The development of Simon’s Town (sometimes referred to as Simonstown) owes much to the fact that it is a safe natural harbour. In 1671, a Dutch ship, the Ysselsteijn, sheltered here from strong winds, and the captain reported the fact to the Dutch authorities in Batavia (Java). The bay, initially known as Ysselsteijn’s Bay, was surveyed by Simon van der Stel, the Governor of the Cape, in 1682, and renamed Simon’s Bay.

When the British took over the Cape for the second time, in 1805, their naval establishment was first based in Table Bay, but because Simon’s Bay offered a safe anchorage all year round the fleet was transferred to Simon’s Town in 1813.

Skilled Malay artisans came to work in Simon’s Town, and this was the beginning of the community which became known as Blacktown. In 1904 black workers were employed to build the East Dockyard and the Selborne Dry Docks, and were housed in Luyola (‘place of beauty’ in Xhosa) on the slopes of Red Hill. In the late 1960s, apartheid regulations led to the forced removal of ‘non-white’ residents to Ocean View, on the western side of the Peninsula.

Simon’s Town was the strategic base for the Royal Navy’s South Atlantic Station through both world wars. The base remained under British control until it was handed over to the South African Navy in 1957.

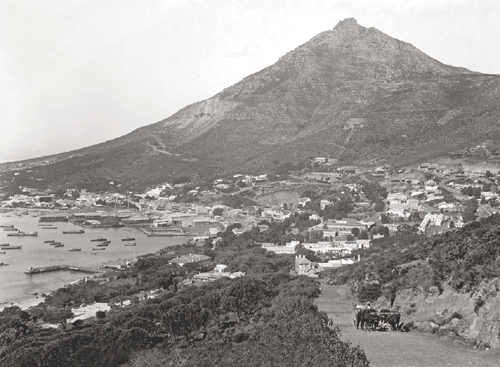

View across Simon’s Bay, circa 1910, probably taken from Blacktown, showing ships of the Royal Navy and smaller craft at anchor.

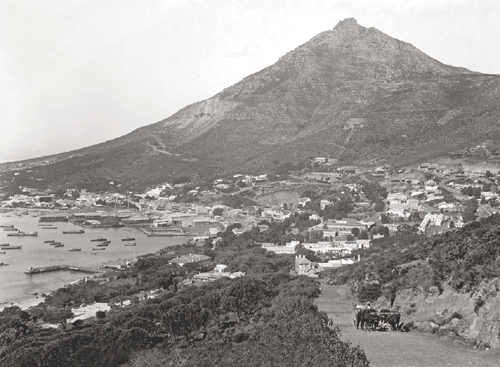

An aerial ropeway once ran between the Simon’s Town naval dockyard and the heights above the town. Work began on the ropeway in 1903. It was intended to transport patients, other passengers and stores from the West Dockyard to the naval hospital and sanatorium on Red Hill. The lower station was in the West Dockyard, the intermediate stop was at the Naval Hospital, and the terminus was the summit of Red Hill.

Initially the ropeway ran on wooden pylons, but these were replaced with steel in 1913. The engine house stood next to the Naval Hospital. The ropeway was first powered by a diesel motor and later by electricity.

The journey took 15 minutes, passing over St George’s Street on the way to the top station, and the passenger car could carry up to six passengers and an attendant. A goods car was used when stores were transported.

Mr Tom Downie was in charge of the ropeway from 1904, when it began operating, until 1927, when it stopped running. The ropeway was demolished in 1934, and only the small waiting room at the dockyard has been preserved.

Although over a hundred years separate these two photographs, the view is still substantially the same, even to the dormer windows and chimney pots of the former Dockyard Police building.

The British Hotel, opposite the main entrance to the Simon’s Town naval dockyard, is a reminder of Victorian days. This is the second hotel to be built on the site, and dates from 1898. After years of deterioration, a major fire and vandalism, the building was restored in 1991 to its former splendour.

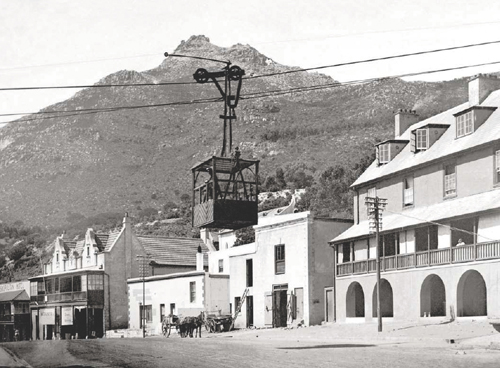

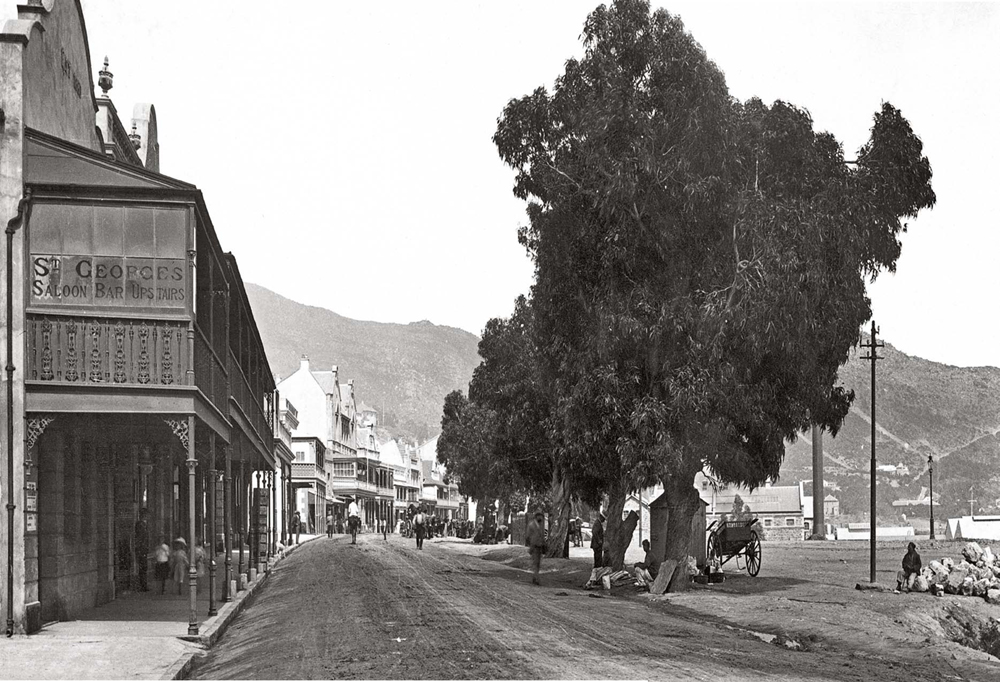

The main road through Simon’s Town changes its name several times. On entering the town it is called Station Road, thereafter becoming St George Street, and then finally Queen Street. A statue of the famous dog Just Nuisance stands in Jubilee Square, previously Market Square, which is to the right of these photographs. The trees in St George Street had been replaced with palm trees by the 1950s.

The bronze statue of Just Nuisance, weighing 75 kilograms, was commissioned by the Simon’s Town municipality. The work of local sculptor Jean Doyle, the statue on Jubilee Square was unveiled on 12 July 1985. The square was named in 1935 in honour of King George V’s Silver Jubilee.

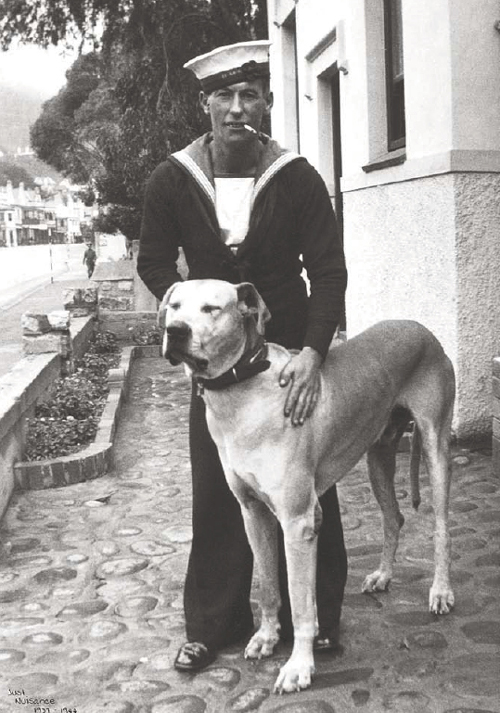

THE STORY OF JUST NUISANCE, the Great Dane who enlisted in the Royal Navy, is well known. His papers show that he ‘volunteered’ on 6 June 1939 for ‘the period of the present emergency’ (the Second World War). His trade was given as ‘bonecrusher’ and his religion as ‘scavenger’.

He accompanied sailors who travelled by train from Simon’s Town to Cape Town for a night out, and escorted them back when the pubs closed. On one occasion he saved the life of a sailor who had been attacked, barking at a taxi driver until the man realised that Nuisance wanted him to follow. Seeing the sailor lying unconscious, the taxi driver called an ambulance, and the sailor was taken to hospital, with Nuisance in attendance.

Nuisance was discharged from the service on 1 January 1944. He was gradually becoming paralysed as a result of a thrombosis. His condition continued to worsen until a veterinary surgeon advised that he be euthanised. He was buried at Klaver Camp, on nearby Red Hill, with full naval honours.

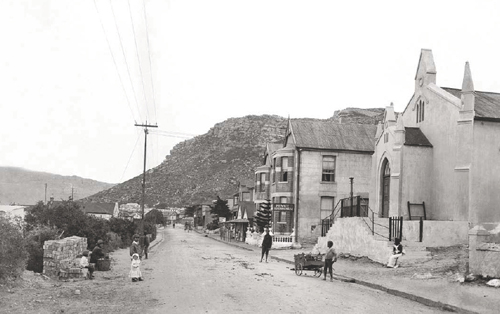

This view of Main Road, Kalk Bay, shows the Dutch Reformed church on the right. Kalk Bay, a natural harbour noted by Simon van der Stel in the 1680s, took its name from the many lime kilns established in the area (kalk is the Dutch word for lime). Lime burning began here in the 1670s, using the mussel shells and other seashells which lay on the beach. The free burghers who ran this enterprise sold the lime to the Dutch East India Company for use in construction work, charging three guilders a ton.

Kalk Bay also became a major fishing centre. Fish was caught and transported to Cape Town, where it formed the staple diet of the slaves. From about 1740, marine stores were transported from Cape Town to Kalk Bay by ox-wagon. From Kalk Bay these stores were conveyed by coaster to Simon’s Bay, which had become the winter anchorage for Company ships. In the early 1800s, a whaling station was established here.

Initially, in the 1840s, Dutch Reformed services were held in a private home and led by ministers from Wynberg. Kalk Bay was later incorporated into the Simon’s Town congregation, services being held in the hall of the Anglican Church. In 1875 the Dutch Reformed Church bought three lots of ground in Kalk Bay and on 26 April 1876 the small Dutch Reformed church was consecrated. Morning service was conducted by Dr EP Faure in Dutch, and the afternoon service by Dr Robertson in English.

The final service was held on 7 January 1950. The church building was sold and rezoned for business. Subsequently it housed various commercial enterprises and is now the Kalk Bay Theatre.

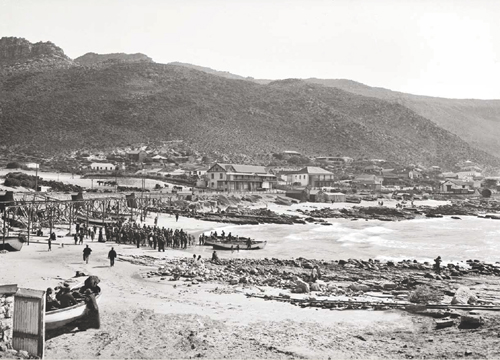

The busy scene on the beach at Kalk Bay in the early years of the twentieth century is in strong contrast with its appearance today. The present fishing harbour, with its breakwater and lighthouse, is a popular tourist attraction.

Whaling took place at Kalk Bay from the early 1800s. The huge southern right whale yielded, on average, 70 barrels of oil. The vats used to store the whale oil are clearly visible in early photographs. Whale bones were used for furniture and for fencing, and were also exported for use in corsets, shoehorns and umbrellas. In the mid-1820s, about 30 whales were killed and processed each season. (The season ran from August to November each year.)

In the 1840s, the fishing community at Kalk Bay was augmented by groups of emancipated slaves, many of whom had come originally from fishing communities in the East Indies. In the 1870s groups of Filipino sailors who had deserted from American ships also made this their home. The small bay became the centre of a fishing industry, the remnants of which still survive.

In the mid-1800s Kalk Bay became a fashionable resort, and in April 1851 was described in The Cape Monitor as a ‘salubrious and fashionable watering-place – the Brighton of the Cape’. The railway arrived on 5 May 1883, and this brought even more holidaymakers. In 1889 work began on the extension of the line to Clovelly. A stone viaduct was constructed, effectively cutting Fishery Beach in half and preventing fishermen from pulling their boats onto the shore.

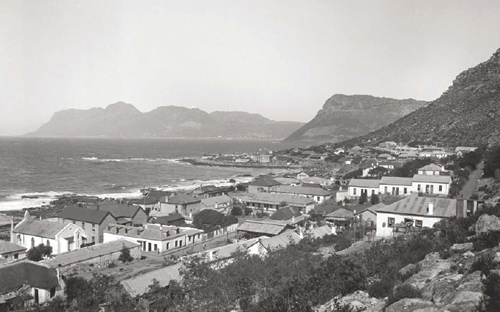

The view from Kalk Bay to Fish Hoek and Simon’s Town has not changed significantly in the past hundred years. Apart from the spread of housing, the major addition has been the Kalk Bay fishing harbour, with its breakwater, lighthouse and protected moorings.

THE COASTAL VILLAGE OF ST JAMES became a popular holiday resort for Cape Town’s elite in the early twentieth century. The St James Hotel, shown here circa 1910, was originally a large private residence named Le Rivage. A number of great cedar trees shaded the front of the house, one of which survived to the 1960s.

Situated right opposite St James station, the hotel was very popular with visitors because it was sheltered from the southeasterly wind.

Shortly after the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899–1902), the owner of the hotel, Captain Gently, began advertising dances ‘in the cool sea breezes’ with ‘first class floor, orchestra, bar and catering arrangements’. A number of guests travelled by train to these events, and Captain Gentry made a habit of serving coffee and biscuits to the stationmaster and the driver of the last train, as he accompanied his guests to the station. Today, the much-enlarged hotel is a retirement home.

Visible at the left of both photographs is St James Roman Catholic church, which was built in the 1880s. The parish of St James was established in 1859, and gave its name to the area.

Muizenberg began as an outpost on the banks of Zandvlei. Het Posthuys (‘the posthouse’), a tollhouse established here in 1673 by the Dutch East India Company, is considered one of the oldest buildings in South Africa. In 1743 a military post was established, and Wynand Muys, the sergeant in charge, gave his name to the area. Barracks, stables and a magazine were constructed. These buildings were later used by the British, and the ruins could still be seen in the early years of the twentieth century.

In the days of the Dutch East India Company, Muizenberg was known as a refreshment stop for those travelling from Cape Town to Simon’s Town. The Battle of Muizenberg, on 7 April 1795, when the British defeated the Dutch forces, marked the beginning of the first British occupation of the Cape. At this time there were only a handful of farms and a few fishing huts at Muizenberg.

From these small beginnings, Muizenberg developed into a holiday destination and an attractive suburb of Cape Town, which had the distinction of being the first to have a bus service (1902), a permanent cinema (the Electric Theatre, 1902) and airmail delivery of post (1911). In recent years, the face of Muizenberg has changed considerably. However, the sweep of its great beach – ‘white as sand of Muizenberg’, in the words of poet Rudyard Kipling – remains its greatest asset.

CAPE PREMIER CECIL JOHN RHODES bought this cottage in 1899 to use as a retreat in the hot summer months. Even when it was oppressively hot at his official residence, there were always cool sea breezes at Muizenberg.

Rhodes was ill when he returned (against the advice of his doctors) to the Cape in 1902 after a visit to England, and asked to be moved to his cottage where it would be a little cooler. Unfortunately the weather that year was unusually hot, so he had no relief from the intense heat. He died at his cottage on 26 March 1902.

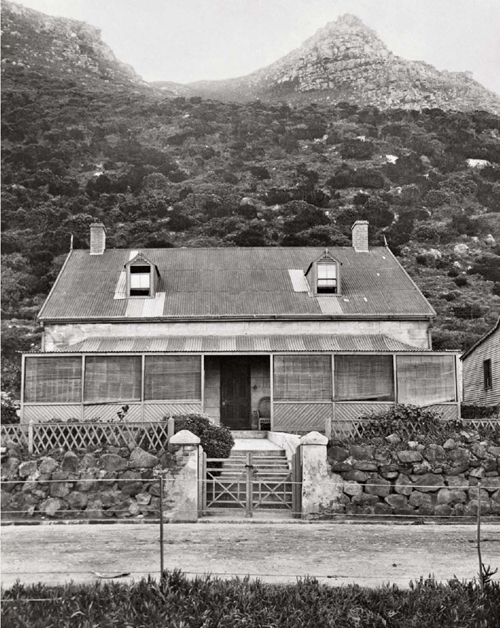

During Rhodes’ ownership, the cottage had a corrugated-iron roof with dormer windows at the front. After his death, the front dormers were removed and the corrugated iron replaced with thatch.

The cottage was unoccupied until 1932, when the Rhodes Trust gave it to the Northern Rhodesian government. Five years later, it was returned to the Cape Town city council as a gift. It was declared a heritage site the following year, and in 1953 was converted into a museum.

Muizenberg’s fine bathing beach became its greatest attraction in the 1890s, but its days as a seaside resort began in the 1820s, when Farmer Peck’s Inn became one of the first seaside hotels in the Cape.

Thousands of people travelled to Muizenberg on public holidays. After the Second Anglo-Boar war (1899–1902), it became such a popular destination that direct trains ran from Johannesburg, via a loop at Salt River, to Muizenberg station. In 1902 the jumble of private bathing huts was removed, and the municipality erected a neat row of bathing boxes. The amenities were completed by the building of a wooden pavilion in 1910.

A guidebook of 1914 describes the resort in glowing terms: ‘The sea is the complete renovator. It is the only cure-of-all-aches, there is nothing so tonic as a dip … and nothing so calculated to revive the sense of well-being than … to spend lazy hours on the Muizenberg sands.’

A tourist brochure of 1918 extolled the health benefits of surfing: ‘It steadies the nerves, exercises the muscles, and makes the enthusiast clear headed and clear eyed.’ Surfing is still a popular sport at Muizenberg today, particularly at Surfer’s Corner (shown above), where the slow, gentle waves are ideal for novices.