Electron Flow Theory

A solid understanding of electricity begins at the atomic level. Matter is composed of atoms, which are the smallest particles that elements can be broken into and still retain the properties of that element. An atom is itself broken into even smaller components, called subatomic particles.

Two subatomic particles are found within the nucleus: protons and neutrons. Protons have a positive charge, and neutrons are neutrally charged. The nucleus is the heaviest part of the atom and accounts for the majority of the atom’s mass. Electrons, the third type of subatomic particle, are in motion around the nucleus and have a negative charge. For a neutral atom, there is one electron for each proton that resides in the nucleus. From static shock to a lightning strike, all electricity is the movement of electrons.

The electrons occupy various energy levels around the nucleus, known as shells, and each time one becomes full, a new one is begun. The outer shell of an atom is known as its valence shell, and the number of electrons that reside in the valence shell are what determines whether an element is a conductor, a semiconductor, or an insulator. In many elements, the valence shell holds a maximum of eight electrons.

Boron, a Conductor; Silicon, a Semiconductor; and Phosphorus, an Insulator

A conductor is an element that allows electrons to flow freely. What all conductors have in common is one or more mobile valence electrons per atom that are free to move from one atom to another, as each valence shell has more empty spots than electrons. An insulator has a valence shell that is more than half full, or is completely full. It does not conduct electricity much at all, because its electrons are all tightly bound and will not leave their packed valence shells. A semiconductor, with a valence shell that is exactly half full, is neither a good conductor nor a good insulator, but it has some remarkable properties that make it very useful for making electronic components.

A convenient way of visualizing how electricity works is to imagine the electrons as drops of water flowing through a pipe. Such a flow is due to applied pressure on one end, forcing the water the opposite way. Likewise, when a conductor is connected across the terminals of the battery, the negative terminal of the battery applies a repulsive pressure on the electrons and pushes them towards the positive terminal. (A basic rule of electricity is that like charges repel each other, while opposite charges attract each other.) The resulting flow of electrons through a conductor is an electric current.

Current

The rate of flow of electrons through a conductor is known as current. Just as the gush of water through a pipe has a current, so does the flow of electricity. When you turn on a faucet, it’s easy to distinguish between a trickle and a roaring flood by the very different amounts of water flowing out each moment. Electrical current, similarly, is measured by the amount of charge flowing past per unit of time. Current is measured in amperes, or amps for short, and an ampere is defined as one coulomb (C), the basic unit of electrical charge, flowing past a given point in one second. The symbol used for amperes is A. If five coulombs of charge were to pass by a point every second, this would be a current of five amps (5 A).

Try your hand at this EI question.

-

What would be the current if 18 coulombs passed by in three seconds? - 3 A

- 6 A

- 18 A

- 54 A

Explanation

The correct answer is (B). Since 18 C of charge pass by in 3 s (that is, seconds), there must be 6 C passing by per 1 s. By definition, that’s a current of 6 A.

One coulomb, incidentally, is the amount of negative charge in 6.25 × 1018 or 6,250,000,000,000,000,000 electrons. It takes this many electrons flowing past a point in a conductor every second for a modest one ampere of current to be flowing. Current can be measured using a device called an ammeter.

Voltage

In order to make electrons move through a conductor, there must be a force that causes them to move. Water will move from a high-pressure area in a pipe toward a lower-pressure area, but if the pressure is equal at both ends, no movement takes place. Electricity is no different. There must be electrical “pressure” applied to a conductor to cause electrons to move.

For an electron, the “pressure” is caused by electromagnetic repulsion from a large negative charge, like that found at the negative terminal of a battery. This negative terminal has a huge excess of electrons, all pushing at each other. When a piece of conducting wire connects the positive and negative terminals of a battery (known as “completing the circuit”), electrons are pushed from the negative terminal into the wire, themselves pushing along the conducting electrons already there, and so on down the line, so that every electron will eventually reach the positive terminal, where there is a shortage of electrons and an excess of attractive protons pulling the electrons in. This will continue until the excess of electrons at the negative terminal is exhausted, and the battery is dead.

Electrical pressure is known as voltage, and it is measured in volts (symbolized by the letter V). The higher the voltage that is applied to a conductor, the greater the electrical pressure the electrons will experience, and the higher the current (rate of flow of electrons) will tend to be. Voltage and current are therefore directly proportional.

To be more exact, voltage is really the difference in electric pressure between two points, such that electrons will tend to be pushed from areas of greater electric potential (the proper term for this pressure-like quantity) to areas of lesser electric potential (lower pressure). For this reason, voltage is also known as electrical potential difference. It’s also referred sometimes as electromotive force. A technician would measure voltage using a voltmeter.

Resistance

Opposition to the flow of current is known as resistance. Resistance is measured in ohms, and one ohm is defined as the amount of resistance that will allow one ampere of current to flow if one volt of electrical pressure is placed on a conductor. The symbol for the ohm is Ω (the Greek letter omega), and resistance can be measured using an ohmmeter.

As resistance in a conductor increases, current flow decreases. This means that current and resistance are inversely proportional. The smaller the resistance a material has, the better a conductor it is. But voltage and current, remember, are directly proportional. Any time voltage increases, current will also increase. So in materials with high resistance (that is, in poorer conductors), a higher voltage must be used to get the same current.

All conductors have a certain amount of resistance, with some having more than others. Three materials that are most often used as conductors are silver, copper, and aluminum. Of these three, silver is the best conductor as it exhibits the lowest resistance. Unfortunately, silver is relatively expensive, so the next best choice is copper. Copper has only a slightly higher resistance than silver, but is much less expensive. Most electrical cable and wire is currently made from copper. Aluminum has a higher resistance than copper, and exhibits some other characteristics that make it even less than desirable for use in electrical applications. While aluminum was used extensively in residential wiring at one time, it is now used only in a few select applications.

Exceptions and Additional Notes

The analogy of electron flow to the flow of water through a pipe is helpful, but like all analogies, there are places where it breaks down. For example, when a pipe is broken, water will spray out, but when a conducting wire in an electronic device is broken, current flow simply stops along that path. That’s because electricity travels through the conducting metal of a wire, not inside a hollow pipe like water does. With no conducting material, electrons cannot move forward, and air molecules are very poor conductors. Except when the gap is very small (spark plugs are designed this way) or the amount of voltage extremely large (as occurs with lightning), an electric current will not flow through air.

Another interesting quirk in the study of electricity is what’s known as conventional current, which is defined by the (imaginary) flow of positive charge and is opposite in direction to actual electron flow. This strange concept came about because of the difficulty in actually observing electricity at a microscopic level.

Seeing and feeling the direction that water is moving in is easy enough, but electricity is another story. When scientists first started studying electricity seriously, not enough was known about atoms yet, and they realized that either a flow of negative electrons in one direction or a flow of positive protons in the opposite direction could explain the movement of charges discovered to be at the heart of electricity.

Scientists took a guess that it was the protons that moved, and defined the direction of current based on that. Later they discovered that protons stay in the nucleus and don’t move, but current direction had already been defined this way. As a result, if a circuit has a conventional current that is moving in a clockwise direction, this means that, in reality, electrons are moving around the circuit in a counter-clockwise direction. Nowadays, we can refer to either conventional current or electron flow, but it’s necessary to remember to switch the direction when going from one to the other.

It is straightforward to think of electrical current as a flow of electrons, but an individual electron does not necessarily traverse an entire circuit. Often this is more like a relay race as subsequent electrons carry the charge onward. Some references may, therefore, refer to the flow of a charge.

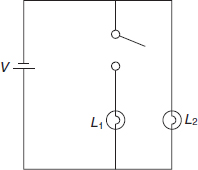

This chapter hasn’t discussed circuits yet, but you still have enough information to understand the worked example below. In the diagram, V stands for a source of voltage, such as a battery cell, and L1 and L2 are lamps connected to that voltage source. An unbroken line means an unbroken connection, and a broken line means a broken connection.

| Question | Analysis |

| In the wiring diagram pictured, which of the lamps will be lit up? | Step 1: The question asks which lamp will light up—that is, which will receive a flow of current. |

|

Step 2: The open switch (the break in the middle line) prevents current from flowing across the path containing lamp L1. That’s because current cannot flow into a dead end. However the path from the battery cell, through L2, and back to the opposite terminal of the battery does make a complete circuit. L1 should not have a current passing through it, so will not be lit up. L2 should have a current passing through it, so will be expected to light up. |

| Step 3: Since there are no gaps in its path, L2 should be lit up, but L1 should not. | |

| (A) L1 only will be lit. (B) L2 only will be lit. (C) L1 and L2 will both be lit. (D) Neither lamp will be lit. |

Step 4: Choose option (B). |

Now try one on your own.

-

Certain conducting materials decrease in resistance as the wires heat up. As resistance decreases, which of the following would be expected to happen? - The amount of current should increase.

- The amount of current should decrease.

- The direction of current should switch.

- The current should remain constant.

Explanation

The answer is (A). Resistance and current are inversely proportional, so when resistance decreases, current increases. Remember that resistance is so called because it resists current. If the resistance is less, it makes sense that the amount of current is able to increase, similar to how the rate of traffic flow is greater on the highway where there are fewer traffic lights.