The end of the war released a pent-up demand for goods and services that had long been unavailable, yet the task converting a war economy back to peace conditions called for continuing restraint. In asking voters for patience during the 1946 election, Ben Chifley assured them of the benefits that would flow. ‘Australia was entering a golden age’, he said. With so many chafing at the shortage of housing and household goods, the opposition derided the prime minister’s claim, but he was vindicated. The third quarter of the twentieth century was an era of growth unmatched since the second half of the nineteenth century. The population almost doubled, economic activity increased more than threefold. There were jobs for all men who wanted them. People lived longer, in greater comfort. They expended less effort to earn a living, had more money for discretionary expenditure, greater choice and increased leisure.

Sustained growth brought plenty to Australians and habituated them to further improvement: a belief in the capacity of science to turn scarcity into abundance was matched by the confidence that planners could guide prosperity and experts use it to solve social problems. The facilities of intellectual life and the possibilities for artistic creativity expanded. The country became less isolated from the rest of the world and less beleaguered in its domestic arrangements. But as the ancients discerned a cyclical pattern of history, which saw the purposeful vigour of an ascendant civilisation soften into indulgence, disunity and eventual collapse, so post-war Australia followed a worrying trajectory. The iron age of austerity occupied the 1940s; the 1950s were the silver years of growing confidence and comfort; by the golden 1960s indulgence and decay had set in, and the regime could not withstand the discordant forces it had released.

This might be too parochial a perspective. The long boom of the 1950s and 1960s was an international phenomenon, the fruits of prosperity shared by all advanced economies. As a trading country, Australia benefited from the revival of world trade and investment, shared in the new technologies, followed the same techniques of management and administration. As a junior partner of the Western alliance it was also caught up in the Cold War with the Communist bloc and drawn into military commitments that ended by the 1970s in overextension and humiliation just as the golden age of plenty ran out. Decision-makers would never again enjoy such luxury of choice or feel the same confidence. Some looked back on the post-war period as an era of strong leadership and responsive endeavour; others lamented the lost opportunities and timorous complacency.

***

The iron age spanned the production of weapons of war and the beating of swords into ploughshares. The wartime Labor government had assumed unprecedented controls over investment, employment, production, consumption and practically every aspect of national life. Planning for peace began at the end of 1942 with the appointment of a young economist, H. C. (‘Nugget’) Coombs, to direct the Department of Post-war Reconstruction. A railwayman’s son with a strong social conscience and a doctorate from the London School of Economics, Coombs was emblematic of the enhanced role of the planner.

His minister until 1945 was Ben Chifley, who was also the Treasurer and Curtin’s closest confidant. An engine-driver who had been victimised for his part in a strike during the First World War, Chifley was one of an older generation of stalwarts determined that after this war there would be no return to hardship and humiliation. He frequently recalled the degrading treatment of the working class during the Depression, when men were thrown on the streets and left to starve, forced to beg for jobs at factory gates, treated worse than pit-ponies in the mines. ‘I was not one of those who suffered want in those years’, he told parliament in 1944, ‘but it left a bitterness in my heart that time cannot eradicate’.

An austere man of simple dignity with a voice damaged by too many open-air addresses, and possibly his pipe, Chifley did not often venture on flights of rhetoric. Speaking to a Labor Party conference in 1949, however, he conjured a phrase for the goal that sustained him through half a century of service in the cause. It was not simply a matter of putting an extra sixpence in workers’ pockets, or elevating individuals to high office. Labor strove to bring ‘something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people’. Without that larger purpose, that ‘light on the hill’, then ‘the labour movement would not be worth fighting for’.

His government’s plans required the demobilisation of the armed forces and the return of workers from war production to peacetime employment. The munitions industries were to revert to domestic manufacture behind the traditional tariff wall, but with an enhanced scope and capacity. The government therefore gave the American General Motors Corporation generous concessions to establish a local car industry and the first Holden sedans rolled off the assembly line in 1948. The rural industries, badly run down after the pre-war decade of low prices and then the sudden demand for increased output, were to be modernised. Tractors replaced horses, and 9000 new soldier settlers were placed on the land. The shortage of skills was to be met by retraining ex-servicemen in technical schools and universities: the country’s lecture theatres were packed and an Australian National University was established as a centre of research. The backlog of demand for housing was to be filled with federal funding for State authorities: 200,000 homes were constructed between 1945 and 1949.

This spurt of state-sponsored development had a social as well as an economic aspect, for the war had augmented the call to ‘populate or perish’, and the Labor government embarked on the first major migration programme for two decades. In 1945 Arthur Calwell became Australia’s first minister for immigration. He set a target of 2 per cent annual increase in the current population of 7.5 million, half of which was to be contributed by new arrivals. The minister sought them in Britain but that country was no longer encouraging emigration, so Calwell turned of necessity to continental Europe, where millions of refugees had been uprooted by the abrupt shifts of national and political boundaries. In 1947 he toured the refugee camps and confirmed that they offered ‘splendid human material’, which moreover could be shipped to Australia at international expense and required to work for two years under government direction. Over the following four years 170,000 of these ‘Displaced Persons’ were brought to Australia, chiefly from the nations transferred from German to Soviet control in the corridor of eastern Europe that ran from the Baltic down to Aegean Sea.

Calwell also negotiated agreements with European governments to recruit additional migrants. His successor extended these arrangements in the early 1950s from northwest to south and east European countries. In that decade Australia received another million permanent settlers and most of them were non-British, with the largest contingents from Italy, the Netherlands, Greece and Germany. In 1947 the number of locally born Australians was at an all-time high of 90 per cent (with another 8 per cent from Britain or New Zealand). By 1961 the locally born dropped to 83 per cent. This decisive break with previous practice was confirmed by the creation of a separate citizenship in 1948 with provisions for those who were not British subjects to acquire the status of Australian citizen.

The migration programme, while maintained and expanded by the non-Labor government that took office at the end of 1949, was Labor’s. Calwell, a former trade union official deeply embedded in the lore of the labour movement, shared its national prejudices and occupational concerns. ‘Two “Wongs” do not make a White’, he declared in defence of his decision to deport Chinese refugees in 1947. Yet it was Calwell who coined the term ‘new Australian’ to encourage the assimilation of unfamiliar newcomers. The pressure on them to give up their ethnic identities in order to conform to ‘the Australian way of life’, another new locution, was insistent; equally striking was the assumption that so many people from such diverse origins could do so.

The magnitude of the post-war migration programme required special accommodation for new arrivals, and the government sought to promote acceptance of non-English-speaking migrants with favourable publicity. Happy families are shown here at the Bonegilla Reception Centre in rural Victoria, 1949.

The acceptance of new Australians was also premised on reassuring the host population that they would not swamp the labour market and threaten local living standards. The system of wage determination by industrial tribunals ensured that migrants enjoyed the same wages as other workers and, by emphasising its new commitment to the maintenance of full employment, the Labor government won the support of the unions for this large influx of new ones. Full employment was the centrepiece of Labor’s post-war planning, the indispensable condition of the light on the hill. In the negotiations at Bretton Woods in 1944 that brought the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank as instruments of trade liberalisation for the new economic order, Australia’s most distinctive contribution was the demand that there be a guarantee of full employment.

In its landmark 1945 White Paper on Full Employment the government outlined a Keynesian approach to management of the economy by control of aggregate demand. Fatalist acceptance of market forces yielded to a close and continuous intervention to ensure the national interest was served. For good measure, the government prepared a raft of public works schemes to soak up any labour surplus that might emerge once the pent-up demand from the war was satisfied. The widely anticipated slump did not occur; rather, the post-war boom continued and gathered force, but the Commonwealth did proceed in 1949 with the most ambitious of these schemes: a diversion of the Snowy River into the inland river system with major hydroelectric generation plants and irrigation works. Accompanying full employment was an expanded social security system, in which cash benefits for the unemployed accompanied increased public provision of housing, health and education.

In all this the Chifley government had to juggle with formidable constraints. A shortage of basic materials meant that rationing continued. An aversion to external debt was one of the legacies of the Depression and this, with support for the British currency and trading bloc, meant that foreign exchange was strictly rationed. Even though the government won national elections in 1943 and 1946, it failed in a 1944 referendum to persuade the electorate to extend its wartime powers into peace, and, in a series of decisions the High Court struck down some of its more innovative measures.

As wartime consensus faded, the omnipresent hand of officialdom became irksome. The frank explanation of a federal minister of the penalties he imposed on State authorities that sold public housing indicated a growing line of division: ‘The Commonwealth is concerned to provide adequate and good houses for the workers; it is not concerned with making workers into little capitalists.’ Yet it was the workers who were expected to show the greatest restraint.

The greatest fear of the government as it grappled with shortages at a time of full employment was inflation. Instinctively frugal, Chifley was determined to hold down wages. His delay in allowing the Arbitration Court to consider the unions’ case for a forty-hour week, which was finally conceded in 1948, and his even greater reluctance to allow wage increases imposed a heavy strain on the loyalty of moderate union officials. Communists were prominent in a wave of strikes in the transport, metal and mining industries, but they were by no means alone in their impatience. Chifley nevertheless interpreted a national stoppage by the coalminers in 1949 as a direct communist challenge and responded with confiscation of the union’s assets, imprisonment of its leaders, raids on the offices of the Communist Party, and the introduction of soldiers into the pits. Three months after the defeated miners returned to work as victims of the iron discipline of Labor austerity, the government was defeated at the polls.

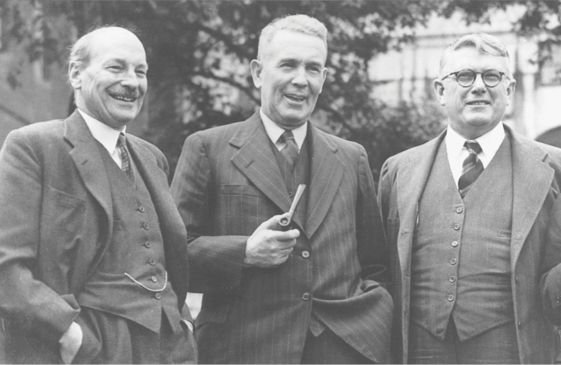

With pipe in hand, Ben Chifley, the Australian prime minister, stands with his British counterpart, Clement Attlee. On his left, the assertive minister for external affairs, H. V. Evatt, is temporarily silent.

The silver age opened with the election of a coalition government of the Liberal and Country parties under the leadership of the revitalised Robert Menzies. His recovery from humiliating rejection in 1941 began with the formation of a new and more broad-based political movement – the Liberal Party – and the construction of a new political constituency that Menzies characterised as ‘the forgotten people’: those salaried and self-employed Australians who identified neither with the company boardrooms nor the tribal solidarity of the manual workers. In extolling the value of his forgotten people, Menzies laid primary emphasis on their ‘stake in the country’ through ‘responsibility for homes – homes material, homes human, homes spiritual’. He solicited the support of wives and mothers whose domestic wellbeing was threatened by the impersonal regimen of bureaucracy and the militant masculinity of striking unionists; yet he also tapped the youthful vigour of the returned servicemen impatient with the regulatory stolidity of Labor politicians still exorcising the ghosts of the Depression.

The new government came to power with an anti-socialist crusade aimed at an electorate weary of controls and shortages. It undertook to reduce taxation and cut red tape. Restrictions on foreign investment were lifted, private enterprise encouraged, wage increases allowed. Yet the continued emphasis on migration and national development ensured the continuation of economic management. During the 1949 election the new Treasurer had singled out Coombs as a meddling socialist; on the day after the poll he phoned Coombs and said: ‘That you, Nugget? You don’t want to take any notice of all that bullshit I was talking during the election. We’ll be needing you, you know.’ As governor of the Commonwealth Bank, which Labor had given the powers of a central bank, Coombs continued to hold the financial levers.

Exporters benefited from the outbreak of war in Korea in 1950, which caused leading industrial countries to stockpile essential commodities. The price of wool increased sevenfold during 1951 to reach record levels, and other primary producers also prospered as new markets emerged. A trade treaty with Japan in 1957 signalled a shift in orientation from Europe to East Asia as the former enemy began to rebuild and industrialise. Domestic industry expanded rapidly with the advantage of tariffs and import quotas. The service sector grew even faster as mechanisation released blue-collar workers to join the white-collar salariat and office blocks rose up over the city streetscape.

An annual growth rate of over 4.2 per cent was maintained in the 1950s and 5.1 per cent in the 1960s. There was full employment, higher productivity, improved earnings, a pattern of sustained improvement that no-one could recall. The chief problem that exercised the economic managers was not insufficient but excessive demand: outbreaks of inflation required credit squeezes in the early 1950s and again in 1960. It was a measure of the new mood that when unemployment rose to 3 per cent, it almost cost the Menzies government the 1961 election.

This was the era in which an economist could characterise Australia as a ‘small, rich, industrial country’, the point at which the ambitions of a settler society to outgrow the confines of dependence reached their zenith. The industrial base broadened as improvements in transport allowed manufacturers to develop a national market and family-owned companies floated on the stock exchange to expand their scale of operations. When he opened a new stage of the Snowy Mountains project in 1958, Robert Menzies declared that ‘this scheme is teaching us and everybody in Australia to think in a big way, to be thankful for big things, to be proud of big enterprises’. A committee of inquiry took economic success as the essential dynamic of national life: ‘growth endows the community with a sense of vigour and social purpose’.

For all its homage to private enterprise, the Menzies government was firmly committed to a strong public sector. The prime minister, who had made his name at the bar in a constitutional case over the powers of the Commonwealth, augmented the national government. When he took up residence in the prime minister’s lodge, Canberra had a population of only 20,000: it was the smallest capital city in the world. A number of his ministers still based themselves in their electorates, visitors to their departments. Although the parliament had shifted from Melbourne a quarter-century before, there were more Commonwealth public servants in the southern city during the mid-1950s than in the national capital. The urbane Menzies embarked on a programme to consolidate administration in Canberra. He, more than anyone else, turned the Australian Capital Territory into a genuine seat of government. By 1965, when the first traffic lights were introduced, it had a population of 100,000.

The augmentation of the Commonwealth increased the rivalry of the States, which competed for investment in the new industries. Tom Playford, who held office in South Australia from 1938–65 with the assistance of a notorious gerrymander, built up steel and motor vehicle production in his State by offering cheap land, infrastructure, and utilities along with quiescent unions. Henry Bolte achieved a similar supremacy in Victoria from 1955–72, and used similar methods to consolidate the manufacturing sector in his State. Among the fruits of his trips to overseas boardrooms was a large petro-chemical complex on the shores of Port Phillip. Others were built at Kwinana, south of Perth, and at Botany Bay, on the southern outskirts of Sydney; in 1971 the novelist David Ireland would make the last of these the site for his dark novel of economic servitude, The Unknown Industrial Prisoner.

That was not how such projects were seen in the 1950s, but they did mark a new phase of development, away from public borrowing and public works to direct foreign investment in business ventures. The new mode of development was more capital-intensive, less concerned with job creation than with profitable enterprise, and it was orchestrated by Liberal rather than Labor premiers. Playford and Bolte were farmers and they exhibited an earthy parochialism as they did their deals and brushed aside critics. ‘They can strike till they’re black in the face’, was Bolte’s response to one group of recalcitrant public employees. Both men joined an insistent cult of development to moral conservatism: strict censorship, six o’clock closing of hotels, and capital punishment were among their hallmarks. Both blamed Canberra for their parsimony.

Each year the revenue of the Commonwealth increased and each year it made grants to the States, which retained primary responsibility for health, education, public transport and other services, though the federal support was never enough to satisfy the rising demand. In its own expenditure the Menzies government encouraged citizens to help themselves. There was assistance to homebuyers, a tax rebate for dependent spouses, subsidies for private medical insurance. Old-age pensions were maintained, other forms of social welfare neglected. The maxim of the silver age was individual initiative.

***

The transition from the iron to the silver age occurred under the shadow of the Cold War. An intense bipolar contest between communism and capitalism dominated world politics from the late 1940s and forced Australia to bind itself more tightly to the Western alliance. The inability of the Labor government to resist the demands of the international Cold War contributed to its fall in 1949 and kept it out of office over the next two decades. At home the Cold War gripped the country and divided the labour movement. A fear of communism permeated almost every aspect of public life, at once impelling the government to improve the welfare of citizens and inhibiting the opportunities for dissent.

At the end of the Second World War the Labor government was both grateful to the United States for leadership of the war in the Pacific and wary of its plans for the post-war settlement. Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill had already allocated the territorial spoils, and the United States was proceeding with plans that would give it unrestricted economic access to the non-communist sphere. Liberal internationalism through the United Nations seemed the best chance for lesser countries such as Australia to safeguard their interests. Revival of the British Commonwealth as an economic and military alliance provided the best chance of a counterweight to American dominance.

Britain was clinging to the white Commonwealth as it struggled to maintain its status as a world power. The loss of India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Burma, intractable conflict in Palestine, and a communist uprising in Malaya brought home the need to reduce the imperial role. After communists won power in China and Indonesian nationalists overthrew Dutch rule in 1949, the independence movement in East Asia was irresistible. In Africa the same impulses forced a less speedy, more contested decolonisation, while the island peoples in what the British high commissioner described as the ‘peaceful backwater’ of the Pacific proceeded subsequently along the same path to self-government.

Other European countries either accepted the loss of their colonies or fought costly rearguard actions to delay the inevitable transfer of sovereignty. Formal empires based on direct rule and displayed in colour-coded maps of the world gave way to an informal imperialism based on trade and investment, aid and armaments, these devices creating shifting spheres of influence and a far less stable world order. Under Labor, Australia accepted claims in the region for national independence (and assisted the formation of the Indonesian republic) while holding fast to its own colonial regime in Papua New Guinea.

The mercurial minister for external affairs, H. V. Evatt, made this a period of intense busyness in Australian foreign policy. In both international forums and direct dealings with Britain and the United States, Evatt sought to play a prominent role, capped by his election as president of the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948. So it was that as luxury cars drew up at the entrance of a palace in Paris to disgorge pinstriped and homburg-hatted diplomats for the opening ceremony, a late-model Ford appeared with ‘a tousle-headed man in a baggy suit, tie askew, sitting beside the driver’. A gendarme instructed to admit dignitaries only who barred his entry was flabbergasted to learn the man he delayed was the new president. On the other hand, a translator at the Conference remembered him years later because he was so rude.

What role could a remote and thinly populated outpost of the white diaspora play? The Americans had no intention of altering their global strategy to accommodate this abrasive representative of a socialist government; they would not share military technology and in 1948 suspended Australia’s access to intelligence information. The British Labour government was also relegated to second-rank status by the United States, and Australia provided important support for its residual economic and strategic interests in the region. The two countries thus embarked on a plan to develop their own atomic weapons with test sites in Australia. It was this project that brought the Cold War security regimen to Australia as British intelligence supervised the formation of the Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation in early 1949 to safeguard defence secrets.

Labor had sought to avert such harsh dictates of the Cold War. While opposed to communist expansion, it could see that the polarisation of world politics into two armed camps would subordinate it to American foreign policy and impose an extreme anti-communism inimical to its own foreign and domestic aspirations. By 1949, however, the Cold War divisions had hardened. Stalinist regimes were installed in Eastern Europe, Germany was divided and the American airlift to Berlin to break a Soviet blockade signalled the heightened confrontation across the Iron Curtain.

The Liberals won office at the end of the year on a platform of resolute anti-communism; it was implemented with military assistance to help Britain defeat the communist insurgency in Malaya, and the dispatch of troops to Korea in 1950 when fighting broke out there between communists and American-led forces. The new minister for external relations discerned a global pattern of communist aggression, now projected south from China to threaten the entire South-East Asian region. In 1951 Robert Menzies warned against the ‘imminent danger of war’.

‘With our vast territory and our small population’, he added later, ‘we cannot survive a surging Communist challenge from abroad except by the cooperation of powerful friends’. The first and indisputably the most powerful of those friends was the United States, and this friendship was formalised in 1951 with the negotiation of a security treaty between Australia, New Zealand and the United States (commonly abbreviated to ANZUS). For the Australian government this treaty cemented a special relationship with its protector, but there were many claimants to such a status and in truth the agreement obliged the United States to provide only as much assistance to Australia against an external aggressor as it judged expedient. ANZUS was essentially a corollary to its system of alliances in the Asia–Pacific region, and served to reconcile Australia to America’s far more important relationship with the former enemy, Japan. Australia was also included in the South-East Asian Treaty Organisation (SEATO), arranged by the United States in 1954 after communist forces defeated France in Vietnam, but that too guaranteed no more than Washington determined.

Britain was a member of SEATO and Australia continued to encourage Britain’s development of nuclear weapons and assist its military presence in Malaya. This was a special relationship of a different kind and in 1956, when Britain defied the United States to join with France in war on Egypt over the administration of the Suez Canal, Menzies unhesitatingly threw his efforts behind the mother country. On returning to office he had announced that ‘the British Empire must remain our chief international occupation’ and he now derided the troublesome ‘Gyppos’ as ‘a dangerous lot of backward adolescents, mouthing the slogans of democracy, full of self-importance and basic ignorance’. He was never reconciled to Britain’s reduced dominion.

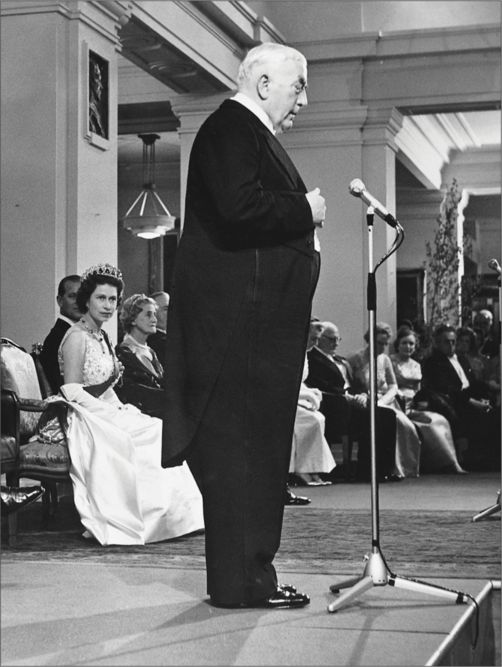

A romantic monarchist and fervent admirer of an idealised ancestral homeland, Menzies in his own words was ‘British to his bootstraps’. His gallantry during the Royal Tour of 1954 was attuned to the immense popularity of the young Queen Elizabeth, the first reigning monarch to visit Australia, but his hyperbole during her subsequent visit a decade later, when he recited the verse of a seventeenth-century court composer, ‘I did but see her passing by / And yet I love her till I die’, made listeners squirm and the Queen blush. His final gesture on the eve of retirement, a suggestion that the country’s new unit of decimal currency should be named the ‘royal’, was mocked into oblivion.

At a state reception in Parliament House, Canberra, on 18 February 1963, Robert Menzies pays fulsome tribute to Queen Elizabeth.

If the delayed but inevitable withdrawal of the British military presence was regretted, the reluctant but equally inescapable turn by Britain away from its Commonwealth trading relationships in order to enter Europe dealt a much heavier blow. It left Menzies’ regular trips to London for Commonwealth meetings and Test cricket as a nostalgic anachronism. His discomfort with the multiracial composition of the Commonwealth, as former colonies became new members, and his defence of the apartheid regime in South Africa made Australia seem another outpost of an obsolete white man’s club.

While Menzies’ foreign ministers displayed greater interest in Asia, they regarded it always through the distorting prism of the Cold War. Even the Colombo Plan, a scheme for co-operative economic development among the Commonwealth countries of South and South-East Asia that brought 10,000 Asian students to study in Australia, was justified as a prophylactic against communist infection. It also brought the beneficiaries into direct experience of a still obdurately White Australia. Australians were present in Asia as advisers, technicians, teachers, diplomats and journalists, but most of all as soldiers. They engaged with their neighbours through travel, study, art and literature, yet Asia remained a zone of contest and danger that required the presence in force of their powerful friends. That need in turn required the Australian government during the 1950s and 1960s to play up the communist danger, to reduce the complexities of history, culture and nationality to the Cold War choice: are you ours or theirs?

It also meant that Australia had to follow the United States even when it was ahead. Fearful of the communist threat from the north, the Australian government exerted all of its limited influence to interpose American forces between China and the South-East Asian countries. From 1962 it provided military instructors to assist the anti-communist government of South Vietnam prevent unification with the communist north. Even before this country became directly involved in Indochina, it reintroduced military conscription, and as soon as President Johnson made the fateful decision to introduce ground troops, in 1965, Australia responded immediately to the request for assistance it had solicited. South Vietnam itself played little part in the decision; it was regarded by the minister for external affairs simply as ‘our present frontier’. Harold Holt, who succeeded Menzies as prime minister in 1966, told his host at the White House that Australia would ‘go all the way with LBJ’. By then, all the way fell some distance short of American expectations: in late 1968, when the American force had grown to 500,000, Australia contributed just 8000. As before with Britain, so now with the United States – obeisance to a powerful protector was payment in kind for defence on the cheap.

A preoccupation with the communist threat from without was linked always to the danger within. During the 1949 election campaign Menzies had undertaken to ban the Australian Communist Party. It was not a legitimate political movement, he insisted, but an ‘alien and destructive pest’ that threatened civilised government and national security. Once elected, he proceeded with the passage of the Communist Party Dissolution Bill, which was enacted in 1950 but immediately challenged by the Communist Party itself as well as ten trade unions. Evatt, the deputy leader of the federal Labor Party and a former High Court judge, appeared before the court on behalf of the Waterside Workers Federation. He persuaded all but one of the current judges that the legislation, which relied upon the Commonwealth’s defence powers, was unconstitutional since the country was not at war.

Menzies persisted with an attempt to obtain the constitutional power by referendum. Evatt, who became leader of the Labor Party following the death of Chifley in mid-1951, carried his party into opposing the proposal. The campaign was intense and the outcome close. While the government failed narrowly to obtain the necessary majority of votes and a majority of States, if just 30,000 voters in South Australia or Victoria had voted Yes rather than No, the proposal would have succeeded. Public opinion polls both before and after the referendum showed a clear majority favoured banning the Communist Party – and it has been suggested that it was the proposal to reverse the onus of proof that defeated the referendum. Even so, it is difficult to imagine that a similar plebiscite in the United States, Britain or elsewhere would have failed to produce a majority in favour of suppressing communism. The affirmation of a basic freedom, the presumption of innocence, even for adherents to a small and vilified cause in the fevered atmosphere of the early 1950s did the country credit.

This was Evatt’s finest hour. He was in no sense a communist sympathiser but alarmed by the sweeping powers the government proposed to employ. Its legislation would have allowed citizens to be declared as communists; upon such a declaration the person named could be dismissed from the public service and disqualified from trade union office; failure to cease activity in a banned organisation would be a crime punishable by up to five years imprisonment. That in proposing these provisions Menzies had falsely identified some trade union officials as communists, and even warned a Labor critic that he might be caught up in their operation, seemed to Evatt and others to threaten essential liberties. The Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation had increased its surveillance over a wide range of non-communists – scientists, academics and writers – and was at this time preparing for the internment of 7000 of them should war be declared. For Evatt to forestall the implementation of this repressive plan was a considerable achievement.

His referendum victory brought him no further success. There was a substantial and growing anti-communist element within the labour movement that condemned Evatt’s appearance before the High Court and was angered by his decision to fight the referendum. It had its origins in a lay religious organisation, the Catholic Social Studies Movement, led by a masterful zealot, B. A. Santamaria, who conducted his crusade against atheistic materialism with the assistance of powerful members of the church’s hierarchy. Through its leadership of Industrial Groups, the Movement had weakened communist influence in trade unions. Since the unions were affiliated to the Labor Party, the Groupers began to capture leading positions in that organisation also. ‘Mad buggers’, Chifley called them shortly before he died, when they defied him to welcome Menzies’ anti-communist measures.

Evatt lost the 1951 election called by Menzies to capitalise on the division in the Labor ranks over the banning of the Communist Party, and the following election in 1954, which was dominated by allegations of communist espionage. The second defeat enraged Evatt, who denounced the Movement and prevailed on the federal executive of the party to replace the hostile leadership of the Victorian branch. A federal conference of the party in 1955 narrowly affirmed the executive’s action. The dissidents broke away to form their own Anti-Communist Labor Party, later renamed the Democratic Labor Party, and they brought down Labor governments in Victoria and Queensland.

Through the preferential system of voting, which allowed those who followed the Democratic Labor Party to direct their support to the coalition, this split ensured conservative dominance in national politics for more than a decade. At the end of the war there were Labor governments in the Commonwealth and five of the six States, but by 1960 just New South Wales and Tasmania, where Labor moderates cared more for power than ideological purity, remained in the party’s hands. The split divided workmates and neighbours, poisoned the labour movement, and left a Labor leadership clinging to past glories with policies that were increasingly remote from the interests and sympathies of younger voters. As affluence and education eroded its manual working-class base, one commentator wondered if it was not doomed to Labor in Vain?

The very failure of Menzies to carry his referendum proposal to ban the Communist Party enabled him to take maximum advantage of the red scare. On the eve of the 1954 election the prime minister announced the defection of a Soviet diplomat, Vladimir Petrov. His wife, Evdokia, was rescued at the Darwin airport from two thugs escorting her back to Moscow. Petrov claimed to have gathered information from a communist spy ring in Australia that included diplomats, journalists, academics and even members of the staff of the leader of the Labor Party. The government established a royal commission to investigate these allegations, before which Evatt appeared until his intemperate response to its partial conduct led to his being barred from the hearings. In the Cold War atmosphere of the 1950s, the Petrov inquiry strengthened Menzies’ claim that the Labor Party was contaminated by communism, its leader’s ‘guise of defending justice and civil liberties’ merely a cloak for shielding traitors.

Soviet officials escort Evdokia Petrova, the wife of a Russian diplomat, onto an aircraft at Sydney after her husband asked for political asylum. Petrova was released from their custody and taken off the flight at Darwin.

The royal commission found no evidence that would justify the laying of charges against any Australian, but it blackened the names of many Australians who were denied any right of reply, their careers blighted, their children bullied at school. The Communist Party itself was a declining force, the revelations made in 1956 by Khrushchev about the Stalinist terror and then the Soviet repression of Hungarian liberalisation destroying its credibility and reducing the membership to fewer than 6000. Nevertheless, the domestic Cold War continued to excoriate dissent. Apart from the Petrov inquiry and an earlier State royal commission into communism, the domestic Cold War did not produce any Australian equivalent to the American system of loyalty oaths, Congressional inquisitions and systematic purges. Rather, it operated at two levels, the clandestine surveillance of the Australian Security and Intelligence Organisation and the mobilisation of public opinion to secure acceptance of security measures.

The process was advanced in a campaign launched on the national radio network two months after the defeat of the referendum to ban communism. Advised of an announcement of the gravest national importance, listeners heard the chairman of the Australian Broadcasting Commission deliver the warning that ‘Australia is in danger … We are in danger from moral and intellectual apathy, from the mortal enemies of mankind which sap the will and darken the understanding and breed evil dissensions.’ This ‘Call to Australia’ was encouraged by Menzies, headed by the chief justice of the Victorian supreme court, endorsed by all but one of his interstate counterparts and the leaders of the four principal churches, financed by business magnates, and organised by a Movement associate of Santamaria.

It set the tone for much of the subsequent campaign with its language of chiliasm. In an unusual departure from his usual separation of church and state, Menzies talked of the Cold War as a battle between ‘Christ and Anti-Christ’. Tactical Cold War initiatives included the creation of the Australian arm of the American-sponsored Congress for Cultural Freedom to fight the war against communism among the intellectuals. The editor of its magazine, Quadrant, was James McAuley, a poet converted from anarchism to Catholicism of so conservative a temper that he railed against the liberal humanism his organisation was ostensibly defending.

The Cold War was prosecuted in the government’s scientific organisation, the universities, literary associations and almost every corner of civic life. The mother of a well-known communist was expelled from her local branch of the Country Women’s Association for refusing its loyalty oath; since she could no longer play the piano at its meetings, the members had to endure an inferior rendering of ‘God Save the Queen’. Not even sport escaped. During the 1952 season of the Australian Rules football competition in Victoria, ministers gave half-time addresses on the Call for Australia. A prominent Methodist preacher found the audience at the Lakeside Oval in South Melbourne unreceptive and appealed to common ground with the claim that ‘After all, we are all Christians.’ ‘What about the bloody umpire?’ came a reply from the outer.

***

The communist threat operated as a powerful inducement for capitalist democracies to inoculate their peoples with generous doses of improvement. The rivalry between the Eastern and Western blocs was conducted both as an arms race and a competition for economic growth and living standards. Freedom from hardship and insecurity would deprive the agitator of his audience; regular earnings, increased social provision and improved opportunity would attach beneficiaries to their civic duties. But improvement brought its own dangers. In the Call to Australia there was a concern that a prosperous mass society was vulnerable to a loss of vigour and purpose; hence its admonition against moral and intellectual apathy. As early as 1951 Menzies warned that ‘If material prosperity is to induce in us greed or laziness, then we will lose our prosperity.’ Between 1945 and 1965 average weekly earnings increased by more than 50 per cent, and the five-day working week became the norm along with three weeks of paid annual leave. The transformation of social life this prosperity effected was accompanied by a cluster of moral anxieties.

In the course of the long boom the mainland cities spread rapidly beyond their earlier limits. The population of Sydney passed 2 million in the late 1950s, Melbourne in the early 1960s, while Adelaide and Brisbane were approaching 1 million and Perth had grown to more than half a million. The city centres were rebuilt in concrete and glass to provide for their expanded administrative and commercial activities, but the most significant movement was out of the inner suburbs to new ones on the peripheries. At the end of the war an acute housing shortage forced families to share dilapidated terraces. By the beginning of the 1960s a modern, detached home on a quarter-acre block had become the norm. While some of the new housing was publicly constructed, most of it was built by private developers or the occupiers themselves. The first object of most married couples was to purchase a lot, then save till they could build. A 1957 ‘portrait of a new community’ on the outskirts of Sydney described ‘nights and weekends … alive with the constant beat of the hammer, the whirr of the saw, the odorous skid of the plane’. After this initial occupation came the erection of fences, the making of gardens and the weekend whine of the motor mower; then the working-bee on the school playground and the church hall.

Religious participation increased during the 1950s to a high point of 51 per cent of women and 39 per cent of men by the end of decade. The growth was particularly marked in the new suburbs, where the church provided a range of community activities for young families: Sunday schools, youth clubs, choirs, discussion groups, tennis, football and cricket. It was an era of religious zeal sustained by missions, campaigns and crusades to claim converts and heighten commitment. An Irish-American priest brought the World Family Rosary Crusade to Australia in 1953 with his slogan ‘The family that prays together stays together’, and drew huge rallies. The American evangelist Billy Graham attracted record crowds during his Crusade in 1959. Christianity flourished as a protector of family life and moral guardian of youth.

The rate of home ownership increased from 53 per cent in 1947, which was the historic norm, to an unprecedented 70 per cent by 1961, among the highest in the world. Along with the residences went the factories. The older workshops and warehouses that threaded the inner-city streets were abandoned for new purpose-built plants further out. The sound of the hooter, the bustle of movement, the discharge of waste and the din of industry yielded to the hum of the generator and the orderly motion of the assembly line on free-standing industrial estates.

Joining home to work was the motor car. In the early 1950s one Australian household in three owned a car; by the 1960s, two in three. Cars and trucks freed industry from the constraints of location on rail-lines. They enabled the cities to sprawl, filled the wedges of country between the radial transport routes with commuter suburbs. Public transport languished, trams were removed to make way for the rush-hour stream of motor traffic, and by the 1960s freeways were slicing through inner suburbs. Cars created new forms of leisure, such as the drive-in theatre; new ways of holidaying with the caravan or motel replacing the guest-house; new forms of shopping at suburban supermarkets; new rituals such as the Sunday drive, customs in common but now performed with greater privacy. Even courtship was mobilised as young men borrowed the family car on a Saturday night. In 1950 the majority of engaged couples in the city of Melbourne lived in the same or adjoining suburb, but by 1970 most came from suburbs well beyond walking or cycling distance. A 1956 advertisement for General Motors-Holden exploited the new possibilities:

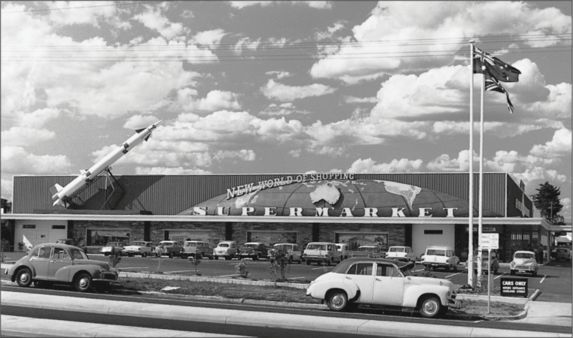

The move to the suburbs and the accumulation of possessions within the suburban home redefined the role of the housewife. Her contribution as a domestic provider was shrinking, her role as a consumer growing. She shopped less frequently now that she had a refrigerator, and home deliveries of ice, bread, meat, vegetables and groceries from local traders were giving way to shopping by car at ‘cash-and-carry stores’, and soon the supermarket.

The convenience and abundance of the supermarket proclaimed the triumph of modernity. This early example combines the technology of the space age with national and imperial flags.

Visitors to Australia were struck by the segregation of the sexes; local experts took it as an amenity of the growing affluence. ‘Whenever they can, Australian women mostly revert to their favoured roles of full-time wives and mothers’, one wrote in 1957. Whether through choice or need, an increasing proportion did not. Between 1947 and 1961 the number of married women in the workforce increased fourfold, and in 1950 the Arbitration Court increased women’s pay to 75 per cent of the male basic wage. Yet women’s employment remained subsidiary to their responsibilities in the home. The new commuter suburbs on the edges of the cities were places where men commuted and women stayed.

The cities themselves became far more conscious of their images. When Melbourne won the right to stage the 1956 Olympic Games, its image-makers worried that the licensing restrictions, the lackadaisical taxi drivers and even the bare linoleum on hotel floors might hold it up to international ridicule. Friendliness became the motif, the dominant theme a mix of graceful parks and gardens with ‘rising tiers and spreading flats of steel and concrete, bronze and glass, in great buildings, modern in conception, at once functional and imaginative in execution’. The year 1956 also brought television, a potent medium to extend familiarity with the plenitude of idealised American family shows and to enlist viewers of the commercial channels in the drama of consumer desire. Advertising became a major business, divining and shaping those desires.

The first television consoles took pride of place in the family living room. Along with the advertising industry, programmers distinguished the male breadwinner from the housewife and the children but took longer to disaggregate its audience into markets with distinct styles and tastes. The post-war family was widely regarded as the basic unit of society, undifferentiated in structure and function if not in circumstance. It was a ‘nuclear family’, that term denoting the absence of additional members in the self-sufficient suburban setting, but also suggesting that this arrangement animated social life. The post-war demographic bulge, with marriages deferred until after the war and then several children coming in rapid succession, encouraged the belief. A higher marriage rate at younger ages increased the birthrate. The ‘baby-boomers’ swamped the maternity hospitals and infant welfare centres after the war, then during the 1950s burst the capacity of primary schools. By the 1960s they forced a crash programme to build and staff secondary schools for the increasing numbers that stayed on beyond the school-leaving age and even continued to university.

The Commonwealth government welcomed the trend as an investment in social capital and an enhancement of national capacity. A nuclear research laboratory was the first major building to go up at the post-war Australian National University, its school of physics the most ambitious and expensive section of the institute of advanced studies. After Menzies initiated a review in 1956 that led to Commonwealth funding of universities, a nuclear physicist conducted a second major inquiry in 1961–64 that guided the expansion of higher education. The boost to science education following the success of the Soviet Sputnik led in 1963 to the first government support of private schools with Commonwealth provision of their science laboratories. Never before had the custodians of scientific knowledge commanded such authority or flaunted it so confidently. The chairman of the country’s Atomic Energy Commission explained that ‘technological civilisation’ presented a stream of complex problems that ‘only a small proportion of the population is capable of understanding’. To submit such issues to the voter or the politician could ‘only lead to trouble and possible disaster’: ‘the experts must in the end be trusted’.

Yet the nuclear family was beset by dangers. It was menaced by sexual irregularity, the repression of homosexuality gathering force from its Cold War associations with disloyalty. It was vulnerable to breakdown, the sharp increase in divorce after the war of intense concern to churches that, despite their revival, seemed to be losing their moral authority to materialism and secularism. It was preoccupied with youth, the discovery by psychologists of the adolescent and the cultivation by consumer industries of the teenager helping to mark out a disturbing additional figure: the juvenile delinquent.

Two contrary tendencies operated here. On the one hand, young people were readily able to find work, had greater disposable income and were presented with an array of products – clothes, records, concerts, comics, dances, cinema, even motorbikes and cars – on which to spend it. On the other, the demands of suburban domesticity and the extended dependence associated with further education enclosed teenagers within heightened expectations. The moral panic generated by the ‘bodgie’ and ‘widgie’ in the rock-and-roll era of the 1950s, and variant identities associated with later musical styles, each with its distinctive dress, dialect and ritual, was also a class phenomenon. The teenager from a working-class home was least likely to defer entry to the workforce, most likely to become the ‘social misfit’ who resisted the suburban dream.

At the same time as conservatives denounced this juvenile delinquent, however, radicals lamented the disappearance of the working-class rebel. Cold War inroads into the trade unions, coupled with new powers of the Menzies government to penalise strikes, reduced industrial conflict. The decline of the older occupational neighbourhoods, with their dense overlay of work and leisure, family and friendship, seemed to such critics to weaken class solidarity. They saw the increased social and geographical mobility, the new patterns of consumption and recreation, as attaching suburban Australians to the pleasures of the home and family at the expense of work-based loyalties.

As before when confronted with the failure of millennial expectations, the left retreated into a nostalgic idealisation of national traditions. Its writers, artists and historians turned from the stultifying conformity of the suburban wilderness to the memories of an older Australia that was less affluent and more generous, less gullible and more vigilant of its liberties, less conformist and more independent. In works such as The Australian Tradition (1958), The Australian Legend (1958) and The Legend of the Nineties (1954) the radical nationalists reworked the past (passing over the militarism and xenophobia in the national experience) to assist them in their present struggles. Try as they might to revive these traditions, the elegiac note was clear. The radical nationalists codified the legend of democratic and defiant mateship just as modernising forces of change were erasing the circumstances that had given rise to that legend.

As the radical romance faded, the conservative courtship of national sentiment prospered. It was embedded in government policies designed to assimilate a population of increasing ethnic diversity into the customs and values of their adopted country. In the two decades after 1947 more than 2 million migrants settled here, the majority from non-English-speaking countries. With their children they contributed more than half the population increase to more than 12 million by the end of the 1960s. ‘Our aim’, Arthur Calwell had laid down in 1949, ‘is to Australianise all our migrants … in as short a time as possible’. Although his Liberal successors relaxed the opposition to foreign-language newspapers and ethnic organisations, that aim continued. ‘We can only achieve our goal through migration’, the new minister declared, ‘if our newcomers quickly become Australian in outlook and way of life’. On the ships, in the holding centres and migrant hostels, in English-language classes and naturalisation ceremonies, through ‘Good Neighbour’ committees and other voluntary bodies, they were taught the Australian Way of Life.

That term allowed a shift from the restrictions of ancestry or the traditions of national legend to the cultivation of life-style. Its depiction of Australia as a sophisticated, urban, industrialised consumer society had clear Cold War implications. An article on ‘The Australian Way of Life’ written by a refugee for the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Commonwealth spelt them out: ‘What the Australian cherishes most is a home of his own, a garden where he can potter and a motor car … A person who owns a house, a garden, a car and has a fair job is rarely an extremist or a revolutionary.’

The gap between expectation and reality was there from the beginning. On New Year’s Day 1947 two Commonwealth ministers welcomed the first party of post-war British migrants. There were 200 of them, ex-servicemen with trade skills who were to work on building projects in Canberra. Yet within a week they were complaining about living conditions in the barracks in which they were quartered. ‘There has been a little too much pandering to these fellows’, insisted the minister for works who claimed he had put up with poorer conditions and was adamant ‘we are certainly not going to wet nurse them’. A special effort was made to attract British settlers and over 600,000 were assisted to come to Australia over the next two decades, but complaints persisted. The term ‘whingeing pom’ entered contemporary usage in the early 1960s. It might well have been that British migrants were more ready to express dissatisfaction than their non-English-speaking counterparts; but it also indicated that the Australian way of life was becoming less British.

More modest expectations governed Aboriginal policy. In 1951 the Commonwealth minister for territories confirmed the official objective of assimilation: ‘Assimilation means, in practical terms, that, in the course of time, it is expected that all persons of Aboriginal blood or mixed-blood in Australia will live like white Australians do.’ That would require ‘many years of slow, patient endeavour’ and ‘to be accepted as a full member of Australian society, he has to cease to be a primitive Aboriginal’. The States began to close down their reserves, pushing them into country towns where they experienced pervasive discrimination. Migrant Australians responded to broken promises with protest but their ultimate recourse was to return home. Indigenous Australians had no such opportunity, though they too sought their homelands.

Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Pilbara region of Western Australia went on strike for better pay in 1946 and, despite official harassment, they secured improvements; but not all of them returned to work, for they had established their own co-operative settlement. Again in 1966, 200 Gurindji walked off a pastoral station in Central Australia and a claim for equal pay turned into a demand for their own land. Between these two most celebrated actions were numerous lesser ones, fiercely resisted by pastoralists and governments and commonly blamed on communist agitators. There were communists involved on both occasions, and communist-led unions were most active in their support. In Darwin the communist officials of the North Australian Workers Union backed post-war Aboriginal claims for equal pay, while their successors abandoned the campaign. The Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines, formed in 1957 by the left, assisted a new generation of Aboriginal activists.

There was growing unrest on the reserves. Palm Island, an Aboriginal settlement off the coast of Queensland used for the confinement of recalcitrants on similar lines to the convict settlements more than a century earlier, saw an uprising against a tyrannical superintendent in 1957. The victimisation of the Aboriginal artist Albert Namatjira, denied permission to build a house in Alice Springs a year after he was presented to Queen Elizabeth, and gaoled for six months in 1958 for supplying alcohol to a relative who was not a citizen, drew attention to the absence of assimilation.

That policy was proclaimed in government publications showing Aboriginal children in the classroom, the boys in shorts and white socks, the girls in cotton tunics, novitiates to the Australian way of life. It was practised in the removal of children from their families so that they could better be trained in ‘white ways’, an activity that continued through the 1950s and into the 1960s. Not until the early 1980s was there a belated recognition by government of the trauma of separation with the establishment of the first Link-Up agencies.

The casualties of the Australian way of life were seldom acknowledged in the celebration of post-war achievement. It was a golden age of sport, with Australian triumphs on the cricket field against England after the war heralding an era of success in athletics, swimming, tennis and golf. The ‘golden girls’ dominated the track at the Melbourne Olympics, when Australia won thirty-five medals, and both men and women continued their supremacy in the pool. In the post-war decades Australian men won half the major tennis titles and achieved fifteen Davis Cup victories in twenty years. These keenly followed contests with the United States became a surrogate for the relationship between the two countries, mediating dependence as Test cricket had done for the imperial relationship.

Australians liked to think that their egalitarian ethos, favourable climate and broad participation (there were more tennis courts in relation to population than any other country in the 1950s) prevailed over the grim professionalism of the Yanks. In truth, tennis in America was restricted to the wealthy amateur, whereas the Australians bent the rules with sponsorship, coaching and other forms of ‘shamateur’ assistance. It was an American professional who remarked that the Australians had ‘short arms and deep pockets’.

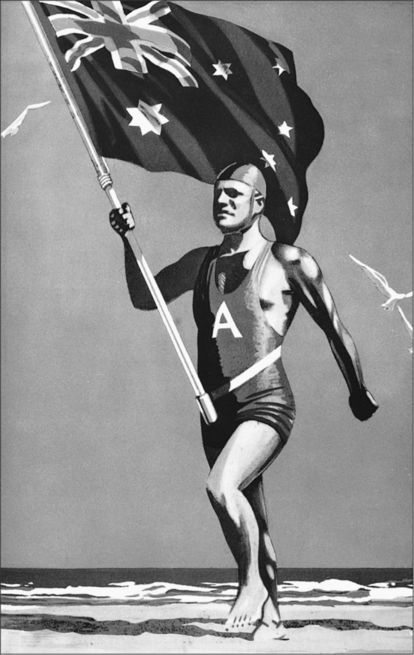

The amateur ideal was expressed better at the beach, where surf lifesaving clubs patrolled the breakers to rescue over-adventurous swimmers from the treacherous rip. With their combination of voluntarism, masculinity (women were initially excluded) and competition, the lifesaving clubs blended the hedonism of the beach with the militarised discipline of belt drill and march past. As one club historian put it, they were ‘truly Australian in spirit’, their free association in ‘humanitarian mateship’ without barriers of creed, class or colour an example of democracy ‘as it was meant to be’.

The golden age lasted through the 1960s until the early 1970s, but before then Australia was caught up in mounting problems. The retirement of Robert Menzies at the beginning of 1966 might be taken as a turning-point in the government’s fortunes. The last prime minister to choose his moment of departure, he was at the age of seventy-one a man out of sympathy with the times. At a recent meeting of Commonwealth prime ministers in London he had been ‘sad and depressed’, for ‘people like me are too deeply royalist at heart to live comfortably in a nest of republics’. His minister for immigration wanted to ease the White Australia policy on the grounds that its restrictions were discriminatory, but Menzies was adamant: ‘Good thing too – right sort of discrimination’. His departure released the brake on these aspects of national policy so that in 1966 Australia signed the international convention on the elimination of racial discrimination, and in the same year began to admit larger numbers of non-European immigrants. The discriminatory provisions against Aborigines in the Commonwealth Constitution were repealed in 1967.

Surf life-saving clubs patrolled Australian beaches to rescue swimmers from being swept out to sea. A formal march was a feature of their competitive carnivals. Here a stylised flag-bearer leads the way.

Yet so complete was Menzies’ political mastery that the task of succession proved beyond the conservatives. The remaining six years of the ‘Ming dynasty’ saw three prime ministers, Harold Holt, John Gorton and William McMahon, pass in rapid succession. Holt was a genial, easygoing man who drowned while swimming at an unpatrolled beach as discontent mounted – a pillar of the Melbourne establishment remarked later that he was out of his depth. Gorton struck out more boldly with a larrikin style of assertive nationalism that offended traditionalists, and fell to a palace revolt. McMahon was the feeblest and he was routed in a general election that drove the Liberal and Country Party coalition from office. Some of the difficulties the coalition faced were beyond its control, some of its own making; such were the expectations after two decades of rule that it was blamed for most of them.

The Vietnam War proved the heaviest millstone round the conservatives’ neck. At first it was popular and used by them to renew the coalition’s electoral mandate in 1966 and 1969. Visits by the American president as well as the leader of South Vietnam boosted the government’s stocks, as much because of as despite the noisy protests these visits occasioned. ‘Ride over them’, the Liberal premier of New South Wales responded when informed that demonstrators were blocking the motorcade of President Johnson in 1966, and then improved on that by telling a United States Chamber of Commerce luncheon that he had instructed a police superintendent to ‘run over the bastards’. But the Tet Offensive of 1968 punctured the illusion of American superiority and drove Johnson out of office. His successor resorted to mass bombing and invasion of Cambodia, then Laos, in a forlorn endeavour to stave off inevitable defeat. Meanwhile the Australian casualties mounted. Of 50,000 who had served in Vietnam by 1972, 500 were killed and they included nearly 200 conscripts.

Conscription for an unjust war was the primary issue for a peace movement that began with the lonely vigils of the women’s group, Save Our Sons, and swelled into noisy protest by radical students until by 1970 it filled city streets with a demonstration, the Moratorium, in numbers not seen for decades Horrifying images of children with napalm burns, television footage of street executions and reports of village massacres combined with the bizarre ritual whereby young Australian men were required to register for national service and then face selection by drawing birthdates from a barrel in a ‘lottery of death’. A generational divide widened between government ministers who sought to justify the war and those they sent to fight it.

By 1970 the government began withdrawing Australian forces and scarcely bothered to pursue the growing numbers of draft resisters.

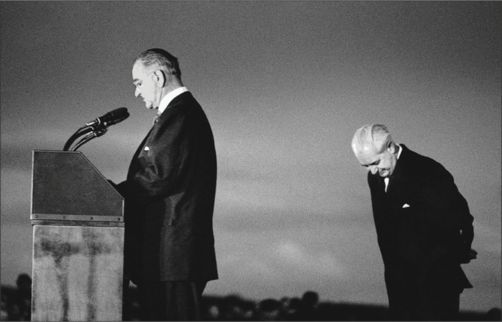

In 1966 the prime minister Harold Holt visited the United States to proclaim that Australia would go ‘all the way’ with its ally in Vietnam. Four months later President Johnson returned the visit. He is shown here speaking at the Canberra airport with Holt in submissive deference.

The war came to an end with the fall of Saigon in 1975, but the Australian involvement ceased in 1972 when it was clear that its strategy of forward defence lay in tatters. President Nixon had signalled the withdrawal of the United States from the Cold War alliance in South-East Asia; his visit to China in 1972, exploiting the breach between that country and the Soviet Union, undermined the insistent logic of Australian foreign policy since 1950, which was built on the assumption of a monolithic communist threat. Australia had eagerly followed its powerful friend into Indochina, only to discover ‘how military decisions are being made for political ends’, as one minister lamented. More than this, he was astonished to discover ‘that public opinion can be mobilised to interfere with public policy’, an intrusion he likened to the actions of the London mob on the eighteenth-century British parliament. An egregious colleague attempted a more modern comparison when he described the Moratorium demonstrators as ‘political bikies who pack-rape democracy’. This was a government badly out of touch.

The Korean War had stimulated the world economy; the Vietnam War overtaxed it. The United States met the huge cost by printing dollars, which as the reserve currency for international trade washed into the financial system and increased inflationary pressures. By the end of the 1960s there were clear signs of strain in the Australian economy. Farmers continued to increase production but faced a steady decline in returns; caught in a cost-price squeeze, they had to form larger holdings. The new technologies were eroding rural life. Small towns that served locals during the horse-and-buggy days dwindled as farmers drove to larger centres; the local telephone exchange no longer employed rural girls once it was automated; the railway station where their brothers worked lost out to the bus stop, and the bush school closed now that the bus could take children to a larger one. By 1971 there was an absolute drop in the rural population to less than 2 million, just 14 per cent of the national total.

It was fortunate that new mining discoveries allowed the sale of bauxite and iron ore to Japan. There had been a ban on the export of iron ore until the discovery of rich reserves in Western Australia enabled the premier to persuade Canberra to lift it in 1960, and soon new mines in Queensland and the Northern Territory increased the production of bauxite. The bulk shipping of base metals contributed a quarter of the country’s exports by the end of the decade and discovery of a major oil field in Bass Strait in 1966 brought Australia closer to self-sufficiency in fossil fuels.

While the mineral boom excited a speculative flurry on the stock exchanges, the national economy remained heavily dependent on foreign capital and imported technology. Large companies dominated major industries, with protection restricting competition, and a high level of foreign ownership in key sectors such as the car industry. Full employment allowed unions to become more aggressive in demands for wage increases. Twenty years of industrialisation and urban growth created new dissatisfactions. The inner suburbs were pocked with decay and pollution. The outer suburbs lacked basic services; many remained unsewered. Provision of health and education lagged behind demand. A pattern of private affluence and public neglect was clear.

The beneficiaries of affluence began to reject their inheritance. As the Australian way of life was established in the new suburbs, its chief critics were intellectuals who used the weapons of irony and parody. In his stringent condemnation of Australia’s Home (1952), the architect Robin Boyd condemned the ‘aesthetic calamity’ of a suburbia that carried bad taste to the ‘blind end of the road’. He inveighed against the ‘wild scramble of outrageous featurism’ that disfigured the wealthier neighbourhoods, just as another architect deprecated the ‘sterile little boxes tinged with an anaemic echo of wrought iron and a carport’ in the mortgage belt. In satirical monologues first developed for a university revue in 1955, the entertainer Barry Humphries, who had grown up in the heart of Melbourne’s middle-class suburbia in a house designed by his father, created a range of characters addicted to mediocrity: the upwardly mobile Edna Everage and her hen-pecked husband, Norm; the invincibly platitudinous Sandy Stone. ‘I always wanted more’, is the opening sentence of Humphries’ memoirs.

He and tertiary-educated contemporaries such as Germaine Greer, Robert Hughes and Clive James would abandon Australia to achieve international success. Unable to reconcile themselves to the dullness, the conformity and the philistinism of their youthful homeland, as ‘expats’ they would remain trapped in the role of gadflies. Other malcontents fled suburbia for the refuge of the inner-city surrounds, where European migrants were beginning to create a more metropolitan ambience with wine, food and street life – only to assist in the gentrification of their sanctuary.

Before that occurred there was a flurry of rebuilding as houses were replaced by flats – not the high-rise monoliths of bleak uniformity erected for public tenants, as their heyday was the 1950s, but smaller constructions of six or eight units that private developers squeezed onto suburban blocks. More than 200,000 were built during the 1960s, mostly in Sydney and Melbourne, either for sale to retirees or rent to young Australians wanting their own self-contained accommodation. Here was a further challenge to the conventional family home as the flat offered independence from parental supervision and ‘flatting’ became shorthand for sexually active young men and women living alone or with friends of either sex. The flat provided a refuge from the norms of heterosexual monogamy at a time when the baby-boomers were experimenting with alternative lifestyles, and the counter-culture was demanding liberation from laws against obscenity, abortion, homosexuality and hallucinogenic substances. In 1967 the editor of Sydney University’s student newspaper, Keith Windschuttle, proclaimed a demonstration in Hyde Park ‘where groovers would turn on in public with LSD’ to defy new State legislation declaring it a drug of addiction.

All three of Menzies’ successors sensed the mood for change but struggled to satisfy it. Harold Holt seized on the International Exhibition at Montreal in 1967 as an opportunity to present Australia as a modern and sophisticated country. Robin Boyd designed a ‘luxurious and civilised’ pavilion, yet it was stocked with kangaroos, wallabies and sheep. The official guide celebrated artists such as Sidney Nolan, writers such as Patrick White (who would win the Nobel prize for literature in 1973) and singers such as Joan Sutherland, yet the entertainers at Montreal featured Rolf Harris singing ‘Tie Me Kangaroo Down, Sport’. Rupert Murdoch’s new national broadsheet, The Australian, lamented that ‘the Aussie flavour of the whole performance was one of dedicated provincialism’.

John Gorton endorsed the establishment in 1968 of an Australian Council for the Arts to nurture creativity, and in 1969 created the Australian Film Development Corporation. Its first feature film was The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, based on a cartoon series in the satirical London weekly, Private Eye. Barry Humphries was its author, and drew on a mixture of schoolboy and service slang, as well as his own imagination, for the dialogue. A New Zealander was the artist and he invented the character of Barry McKenzie as a colonial innocent in post-imperial London, taking his first name from Humphries, his surname from a strong-bodied Australian cricketer, his suit and wide-brimmed hat from middle-aged Anzacs he had seen marching down Whitehall on Remembrance Day, and his jutting chin from the comic-strip character Desperate Dan. The comic strip was censured in Australia but its English readers delighted in Barry McKenzie’s colloquialisms and adopted them as their own, so that they too were soon pointing Percy at the porcelain. Humphries used the film to mock the Australian government’s cultural patronage: he has Bazza visiting an expatriate mate in Paris and telling him: ‘Don’t let this clapped out culture grab you, mate. I mean back in Oz now we’ve got culture up to our arseholes.’

McMahon, the last of the Liberal lineage, was the least comfortable with the forces of change. He inherited the Council for Aboriginal Affairs, established by Holt in the aftermath of the 1967 constitutional referendum to improve the circumstances of Indigenous Australians and chaired by H. C. Coombs, the former governor of the Reserve Bank. McMahon was anxious to capitalise on this prestigious association but found himself caught between the expectations of Aboriginal progress and the intransigence of his ministers who were responsible for its implementation.

Earlier reforms – in 1962 the franchise was extended to Aboriginals, in 1965 the Arbitration Court awarded equal pay to Aboriginal pastoral workers – were designed to remove the formal disadvantages that prevented Aborigines from becoming free and equal citizens of Australia. The constitutional changes introduced in 1967, while commonly regarded as conferring citizenship, singled out Aboriginal Australians as a special category of people for whom the Commonwealth could legislate over the discriminatory arrangements of more conservative States. The Coalition government failed to do so. Rather, it resisted the growing demands of Aborigines for self-determination. Just as the Commonwealth had rejected the land claim of the Gurindji in Central Australia in 1967, so it opposed a court action brought in 1968 by the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land who opposed mining of bauxite on their land. Back in 1963 the Commonwealth parliament had dismissed their bark petition against the excision of this land. Now it condemned the legal claim as ‘frivolous and vexatious’.

These disappointments in areas of traditional occupation were accompanied by an upsurge of Aboriginal protest in the towns and cities of the south. Young activists no longer worked through white organisations for equality; rather, they celebrated their distinctiveness, their ‘black pride’ and their ‘black power’. ‘Black is more than a colour, it is also a state of mind’, said Bobbi Sykes. These ideas drew on overseas precedents. Just as a Freedom Ride by student radicals through rural New South Wales in 1965 echoed a tactic of the civil rights movement in the United States, so the more forceful assertion of a separate identity followed a similar turn there.

The most spectacular display of black power in Australia came after McMahon used an Australia Day speech to reject land rights. Aboriginal protestors responded by occupying the lawns in front of Parliament House in Canberra. Erected on Australia Day, 1972, this tent embassy symbolised the changed objective – no longer acceptance but recognition. For months it remained until a rattled prime minister created a new ordinance to have it removed. Television screens showed the ensuing struggle between the police and its custodians. ‘Everybody knows’, the leader of the Labor Party proclaimed, ‘that if it were not the young and the black involved in this matter the Government would not have dared to proceed’. He was in fact performing the obsequies for a government that was voted out of office a few weeks later.

***

The Labor leader was Gough Whitlam, elected to that position in 1967 after a long struggle with Arthur Calwell, the gnarled centurion of the old guard. Calwell was steeped in Labor tradition, hamstrung by its rules – a newspaper photograph of the parliamentary leader waiting outside a meeting of the federal executive in 1963 allowed the Liberals to claim that Labor was directed by thirty-six ‘faceless men’. Whitlam, a large man of magisterial self-regard, was a moderniser who directed his initial energies into modernising his own party. He sought to discard its socialist shibboleths, the preoccupation with trade union concerns and Cold War recriminations, so that it could attract the suburban middle class. Accordingly, he developed policies designed to make good the failures of twenty years of coalition rule. In modern conditions, he argued, the capacity to exercise citizenship was determined not by an individual’s income ‘but the availability and accessibility of the services which the community alone can provide and ensure’.

Through an enlargement of government activity, he would apply the national wealth to projects of urban renewal, improved education and health, and an expanded range of public amenities. He would sweep away the accretion of restrictions and special interests to augment the nation’s capacity and enlarge the life of its citizens. Whitlam was the first ‘silvertail’ to lead the federal Labor Party (in South Australia another defector from the establishment, Don Dunstan, anticipated his success with similar policies at the State level) and the first to abandon labourism for social democracy. Tellingly, when asked to give an example of how he understood equality, he replied that ‘I want every kid to have a desk, with a lamp, and his own room to study’. The light on the desk replaced the light on the hill.