produced a moment of paradoxical “postmortem agency” for an individual who might otherwise have remained silent.

In a 1992 essay for The Director on precisely this issue of pathologization, social worker Michael Hearn wrote a testimonial piece about the conflicts between different groups (families, lovers, friends, etc.) when acknowledging the identity, contagion, and death of a person who died of AIDS. Hearn describes attending the HIV/AIDS funeral as a regular occurrence during the 1980s and a situation where the body in the casket was fixed with new and conflicting meanings. He writes: “As a gay man, I’ve watched the issue of AIDS become a springboard for the hate of an entire population. I’ve cried the tears of a lifetime at funerals where the dead are remembered for having wasted their lives. Where the casket serves as the dividing line (relatives to the left, “us” to the right). ... And I’ve listened to the litanies, the soliloquies, and monotonies where illnesses are covered up or described with pretty words.”37 A few years later, in a 1996 article for The Director, Iowa funeral director Michael Lensing detailed how best to negotiate potential conflicts between groups of mourners who maintained different kinds of relationships with the deceased. He suggests the following tactics: “We are often trying to balance two families at the time of death—the biological and the chosen—trying to satisfy the emotional and psychological needs of both. It may be necessary to divide cremated remains in half to disperse in different locales by different survivors. ... Be sure to find out who is legally in charge.”38

The legal distinction between the chosen and the biological family often meant that the lawful standing of biology outweighed kinship choice. This also meant that the law could, and often would, exclude a chosen family from placing any claim to the biological family’s dead body. The legal responsibility of the funeral service industry to the biological family, as mandated by the state, potentially risked the chosen family’s complete erasure. The state’s judgment regarding who received the bodily remains became less a question of family than a question of property ownership.39 While the biological family may have had legal rights to the body, those who cared for the deceased were often left with no legal standing.40 Kath Weston underlines the fictitious, but no less real distinctions between a chosen and a biological family structure when she argues that “the standardized ‘American family’ is a mythological creature, but also ... an ideologically potent category.”41 These family group reconceptualizations marked an important moment for the HIV/AIDS corpse and queer politics, as the legal right to the body highlighted questions of sovereign power and technologies of control over the self. Politically active queer politics, endowed with such urgency by HIV/AIDS during the 1980s, also illuminated the broader conflict between an ethical claim and the legal right to possession of postmortem human remains.42

In the History of Sexuality, Volume I, Foucault begins the final essay, “Right of Death and Power over Life,” by explaining “for a long time, one of the characteristic privileges of sovereign power was the right to decide life and death.”43 The pathological positioning of the HIV/AIDS corpse offered a new opportunity for sovereign authorities, that is, the people with a legal right to the corpse, to exercise power over the individual well beyond the individual’s death. The power exercised was not so much the sovereign’s decision about life and death since the bodies involved were already dead. But even if the question of death was answered, it did not mean that the dead person involved was without the possibility of living another kind of life. That other kind of life, one unfettered by the dead self associated with HIV/AIDS, is best demonstrated by the technologies of the corpse transforming the human deviant into a new kind of normalized individual.

If queer politics is to forge a different kind of identity and make sense of living, per Waldby’s suggestion, then these formulations about life must also make sense of death. The HIV/AIDS corpse is that thing—neither a complete subject nor entirely an object—that refuses to go silently, no matter the controls exercised by sovereign power under the legal right of the state. The HIV/AIDS corpse might one day be recognized as having had a paradoxical agency that embodied Waldby’s ethics and challenged how state power exercised control over dead bodies.44 The irony of this situation is that the socially abject, HIV/AIDS corpse will have caused these changes for the postmortem politics of all American bodies.

Postscript on the Temporality of HIV/AIDS

In 1992, the Infectious/Contagious Disease Committee of the Funeral Directors Services Association of Greater Chicago commissioned a study to determine how long the HIV virus remained active in a body after the host died. The results of the study, published in the January 1993 issue of The Director, are well worth mentioning here, if for any reason, the study found that “for unknown reasons the viability of the virus appears to be time-dependent following death,” that in twenty-one of forty-one subjects, scientists “were able to isolate the virus up to 21.15 hours after the patient’s death. No virus was found after that time, and refrigeration of the deceased did not significantly affect the virus’s survival rate.”45 Assuming that a new mutation of the virus has not invalidated this study, an HIV virus that expires after less than twenty-four hours changes (biomedically speaking) the status of the HIV/AIDS corpse. If a corpse ceases to be infectious after that amount of time, then that body should, in theory, remain nonthreatening for the funeral. On a sociocultural level, of course, that reality has not and likely will not register in the near future for the HIV/AIDS corpse. Once the technologies of the corpse mark a body with HIV/AIDS, undoing those signifiers is difficult at best.

Yet a point left to ponder is the temporality of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.46 Assuming that the epidemic will continue for some time, then the institutional changes that altered both the funeral industry and how funeral directors handle human corpses will most certainly endure. In 2020, the same universal precautions created during the early 1990s remain standardized procedures and underscore the central significance of the HIV/AIDS corpse: the invention of an entirely new kind of dead body that brought the technologies transforming these bodies into public view and debates.47 Of course, the institutional arguments taking place within the funeral industry were not always in public view, but the resulting changes most certainly appeared on view for the public.

The HIV/AIDS corpse was, in so many words, a useful body for the technologies of the corpse, presenting entirely new opportunities for changing how previously used machines interacted with the dead body, as well as defining the limits of sovereign authorities’ power. More than anything, the treatment of the HIV/AIDS corpse demonstrates how in flux the concept of the human corpse can become when seemingly inert dead bodies begin destabilizing the previously held regimes of knowledge defining death.

In closing, it is important to point out that through popular imagination, a general lack of knowledge, and certain funeral industry practices, the HIV/AIDS corpse became the most threatening dead body of its time. The productive potential of the AIDS epidemic can, as a result, be partially located in the invention of this new kind of corpse. In hindsight, it is clear that only an epidemic as pervasive, resistant, pathologized, and deadly as HIV/AIDS could have initiated the funeral industry’s massive institutional changes to well-established technological practices. What the temporality of HIV/AIDS may yet produce is something beyond a corpse—a dead body that maintains a politically active position without the privilege of vitality. The technologies of the corpse are always at work classifying, organizing, and physically altering the corporeality of the dead body. Changes produced by those technologies, including the codification and normalization of abject corpses, have undoubtedly drawn attention to the fallacy of control often attached by the public to modern death practices. The early decades of HIV/AIDS in America may become recorded as an historical moment wherein corpses emerged within the politics of death as a new kind of dead body—one that confounded the technologies of regulation and control in everyday life.

8/06/2018

Watching My Sister Die—#19. Julie’s Funeral

I can’t cross your funeral off the list, little sister.

And I won’t.

I knew this even before I wrote it down

on my weekly list

Like an ordinary task right after 18. Gym.

It’s taken me these past six-days to actually

open the pen cap and stare at this page

Stare out this airplane window

leaving all of you behind

Having touched your dead hand and kissed you goodbye

when I arrived.

Finding ourselves, like we did as children, in a mortuary

and feeling completely at home holding your marble white

skin

Your face frozen now with release.

And I brought Mom & Dad to you → keeping my promise

Making sure that they were ok.

Because little sister I feel your absence now in

the silence

In the quiet of you not yelling at me about my life.

So I laugh little sister and I cry and I look at photos that

represent us in multiple ways. The decades of our lives.

The smiles at the end that hid the pain.

The promises you made me make to look after your children.

And Mom & Dad, who I know will join you sooner than I want.

Reminders of you throughout your house in all the little things,

the clothes, the box of tampax, the coffee machine

that you used right up until you died.

The bed where you laid, in the basement, when you could no

longer walk. Holding my hand as we talked about dying.

Me sleeping in this bed, when I arrived, after you died

smelling your hair, the same hair I smelled at the mortuary,

on the pillow.

I watched you die little sister. Over 365 Days.

Realizing now that I could have done more to expedite your

pain relief.

Intervening sooner. At your birthday party when I knew that

there would be no more.

But I didn’t and I’ll forever wonder why

what part of my personal life overrode my professional knowledge.

Then being there for your husband when he needed me.

Going with him to file your death paperwork

All the forms that needed signing to say that you no longer lived.

staring at those forms with your husband and watching

him sign them all.

On his birthday and on that day for the rest of his life.

Here I go little sister. Up into the air. Leaving where you’ve already left.

Everything’s different now, little sister, and strangely the same.

A vast blurring of how I understood death.

And in this Patient Zero moment I realize now that I knew very little until I

stared at #19. Julie’s Funeral.