The Jondaryan station occupied 60,000 hectares of grazing country in the Darling Downs district of south Queensland in the 1880s, and employed seventy hands. Twice a year, in late spring and early autumn, some fifty contract workers would assemble there and cut away the fleece of more than 100,000 sheep. They lived in primitive quarters close to the shearing-shed, where six days a week from sunup to sundown they bent down over the ewes and plied their shears. Charges for rations and fines for improperly shorn sheep or other infractions were deducted from their earnings. In the late 1880s the Queensland shearers formed a union to secure better pay and conditions, and by December 1889 it had enrolled 3000 members. The union demanded that pastoralists employ union members only; the Darling Downs employers refused.

The shearers gathered at Jondaryan in September 1889 and set up camp till the manager acceded to their demands. The manager sought non-union labour to break the strike: as one shearer put it, the station ‘got a lot of riffraff from Brisbane who “tommy-hawked” the wool off somehow’. But when the wool bales were railed to Brisbane for shipment to England, the waterside workers refused to handle them and declared the wool would ‘stay there till the day of judgement and a day or two after’ if the owners of Jondaryan did not concede the union conditions. The station manager met with other members of the Darling Downs Pastoralists Association in May 1890, which sent representatives to a conference in Brisbane of pastoralists and shippers who agreed they would employ only union shearers. Only then were the 190 bales of Jondaryan wool released for shipment.

The victory of the Queensland Shearers Union encouraged the Australian Shearers Union, which covered the southern colonies. It too was challenging the tyranny of the wool kings and pressing for exclusion of non-union labour from the woolsheds. But the pastoralists and shipowners were determined to resist the union demands, and responded to the alliance of rural and urban workers with their own union of employers. ‘The common saying now is the fight must come’, announced the president of the Sydney Chamber of Commerce in July 1890, ‘and most employers add the sooner the better’. The fight came in the following month when the shipowners told the recently formed Marine Officers Association that, before its wage claims could be discussed, the association’s Victorian members must end their affiliation with the Melbourne Trades Hall Council. The marine officers walked off their ships, the waterside workers refused to load them, the coalminers refused to supply coal to the bunkers, the colliery owners locked them out and the pastoralists broke off negotiation with the shearers.

The Maritime Strike, as it became known, spread further. The owners of the Broken Hill silver and lead mine locked out their workers; the Labour Defence Committee brought out the transport workers who linked the wharf and the railhead to the factory and the shop; the gas stokers, who provided the city with its power and illumination, refused to work with coal cut by strikebreakers. A city without light! What forces of disorder might that release? ‘The question’ for Alfred Deakin, the chief secretary of Victoria, ‘was whether the city was to be handed over to mob law and the tender mercy of roughs and rascals, or whether it was to be governed, as it had always been governed, under the law in peace and order’. He called out the part-time soldiers of the local defence force, who confronted union pickets at the port of Melbourne and were instructed by their commander that if necessary they should ‘fire low and lay them out’. In Sydney the government of Henry Parkes sent special police with firearms to Circular Quay to clear a passage for wool-drays through a menacing crowd. In Queensland, where the pastoralists seized the opportunity in early 1891 to renege on their earlier agreement with the shearers, Samuel Griffith as premier also called out the defence force and read the Riot Act.

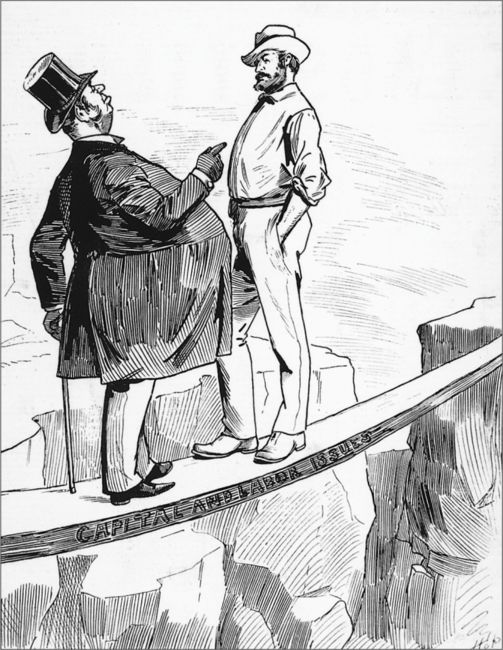

In this contemporary depiction of the Maritime Strike, Capital and Labour confront each other across a precipitous divide. Capital appears as an overbearing Mr Fat, Labour as a lean and resolute working man.

The employers, the police, the troops and the courts broke the great Maritime Strike before the end of 1890. In 1891 and again in 1894 the pastoralists once more defeated the shearers; the mine-owners of Broken Hill repeated their victory in 1892 and the coal-owners theirs in 1896. Other, less organised workgroups simply crumbled before their employers’ demands: perhaps one in five wage-earners belonged to a union in 1890 but by 1896 scarcely one in twenty did. The confrontation between the workers, with their demand for a ‘closed shop’, and the employers, who insisted on ‘freedom of contract’, had ended with a decisive victory for the latter. The colonial governments’ interpretation of ‘law and order’ ensured that all attempts to prevent the introduction of non-union strikebreakers failed.

Yet the events of the early 1890s had a lasting effect. The unrest in the cities frightened liberal politicians such as Deakin and Griffith into alarmed repression. The conflict in the countryside resulted in a far more draconian punishment. The Southern Cross flag flew over the camps of striking shearers, who in revenge for their victimisation burned grass, fences, buildings and even riverboats. The bush was put under armed occupation, the ringleaders rounded up and imprisoned for sedition and other crimes. An era of liberal consensus that reconciled sectional interests in material and moral progress had passed.

One reason for the alarm was the suddenness of this polarisation of employer and employee. Local associations of masters and craftsmen in particular trades had dealt with each other for decades within a shared framework of mutual obligations and shared values. Then, in the late 1880s, new unions sprang up to enrol all workers in their industries, and proclaim solidarity with other workers, not just here but around the world – in 1889 the Australian unions subscribed £36,000 to the strike fund of the London dockers. Employers formed their own combinations and they too abandoned the language of moral suasion for the rhetoric of confrontation. An illusion of harmony gave way to open antagonism as the two sides faced each other across the barricades of class warfare.

The liberals were not alone in their disillusionment. For Henry Lawson, a boy from the bush who had recently joined his mother in Sydney and was caught up in the radical fervour, the attack on workers was shocking and the response defiant:

His mother, Louisa Lawson, had fled an unhappy marriage and published Henry’s first verse in her magazine, the Republican – its mission, ‘to observe, to reflect, and then to speak and, if needs be, to castigate’. For mother and son, the need was urgent.

For William Lane, an English migrant who edited the newspaper of the Queensland labour movement, the defeat was final. He had come to Australia as a place of redemption from ‘the Past, with its crashing empires, its falling thrones, its dotard races’. Now the serpent of capitalism had invaded the Edenic new world, and the racial and sexual integrity of The Workingman’s Paradise (as he entitled his novel of the strike) was defiled. In 1893 Lane set sail with more than two hundred followers to start anew in Paraguay, where his messianic puritanism soon brought discord in the socialist utopian settlement he called New Australia. One of Lane’s followers was a young schoolteacher, Mary Cameron, linked romantically to Henry Lawson before she sailed across the Pacific:

She returned in 1902 as Mary Gilmore and accompanied her husband to his family’s rural property. Writing sustained her from this ‘descent into hell’, and in 1908 she became the contributor of a woman’s page for the principal union paper, the Australian Worker. As poet, commentator and correspondent, Mary Gilmore fashioned herself into a national bard.

For W. G. Spence, the founder of the Australian Shearers Union, the actions of 1890 revealed a different lesson. As he set them down in his memoirs, they brought about Australia’s Awakening. First there was stirring of Australian manhood into the fraternity of unionism, which elevated mateship into a religion ‘bringing salvation from years of tyranny’. Then came the industrial war, ‘which saw the Governments siding with the capitalists’, and revealed the true nature of both. This revelation in turn ‘brought home to the worker the fact that he had a weapon in his hand’ that could defeat them and bring final emancipation: the vote. Within a year of their defeat in the Maritime Strike, the trade unions of New South Wales formed a Labor Electoral League that won thirty-five of the 141 seats in the Legislative Assembly. Similar organisations emerged in the other colonies and came together at the end of the decade as the Australian Labor Party. By 1914 the Labor Party had experience of government nationally and in every state. Spence himself wrote Australia’s Awakening from the federal parliament.

The bush poet, Henry Lawson, is shown humping his swag with waterbag and billy. Although Lawson had gone briefly up-country in the summer of 1892–93, he lived most of his adult life in Sydney.

It was a dramatic reversal of fortune. Long before the British Labour Party achieved more than token representation, even while the socialist parties of France and Germany were still contending for full legitimacy, the stripling Australian Labor Party won a national electoral majority. Union membership recovered to one-third of all wage-earners by 1914, a level unprecedented in any other country. That precocious success stunted the Australian labour movement. The achievement of office while still in its infancy turned the Labor Party into a pragmatic electoral organisation. Its socialist founders either moderated their principles or were pushed aside. Its inner-party rules, designed to ensure democratic control, were used to consolidate the dominance of the politicians. As early as 1893 the Queensland shearer Thomas Ryan, who had been charged with conspiracy in 1891 and elected to parliament in 1892, proclaimed the results: ‘The friends are too warm, the whiskey too strong, and the seats too soft for Tommy Ryan. His place is out among the shearers on the billabongs.’

Ryan had been chosen as the Labor candidate by workers gathered under a spreading ghost gum tree that stood at the entrance to the railway terminus at Barcaldine in central Queensland, where just a year earlier striking shearers and shed-hands congregated to read the jeremiads of William Lane. It was known as the Tree of Knowledge and its forbidden fruit was parliamentarism. The tree stood for more than a century, a hallowed symbol of Labor mythology, until in 2006 it was poisoned. But when Ryan returned to his workmates, there was no lack of volunteers to take up the burden of parliamentary duties.

The creation of a political party out of the wreckage of a crushing industrial defeat presaged a new force that would soon impel the earlier political groupings, liberal and conservative, to form a single anti-Labor Party. Henceforth politics was organised on class lines and the mobilisation of class loyalties affected every aspect of public life. The differences so clearly expressed in the events of the Maritime Strike produced a solidarity that was almost tribal in its intensity, the workers determined that they should prevail, the capitalists adamant that they should not. Alfred Deakin predicted accurately in 1891 that ‘the rise of the labour party in politics is more significant and more cosmic than the Crusades’.

The wave of strikes and lockouts occurred as the years of prosperity and growth ran out. Wool prices had been slipping since the 1870s (the drive of the pastoralists for greater productivity underlay the conflict in that industry). There was an increased reliance on British investment both for government expenditure on public works and for private urban construction. Both were marked by excessive optimism, cronyism and dubious business practice, for the same promoters were active in the cabinet and the boardrooms, and easy credit fuelled the land boom that reached its peak in Melbourne.

By 1890 the cost of servicing the foreign debt absorbed 40 per cent of export earnings. The London money market took fright in that year when several South American governments defaulted, and refused new loans to Australia. Then some of the riskier land companies failed and the drain on bank deposits quickened into a run. In the autumn of 1893 most of the country’s banks suspended business, plunging commerce and industry into chaos. To add insult to injury, many of Melbourne’s land boomers used new laws to escape their creditors. A deep suspicion of the ‘money power’ was a lasting legacy of the depression of the 1890s.

Between 1891 and 1895 the economy shrank by 30 per cent. As employers laid off hands, the number of unemployed reached a third of the workforce and this at a time when there was no public provision of income support. Charities provided assistance to women and children, and work schemes were created for men, but these were pitifully inadequate to cope with the need. Some fled to Western Australia, where the discovery of new gold deposits brought fresh British investment and attracted 100,000 easterners. Some tramped the bush in search of work or handouts. Those who went ‘on the wallaby’, the expressive phrase Henry Lawson had used, rolled their possessions in a blanket to form a swag. In these hard times a distinction was drawn between the swagman who was prepared to work for a feed and the sundowner who arrived at the end of the day seeking a free supper.

A sharp decline in rates of marriage and childbirth indicated the extent of poverty and insecurity. Immigration came to a halt after 1891: there was a net inflow of just 7000 during the rest of the decade. Australian incomes did not regain their pre-depression level until well into the following decade. An entrenched caution and aversion to dependence were additional long-term effects of the depression.

After depression came drought. From 1895 to 1903 a run of dry years parched the most heavily populated eastern half of the continent. The land was already under pressure as the result of heavy grazing and repeated cropping. After supporting human life for tens of thousands of years the country had been conquered and remade in less than a century. The sudden change of land use from subsistence to gain and the introduction of new species and practices determined by an international flow of credit, supplies and markets brought drastic environmental simplification, imbalance and exhaustion.

The signs were already apparent in habitat destruction by exotic plants and animals. By the 1880s rabbits, which had ruined pastoral properties in Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales, spread north into Queensland, and in the 1890s they crossed the Nullarbor Plain into Western Australia. When drought killed off the last of the ground cover, the land was bare. Dust storms swallowed up dams and buried fences. The largest of them in late 1902 blotted out the sky, covering the eastern states with a red cloud that even crossed the Tasman to descend on New Zealand, 3000 kilometres to the east. Between 1891 and 1902 sheep numbers were halved.

***

Discord, depression, drought. The horsemen of the apocalypse rode over the continent and trampled the illusions of colonial progress. Yet from these disasters arose a national legend that maintained a powerful hold on succeeding generations. It was created by a new generation of writers and artists who adapted received techniques into consciously local idioms. In their search for what was distinctively Australian they turned inwards, away from the city with its derivative forms to an idealised countryside. This countryside was no longer a tranquil Arcadian retreat. In the paintings of Tom Roberts and Fred McCubbin it was a landscape of dazzling light. In the ballads and stories of Henry Lawson it was harsh and elemental.

The green tones of the pastoral romance gave way to the brown of the bush, the squatter and his homestead to the shearer, the boundary rider, and other itinerant bush workers whom a visiting Englishman described in 1893 as ‘the one powerful and unique national type produced in Australia’. With the nomad bushman were associated fierce independence, fortitude, irreverence for authority, egalitarianism and mateship – qualities that were no sooner suppressed in the war against the bush unions than they were claimed for the nation at large.

The weekly Bulletin magazine was the chief medium of this national self-image. Founded in 1880, it practised an exuberant and irreverent mockery of bloated capitalists, monocled aristocrats and puritan killjoys, while it championed republicanism, secularism, democracy and masculine licence. From 1886, when the Bulletin threw its pages open to readers, thousands of the beneficiaries of mass education were drawn into an enlarged republic of letters. Here Lawson and A. B. Paterson jousted in verse, the one a refugee from the horrors of the outback, the other a pastoralist’s son turned city lawyer who extolled its majestic plenitude – though Paterson also wrote ‘Waltzing Matilda’, the song of the tragic swagman who probably plunged into the billabong to evade the troopers because he was an organiser of the striking shearers. Here too appeared Steele Rudd, with his bucolic jocularity at the expense of the hapless Dad and Dave on their selection; Barbara Baynton, a selector’s wife, who wrote of the malevolence of the bush and the brutality of its men; and John Shaw Neilson, who span songs of spare beauty out of his grim lot as a failed selector’s son.

The outback is never kind to women and children. Lawson’s laconic irony sustains the idealism and sentimentality of masculine bonding, but his most powerful stories tell of women with absent husbands who are left to fight the terrors of the bush. Nature in Australia has a dark side that defies ordinary logic and eventually drives its human victims mad. Just nineteen years old, Miles Franklin related My Brilliant Career (1901) as a rebel against her fate as the daughter of a dairy farmer: ‘There is no plot in this story’, she explained, ‘because there has been none in my life’. Joseph Furphy, failed selector, bullock-driver and finally a wage-worker in his brother’s foundry, opened Such Is Life (1903), the most complexly nomadic of the novels of the period, with the sardonic exultation ‘Unemployed at last!’ He sent the manuscript to the editor of the Bulletin in 1897 with the characterisation: ‘temper democratic: bias, offensively Australian’. Yet even Lawson, the most gifted of the radical nationalist writers, soon retreated into the platitudes of ‘The Shearers’ (1901):

The bush legend was just that, a myth that enshrined lost possibilities, but one that could be tapped repeatedly for new meaning. Even in the 1980s it allowed an unsophisticated crocodile hunter to triumph over hard-boiled New Yorkers in a Hollywood feature film.

Crocodile Dundee was the creation of a street-wise former maintenance worker on the Sydney Harbour Bridge. The bush legend of the 1890s was shaped by men who clung to the city despite their dissatisfactions with its philistine respectability. Lawson had grown up in the bush but his knowledge of the outback derived from a brief foray in the summer of 1892–93 into southwest Queensland. ‘You have no idea of the horrors of the country here’, he wrote to his aunt; ‘men tramp and beg and live like dogs’. The plein air artists of the Heidelberg school ventured just a few kilometres beyond the suburbs of Melbourne to set up camp and paint the scrub. Tom Roberts executed the iconic pastoral work, ‘Shearing the Rams’, in his city studio after a short trip up-country. Charles Conder used Sydney Harbour and its adjacent waterways for his impressionist paintings. The Bulletin was known as ‘the bushmen’s bible’, but it was created and produced in Sydney by alienated intellectuals who projected their desires onto an imagined rural interior and allowed city readers to partake vicariously in the dream of an untrammelled masculine solidarity.

All settler societies have their frontier legends. Whether it be the sturdy independence found in the American West by Frederick Jackson Turner, or the escape from bondage that Boers commemorated in their Great Trek, white men attach themselves to the land in a nationally formative relationship. In challenging such myths, revisionist historians do not dispel the aura of national origins so much as rework them to discover alternative foundations. Thus the Australian feminist historians who contested the misogyny of the legend of the nineties still saw the nomad bushman as emblematic, only they interpreted his freedom as a repudiation of domestic responsibilities. The masculinity the Bulletin celebrated was a licence to roam. Its writers and cartoonists mocked those who would hobble the lone hand: the nagging housewife, the prim parson and the assembled forces of wowserdom (wowser was an expressive local term for those who sought to stamp out alcohol, tobacco and other pleasures). The principal contest at the turn of the century, these feminist critics suggest, was not the class conflict between capitalists and workers but rather the more elemental conflict between men and women.

The women’s movement that emerged alongside the labour movement at the end of the century shared many of its assumptions. Early feminists such as Louisa Lawson dwelt, as did early socialists, on the progressive character of Australian society. They celebrated the egalitarianism of Australian men and the comparatively good position of women. They also regarded Australia as free of the Old World evils of class, poverty or violence, and correspondingly free to explore novel possibilities. Just as local republicans drew on American precedents, agrarian radicals on the ideas of Henry George and socialists on the writings of Edward Bellamy, so the women’s movement was strongly influenced by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, which crossed the Pacific in the early 1880s. The movement sought to advance women and reform society by purifying domestic and public life of masculine excess. It thus pursued a range of measures – temperance, laws against gambling, control of prostitution, an increase in the age of consent, prevention of domestic violence – to protect women from predatory men. Conscious of their lack of political power, these women campaigned for female suffrage, and between 1894 and 1908 they won the right to vote for the national and every colonial legislature.

The leaders of this suffrage movement were educated and independent women. Rose Scott in Sydney, the elegant daughter of a Hunter Valley pastoralist, and Vida Goldstein in Melbourne, whose mother’s family were substantial landowners, acquired organisational skills in public philanthropy that they then applied to the cause of sexual emancipation. For both of them it was a full-time activity that precluded marriage and motherhood. Mary Gilmore explained her own lapse from participation in the campaign as the consequence of domesticity:

There were strains, also, between the feminists of the labour movement, who sought a more equal partnership to redeem the working-class family from hardship, and the more assertive modernism that would remove familial impediments to autonomy. Higher education, professional careers, less constrictive clothing and even the freedom of the bicycle were among the hallmarks of the ‘new woman’.

The appearance of the new woman signalled a contest as fierce in its conduct and far-reaching in its consequences as that fought out between labour and capital. It did not give rise to a new political party, and all early attempts by women to win parliamentary representation failed, for the sex war was fought on a different terrain. The leader of the Labor Party announced in 1891 that his comrades had entered the New South Wales legislative assembly ‘to make and unmake social conditions’; the women’s movement stayed out of parliament to remake the family and sexual conditions. In both cases a fierce assault brought home the illusory character of customary expectations. A heightened consciousness of distinctive interests produced a movement that sought to recover just entitlements with novel demands. The labour movement fought for the rights of labour, the women’s movement for control of women’s bodies.

An infamous rape case in 1886 on wasteland at Mount Rennie in Sydney, close to the site of the Centennial Park, served as the Jondaryan incident in this contest between the sexes. A sixteen-year-old orphan girl searching for work was waylaid by a cab driver, taken there and pack-raped by eighteen youths. There was an upsurge in such crimes in the 1880s, suggestive of heightened sexual tension, and they involved young men known as larrikins, distinctive in their flash clothing and brazen defiance of authority. ‘We seldom get through a march without being covered in flour or eggs’, complained an officer of the Salvation Army in 1883.

Larrikin pushes formed in the inner industrial suburbs, comprising both boys and girls who worked in casual, unskilled employment. Occupations such as street-selling, scavenging and running messages, which exposed youths to the temptations of the city, aroused middle-class fears that the city was being taken over by the most bestial forms of humanity. The Mount Rennie rapists were prosecuted, four hanged, and seven others sentenced to hard labour for life. A Methodist minister regarded the outrage as evidence of the ‘vile lowering tendencies’ of Australian youth; the defiant Bulletin insisted that ‘if the prisoners’ deed deserved so frightful a penalty, where is there “a man of the world” who would go unwhipped?’ The Mount Rennie case was as unusual and as controversial as the Myall Creek case fifty years earlier.

Those who sought to curb the animal instincts of men extended their campaign to crimes against women within the home. From denouncing the evil of domestic violence they moved to question the very basis of marriage as a trade in sexual labour, and to demand that women should have control over their fertility. Here they were swimming with the demographic tide – there was a marked decline in marriage during the depression decade, and an even sharper decline in reproduction – though that did not prevent the men who conducted a royal commission on the birthrate in 1903 from blaming women for neglecting their national duty as breeders and domesticators.

Women had an effective response to that accusation. The interests of the nation would best be served by ensuring that children were born voluntarily and raised in homes purged of men’s irresponsibility and excess. It was for this reason that feminists sought to restrain the men who frittered their earnings on gambling, tobacco and alcohol, and returned from the pub to tyrannise their dependents. Masculinity had to be tamed of its selfish, aggressive qualities in order for the lone hand to be brought to his duty as a reliable breadwinner and helpmate. Femininity had to be heeded for its superior moral status to purify the family circle and exalt national life. Not all Australian feminists followed this domestic logic to its extreme conclusion of separate spheres. They still argued for women’s rights of education, employment and public participation. They also created their own voluntary associations that infused civic life with nurturing maternalist values celebrated by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union:

The contest between the sexes at the turn of the century did not displace men from positions of dominance in politics, religion and business, but it decisively altered their prerogatives.

***

The labour and the women’s movements were movements of protest. With the end of an era of uninterrupted growth, the belief in progress faltered. The failure of existing institutions to maintain harmony fractured the liberal consensus. An optimism grounded in common interests and shared values yielded to disillusionment and conflict. Socialists and feminists called on the victims of oppression to rise up against the masters and men who exploited and abused them. The goal was to reconstruct society and heal the divisions of class and gender; the effect was to mobilise powerful collectivities with separate and distinctive loyalties – socialism and feminism were universal in scope and international in operation. In response to these challenges an alternative collectivity was asserted: that of the nation. It was institutionalised during the 1890s through a process that produced a federal government with restricted powers, but behind that limited compact lay the stronger impulses of tradition and destiny. Out of the crisis of colonial coherence, a binding Australian nationhood was created.

Australians can hardly be accused of rushing into federation. The process can be dated back to the early 1880s, when the designs of the French and Germans in the southwest Pacific alarmed the colonies, but New South Wales’ suspicion of Victoria prevented anything more than a weak and incomplete Federal Council. In 1889 the aged and previously obstructive premier of New South Wales, Henry Parkes, made a bid for immortality as the father of Federation by issuing a call for closer ties. That brought representatives of the colonial parliaments to a Federal Convention in Sydney in 1891. They drafted a constitution, but their colonial parliaments failed to approve it.

Edmund Barton and Alfred Deakin were the leaders of the federal movement in New South Wales and Victoria, and the first two prime ministers of the new Commonwealth. Barton sits on the left in the marmoreal dignity, while Deakin’s informal pose suggests a more mercurial temperament.

Federation revived when the colonies authorised the direct election of delegates to a new convention and agreed in advance to submit its proposals to popular referendum. The second Federal Convention met from 1897 to 1898, but only the four southeast colonies proceeded to referenda and only three produced the necessary affirmative vote. Further concessions were required before New South Wales did so in a second referendum and the outlying colonies of Queensland and Western Australia joined in. The proclamation of the Commonwealth on 1 January 1901 in Centennial Park, Sydney, came more than a decade after Parkes had appealed to ‘the crimson thread of kinship’.

For Alfred Deakin, the leading Victorian who pursued union as a sacred duty and prayed frequently for the fortunes of Federation, ‘its actual accomplishment must always appear to have been secured by a series of miracles’. For Edmund Barton, the champion in New South Wales and the first national prime minister, the winning of ‘a nation for a continent and a continent for a nation’ was a surpassing achievement. It touched the easygoing Barton as no other cause, and when he launched the Yes campaign in the first referendum he declared that ‘God means to give us this Federation’.

If Federation was sacred, it was not beholden to organised Christianity. Cardinal Patrick Moran, the Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, provoked fierce Protestant opposition when he stood for the Federal Convention. The convention did bow to a torrent of church petitioners and acknowledge in the preamble to the constitution that the people were ‘humbly relying on the blessing of Almighty God’ when they formed their Commonwealth, but section 116 of that constitution excluded any establishment of religion. Moran withdrew from the ceremony inaugurating the Commonwealth because the Anglican primate had precedence in the procession.

The constitution blended the British system of responsible government with the American model of federalism: the colonies (henceforth States) assigned certain specified powers to a bicameral national parliament, the House of Representatives representing the people and the Senate the States, with the government responsible to the popular lower house. Much of the protracted federal debate was taken up with enumerating those powers and balancing the fears of the less populous States with the ambitions of the more populous ones. All of the States made elaborate calculation of the effect of the union on their own fortunes. Merchants, manufacturers and farmers considered how they would fare when Australia was turned into a common market. As Deakin recognised, ‘Few were those in each colony who made genuine sacrifices to the cause without thought or hope of gain.’

Nor did the colonists wrest independence from imperial control. During this period the British government encouraged the settler colonies of Canada, New Zealand, Australia and South Africa to amalgamate into more coherent and capable dominions, self-governing in their internal affairs while consistent in their imperial arrangements. The new designation, Dominion, was adopted in 1907 at a colonial conference in London that determined these gatherings would henceforth be known as imperial conferences. So London fostered Australian federation, the Colonial Office shaped its final form, and the Commonwealth constitution took legal force as a statute of the British parliament.

That fact alone alienated local republicans, while the process of Federation was initiated too early for members of the labour or women’s movement to participate and shape it. In contrast to the earlier confederations of the United States and Germany, Australia undertook no war of independence or incorporation. Unlike the Italians, it experienced no Risorgimento. The turnout in the federal referenda was lower than for parliamentary elections; in only one colony, Victoria, and that narrowly, did a majority of eligible citizens cast their votes in favour of Federation.

Yet for the federal founders and for those present-day patriots who would revive the civic memory, those plebiscites were all-important. They installed the people as the makers of the Commonwealth and popular sovereignty as its underlying principle – a principle the courts have now come to recognise in their interpretation of the constitution. According to this view, the politicians had been entrusted with the national task but botched it. The work of the first Federal Convention of 1891 languished in the colonial parliaments. Then came an unofficial gathering in 1893 at the Murray River town of Corowa, on the New South Wales-Victoria border, of representatives of local federal leagues and branches of the influential Australian Natives Association, a voluntary society restricted to those born in the country. The gathering devised the alternative procedure that would bring success: the people themselves would elect the makers of a new federal arrangement, the people would adopt it, the people would be inscribed in its preamble and included in the provisions for its amendment. This was a unique achievement. In the words of one celebrant, it was ‘the greatest miracle of Australian political history’.

Perhaps it was, but it was also expressive of national prejudices. The unofficial gathering at Corowa was orchestrated by politicians. The man who proposed the new approach there and enunciated the principle ‘that the cause should be advocated by the citizen and not merely by politicians’ was himself a politician. All but one of the delegates elected to the second Federal Convention had parliamentary experience; two-thirds had ministerial experience, a quarter as premiers. Federation was an inescapably political act but one that Australians, with their disregard for politics, preferred to see otherwise.

These people were Australians but that national identity was itself undergoing reconstruction. The new nation was shaped by external threat and internal anxiety, the two working together to make exclusive racial possession the essential condition of the nation-state. The external threat came initially from rival European powers. France, Germany, Russia and now the United States and Japan were expanding their overseas territories. The Australian colonies, which had their own sub-imperial ambitions in the region, pressed Britain to forestall the interlopers, but Britain was already feeling the strain of its imperial burden.

The maintenance of the British Empire absorbed an increasing effort. As Britain faced sharper competition from the ascendant industrial economies, it turned to easier fields in its colonies and dominions. But cheap colonial produce, ready Dominion markets and lucrative careers in imperial administration imposed their own cost. A free-trade empire required a large military expenditure and the cost of the Royal Navy constituted an effective levy on the cheap imports that sustained the workshop of the world. That cost increased as European powers stepped up the pace of the arms race and Britain was forced to concentrate more of its naval strength closer to home.

It therefore expected its settler Dominions to become more self-sufficient. In 1870 it had withdrawn the last garrisons from Australia, leaving the colonies to raise their own troops; an adverse British report in 1889 on the capacity of these militia forces was one stimulus for Federation. The Royal Navy remained as the final guarantor of Australian security, and forts constructed at the entrance of major ports were meant to hold off an attacking force until relief arrived. In 1887, the colonies agreed to meet part of the cost of a British squadron in Australian waters.

If the Empire no longer extended to the antipodes as securely as the nervous settlers wanted, they must offer themselves in its overseas service. They had begun to do so in the 1860s as volunteers alongside British troops and pakeha in a war against the indigenous Maori. Their next act of assistance, to a British expeditionary force in Sudan in 1885, was insubstantial and inglorious. The contingents sent to South Africa between 1899 and 1902 was more substantial – 16,000 Australian troops assisted the British in putting down Dutch settlers there – but scarcely earned martial glory. Again in 1900 the colonies sent a contingent to China to assist the international forces quell a rebellion against the European presence. All four of these overseas wars, it should be noted, began as local risings against foreign control and in all four the Australians fought on the imperial side against national independence.

The last of them was the least remarked and probably the most eloquent of Australian fears. By the early twentieth century the premonition of a new, awakening Asia displaced Europe as the source of military threat in the national imagination. A rash of invasion novels appeared at this time in which the country was no longer besieged by French or Russian battleships but rather overrun by hordes of Orientals. The fear was fed by the growing power of Japan, which imitated Western economic and military techniques to defeat China and occupy Korea in 1895. An Anglo-Japanese treaty in 1902, which allowed Britain to reduce its own naval strength in the Pacific, increased the Australian concern.

The Japanese navy’s destruction of a Russian fleet in 1905 increased it further. Thwarted in his efforts to increase the British presence in the Pacific, Alfred Deakin as prime minister invited the ‘Great White Fleet’ of the United States to visit Australia on its global voyage in 1908. A popular verse captured the sentiment:

In the following year Australia decided to acquire its own fleet and in 1910 it introduced compulsory military training.

More than this, the Australian fear of invasion played on the Asian presence in Australia. There had been earlier explosions of racial violence, most notably against the Chinese on the goldfields, though their enterprise brought success and substantial community acceptance. Antagonism revived in 1888 with the arrival of a vessel from Hong Kong carrying Chinese immigrants who were turned away under threat of mob action from both Melbourne and Sydney. The controversy touched national sensitivities since Hong Kong was a British colony, and the Colonial Office was antagonistic to immigration restriction based on overt racial discrimination. For nationalists, the alien menace therefore served as a reminder of imperial control; hence the adoption by the Bulletin in this same year of the slogan ‘Australia for the Australians’. For trade unionists, the Chinese were cheap labour and a threat to wage standards. For ideologues such as William Lane, they were sweaters and debauchers of white women. Even the high-minded Alfred Deakin judged that the strongest motive for Federation was ‘the desire that we should be one people, and remain one people, without the admixture of other races’.

Yet racial exclusion did not require a break with Britain, nor did it rely on Commonwealth legislation. Racism was grounded in imperial as well as national sentiment, for the champions of the Empire proclaimed the unity of the white race over the yellow and the black. Charles Pearson affirmed a white brotherhood in a global survey of race relations to claim that ‘we are guarding the last part of the world in which the higher races can live and increase freely for the higher civilization’. Pearson, a costive English intellectual who migrated to Australia for his health and practised both education and politics with a melancholic rectitude, sounded the alarm in a book that he proposed to call Orbis Senescens – for he was convinced that civilisation was exhausting the vitality of the European peoples.

His London publisher thought that title too gloomy so it appeared in 1893 as National Life and Character: A Forecast, and impressed the future American president Theodore Roosevelt with the urgency of its warning. Alfred Deakin, Pearson’s former pupil, shared his fears and claimed the visit of the Great White Fleet showed that ‘England, America and Australia will be united to withstand yellow aggression’. Australians did not invent this crude xenophobic terminology – it was, after all, an imperial bard who warned of ‘lesser breeds without the law’ – but their inclination to overlook the multiracial composition of the Empire was a domestic indulgence that only a dutiful Dominion could afford.

In 1897 the Colonial Office persuaded the Australian premiers at a conference in London to drop explicit discrimination against other races in favour of an ostensibly non-discriminatory dictation test for immigrants, a device used by other British Dominions to achieve the same result. Since a foreigner could be tested in any European language, the immigration official need only select an unfamiliar one to ensure failure. This was the basis of the Immigration Restriction Act passed by the new Commonwealth parliament in 1901, but by then Asian immigration was negligible. White Australia was not the object of Federation but rather an essential condition of the idealised nation the Commonwealth was meant to embody.

Deakin spelt it out during the debate on the Immigration Restriction Act:

The unity of Australia is nothing, if that does not imply a united race. A united race means not only that its members can intermix, intermarry and associate without degradation on either side, but implies one inspired by the same ideas, an aspiration towards the same ideals, of a people possessing the same general cast of character, tone of thought …

The founding conference of the federal Labor Party adopted White Australia as its primary objective; in 1905 it provided the rationale with its commitment to ‘The cultivation of an Australian sentiment based upon the maintenance of racial purity and the development in Australia of an enlightened and self-reliant community’.

Ideals, character, tone of thought, sentiment, enlightenment, self-reliance, community. These virtues sound as desirable at the beginning of the twenty-first century as they were at the beginning of the last. The dissonance comes from their association with racial exclusiveness. We might better grasp their plausibility if we transfer them from race to culture. Our recognition of other ethnic groups, and respect for their language, beliefs and customs, is a pluralist one purged of biological undertones of genetic determinism, but we still expect their subordination to a shared and binding culture.

White Australia was therefore an ideal, but it was also a falsehood. The Immigration Restriction Act was used to turn away non-European settlers, but it left substantial numbers of Chinese, Japanese, Indians and Afghans already here. Commonwealth legislation passed in 1901 provided for repatriation of Pacific Islanders from the Queensland sugar industry, but long-term residents were allowed to stay as the result of protests. New immigrants from Java and Timor were allowed to enter the pearling industry. Non-European traders, students and family members continued to land at Australian ports. Since racial uniformity was an illusion, the promise of equality was also a lie. Discriminatory laws denied naturalisation to non-Europeans, excluded them from welfare benefits, shut them out of occupations, and in some States refused them land tenure.

The impact of these policies was especially marked in northern Australia. The population living above the Tropic of Capricorn at the turn of the century was about 200,000. Half were Europeans, though they were concentrated in the Queensland ports of Townsville, Mackay and Cairns, and the mining town of Charters Towers, and elsewhere showed little sign of increase. Some 80,000 were indigenous, mostly in the vast hinterland, and another 20,000 were Asians and Pacific Islanders. Europeans constituted but a small minority in the thriving multiracial communities of Broome, Darwin and Thursday Island, off the tip of Cape York, which did more business with Hong Kong than any Australian city.

It was the southern visitor who found the multiracial north so shocking. A contributor to the Sydney Worker complained how he was forced to travel with ‘two Chows, one Jap, six kanakas’ on his passage to Cairns. A correspondent to the Bulletin wrote in disgust of the situation at Townsville with ‘kanakas on sugar plantations … blacks and Chows on stations, Chows as gardeners, storekeepers, laundry-keepers and contractors’. He concluded with the magazine’s slogan, ‘Australia for the Australians!’

An historian attuned to the differences has observed that when Australia federated in 1901, ‘there were two Australias: North and South’. The South had evolved a successful model of a racially homogenous developmental state that nurtured export-oriented farming and urban manufacturing. The North presented more demanding geographies, more limited opportunities for investment and a sparser, diverse population. The South sought to colonise the North by extending its model of economic development and social integration. But when it ended the recruitment of Pacific Island labourers and closed the door to Asians, it was unable to attract investment to the north or to incorporate the remote Aboriginal communities into the market for goods and labour. The Indigenous people thus remained outside the settler nation.

They were absent from the ceremonies that marked the advent of the Commonwealth. And they were eliminated from the art and literature that served the new national sentiment. While earlier landscape painters had frequently incorporated groups of natives to authenticate the natural wilderness, the Heidelberg school removed them to attach the white race to its harsh and elemental patrimony. Aborigines were even deprived of their indigeneity by the members of the Australian Natives Association, who appropriated that term for the locally born Europeans. Yet they remained to discomfort the white conscience. Compassion came more readily to the usurper than acceptance, as fatalism lightened the burden of charity. Earlier humanitarians had been prepared to ease the passing of those they had wronged. In gloomy anticipation they proclaimed a duty to smooth the pillow of the dying race.

Now, as Darwinian science displaced evangelical Christianity and natural law as a source of authority, the scientist provided new confirmation of this forecast. Seen from the perspective of evolutionary biology, Australia had been cut off from the process of continuous improvement brought about by the competition for survival, and constituted a living museum of relic forms. Separated by such a wide gulf from the march of progress, its original people were incapable of adaptation and therefore doomed to extinction.

Census data seemed to support this theory. They presented a downward trend, to just 67,000 Aboriginal natives in 1901. But several of the States failed to enumerate all their Aboriginal inhabitants, and the Commonwealth constitution excluded them from the national census (so that their numbers would not be used for purposes of electoral representation). More than this, the State counts excluded a significant proportion of the Aboriginal population that was incorporated, albeit on the margin of the social and economic arrangements in the south – in effect, the government confirmed the expected disappearance of the indigenous people by defining these ones out of existence.

Again, the process enlisted science to validate coercion. Between 1890 and 1912 every State government took over what remained of the mission settlements by making Aborigines wards of the state. New agencies, usually called protection boards, were empowered to prescribe their residence, determine conditions of employment, control marriage and cohabitation, and assume custody of children. The actual use of these powers varied – Queensland and Western Australia, with the largest Aboriginal populations, had the most extensive reserves and settlements and the most authoritarian regimes – and many Aborigines minimised their exposure to them. The forcible separation of children from parents ensured that.

In this horrifying practice the government drew on the doctrine of race as a genetic category. While Aborigines were held incapable of supporting themselves, those born of Aboriginal and European parents were believed to possess a greater capacity. If denied assistance and removed from the reserves, they might be expected to support themselves and within a couple of generations even produce progeny no longer recognisably Aboriginal. It would thus be possible to reduce or close down the reserves as the residual numbers held there declined. In making these judgements the protectors employed a vocabulary of ‘full-blood’, half-caste’, ‘quadroon’ and ‘octoroon’; more often they worked by estimations of degrees of ‘whiteness’, which was taken as synonymous with capacity and acceptability. They did not encourage miscegenation, and several of the protectors insisted that their staff must be married men, but once it occurred they believed it would ‘breed out’ the Aboriginal blood.

Such a programme was beset by contradictions. Ostensibly protective, the settlements and missions were premised on the demise of their residents. Others, on the other hand, were forcibly evicted and expected to interact and intermarry with non-Aboriginals. In sharp contrast to other white-supremacist settler societies, there was no uncrossable barrier between black and white, for Australia’s policy inverted the logic of racial separation that operated in the United States. All of this was premised on the elimination of Aboriginality, the abandonment of language, custom and ritual, and the severing of kinship ties so that absorption could be complete.

It was an impossible condition, and for many present-day Aborigines it constitutes a policy of genocide. So it was in the literal sense, except that the genes were to be diluted rather than eliminated by mass execution in the manner made infamous by the Holocaust. The more common accusation is of cultural genocide, meaning the destruction of a distinctive way of life, and that undoubtedly was intended; though it is a further irony that the scientists who justified this objective were also the collectors and recorders of Aboriginal culture who made it possible for some of the Aboriginal survivors to reclaim that culture as their own.

The proclamation of the Commonwealth on the first day of the new century fused national and imperial ceremony. In a competition to design a national flag that drew 32,000 entries, five people shared the prize by imposing the British one on the corner of a Southern Cross; though the Union Jack remained the official flag until 1950. A coat of arms, supported by a kangaroo and emu, also had to wait until 1908, backed after 1912 by two sprays of wattle. First the Test cricket team and then other sporting representatives adopted the green and gold of the gum tree and the wattle as the national colours.

Australian flora and fauna were popular decorative motifs in the Federation period, with the wattle to the fore as an Australian equivalent of the Canadian maple. The golden wattle went with golden fleece, golden grain, golden ore and the gold in the hearts of the people. According to the Wattle Day League, it stood for ‘home, country, kindred, sunshine and love’. But Empire Day had been introduced some years earlier as part of a conscious strengthening of imperial links. Nationalism and imperialism were no longer rivals. You could, as Alfred Deakin described himself, be an ‘independent Australian Briton’.

Britain provided this continental nation-state with a portion of its own imperial responsibilities when it handed over its portion of New Guinea as the Commonwealth territory of Papua in 1902. South Australia did the same with the Northern Territory in 1911 and Australians were already active in Antarctic exploration, paving the basis for its subsequent claim to two-thirds of the southern land of ice. Meanwhile federal parliamentarians selected a site for a national capital on a grassy plain in the high country between Sydney and Melbourne and the members of the Cabinet considered various names for it: Wattle City, Empire City, Aryan City, Utopia. In the end they settled on a local Aboriginal word, Canberra.

An American architect, Walter Burley Griffin, won the competition to design the capital. He conceived a garden city with grand avenues linking its governmental and civic centres, and concentric patterns of residential suburbs set in forest reserves and parks. But bureaucrats hampered the execution of his design, which was still incomplete in 1920 when responsibility was transferred to a committee. Melbourne, a monument to nineteenth-century mercantile imperialism, remained the temporary national capital for the first quarter of the twentieth century.

The Australian nation was shaped by the fear of invasion and concern for the purity of the race. These anxieties converged on the female body as nationalist men returned obsessively to the safety of their women from alien molestation, while doctrines of racial purity, no matter how scientific, rested ultimately on feminine chastity. Women participated in this preoccupation with their own maternalist conception of citizenship, which took emancipation from masculine tyranny as a necessary condition of their vital contribution to the nation-state. A woman’s personal and bodily integrity thus served as a further condition of her admission to civic status, as in the Commonwealth legislation in 1902 that gave all white women the vote. But the same legislation disenfranchised Aborigines, who were deemed to lack both the autonomy and the capacity to make such a contribution.

These trademarks for soap, wine, poison, sporting goods and baking powder were all devised in the early years of the twentieth century when the new nation fashioned native symbols.

Some feminists regretted this Faustian compact, just as they criticised the treatment of Aboriginal women who were subjected to sex slavery of a particularly clear and offensive nature. The vulnerability of Aboriginal women to white predators and the denial of their children, the very devices that were expected to bring about a White Australia, were for these white women intolerable iniquities against the institution of motherhood. Here again maternalist citizenship was at odds with the masculine nationalism proclaimed by the Bulletin when in 1906 it changed its slogan ‘Australia for the Australians’ to ‘Australia for the White Man’.

***

White Australia, Alfred Deakin stated in 1903, ‘is not a surface, but a reasoned policy which goes to the roots of national life, and by which the whole of our social, industrial and political organisation is governed’. He spoke as leader of the Protectionist Party, which held government with the support of the Labor Party. There were three parties in the national parliament until 1909 – Protectionist, Free Trade and Labor – and none commanded a majority. Except for a brief interval, the Protectionists and Labor alternated in office with the qualified support of the other and a sufficient measure of agreement on policy to cause the Free Traders to rename themselves the Anti-Socialists for the 1906 election, though with no greater success. The social, industrial and political forms of the new Commonwealth were therefore worked out by a consensus that spanned the manufacturing interests and progressive middle-class followers of protectionist liberalism with the collectivism of the organised working class.

The task undertaken by these political forces was to restore the prosperity lost in depression and drought, heal the divisions opened by strikes and lockouts, and reconstruct a settler society to meet the external and internal dangers to which it felt itself vulnerable. The external threats – strategic, racial and economic – were also internal, foreshadowing loss of sovereignty, degradation, poverty and conflict. The search for security and harmony produced a coherent programme of nation-building.

Some of the elements of this programme have already been described. The threat of invasion was met by military preparations within the framework of imperial protection. While Australia felt it necessary to assert its own interests in imperial forums, the intention was always to ensure that London was conscious of the needs of its distant Dominion: the independence of ‘independent Australian Britons’ was premised on the maintenance of the Empire. Australia relied on the Royal Navy not just to defend its shores but to keep open the sea routes for trade. Three-fifths of its imports came from Britain, half its exports went there. British finance underwrote the resumption of growth in the early years of the new century as the pastoral industry was reconstructed and the agricultural frontier expanded.

The fear of racial mixing was met with the White Australia policy, which closed Australia to Asian immigration. But the regime of migration control was more than simply exclusionary. Overseas labour recruitment, along with foreign investment in public projects and private enterprises, was a motor of growth. Immigration resumed in the times of prosperity that returned by the end of the first decade. Forty thousand British settlers were assisted to come to Australia between 1906 and 1910; 150,000 more between 1911 and 1914, when the population passed 4.5 million. Conversely, migrants were discouraged when unemployment was rife and new entrants had a depressive effect on the labour market: there were fewer than 4000 assisted settlers between 1901 and 1905. The counter-cyclical pattern of government migration activity helped secure the labour movement’s acceptance of this aspect of nation-building.

Jobs were also safeguarded by tariff duties on imports that competed with Australian products. This arrangement secured the alliance of the Protectionist and Labor parties, representing the manufacturers and their workers. By the time that alliance lapsed and the Protectionist and Free Trade parties merged in 1909 to create the Liberal Party in order to combat the growing success of the Labor Party, the tariff (with lower duties on imperial products) was a settled feature of national policy. Protection allowed local producers to expand their output and increase manufacturing employment from less than 200,000 in 1901 to 330,000 by 1914. The Commonwealth’s protection of local industry had a novel dimension: it was available only to employers who provided ‘fair and reasonable’ wages and working conditions. As Deakin explained, ‘The “old” Protection contented itself with making good wages possible’, but the New Protection made them an explicit condition of the benefits.

The determination of a fair and reasonable wage was the task of the Commonwealth Arbitration Court, which was an additional component of the national programme. The endemic conflict between employers and unions was to be resolved by a legal tribunal with powers to arbitrate disputes and impose settlements. Several States had created such tribunals in the aftermath of the strikes and lockouts of the 1890s, and the federal one was established in 1904 after prolonged parliamentary argument. In 1907 it fell to its president, Henry Bournes Higgins, to ascertain the meaning of a fair and reasonable wage in a case concerning a large manufacturer of agricultural machinery.

Higgins determined that such a wage should be sufficient to maintain a man as a ‘human being in a civilized community’; furthermore, since ‘marriage is the usual fate of adults’, it must provide for the needs of a family. He therefore used household budgets to work out the cost of housing, clothing, food, transport, books, newspapers, amusements, even union dues, for a family of five, and declared this a minimum wage for an unskilled male labourer. It took some years to extend this standard (which became known as the basic wage and was regularly adjusted for changes in the cost of living) across the Australian workforce, but the principles of Higgins’ Harvester judgement became a fundamental feature of national life. Wages were to be determined not by bargaining but by an independent arbitrator. They were to be based not on profits or productivity but human need. They were premised on the male breadwinner, with men’s wages sufficient to support a family and women restricted to certain occupations and paid only enough to support a single person. Women contested the dual standard for the next sixty years.

Around these arrangements a restricted system of social welfare was created. The great majority of Australians was expected to meet their needs through protected employment and a legally prescribed wage. They were also expected to provide for misfortune through accident or illness: Higgins’ basic wage included the cost of subscription to a voluntary society, which offered coverage for medical costs and loss of earnings. It was recognised that some were not so provident – and State governments supported the private charities – but dependence was discouraged and self-sufficiency a hallmark of masculine capacity. That many mothers were denied the benefit of a husband’s earnings was recognised only in the restriction of charitable assistance to women and children; for a man to accept a handout was to forfeit his manliness.

To this logic of the male breadwinner special cases were allowed where the state offered direct assistance: the old-age pension, from 1908, and an invalid pension, from 1910, for those outside the workforce, and a maternity benefit, from 1912, to assist mothers with the expense of childbirth. Australia came early to the payment of benefits for welfare purposes, but it stopped short of the general systems of social insurance developed in other countries where the operation of the labour market imperilled social capacity. Rather, Australia provided protection indirectly through manipulation of the labour market in what one commentator has described as a ‘wage-earners’ welfare state’.

Such were the components of a system that was meant to insulate the domestic economy from external shocks in order to protect the national standard of living. Contemporaries took great pride in its generous and innovatory character. Social investigators came from Britain, France, Germany and the United States to examine the workings of this ‘social laboratory’ that had apparently solved the problems of insecurity and unrest. Seen from an early-twenty-first-century vantage point, as its institutional forms were dismantled, it was judged more harshly. An economic historian suggests that a system of ‘domestic defence’ meant to provide protection from risk lost the capacity for ‘flexible adjustment’ and innovation. A political commentator sees the ‘Australian Settlement’ as a premature lapse into an illusory certainty that left ‘a young nation with geriatric arteries’.

These judgements are anachronistic. The critics construe the national reconstruction as one that sacrificed efficiency to equity and blame it for slowing the country’s economic growth. But Australia had already lost more than a decade of growth as the result of depression and drought, so that the tariff, arbitration and the basic wage can hardly be blamed for the slowdown. The makers of the Commonwealth sought to modify the market to create national mastery of material circumstances, to weld a thinly peopled continent with distant centres and regional differences into a secure whole, and to regulate its divergent interests to serve national goals. That was not simply a defensive or protective project; it was an affirmative and dynamic one.

This can be seen in the impressive record of technological innovation. Colonial Australians had cultivated the reputation of improvisers. The rule of thumb prevailed over formal knowledge and the mechanics’ institutes and schools of mines were more closely attuned to industrial needs than the fledgling universities. By the end of the century there was an enhanced scientific effort. Miners found improved methods of extracting minerals; the flotation process developed at Broken Hill was copied around the world. Farmers used fertilisers and new wheat varieties to extend into the low rainfall zones beyond the Great Diving Range and out onto Western Australia’s inland wheatbelt. The locally produced mechanical harvester that gave rise to the basic wage was as advanced as the ones used on the North American plains. Governments built substantial irrigation works to support more intensive horticulture and diversify the country’s rural exports.

Factories, shops and offices were quick to embrace new machines and techniques that increased productivity. Australians took up the pocket watch, the typewriter and the telephone with the enthusiasm they showed later for the personal computer. This, moreover, was a society that was equally innovatory in its leisure: from the 1880s the Saturday half-holiday became common and a biblical division of the week into six days and one gave way to five and two. Australians might not have invented the word ‘weekend’ but they certainly made good use of it.

They were quick also to adopt the gospel of efficiency. The striving for improvement in every corner of national life accorded with the new understanding of progress, no longer as the fruits that came from planting civilisation in an empty continent but as a conscious task of national survival in an uncertain, harshly competitive world. ‘The race is to the swift and strong, and the weakly are knocked out and walked over’, warned a leading businessman. Thus employers applied the methods of scientific management to industry through simplification of the labour process, careful measurement of each task and close supervision of its performance.

The domestic market was too small for these techniques to be applied fully to any but the biggest companies, and their impact was probably greater in public enterprises, such as the railways, and major government departments, which dwarfed private sector organisations in scale and complexity. Vast engineering projects were required to construct underground sewerage systems for the principal cities. Both federal and State governments expanded to take on new tasks, administrative, infrastructural, financial, industrial and even commercial. Public transport, communication, gas, electricity, banks, insurance, and coalmines, timberyards, butchers, hotels and tobacconists when the Labor Party held office, provided essential services, checked profiteering and acted as pacesetters for wages and conditions.

Beyond industrial and administrative efficiency lay the goal of social efficiency. This was pursued through a range of reforms aimed at reinvigorating the race and strengthening its capacity to contribute constructively to national goals. The reformers were modernists, seized with the pace of change and the powerful currents that ran through human conduct, and they were experts, confident that they could harness the creative impulse and instil purposeful order. They were concerned with the ills of modernity: the slum, the broken home, social pathology, degeneracy. They worked through professional associations and voluntary bodies, and they embedded their plans in public administration. They styled themselves progressives, after the American progressivist movement on which they drew. Progressivism found application in town planning and national parks, community hygiene, ‘scientific motherhood’, kindergartens, child welfare and education. The New Education replaced the old rote learning with an emphasis on individual creativity and preparation for the tasks of adulthood: manual skills, nature study, health and civics, to promote an ethic of social responsibility.

The Australian Settlement, then, was not a settlement. The reconstruction of the Australian colonies came in response to challenges that jolted established arrangements and assumptions. In their search for security the colonists adopted the forms of the race and nation, both artefacts of the modern condition of uncertainty and constant change. White Australia bound the country more tightly to Britain. At a time when the United States was taking in the huddled masses of Europe, and Canada too accepted immigrants from east and south Europe, Australia restricted its intake to the old country. It was more monolingual by 1914 than ever before.

With British stock as the basis of a new nation came the problems of dependence and economic vulnerability, the old quarrels over rank and religion, and further ones over class and gender. William Lane had sought to preserve the innocence of the New World with his New Australia, a forlorn endeavour. Alfred Deakin used New Protection to provide a measure of autonomy and harmony. But the New World was tethered to the old and could not escape its effects.