At the end of 1850 Edward Hargraves returned to Sydney from a year on the other side of the Pacific. He was one of the ‘fortyniners’ who had converged on California in search of gold. Although unsuccessful in that quest, Hargraves was struck by the similarity between the gold country there and the transalpine slopes of his homeland. In the summer of 1851 he crossed the Blue Mountains to Bathurst and washed a deposit of sand and gravel from a waterhole to disclose a grain of gold in a tin dish. ‘This is a memorable day in the history of New South Wales’, he told his companion. ‘I shall be a baronet, you will be knighted, and my old horse will be stuffed, put into a glass-case, and sent to the British Museum.’ Hargraves named his place of discovery Ophir and set off back to Sydney to claim a reward from the governor.

Hargraves was not the last Australian miner to engage in self-promotion or seek public recognition and reward. He was not even the first colonist to find gold: shepherds had picked up nuggets from rocky outcrops, and a clerical geologist collected many such specimens. In 1844 this scientist showed one to Governor Gipps and claimed that he was advised, ‘Put it away, Mr Clarke, or we shall all have our throats cut.’ This again was one of the tall tales spun from the precious metal. The colonial authorities were certainly worried that buried treasure would excite the passions of the criminal class and distract men from honest labour. Faced with the fact of a local rush, however – and within four months of Hargraves trumpeting his success, one thousand prospectors were camped on Ophir – they devised an appropriate response. There would be commissioners to regulate the diggings and collect licence fees, which entitled the holder to work a small claim. The same pragmatic policy was extended to the Port Phillip District (which in July 1851 was separated from New South Wales and renamed the colony of Victoria) when the rush spread there three months later.

The deposits of gold in southeast Australia were formed by rivers and creeks that flowed down the Great Dividing Range and left large concentrations of the heavy sediment in gullies as they slowed where the gradient flattened. Much of this gold was close to the surface and could be dug with pick and shovel, washed in pans or simple rocking cradles. Together with the licence system, the alluvial nature of the goldfields allowed large numbers to share in the wealth. There were 20,000 on the Victorian diggings by the end of 1851, and their population peaked at 150,000 in 1858. The diggers worked in small groups, for the surface area of a claim was often no larger than a boxing ring, and moved on as soon as they had exhausted the ground below.

During the 1850s Victoria contributed more than one-third of the world’s gold output. With California it produced such wealth that the United States of America and the United Kingdom were able to back the expansion of their monetary systems with gold to underwrite financial dominance. The gold rush transformed the Australian colonies. In just two years the number of new arrivals was greater than the number of convicts who had landed in the previous seventy years. The non-Aboriginal population trebled, from 430,000 in 1851 to 1,150,000 in 1861; that of Victoria grew sevenfold, from 77,000 to 540,000, giving it a numerical supremacy over New South Wales that it retained to the end of the century. The millions of pounds of gold bullion that were shipped to London each year brought a flow of imports (in the early 1850s Australia bought 15 per cent of all British exports) and reinforced the proclivity for consumption. The goldfields towns also provided a ready market for local produce and manufactures. In this decade the first railways were constructed, the first telegraphs began operating and the first steamships plied between Europe and Australia.

‘This convulsion has unfixed everything,’ wrote Catherine Spence, an earnest young Scottish settler in Adelaide when she visited Melbourne at the height of the ‘gold fever’. ‘Religion is neglected, education despised, the libraries are almost deserted; … everybody is engrossed by the simple object of making money in a very short time.’ Many shared her concern. Gold acted as a magnet for adventurers from all round the world, with a preponderance of single men who imbued the diggings with masculine excitement. Most of them were British but there was a substantial proportion of ‘foreigners’: Americans, with a knowledge of water-races and a fondness for firearms; French, Italian, German, Polish and Hungarian exiles who had been swept up in the republican uprising of 1848 that shook the thrones of Europe. The Chinese, 40,000 of them, made up the largest foreign contingent and were subjected to ugly outbreaks of racial violence.

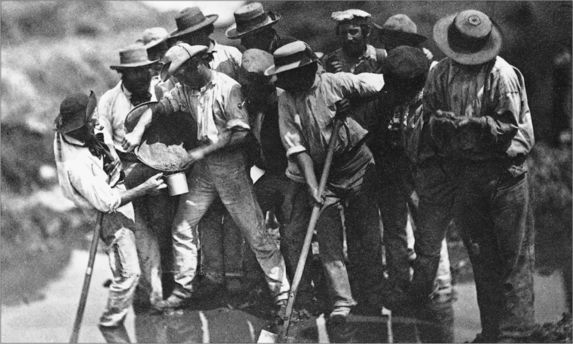

The writer and photographer Antoine Fauchery worked for two years on the Victorian fields in the early 1850s. His carefully composed tableau of alluvial prospectors, with shovels and pan, conveys the excitement of the early gold rush.

At the head of Port Phillip Bay, where most goldseekers disembarked, heaps of abandoned possessions alongside the forest of masts testified to the exorbitant prices for accommodation and transport. Seamen jumped their ships, shepherds left their flocks, servants quit their masters and husbands their wives to seek fortunes with pick and shovel. Small wonder that critics saw the gold rush as a ruinous inundation and denounced the mania that turned settlers into wanderers, communities into mobs.

These fears came to a head as the surface gold at Ballarat was worked out and the diggers, who now had to labour for months in wet clay to reach the deep leads, became resentful of the bullying and corruption associated with the collection of the monthly licence fee. Agitators such as the Prussian republican Frederick Vern, the fiery Italian redshirt Raffaelo Carboni, and the blunt Scottish Chartist Tom Kennedy, harangued them:

They came together in a Reform League under the leadership of an Irish engineer, Peter Lalor, to declare that ‘the people are the only legitimate source of all political power’. At the end of 1854 a thousand men assembled at Eureka, on the outskirts of Ballarat, and unfurled their flag, a white cross and stars on a blue field, to proclaim their oath: ‘We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties.’

Troops from Melbourne overran the improvised stockade on the slopes of the Eureka goldfield and killed twenty-two of its defenders. But the rebels were vindicated. Juries in Melbourne refused to convict the leaders put on trial for high treason; a royal commission condemned the goldfields administration; the miners’ grievances were remedied and even their demands for political representation were soon conceded, so that within a year the rebel Lalor became a member of parliament and eventually a minister of the Crown.

The Eureka rebellion became a formative event in the national mythology, the Southern Cross a symbol of freedom and independence. Radical nationalists celebrated it as a democratic uprising against imperial authority and the first great event in the emergence of the labour movement. The Communist Party’s Eureka Youth League invoked this legacy in the 1940s, and the industrial rebels of the Builders’ Labourers Federation adopted the Eureka flag in the 1970s; but so did the right-wing National Front, while revisionist historians have argued that the rebellion should be seen as a tax revolt by small business. More recently, the open-air museum at Ballarat has recreated ‘Blood on the Southern Cross’ as a sound-and-light entertainment for tourists.

Rebellion might be too strong a term for a localised act of defiance. Like the officials who overreacted, its celebrants saw it as a belated counterpart to the Declaration of Independence of the American colonists eighty years earlier, without which a transition to nationhood was incomplete. Even a conservative historian writing in the early years of the Australian Commonwealth called it ‘our own little rebellion’. Long before then, however, the Southern Cross had been hoisted anew as an emblem of protest, the Eureka legend incorporated into radical action.

The Victorian gold rush was followed by subsequent discoveries and further rushes. Forty thousand headed for the South Island of New Zealand in the early 1860s, and as many more crossed into New South Wales when fresh finds occurred there. Next came major discoveries up in Queensland, including Charters Towers in 1871, the Palmer River in 1873 and Mount Morgan in 1883, and over the Coral Sea into the Pacific islands. Then there was a movement into the dry Pilbara country of north-western Australia and further south on the Nullarbor Plain, where major finds at Coolgardie in 1892 and Kalgoorlie 1893 completed an anti-clockwise gold circuit of the continent. Meanwhile, in 1883, rich lodes of silver and lead had been found inside the circle by Charles Rasp, a sickly German boundary rider, on a pastoral station in far western New South Wales that became the mining town of Broken Hill; he died a rich man.

The mineral trail was marked by land stripped bare of trees to line the workings and fuel the pumps and batteries, by polluted waterways, heaps of ransacked earth and deposits of mercury and arsenic – and also by churches, schools, libraries, galleries, houses and gardens. The impulse to atomistic and single-minded cupidity that dismayed Spence when the hunt for gold began was quickly tempered by collective endeavour and civic improvement. The repeated movements drew on an accumulation of knowledge and skill, though in the process there was a perceptible change. Later mining fields offered more limited opportunities close to the surface. Their greatest wealth lay deeper in reefs that required expensive machinery and more complex metallurgical processes. So the lonely prospector gave way to the mining engineer, the independent digger to the joint-stock company and wage labour.

Mining communities are always beset by a consciousness of impermanence that is inherent in their dependence on a non-renewable resource. The transformation of the gold rush into an industry created nostalgia for a past heroic era. It was captured in 1889 by a young poet, Henry Lawson, who had grown up on the diggings:

The mateship of the roaring days was kept alive in sentiment and action. The goldfields were the migrant reception centres of the nineteenth century, the crucibles of nationalism and xenophobia, the nurseries of artists, singers and writers as well as mining engineers and business magnates. The country’s great national union of bush workers had its origins on the Victorian goldfields. Its founder was William Guthrie Spence, as earnest and improving as his compatriot and namesake who had lamented the gold frenzy.

***

The gold rush coincided with the advent of self-government. In 1842 Britain granted New South Wales a partly elected legislative council, a concession it extended to South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria by 1851 when the last of these colonies was separated from New South Wales. In 1852, as ships laden with passengers and goods departed British ports for Australia on a daily basis, the minister for the colonies announced that it had ‘become more urgently necessary than heretofore to place full powers of self-government in the hands of a people thus advanced in wealth and prosperity’. He therefore invited the colonial legislatures to draft constitutions for representative government, and in the following year his successor allowed that these could provide for parliamentary control of the administration under the Westminster system of responsible government.

The colonies proceeded accordingly, and in 1855 the British parliament enacted the constitutions of New South Wales, Tasmania and Victoria. South Australia received its constitution in 1856 and Queensland was separated from New South Wales in 1859 and similarly endowed. Henceforth the colonies enjoyed self-government along the lines of the British constitution: the governors became local constitutional monarchs, formal heads of state who acted on the advice of ministers who in turn were members of, and accountable to, representative parliaments. The imperial government retained substantial powers, however. It continued to exercise control of external relations. It appointed the governor and issued him instructions. Any colonial law could be disallowed in London and governors were to refer to the Colonial Office any measure that touched the imperial interest, such as trade and shipping, or threatened imperial uniformity, such as marriage and divorce.

These restrictions were of less immediate concern to the colonists than the composition of their parliaments. Following the British model of the Commons and the Lords, they were to consist of two chambers: an Assembly and a Council. The Assembly would be the popular chamber, elected on a wide masculine franchise. South Australia provided at the outset that all men could vote for the Assembly and the other colonies followed in the next few years. The Council was to be the house of review and a bulwark against excessive democracy.

But how? Those who feared unfettered majority rule favoured the installation of a colonial nobility, a device mooted earlier in Canada and now proposed for New South Wales by the ageing William Wentworth with support from a son of John Macarthur, but ridiculed by a fervent young radical, Daniel Deniehy. Since Australians could not aspire to the ‘miserable and effete dignity of the worn-out grandees of continental Europe’, this ‘Boy Orator’ supposed that it would be consistent with ‘the remarkable contrariety which existed at the Antipodes’ that it should be favoured with a ‘bunyip aristocracy’ – the bunyip being a mythical monster. As for John Macarthur’s son, Deniehy proposed that he must surely become an earl and his coat of arms would sport a rum keg on a green field.

Deniehy’s mockery helped defeat the proposal. New South Wales and Queensland fell back on an upper house consisting of members appointed for life by the governor. As the governor acted on the advice of his ministers, this proved a less reliable conservative brake than was created in South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria, where the upper house was elected on a property franchise. Since those Councils had to agree to any change to their unrepresentative composition, they proved impregnable to the popular will. Furthermore, since the constitutions gave the Councils near equality with the Assemblies in the legislative process (in contrast to Westminster, where the relationship between the two houses of parliament was tilting in favour of the representative branch of the legislature), the men of property were able to veto any popular measure that threatened their interests.

The frequent legislative deadlocks produced occasional but grave constitutional crises, notably in Victoria where advanced liberals mobilised widespread support for reform in the 1860s and again in the late 1870s. The insistence of the Colonial Office that the governor maintain strict neutrality in the first of these confrontations strained the limits of self-government. George Higinbotham, the unbending champion of the colonial liberals, asserted that the governor was bound to take the advice of his ministers and claimed that the instructions of the Colonial Office meant that ‘the million and a half of Englishmen who inhabit these colonies, and who during the last fifteen years have believed that they possessed self-government, have really been governed during the whole of that time by a person named Rogers’, Sir Frederic Rogers being the permanent head of the Colonial Office. Since lesser men shrank from the consequences of Higinbotham’s obduracy, his efforts to put an ‘early and final stop to the unlawful interference of the Imperial government in the domestic affairs of this colony’ were unavailing.

These flaws were obscured in the first, heady phase of self-government by the rapid advance of democracy. In the 1840s a popular movement had formed in Britain around democratic principles embodied in a People’s Charter. Chartism terrified that country’s rulers and many Chartists were transported to Australia. Yet in the 1850s four of the six demands of the Chartists were secured in the three most populous southeastern colonies. Their Assemblies were elected by all men, in secret ballots, in roughly equal electorates, and with no property qualification for members. While the fifth Chartist objective of annual elections found little support, most colonies voted every three years, and by 1870 Victoria embraced the sixth demand, payment of members.

The people governed, and yet they remained dissatisfied with the results, for in their triumph they had created a new tribulation – the popular politician. As their representative he was expected to serve them, and constituents importuned their local member to make the government meet their needs. They demanded roads, railways and jobs for their boys. The member of parliament in turn pressed these claims upon the ministry and, if they were not satisfied, sought to install a more amenable alternative. Under such pressures democratic politics was bedevilled by patronage and jobbery. Elections took on the nature of auctions in which candidates outbid each other with inflated promises. Ministries formed and dissolved in quick succession as the result of shifting factional allegiances. Parliamentary proceedings became notorious for acrimony and opportunism. Public life was punctuated by revelations of corruption, vitiated by cynicism.

Colonial politics, then, operated as a form of ventriloquism whereby the politician spoke for the people. Those who made a career from this activity were artful, theatrical and above all resilient – none more so than Henry Parkes, five times premier of New South Wales between 1872 and 1891, who had arrived as a young English radical and ended as the arch-opportunist ‘Sir ’Enery’, several times bankrupt and a father once more at the age of seventy-seven. If, in principle, the system of government was democratic and the parliamentarians were servants of the people, then the working of the representative institutions left a gulf between the state and its subjects. The politicians shouldered the blame for this unpalatable paradox and Australians quickly developed a resentment of the inescapable necessity of politics. They erected grandiose parliamentary buildings to express their civic aspirations and despised the flatterers and dissemblers they installed there.

The colonial state grew rapidly. In the 1850s it inherited a restricted administrative apparatus of officials, courts, magistrates and local police, which proved quite inadequate for the fresh demands created by the gold rush, and was almost immediately expected to perform important new functions. In addition to the maintenance of law and order, colonial governments embarked on major investment in railways, telegraphic and postal communications, schools, urban services and other amenities. They continued to spend heavily on assisted immigration. They employed one in ten of the workforce, and their share of colonial expenditure rose from 10 per cent in 1850 to 17 per cent by 1890.

The public provision of utilities, in striking contrast to the pattern of private enterprise in the United States, is held up as an exemplar of national difference between dependence on the state and entrepreneurial initiative. The circumstances that confronted the Australian colonies allowed no alternative. They sought to develop a harsher, more thinly populated land by creating the infrastructure for the production of export commodities. The colonial governments alone could raise the capital, by public borrowing on the London money market, and alone could operate these large undertakings. More than this, they were expected to foster development in all its publicly recognised forms – economic, social, cultural and moral – for this was an age that believed in progress as both destiny and duty.

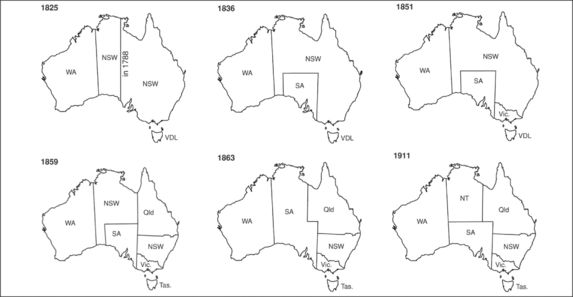

The enhanced role of the colonial state had further effects. When the colonies took charge of their own affairs, they became competitors for immigration and investment. The separation of Queensland from New South Wales in 1859, followed by boundary adjustments in 1861 and the allocation of the Northern Territory to South Australia in 1863, completed the parcelling up of the continent. Except for the transfer of the Northern Territory to a new federal government and the excision of the Australian Capital Territory in 1911, these divisions have remained. The devolution made for important differences in public policy (symbolised by the adoption of different railway gauges) and accentuated regional variations of economy and demography, though a common constitutional, legal and administrative heritage was always apparent.

Self-government also created highly centralised polities. The colonies had previously followed the English practice of appointing local magistrates to conduct local courts, supervise the police, grant licences to publicans, control public works and generally act as the eyes and ears of the administration. Local school boards were responsible for the provision of education. Now these activities were turned over to centralised agencies and funded by colonial revenue rather than from rates. Local initiative languished. Although urban and rural authorities were established on an elective basis, they were mere statutory creations of the colonial legislatures, so that local government remained a stunted creature with residual responsibilities. The police station, the courthouse, the post office and the school, all were agencies of a bureaucratic hierarchy controlled from the capital city by regulation and inspection, post and telegraph, in a career structure that ensured uniformity.

***

The issue that dominated the first colonial parliaments and animated colonial politics was the campaign to unlock the lands. The former Chartists who flocked to the goldfields brought with them a hunger for the freedom and independence of an agricultural smallholding, as did Irish tenants, Americans seized with the doctrines of Jeffersonian democracy, and other Europeans with memories of rural communities broken up by commercial landlords. Those who came to Australia found that its fertile southeast corner was occupied by several thousand pastoralists who were meanwhile entrenching their privileges in the unrepresentative upper houses of the colonial parliaments. The campaign to gain access to the land was therefore simultaneously a campaign to democratise the constitutions.

In Victoria a Land Convention formed in 1857, under a banner with the motto vox populi inscribed on a Southern Cross, to protest against a bill that would renew the tenure of the squatters. In 1858, when the Council rejected electoral reform, the Convention assembled a crowd of 20,000 to march on Parliament House and nail to it a sign, ‘To let, the upper portion of this house’. In New South Wales the Council’s rejection of a land reform proposal provided the Liberal premier with the justification to purge that nominee chamber of its diehard conservatives.

If the land campaign was a source of contention and a means of confronting the inequality of wealth and power, it was inspired by a dream of agrarian harmony.

The land reformers envisaged a society of self-sufficient producers that would channel the energies of the people into productive contentment. It would replace the vast tracts of grassland with crops and gardens, the squalid huts of the shepherds with smiling homesteads, the restlessness of the single man with the satisfactions of family life, the improvised pleasures of the bush shanty with the amenities of civilisation. The yeoman ideal that exerted a powerful influence from this time until well into the next century was an essentially masculine one. It anticipated what a liberal newspaper described in 1856 as a ‘pleasant, patriarchal domesticity’ with the patriarch ‘digging in his garden, feeding his poultry, milking his cow, teaching his children’. That his wife was likely to undertake most of these tasks was passed over. Having acquired the right to govern the state, men assumed equal rights to govern their families.

Selection Acts were passed in all colonies, beginning with Victoria in 1860 and New South Wales in 1861. They provided for selectors to purchase cheaply up to 250 hectares of vacant Crown land or portions of runs held by pastoral leaseholders. Their immediate effect was the opposite of that intended by the land reformers. Squatters kept the best parts of their runs, either by buying them or using dummy agents to select them on their behalf. By the time the loopholes in the early legislation – some of them the result of bribery and some inadvertent – were closed, the squatters had become permanent landowners. The genuine selectors, meanwhile, struggled to earn a living as farmers on holdings that were often unsuited to agriculture. Lack of expertise, shortage of capital and equipment, and inadequate transport defeated many of them.

Those who survived found the yeoman ideal of self-sufficiency turned women and children into unpaid drudges who worked long hours in primitive conditions and subsisted on a restricted diet. A selection had to be cleared by axe, the felled trees cut up and stacked around tree-stumps so that they could be burnt; then it had to fenced, ploughed and put under crop. The need to supplement income with wage labour took men from their homes, separated families and delayed the development of their farms. The father of the bush poet Henry Lawson took up a selection, but his mother worked it, and he wrote of

Land where gaunt and haggard women live alone and work like men

Till their husbands, gone a-droving, will return to them again.

Perhaps half of the selectors gave up the unequal struggle. The remainder persisted, adapted and survived. The family farm became one of Australia’s most resilient institutions.

A revival of bushranging in the 1860s drew on the discontent of the rural poor, and the young men who joined Ned Kelly, the most legendary bushranger of them all, were sons of struggling or unsuccessful selectors. The Kelly gang cultivated local celebrity in the rugged country of northeast Victoria as flash larrikins who stole horses as casually and as recklessly as latter-day delinquents steal cars – until in 1878 they ambushed a police patrol and killed three officers. The gang’s subsequent exploits were the stuff of legend: a series of audacious bank robberies; a long statement of self-justification that joined the ancestral memories of Ned’s Irish convict father to the grievances of an oppressed rural underclass; the beating of ploughshares into body-armour for a final shootout when the gang sought to wreck a train carrying police from Melbourne; and then Ned’s studied defiance through his trial and passage to the gallows. His supposed final words, ‘Such is life’, ensured immortality.

Just as the Kelly gang sang the ballads that commemorated earlier gallant bushrangers, so they too became folk heroes. Sympathisers sustained them in mountain hideouts beyond the reach of the railway, local informers operated a bush telegraph by word of mouth to set against the electronic telegraph of the authorities. More than this, the symbolism of making agricultural implements into helmets and breastplates proved irresistible to journalists and press photographers who carried the story to a national audience, as well as to the writers, artists, dramatists and film-makers who have repeatedly reworked it. Vicious killer or social rebel, Ned Kelly is a product of a countryside on the cusp of modernity.

Those selectors who prospered did so as commercial producers who bought additional land, hired extra labour and combined farming with grazing. Agricultural success came first in the 1870s among wheatgrowers of South Australia and western Victoria, where the advent of the railway and adoption of farm machinery made for productive efficiency. Other farms were hacked out of the dense rainforests along the eastern coast: those in the south used the cream separator and refrigerator to establish a dairy industry, while in the north a thriving sugar industry emerged on plantations. The area of cultivated land increased from less than 200,000 hectares in 1850 to more than 2 million by the end of the 1880s.

Wool production also increased tenfold, and from a much larger base. By the early 1870s it once more led gold as the country’s leading export, and sales to Britain during the 1880s amounted to one-tenth of the national product. The increased output was facilitated by substantial investment in improvements, which in turn was made possible by the newly secured property rights. Larger sheep with heavier and finer fleeces grazed on better pastures that were now fenced and watered by dams and underground bores. Before 1850 a traveller could have proceeded through the pastoral crescent of eastern Australia without opening a gate. Now lines of posts spanned with fencing wire marked the grazier’s transition from squatter to landowner. The enclosed paddocks were dotted with the ghostly trunks and limbs of trees devoid of leaves, killed by ringbarking to augment the pasture; the native wildlife was losing out to imported flora and fauna such as thistles and rabbits, which would become serious pests.

For the time being, the owner rejoiced in the remaking of the habitat. His simple homestead was replaced by a grand residence and probably a townhouse in the capital city where he educated his children and spent part of the year. Architects assisted him to proclaim his success in a sprawling vernacular form or an opulent reproduction of the baronial style, and decorators filled it with art and furnishings from the old country. Behind this imposing edifice were the manager’s quarters, and a small village of workshops, yards, dams, gardens and accommodation for the workforce as well as the woolshed – misleadingly named, for it was a great hall with stands for fifty shearers or more to strip the fleece that afforded these wool-kings their dynastic comforts.

Wool prices remained high until the mid-1870s and then turned down. Caught in a cost-price squeeze, the graziers responded by increasing production, pushing further inland into the arid grassland and saltbush and mulga country beyond. Abandoned properties testified to the perils of excessive optimism. Newcomers pressed too far into Queensland in the 1860s, too far north in South Australia in the 1870s, and too far west in New South Wales in the 1880s. These advances ended in retreat. Cattle could survive in the low-rainfall zone – they could walk further to water, were less vulnerable to attack by dingo, and could be driven long distances to market – but they were less profitable since experiments with canning and refrigeration had yet to succeed, and beef producers were still restricted to the domestic market.

The movement into the interior brought a revival of exploration and yielded new heroes in a more grandiose, high-Victorian mode of epic tragedy. In 1848 the German Ludwig Leichhardt, famous for an earlier overland journey to the Northern Territory, set off for the west coast from Queensland and disappeared with six companions; among the conjectures of his fate in the wilderness is Patrick White’s novel Voss (1957). In the same year Aborigines speared another explorer, Edmund Kennedy, in the far-north Cape York Peninsula.

In 1860 Robert Burke, an officer on the Victorian goldfields, and William Wills, a surveyor, were seen off at Melbourne on a lavishly appointed expedition to cross the continent from south to north. Scattering equipment behind them, they reached the muddy flats of the Gulf of Carpentaria but died of starvation on the return journey at Coopers Creek, near the border of Queensland and South Australia. The colonists made heroes of them in verse and art, and there have since been histories, novels, plays and several films. Their remains were brought back to Melbourne to lie in state before a funeral that attracted more than 50,000 mourners. The pencilled diary of their final days holds pride of place in Victoria’s state library. A statue was unveiled in Melbourne in 1865, the first great monument to inhabitants of that city; its repeated relocation attests to an uncompleted journey.

It was a South Australian, John Stuart, who succeeded in the following year and his return journey was a near-run thing, with partial paralysis and temporary blindness – but unlike Burke and Wills, whose bodies were recovered for a state funeral, Stuart left Australia embittered at the lack of recognition. His journey provided the route for the Overland Telegraph line, completed in 1872, which established direct electronic communication from Europe; the repeater stations became bases for prospectors and pastoral pioneers in Central Australia. Further expeditions traversed the Gibson Desert to the west and the Nullarbor Plain that stretched between Adelaide and Perth. Alexander Forrest’s journey from the north coast of Western Australia to the Overland Telegraph found grazing lands in the Kimberley district that were taken up in the 1880s by overlanders from Queensland such as the Durack family.

Another South Australian explorer in the spinifex country of the western desert crested a hill some 300 kilometres from the Overland Telegraph in 1873 and saw a great monolith more than 2 kilometres long and 350 metres high. The explorer named it Ayers Rock, after the colony’s premier. In 1988 it was returned to the traditional owners and its original name of Uluru was restored. Red in colour, it transmits a spectacular light at sunrise and sunset. For its owners it is a sacred place, and for the many tourists who now flock to Uluru and the New Age visitors who journey there as a spiritual pilgrimage, it is the epicentre of the country’s Red Heart. It is also a place of mystery and dark secrets. The disappearance there in 1980 of a baby, Azaria Chamberlain, joined the powerful tradition of the child lost in the bush to rumours of devil worship and ritual sacrifice at a site of sinister mystery.

These are recent transformations. Earlier European Australians spoke not of a Red Centre but a Dead Centre. The inland frontier of settlement was known as the ‘the outback’ or the ‘Never-Never’, a place of confrontation with inhospitable nature. In 1891, the year before he hanged himself with his stockwhip, the drover and poet Barcroft Boake wrote of the city comforts provided to absentee pastoralists by the men and women of the outback:

In contrast to the westward occupation of North America, the European occupation of Australia was never completed, the inland frontier never closed.

As they moved north, the Europeans encountered further challenges. Geographically, the upper third of the Australian continent above the Tropic of Capricorn presents extreme variations of landforms, rainfall and habitat: from the arid northwest coast, across stretches of red sand dunes, claypans, baked floodplains and broken, rocky country to the dense rainforests, mangrove beaches and coral reef that run along the eastern shore. Physically, the region called into question the coloniser’s capacity to adapt: habituated to a temperate climate, newcomers were slow to shed their flannel underwear, Crimean shirts and moleskin trousers, or give up their diet of meat, flour and alcohol. Psychologically, it confronted them with the presence of other people more at home in an alien environment. On both sides of the Torres Strait and Coral Sea, where European Australia converged with Asia and the Pacific, the white man was outnumbered.

Apart from the Aboriginal people of the north, Malays, Filipinos and Japanese worked in the pearling industry on the northern coast, and Afghan cameleers carried goods to mining camps. The Chinese were the most numerous and encountered the greatest hostility. For more than a century they were the largest non-European ethnic group in Australia, different in appearance, language, religion and customs. Nearly 100,000 came to Australia during the second half of the nineteenth century as part of a much larger movement that encompassed the Pacific Rim. A common arrangement was for compatriots in Australia or Hong Kong to sponsor their passage and the loan to be repaid through fraternal associations. Some returned to China but the majority put down roots or else moved on to new destinations, for these sojourners were as restless and enterprising as their European counterparts.

The effectiveness of this arrangement and the industry of the Chinese newcomers created resentment. ‘We want no slave class amongst us’, a Melbourne newspaper insisted in 1855. Bowing to popular pressure, the Victorian government imposed special entry taxes on Chinese immigrants and appointed protectors to segregate them on the goldfields, though this did not prevent a major race riot in 1857. The New South Wales government introduced similar restrictions after another attack on a Chinese encampment there in 1861. From this time onwards there was a racist strain in popular radicalism.

The Chinese accompanied the gold rush into north Queensland in the 1860s and the Northern Territory in the 1870s, and moved into horticulture, commerce and service industries. Gold in turn took European Australians into New Guinea, and the British government was startled to learn in 1883 that Queensland claimed its eastern half. London disallowed the action but annexed the southeast territory of Papua after Germany took the northeast segment. Earlier, in 1872, Queensland’s northern border had been extended into the Torres Strait to encompass islands that were rich in pearl, trochus, turtle-shell, trepang and sandalwood. The trade in these items extended both east and west, from Broome across to the outer Coral Sea, and proceeded along quite different lines from resource industries in the south. The work was performed by local or imported labour, using systems of employment developed on the beach communities of the Pacific.

Whereas pastoralism spread workers thinly over grasslands and agricultural selection spawned the family farm, the labour needs of the more intensive enterprises in the north called for different arrangements. Whether the white man was incapable of sustained physical effort in the tropics, as contemporary science suggested, or simply unwilling to become a plantation labourer, it was clear that some other source was needed. The sugar plantations that were established in north Queensland from the 1860s used the Pacific islands as a labour reserve. At first they drew on the New Hebrides (Vanuatu), whence the common term ‘kanakas’; later they turned to the Solomons and other island groups off the east coast of New Guinea for men and women to clear the forest, plant and weed the cane, then cut, crush and mill it into sugar. Sixty thousand of them were brought to Australia over forty years, some voluntarily and some at the point of a gun. Initially they worked as indentured labourers under close restriction for a fixed term and returned with European goods; by the 1880s a sizeable proportion settled with a substantial measure of freedom as part of the local working class.

Well-publicised cases of abuse brought growing criticism of the Pacific Island labour trade from humanitarians in the south. The ruthless behaviour of the ‘blackbirders’ who recruited the islanders, the harsh discipline of the planters, the high mortality rate and low rates of payment suggested a form of bond labour akin to slavery. A comparison might be drawn with penal transportation, which resumed in Western Australia between 1850 and 1868, for this too incurred the odium of eastern colonists. That the Western Australians had invited London to send convicts to remedy their labour shortage did not remove the stigma. But the west could be seen as a delinquent laggard on a recognised path of a development – it used convicts to construct public works and foster pastoralism and agriculture – whereas the plantation economy of the north suggested a more polarised and regressive social order. More than this, it threatened the growing concern for the racial integrity of Australia.

The Aborigines of the north played little part in the plantations but were substantially involved in maritime and other resource industries such as woodcutting. Through links with Torres Strait and Melanesian islanders, they were incorporated into the colonial economy far more extensively than further south. Their recruitment into the pastoral industry followed a process of invasion that was even more fiercely contested than that which had gone before and more shocking to the invader because it cost the lives of white women and children.

‘There is something almost sublime in the steady, silent flow of pastoral occupation over northern Queensland’, wrote the governor of that colony in 1860. ‘The wandering tribes of Aborigines retreat slowly before the march of the white man, as flocks of wild-fowl on the beach give way to the advancing waves.’ Yet a settler family of nine at Fraser’s Hornet Bank Station was massacred in 1857, and nineteen at Cullinlaringo (inland from Rockingham) in 1861. Soon the sheep were giving way to cattle, but still the fighting continued. At Battle Mountain, in far west Queensland, as many as 600 Aboriginal warriors confronted settlers and native mounted police in 1884. During the 1880s perhaps a thousand Aborigines were killed in the pastoral district of the Northern Territory.

So difficult was the European occupation of the north, and so demanding the circumstances of pastoralism there, that the occupiers had no alternative but to employ Aboriginal labour. The incorporation of Aboriginal communities into the open-range cattle industry gave participants a significant role. They constituted a pool of labour from which pastoralists drew drovers, servants and companions, who sustained them and maintained their enterprise. The lot of these Aboriginal workers has generated debate. Descendants of the pastoral pioneers recalled them as wayward children and later critics of racial inequality saw them as oppressed and exploited. More recently, as the northern cattle industry has declined, historians have drawn on the memories of Aboriginal informants to suggest how Aboriginal men and women ‘workin’ longa tucker’ managed both the land and the stockowners as well as the stock.

Further south, Aborigines were becoming wards of the state. Prior to self-government it was the Crown that stood between settlers and indigenous peoples; freed of that restraint, the colonial parliaments pushed them aside for agricultural settlement. The Victorian Board of Protection, established in 1859, regarded them as victims to be protected by confinement: ‘they are, indeed, but helpless children whose state was deplorable enough when this country was their own but is now worse’. Edward Curr, a pastoralist and sympathetic student of The Australian Race: Its Origins, Languages, Customs (in four volumes, 1886–7), told a subsequent inquiry that ‘The blacks should, when necessary, be coerced, just as we coerce children and lunatics who cannot take care of themselves’. At Coranderrk, in the upper Yarra Valley, 2000 hectares were provided in 1863 as a self-contained rural settlement under the direction of a white manager. Its residents ran stock, grew crops, operated a sawmill, a dairy and a bakery, but days were set aside for hunting and artefacts were produced for white purchasers in an early version of cultural tourism.

The urge to collect was premised on an anticipation of imminent disappearance. In Tasmania, the death in 1869 of an Aboriginal man who was taken (and believed himself) to be the last man of his people resulted in a macabre contest for possession of his skull between the local Royal Society and a doctor working for the Royal College of Surgeons in London. His widow, Truganini, was greatly disturbed by the mutilation and anxious that her body be protected from the men of science, but when she died seven years later, her remains were soon exhumed and the skeleton put on display at the Tasmanian museum in 1904. In novels, plays, films and postage stamps she appeared as the ‘last Tasmanian’, the representative of a sad but inevitable finality. Seventy years later Truganini’s skeleton was restored to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community; it was cremated and the ashes were scattered over the waterway her people had occupied. A British museum returned a shell necklace belonging to her in 1997, and the Royal College of Surgeons in London repatriated her hair and skin for burial in 2002.

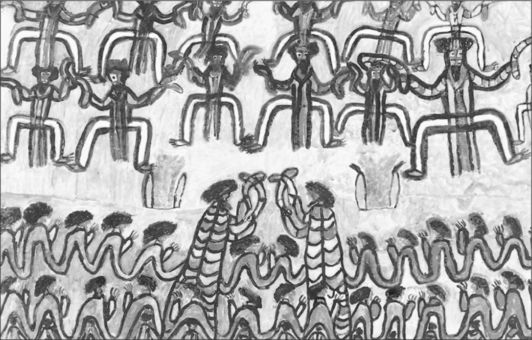

Among those who lived at Coranderrk was Barak, a man of the Wurundjeri clan of the Woi-worung people, who as a small boy had witnessed the signing of Batman’s ‘treaty’. Those associations were now regarded as quaint antiquities, for the custodial regime obliterated the territorial divisions of the Indigenous peoples and submerged their distinct identities, languages and social structures into the common category of Aborigines. Given the Christian name William and the title of the ‘last king of the Yarra Yarra tribe’, Barak produced drawings of aspects of traditional life: corroborees, with figures in possum-skin cloaks; hunting, with men pursuing emus, echidnas, snakes and lyrebirds; ritual fighting between warriors wielding boomerangs and parrying-shields. These closely patterned drawings embodied an ordered social structure integrated with the natural world.

William Barak (Wurundjeri c. 1824–1903) drew many versions of the corroboree. At the top of the drawing are two rows of dancers with boomerangs. Below them are two fires and in the lower section seated spectators keep the time by clapping, with two men standing over them in possum-skin cloaks. The design echoes the rhythmical pattern of the ceremony.

Corroborees were not permitted at Coranderrk; in 1887 the governor wished to see one but had to settle for a drawing by Barak. But this was not the only form of Aboriginal self-representation. In 1868 Thomas Wills, the inventor of Australian Rules football and a survivor of the Cullinlaringo massacre, took a team of Aboriginal cricketers from western Victoria to England. They alternated displays of their prowess with bat and ball with exhibitions of boomerang throwing and dancing. Whether by imitation of the white man’s ways or maintenance of their own, a powerful syncretism was resisting absorption and extinction.

***

Up to 1850 the increase in the European population of Australia matched the decline in the Aboriginal population. After 1850 the number of inhabitants rose rapidly, to over three million by 1888. A torrent of immigration during the first, heady years of the gold rush slowed to an irregular stream that again flowed rapidly in the 1880s. The rate of natural increase was also high: a woman who married in the 1850s was likely to bear seven children; one who married in the 1880s, five. Mortality declined with improved sanitation. Although one in ten babies died before the age of one and epidemics of infectious disease were still common, Australia was (with New Zealand and Sweden) the first country to reach a life expectancy of fifty years. Three million humans were more than the land had ever supported and required a more single-minded exploitation of its resources than had previously been attempted.

It was achieved by continuous improvement in the production of commodities for overseas markets. That improvement was in turn made possible by transfers of capital, labour and technology. The heavy investment by British financiers in the pastoral industry and the ready subscription of British savings to public loans raised by the colonies to finance railways and other utilities allowed for a rapid build-up of the capital stock. The decision of ambitious individuals and families to try their luck in Australia brought new skills and energies. The introduction of new methods and techniques to pastoralism, agriculture, mining and smelting stimulated a more general dynamic of adaptation and modification.

Sustained over three decades, the cumulative effect of these improvements brought remarkable material prosperity. Over thirty years an annual economic growth rate of 4.8 per cent was sustained. Australians earned more and spent more than the people of the United Kingdom, the United States, or any other country in the second half of the nineteenth century. The necessities of life were cheaper, opportunities greater, and differences of fortune less pronounced. Not all shared in the bounty. Low wages and irregular earnings pinched the lives of those without capital or work skills, but the capacity to set the working day at just eight hours indicated an economy operating well above subsistence level. First won by building workers in Melbourne in 1856, the eight-hour day was never general. It served rather as a touchstone of colonial achievement.

In the global economy created by European expansion, the imperial powers commanded the resources and exploited the populations of Africa, Asia and Latin America for their own benefit. In these colonies of sojourn, the European coloniser was concerned to extract raw materials for his factories; the colonised peoples were at the mercy of changes in technology and products, and the gap was widening. By contrast, settler colonies such as Australia were able to close the gap, to increase local capacity and enjoy its benefits.

The efficiency gains of rural industries left the majority of the workforce free to pursue other activities. Some processed food and made household goods, some were employed in construction, and some in the widening range of service industries. An increasing number went into workshops that produced a growing range of items formerly imported from Britain. The growth of towns was a distinctive feature of these prodigious settler colonies. Even during the gold rush and the wave of agricultural settlement that followed, two out of every five colonists lived in towns of 2500 or more inhabitants. By the 1880s towns held half the population, a far higher proportion than in Britain, higher also than in the United States or Canada. Even smaller towns supported a range of urban amenities: hotel, bank, church, newspaper, flourmill, blacksmith and stores. No less than international trade, the Australian town created an economy of market-minded specialist producers.

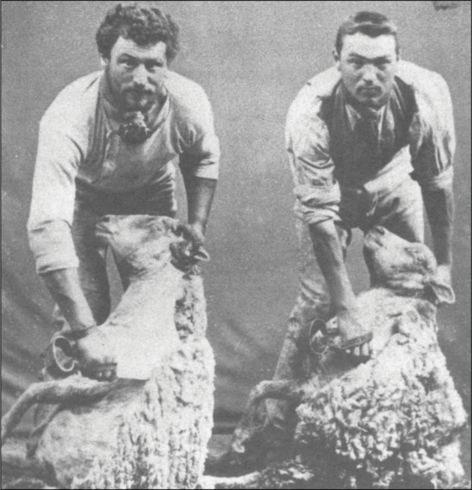

Shearers at work on a station near Adelaide. These men use blade shears, which were replaced by machine shearing at the end of the century. Some 50,000 men were employed during the shearing season.

In every colony the capital city consolidated its dominance. It was the gateway, the rail terminus and the principal port, the place where the newcomer disembarked and, after the gold rush, usually stayed. It was the commercial, financial and administrative hub, and used its political leverage to augment control over the hinterland. Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Hobart, Adelaide and Perth, each one of them coastal cities established before the settlement of their inland districts, were separated from each other by at least 800 kilometres and movement between them was by sea. Perth, the most isolated, was still hardly more than a township with 9000 inhabitants in 1888; Hobart languished with 34,000. Brisbane and Adelaide had grown into large regional towns of 86,000 and 115,000 respectively. Melbourne, with 420,000, and Sydney, with 360,000, were the behemoths. Of the North American cities, only New York, Chicago and Philadelphia exceeded Melbourne. Work began in 1888 on a building in its business centre that rose 46 metres, and Melbournians liked to claim it was the highest in the world; a more likely ranking is that it was the third-highest.

Each of the colonial capitals presented the visitor with its own appearance and atmosphere: torpid Perth on the sunlit estuary of the Swan River; trim Hobart beneath a brooding mountain; vigorous Brisbane with airy bungalows in lush sub-tropical splendour; the orderly cottages of Adelaide framed by spacious parklands; Sydney’s crooked sandstone terraces on the slopes around its majestic harbour; the ornate iron lacework on the rows of houses set out on the flat grid of Melbourne. Pressed for an admiring response to these various places, the visitor was more likely to register their common features. Each metropolis sprawled over a large area with low population densities. Each was surrounded by extensive suburbs, linked to the centre by public transport and served by other utilities, though all but Adelaide lacked sewerage and the primitive sanitation was noisome during the long summers.

The houses were more spacious than those of older cities (four rooms or more was now the norm) and there was already a preference for the single-story cottage or bungalow on a substantial allotment. Half or more were owned by their occupants. This generous residential provision absorbed a high proportion of private capital and cost the occupiers a considerable part of their incomes, but food was cheap and families took pleasure in their own house and garden. The small scale of most enterprises, the infrequency of large factories and the absence of the crowded tenements typical of the great nineteenth-century cities with their teeming masses of peasants-turned-proletarians, all testified to the modest comfort of the Australian commercial city.

Such reflections would scarcely satisfy the colonial need for affirmation. The colonists of the New World, as they increasingly thought of themselves, wished both to emulate and surpass the models of the old. The cities were their showplaces, and they expected the increasing numbers of celebrities, travel writers and commentators who came out to Australia to praise their achievement. ‘Marvellous Melbourne’, a title conferred by a visiting British journalist, embarked during the 1880s on a heady boom. Its pastoralists had expanded across the Murray River into the southern region of New South Wales and spearheaded the Queensland sugar and cattle industries. Its manufacturers took advantage of protective tariffs to achieve economies of scale in the largest local market and sell to other colonies. Its merchants created plantations in Fiji and demolished kauri forests in New Zealand. Its financiers seized control of the rich Broken Hill mine, its stock exchange buzzed with flotations on other minefields. The ready availability of foreign investment inflated a speculative bubble of land companies and building societies.

There was a strong Scottish presence among Melbourne’s business class and, in the words of an emigrant Scot, ‘There are few more impressive sights in the world than a Scotsman on the make.’ Single-minded in the pursuit of wealth, these calculating men marked their success with flamboyant city offices and suburban palaces. Morally earnest, they worshipped in solid bluestone churches and raised stately temperance hotels. Confident and assertive, they assumed their capacity to guide social progress and took pleasure in sport and display. An unsympathetic observer suggested that,

In another hundred years the average Australian will be a tall, coarse, strong-jawed, greedy, pushing talented man … His religion will be a form of Presbyterianism, his national policy a Democracy tempered by the rate of exchange. His wife will be a thin, narrow woman, very fond of dress and idleness, caring little for her children, but without sufficient brain power to sin with zest.

That observer was Marcus Clarke, a literary bohemian who complemented the boastful achievements of Marvellous Melbourne with the exotic images of low life in Outcast Melbourne. The squalor and crime of the inner-city slums, the gambling dens of Chinatown, the dosshouses and brothels of the lanes and alleyways, all just a short distance from the clubs and fashionable theatres, provided bohemians and moral reformers alike with a repertoire of city life as compelling in cosmopolitan ambience as the stock exchange or the sporting oval. Fergus Hume’s crime novel, The Mystery of a Hansom Cab (1886), became an international bestseller with its interplay of the bright daytime respectability of Marvellous Melbourne and the shadowy nightlife of Outcast Melbourne, both in their own ways places where people cast off their pasts to assume new identities: ‘Over all the great city hung a cloud of smoke like a pall.’

The man of the house at ease with a magazine while the woman reads the Christmas mail. The lush fernery frames the verandah of their urban villa and the light clothing emphasised the summer warmth of the antipodean setting.

The same process of reinvention was apparent in those more intimate literary products of a settler society: the diary and the letter. Mail was the chief link between separated kith and kin. It cost sixpence to send a letter home, and took months for it to reach its destination, but 100,000 were sent back monthly during the 1860s and as many arrived from Britain and Ireland. At both ends of the oceans, a circle of family, friends and neighbours formed at the arrival of the mail to share the news from the other side of the world.

Uncollected letters at the colonial post offices bore mute testimony to the fragility of these threads. Death, disgrace or despair might terminate communication with relatives back home; alternatively, a long silence might be broken decades later by a dispatch from the backblocks or even a dramatic reunion. Newcomers moved freely in colonial society and quickly formed new associations, so that half of all Irish brides who married in Victoria in the 1870s took a non-Irish husband. It was the same with patterns of residence. The 1871 census revealed just one electoral district in which Catholics (and that religion was almost synonymous with Irish descent) made up more than half the population. In Australia the English, Scots, Welsh and Irish lived alongside each other.

The effects were apparent in patterns of speech. First-comers spoke in British regional dialects, but their children shared a distinctive nasal twang and flat pronunciation. School inspectors noted how these young Australians elided syllables, dropped aitches, turned –ing endings into –en, and were incorrigible users of diphthongs: hence a cow was a ‘caow’, take became ‘tike’, and you would ‘hoide’ rather than hide. The lack of social or geographical differentiation spoke eloquently of a fluid, mobile society.

Many from the old country mistook these speech patterns for those of working-class Londoners. The novelist Charles Dickens, who had a keen ear for Cockney, did not. He used Australia as a device to dispatch a redundant character, including two of his own sons. For Arthur Conan Doyle, at the century’s close, it offered a ready supply of enigmatic returnees suitable either as victim or culprit, whom Sherlock Holmes invariably detected through their recourse to the shrill cry of ‘cooee’ (a piercing call supposedly adopted from the Dharug people east of Sydney) or some other colonial hallmark. The lost inheritance of the antipodean exile and the windfall legacy from a long-forgotten colonial relative became a stock-in-trade of fictional romance.

Within Australia, the restless motion of arrival and departure presented particular problems for those in dependent relationships: special laws and special arrangements were needed for deserted mothers and children. Colonists responded to these uncertainties by reproducing the familiar forms of civil society. Here they displayed a marked preference for voluntarism, not so much a check on government as a supplementation of it. For all their reliance on state support in the pursuit of economic development and material comfort, they built their economy and satisfied their needs through the market. The market rewarded those who helped themselves and encouraged exchanges based on self-interest; when extended to other areas of social life in a settler society committed to advanced democracy, the impulse for gratification opened an enlarged space for personal choice.

The freedom of the individual, however, was premised on the expectation that it would be exercised responsibly. If the law of supply and demand threatened social cohesion, it was abrogated: hence the appeal of the eight-hour day as a protection of labour against excessive toil. That expressive national phrase ‘fair dinkum’ derives from the English midlands, where ‘dinkum’ means an appropriate measure of work. ‘Fair dinkum’ and ‘fair go’ took on wider meaning in Australia to mark out a normative code that applied more widely to other aspects of social interaction.

The social norms were expressed most fully in voluntary dealings where individuals approached each other as equals united in common purpose. Voluntarism combined the expectation of individual autonomy with the need for mutuality that was all the more urgent in a land of strangers. Clubs and societies provided for their interests and recreations, sporting associations for their games, lodges for companionship, learned societies for the advancement of knowledge and literary societies for its display, mechanics’ institutes for self-improvement, friendly societies and mutual benefit organisations for emergencies.

The family, the most intimate form of association, was bound tightly. Both the reduction in the numerical imbalance of men and women, and the continuing legal and economic imbalance between the sexes, made for high rates of family formation. Holy wedlock was now the norm, reinforced by laws that controlled a wife’s property and offspring, and provided few opportunities for her to escape an oppressive husband. The couple’s fortunes usually depended upon his capacity as a provider and hers as a domestic manager. Yet even within this unequal partnership the voluntary principle still operated. Both bride and groom chose each other freely and quickly established autonomy from parents and in-laws in their own household. In the colonial family, furthermore, the wife typically played a more active role and was more closely involved in crucial decisions. Children, similarly, carried greater responsibilities and enjoyed greater licence.

Even in worship the same tendencies were apparent. It was already established that there was no official religion in Australia, and that all were entitled to worship as they chose. This was in part a recognition of ethnic diversity: the overwhelming majority of Catholics were Irish, most Presbyterians Scottish, and they demanded equality of status with the Church of England. The colonies had formerly encouraged the activities of the principal Christian denominations with financial support, but even this form of religious assistance was now withdrawn under challenge from the voluntarists.

Yet this was a period of religious growth. Both church membership and church attendance increased markedly from the 1860s. The visiting English novelist, Anthony Trollope, was struck by the popularity of worship in Australia and thought it indicative of the prosperity of the colonists and a corresponding desire for respectability: ‘decent garments are highly conducive to church-going’, he wrote. A similar impetus was apparent in church building, as the principal denominations raised large places of worship in stone or brick, with spires and ornamentation. A religion of sentiment flourished, as hymn singing spread and sermons became more intense. This fervour in turn stimulated a range of Christian missions and charities, while it promoted an ethic of self-discipline, industry, frugality and sobriety.

Australia became a fertile field for the new methods of revivalism pioneered by Moody and Sankey, and overseas evangelicals toured the colonies to preach before mass gatherings. The major denominations had little need of these influxes of international expertise since they maintained close links with their parent churches. Anglicans continued to recruit their bishops from England and address them as ‘my lord’; they built big in the Gothic style, introduced choirs, surplices, organs and church decoration. Now led by Irish bishops, Catholics responded enthusiastically to Pope Pius IX’s proclamation of papal infallibility, and their work was assisted by the introduction of a number of male and female orders from France and Spain as well as Ireland. Catholicism in Australia was a religion that stressed discipline and obedience under clerical guidance. As the faith of a minority group with little fondness for British rule, it was also a strong force for Australian nationalism.

The evangelical religion of the dissenters became the majority faith of active Christians during the second half of the nineteenth century. Their more localised, less hierarchical forms of government, and the greater involvement of their laity made for higher rates of worship. In Victoria and South Australia, where Presbyterians, Methodists, Congregationalists and Baptists were strongest, they exerted a powerful influence on society at large: pubs and shops closed on Sunday, few trains ran and public amusements were prohibited. Yet even this stern puritan discipline was under challenge. As early as 1847 the poet Charles Harpur detected an ‘individualising process’ at work in colonial religious life that could not be stopped. The growing challenge of science and reason weakened the hold of dogma. Some clung to their religion, some cast it off, and others felt the loss of faith as a painful but inescapable necessity. The crucial point was that all these alternatives were available. By 1883 even the devout George Higinbotham could see no alternative but to ‘set out alone and unaided on the perilous path of inquiry’.

Up to the middle of the century the churches had been the chief providers of education; henceforth the state assumed that role. It entered the field primarily because of the failure of church schools – in 1861 only half the children of school age could read and write – but the withdrawal of state aid was hastened by rancorous denominational particularism. The creation of an alternative system of elementary education – secular, compulsory and free – was prompted by a desire to create a literate, numerate, orderly and industrious citizenry. ‘The growing needs and dangers of society’, declared Higinbotham in 1872, demanded ‘a single centre and source of responsible authority in the matter of primary education’; it must of necessity be the responsibility of the state. The provision of state schools in every suburb and bush settlement made a heavy call on public outlays; the teachers and administrators comprised a substantial part of the public service. Centralised, hierarchical and rule-bound, the education departments were prototypes of the bureaucracy for which Australians demonstrated a particular talent.

The universities that were established in Sydney (1850), Melbourne (1853) and Adelaide (1874), similarly, were civic institutions, established by acts of parliament, supported by public appropriations and controlled by lay councils. Melbourne even prohibited the teaching of theology. Their founders hoped that a liberal education in a cloistered setting would smooth rough colonial edges and elevate public life. In practice the universities quickly developed a more utilitarian emphasis on professional training. Preparation of lawyers, doctors and engineers became the chief justification of a restricted and costly higher education.

For that matter, the expectation that the ‘common’, ‘public’ or ‘state’ school (the various cognomens conveyed a wealth of meaning) would redeem the rising generation of colonial children, enhance their capacity and nurture a common purpose proved illusory. Some teachers brought the centrally prescribed curriculum to life. Some pupils caught from it a spark that fired their imaginations. For the most part, however, the government school operated as a custodial institution. The ringing of the bell and marking of the roll instilled habits of regularity. Ill-trained and hard-pressed teachers drilled their charges in the rudiments of reading and writing, instructed them with moral homilies and released them into the workforce in their early teens.

Nor was the goal of a common education – secular, compulsory and free – ever achieved. Catholics shunned what the Archbishop of Sydney described as ‘an infidel system of education’, and made extraordinary sacrifices to construct their own system. Mother Mary MacKillop – who in 1866 helped found the Order of Josephites, dedicated to the education of the Catholic poor, especially in the outback – became an inspiration for this mission. Her refusal to submit to authority brought temporary excommunication and an episcopal antagonism that persisted throughout her life, but she has since been elevated into a national hero. In 1995 Pope John Paul II visited Sydney to celebrate her beatification, and in 2010 Mary McKillop became Australia’s first and only saint. The Protestant schools operated at the other end of the social ladder by filling the gap between elementary and higher education for the well-to-do.

The state persisted, nevertheless, in its promotion of a common culture. Museums, galleries, libraries, parks, botanical and zoological gardens were among the sites of rational recreation and self-improvement. While imitative of established models (Melbourne’s public library began with a blanket order for all the works cited in Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, its gallery with plaster casts of classical friezes and statuary), the civic emphasis gave such institutions a distinctive character, at once high-minded, didactic and popular. Their public function in turn shaped cultural forms. The privately commissioned portraits and domestic paintings of earlier colonial artists gave way to the romantic landscapes of Conrad Martens and Eugène von Guérard and the monumental history canvases of William Strutt. The proliferation of commercial theatre, sport and other recreational activities testified to the extent of discretionary expenditure as well as the time and space to enjoy it. From 1877 England and Australia began playing regular cricket matches. The first Australian victory on English soil in 1882 gave birth to a mock obituary to England’s supremacy and thus the Ashes, which are the world’s oldest international sporting contest.

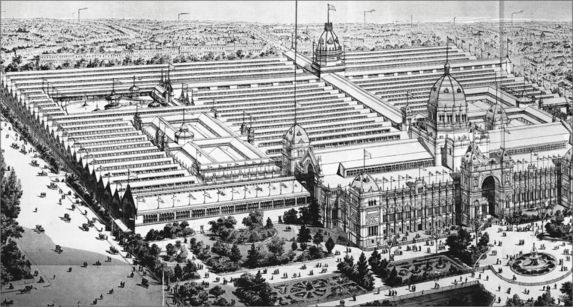

The Melbourne international exhibition of 1880–81 was the grandest of all the colonial exhibitions, with two million visitors. The temporary pavilions were subsequently removed, leaving the principle domed building as a lasting monument to ‘Marvellous Melbourne’.

An English visitor to Melbourne in the late 1850s was struck during her morning perambulations by the sight of a newspaper on every doorstep. By 1888 there were six hundred of them with circulations that ranged from a few hundred to 80,000. The newspaper extended the process of voluntary association far beyond the limits of the public assembly and the spoken word. It exploited technological improvements – the overseas telegraph, the mechanised press, cheap pulp-based paper and rapid, regular transport – to reach a mass audience. It was itself a commodity and enabled buyers and sellers to operate in a market that was no longer confined to a place. It both reported events and interpreted them, mobilised the public as a political force and constituted the reader as a sovereign individual.

The power of the press was unmistakable: more than one Victorian premier submitted the names of his ministers for the approval of David Syme, the majority owner of the Melbourne Age. Some thought of journalism as constituting a fourth estate of government; though since the colonies lacked lords spiritual and temporal, their newspapers might claim a higher precedence. Even this was not enough for Syme: a lapsed Calvinist and trainee for the ministry, he exercised stern moral vigilance over every aspect of colonial life. ‘What a pulpit the editor mounts daily’, the Age boasted, ‘with a congregation of fifty thousand within reach of his voice.’ A forthright secularist, land reformer and advocate of protection, he was the most advanced in his liberalism, but other newspaper owners with similar Nonconformist connections lent their support to schemes of material and moral progress as befitted a property-owning democracy. John Fairfax, the owner of the Sydney Morning Herald, was a Congregational deacon, and John West, its most notable editor, had been a minister in the same church. So too was the founder of the Adelaide Advertiser.

The colonies marked their progress in bricks and mortar, but also in amenities, achievements and anniversaries. In 1888 Sydney marked the centenary of the arrival of the First Fleet with a week of celebrations. There was a civic procession and a banquet with portraits of Wentworth and Macarthur looking down on the table of dignitaries. A statue of Queen Victoria was unveiled in the city and a new Centennial Park opened in swampy land to the south. Parcels of bread, cheese, meat, vegetables and tobacco were distributed to the poor, though not to the Aborigines. ‘And remind them we have robbed them?’ was Henry Parkes’ sardonic retort to this suggestion. Parkes himself wanted to raise a pantheon in the new park to house the remains of the nation’s honoured dead and the relics of both European and Aboriginal Australia, but his idea met a fate similar to William Wentworth’s earlier call for a colonial peerage. ‘We have not advanced to that stage of our national life when we have any great heroes to offer’, observed a radical critic.

Parkes also proposed that New South Wales be renamed Australia, but this too was mocked into oblivion: one Victorian suggested ‘Convictoria’ would be more apt. Victoria responded later in the year with a Centennial Exhibition, the most ambitious and expensive of these exercises in colonial promotion modelled on London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. Two million visitors entered the pavilions where every imaginable kind of produce was on display, along with decorative and applied arts. There was also a cantata that dramatised the colonial progress from rude barbarity to urban splendour:

Such affirmative comparisons of then and now were a stock-in-trade of colonial writing. That a note of uncertainty should be struck in the centennial year and at the very height of colonial vainglory suggests a remarkable foresight.