5

ALTERED STATES

Myths about Consciousness

Myth #19 Hypnosis Is a Unique “Trance” State that Differs in Kind from Wakefulness

As you sink deeper and deeper into your chair, the hypnotist drones, “Your hand is getting lighter, lighter, it’s rising, rising by itself, lifting off the resting surface.” You notice that your hand lifts slowly, in herky-jerky movements, in sync with his suggestions. Two more hypnotic suggestions follow: one for numbness in your hand, after which you’re insensitive to painful stimulation, and another to hallucinate a kitten on your lap. The cat seems so real you want to pet it. What’s going on? What you’ve experienced seems so extraordinary that it’s easy to conclude that you must have been in a trance. Were you?

The notion that a trance or special state of consciousness is central to the striking effects of hypnosis traces its origins to the earliest attempts to understand hypnotic phenomena. If you associate the term “mesmerized” with hypnosis, it’s because Viennese physician Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815) provided early and compelling demonstrations of the power of suggestion to treat people who displayed physical symptoms, like paralyses, that actually stemmed from psychological factors. Mesmer believed an invisible magnetic fluid filled the universe and triggered psychological nervous illnesses when it became imbalanced. Mesmer may have been the model for the magician of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice in the 1940 Walt Disney movie Fantasia. Dressed in a flowing cape, Mesmer merely had to touch his suggestible patients with a magnetic wand for them to experience wild laughter, crying, shrieking, and thrashing about followed by a stupor, a condition known as the “crisis.” The crisis became the hallmark of mesmerism, and Mesmer’s followers believed it was responsible for his dramatic cures.

Mesmer’s theory was debunked in 1784 by a commission headed by the then American ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin (by that time, Mesmer had decided to leave Vienna following a botched attempt to treat a blind musician and had moved to Paris). The investigators concluded that the effects of mesmerism were due to imagination and belief, or what today we would call the placebo effect—improvement resulting from the mere expectation of improvement (see Introduction, p. 14). Still, die-hard believers continued to claim that magnetism endowed people with supernatural powers, including the ability to see without their eyes and detect disease by seeing through their skin. Before doctors developed anesthetics in the 1840s, claims that doctors could use mesmerism to perform painless surgeries were fueled by James Esdaile’s reports of successful surgical procedures in India performed using mesmerism alone (Chaves, 2000). By the mid 19th century, many far-fetched claims about hypnosis were greeted with widespread scientific skepticism. Even so, they contributed to the popular mystique of hypnosis.

The Marquis de Puysugaur discovered what later came to be regarded as a hypnotic trance. His patients didn’t know they were supposed to respond to his inductions by going into a crisis, so they didn’t. Instead, one of his patients, Victor Race, appeared to enter a sleep-like state when magnetized. His behavior in this state seemed remarkable, and as hypnotists became more interested in what they called “artificial somnambulism” (“somnambulism” means sleepwalking), the convulsive crisis gradually disappeared.

By the late 1800s, myths about hypnosis abounded, including the idea that hypnotized people enter a sleep-like state in which they forgo their willpower, are oblivious to their surroundings, and forget what happened afterwards (Laurence & Perry, 1988). The fact that the Greek prefix “hypno” means sleep probably helped to foster these misunderstandings. These misconceptions were widely popularized in George Du Maurier’s novel Trilby (1894) in which Svengali, whose name today connotes a ruthless manipulator, uses hypnosis to dominate an unfortunate girl, Trilby. By placing Trilby in a hypnotic trance against her will, Svengali created an alternate personality (see also Myth #39) in which she performed as an operatic singer, allowing him to enjoy a life of luxury. Fast-forwarding to recent times, many of the same themes play to dramatic effect in popular movies and books that portray the hypnotic trance state as so powerful that otherwise normal subjects will (a) commit an assassination (The Manchurian Candidate); (b) commit suicide (The Garden Murders); (c) disfigure themselves with scalding water (The Hypnotic Eye); (d) assist in blackmail (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service); (e) perceive only a person’s internal beauty (Shallow Hal); (f) steal (Curse of the Jade Scorpion); and our favorite, (g) fall victim to brainwashing by alien preachers who use messages embedded in sermons (Invasion of the Space Preachers).

Recent survey data (Green, Page, Rasekhy, Johnson, & Bernhardt, 2006) show that public opinion resonates with media portrayals of hypnosis. Specifically, 77% of college students endorsed the statement that “hypnosis is an altered state of consciousness, quite different from normal waking consciousness,” and 44% agreed that “A deeply hypnotized person is robot-like and goes along automatically with whatever the hypnotist suggests.”

But research refutes these widely accepted beliefs. Hypnotized people are by no means mindless automatons. They can resist and even oppose hypnotic suggestions (see Lynn, Rhue, & Weekes, 1990), and they won’t do things during or after hypnosis that are out of character, like harming people they dislike. So, Hollywood thrillers aside, hypnosis can’t turn a mild-mannered person into a cold-blooded murderer. In addition, hypnosis bears no more than a superficial resemblance to sleep, because EEG (brain wave) studies reveal that hypnotized people are wide awake. What’s more, individuals can be just as responsive to suggestions administered while they’re alert and exercising on a stationary bicycle as they are following suggestions for sleep and relaxation (Banyai, 1991).

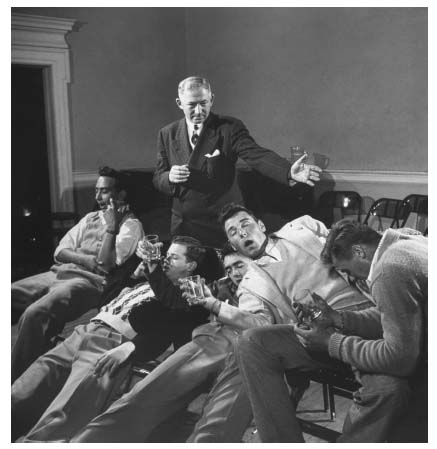

Stage hypnosis shows, in which zombie-like volunteers quack like ducks or play a wicked air guitar to the music of U-2, further contribute to popular stereotypes of hypnosis (Figure 5.1). But the wacky actions of people onstage aren’t due to a trance. Before the show even gets under way, the hypnotist selects potential performers by noting how they respond to waking suggestions. Those whose outstretched hands fall down on command when asked to imagine holding a heavy dictionary are likely to be invited onstage, whereas the remaining audience members end up watching the show from their seats. Moreover, the hypnotized volunteers do outlandish things because they feel intense pressure to respond and entertain the audience. Many stage hypnotists also use the “stage whispers” technique of whispering suggestions (“OK, when I snap my fingers, bark like a dog”) into the ears of subjects onstage (Meeker & Barber, 1971).

In the laboratory, we can easily produce all of the phenomena that people associate with hypnosis (such as hallucinations and insensitiv-ity to pain) using suggestions alone, with no mention or even hint of hypnosis. The research literature is clear: No trance or discrete state unique to hypnosis is at work. Indeed, most people who undergo hypnosis later claim they weren’t even in a trance. Kevin McConkey (1986) found that although 62% of participants endorsed the view that “hypnosis is an altered state of consciousness” before hypnosis, only 39% held this view afterwards.

Figure 5.1 Stage hypnosis shows fuel the mistaken impression that hypnosis is a distinct “trance” state closely related to sleep.

Source: George Silk//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.

If a trance isn’t required for hypnosis, what determines hypnotic suggestibility? Hypnotic suggestibility depends on people’s motivation, beliefs, imagination, and expectations, as well as their responsiveness to suggestions without hypnosis. The feeling of an altered state is merely one of the many subjective effects of suggestion, and it’s not needed to experience any other suggested effects.

Evidence of a distinct trance or altered state of consciousness unique to hypnosis would require that researchers find distinctive physiological markers of subjects’ responses to hypnotists’ suggestions to enter a trance. Despite concerted efforts by investigators, no evidence of this sort has emerged (Dixon & Laurence, 1992; Hasegawa & Jamieson, 2000; Sarbin & Slagle, 1979; Wagstaff, 1998). So there’s no reason to believe that hypnosis differs in kind rather than degree from normal wakeful-ness. Instead, hypnosis appears to be only one procedure among many for increasing people’s responses to suggestions.

That said, hypnotic suggestions can certainly affect brain functioning. In fact, studies of the neurobiology of hypnosis (Hasegawa & Jamieson, 2000) point to the brain’s anterior cingulate regions as playing a key role in alterations in consciousness during hypnosis. Although interesting, these findings “do not indicate a discrete state of hypnosis” (Hawegawa & Jamieson, 2000, p. 113). They tell us only that hypnosis changes the brain in some fashion. That’s hardly surprising, because brain functioning also changes during relaxation, fatigue, heightened attention, and a host of other states that differ only in degree from normal awareness.

Still others have claimed that certain unusual behaviors are unique to the hypnotic state. But scientific evidence for this claim has been wanting. For example, American psychiatrist Milton Erickson (1980) claimed that hypnosis is marked by several unique features, including “literalism”—the tendency to take questions literally, such as responding “Yes” to the question “Can you tell me what time it is?” Yet research demonstrates that most highly hypnotizable subjects don’t display literalism while hypnotized. Moreover, participants asked to simulate (role-play) hypnosis display higher rates of literalism than hypnotized subjects (Green et al., 1990).

So the next time you see a Hollywood movie in which the CIA transforms an average Joe into a sleepwalking zombie who prevents World War III by assassinating an evil dictator, be skeptical. Like most things that you see on the big screen, hypnosis isn’t quite what it appears to be.

Myth #20 Researchers Have Demonstrated that Dreams Possess Symbolic Meaning

“When You Understand Your Own Dreams … You’ll Be Stunned at How Quickly You Can Make LASTING, POSITIVE CHANGE In Your Life! That’s right! Your subconscious is trying very hard to TELL you something in your dreams. You just have to understand its SYMBOLIC LANGUAGE.”

Lauri Quinn Loewenberg (2008) made this pitch on her website to promote her book on dream interpretation, which contains “7 secrets to understanding your dreams.” Her site is one of many that tout the value of unraveling dreams’ symbolic meaning. So-called dream dictionaries in books, on the Internet, and in “dream software” programs, which users can download to their computers, contain databases of thousands of dream symbols that promise to help readers decode their dreams’ hidden meanings (Ackroyd, 1993). Movie and television plots also capitalize on popular beliefs about the symbolic meaning of dreams. In one episode of the HBO series, The Sopranos, Tony Soprano’s friend appeared to Tony in a dream as a talking fish, leading Tony to suspect him as an FBI informant (“fish” is a slang term for informant) (Sepinwall, 2006).

Perhaps not surprisingly, the results of a recent Newsweek poll revealed that 43% of Americans believe that dreams reflect unconscious desires (Adler, 2006). Moreover, researchers who conducted surveys in India, South Korea, and the United States discovered that 56% to 74% of people across the three cultures believed that dreams can reveal hidden truths (Morewedge & Norton, 2009). In a second study, these investigators found that people were more likely to say they would avoid flying if they imagined they dreamt of a plane crashing on a flight they planned to take than if they had the conscious thought of a plane crashing, or received a governmental warning about a high risk of a terrorist attack on an airline. These findings demonstrate that many people believe that dreams contain precious nuggets of meaning that are even more valuable than waking thoughts.

Because many of us believe that dream symbols can foretell the future, as well as achieve personal insight, dream dictionaries liberally serve up heaping portions of predictions and advice. According to Dream Central’s dream dictionary, “If you abandon something bad in your dreams you could quite possibly receive some favorable financial news.” In contrast, eating macaroni in a dream “could mean you are in for various small losses.” The Hyper dictionary of Dreams warns that dreaming of an anteater “indicates that you might be exposed to new elements, people or events, that will threaten your business discipline and work ethic.” Clearly, dreamers would do well to avoid anteaters eating macaroni, lest they risk financial trouble.

All kidding aside, many therapists trained in a Freudian tradition have long entertained the idea that the ever-changing and sometimes bizarre dream landscape is replete with symbols that, if properly interpreted, can surrender the psyche’s innermost secrets. According to Freud, dreams are the via regia—the royal road to understanding the unconscious mind —and contain “the psychology of the neurosis in a nutshell” (Freud in a letter to Fleiss, 1897, in Jones, 1953, p. 355). Freud argued that the ego’s defenses are relaxed during dreaming, leading repressed id impulses to knock at the gates of consciousness (for Freud, the “ego” was the part of the personality that interfaces with reality, the “id” the part of the personality that contains our sexual and aggressive drives). Nevertheless, these raging impulses rarely if ever reach the threshold of awareness. Instead, they’re transformed by what Freud called the “dreamwork” into symbols that disguise forbidden hidden wishes and allow dreamers to sleep peacefully. If this censorship didn’t occur, dreamers would be awakened by the unsettling eruption of repressed material—often of a sexual and aggressive nature.

Dream interpretation is one of the linchpins of the psychoanalytic method. Yet according to Freudians, dreams don’t surrender their secrets without a struggle. The analyst’s task is to go beyond the surface details of the dream, called the “manifest content,” and interpret the “latent content,” the deeper, cloaked, symbolic meaning of the dream. For example, the appearance of a scary monster in a dream (the manifest content) might symbolize the threat posed by a feared boss (the latent content). We draw dream symbols from our storehouse of life experiences, including the events we experience on the day prior to a dream, which Freud called the “day residue” (here, Freud was almost surely correct) as well as our childhood experiences.

According to Freud, dream interpretation should be guided by patients’ free associations to various aspects of the dream, thereby leaving room for individually tailored interpretations of dream content. Although Freud warned readers that dream symbols don’t bear a universal one-to-one relationship to psychologically meaningful objects, people, or events, he frequently came perilously close to violating this rule by interpreting the symbolic meaning of dreams with little or no input from his patients. For example, in his landmark book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), Freud reported that even though a woman generated no associations to the dream image of a straw hat with the middle piece bent upwards and the side piece hanging downwards, he suggested that the hat symbolized a man’s genitals. Moreover, Freud noted that penetration into narrow spaces and opening locked doors frequently symbolize sexual activity, whereas hair cutting, the loss of teeth, and beheading frequently symbolize castration. So despite his cautions, Freud treated many dream symbols as essentially universal.

Freud’s writings paved the way for a burgeoning cottage industry of dream interpretation products that shows no signs of loosening its chokehold on popular imagination. Still, most contemporary scientists reject the idea that specific dream images carry universal symbolic meaning. Indeed, close inspection of dream reports reveals that many dreams don’t appear to be disguised by symbols. Indeed, in the early stages of sleep, before our eyes begin to dart back and forth in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, most of our dreams mirror the everyday activities and concerns that occupy our minds, like studying for a test, shopping for groceries, or doing our taxes (Dorus, Dorus, & Rechtschaffen, 1971).

During REM sleep, our highly activated brains produce dreams that are sometimes illogical and charged with emotion (Foulkes, 1962; Hobson, Pace-Schott, & Stickgold, 2000). Does this occur because repressed material from the id somehow escapes censorship? Psychiatrist J. Allan Hobson doesn’t think so. In fact, Hobson’s theory of dreaming, which has garnered considerable scientific support, is so radically different from Freud’s that some have called him “the anti-Freud” (Rock, 2004). Starting in the 1960s and 1970s, at Harvard’s Laboratory of Neurophy-siology, Hobson, along with Robert McCarley, developed the activation-synthesis theory, which ties dreams to brain activity rather than the symbolic expression of unconscious wishes (Hobson & McCarley, 1977).

According to this theory (Hobson et al., 2000), when we cycle through REM periods every 90 minutes or so during sleep, various neurotransmitters (chemical messengers) orchestrate a dramatic symphony of changes that generates dreams. More specifically, surges of acetylcholine hype the brain’s emotional centers, while decreases in serotonin and norepinephrine tamp down brain areas that govern reason, memory, and attention. According to Hobson, REM dreams are our brain’s best, if imperfect, efforts to cobble together a meaningful story based on a hodgepodge of random information transmitted by the pons, a structure at the base of the brain. Under these circumstances, images that bubble up lack symbolic meaning, so dream interpretation would be haphazard at best, much like attempting to derive pearls of wisdom from gibberish.

Still, to give Freud his due, he may have been right on at least two important counts: Our daily thoughts and feelings can influence our dreams, and emotion plays a powerful role in dreaming. Nevertheless, the fact that the emotional centers of the brain become supercharged during dreaming as the forebrain responsible for logical thinking shuts down (Solms, 1997, 2000) doesn’t mean that dreams are attempts to fulfill the id’s wishes. Nor does it mean that dreams use symbols to disguise their true meaning.

Rather than relying on a dream dictionary to foretell the future or help you make life decisions, it probably would be wisest to weigh the pros and cons of differing courses of action carefully, and consult trusted friends and advisers. Still, as far as your dreams go, it may be a good idea to avoid anteaters eating macaroni.

Myth #21 People Can Learn Information, like New Languages, while Asleep

Imagine that you could learn all of the information in this book while getting just a few nights of sound sleep. You could pay someone to tape record the entire book, play the recording over the span of several weeknights, and voilà—you’d be all done. You could kiss goodbye to all of those late nights reading about psychological misconceptions.

As in many areas of psychology, hope springs eternal. Indeed, many proponents of sleep-assisted learning—learning new material while asleep (technically called “hypnopaedia”)—have advanced many strong claims regarding this technique’s potential. One website (http://www. sleeplearning.com/) informs visitors that:

Sleep learning is a way to harness the power of your subconscious while you sleep, enabling you to learn foreign languages, pass exams, undertake professional studies and implement self-growth by using techniques based on research conducted all over the world with great success. … It’s the most incredible learning aid for years.

The website offers a variety of CDs that can purportedly help us to learn languages, stop smoking, lose weight, reduce stress, or become a better lover, all while we’re comfortably catching up on our zzzzs. The site even goes so far as to say that the CDs work better when people are asleep than awake. Amazon.com features a host of products designed to help us learn while sleeping, including CDs that claim to help us learn Spanish, Romanian, Hebrew, Japanese, and Mandarin Chinese while playing subliminal messages (see Myth #5) to us while we’re sound asleep. Perhaps not surprisingly, the results of one survey revealed that 68% of undergraduates believed that people can learn new information while asleep (Brown, 1983).

Sleep-assisted learning is also a common fixture in many popular books, television programs, and films. In Anthony Burgess’s (1962) brilliant but horrifying novel, A Clockwork Orange, later made into an award-winning film by director Stanley Kubrick, government officials attempt unsuccessfully to use sleep-assisted learning techniques to transform the main character, Alex, from a classic psychopath into a respectable member of society. In an episode of the popular television program, Friends, Chandler Bing (portrayed by Matthew Perry) attempts to quit smoking by playing a tape containing suggestions to stop smoking during sleep. Nevertheless, unbeknownst to him, the tape contained the suggestion, “You are a strong and confident woman,” leading Chandler to behave in a feminine way in daily life.

But does the popular conception of sleep-assisted learning stack up to its advocates’ impressive claims? One reason for initial optimism about sleep-assisted learning stems from findings that people sometimes incorporate external stimuli into their dreams. Classic research by William Dement and Edward Wolpert (1958) demonstrated that presenting dreaming subjects with stimuli, like squirts of water from a syringe, often leads them to weave these stimuli into their dreams. For example, in Dement and Wolpert’s work, one participant sprayed with water reported a dream of a leaky roof after being awakened shortly thereafter. Later researchers showed that anywhere from 10–50% of participants appear to incorporate external stimuli, such as bells, red lights, and voices, into their dreams (Conduit & Coleman, 1998; Trotter, Dallas, & Verdone, 1988). Nevertheless, these studies don’t really demonstrate sleep-assisted learning, because they don’t show that people can integrate complex new information, like mathematical formulas or new words from foreign languages, into their dreams. Nor do they show that people can later recall these externally presented stimuli in everyday life if they’re not awakened from their dreams.

To investigate claims regarding sleep-assisted learning, investigators must randomly assign some participants to hear audiotaped stimuli, like words from a foreign language, while sleeping and others to hear a “control” audiotape consisting of irrelevant stimuli, and later examine their knowledge of these stimuli on a standardized test. Interestingly, some early findings on sleep-assisted learning yielded encouraging results. One group of investigators exposed sailors to Morse code (a shorthand form of communication that radio operators sometimes use) while asleep. These sailors mastered Morse code three weeks faster than did other sailors (Simon & Emmons, 1955). Other studies from the former Soviet Union also seemed to provide support for the claim that people could learn new material, such as words or sentences, while listening to tape recordings during sleep (Aarons, 1976).

Yet these early positive reports neglected to rule out a crucial alternative explanation: the tape recordings may have awakened the subjects! The problem is that almost all of the studies showing positive effects didn’t monitor subjects’ brain waves to ensure that they were actually asleep while listening to the tapes (Druckman & Bjork, 1994; Druckman & Swets, 1988). Better controlled studies that have monitored subjects’ brain waves to make sure they’re clearly asleep have offered little or no evidence for sleep-assisted learning (Logie & Della Sala, 1999). So to the extent that sleep-learning tapes “work,” it’s probably because subjects hear snatches of them while drifting in and out of sleep.

Listening to the tapes while fully awake is not only far more efficient but probably more effective. As for that quick fix for mastering new knowledge or reducing stress, we’d recommend saving your money about the tapes and just getting a good night’s sleep.

Myth #22 During “Out-of-Body” Experiences, People’s Consciousness Leaves Their Bodies

Since biblical times, if not earlier, people have speculated that out-of-body experiences (OBEs) provide conclusive evidence that consciousness can leave the body. Consider the following example of an OBE reported by a woman who had an internal hemorrhage following an operation to remove her uterus:

I was awake and aware of my surroundings. A nurse came in to take my blood pressure every half hour. On one occasion I remember her taking my blood pressure and then running out of the room, which I thought was unusual. I don’t remember anything more after that consciously, but I was then aware of being above my body as if I was floating on the ceiling and looking down at myself in the hospital bed with a crowd of doctors and nurses around me. (Parnia, 2006, p. 54)

Or take this description from a woman on the operating table:

… while I was being operated on I saw some very odd lights flashing and heard a loud keening noise. Then I was in the operating theatre above everyone else but just high enough to see over everyone’s shoulders. I was surprised to see everyone dressed in green … I looked down and wondered what they were all looking at and what was under the cover on the long table. I saw a square of flesh, and I thought, “I wonder who it is and what they are doing.” I then realized it was me. (Blackmore, 1993, p. 1)

These reports are typical of OBEs, in which people claim to be floating above or otherwise disengaged from their bodies, observing themselves from a distance. Such fascinating alterations in consciousness prompted ancient Egyptians and Greeks, and others who experienced OBEs throughout history, to conclude that they reveal that consciousness can be independent of the physical body.

People in virtually all cultures report OBEs (Alcock & Otis, 1980). They’re surprisingly common: About 25% of college students and 10% of members of the general population report having experienced one or more of them (Alvarado, 2000). Many people in the general public assume that OBEs occur most frequently when people are near death, such as when they’re drowning or experiencing a heart attack. They’re wrong. Although some OBEs occur during life-threatening circumstances (Alvarado, 2000), most occur when people are relaxed, asleep, dreaming, medicated, using psychedelic drugs, anesthetized, or experiencing seizures or migraine headaches (Blackmore, 1982, 1984; Green, 1968; Poynton, 1975). OBEs also occur in people who can spontaneously experience a wide variety of alterations in consciousness (Alvarado, 2000). People who often fantasize in their everyday lives to the extent that they lose an awareness of their bodies are prone to OBEs, as are those who report other strange experiences, like hallucinations, perceptual distortions, and unusual bodily sensations (Blackmore, 1984, 1986).

Some people report being able to create OBEs on command, and to mentally visit distant places or “spiritual realms” during their journeys out of body, a phenomenon called “astral projection” or “astral travel.” One Internet site dubs the study of OBEs “projectiology,” and claims, “Based on projectiological data, the projection of the consciousness is a real experience that takes place in a dimension other than the physical. Conscious projectors are able to temporarily leave the restriction of their physical body and access non-physical dimensions where they discover new aspects of the nature of consciousness” (Viera, 2002). Believers in “Eckankar,” who claim to practice the “science of soul travel,” contend that their senses are enhanced and that they experience ecstatic states of spiritual awareness during purposefully created OBEs. Instructions for producing OBEs to achieve spiritual enlightenment and to remotely view far-away places, including alien worlds, are widely available on the Internet, and in books and articles.

Tempting as it is to speculate that our consciousness can break free of the shackles of our physical bodies, research doesn’t support this hypothesis. A straightforward way to test the notion that consciousness actually exits the body is to find out whether people can report accurately on what they “see” at a remote location during an OBE. Researchers typically test people who claim to be able to produce OBEs at will, and instruct them to “travel” to a pre-arranged location and describe what they observe when they return to their bodies. Scientists can determine the accuracy of the descriptions because they know what’s physically at the site. Participants often report that they can “leave their bodies” when instructed, and that they can see what’s happening at the target location, like a ledge in their apartment 10 feet above their bed. Yet investigators have found that their reports are almost always inaccurate, as gauged by judges’ comparisons of these reports with the actual physical characteristics of the target locations. At best what they describe could just be a “good guess” in the rare cases that they’ve been accurate. Even when a few scattered researchers have reported seemingly positive results, others haven’t replicated them (Alvarado, 2000).

If people don’t actually leave their bodies during an OBE, what explains their dramatic alterations in consciousness? Our sense of “self” depends on a complex interplay of sensory information. One hypothesis is that OBEs reflect a disconnection between individuals’ sense of their bodies and their sensations. Consistent with this possibility, research suggests that OBEs arise from the failure of different brain areas to integrate information from different senses (Blanke & Thut, 2007). When we reach for a knife and feel its sharp edges, we have a strong sense not only of its reality, but of ourselves as active agents.

Two studies suggest that when our senses of touch and vision are scrambled, our usual experience of our physical body becomes disrupted too. In Henrik Ehrsson’s (2007) research, participants donned goggles that permitted them to view a video display of themselves relayed by a camera placed behind them. This setup created the weird illusion that their bodies, viewed from the rear, actually were standing in front of them. In other words, participants could literally “see” their bodies at a second location, separate from their physical selves. Ehrsson touched participants in the chest with a rod while he used cameras to make it appear that the visual image in the display was being touched at the same time. Participants reported the eerie sensation that their video double was also being touched, thus sensing they were at a location outside their physical bodies.

Bigna Lenggenhager and her colleagues (Lenggenhager, Tadi, Metzinger, & Blanke, 2007) concocted a similar virtual-reality setup. After participants viewed their virtual double, researchers touched them on their backs at the same time as they touched their projected alter egos. The researchers then blindfolded them, moved them from their original position, and asked them to return to the original spot. Interestingly, subjects repositioned themselves closer to the location where their double was projected than to the place where they stood initially. The fact that subjects were drawn to their alter egos suggests that they experienced their location outside their own bodies.

Numerous researchers have tried to pin down the brain location of OBEs. In the laboratory, several have successfully induced OBEs—reports of one’s sense of self separated from one’s body—by stimulating the temporal lobe, particularly the place where the brain’s right temporal and parietal lobes join (Blanke, Ortigue, Landis, & Seeck, 2002; Persinger, 2001; Ridder, Van Laere, Dupont, Menovsky, & Van de Heyning, 2007).

One can certainly question the relevance of laboratory findings to OBEs that occur in everyday life, and it’s possible that the latter stem from different causes than the former. Still, the fact that scientists can produce experiences that closely resemble spontaneously occurring OBEs suggests that our consciousness doesn’t actually leave our bodies during an OBE, despite the striking subjective conviction that it does.

Chapter 5: Other Myths to Explore

| Fiction | Fact |

| Relaxation is necessary for hypnosis to occur. | People can be hypnotized while exercising vigorously. |

| People are unaware of their surroundings during hypnosis. | Hypnotized people are aware of their surroundings and can recall the details of conversations overheard during hypnosis. |

| People have no memory for what took place while hypnotized. | “Posthypnotic amnesia” doesn’t occur unless people expect it to occur. |

| Most modern hypnotists use a swinging watch to induce a hypnotic state. | Virtually no modern hypnotists use watches to induce hypnosis. |

| Some hypnotic inductions are more effective than others. | A wide range of hypnotic inductions are about equally effective. |

| People who respond to many hypnotic suggestions are gullible. | People who respond to many hypnotic suggestions are no more gullible than people who respond to few suggestions. |

| Hypnosis can lead people to perform immoral acts they wouldn’t otherwise perform. | There’s little or no evidence that one can make hypnotized individuals engage in unethical acts against their will. |

| Hypnosis allows people to perform acts of great physical strength or skill. | These same acts can be performed by highly motivated subjects without hypnosis. |

| People can’t lie under hypnosis. | Studies show that many subjects can lie while hypnotized. |

| The primary determinant of hypnosis is the skill of the hypnotist. | The main determinant of hypnosis is the subject’s hypnotic suggestibility. |

| People can remain permanently “stuck” in hypnosis. | People can come out of a hypnotic state even if the hypnotist leaves. |

| Extremely high levels of motivation can allow people to firewalk over burning hot coals. | Firewalking can be accomplished by anyone who walks quickly enough, because coals are poor conductors of heat. |

| Dreams occur in only a few seconds, although they take much longer to recount later. | This belief, held by Sigmund Freud and others, is false; many dreams last a half hour or even more. |

| Our brains “rest” during sleep. | During rapid eye movement sleep, our brain is in a state of high activity. |

| Sleeping pills are a good long-term treatment for insomnia. | Prolonged use of sleeping pills often causes rebound insomnia. |

| “Counting sheep” helps people to fall asleep. | The results of one study show that asking insomniacs to count sheep in bed doesn’t help them fall asleep. |

| Falling asleep the moment one’s head hits the pillow is a sign of a healthy sleeper. | Falling asleep the moment one’s head hits the pillow is a sign of sleep deprivation; most healthy sleepers take 10–15 minutes to fall asleep after going to bed. |

| Many people never dream. | Although many people claim that they never dream, virtually all people eventually report dreams when awakened from REM sleep. |

| Most dreams are about sex. | Only a small minority, perhaps 10% or less, of dreams contain overt sexual content. |

| Most dreams are bizarre in content. | Studies show that most dreams are relatively realistic approximations of waking life. |

| People dream only in black and white. | Most people report color in their dreams. |

| Blind people don’t dream. | Blind people do dream, although they only experience visual images in their dreams if they had sight prior to about age 7. |

| If we dream that we die, we’ll actually die. | Many people have dreamt of their deaths and lived to tell about it. |

| Dreams occur only during REM sleep. | Dreams also occur in non-REM sleep, although they tend to be less vivid and more repetitive in content than REM dreams. |

| People can use lucid dreaming to improve their mental adjustment. | There’s no research evidence that becoming aware of the fact that one is dreaming—and using this awareness to change one’s dreams—can enhance one’s psychological health. |

| Most sleepwalkers are acting out their dreams; most sleeptalkers are verbalizing them. | Sleepwalking and sleeptalking, which occur in non-REM sleep, aren’t associated with vivid dreaming. |

| Sleepwalking is harmless. | Sleepwalkers often injure themselves by tripping or bumping into objects. |

| Sleepwalking is associated with deep-seated psychological problems. | There’s no evidence that sleepwalking is associated with severe psychopathology. |

| Awakening a sleepwalker is dangerous. | Awakening a sleepwalker isn’t dangerous, although sleepwalkers may be disoriented upon waking. |

| Transcendental meditation is a uniquely effective means of achieving relaxation. | Many studies suggest that meditation yields no greater physiological effects than rest or relaxation alone. |

Sources and Suggested Readings

To explore these and other myths about consciousness, see Cardena, Lynn, and Krippner (2000); Harvey and Payne (2002); Hines (2003); Holmes (1984); Nash (1987); Nash (2001); Mahowald and Schenk (2005); Piper (1993); Squier and Domhoff (1998); Wagstaff (2008).