There was no way in which the Melendy children could go to school until Mrs. Oliphant’s station wagon arrived. The Carthage public school was three miles away, and though Rush liked to picture himself swinging along the country road in the morning like Abraham Lincoln, the thought of returning by the same lengthy route had less glamour. Willy’s friend, Mr. Purvis, the garbage collector, said he’d be glad to take two of the children to town each morning, but there’d be no room for the other two except in back with the garbage. Oliver couldn’t see why this wasn’t a practical arrangement. Still they hadn’t so long to wait. They had arrived on Friday evening, and the station wagon was due to appear on the following Thursday.

In the interval they unpacked, and explored, and had picnics every day in a different place. Their range seemed almost unlimited, for there were thirty acres of land that went with the house, and a sample of everything delightful, short of an active volcano and an ocean, that one could want on his own territory: brook, woods, stable, hollow tree, and summerhouse. Each of the children had found something that belonged particularly to him by right of discovery. Rush had found the brook, of course, and Mona discovered the orchard: it was full of warped old trees covered with suckers, and the apples that had fallen in the grass tasted half wild and bitter sweet. Randy found a little cave, and a swampy place where fringed gentians were in blossom, but her important discovery was to come later.

Oliver found the cellar.

Of course they all knew that there was a cellar but nobody, except Willy, had ever been down to look at it, and even he had looked at nothing but the furnace. It remained for Oliver, on the third day, to open an inconspicuous door off the kitchen and find the dusty stone steps going downward into darkness. A rank, delicious smell of cold stone and damp filled Oliver’s nostrils. Prudently and quietly he closed the door; this was to be his own personal voyage of discovery, and no one was going to be allowed to assist or interfere.

He tiptoed up the back stairs to borrow Rush’s flashlight, without mentioning his intention to Rush who was conveniently practicing in the Office. Then he tiptoed down again, through the kitchen, and past Cuffy’s broad, preoccupied back at the stove. Once again he opened the inconspicuous door, stepped in, and closed it quietly behind him. The flashlight led him down the steps by its circle of light.

The floor of the cellar was concrete, and its walls were the stone foundations of the house. The air of the place was dank and still, like the air of a medieval dungeon; Oliver breathed it deeply. Overhead dangled a fixture with no bulb in it, but he saw that there were windows, small windows flush with the ceiling. They glowed with a filtered, greenish light, being almost entirely smothered by grass stems, weeds, and clinging tentacles of Virginia creeper. He switched off the flashlight, enjoying the mysterious gloom. A second later he switched it on again, his heart pounding in his chest, and saw that what he had taken in the dimness to be an indescribable monster was nothing but a large coal furnace. Something like the one at home only bigger and more complicated, with great brawny pipes and tubes, and a grate in its lower door that looked like teeth in an iron mouth.

“Hello, furnace,” Oliver said placatingly. He opened the door with the grate and stuck his head in, and sniffed the smell of dead ashes. He turned the flashlight into it, too, but saw nothing except some very old cinders, so he closed the door and went on with his exploring. The only other things in the furnace room were a stack of dry logs that crackled from time to time as though full of mice, and a bin with coal in it. Oliver went into the bin and climbed up and down the slipping mountain of coal; he fell once or twice but that only added to his pleasure and the damage of his clothes. He pretended he was climbing a crater in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. At the end of fifteen minutes, when he emerged, he was black as a Cardiff coal miner and extremely happy.

From the furnace room two other chambers opened out. In the first one Oliver found an old bedspring, an empty barrel, and a Mason jar high up on the windowsill containing nothing but a large, hairy spider which he did not disturb. The spider’s web was laced across the window, and was hung with dried fragments of moth wings, and the husks of beetles and houseflies.

The second room had a wooden door which was shut. Oliver had a hard time getting it open: it was stuck in its casing as though it had not been opened for a very long time. But he pushed against it with all his weight and finally it flew open and he flew into the room with it.

He could hardly believe his eyes.

This room was smaller than the other, and it was to Oliver as the cave was to Ali Baba: a storehouse full of treasure.

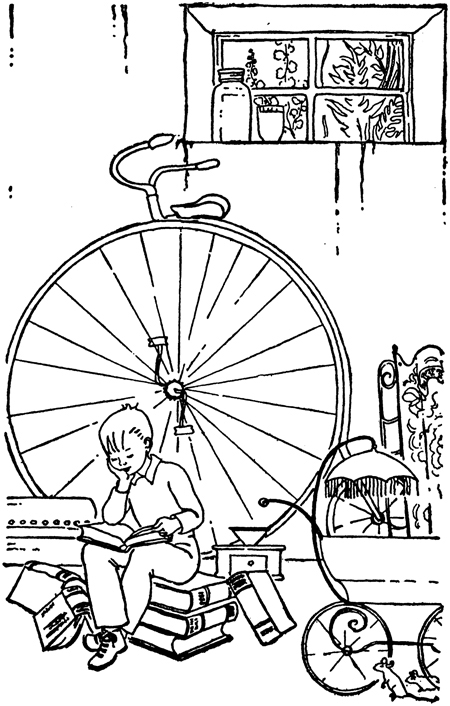

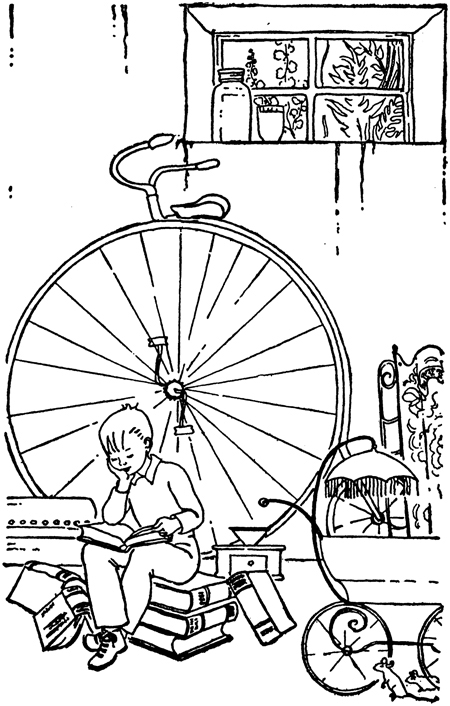

The first things he saw were two sleds propped up against the wall on their hind legs. They were very old, with rusted runners, and one was red, and one was blue. Names were painted on them in fancy letters. “Snow Demon,” said one; and “Little Kriss Kringle,” said the other. They must have belonged to the Cassidy children, thought Oliver. And then he saw the bicycle. Upstairs in the attic there were pictures of boys riding bicycles like this one. The front wheel was taller than he was, though the back wheel was small; and the saddle and handlebars soared loftily atop the front wheel. If only my legs were longer, thought Oliver impatiently, looking down at his short, fat underpinnings; this bike is much better than the kind they have nowadays; more dangerous.

Besides the bicycle and the sleds, there was an old-fashioned tin bathtub covered with rust and chipped paint of robin’s-egg blue, and shaped like an armchair with a high back. And there were more Mason jars, with more spiders in them, and a doll carriage made of decaying leather, and a broken coffee grinder, and a cast-iron crib frame, and a set of big books. All the objects in the room were covered with a layer of fine, ashy, white dust. Oliver sat down on one of the books, took another on his lap, reveling in the dust, and began to look at it. It turned out to be the bound volume of a magazine called Harper’s Young People, published in the year 1887. The book was mildewed, some of its pages were glued together by years of damp, and its green cover had been gnawed by mice, but it exuded the indescribably delicious odor of all ancient books; better still, it was full of the pictures and adventures of the children of that other world which he had already explored on the walls of the Office upstairs. A world where girls wore sashes and long hair, and boys wore long stockings and button boots, and the horses which pulled the trolley cars wore straw hats. In that world there were no automobiles, no airplanes, no streamline trains, and yet the children seemed to be almost the same kind of children there were now.

Overhead Cuffy’s feet creaked to and fro across the kitchen floor boards. Outside the morning was clear and golden with Indian summer. But Oliver sat in the dim light of his cellar room; pale and happy as a mushroom in its native habitat.

Hours later his reluctant ear was pierced by the frantically repeated sound of his name. “Oliv-er! Oliv-er!” cried Cuffy, faint and faraway. He heard her feet hurry across the kitchen floor; the screen door open. “Oliver, come in for your lunch!” called Cuffy. He sat listening and when he heard her feet go out of the kitchen he rose, closed the door of the marvelous room behind him, and ran silently up the steps.

When Cuffy returned to the kitchen she found Oliver there, gazing dreamily out the window.

“Great day in the morning!” she said exasperatingly. “Where in the world have you been? And how in the world did you get so dirty?”

Oliver neatly evaded this question by answering it with one of his own. “Am I dirty, Cuffy?” he asked, looking surprised.

“I never saw such dirt. Dirt all over you, and something that looks like coal dust; and what have you got dangling from your ear? I believe it’s a cobweb. Come here while I wash you.”

All through lunch Oliver ate without knowing that he ate at all. A baked potato, two slices of liver, and a large helping of beets (which he detested) simply disappeared from his plate into himself without conscious material assistance on his part. Inwardly he had entered once more the little room that was his discovery, his kingdom. He dwelt longingly upon the thought of the two old sleds, the bicycle, the coffee grinder (which he planned to take apart), and above all the books. Tomorrow I’ll go down again, he told himself, and whenever it rains, and when Cuffy takes a nap. But I mustn’t go too often. Oliver was wise for his seven years: already he knew that to overdo a thing is to destroy it. I’ll keep it secret for a long, long time, he thought. He did, too; for he had great determination, and knew the secret of keeping secrets.

Also he had a kind heart. Six weeks later when Randy had to stay home from school with a toothache he took her down to the cellar and showed her his discovery. It worked better than oil of cloves: Randy forgot her toothache for more than an hour and a half, absorbed in the dusty volumes of Harper’s Young People.

Afterward she and Oliver referred to the secret cellar room by its initials S.C.R. They referred to it ostentatiously and often, much to the outward boredom and inward consuming curiosity of both Mona and Rush, who were not enlightened until the twenty-fifth of December when Oliver showed it to them for a Christmas present.