The first visitors to Hout Bay were sailors on the ship Consent, which anchored just outside the bay in July 1609. The mate, most probably a man named John Chapman, was sent in a pinnace to judge the bay’s suitability as a harbour. The ship’s pilot named the bay Chapman’s Chance, and described it as a ‘very good harboure for ships: for the maine land of the Cape will be shut in upon the wester-side of the land’.

In May 1652, shortly after Jan van Riebeeck’s arrival at the Cape, an expedition discovered a fine forest in the area. This became the main source of timber for the Dutch East India Company. The name Hout Bay first appears in Van Riebeeck’s journal entry for 11 July 1653, when he referred to it as ‘de schone bosschagie … genaemdt de Houtbay’ (the beautiful wooded area named Hout Bay).

The first farmers in the area were Pieter van der Westhuizen and Schalk Willem van der Merwe, who were granted land there in 1677. They were to plant grain, and send 10 per cent of their harvest to the Dutch East India Company. However, trying to wrest a harvest from virgin land was not easy, and the wild animals in the area carried off their cattle. Both farmers gave up the unequal struggle and returned to Table Bay.

Later efforts at farming were more successful, and the farm named Kronendal flourished. When the Kronendal estate was put up for auction in 1832, its extent was about 2 200 morgen (1 880 hectares). The advertisement of the auction in the Cape Argus mentions ‘a large and commodious dwelling house, wine store, stabling, slave apartments, blacksmith’s shop, [and] water mill’.

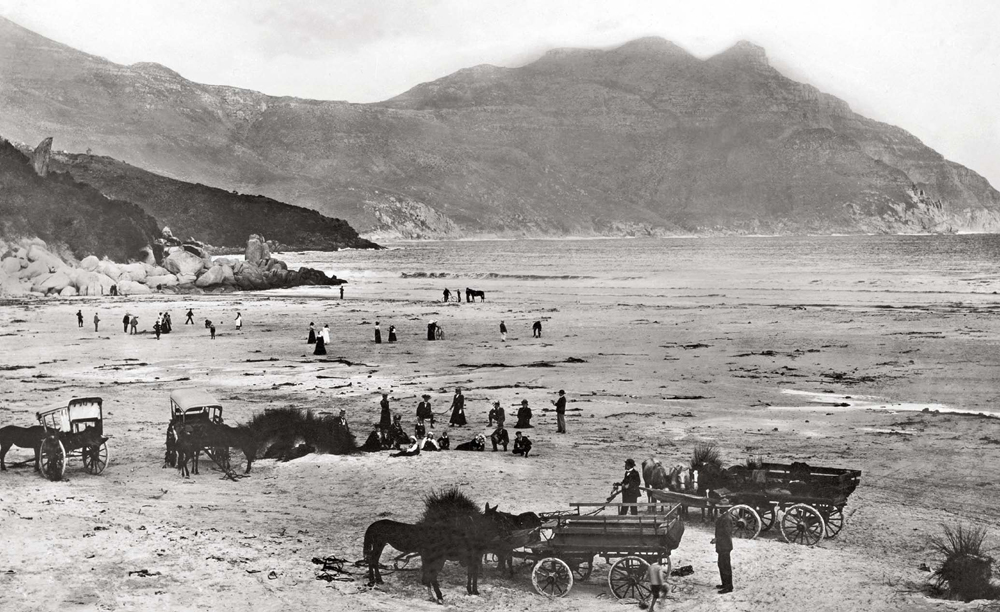

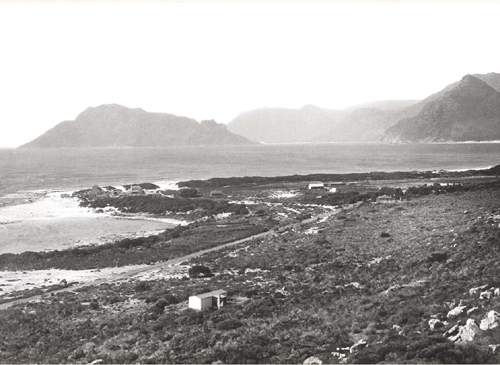

A view of Hout Bay around the turn of the twentieth century showing visitors on an outing to the bay. Note the two Cape carts with canvas hoods, unique to South Africa, which were widely used in the past.

In the background, at left, a natural pedestal of granite can be seen. A statue of a leopard, by local sculptor Ivan Mitford-Barberton, was placed on this rock in 1963 as a memorial to the many wild animals which once flourished in this area.

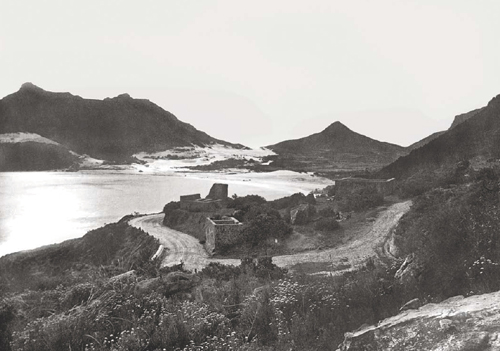

The East Fort in Hout Bay was one of two batteries constructed in 1781 when the Dutch feared that the British would invade the Cape. The western one was known as Sluysken, and the eastern as Gordon.

The Hout Bay forts saw action briefly when the British took the Cape in 1795. Commodore Blankett reported that he had arrived at Hout Bay on 15 September, and sailed towards the shore, ‘the enemy keeping up a smart fire from the two Batteries’.

The Dutch surrendered on 16 September, and all Dutch East India Company assets were handed over to the British. An inventory of these assets includes the following: ‘The post in the Hout Bay, with the cultivated Valley as far as the Mattrosen Drift; the Battery Sluysken; the Battery Gordon’.

Both forts fell into ruin in later years, but the East Fort, which housed a powder magazine and an officer’s quarters, has been restored as a tourist attraction.

The fishing village on the bay was probably established circa 1867, when a German immigrant named Jacob Trautman settled there. As well as farming, he began a fishing industry, salting fish for export to Mauritius.

Hout Bay remained an isolated but charming little village with almost no economic importance until the 1940s, when it became the centre of a lucrative commercial fishing enterprise. The harbour is still the centre of a tuna and crayfish industry today, and the Hout Bay valley has become a heavily populated residential area.

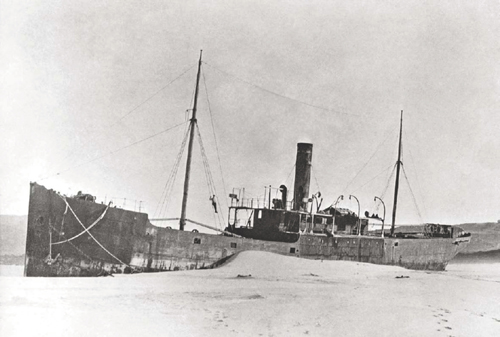

THE KAKAPO, A STEAMSHIP OF 1 093 tons under the command of Captain P Nicholayson, was on her maiden voyage from Swansea, Wales, to Sydney, Australia. When the ship left Cape Town on 25 May 1900 a northwesterly gale was blowing, and in the darkness the captain mistook Chapman’s Peak for Cape Point. He steamed full ahead, only to ground his ship on the sands of Noordhoek beach.

At the turn of the century Noordhoek was an isolated spot, with only a few farms in the area. At dawn, the crew of 20 men climbed from the ship onto the sand, and a few of them made their way to one of the farms to report what had happened.

It is said that the captain was so mortified by his error of judgement that he refused to leave the ship or to answer any questions.

Today the remains of the ship still lie on the sands above the high-water mark, and have become something of a tourist attraction.

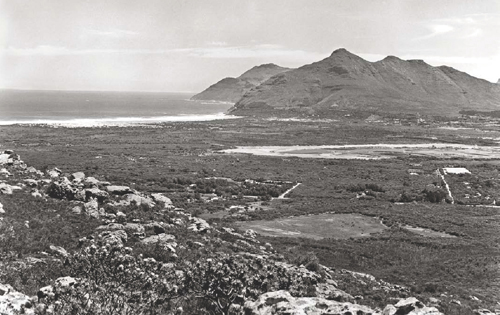

The first official reference to Noordhoek was in 1743, as part of a farm known as Slangkop (‘Snake Head’), occupied by Christina Diemer, the widow of Frederick Rossouw. In 1873 the area was divided into six lots, and the farmers concentrated mainly on growing vegetables to supply ships calling at Simon’s Town.

Initially, the name of the area was possibly Noorhoek (‘Norwegian Corner’), since the mountains of the southern Peninsula were known as the ‘Mountains of Norway’.

In 1902, an article in the Wynberg Times described the village and its surroundings. The writer mentions ‘nice farm-houses scattered all over, surrounded by cultivated gardens growing nearly every kind of vegetable’. He saw the wreck of the steamship Kakapo, and was impressed by the long, white beach. He concluded that Noordhoek was one of the most attractive places he had ever seen.

Kommetjie (‘small basin’ in Afrikaans) is a village clustered around a small, basin-like inlet on the Atlantic coast. There is evidence that it was used by prehistoric peoples as a natural fish trap. Some of the Khoisan people lived on Slangkop, the mountain that overlooks Kommetjie. The village itself, like Noordhoek, has its origins in a grant of land made in the middle of the eighteenth century to Christina Diemer.

Lord Charles Somerset, Governor of the Cape from 1814 to 1826, had a hunting lodge here. This building is now known as Honeysuckle Cottage.

The village is close to the Slangkop lighthouse. which was built in an attempt to reduce the number of shipwrecks in the area. Slangkop was commissioned in 1914, but not completed until 1919, and is the tallest cast-iron lighthouse on the South African coast. Today, Kommetjie is best known for its excellent surfing.

Kommetjie was relatively isolated until the early years of the twentieth centry, when a road was built around Slangkop. The image below shows the road under construction. Until that time, the only access to Kommetjie (and to the rest of the Noordhoek valley) was via a track over the Steenberg, along which the road now known as Ou Kaapse Weg (‘Old Cape Road’) was later constructed.

The Slangkop road provides a delightful view of the village, and across Chapman’s Bay to Hout Bay and the back of Table Mountain.

Cape Point, a nature reserve covering almost 8 000 hectares, is home to a rich diversity of fauna and flora, including many fynbos species of the Cape Floral Kingdom. Cape Point is part of the Table Mountain National Park, which has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Both the old and the new lighthouses can be seen in this photograph: the 1860 lighthouse stands poised on Vasco da Gama Peak, and the 1919 lighthouse, much lower down, on Dias Point.

The ‘new’ lighthouse at Cape Point is a reminder that the rocky headland is renowned for more than its scenic beauty. From the 1400s, when Bartolomeu Dias named it the ‘Cape of Storms’, Cape Point has been a landmark for seafarers. Many ships have been wrecked on the rocky coastline over the centuries, and the remains of some of these wrecks can still be seen.

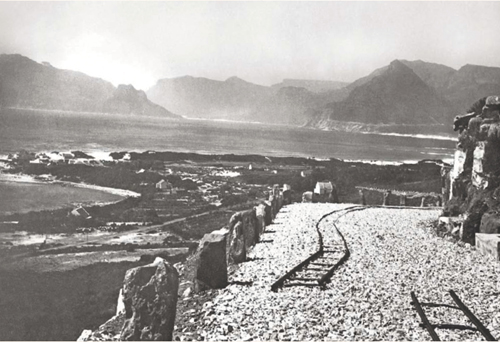

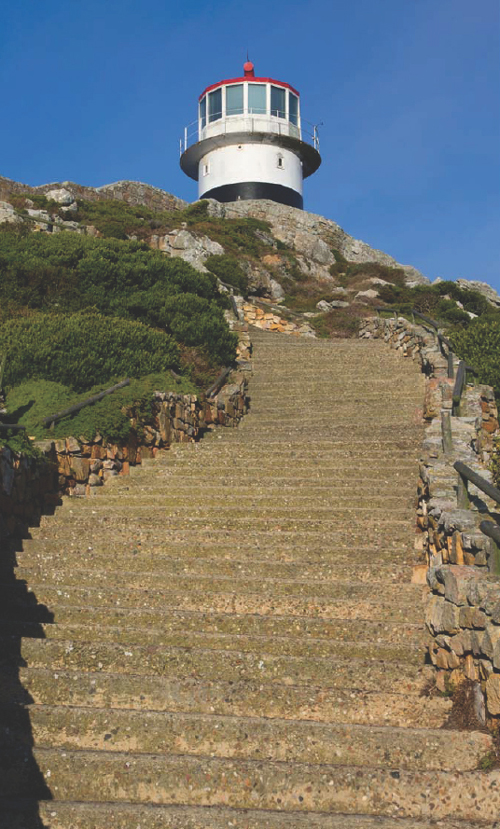

The original lighthouse at Cape Point was completed in 1860 and stood on the highest point of Vasco da Gama Peak (opposite page, left and right). However, its height above sea level meant that the light was often obscured by mist or fog. When, on 18 April 1911, the Portuguese liner Lusitania ran aground on Bellows Rock, with the loss of eight lives, it was decided to build a new lighthouse on Dias Point, only some 80 metres above sea level (above and opposite page, below).

The foundation stone of the new lighthouse was laid on 25 April 1914, and the lamp was first lit at sunset on 11 March 1919. This is the most powerful light on the South African coast and is visible from a distance of 34 nautical miles.

Cape Point, seen from the sea on a calm day. The Point was treated with great respect by mariners, who knew how dangerous it was, especially in foggy or stormy weather conditions. Contrary to what many people believe, this is not the meeting point of the Atlantic and Indian oceans. The cold Benguela current meets the warm Agulhas current at a point which fluctuates between Cape Point and Cape Agulhas.