14

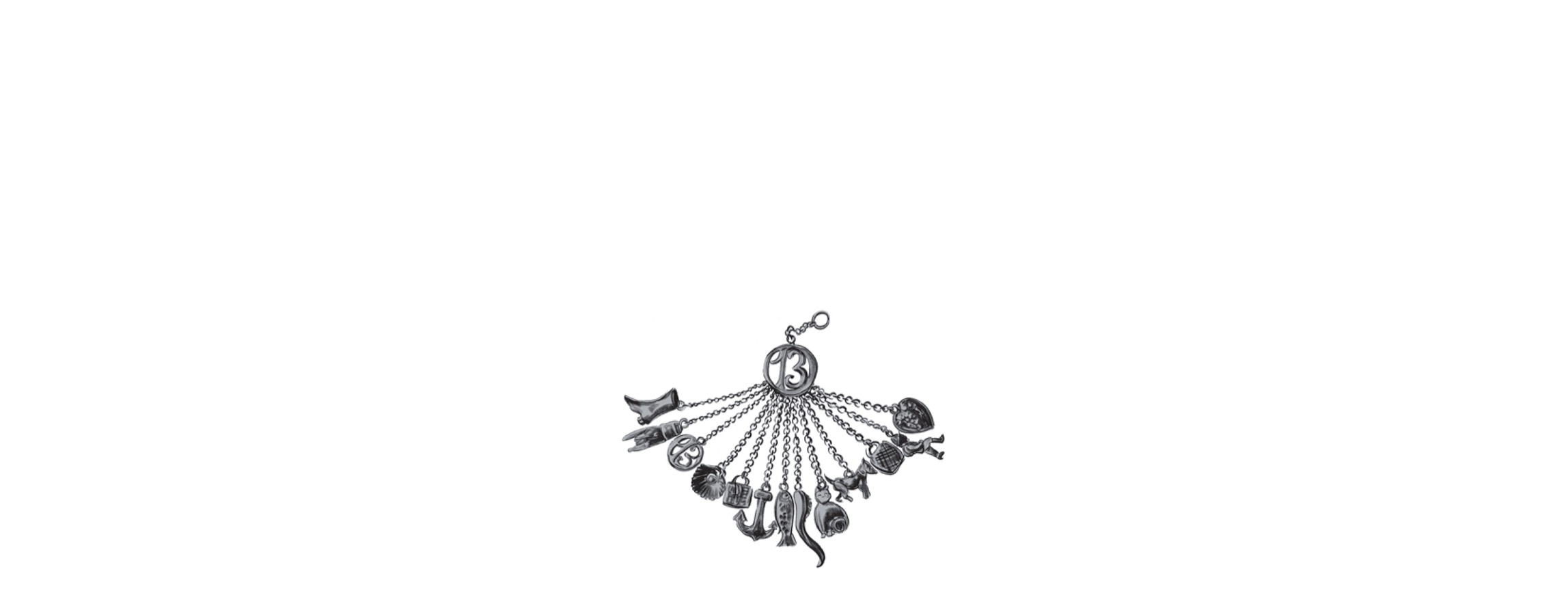

Chatelaine

THEY WOKE TO a furious pounding on the door.

“Up! Up!” Marie ran into the room. “The Lady will not tolerate a late supper! Up at once! I can’t be responsible for you at every turn. Oh, you should be in your uniforms. Now there’s no time. Just come down at once.” She tsked as she ran out again.

The back of Kat’s neck was slick with sweat as she tried to shake off the nightmare. Amelie rubbed her eyes fiercely, a rumpled mess in her twisted wool jumper.

“Come on, then,” Kat said. Her hands trembled.

“I don’t need to eat,” Ame said, grumpy. “Want to stay here.”

“We’ve got no choice.”

Kat tried combing out their hair—Amelie had terrible knots and cried out more than once, and Kat finally gave up, saying, “That will have to do.”

They rushed down the great stairs into the central hallway and turned left, and—“No! It’s right. Sorry, Ame”—Marie calling them along, so Kat followed the sound of her voice until they finally reached the dining hall.

Now fires roared in both fireplaces. Light streamed in from the high windows; the sun had come out from behind the clouds while they napped. The table was spread again for a feast. Everyone stood at their places at the table, including Peter and Rob and three other children, two boys and a girl. It was clear that they’d all been waiting for Kat and Amelie, and they glared at them as they stumbled in. Rob and Peter wore their uniforms, and Kat tried brushing her messy hair back from her face, feeling the blush of embarrassment.

At the head of the high table, raised above the table where the children waited, stood the Lady Eleanor, and standing next to her was a man. Kat thought he had to be Lord Craig, though he didn’t look ill in the least.

Kat dragged Amelie as fast as they could move until they stood before the Lady, and then Kat dropped into a curtsey; Amelie copied her, mumbling annoyance. “Sorry, my Lady,” Kat panted.

The Lady Eleanor lifted her chin. Her white-blonde hair was swept into a side chignon, and she was dressed to the nines. She wore the kind of gown that wouldn’t keep anyone warm unless they lived in the equatorial regions, where bare arms covered only by black above-elbow gloves would be a relief. Her dress was shimmery, full-length, body-hugging, although she wore an elaborate belt from which hung a Scottish sporran made of leather and a scarf in the Craig tartan. All the male eyes in the room were on the Lady. Kat would’ve liked to kick Peter in the shins. Robbie was almost drooling.

“You will dress in uniforms for every occasion,” the Lady said, her voice cold even as she gave them a thin smile. “We eat before sunset here. You will not be late again.”

“No, ma’am.” She curtseyed again, this time to the man. “Good evening, my Lord.”

At that, the man burst into mocking laughter.

Kat stiffened, first at the sound of that laugh, and then at the looks she—and the man—received from the Lady.

“‘My Lord’!” the man said, sputtering with laughter. “She called me ‘my Lord’!”

“Yes, well, she is an ignorant girl,” the Lady said, loud enough for Kat to hear.

Kat’s hand tightened on Amelie’s.

“You can call me Sir,” the man said with a narrow-eyed grin, “but I’m no proper lord.”

The Lady turned cold eyes on Kat. “This is not my lord husband,” she said. Her teeth gleamed in a smile that didn’t reach her eyes. “This is Mr. Storm, one of your instructors. Now that you’ve all arrived, and the other teachers arrive tomorrow, lessons shall begin.”

“About bloody time for something interesting to begin,” murmured the boy standing a few feet behind Kat. “Been a bloody bore here so far. That bugger had us locked in study hall all day, he did, while he was off someplace.”

That “bugger” Mr. Storm held the Lady’s chair for her and swept his hand for her to sit, and the Lady gave him a look that would freeze a polar bear, though he either didn’t see or didn’t care. When he pulled his chair out to sit, Kat heard the scraping of the chairs behind her and she tugged Amelie to the two empty places at the table, while stealing another look at Mr. Storm.

Instructors come in all shapes and sizes, but Mr. Storm didn’t fit Kat’s idea of an instructor. To be honest, he hadn’t fit her idea of a lord, either. He was built square, and wore an ill-fitting tweedy jacket that seemed too small for him, and he had a flat haircut that left his blond sprigs shooting skyward. He still shook with laughter like a heaving barrel, and Kat thought that, really, her comment wasn’t all that funny. It was as if he was privy to some secret joke.

The Lady, bristling, motioned for them to eat.

Although it had been but a few hours since lunch, a feast was laid before them yet again. Mutton, potatoes, beets. Kat rubbed her forehead, still groggy from her nap and unnerved by her nightmare, trying to balance the coldness of the Lady with the comforts of the food and the castle.

The others at the table made introductions. The rude boy was Jorry Phillips, who was from Belgravia, the swankiest of London’s neighborhoods. Jorry was as thin as a rail, with a long nose and a sour expression and a red smear of birthmark that emerged from the collar of his shirt.

“Don’t much care for all this meat,” Jorry said. “Mother’s raised me as a vegetarian, and to be fit and healthy. But without a balanced meal I have to eat this. It’s probably going to make me sick. Plus we’re not allowed to be outside without permission, so there’s nothing to do here but sit about, no calisthenics or other vigorous exercise. I’ve been doing push-ups in my room, but it’s hardly enough, you know. We’ll all be fat as hogs soon, eating like this. That Mr. Storm isn’t much of an instructor, if you ask me. Claims his field is history.”

Kat was glad to be a couple of places removed from Jorry.

She was seated on one side next to the younger of the two boys, Colin Drake. Colin was sweet and eager, chattering away about anything that crossed his mind. Kat thought he and Robbie, close in age, would make a fine pair of bookends, and indeed, they seemed to be striking up a friendship, talking about the armor and fencing and castle living.

She turned to the girl on her other side. “Isabelle LaRoche,” the girl said, with the faintest accent. “You’ve come up from London, yes? My mother’s English and Papa’s French, and we were in Paris until last spring. Papa got us all out ahead of it.” Kat knew Isabelle meant the German incursion into France. “Heureusement, I was able to bring my clothes from Paris. This uniform is so dull.” Isabelle smoothed the collar of her white shirt—it looked as if she’d starched it—and raised one eyebrow as she surveyed Kat’s outfit.

Kat plucked at her wrinkled jersey.

Amelie, on Isabelle’s other side, said, “I think the uniform looks well on you.”

Isabelle preened a bit. “Merci. You may be about my size, since I am small for my age. When we’re not in uniform we can play dress-up. We’ll try things from my closet. Yes?”

Kat brushed at her jersey again and picked at her food.

Isabelle leaned over to Kat, whispering. “The Lady, she is glamorous and has beautiful clothes.”

Beautiful, but odd. Kat glanced at the Lady, whose chignon swept artfully over one ear. “She does.”

“But I must tell you, something’s peculiar in this academy.”

“Why do you say that?”

“I saw something, when we first arrived. It was very strange.” Isabelle dropped her voice further.

“What was it?”

“A boy. I watch from the window when no one is around.” Isabelle shrugged. “He is good-looking, you know? Anyway, he is feeding les chats. But I watch the boy, and I realize that his eyes, they do not really see. He is like a ghost. And as I watch, well, I glance away for just a moment and then . . . poof!” Isabelle snapped her fingers.

“Poof?” Kat echoed. A chill crept over her despite the fires raging in the fireplaces. “You mean he disappeared?”

“Mais oui. I only look away for an instant, and I could not see him after.”

Like the girl by the pond. “His eyes—was he blind?”

But Isabelle shook her head. “Non, non, nothing like that. Something else.” She leaned closer to Kat and dropped her voice. “He is standing, frozen, before he vanishes. His eyes are all wide and . . . nothing.” Isabelle pointed to her own blue eyes, now round and staring. “Like this.” She waved her fingers. “Marie says he is ill, but that is not how it looked to me. Unless he is ill in the head.”

“Marie knew about him?”

“Of course,” Isabelle said, pouting a little. “When I see him wandering about, looking enchanté . . . how do you say? Enchanted. I watch for him. And I see him again, once more. He feeds his cats, but he is again looking enchanté.”

Kat shifted. “Did Marie say anything more? Does he live in the castle?”

Isabelle shrugged and ate a delicate bite of food. “Somewhere with his cats. I haven’t seen him since the second time.” Then she leaned toward Kat, one long curl of her hair sweeping forward over her shoulder. “He wears a long necklace. I see it as he bends to his cats. I have very good eyes.”

“A necklace.”

“Yes, an odd thing. A necklace with a charm at the end. The charm is shaped like a cat.” Isabelle hesitated. “It reminds me, a little, of the charms on the Lady’s belt.”

Kat sat straighter. “The ones she wears on her chatelaine?”

“Ah, you know some French? You know of la châtelaine?” Isabelle seemed excited. “Oui, les charmes sur sa châtelaine. The Lady hides this chatelaine she wears. Once when she does not realize I can see it, I catch a glimpse of one charm.” Isabelle leaned even closer so that only Kat could hear. The boys were devouring their dinner, all four now chattering loudly about football. “That charm was”—Isabelle dropped her voice to the lowest of whispers—“the sign of evil.”

The room darkened with sunset just as Isabelle said the word evil. The only light in the hall came from the fireplaces, a dull red glow. A chill like tiny feet crawled up Kat’s spine now, bringing up goose bumps all over.

“Sign of evil?” she whispered back.

“Like this.” Under the table Isabelle made the familiar hand sign for the warding off of evil things, the horns—les cornes—of the devil.

Kat shuddered. “Are you sure?”

Isabelle nodded, solemn. “Mais oui.” She picked at her food. “I am thinking the Lady wears this charm to ward off bad things. But the handsome boy, he found bad things even so, of that I’m sure.”

Isabelle’s eyes dropped away. Her dark hair formed perfect ringlets. She didn’t seem the practical sort; no one would call her stodgy. Maybe she even liked to tell scary stories. Maybe she shared Amelie’s imaginative streak.

So the boy with the cats wore a necklace charm in the shape of a cat and seemed enchanted. Two other ghostly children wandered about the castle as if lost. And the Lady wore on her chatelaine the sign to ward off evil. Why would the Lady wear such a thing?

Unless there was something evil in this castle, and she wore it for her own protection. Perhaps the ghost of the Lady Leonore did wander the castle, with an evil purpose.

Kat shook herself. What was wrong with her? There must be a logical explanation for everything. Of course. It was just a matter of picking things apart, like opening the back of a clock and taking out the mechanism bit by bit to discover how all the pieces fit together.

“My Lady?” Kat said, standing up and lifting her voice to be heard above the chatter.

Everyone froze. The Lady, sitting straight up in her chair at the head table, appeared to have eaten nothing, her hands flat on the table before her. She stared down at Kat, one eyebrow lifted. “Yes?”

“Where are the others?” The blood rushed into Kat’s cheeks, and she thrust her trembling hands behind her back.

“The other . . . ?”

“The other children. We saw them, earlier today. A girl wearing a gauzy frock out in the cold garden, and a crippled boy. And . . .” Isabelle nudged Kat hard in the thigh, so she stopped herself from saying something about the cat-boy. “Why aren’t they at supper?”

The fire popped and snapped in the silence. Mr. Storm stopped chewing and stared. “Other children?” he mumbled.

The Lady braced her hands on the table and then stood. “I’m afraid I must leave you. It’s time for me to tend to my husband. Please, finish your supper under the watchful eye of Mr. Storm.” She gave Mr. Storm a swift glance, then glared at Kat. “In the future, you will refrain from addressing the upper table.”

The Lady left the hall.

Every male eye in the place followed her sweeping form. Robbie, Kat understood. But she admitted to being disappointed in Peter. And disappointed in herself for caring what he thought.

After the great doors closed behind the Lady with a thud, they ate in silence, the boys’ chatter dropping away so it was quiet all around. Even Mr. Storm was silent, although he made loud unpleasant noises as he chewed his food and heaped his plate.

Marie came in with hot chocolate, and Kat wondered at such extravagance, having cocoa in the midst of war, and remembered that the Lady said she’d stockpiled sweets. But she must have had some foresight, since even Kat’s own parents hadn’t guessed the war would last so long. The children each drank two full cups, even Kat, while Mr. Storm helped himself to several glasses of claret.

The fires burned lower and lower and the room grew dim, and Kat found herself nodding in her chair, even as they drank their chocolate. The next she knew, Mr. Storm was gone, the fires had smoldered to ashes, the room was thick in shadow, and they all sat as if in a stupor. Kat couldn’t tell how much time had passed.

Peter stood up. “Got to get to sleep,” he mumbled. “Must be the long trip, but I’m beat.”

They left the hall as a group, the half-eaten meal remaining on the table, with no sign now of Marie nor Cook, and somehow they found their way to the stairs, dragging themselves up to their rooms. Kat held Amelie’s hand as much for herself as to keep Ame moving. As they passed the portrait in the hall Kat could have sworn the blue eyes of the Lady Leonore followed her.

Isabelle, Jorry, and Colin had rooms down the hall from Kat and Ame, but they were barely able to murmur good nights before falling into their chambers.

Kat must have washed and changed and helped Amelie wash and change, but she didn’t remember a thing about it later. At some point she heard the lock on the door snap shut from outside.

Trapped, was her last waking thought.