It was Snow who remembered Makena’s birthday. There was a promotional calendar on the wall of their shanty, illustrated with photos of Kenyan wildlife. June’s animal was a warthog. When Snow blasted her awake on the third, belting out Stevie Wonder’s birthday anthem as if turning twelve in Mathare Valley was an event worth celebrating, Makena’s gaze went straight to the warthog. It looked the way she felt. If she’d had a pillow, she would have buried her head under it.

But Snow was irrepressible. Even their roommates, rubbing sleep from their eyes, were smiling. They sang in Swahili:

Afya njema na furaha

Afya njema na furaha

Afya njema na furaha mpendwa wetu, Makena

Afya njema na furaha mpendwa wetu, Makena

Maisha bora marefu

Maisha bora marefu

Maisha bora na marefu mpendwa wetu, Makena

Maisha bora na marefu mpendwa wetu, Makena

‘Today is going to be a day of at least six magic moments, starting with the dawn,’ declared Snow after they’d wished Makena good health and happiness and a long and fruitful life. ‘I’ve just peeped out and the sun has put on his best scarlet finery especially for you. After you’ve watched his show, we’ve clubbed together to pay for a shower for you in the public bathroom. First, though, you have to open your gift.’

She handed Makena a parcel wrapped in newspaper and tied with string.

Makena was deeply moved. Snow had nothing. In fact, she had less than nothing. Makena knew how much thought and effort would have gone into finding clean newspaper and string, let alone whatever was inside.

‘Open it!’ urged Janeth. ‘I can’t bear the suspense.’

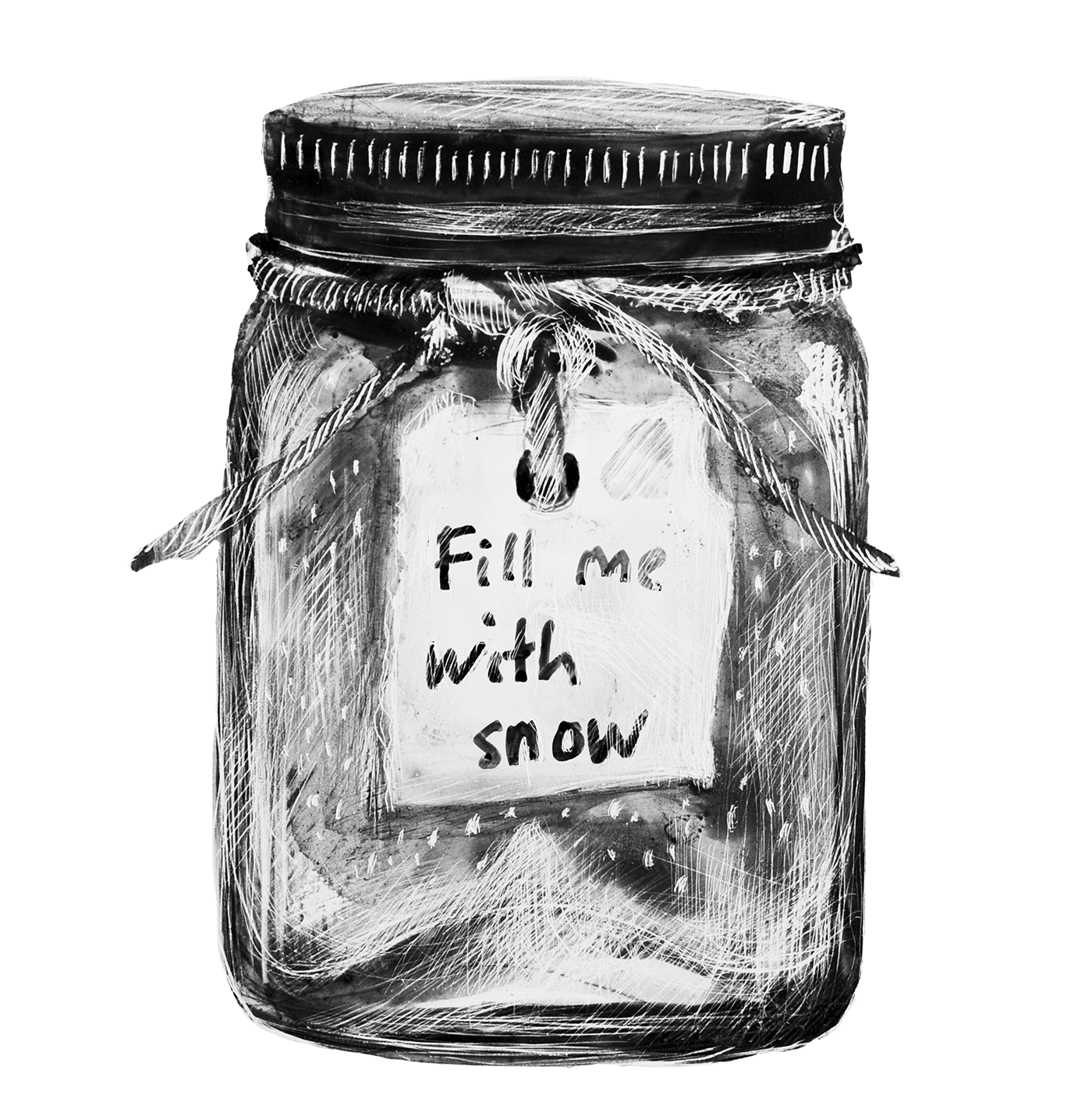

Makena removed the paper as if it was gold leaf not the sports page of the Daily Nation. Inside was an empty jam jar. A label made from a torn scrap of cardboard had been tied to the lid: ‘FILL ME WITH SNOW’.

Her roommates were shaking their heads. ‘An empty jar? We are poor but you would have been better off giving her nothing. What snow is she going to fill it with, Diana? Are you going to climb inside?’

Makena was so choked up she could barely speak. ‘It’s a long story and one for another day. But I promise you that if Snow was a millionaire, she could not have bought me anything more special than this jar.’

She hugged her friend tight. ‘Thanks, Snow. I’ll keep it always. One day I’ll find a way to fill it.’

In Mathare, there were two types of people. Those who lived by the motto: Mwenye meno makali ndiye mmaliza nyama: the person with the sharpest teeth is the one who finishes the meat. And those who believed the saying Msafiri mbali, hupita jabali: one who travels widely will pass the mountain.

To Makena’s amazement, most people fell into the second category. The rays of light and love that shone through the darkness of Mathare were a source of daily wonder to her. Hope was everywhere. It found its way up through the dirt and desperation like a wildflower struggling through a crack in an inner-city pavement.

The slum school nearest her shanty bore no resemblance to the one she’d attended. Optimistically named Success Academy, it was more barn than place of learning. Sheets of rusting iron were welded together to form a long, narrow structure barely bigger than Makena’s old classroom. Two hundred children crowded into it. There were no desks or chairs. Girls and boys of all ages sat on the dirt and shared a single toilet – a putrid hole in the ground with a metal screen.

Despite this, the pupils smiled more readily than any she’d ever known and the teachers were smartly turned out and dedicated.

One newly qualified teacher lived near Makena by the river. Every day she emerged beaming from her rickety shack and set off to the school. Makena watched her go with a lump the size of a golf ball in her throat. Some mornings it was all she could do to keep from running up to the woman and sobbing: ‘My mama was a teacher too.’

Many slum women scraped a living selling bags of grain or beans, or making crafts from scavenged soda cans, cloth and leather. They nodded over their wares late into Mathare Valley’s firelit evenings, hoping a customer less poverty-stricken than themselves would help them feed their hungry children.

It was deadly business. Nightly, they ran the gauntlet of the dreadlocked, machete-wielding Mungiki. The Taliban, who prowled the alleys seeking ‘protection money’ from slum residents, could be just as brutal. The lives of these women were short and unimaginably hard, yet they laughed more often and with a more intense joy than any Makena had seen out shopping in the fancy stores of Nairobi.

As she and Snow picked their way through the crowded, broken alleys that afternoon, the red dirt squares between rang with cheers and groans as the boys fought fierce games using a jwala, a football made from tightly wound plastic bags and twine.

Every boy in the slum dreamed of wearing the green and yellow uniform of Mathare United Football Club, one of Kenya’s top teams. The best showed off their skills in the hope they’d be spotted by scouts from Manchester United and other legendary clubs. For most, it was their only chance of ever escaping the slum.

Snow gave a live commentary on the game as they walked. Makena barely heard her. She’d been in the slum nearly a month but she’d never lost the feeling of being prey, and not just because she was scared the Reaper would come hunting for her. There were eyes watching in every corner of Mathare Valley. Many were friendly or indifferent, but some were calculating.

Makena feared more for Snow than for herself. Mathare Valley was packed with refugees from countries such as Tanzania and Malawi where children with albinism were being kidnapped daily. She’d heard whispers in the slum, where some talked of Snow as a ‘zero’ or an ‘invisible’. Snow pretended not to hear them, but the night sweats she suffered betrayed her secret terror that she was worth more dead than alive.

They passed the last of the shanties and climbed the rocky path to the rim of the crater in which the slum sprawled. When they reached the grassy summit, the view left them spellbound for all the wrong reasons. Seen from above, the shanties and mud shacks were packed so closely together that they appeared to share a single roof. A pall of smog and nyama choma cooking smoke hung over it.

‘Mathare’s other name is Kosovo,’ Snow told her. ‘You know, like the European country where they had a big war. When people in Mathare saw the bombed-out buildings and concentration camps on the news, they said: “That looks just like our home!”’

Surrounding Mathare were tilting blocks of social housing, crumbling and riddled with crime. Between them were still more of Nairobi’s two hundred slums, more pits of lawlessness and misery. Kibera, Nubian for ‘forest’ or ‘jungle’, was the largest in Africa and among the biggest in the world.

Makena shivered, not just at the sight of them but because she had cramps. Janeth and Eunice had given her a bag of hot mandazi – pillowy, deep-fried pyramids of dough dusted in icing sugar, all to herself. Her stomach was in shock. It hadn’t been full for weeks. A film of sweat shone on her skin.

The cramps faded and she smiled at Snow. ‘Thanks to you, Eunice and Janeth, I’ve had five magic moments already today: a snow jar, a beautiful sunrise, a shower, mandazi and The Karate Kid.’

They’d had a fun afternoon at the Slum Cinema, watching Ralph Macchio defeat his Cobra Kai opponent on a crackling, pirated DVD.

Beneath her floppy hat, Snow was rubbing aloe on her arms and face to soothe the sunburn on her pale skin. ‘You have at least one more magic moment to come. There’s the sunset, obviously, but I think we can stretch to a couple more.’

She fixed Makena with one of her intense looks. ‘You miss your mountains, don’t you?’

‘A little,’ admitted Makena. To her, the mountains and her father had been one and the same thing, as if the same ancient lava crackled through their seams.

‘A lot. What did you say the highest peak on Mount Kenya is called? Bat something.’

‘Batian.’

‘Right.’ Snow sprang lightly up to the summit of the tallest heap of rubbish. ‘Come up here. Let’s pretend we’re sitting on top of Batian.’

Makena joined her reluctantly. ‘That takes a huge leap of imagination.’

‘That’s why I gave you my gift – to help you make it. Didn’t you say that all you had to do was touch your jar of melted snow and, in your mind, you’d be sitting on top of Mount Kenya?’

‘I did.’

‘Well, then?’

Makena couldn’t help laughing. She took the jam jar from her backpack, held it between her palms and closed her eyes. Blanking out Mathare Valley and the smell of rotting rubbish, she pictured herself sitting beside Lake Rutundu, breathing in the herby smell of heather. Snow glistened on Mount Kenya’s peaks. All around her was mauve-tinted moorland and eagles wheeled overhead.

A rowdy group of boys brought her crashing down to earth. They began searching through the heaps nearby.

Makena gave up on her vision but not on her ambition to some day fill her jar with snow. She nudged her friend. ‘You’re always telling everyone else to have a mission. What’s yours?’

A dreamy expression came over Snow’s face. ‘I want to dance on a stage and have my name in lights like Michaela DePrince.’

She dug in her skirt pocket and pulled out a page from a magazine. It had been folded so often it was ready to disintegrate, but Makena had no trouble making out a black ballerina in a brilliant pink tutu. She appeared to be flying – actually flying – over the red brick buildings in New York City.

‘That’s Michaela,’ Snow said proudly. ‘Isn’t she beautiful? She was a war orphan from Sierra Leone.’

‘A war orphan?’

‘Uh-huh. When she was four, this magazine picture of a ballerina dancing The Nutcracker blew into her orphanage. She made up her mind that one day she would dance and be happy like the girl in the picture. Her teacher was killed in front of her and so many bad things happened to her, but finally some kind Americans adopted her. Now she’s a dancer with the Dutch National Ballet and I’m looking at her photo and dreaming of being happy like her. After I read her story, Mama bought me a ballet book and I taught myself some moves. It’s a circle.’

Makena admired the picture. The young woman was so graceful and strong. ‘Have there been any albino dancers?’

‘Hundreds! There’ve been albino singers and actors and athletes too. Some are famous but those aren’t always the best. No one ever thinks about the nameless ones because they don’t sell expensive tickets, but a lot of them have done things that are far more important. They’ve helped people who are hurt or made war children smile. These are the legends in the real world – our world.’

‘But you still want to be on the stage with your name up in lights?’

‘Yes,’ Snow cried passionately. ‘Not because I want to be rich and famous, although that would be cool, of course! More because I want to inspire people the way Michaela has done.’

Makena decided right then that when she grew up she too wanted to inspire kids to be proud of who they were. She wasn’t sure how, but she’d think of a way.

Snow nudged her. ‘Read Michaela’s story out loud. Reading’s hard for me. The words go back-to-front and sideways. They dance, but not in a good way.’

‘You can get help for that,’ Makena told her. ‘Glasses or contact lenses.’

‘Here? In the slum?’

‘Maybe not here but when you’re a dancer on stage.’

‘Okay, I will. Now tell me what the story says.’

Halfway down the page Makena came to a quote from Michaela. ‘The corps is the backdrop to the story—’

Snow giggled. ‘It’s not corpse as in dead person. It’s “corr”, as in corps de ballet. It’s French. In the book my mama gave me, it said that’s the name for the ballet dancers who dance together as a group. The soloists, the principal dancers, are the ones who get all the attention, but the corps is like a family. They belong to each other.’

The page blurred before Makena’s eyes. She’d once belonged.

She struggled on: ‘Michaela says: “The corps is the backdrop to the story, a forest, a snowstorm, a flock of birds or a field of flowers. One red poppy in a field of yellow daffodils draws the audience’s eyes to the one poppy. However, I don’t think the answer is to cull the poppy. I think it’s to scatter more poppies about the field of daffodils.”’

Snow tucked the article into her pocket. ‘That’s what I’m going to do. I’ll be a red poppy scattering the seeds of hundreds more poppies.’