Within a month of landing at Sydney, John Bigge was in dispute with Lachlan Macquarie over the appointment of the emancipist surgeon, William Redfern, to the magistracy. Over the next fifteen months of his inquiry the commissioner reached conclusions about the future of the Australian colonies sharply at odds with those of the governor. The two men were divided by background, training, temperament, and expectations of empire. Macquarie, a career soldier, always viewed New South Wales as a ‘penitentiary or asylum on a grand scale’. It was destined to grow from a penal to a free society and ‘must one day or other be one of the greatest colonies belonging to the British Empire’, but that would depend upon the rehabilitation of its convicts under his tutelage. Bigge, a cool and systematic younger man, brought a lawyer’s judgement and a tendency to weigh local circumstances by English standards.

The two men belonged to different generations, represented different eras. Macquarie, in his late fifties, spanned the collapse of clan society in the Scottish Hebrides and the remaking of his nation into north Britons in the service of the Empire. He combined the eighteenth-century values of reason and sentiment with the habit of command, and the regularity he sought was one tempered by paternalism and patronage. Now, after his forty years of military service, the Empire was at peace. The defeat of Napoleon left Britain free from external threat, and the enormous effort of war could be diverted into commerce and industry. Through a series of political and administrative reforms the imperial state reduced its fiscal burden and increased its efficiency. The engrossment of wealth by restrictive regulation and exclusive trading gave way by degrees to an open market in which all could participate. Free trade and the maxim laissez faire, let things be, became by the middle of the nineteenth century the guiding principles of British policy.

As the logic of the market took hold, it entered into every aspect of human life. A social order based on rank and station, in which relationships were personal and particular, yielded to the idea of society as an aggregation of autonomous, self-directed individuals, everyone seeking to maximise their own satisfaction or utility. The Utilitarians, the group of single-minded reformers led by Jeremy Bentham who reshaped public policy, propounded a simple behavioural algorithm: given appropriate institutional stimuli, the impulse of the human actor to pursue pleasure and avoid pain would be channelled into choices conducive to the general benefit.

Bigge, as a public official committed to the rule of law and still in his mid-thirties when the wartime emergency ended, was an early agent of the corresponding transformation of colonial policy. In criminology, as in political economy and most branches of social policy, the effect was to reconstruct the subject as an object of bureaucratic administration: precise, uniform and efficient. The wrongdoer must be deterred. Bigge was accordingly to inquire into the prospects of New South Wales both as a gaol and a colony, to rein in its costs and make it more profitable. Above all, his instructions from the minister for the colonies emphasised that transportation should be rendered ‘an object of real terror’.

His three reports, presented in 1822 and 1823, suggested how punishment could be reconciled with profit. Deterrence called for greater severity in the punishment of convicts through greater regularity. They should not be given special indulgences or allowed to earn money in free time to spend on town pleasures, but instead be assigned to rural labour under strict supervision. They should not receive land grants on expiry of their sentences but continue to work for a living. They should not be admitted to positions of public responsibility but rather remain in a subordinate status. Bigge’s recommendations on the penal system simultaneously defined the future development of the colony. It would rest on free settlers who would possess the land, employ the convicts and grow wool – John Macarthur had caught his ear. It would require a system of government suitable for free subjects of the Crown: a legislature to curb the governor’s arbitrary powers and a judiciary to safeguard the rule of law.

With the implementation of these recommendations the colonial presence in Australia was transformed. Pastoralism flourished, and the greatly increased numbers it attracted burst the limits of settlement. Explorers and surveyors opened up the interior, and new colonies were planted on the southern and western coasts. Relations between Aboriginals and settlers on the vastly extended frontier deteriorated into endemic violence. Stricter supervision of the greatly increased numbers of convicts exacerbated conflict between the emancipists and the exclusives. The restraints on rule by decree opened up a three-cornered contest for power between these two groups and the governor. Australia was incorporated into an empire of trade, technology, manners and culture, while at the same time its own distinctive forms became clearer.

***

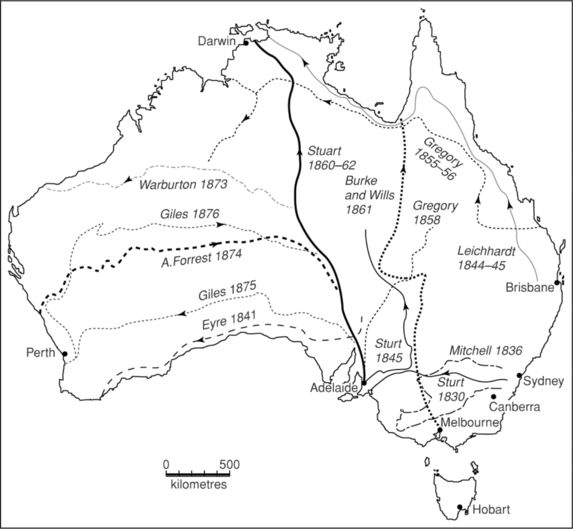

The internal exploration of the country proceeded rapidly after the crossing of the Blue Mountains in 1813. A series of expeditions from 1817 followed the inland river system that drained from the western plains of New South Wales into the Murray, and by 1830 traced that river to its outlet on the south coast. Northern ventures pushed from the Hunter Valley through the high country of New England onto the Darling Downs in 1827 and well into Queensland by 1832. A journey south to Port Phillip was made in 1824, in 1836 the grasslands of Western Victoria were traversed and in 1840 a route through the Snowy Mountains into Gippsland was found. By this time the topography and resources of southeast Australia had been ascertained.

The explorers are central figures in the colonial version of Australian history. Celebrities in their own time, they were commemorated afterwards with statues and cairns, celebrated in school textbooks – even today, schoolchildren trace the paths of their journeys onto templates of an empty continent. They figured as exemplary heroes of imperial masculinity: visionary individuals who penetrated into trackless wilderness, survived attacks by savage and treacherous natives, endured hunger and thirst in their endeavour to know the land. More recent writing has undermined this heroic status. The epic version of exploration history left out the role played by sealers and drovers, travellers and outcasts who often preceded the explorer. When John Wedge, the assistant surveyor of Van Diemen’s Land, made his journey of discovery into the mountainous southwest in 1826, he discovered the hideout of a bushranger. When Thomas Mitchell, the chief surveyor of New South Wales, reached the Victorian coast in 1836, he found a collection of whalers’ huts and nearby a family farm.

Land exploration.

The celebrants of exploration also minimised the role played by Aboriginal guides. Mitchell employed three of them, and while he exulted in ‘a land so inviting and still without inhabitants’, scarcely a day passed without him recording in his diary an encounter with the owners of that land. Once the Aboriginal presence is acknowledged, the idea that the explorers were engaged in a process of discovery yields to the realisation that they were superimposing their own form of knowledge for their own purposes. Thomas Mitchell recorded in his journals an affray on the Murray River in 1836: the Aborigines ‘betook themselves to the river, my men pursuing them and shooting as many as they could … Thus, in a short time, the usual silence prevailed on the banks of the Murray, and we pursued our journey unmolested’.

Major Mitchell was a Scottish career soldier who brought the survey techniques he had learned on the Spanish battlefields of the Napoleonic Wars. Some of the epic feats of land exploration in the nineteenth century were performed by Britishers born too late to win martial glory. For them the conquest of unknown territory was proof of manhood in imperial service – a tradition that continued right up to the eve of the First World War with Robert Scott’s dash to the South Pole in 1912. In Australia it culminated with an equally vainglorious expedition from the south to the north coast, led by an Anglo-Irish adventurer, Robert O’Hara Burke, who perished in Central Australia in 1861. By then the locals were achieving greater success. They travelled more lightly in the outback, had fewer preconceptions, adapted equipment to local conditions.

The pastoral occupation proceeded apace. During the 1820s stockholders moved out of the Cumberland Plain, over the Blue Mountains and along the inland creeks and rivers. To contain them in 1829 the governor declared nineteen counties that stretched some 200 kilometres from Sydney, these constituting the limits of location in New South Wales. In Van Diemen’s Land the lines of settlement north and south of the estuarine bases met in 1832 and quickly broadened. Sheep numbers on the mainland increased from 120,000 in 1821 to 1 million in 1830, and from 170,000 to another million in the island colony. Production of other livestock, especially cattle, and cultivation of cereals also increased rapidly, but these were for domestic consumption while wool was exported and in the next two decades sheep surpassed all other instruments of the European economy. They were the shock troops of land seizure. New South Wales flocks numbered 4 million in 1840 and 13 million in 1850. By then there were some two thousand graziers operating on a crescent that stretched more than 2000 kilometres from Brisbane down to Melbourne and across to Adelaide.

Australian sheep produced wool for British manufacturers to spin and weave. The mechanisation of textile production began the industrial revolution that turned Britain into the workshop of the world. While Lancashire’s cotton industry was the more spectacular, the mill towns of Yorkshire turned out ever-increasing quantities of woollen cloth, garments, blankets and carpets that consumed ever-increasing volumes of fine wool. Between 1810 and 1850 British imports of fleece increased tenfold. First Spain and then Germany catered to this growing demand, but as Australian producers improved the quality of their wool with the introduction of the Merino breed, they captured an increasing share of the British market – one-tenth in 1830, a quarter in 1840, half by 1850. By then sales of Australian wool amounted to over £2 million per annum, more than 90 per cent of all exports. Here was the staple that sustained Australian prosperity for a century.

It was produced in circumstances that allowed newcomers to achieve rapid success: plentiful land at minimal cost, a benign climate that required no handfeeding in winter, a high-value product that could absorb transport costs. Such opportunities attracted army and naval officers discharged after the Napoleonic Wars, and younger sons of gentry families in England and Scotland who sought their own estates. An entrant required some initial capital to buy stock; he then hired labour and drove his animals to the edge of settlement; laid claim to an area that might extend 10 kilometres or more; arranged his flocks under the care of shepherds who pastured them by day and penned them by night; put rams to the ewes to build up numbers; clipped the fleece, washed and pressed, and dispatched it for sale.

There were fortunes to be made in this first, heady phase of the pastoral industry, but it was a young man’s calling and not one for the faint-hearted. Drought, fire or disease might ruin the most resolute. A downturn in British demand at the end of the 1830s caused prices to tumble, and millions of sheep had to be boiled down for tallow. The insecurity of conditions, as well as the absence of land title, kept the pastoralist’s eye fixed on speedy returns so that beyond improvement of stock lines, there was little effort to increase efficiency or conserve resources. Stock quickly ate out native grasses. The cloven hoof hardened the soil and inhibited regrowth. Patches of bare earth round the stockyards, eroded gullies and polluted water-courses marked the presence of the pastoral invader.

So did the signs of human loss, the ruined habitats and desolate former gathering places of the Aboriginal inhabitants, the skulls and bones left unburied on the sites of massacres, and the names that became associated with some of them. There was ‘Slaughterhouse Creek’, on the Gwydir River of northern New South Wales, where perhaps sixty or seventy were ‘shot like crows in the trees’ in 1838; ‘Rufus River’ on the lower Murray where the water ran red in 1841; and other such places that recorded past atrocities with chilling frankness: ‘Mount Dispersion’, ‘Convincing Ground’, ‘Fighting Hills’, ‘Murdering Island’, ‘Skull Camp’. White settlers sometimes suppressed the memory of such disturbing events and sometimes preserved it in local lore, so that in a pub conversation in rural New South Wales 170 years later an old hand could relate how the firstcomers had ‘rounded all the blackfellas up at the top of the gorge, and shot at them till they all jumped off’.

Aboriginal versions of these encounters have an additional dimension. Their stories are at once specific and cumulative, telling of particular events at particular places and of their larger meaning. ‘Why did the blackfellows attack the whites?’ the South Australian commissioner of police asked Aboriginal survivors after the Rufus River affray. ‘Because they came in blackman’s country’, he was told. Far from obliterating the Indigenous presence, the white onslaught produced an enlarged awareness of a pattern of conquest that began with the first British landfall. ‘You Captain Cook, you kill my people’, expostulated a Northern Territory stockman in the 1970s.

The violence was on such a scale that white colonists spoke during the 1820s and 1830s of a ‘Black War’ – but uneasily, for the conflict did not lend itself to a romance of heroes and martial valour; the predominant attitude was one of ‘fear and disdain’. Talk of a frontier war was quickly abandoned, and has resurfaced only recently as the Aboriginal presence in Australian history has been more fully restored. In 1979 the historian Geoffrey Blainey suggested that the Australian War Memorial should incorporate a recognition of Aboriginal–European warfare. In 1981 the pre-eminent white historian of frontier contact, Henry Reynolds, argued that the names of the fallen Aborigines be placed on our memorials and cenotaphs ‘and even in the pantheon of national heroes’.

Some historians query the emphasis on frontier violence and destruction, and suggest that the martial interpretation fails to understand Aboriginal actions in their own terms. The pastoral incursion was undoubtedly traumatic. Indigenous populations shank dramatically (one national estimate suggests from 600,000 to fewer than 300,000 between 1821 and 1850), but disease, malnutrition and infertility were the principal causes. Aboriginal survivors responded to this disaster with a variety of strategies, and accommodation was one of them. During the 1830s and 1840s they incorporated themselves into the pastoral workforce as stock workers, shepherds, shearers, domestic servants and sexual partners. There was loss, but there was also persistence.

The idea of a Black War attests to the extent of Aboriginal resistance. In Van Diemen’s Land, where in a single month of 1828 there were twenty-two inquests into settlers killed by Aborigines in the outlying district of Oatlands, the governor declared a state of martial law. After parties of bounty hunters failed to quell the threat, he ordered 3000 men to form a cordon across the island and drive the Aborigines southwards to the coast. This Black Line, 200 kilometres in length, captured just one man and one boy, and even while it was moving down the island during 1830, four more settlers were killed and thirty houses plundered.

More than five hundred soldiers were employed in Van Diemen’s Land as part of the futile Black Line in 1830 and afterwards for punitive purposes. The governor of the infant colony in Western Australia led a detachment of the local regiment into the Battle of Pinjarra of 1834, when perhaps thirty of the Nyungar were shot, and military garrisons were deployed in the other new settlement in South Australia as late as 1841. Alternatively, the governors deployed forces of mounted police, and subsequently mounted native police. The mobility and firepower of such paramilitary forces were difficult to withstand, and the enlistment of Aborigines allowed the British to follow the common imperial device of using conquered peoples to overrun the remaining independent societies. Under the command of Major James Nunn, the mounted police of New South Wales conducted a ‘pacification’ expedition during 1838 that inflicted heavy casualties on the Kamilaroi people of the northern plains.

Yet these set-piece encounters again give a misleading impression of the conflict. When trained men fell on assemblies of Aborigines in open country, the firearm prevailed over the spear, especially after the repeater rifle replaced the musket. Aboriginal warriors had no fortifications, and made little use of their enemies’ military technology. In contrast to the Maori, who tied up 20,000 British troops in New Zealand for twenty years, they could not sustain a formal warfare of massed battle. They quickly learned to avoid such encounters, and typically used their advantages of mobility and superior bushcraft to conduct guerilla resistance. Destruction of livestock and surprise attacks on pastoral outstations exacerbated the fear and insecurity of white settlers ‘waiting, waiting, waiting for the creeping, stealthy, treacherous blacks’.

The result was a particularly brutal form of repression conducted by the settlers themselves. The most notorious instance occurred in 1838 near the Gwydir River at Myall Creek in northern New South Wales, when a group of stockmen riding in pursuit of Aboriginals wanted for spearing cattle came instead upon a party of Kwiambal people, mostly women and children, who had taken shelter with a hutkeeper. There was goodwill between the men of the station and the Kwiambal, who cut bark, helped with the cattle and were allowed to keep up their hunting of game; several of the Aboriginal women had formed relationships with the white men. There was foreboding and irresolution among the station hands when the white vigilantes took the Aborigines into the bush and butchered the entire party. There was bombast from the murderers when they returned alone, and then furtive guilt as they returned to try to destroy the remains of their victims. We know about the Myall Creek massacre because the station overseer reported it at a time when the governor had been put on notice by the British government that such atrocities were not to be condoned. He brought those responsible to trial, and when a Sydney jury found them not guilty, ordered a retrial.

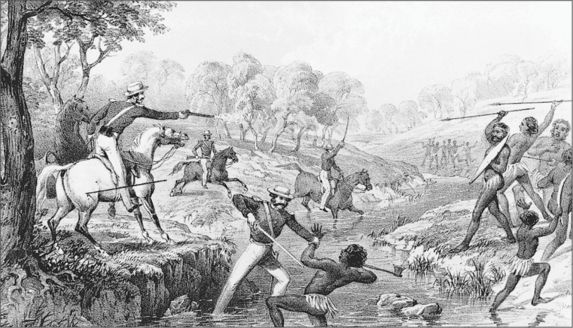

Guns against spears – mounted troopers do battle with Aboriginal warriors across a creek. This portrayal of a violent encounter on the pastoral frontier suggests that the invaders will prevail, though the adversaries are more evenly matched than they would be after repeater firearms replaced the musket.

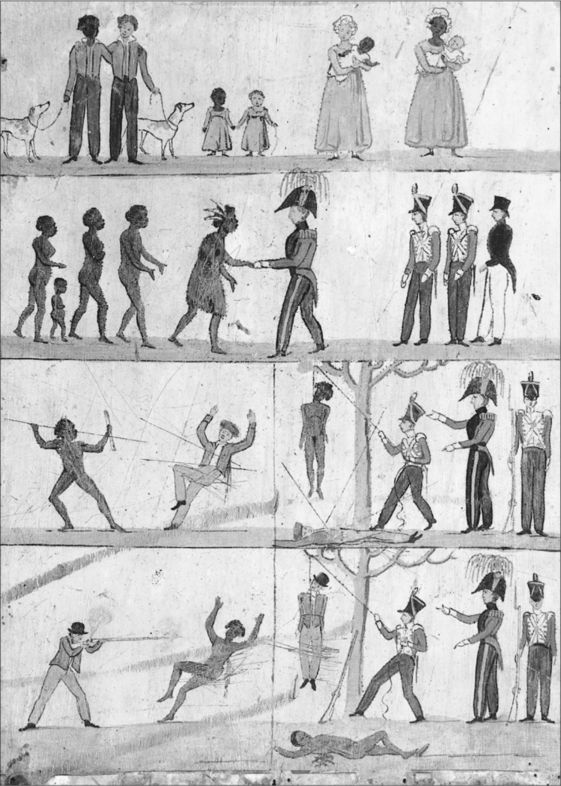

Seven of the murderers were eventually convicted and executed, an outcome that astounded most colonists. The official response to the Myall Creek massacre was quite exceptional, both in the decision to prosecute and in the availability of white witnesses prepared to give evidence against them. Since Aborigines could not swear on oath that they would tell the truth, they were unable to testify against those who did them injury. The ostensible even-handedness of British justice – proclaimed by Lieutenant-Governor Arthur of Van Diemen’s Land in a message board that depicted first a black spearing and then a white shooting, each treated as crimes and each punished – rested on a fundamental inequality. In both panels it was the white man who prescribed the rules and meted out the punishment. The Aboriginal rejoinder to such one-sided justice was delivered in the year that Arthur conducted his Black Line: ‘Go away, you white buggers! What business have you here?’

George Arthur, the lieutenant-governor of Van Diemen’s Land, issued this pictorial proclamation in the same year that he declared martial law. The upper panels promote inter-racial amity, the lower ones indicate the penalties for violence. Arthur himself appears in official dress as the embodiment of authority and justice.

Earlier encounters between Aborigines and colonists had established the fundamental incompatibility of two ways of life. The Aborigines had tried through negotiation and exchange to incorporate the Europeans into their ways, but the Europeans had little desire to assimilate into Aboriginal society. Even so, the restricted nature of colonial settlement up to the 1820s left open the possibility of some form of coexistence. The rapid extension of the pastoral frontier removed that possibility since it resulted in a succession of sudden, traumatic encounters. There was still room for both peoples, for the Europeans spread along open grasslands, leaving the more heavily timbered higher slopes, and some initial accommodation based on mutual exchange of goods and services did occur. But Aborigines were loath to accept the occupation of their hunting ranges and despoliation of their waterways, while pastoralists commonly responded to stock losses with unilateral action aimed at nothing less than extermination of the original inhabitants. The colonial authorities, having set this lethal chain reaction in motion, were unable to prevent the spread of killing.

There were some whites who recoiled before the enormity of their compatriots’ actions, who perceived that such inhuman conduct compounded the unjust expropriation, and who warned that ‘the spot of blood is upon us’. The evangelical activists who campaigned against slavery in Britain’s plantation colonies, and secured its abolition in 1833, mounted a similar case against the abuses committed in the settler colonies. In both instances they proclaimed a sacred duty to protect, convert and redeem ‘the untutored and defenceless savages’. The agitation led to the establishment of a select committee of the House of Commons, which found in 1837 that the colonisation of South Africa, Australia and British North America had brought disastrous consequences for the native people: ‘a plain and sacred right’, an ‘incontrovertible right to their own soil’, had been disregarded.

The British government was already concerned by reports of massacres and the use of martial law against the natives of the Australian colonies. ‘To regard them as aliens with whom a war can exist’, the minister for the colonies wrote to the governor of New South Wales in 1837, ‘is to deny that protection to which they derive the highest possible claim from the sovereignty that has been assumed over the whole of their ancient possessions’. He insisted that the Aborigines be protected.

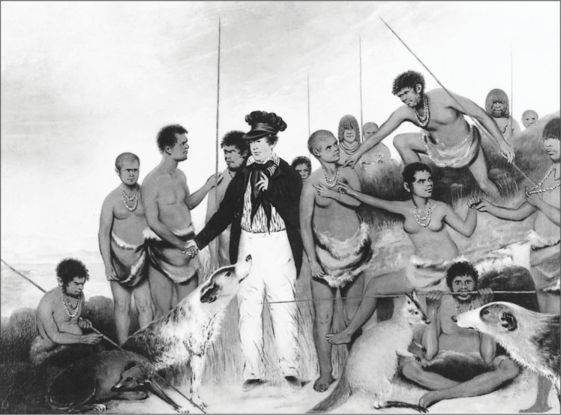

In 1929 Lieutenant-Governor Arthur commissioned George Robinson to make contact with the remaining Aborigines of Van Diemen’s Land and persuade them to settle on a reserve. Benjamin Duterrau’s 1840 painting, The Conciliation, shows a man of peace and compassion. Despite his promises to the Aborigines of Tasmania, Robinson arranged for them to be deported to Flinders Island.

None of the schemes of protection was successful. In Van Diemen’s Land, Lieutenant-Governor Arthur had already commissioned a local tradesman, George Robinson, to round up the remaining Aborigines. Robinson’s ‘friendly mission’ employed Aboriginal companions to succeed where the Black Line had failed. Between 1830 and 1834 he conciliated and captured the last defiant Aborigines and placed them on Flinders Island, in Bass Strait, where their numbers declined until the survivors were returned to a reserve near Hobart in 1847. Similar reserves or mission stations were established on the mainland during the 1820s and 1830s, usually by Christian missionary societies with government support. Some well-wishers, including the judge who presided over the trial of the Myall Creek murderers and who had earlier experience at the Cape Colony, wanted larger reserves on which the natives might be settled and protected from the perils of white civilisation.

Settlement was a word of many meanings. The Aborigines were to be settled so that colonial settlement could proceed unhindered: indeed, one of the Myall Creek culprits announced that he and his mates had ‘settled’ the ‘blacks’. The governors of New South Wales, however, preferred incorporation to segregation and appointed white protectors to accompany Aborigines in their wanderings and help settle them. George Robinson became the chief protector of Aborigines in the Port Phillip District, sometimes able to curb the worse abuses, powerless to prevent the continuing encroachment on their lands.

Another course of action was possible. The settlement of the Port Phillip District began in 1835 when a group of entrepreneurs from Van Diemen’s Land led by John Batman crossed Bass Strait. In return for a payment of blankets, tomahawks, knives, scissors, looking-glasses, handkerchiefs, shirts and flour, and an undertaking to pay a yearly rent, they claimed to have received 200,000 hectares from the Kulin people. This unofficial and contrived agreement fell a long way short of the treaties negotiated by British colonists with indigenous people in New Zealand (it was more like the ‘trinket treaties’ arranged in the American West), but did suggest some acknowledgement of Aboriginal ownership. The minister for the colonies dismissed the arrangement on the grounds that ‘such a concession would subvert the foundation on which all property rights in New South Wales at present rest’.

It was at this point that the official policy of Aboriginal protection succumbed to the land hunger of the settlers. Settlement on the mainland had hitherto been restricted to the nineteen counties. Its boundaries were already transgressed and 1836 Governor Bourke charged annual payments for those depasturing stock beyond the limits of settlement. This licence system ran counter to the official policy of concentrating settlement, but Bourke argued that ‘sheep must wander or they will not thrive, and the colonists must have sheep or they will not continue to be wealthy’.

Batman and his colleagues had no licence, so theirs was an illegal settlement, but it occurred at the very time Mitchell reported the rich grasslands south of the Murray. Rather than evict the trespassers, Bourke came down to the squatters’ camp, named it Melbourne, and allowed a frenzied land rush that by 1842 extended pastoral leases over more than half the district. A recent historian sees this decision as conceding ‘the right of settlers to live where they chose’ and thereby determining ‘the conquest of Australia’. The paradox was that at the very moment when the Colonial Office in London was emphasising the need to protect the indigenous people, its local administrators allowed settlers to invade their land – indeed, it is likely that the £20 million the British government paid at this time as compensation to slave-owners provided much of the capital for the pastoral invasion. Try as the colonial authorities might to follow instructions to restrain violence, they were simply incapable of policing the vastly extended zone of dispossession.

In 1836 the Colonial Office also insisted that the new colony proposed for South Australia must respect the ‘rights of the present proprietors of the soil’, and its commissioners stipulated that the land should be bought and a portion of purchase price paid to the Aborigines. The South Australian settlers ignored these conditions. Similarly, the warning of the governor in his proclamation of the colony that he would ‘punish with exemplary severity all acts of violence and injustice which may be practiced or commences against the Natives’ gave way within four years to summary execution of two Aboriginal men identified on the basis of hearsay as responsible for killing a party of shipwrecked colonists. An early pastoralist in South Australia said that those who were displaced for sheep ‘were looked upon as equally detrimental with wild dogs’.

Within five years the Aboriginal people on the outskirts of the new settlements at Melbourne and Adelaide were reduced to beggary. In Sydney their numbers dwindled and by the 1840s most were camped near the heads at Botany Bay. An old man there, ‘Mahroot’, told an English visitor of the changes he had witnessed: ‘Well Mitter … all black-fellow gone! all this my country! pretty place botany! Little pickaninny, I run about here. Plenty black-fellow then, corrobbory; great fight; all canoe about. Only me left now, Mitter – Poor gin mine tumble down, All gone!’

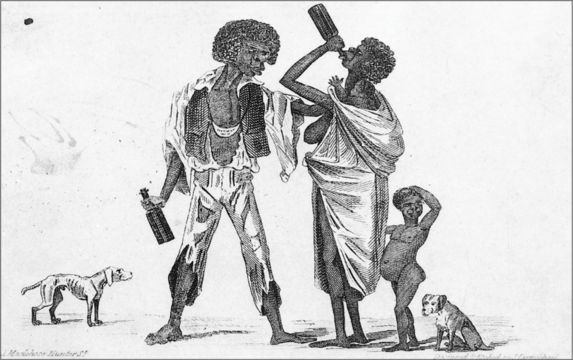

An 1839 depiction of Aborigines in Sydney, degraded by alcohol. The male figure still wears a breastplate, but his ragged clothing and dissolute appearance declare that the earlier effort to incorporate Aborigines into the colonial order had failed.

White town-dwellers complained of the riotous dissipation and drunken squalor of these Aboriginal residents. White artists caricatured them as semi-naked figures who sprawled over public spaces with tobacco, alcohol, mangy dogs and neglected children, shameless in their vices and incapable of responding to the virtues of civilisation. Such representations of Aboriginal depravity established the victims as responsible for their fate, but there were alternative and far more disturbing images of the wild and untamed native. Captivity narratives circulated of white men who fell into the hands of Aborigines and returned to a state of nature, or of white women who survived their ordeals in the wild.

The most celebrated of these was Eliza Fraser, who survived a shipwreck in 1836 and for fifty-two days lived with the Nglulungbara, Batjala and Dulingbra peoples on an island off the coast of central Queensland. Her ‘Deliverance from the Savages’, as the title of one of many contemporary publications put it, dwelt on the killing of her husband and male companions, and the sexual degradation of an unprotected white woman. Fraser herself appeared as a sideshow attraction in London’s Hyde Park, telling her tale of barbarous treatment, and the episode has formed the basis for a novel by Patrick White, paintings by Sidney Nolan, music by Peter Sculthorpe and several films.

***

By such means the land was taken, settled and possessed. To make it productive and profitable there were the convicts. Between 1821 and 1840, 55,000 convicts landed in New South Wales, and 60,000 in Van Diemen’s Land where transportation continued for a further decade. The great majority were assigned to masters and most served out their time in rural labour. There was keen demand for them since a pastoral station needed large numbers of shepherds, stockmen and hutkeepers, and bond labour could be made to endure the isolation and insecurity that deterred free labour. Convicts, who cost no more than their keep, underwrote the rapid growth and high yields of the pastoral economy.

Assignment was now accompanied by a far tighter regulation. Convicts were no longer allowed free time at the end of the day or permitted to receive ‘indulgences’. As Bigge had recommended, there were fewer pardons and no more land grants to convicts on the expiry of their sentences. Officials exercised a closer control over the treatment of assigned convicts and the magistrates before whom they were brought for breach of the rules. Lieutenant-Governor Arthur in Van Diemen’s Land went furthest in his construction during the 1820s and 1830s of an elaborate system of supervision documented in ‘Black Books’ that set out a full record of every felon’s behaviour ‘from the day of their landing until the period of their emancipation or death’. His regimen was less brutal than that of his predecessors, though one convict in six was still flogged annually, but perhaps more chilling in its bureaucratic regularity. As the convict system was made more regular and its caprices smoothed out, so the opportunities to circumvent its rigours were closed. That made it less, not more, normal.

Those who broke the rules were subjected to further punishment, now carefully graduated in severity: first, flogging or confinement, then consignment to public works or the chain gang, and finally secondary transportation to one of the special penal settlements set well away from civilisation. These settlements multiplied rapidly: Port Macquarie, up the coast from Newcastle, in 1821, and Moreton Bay, further north, in 1824; Macquarie Harbour on the west coast of Van Diemen’s Land in 1822, and Port Arthur, on the southeast corner of the island, from 1832. Norfolk Island was also used for the same purpose from 1825. Such sites were chosen for their isolation, and the natural beauty of the locations only emphasised the horrors attached to their reputations. Macquarie Harbour was approached through a narrow and treacherous entrance, Hell’s Gates, and its inmates had to cut down the giant eucalypts from the rainswept hills and haul them to the water’s edge. Port Arthur, where the stonework still stands in the lush green surrounds of the Tasman Peninsula as a major tourist attraction, has served as a prison, asylum, boys’ prison and, in 1996, the site of a gun massacre.

Moreton Bay, where eventually the city of Brisbane arose, had a death rate of one in ten. Its commander, Captain Patrick Logan, was killed in 1830 by Aborigines at the instigation, it was claimed, of the convicts he mistreated. A popular ballad celebrated the event:

Norfolk Island’s new commander in 1846, John Price, began by hanging a dozen mutineers and was accused by his own chaplain of ‘ferocious severity’ that included chaining men to a wall in spread-eagle position with an iron bit in the mouth. Some years after Price left Norfolk Island to become inspector-general of prisons at Melbourne, a group of men fell on him and beat him to death.

The infamies of Norfolk Island and other penal settlements undoubtedly achieved their deterrent purpose in Britain. Earlier complaints that exile to Botany Bay resulted not in penitence but pleasure were replaced in the 1830s with an image of New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land as sites of close confinement and desperate extremity. This reputation, however, strengthened the hand of the evangelical critics. They publicised the scandals that emerged from the penal settlements to clinch their argument that the convict system was immoral and unnatural. Along with campaigns against slavery and oppression of native peoples in other parts of the Empire, the anti-transportation movement worked on a humanitarian conscience that was more sensitive to pain, more susceptible to reports of moral degradation. It also fostered the pejorative British attitudes towards the Australian colonies that affronted the colonists, and possibly contributed to a lingering condescension: well into the twentieth century a prickly Australian could be accused of ‘rattling his chains’.

Within Australia there was a reluctance to acknowledge the convict stain. The gothic horrors of Macquarie Harbour, Port Arthur and Norfolk Island were lodged subsequently in the popular imagination through the writing of Marcus Clarke (who based a character in the novel His Natural Life, 1874, on Price), William Astley (who wrote of the same events during the 1890s in Tales of the Convict System and Tales of the Isle of Death), and more recently in Robert Hughes’ epic The Fatal Shore. Against such dark and brooding imagery contend the revisionist historians, who point out that most convicts never experienced secondary punishment. Their emphasis on the utility of the convict worker and normality of the convict experience within a comparative framework of global movements of labour in the nineteenth century is now in turn challenged by cultural historians fascinated by the otherness of the convicts. A recent study has noted their ethnic diversity. They came from Antigua and Barbados, China and India, Madagascar and Mauritius; they included Maori warriors and Aboriginal men punished for night raids and pitched battles, bushranging, and even pauperism.

Women, who constituted one-sixth of all the transportees, have particular salience in these reworkings of convict history, because they emerge in them as actors in their own right. Earlier historians assessed the female convicts according to their performance of particular social functions, usually posed in moral or economic terms. Were these women ‘damned whores’ or virtuous mothers, robust human capital or a wasted resource? Given the dual subordination of convict women, to the state and to men, such questions could hardly resolve the contradictions of their condition. The female transportees brought valuable qualities – they were younger, more literate and more skilled than the comparable female population of the British Isles – but had a minor role in the pastoral industry and were usually employed in indoor work. They played a vital demographic role – they were more fertile than those whom they left behind – but the assignment system made it difficult for them to marry.

Mary Sawyer, a female convict in Van Diemen’s Land, applied to marry a free man in 1831. Her record showed a series of misdemeanours – she was insolent, she had absconded, she had been ‘tipsy’ – and she was refused permission to marry until she had been ‘twelve months in service free from offence’. Two years later Sawyer was back in detention. Since the authorities were reluctant to send females to the places of special punishment, there was a heavy reliance on special ‘female factories’ built at Parramatta, Hobart, and then other centres. These served as places of secondary punishment but also as refuges for the unemployed and the pregnant, and provided the women with a space to assert their own rough culture.

The convict system cast a long shadow over societies that were ostensibly moving towards civic normality. In keeping with Bigge’s recommendation that the Australian colonies should be places of free settlement, the British government constrained the governor with a legislative council to authorise his measures and an independent court to ensure that they were not repugnant to English law. The first legislative council was a primitive affair of just seven appointed members, and Macquarie’s immediate successors were slow to grasp that they no longer possessed an absolute authority. In 1826 Governor Ralph Darling altered the sentence of the court against two soldiers who had stolen to obtain a discharge, and ordered that they be worked in chains. The death of one of them brought condemnation of the governor’s actions by the press, which he attempted to suppress with a law that the chief justice disallowed. Several years later, Darling had one newspaper editor imprisoned under new legislation, which the Colonial Office disallowed. Other restrictions included the exclusion of former convicts from jury service, a slight that provoked the emancipist poet Michael Robinson to propose a toast at the Anniversary Day dinner on 26 January 1825, ‘The land, boys, we live in’.

By this time a line of cleavage was apparent between those who wished to preserve political authority and social esteem for the wealthy free settlers and those who sought broader, more inclusive arrangements. The division was no longer simply one between exclusive and emancipist, for a new generation of those born in the colony had come of age – hence the common designation of ‘currency lads and lasses’ (in reference to locally minted money) as opposed to the ‘sterling’ or ‘pure merinos’ (since they flaunted their unsullied pedigrees and pastoral wealth). The most prominent of the currency lads was William Charles Wentworth, the son of a convict mother and highwayman father, who had agreed to come out as a colonial surgeon instead of as a convict, and prospered under Macquarie as a trader, police commissioner and landowner. His son was educated in England and returned in 1824 with a keen resentment of the exclusives after rebuff in a suit for the daughter of John Macarthur. Darling described Wentworth as a ‘vulgar, ill-bred fellow’; he denounced Darling as a martinet.

Through the newspaper he helped establish, the Australian, Wentworth agitated for an extension of freedom, an unfettered press, a more inclusive jury system, a more representative legislature. These objectives were gradually won against the lingering restrictions in a society where so many strangers were suspect – a Bushranging Act introduced in 1830 gave such extraordinary powers of arrest that even the chief justice was apprehended while walking near the Blue Mountains. A partly elected legislature, which was conceded in 1842, had to await the cessation of transportation, for reasons the minister for the colonies made clear: ‘As I contemplate the introduction of free institutions into New South Wales, I am anxious to rid that colony of its penal character.’

More than this, the popular movement that gathered force in the 1830s asserted the equal rights of all colonists, regardless of origin or wealth. It sought to break down the disparities and distortions that pastoralism generated in combination with transportation, and to replace a social hierarchy in which a rich oligopoly controlled land and labour with a more open and inclusive society that would allow all to share in the bounty. Its members styled themselves Australians or natives, and that term signified an attachment to place – the freedom they sought was for the colonisers, not the colonised – but their movement also drew on the growing numbers of new arrivals. From 1831 the British government used revenue from sale of land to subsidise the passage of a new class of ‘free’ migrants seeking a fresh start. They arrived in New South Wales in increasing numbers – 8000 in the 1820s, 30,000 in the 1830s – and chafed at the restrictions they encountered.

The new land laws replaced grants with sale by auction and generated sufficient revenue to finance a substantial scheme of assisted migration. It altered the balance of population movements among the settler societies: whereas in 1831, 98 per cent of emigrants from the British Isles crossed the Atlantic to the United States or Canada, in 1839 a quarter of them chose Australia. A further 80,000 free settlers landed in New South Wales during the 1840s. Sale of land also weakened the arbitrary character of colonial rule, for it replaced the grace-and-favour system of land grants with the impersonal operation of an open market.

The engrossment of land continued, however, because the pastoralists moved beyond the official limits of settlement to occupy their runs by simply squatting on them – that term of disparagement originally applied to former convicts who gleaned a living on ‘waste land’, but it soon came to designate a privileged class of large landholders: the ‘squattocracy’. Bourke’s introduction of pastoral licences in 1836 was followed by further regulations that restricted the tenure of squatters, but the British government set aside this threat to their privileges when, in 1847, it provided fourteen-year leases. A hapless governor who tried to compel the pastoralists to pay for their runs remarked that ‘As well might it be attempted to confine the Arabs of the Desert … as to confine the Graziers or Woolgrowers of New South Wales within any bounds’. With the introduction of leases the squatters legitimated their illegal occupancy and turned possession into property. The buying and selling of land as a freely tradable commodity turbocharged the economies of the settler colonies.

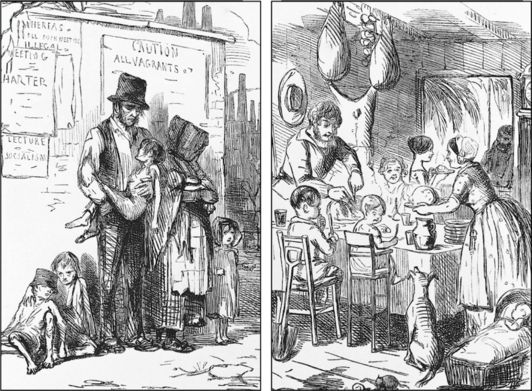

Emigration as a remedy for poverty. In this English celebration of the colonies, the sullen discontent of the poor during the ‘hungry forties’ is contrasted with familial plenty across the seas. The references to Chartism, socialism and legal repression emphasise the contented harmony of colonial life.

The rapid expansion of the frontier made effective supervision of convict assignment increasingly difficult, while the use of land revenue to subsidise migration rendered it increasingly superfluous. By the late 1830s the pressures for the abandonment of penal transportation were thus becoming irresistible. A parliamentary committee in London gathered evidence of the iniquity of the convict system, and its 1837 report deemed transportation an ‘inefficient, cruel and demoralising’ punishment that turned colonists into ‘cruel and hard-hearted slave-owners’. The government suspended transportation to New South Wales in 1840. An attempt to revive it in 1849 brought indignant colonial protest and final abandonment.

That left Van Diemen’s Land as the destination for criminal exiles. The island colony (its administration was separated from New South Wales in 1825) had, in any case, a higher proportion of transportees and a smaller proportion of free settlers: three-quarters of the population in 1840 consisted of convicts, ex-convicts and their offspring. The gap between the exclusive and the felon was wider, more poisonous in its effects. The eagle-eyed Governor Arthur kept a far closer control than his mainland counterparts, extending to a law in 1835 that imposed special penalties on convicts, ticket-of-leave men and even expirees.

The pastoral gentry built country seats of impressive grandeur and planted the amenities and institutions of English landed society, as if to ward off the raw novelty of life on a distant island where the brooding hills and sombre forests pressed in upon them. The finest of all colonial artists, John Glover, built his house on the northeast plain on a property of 3000 hectares. He painted it in 1835 with orderly rows of imported flowers and shrubs in the foreground, the eerie native growth behind. His farm scenes of Arcadian tranquillity reconstructed a familiar English world. Yet the veneer of civilisation was thin and the rapid increase in convict numbers during the 1840s – more than 25,000 were added to a population of fewer than 60,000 – increased the demand to remove the criminal incubus and start anew. With its abandonment of transportation in 1853, Van Diemen’s Land became Tasmania.

John Glover was a successful English artist who settled in Australia in 1831. His 1835 painting A View of the Artist’s House and Garden in Mill Plains, Van Diemen’s Land domesticates the landscape with European plants.

***

One reason for the stagnation of Tasmania during the 1840s was that so many of its enterprising residents crossed Bass Strait for the Port Phillip district on the mainland. While the British government rejected the land grab that John Batman and his colleagues negotiated with the Aboriginals in 1835, it had thrown open the district to settlement. A stream of overlanders who followed Thomas Mitchell’s route from New South Wales quickly joined the over-straiters to spread over the rich grasslands. By 1841 the district contained 20,000 settlers and 1 million sheep, and by 1850 the population reached 75,000 Europeans and 5 million sheep. Land in the principal settlement of Melbourne at the head of Port Phillip Bay was already attracting speculative English investment.

The rectangular grid design of the new town, laid out on Bourke’s instructions in 1837, marked a break with the older settlements of Sydney and Hobart. They were dominated by their garrisons and barracks, an improvised and irregular streetscape marking out the administrative, commercial and residential quarters, with the well-to-do commanding the higher spurs and the lower orders huddled close to the water’s edge. Melbourne, by contrast, was a triumph of utilitarian regularity, a series of straight lines imposed on the ground that allowed investors to buy from the plan.

Two other new settlements used commerce as the basis of colonisation. The first of them, the Swan River Colony, began with an eye to the threat of French occupancy: in 1826 the governor of New South Wales sent a party to King George’s Sound on the far southwest corner of Australia to forestall that possibility and a naval captain, James Stirling, to explore the principal river further up the western coast. The decision in 1829 to annex the western third of Australia and create a colony on the Swan River favoured a group of well-connected promoters who were allocated land in return for their contribution of capital and labour. They created a port settlement, Fremantle, at the mouth of the Swan, and a township, Perth, further up where the river widened, but their hopes of agricultural bounty were soon dashed. By 1832, out of 400,000 hectares that had been alienated just forty were under cultivation.

The failure of the original expectations stemmed partly from the poor soil and dry climate, but most of all from shortage of labour: the 2000 who arrived in the foundation years scarcely increased for a further decade. In 1842 an Anglican clergyman visited one of the colony’s original promoters. His cousin, Robert Peel, had been a minister in the government that authorised the colony and was now the prime minister. Yet Thomas Peel, the proprietor of more than 100,000 hectares, was living in ‘a miserable hut’ with his son, mother-in-law and a black servant. ‘Everything about him shows the broken-down gentleman – clay floors and handsome plate – curtains for doors and piano forte – windows without glass and costly china.’

Such a fate had been predicted by a perceptive, if erratic critic, Edward Gibbon Wakefield, when the Swan River Colony was proposed. Writing in 1829 from Newgate Prison in London (where he was imprisoned for eloping with a young heiress) a work that he passed off as a Letter from Sydney, Wakefield observed that cheap land made labour expensive since the wage-earner could too easily become a proprietor. His own scheme of ‘systematic colonisation’ would set a higher price on land to finance migration and ensure an adequate labour supply – like Bigge, he sought to replicate the British class structure, only he would replace the convict depot with the labour exchange. Land, labour and capital could be combined in proper proportions by providing that settlement was confined and concentrated. ‘Concentration would produce what never did and never can exist without it – Civilization.’

An accomplished mesmerist, Wakefield appealed to both Utilitarians and political economists with his idea of harnessing self-interest and social improvement in model communities created by private initiative with a self-regulating division of labour, generous provision of parks, churches and schools, and the greatest measure of freedom. Systematic colonisation was implemented in six separate New Zealand settlements. It was first attempted in South Australia.

The Province of South Australia, established in 1836, distributed power between the Crown and a board of commissioners responsible for survey and sale of land, and selection and transport of its migrant labour force. While the principal settlement, Adelaide, and its surrounds were carefully laid out by William Light, the surveyor-general, the arrangement soon succumbed to land speculation, and South Australia reverted to the status of an ordinary Crown colony in 1842. It recovered, nevertheless, with fertile wheatlands surrounding the indented coast, and rich copper deposits. By 1850 the white population passed 60,000. The colony fulfilled its founder’s expectations in other ways: it was a free colony, untainted by convicts, and with a measure of self-government; it was familial, with a closer balance of male and female than any other Australian settlement; and it offered religious equality, so that Nonconformist denominations imparted an improving respectability to its public life.

With the British settlement in the central portion of Australia, the whole of the continent was formally taken up. The increase in colonial population – 30,000 in 1820, 60,000 in 1830, 160,000 in 1840, 400,000 in 1850 – reveals a quickening tempo, as does the spread of settlement after 1820 beyond the original narrow enclaves in the southeast. Yet the dispersal remained limited. A Queensland outpost got under way only after the Moreton Bay penal colony was abandoned in 1842 and the district thrown open to settlement; the white population in 1850 was just 8000. Attempts to establish new colonies further north invariably failed, and the white population above the Tropic of Capricorn was negligible. After sixty years of endeavour, two-thirds of the white population still lay within the southeast corner of the mainland. The same proportion has held ever since.

Already 40 per cent of the population lived in towns. The preference for contiguity was a pronounced feature of the older penal settlements and even stronger in the new, voluntary ones. The graziers of New South Wales might roam like the Arabs of the desert, but the less favoured clung to the comforts of the oasis. For all the attempts of the governors after the Bigge report to send convicts up-country, they drifted back to more congenial surrounds such as The Rocks area of inner Sydney with its rough conviviality and networks of support. Isolation in the bush had its own measure of freedom, and generated its own fraternity of mateship, but isolation reduced choice and increased exposure. Life in The Rocks was rowdy and violent, most children were born out of wedlock and there was a constant turnover of residents, but this very fluidity shielded the inhabitants from surveillance and control. In the free colonies a different logic produced a similar result. There was no desire for anonymity here but rather a hunger for sociability that would soften the emotional rigours of separation and ease loneliness. A fabric of voluntary associations – civic, religious and recreational – was quickly created in Adelaide, Melbourne and Perth to incorporate their residents into community life.

In the penal colonies such institutions were more likely to be imposed from above. For as long as the convict system lasted these colonies had to be administered because they could not be trusted to govern themselves, and those who were subjected to such control were less inclined to submit themselves willingly to its operation. In the absence of representative assemblies, people turned for protection from over-zealous officialdom to the courts, so that political debate was displaced into arguments over legal rights. The custodians tried persistently to civilise these colonies and plant the institutions that would redeem their inhabitants, yet every one of the civilising devices they employed was distorted by the coercive purpose to which it was put.

The family was one such device. In 1841 Caroline Chisholm, the wife of an army officer, established a female immigrants’ home in Sydney to rescue single women from the mortal sin to which they were so perilously exposed. She accompanied them into rural areas and placed them in domestic employment under suitable masters in the hope that matrimony would follow. To end the ‘monstrous disparity’ between the sexes and rescue the colonies from ‘the demoralising state of bachelorism’ was her aim, so that ‘civilization and religion will advance, until the spire of the churches will guide the stranger from hamlet to hamlet, and the shepherds’ huts become homes for happy men and virtuous women’. In this scheme of ‘family colonisation’ the women were to serve the men as wives and mothers in order to reclaim them to Christian virtue; as she put it, they were pressed into service as ‘God’s police’.

Religious worship was in turn promoted in New South Wales by the Church Act of 1836, which subsidised the building of churches and the stipends of ministers. Similar legislation was extended to Van Diemen’s Land in the following year. The measure was significant for its recognition of all denominations (it was less than a decade since Catholics in the United Kingdom had been allowed to participate in public life), and confirmation of religious freedom. It brought a rapid growth of church activity, and the fact that Methodists, Congregationalists and Baptists used that term in preference to the more traditional ‘chapel’ declared their claims to parity. There would be no confessional state in Australia, nor the customs and traditions that shaped community life in Europe. Here religion was more institutional and faith a matter of personal belief and commitment.

In 1848 a minister in New South Wales reported the saying ‘No Sunday beyond the mountains’; it was used, he said, by men as they descended from the Blue Mountains onto the western plains. Yet provision for worship had increased five-fold since the introduction of public subsidies. Often it meant no more than a small timber box on the main street of an infant settlement, or a primitive church built of slabs in a freshly cleared paddock where tree-stumps outnumbered gravestones. The church brought people together in common purpose and encouraged a range of voluntary activity.

Public assistance also encouraged denominational rivalries. While the Church of England made the most of the subsidies, since it could draw on support of wealthy adherents to qualify for them, the local hierarchy was reluctant to accept its loss of privileged status. The Anglicans continued to think of themselves as the church of the establishment, with the strengths and weaknesses of that orientation. Catholics remained sensitive to slights, a feeling intensified by their status as both a religious and a national minority that was over-represented among the needy. The English Benedictine who was sent as vicar-general in 1832 wrestled with the Irish temper of his charges, but his attempt to recruit English priests failed. Without priests there could be no sacraments, and the inability to sustain the faith exacerbated resentment. John Dunmore Lang, the leading Presbyterian minister, was an implacable foe of both the episcopal denominations but particularly hostile towards Catholicism. Others who shared his vision of a godly nation also tried to impose a civic Protestantism on public life.

In this formative period the churches also worked out their local forms of government, and the patterns of support. The Anglicans had most adherents, something less than half, followed by the Catholics, about a quarter. Presbyterians, Methodists, and other Nonconformists made up the remainder. Though there were significant variations between the colonies, these proportions would persist for at least a century. The growth of Christian worship came from a low base. Anglican, Catholic and Presbyterian alike complained of the neglect of the Sabbath, the profanity, and immorality, and shared with the less numerous Nonconformist evangelicals a preoccupation with sin. Alongside the ballads and broadsides that proclaimed defiance of conventional morality –

– there were some contrite convict statements. Typically composed in narrative form as moral tracts, these confessional works described the wretched degradation of penal life, told of the blessed moment when the sinner became conscious of God’s grace, then recorded the good works and purposeful endeavour that brought sobriety, industry, and happiness after the convert put aside vicious habits and dissolute associations. Such homilies only emphasised the heathen character of the mass of the felonry.

The colonists drew also on the arts of civilisation. In prose and verse, art and architecture, they marked the course of progress, order and prosperity. Landscape painting contrasted the primitive savage with the industrious swain, the sublime beauty of nature with the divided fields and picturesque country house. Didactic and epic odes celebrated the successful transformation of wilderness into commercial harmony:

The imagery was neoclassical, casting back to the ancient civilisations to affirm the course of empire and suggesting how through successful imitation the colonists were participating in universal laws of human history to fulfil their destiny. Hence Wentworth’s ‘Australasia’, submitted for a poetry prize while he was a student in Cambridge in 1823:

The neoclassical sought to affirm and renew a received model of social order that was organic and hierarchical. Through restraint and regularity it endeavoured to dignify the harsh circumstances of involuntary exile and brutal conquest, to elevate colonial life, and instruct the colonists in the arts and sciences. As the coercive phase of the penal foundations gave way to emancipation and free settlement, the neoclassical model yielded to the Utilitarian project of moral enlightenment. The emphasis here was on schemes of secular as well as spiritual improvement, temperance, rational recreation, cultivation of the mind and the body. It found expression in the pastoral romance of the bush, where the merry squatter achieved freedom and fulfilment in a way of life that was no longer imitative but distinctive and new.

The very names that the settlers placed on the land suggest a similar emergence of new from old. The principal settlements were named after members of the British government (Sydney, Hobart, Melbourne, Brisbane, Bathurst, Goulburn) or birthplace (Perth) or royal birthplace (Launceston) or consort (Adelaide). Harbours and ports were more likely to honour local figures (Port Macquarie, Darling Harbour, Port Phillip, Fremantle). Familiar names were transferred to some localities (the Domain, Glebe), some were simply descriptive (The Rocks, the Cowpastures, the Cascades, the Swan River) and some evocative (Encounter Bay) or associational (Newcastle). There were few Aboriginal names in the early years of settlement (Parramatta, Woolloomooloo, though Phillip named Manly after one) but they were more common by the 1830s (Myall Creek). By then the obsequious habit was in decline. Rather than seek favour with official patrons in London, the locals proclaimed their places of origin. Hence the regional clusters of English, Scottish, Irish, Welsh and, from the 1840s, even German place-names.

These ethnic identities found their way into work and worship. The maintenance of networks, the searching out of compatriots and the reproduction of customs were a natural response to the anonymities of resettlement. With some outlying exceptions (such as the German Lutheran community in the Barossa Valley of South Australia), however, none of the national groupings formed a genuine enclave. All of them were porous, allowing for movement, interaction and intermarriage. The display of Cornishness, for example, was more the advertisement of particular qualities and attributes well suited to work in the copper mines of South Australia than of any irredentist impulse. The ersatz Scottishness that compounded Burns suppers and Highland games was a secondary identity for those who chose to practise it. A Saint Patrick’s Day procession through the streets of Sydney began in 1840, not as a protest but ‘to demonstrate the respectability, loyalty and community spirit of affluent Irish emancipists’.

The same impulse was apparent in the commercial centres of the new colonies, where land was bought and sold, and the owner built as he chose. The symmetrical balance of Georgian and Regency design used, with local adaptations, in Sydney and Hobart, succumbed in Melbourne and Adelaide to a multiplicity of styles – medieval Gothic, renaissance revival and the round-arched Italianate – which proclaimed the new measure of civic freedom and autonomous identity.

Between 1822 and 1850 the Australian colonies relaxed coercion by the state for reliance on the market and its associated forms of voluntary behaviour. The transition was accompanied by violent expropriation, and the convict experience left its own legacy of bitter memories. Yet the outcome was a settler society characterised by high rates of literacy, general familiarity with commodities, productive innovation, and impressive adaptation to the challenge of uprooting and starting anew. What began as a place of exile had become a location of choice.