“This Christmas,” Father said to them, “there is war; and I am poorer. You’ll have to do a lot for yourselves. You’ll have presents, of course, but perhaps not such fine ones as before. Try to remember how lucky we are. A family living together in a nice funny old house: a family that’s fortunate enough to have light, and food, and warmth, and no fear of anything.”

“That’s quite a lot,” Rush said afterward. “I’ve been reading the papers and I know that that’s quite a lot for us to have.”

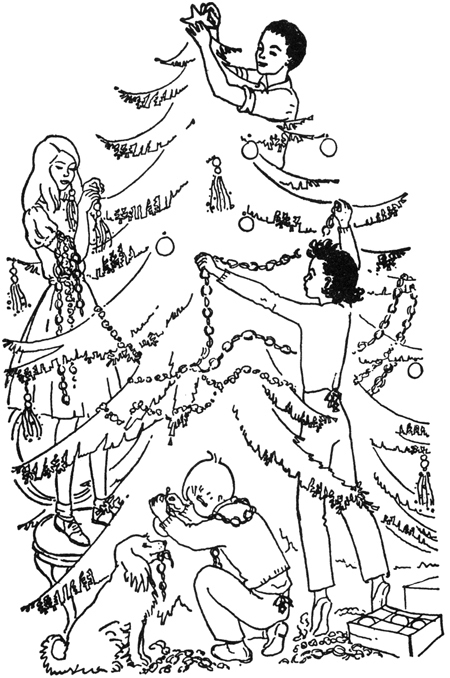

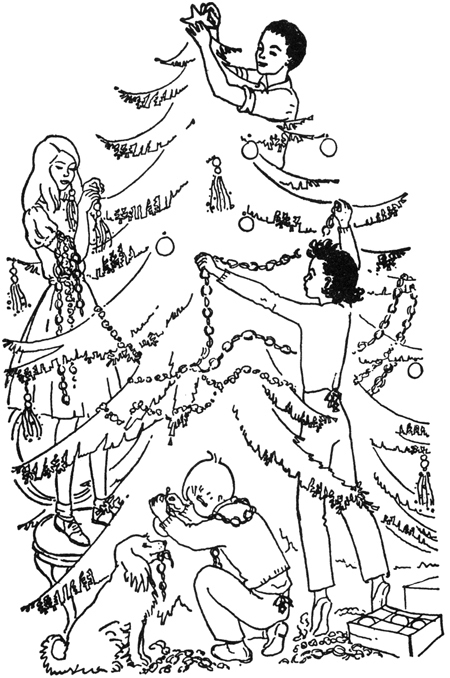

So this year they made Christmas for themselves. And it was fun. More fun, really, than buying things ready-made. Willy and Rush investigated the woods and returned with a Christmas tree and a Yule log. With much prickling and ouching Randy and Mona made wreaths for the windows out of wild ground pine, evergreen, and holly. The old, scarred Christmas tree baubles were resurrected from their box, and in addition Oliver strung popcorn chains, and made many paste-blurred link chains of gold and silver paper; and there were bright woolen tassels of Mona’s devising, sewn with Mrs. Oliphant’s sparkling sequins. The tree was beautiful when it was trimmed: the handsomest tree they’d ever had, the Melendys thought.

Christmas looked promising in spite of what Father had said. An enormous box had arrived from Mrs. Oliphant; and Oliver happened to know that there were other mysterious boxes on the top shelf of the linen closet. Cuffy spent the day before Christmas locked in the kitchen; nobody was even allowed to look in at the windows. A dazzling fragrance breathed itself through the crack under the door, and filled the whole house with frankincense and myrrh.

This year the children had made most of their presents. Mona had knitted scarves for everyone out of the most brilliant colors she could find; they were like woolen rainbows. Randy had made a big sachet for Mona, and another for Mrs. Oliphant; a pincushion (stuffed with milkweed) for Cuffy; a blotter holder for Father’s desk; and for Oliver she’d filled a scrapbook with cutout pictures of planes, battleships, submarines, and tanks. For Rush she had saved enough out of her allowances to buy a record he’d wanted for a long time: boys are so hard to make things for, and she wanted to give him something he’d really like.

Rush had composed a piece of music for everyone. A sonata for Father, called “Opus I.” A sonata for Mrs. Oliphant, called “Opus II.” The rest of them had regular names: Cuffy’s was called “Music to Cook By”; Mona’s was “Incidental Music for Macbeth”; Randy’s was “Funeral March in F” (she loved funeral marches); and Oliver’s was a “Military March” which he didn’t appreciate. To Willy, who had often displayed a wistful interest in music, Rush gave a recorder and some easy tunes to play on it. Thereafter mournful tootlings could be heard coming faintly from the stable at odd hours of the day or night when Willy wasn’t working.

Oliver made thick, wobbly, clay ashtrays for everyone, though nobody smoked except Father. “They can use ’em for pins and elastic bands and things,” Oliver told himself comfortably.

To compensate for the humbleness of their gifts they took great pains with the wrappings. Especially Mona, who spent literally days rustling and crackling about among crepe and tissue papers, and was always trailing bits of string and red ribbon.

“Sh-h-h,” Rush said to Randy. “Don’t tell anybody, but I think she’s building a nest.”

On Christmas Eve they sang carols, all standing around the piano in the living room. The tree glittered dimly in its shadowed corner: it was asleep, waiting; and under its protecting boughs it hid a rich harvest of unopened presents. Oliver’s sock hung empty from the mantel (the rest of them had given up stockings this Christmas) and the Yule log in the fireplace was waiting for tomorrow, too.

They sang “God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen” and “Silent Night” and “Adeste Fideles” and “Oh, Little Town of Bethlehem” and “Noël, Noël” and lots of others. Randy’s favorite was “We Three Kings of Orient Are.” As she sang its minor air she could almost see the three kings riding on three tall camels: their glorious robes and glorious gifts all silvered and dazzling under the light of the Star.

“Look!” cried Mona, when they had finished. “It’s snowing!”

How perfect! Snow on Christmas Eve. Please, please, let it last until tomorrow!

When she was ready for bed Randy leaned out the window. Far out, so that she could feel the little cold sharp flakes against her cheek. They glittered like tinsel in the light from the window. She could hear the brook murmuring under the ice, and the spruce branches sighing and sighing under the snow.

“Si-ilent night,

Ho-oly night,”

Randy sang in an exalted voice: and Cuffy pulled her in by the back of her pajamas.

“You want to catch your death? Pile into bed now, it’s almost nine.”

Randy threw her arms around Cuffy’s neck. “Oh, I love Christmas Eve!” she cried. “Even better than Christmas I love it. Because everything’s just about to happen!”

“Influenza’s about to happen if you don’t get into bed with them windows open,” growled Cuffy, giving her a kiss and a shove both at once.

Randy went to bed but not to sleep. For a long time she lay listening to the cold whisper of the snow. “Christmas, Christmas, Christmas,” it was saying. She couldn’t help wishing that she believed in Santa Claus again. On such a night as this one could almost hear sleigh bells in the sky.

It had just got over being dark when she woke up: the morning was still new and unspoiled, like a pool into which no one has thrown a pebble. The first thing she saw was a big white cuff of snow on the windowsill. She got up and looked out. The floor was ice under her bare soles but she preferred the discomfort to the boredom of putting on bedroom slippers; she gathered a handful of snow from the sill and stood there licking it thoughtfully and looking out the window at Christmas Day. A few flakes still fell, but whether from the sky or from lightly moving branches it was hard to tell. The trees stood up out of the whiteness, black as ebony, and fine as lace. It was like the snow and trees that a man named Peter Breughel used to paint. Mrs. Oliphant had a book full of his pictures. At the thought of Mrs. Oliphant she remembered the mysterious box downstairs; she remembered Christmas and the presents, and was very happy.

But, oh, it was cold! All of a sudden a shiver crawled over her, beginning under her insteps and traveling right up over her scalp. Randy banged the window shut and leaped into her warm bed. She didn’t stay there long, though. Soon she was up again, and properly robed and slippered, opened the door into the hall. The house was warm and still. I am the only one awake, thought Randy.

Or was she?

There was a faint chink, and a shuffle, and the next thing she saw was Oliver coming slowly up the stairs in his bare feet, exploring a bulging sock as he came. His hair was standing straight up on one side like the feathers of a young thrush.

“Merry Christmas,” whispered Randy. “Where are your slippers?”

“Merry Christmas,” replied Oliver. “I don’t need them.

“Look, Randy, I’ve got a flashlight,” he said. “A pocket one, and two little tanks, and there’s something here that feels like a hand grenade.” But it turned out to be a baseball.

For breakfast that morning they had waffles and country sausage, and hot chocolate with big lumps of whipped cream on top, just like restaurant hot chocolate. Afterward Rush went into the living room and played the Mendelssohn Wedding March, because it was the first thing he thought of, and Father threw open the doors, and there was the lighted Christmas tree, come into its own at last: a shimmering mirage, a tree of Paradise, a pyramid of jewels.

Father distributed the presents. Papers flew, strings were tossed aside. Oliver grew white and strained with excitement: probably he would be sick at his stomach when this was over.

All the presents were successful. Cuffy had made taffy apples, and boxes of fudge, and gingerbread men for everyone. She even had a beef bone all done up in tissue paper for Isaac. Father’s present was swell new books: lots of books, and all the kinds they liked best. In addition he gave Rush a book of records: the Mozart Piano Concerto in C minor. Mona got the musical powder box she had craved for so long; Randy, a whole stack of drawing paper, and a really super paintbox; Oliver, a Meccano set; and Isaac, a new red collar with his name on it.

“I thought you said we weren’t going to have such good presents this year!” said Rush, looking accusingly at Father.

“I’m glad if you like them. But just wait till you see what Mrs. O has sent!” Father replied.

Her box was the last one. Mona cut the string, Randy pulled off the paper, Rush pried open the lid, and Oliver dived in. Inside there were four pairs of ice skates! Ice skates with shoes attached to them; just the right size for each child. “Oh, boy!” said Rush and Oliver. “Gee whiz!” said Randy. “How absolutely divine!” said Mona.

Besides the skates there was a new, a brand, glistening-new typewriter for Father, a quilted bathrobe for Cuffy, a big warm sweater for Willy, and a little warm sweater for Isaac!

And just as they were beginning to settle down, and had all the strings and ribbons curled up in a box and all the paper folded into a neat pile for Randy’s paper salvage, the front doorbell rang! When they got to the door they were just in time to see the back of a pickup truck vanishing over the hill.

“Now, who do you suppose—what’s that?” cried Cuffy, looking down.

There was a long coffin-shaped box on the front doorstep, with perforations in the lid.

“Maybe somebody’s left a baby for us to take care of,” said Randy hopefully. “See, there’s a card under that red ribbon bow on the top.” They looked at the card. It said:

Merry Christmas Folks

from

Mr. and Mrs. Ed J. Wheelwright

P.S. Handle with care, especially when opening

They were very careful: the same suspicion was forming in every mind. And it turned out to be correct. For when they removed the lid, there, nestled in a burlap sack, was Crusty Wheelwright the alligator, smiling his dreamy and hypocritical smile.

Father just said “Well!” and leaned against the door-jamb for support. Oliver and Rush and Willy were delighted. Randy was pleased in a dubious sort of way, Mona shrank back with an affected little squeal, and Cuffy said (and repeated it several times a day for the next week or so), “My lands! Some people sure know how to pass the buck!” She was quite cross, too, when Oliver said, “Oh, boy, hip, hip, hooray! Now we can keep him in our bathtub!”

Needless to say, this did not transpire. In a day or two Willy got a tank built for Crusty which they kept in the furnace room. But in the meanwhile his abode was a laundry tub in the kitchen. It was an uneasy period for Cuffy.

“Some Christmas,” remarked Rush in a satisfied tone at the end of the day. He was playing Randy’s Funeral March for her, very quietly in the dusk. “I bet we’re just about the only kids in the county, maybe even the whole state, that got such a big live alligator for a Christmas present.”

“Or maybe the whole country, or maybe an alligator at all,” agreed Randy, nodding her head slowly. “Yes. You know, Rush, it’s funny, but we always did seem to be luckier than most of the people we know.”