Checkmate on Dickery

This chapter is heavily influenced by the twelve-step motto, “instincts on rampage balk at investigation.” We often resist seeing the deep-seated truths that our bad behaviors express, and when asked to consider how we’re being dicks, our defensive, knee-jerk reactions make us look even worse. For this reason, the Twelve Steps include the inventory: a self-assessment to acknowledge our personal assets and deficits. It’s only through honest appraisal that we see how we contribute to problems and conflicts. And awareness empowers us to change.

At first, many react to the inventory the way a hand responds to a hot flame; we recoil at the notion of surveying our behavior. The tendency is to equate self-inventory with accepting blame or practicing self-criticism. However, as they say in the business world, “not all inventories are written in red ink.” While assessing your flaws, account for your positive qualities as well. When it comes to a personal inventory, gifts, talents, and skills are just as valid as shortcomings.

Focusing on yourself can feel like going back to the scene of a crime, except not only are you the perpetrator, you’re the lead prosecutor. Some of us prefer to remain innocent until proven guilty—and deny everything. That sounds safer, but as we’ve learned, the cost of denial is too high. Rejecting responsibility for our actions locks us into our dickish moods and justifications for behaviors that put us in harm’s way. Ultimately, we become hardened in the belief that the world is out to get us, and isolate from others, including those who offer love, care, and support. To skip the personal inventory is to accept anxious apartness, a.k.a. loneliness.

Avoiding accountability for problems, issues, or conflicts in relationship provides serious cover for the sneak-attack that is isolation. Many of us feel a mind-boggling loneliness in bed with our long-term partner, the kind of quiet desperation that comes from fearing an invisible enemy who operates through guerilla warfare—shots fired at any given time or place, without warning, and from long range or point blank. These are the most fatal shots for relationships—and they derive from our unwillingness to leave our camouflaged position and take responsibility for our actions.

When done in tandem, the personal inventory and the accountability it creates allow for a safe space to drop the dickish attitude and codevelop ideas to promote intimacy and empathy. It’s like a cease-fire that’s followed by a peace treaty to end the war of isolation and loneliness.

I received an email that demonstrates this phenomenon from a client I worked with before and after she went to rehab. In her words:

When I got home from rehab, I was beyond unpleasant. That wasn’t so unusual given what my behavior was like before. But I thought I’d gotten better, so this was disappointing. What was really shocking though was that Jim was acting like a jerk, too.

I think I’d been feeling put upon because Jim kept reminding me of what great lengths he’d gone to care for me and the kids as I was bottoming out from alcohol. I got so sick of it. I mean, sure I was thankful, but his constant fishing for praise made it hard for me to take a breath and ask myself how I felt about where I was, and what I’d been through, and where I’m headed to now as a wife and mother. Eventually it felt like he was guilt-tripping me, and meanwhile he thought I seemed ungrateful. We both felt unheard, and even after all we’d been through, we questioned whether we could accept each other warts and all.

We’d never faced that question before. I’d been drunk for most of the last three years of our relationship, but ironically the question of whether we could stay together in my sobriety was among the biggest challenges we ever faced.

So I asked Jim to try the inventory thing, explaining that we would put our judgments down and talk about our roles in everything that was going on. We agreed to keep the focus on ourselves, like you said, and do a thorough review of our actions so we don’t leave anything out that might be in each other’s lists.

It was hard at first—scarier than the thought of losing him—but when I analyzed how crazy I’d acted since rehab, I had to admit to Jim that I was worried he’d stop loving me if I got well. Deep down, I dreaded that Jim only loved saving me. The fear was that by getting sober, I took away his role as the knight in shining armor, which seemed to bring him validation.

I’m sobbing by the time I get through telling Jim this. Then when I looked up, he was crying too. When it was Jim’s turn to do an inventory, he admitted to fearing that I could only love him in that knight’s role, and now that I was better, I’d find someone I didn’t associate with all the difficulties we’d gone through.

Okay with Being Okay

What this looks like well into recovery, of course, looks dramatically different. One day my client Anne asked, “What do I do now?” She’d been in substance abuse recovery for over ten years, she maintained a long-term abstinence from sexually compulsive behavior, and had worked through her caregiving addiction after divorcing her second husband. Both of her exes were raging dicks, but she had remarried a kind, generous man who reciprocated her love.

“You mean now that you’re no longer at war with the world?” I asked.

“Yeah,” replied Anne. “Now that I’ve learned to hit pause and feel raw and vulnerable with a man who loves the real me.”

We live in a culture that pathologizes us for feeling vulnerable. It disparages sincerity. Openheartedness and other forms of sensitivity are viewed as signs of weakness. And as a result, we don’t know how to live comfortably in emotional experiences. Feeling strongly about another person is crazy-making; we’re not geared to make sense of what’s going on in our hearts and minds, and all we want to do is get out of that state of feeling threatened in our own skin.

“What’s wrong with me, Dr. Borg?” asked Anne. “After all the work I’ve done to stop getting involved with basket-case men, why am I freaking out at getting what I’ve been saying I wanted for years?”

“It’s probably time to learn to be okay with being okay,” I said.

Sometimes we have to question whether the work that we do is about self-improvement, as we tend to believe, or rather self-acceptance. As long as we’re trying fix someone else’s difficulties, we cannot get a handle on our own, but eventually the time comes to get good with ourselves. Other people’s problems have operated as a distraction from what we’ve yet to accept about ourselves. But a personal inventory of our part in problematic relationships will make hiding these tendencies difficult at best.

“You’ve side-stepped the issue of self-acceptance again and again by getting caught up in what’s wrong with whatever dude has taken center stage in your life,” I said.

Anne grew up in a devoutly Catholic Italian-American household. Her father, a hardworking “tunnel rat,” worked in the New York City subway system. Her mother was a school teacher. They loved Anne and her sister, and for the most part they loved each other. But Anne’s parents were unable to express this love directly, and by the time Anne was a teenager, she had begun attracting older men who were physically and sexually abusive. The dangerous relationship dynamic decreased as she got older, yet rather than disappearing completely, it persisted in the cold and cruel treatment she suffered at the hands of her first two husbands, as well as several of the men she dated after she began therapy with me.

Anne believed she had grown up in a loving home and could not figure out why she kept replaying toxic relationships with men. However, upon analysis, and unbeknownst to Anne when she first began therapy, her parent’s inability to express their affection for her was interpreted as apathy and she wound up internalizing this suspicion as a statement of her worth. Combined with the abusive men she encountered in her adolescence was a history of drug and alcohol abuse, several police incidents, and despite an above-average intelligence, poor academic performances.

“I was crying out for help,” Anne said one day in therapy. “Each bad boyfriend, each call from a teacher, or police officer, or friend’s parent was met with a freaked-out paralysis by my parents. There was nothing that could happen that would make them be proactive. At least that’s how it felt.”

I wouldn’t say there’s no such thing as self-love; I would say, though, that the adult expression of self-love takes the form of relationships we invite into our lives. When we welcome dicks into our lives (or anyone who becomes some kind of distraction against knowing and accepting ourselves as we are), we make it difficult to see who we are, what we need, and what we want, especially in romantic relationships.

“I just gave up on getting anything and everything that I ever wanted or needed, especially from another person,” Anne said.

Being with dicks also justifies keeping our defenses up, making the process of self-inventory questionable at best.

“Therapy shifted things for me,” Anne said. “When I took an honest look at my old version of events, it began to feel incompatible with what I was seeing now. I had taken the way my parents treated me in my childhood so personally. What else could I do? Then I carried those horrible feelings into all my relationships. And each one confirmed the horrible thoughts I had about myself.”

The last thing Anne’s parents meant to do was neglect her and give her the impression that she had no value to them. But their own lives—busy lives full of personal, professional, and familial stressors—made reassuring Anne impossible in the ways she needed. Anne blamed herself for this, as neglected children often do, and recreated scenario after scenario in which her limited value was confirmed by the men she chose to be with.

It’s only when we put our defenses down that we’re able to take inventory to see others and ourselves as we truly are. And only with such awareness that we can realistically accept both ourselves and others. Anne saw herself as a person with limited, if any, value. She worked hard in therapy to confront, challenge, and let go of this sentiment. Nonetheless, accepting the love of her third husband required confronting that old image of herself that had tormented her for so long. Accepting this new image and her own lovability was a profound, anxiety-provoking challenge.

“Funny,” sighed Anne. “I guess now I’m the basket case.”

“Nope,” I retorted. “You’re just in a new relationship and affected by the experience of taking a real risk with someone who is beginning to matter.”

Navigating the Insecurity of Accepting the World As Is

Several years ago, it was popular in twelve-step circles for people to blurt out, “It’s not going to be okay—it already is.”

As I said in the beginning of this book, the message of all the world’s mystics regardless of religious or spiritual bent is that everything is okay. Perhaps we need not leave this outlook in the metaphysical realm and can consider it a way of experiencing the world when there is a balance between how we feel, act, and are responded to. You might say that being okay is a state of harmony between these aspects, which might explain why it’s so elusive. Instead of accepting that we’re already okay, we tend to make this a goal for some uncertain future.

After my client Doug received news that he and his husband Gerard had been approved to adopt an infant daughter, he started analyzing his marriage in this way. All the turmoil they had gone through acting out and mistreating each other was really a refusal to accept that everything was okay. Or as Gerard put it: “From when gay marriage was approved to the green lights each step of the way in the adoption process, every time things worked out in our favor, the relationship got worse.”

Why is it so hard to accept that we’re okay? Well, when we defend ourselves from the anxiety that comes with being close to someone, refusing to believe we’ll be unharmed by them, eventually even feeling safe in a relationship is hard. Most of us have no real sense of how much risk our emotional investments place us in. And though we have a whole psychological defense system designed to limit our awareness of this risk, there are times when our vulnerability can no longer be suppressed. To feel okay is to be aware of how much we cherish the relationships that allow us to feel like ourselves.

After this period of pain and disruption in their marriage, I asked Doug and Gerard to summarize what they’d taken from the experience.

“Could it be that caring about each other, and everything we’d built so far, felt so intense that all we could do to maintain our sanity was try to kill it?” Doug asked.

“Try to kill it is an understatement,” mused Gerard.

“I just couldn’t believe things were working out in our favor,” admitted Doug. “I thought I was helping, but I’m sure it felt more like meddling or sabotage than like actual help. I just had to mess with the process.”

“I was embarrassed,” said Gerard. “I couldn’t stand it that things were working out and I blamed you for that anxiety. I couldn’t be honest about how terrified I was that my wish to have a family was finally coming true. It was too much. Sometimes I really hated you.”

“I felt that,” said Doug. “Every hoop we squeezed through to get closer to our dreams also made us targets for people who would not accept us.”

“Yes,” agreed Gerard, “people like us.”

“Amazing what little trouble I had protecting myself against the ways the world seemed to be against me, against us,” Doug said. “But when all the lights were green, I realized it was me who couldn’t accept me, us, or our circumstance as we—as they—were.”

“I must have felt the same because even though I was the one really pushing to make this happen, I joined you in the bad behavior that kept screaming: You two have made a huge f—king mistake by going for it.”

“Risky stuff, trying to make all that happen,” Doug acknowledged.

“Accepting the hand life dealt us?” Gerard said.

“No, no—are you high? This was not supposed to happen,” Doug said. “There’s no way I actually thought we’d pull this off. I’m not sure when, if ever, I’m going to accept this.”

“Because it’s scary as hell?”

“Yeah, thanks for rubbing that in.”

Why We Can’t Just Keep to Our Side of the Street

Not everyone has an addiction, compulsion, or “allergy” to a substance or habit that introduces them to the Twelve Steps. But all can benefit from recovery lessons, so I’ll provide an overview of the steps I find most helpful in letting go of dickery, as well as a process to abstain from being a dick.

In the twelve-step model, taking inventory is how one learns about, accepts, and eventually corrects so-called “character defects.” It’s Step Four: Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. Think of it as an account of what needs cleaning up. Steps Five through Nine involve acting on that awareness. We hold ourselves responsible for past behaviors, as well as what drives and sustains them, and attain the will to remove these character defects while we make amends with those we’ve injured.

When this is all done, we reach what’s known in twelve-step jargon as the “keeping our side of the street clean” step. Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it, Step Ten, is most pertinent to our exploration. Also known as the “maintenance step,” it offers the recovering person an opportunity to put the awareness earned through inventory to use in daily life. Taking personal inventory and promptly admitting your wrongs is the golden rule to resist behavioral rationalizations that lead to dickery. This takes the accountability for our dickery fully off others, allowing us to see and break down the logic we’ve used to justify our stance toward others.

“No inventory taking” is jargon in the twelve-step community for sparing our partner from our judgments and criticism. The saying is a way to remind ourselves to not be dicks, which sometimes feels like an impossible task. I’ve found, though, that the best prevention against taking someone else’s inventory—your husband’s, your wife’s, your partner’s, your colleague’s, your pal’s—is (drum roll, please) taking your own.

Putting Yourself in a Position to be Hurt

Jeff was newly sober and complained bitterly about a boss who had miraculously not fired him for his unexplained absences, misuse of company funds, and defiant behavior during the extreme drinking and drug abuse that led to his bottom. His boss was a recovering alcoholic who understood addiction and believed that with patience and tolerance he could help when Jeff hit bottom. I listened to Jeff’s tirade, then asked, “What about you? How do you contribute to the problems between you and your boss?”

“What?” Jeff exclaimed in what sounded like righteous indignation.

Behaving like a dick always boomerangs right back, and Jeff’s difficulty accepting his boss’s tolerance and generosity was causing him more problems than his alcoholism. His boss understood the nature of alcohol-fueled assholery, but had a harder time being compassionate toward Jeff in his newly sober ingratitude.

In recovery, resentment is considered the most toxic emotion since it places us in a position to be hurt. Our resentment may offer an instant jolt of relief in the form of anger, but the blame is focused on an external target, and if we don’t account for our part in the situation, others will continue to protect themselves from us, leaving us alone in an intolerable state.

In Jeff’s case, he can’t get a handle on why the people he hurt have neither forgiven nor forgotten his destructive actions, despite the fact that he is now sober. The returns on his “purposeful forgetting” will diminish over time, however, so he has to make a deliberate effort to make things right.

Jeff, in his role as the garden-variety dick, felt consistently tempted to project his faults onto someone else, preferably someone near and dear who really needed an inventory.39 “After all,” he asked his boss, “didn’t you help me get sober to help yourself? Isn’t that what you twelve-step people do? Seems kind of self-serving, yeah?”

Jeff’s boss wasn’t buying Jeff’s attempts to celebrate himself for his grand accomplishment. Though relieved and supportive of Jeff’s recovery, he didn’t see sobriety as an excuse to continue rude, destructive behavior. “It’s what we do, Jeff. We help people who express a desire to be helped. But we don’t accept them stomping all over us and taking advantage of our generosity.”

“Aren’t I helping you by letting you help me?”

“Jeff, please. You’re acting like a jerk, and alcohol is no longer an excuse.”

“I know that. I’ve sobered up, thank you very much. It’s your expectations that are stressing me out.”

It sucks to accept our character defects and absorb feelings we’ve long tried to diminish. But so long as we see our flaws in others, and misperceive counterattacks as unprovoked attacks, we will remain isolated, at war with the world.

“That may be so, Jeff,” said his boss. “But now we have to figure out if your bad attitude is just a last vestige of your active addiction, or who you really are.”

“I don’t know if I can do this,” Jeff admitted.

“No one does.”

Intervening with your obsessions, compulsions, and character defects is also referred to as “cleaning house.” And in recovery, some identify the moment of honesty and discovery that comes afterward as “the end of isolation.” By putting our seemingly defensive, but ultimately offensive weapons down, we embrace the risk that others will accept us as we are, vulnerable and pained. We finally use authentic emotions to connect with others. Being honest and open about who we are, that willingness to share, is how we accept ourselves and others.

It was easy to rationalize our behaviors without a witness to help us off the ledge of self-deception. We used to tell ourselves, I’m not a dick—they are, clutching this survival mechanism if only because no one was looking.

Mapping Out Your Positive Attributes

Because we’ve been so averse to accepting others, ourselves, and the world as they are, it can take a couple passes at the inventory for us to realize how wonderful various aspects of our life may be. Our psychological defenses didn’t allow anything in, not the good, the bad, or anything in between. We were so busy protecting ourselves, we couldn’t discern friend from foe. And so often the surprise effect of an inventory is that we see ourselves as lovable.

This first glimpse has far-reaching possibilities. Being loved by someone else may be an entryway to loving ourselves. The inventory isn’t meant to strip us down and shame us for our dickery, but to open the door to a realm where we discover things about ourselves, our history, and the world around us that merit acceptance.

A powerful form of self-care, inventory asks you to look in the mirror, see how the pluses mitigate the minuses, and weigh for yourself the net results. Traits that you like or even love about yourself will help you recover from the things you dislike, hate, or feel embarrassed or ashamed about. That’s what I mean when I say this is an inside job.

Regular inventories result in being “right-sized”—practicing humility as a daily endeavor. You go about life recognizing that you’re neither better nor worse than others, interacting with people eye-to-eye as equals.

When all’s said and done, inventory is a wonderful thing. But to get that sense of balance, let’s counter what may seem like the negative side of self-reflection by mapping out the positives. Often with chronic dicks, the non-red ink part of the inventory—what I’m calling asset mapping—turns out to be more difficult than the “here’s what an asshole I am” part. And why is that? Our good qualities have caused many of us to be exploited, attacked, and envied in our past.

Some people don’t realize that envy is intolerable to receive as well. Unlike jealousy, a temporary emotion that blends desire with possessiveness, as in “I want what you got,” or “Don’t take what’s mine,” envy is a lasting bitterness in which we feel contempt over an unattainable desire and would just as soon destroy its source. Envy can also complicate our feelings about our own strengths and virtues, since our enviable qualities may have been exploited by some and resented by others in the past. Sometimes, being a dick provides a shelter from having to acknowledge our qualities and the complicated, hostile reactions they occasionally engender.

I had a client named Nicolás who was a womanizer par excellence. Good-looking, funny, and smart, he was an actor and bartender whose greatest turn on was emotionally unavailable women. The more rejected he felt, the longer his interest endured. If the unattainable woman was finally ensnared by his charm, he would then believe it was “different this time,” and he could change a partner’s emotionally distant ways. It would all come crashing down, of course. Almost every time, once the woman showed up emotionally, convinced by Nicolás’s obsessive efforts, he’d ghost her.

No one was more convinced than Nicolás that he was an incurable dick. He had no trouble criticizing himself, feeling remorse, diminishing his virtues, and self-diagnosing as a “narcissist and maybe even a sociopath.” At times he rampaged against himself. And I couldn’t argue against what his acting-out behavior confirmed. But I also believed Nicolás’s history told a more complicated story.

When Nicolás was five-years-old, his mother claimed that his father was unfaithful. It turned out, however, that Nicolás’s mother was the one who had an affair. She pushed his father away, and his dad moved out and took Nicolás’s older brother with him, leaving Nicolás to manage his mother’s misery himself. From that point on, Nicolás became his mom’s “Little Man.” As her caretaker, he put every virtue he possessed to service for his “sad mommy.”

Underneath Nicolás’s dickish behavior as an adult, he remained the dutiful caretaker he was as a kid. He ran through numerous women’s lives appearing to be the perfect partner, yet after a few sexual encounters he would disappear. Once in a while, this routine would hit a snag; he’d find a woman in deep emotional trouble and throw himself into her care. Inevitably, though, the relationship would fall apart and Nicolás would return to meaningless sexcapades fueled by indignation and righteousness.

“See! I’m a really bad guy,” he would say. “I’d be better off accepting that and acting accordingly.”

At first, Nicolás found it hard to believe I didn’t agree with his devastating assessment of himself. I refused to see him simply as a narcissist who should accept his fate and banish himself to the realm of the unlovable. I suggested Nicolás take an inventory of his behavior to acknowledge and address whatever drove his dickery. There, he discovered a lost, lonely child who no amount of acting out—using and abusing women—could get rid of.

In inventory, acknowledging the ways he’d been a “bad guy,” a “user,” or “a prick” was easy for Nicolás. The challenge was to accept himself as a loving and loveable person who was simply terrified to allow himself to be exposed to the overwhelming needs of others again.

Nicolás developed his pattern of dickery to hide his good qualities, to throw women off his track. But in the process, he hid these qualities from himself. It took a long time, and a lot of bruises—including a punch delivered by a woman he brought for an unannounced session of couple’s therapy with me—for Nicolás to finally see his good side. He acknowledged his fear that, “If anyone saw my kindness, I’d be right back in that boat I was in with my mom when my dad left.”

It will be a lifelong process for Nicolás to accept his non-dick status and trust that he will not be exploited for doing so. But Nicolás is committed to the inventory work he began with me, and occasionally he checks in to let me know he’s still allowing himself to love and be loved.

By All Means, Judge Each Other

Dick or not, we’ve all got built-in defense systems that take qualities we dislike in ourselves and, rather than deal with them, allow us to perceive those intolerable things in others. Colloquially, we call this projecting. We walk around in this state of anarchy every day, imposing the bitterness, hatred, and self-pity in us on others, ignoring hurt, sadness, and fear simmering in our minds. These unacknowledged, unaddressed, unshared, and uncontained feelings grow from molehills to mountains when left to pile up inside us. Still, we’re terrified that these emotions say something more than that we’re merely human.

We’re geared to adjust to difficult circumstances. Like a strange emotional superpower, we can take trauma and heartbreak, and construe that pain as others’ shortcomings rather than absorb its full burden of anger and self-loathing. It’s human nature, then, to judge one another. But if we recognize that these attitudes are just as much reflections of ourselves—our own failures and flaws—we ready ourselves for a healing mix of compassion and empathy. So, go right ahead. Judge away. Judge to your heart’s content, till the cows come home, until you’re all judged out, and can judge no more. But do so in love.

EXERCISE: ADDRESSING ROADBLOCKS TO INVENTORY

Taking inventory is less about our overt behavior and more about what it covers up. Because our deep fear of vulnerability has been blocked from our awareness, most of us have not considered, much less shared, what’s behind our dickery. So let’s hit pause, reflect, and write down the attitudes and behaviors that acted as roadblocks to this sort of personal inventory.

Think of a recent time when you were a dick to someone important in your life—a romantic partner, colleague, family member, or friend. Write down your immediate reflections and feelings regarding your part (and only your part) in the incident:

Now without overthinking it, answer the following questions:

• What are your initial thoughts about what you wrote?

• How has identifying, reflecting upon, and writing about your part in the problem changed your perspective? Looking at the bigger picture, is the problem is acute or ongoing? And if so, do you have any idea why?

• Are you concerned that taking responsibility for past actions could damage significant relationships in your life? Has this happened before? Have there been threats to end relationships when you’ve admitted fault?

EXERCISE: POSITIVE MEMORIES MAKE STRONG FOUNDATIONS

Having behaved like dicks makes it obvious what was wrong with a relationship, and who bears responsibility for its failings. But few of us were always like that. Think back on your relationship with the person involved in the incident reflected on in the Roadblocks to Inventory exercise. Was there a time when you both felt more positive about one another? Remember the time before the negative experiences started to build up: a particular occasion when you did something together that went well and you enjoyed being together, a warm, connected feeling. This could be an experience had while traveling, an important life event, a tender romantic memory, or a time spent doing a favorite activity at home.

Now take a few minutes and come up with your version of that story, your part in what was good about it, with the goal to remember and visualize the experience as vividly as possible, focusing on warm, loving feelings, gratitude, appreciation, and so on. Next, write down the three most positive aspects of the experience.

EXERCISE: AFFIRMATIONS

Let’s consider the many positive qualities you possess. We’re putting this up against your history of dickery, so let us be generous as we recognize ways in which you’re loving, caring, trustworthy, and even loveable.

Example:

I have a good sense of humor.

Note the difference in how you see and feel about yourself when inventory is done in red ink—the standard inventory you’ve done all along by believing you were terrible—versus how you think of yourself after an inventory in black ink. Asset mapping balances you out. Spend some time jotting down thoughts on how you can maintain this feeling:

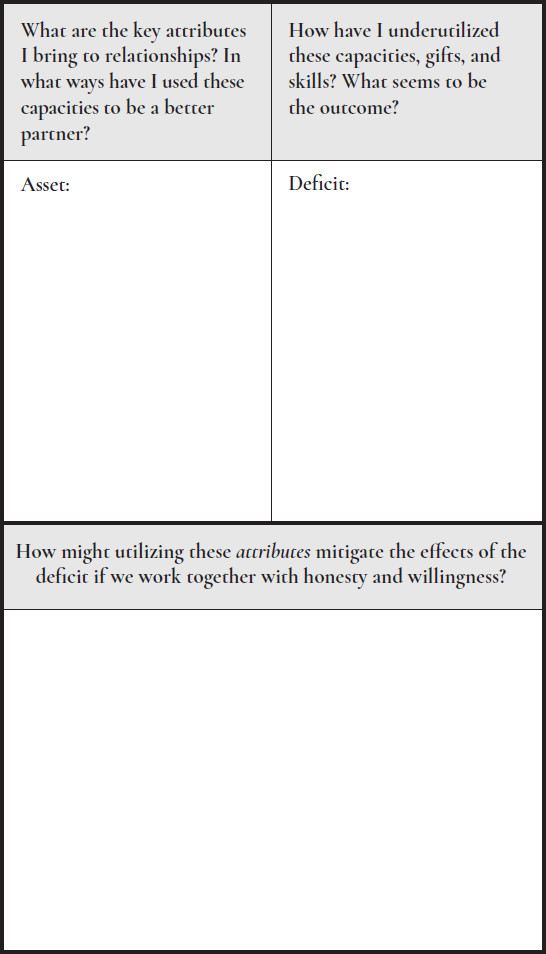

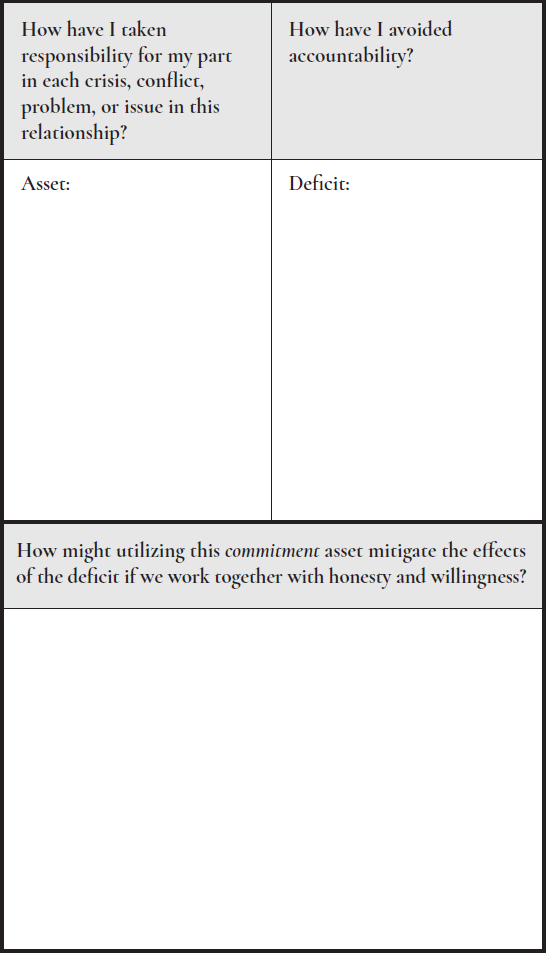

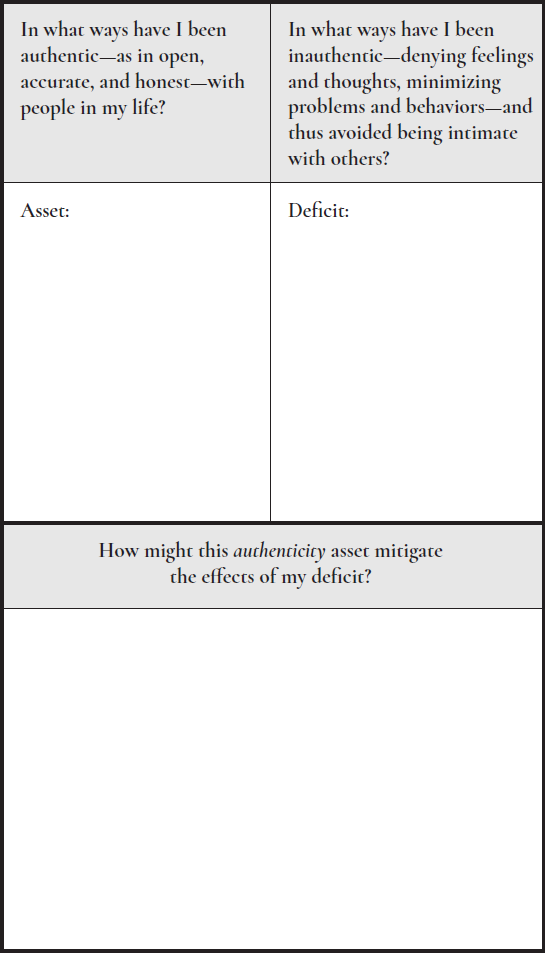

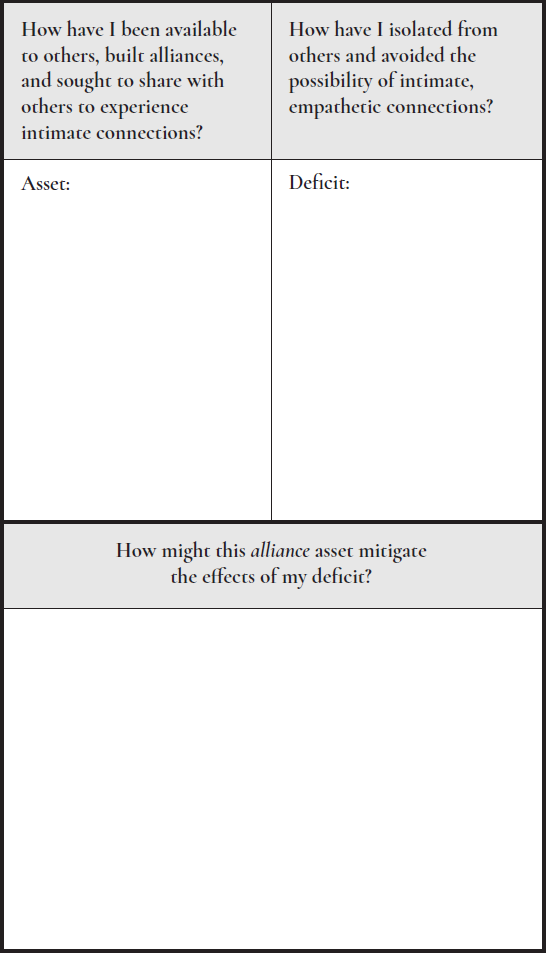

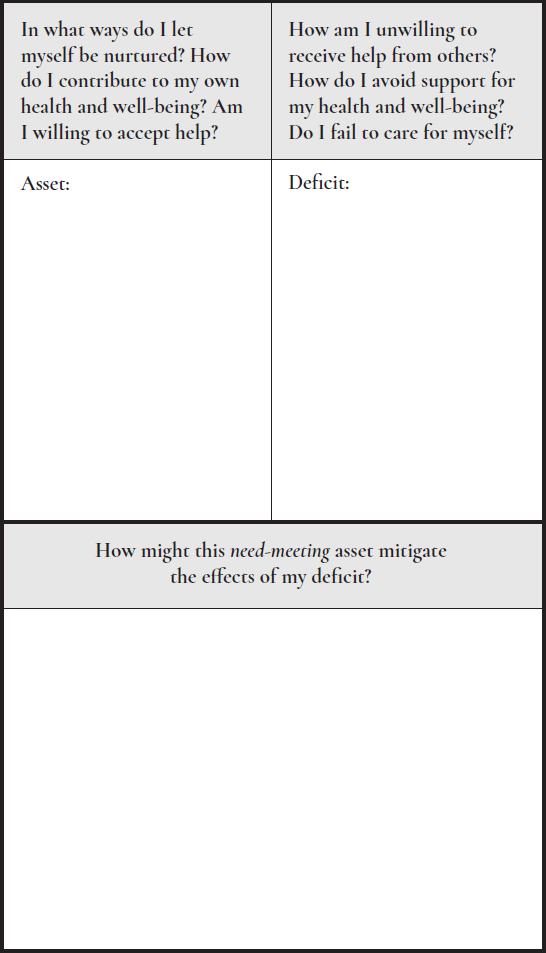

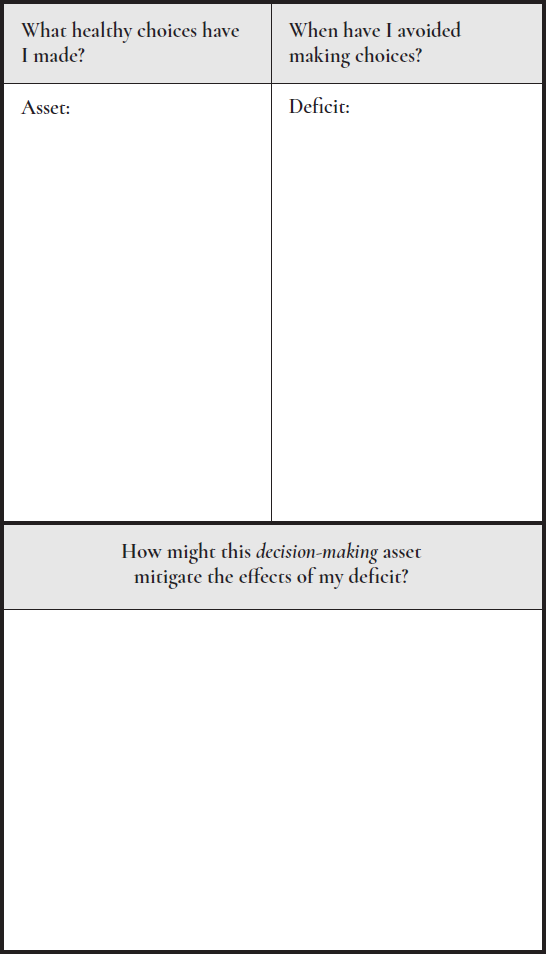

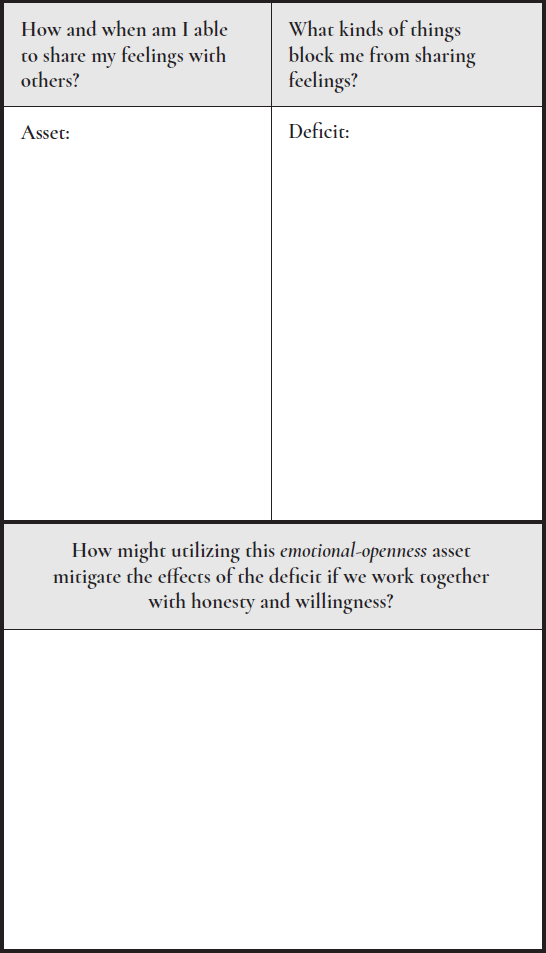

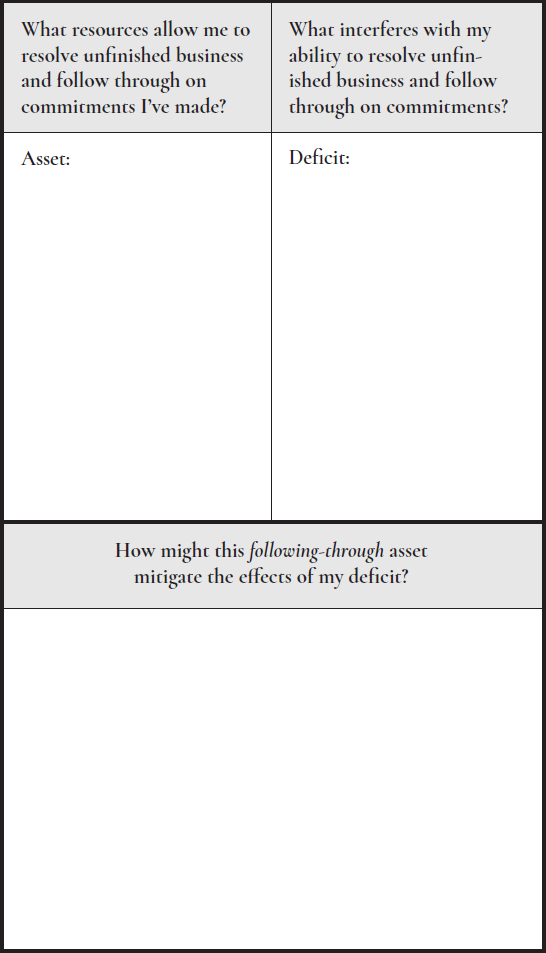

EXERCISE: ASSET MAPPING

Now that we have a sense of what our assets are, let’s put some of these attributes up against broad brush strokes of dickery in your past to see how the assets can better impact your relationships. As you know, being a dick can sneakily affect mundane, everyday activities.

In the left column, record your strengths; in the right, areas that still need improving. In each case, pause to consider the balance of these assets and deficits to gauge how you may use your resources to work through and let go of the defensive dickery.

Now, answer the following questions:

• Do you overemphasize your faults, or is your inventory accurate?

• If you focus too much on negative experiences, write down some examples of positive experience you’ve had in the past few weeks.

• Observe your self-talk. Consider ways to change negative self-talk into something positive that is still believable.

• When you notice yourself drifting into negative thoughts, ask if they really make sense. What happens when you challenge those thoughts? Can you find better ways to look at situations and people?