A coffee farm or a mistress?

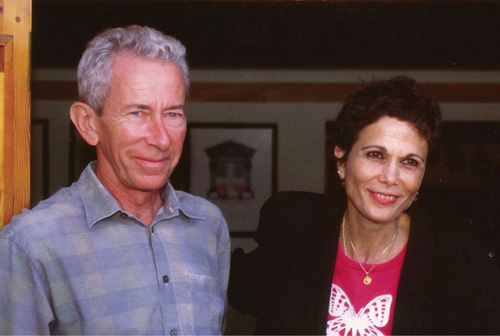

Over the years, Bill and I got to see a lot of Piti. Whenever we could get away from our lives and jobs in Vermont—short trips of a week, longer trips of a few weeks—we headed for the Dominican mountains. We had become coffee farmers.

Every time I get started on this story, the curtain rises on that vaudeville act that long-term couples fall into: who did what first and how did we get in this fix.

It began in 1997 with a writing assignment for the Nature Conservancy. I was asked to visit the Cordillera Central, the central mountain range that runs diagonally across the island, and write a story about anything that caught my interest. While there, Bill and I met a group of impoverished coffee farmers who were struggling to survive on their small plots. They asked if we would help them.

We both said of course we’d help. I meant help as in: I’d write a terrific article that would bring advocates to their cause. Bill meant help, as in roll-up-your-sleeves and really help. I should have seen it coming. Having grown up in rural Nebraska with firsthand experience of the disappearance of family farms, Bill has a soft spot in his heart for small farmers.

We ended up buying up deforested land and joining their efforts to grow coffee the traditional way, under shade trees, organically by default. (Who could afford pesticides?) We also agreed to help find a decent market for our pooled coffee under the name Alta Gracia, as we called our sixty, then a hundred, and then, at final count, two hundred and sixty acres of now reforested land. I keep saying “we,” but, of course, I mean the marital “we,” as in my stubborn beloved announces we are going to be coffee farmers in the Dominican Republic, and I say, “But, honey, how can we? We live in Vermont!”

Of course, I fell in with Don Honey, as the locals started calling Bill, when they kept hearing me calling him “honey, this,” “honey, that.” The jokey way I explained our decision to my baffled family and friends was that it was either a coffee farm or a mistress. Over the years, I admit, I’ve had moments when I wondered if a mistress might not have been easier.

We were naïve—yes, now the “we” includes both of us: We hired a series of bad farm managers. We left money in the wrong hands for payrolls never paid. One manager was a drunk who had a local mistress and used the payroll to pay everyone in her family, whether they worked on the farm or not. Another, a Seventh-Day Adventist, who we thought would be safe because he wouldn’t drink or steal or have a mistress, proved to be bossy and lazy. He was el capataz, he boasted to his underlings, the jefe, the foreman. He didn’t have to work. Every day turned out to be a sabbath for him. His hands should have been a tip-off, pink-palmed with buffed nails. Another manager left for New York on a visa I helped him get. (Like I said, it takes two fools to try to run a coffee farm from another country.)

Still, if given the choice, I would probably do it again. As I’ve told Bill many a time—and this gets me in trouble—even if in the end we’re going to be royally taken, I’d still rather put my check mark on the side of light. Otherwise, all the way to being proved right, I’d have turned into the kind of cynic who has opted for a smaller version of her life.

And things have slowly improved on the mountain. Over the years, the quality of the coffee being grown in the area has gotten better. Local farmers are being paid the Fair Trade price or higher, and the land is being farmed organically. We also started a school on our own farm after we discovered that none of our neighbors, adults or children, could read or write. It helps that I’m associated with a college, with ready access to a pool of young people eager to help. Every year, for a small stipend, a graduating senior signs on to be the volunteer teacher. Recently, we added a second volunteer to focus on community projects and help out with the literacy effort.

During the tenure of one of the better managers, Piti was hired to work on the farm. It happened while we were stateside, and when we arrived, what a wonderful surprise to find him at our door. “Soy de ustedes.” I am yours. “No, no, no,” we protested. We are the ones in your debt for coming to work at Alta Gracia.

Piti later told me how it had happened. His Haitian friend Pablo had found work on a farm belonging to some Americanos. (Because I’m white, married to a gringo, and living in Vermont, I’m considered American.) It was a good place: decent accommodations, reasonable hours, Fair Trade wages “even for Haitians.” Piti put two and two together. The chichigua lady and Don Honey. We were not in country at the time, so Piti applied to the foreman, who took one look at this runt of a guy and shook his head. Piti offered to work the day, and, if at the end, he hadn’t done as much clearing as the other fellows on the crew, he didn’t have to be paid.

Piti turned out to be such a good worker that he became a regular. His reputation spread. After several years at Alta Gracia, he was offered a job as a foreman at a farm down the road. Piti had become a capataz! One with calloused hands and cracked fingernails who could outwork any man, Haitian or Dominican.

He was also a lot of fun. Nights when we were on the farm, it was open house at our little casita. Whoever was around sat down to eat supper with us. Afterward came the entertainment. At some point, a visiting student taught Piti and Pablo to play the guitar, then gave it to them. A youth group left a second guitar. Bill and I bought a third. Then, like young people all over the world, Piti and Pablo and two other Haitian friends formed a band. Mostly they sang hymns for their evangelical church. Beautiful, plaintive gospel songs à la “Amazing Grace,” in which the down-and-out meet Jesus, and the rest is grace. We’d all sing along, and invariably, Bill and I would look at each other, teary-eyed, and smile.

And so, the curtain falls on the coffee-farm vaudeville act.

It was on one of those evenings that I promised Piti I’d be there on his wedding day. A far-off event, it seemed, since the boy was then only twenty, at most, and looked fifteen. One of those big-hearted promises you make that you never think you’ll be called on to deliver someday.