2 June 2018

Of all the years I spent at school and university, I recall with pleasure only those of primary school. I don’t mean that the rest of my education, up to my university graduation, was a waste of time: rather, I would emphasise how happy I was to discover Latin and Greek, philosophy, mathematics, chemistry, physics, geography and, especially, astronomy. School, and later university, had precisely that function: introducing me to branches of knowledge I was completely ignorant of. They said to me: there is a subject called Latin, or Greek, or philosophy, and you will study it for a certain number of years—five, three, even just one.

But it never seemed that knowing Latin or Greek had a value in itself; it meant, for example, being able to read the works of Euripides or Seneca in the language in which they were written. I considered them purely subjects for academic training; studying them was useful for getting a diploma, or for a possible job. It wasn’t learning, but a continuous obedient exercise that led to a position high up in the hierarchy of cleverness.

I was usually one of the best, and yet the ideas that I memorised in order to shine have all faded. I’ve forgotten everything, and I’m not happy about it: how much wasted struggle. Not only do I have nothing left in my head—I have the impression that I studied very hard without learning, that I made an enormous effort without a moment of enjoyment.

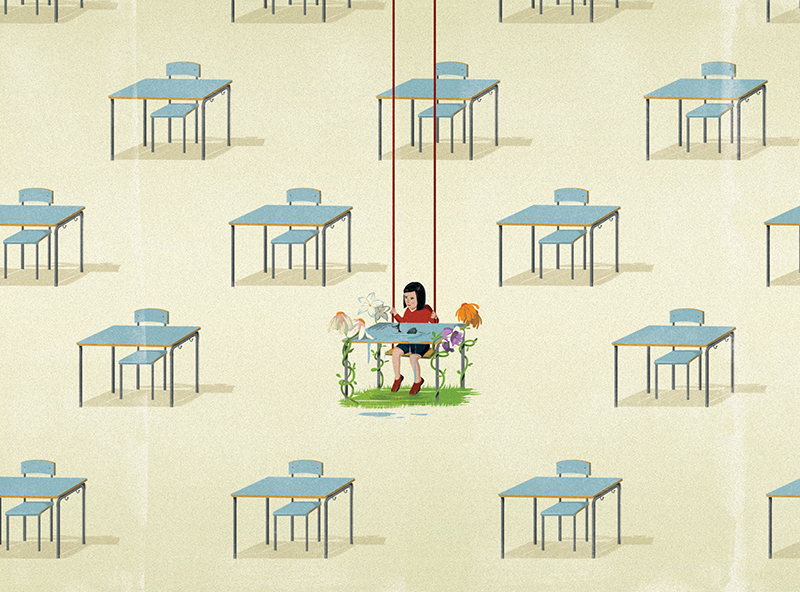

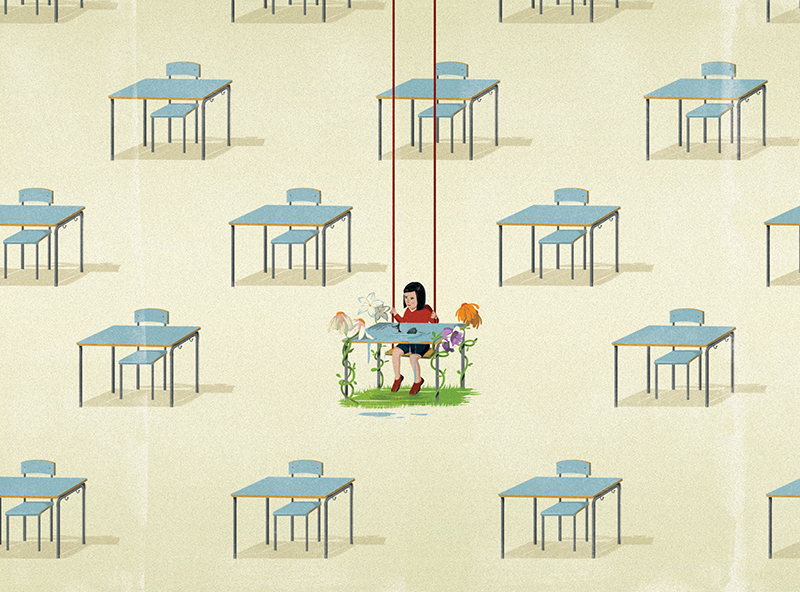

My primary school years, on the other hand, have left a very clear memory of the wonder with which the hours at the desk were transformed into precise skills—reading, writing, counting—but also into numerous additional bits of information. I wouldn’t today be able to describe in detail how that feeling of proud wonder took shape; there, too, memory has faded, and I’d have to invent convincing anecdotes, because I can’t remember any particular thing.

But the wonder—the wonder of knowing how to read, to write, to transform signs into things, landscapes, people, feelings, voices, or, vice versa, how to reduce all reality, and every fantasy, every plan, into signs of the alphabet, into numerals—the wonder has remained vivid and lasting. Of the years that followed, I remember the hard work, the anxiety to do well, some humiliations, some nasty failures, a number of successes—but never that satisfying sense of wonder.

To my surprise, I suddenly started to learn again some time after I graduated. It no longer happens these days, but I hope that in the free time of old age, the wonder will return.