10

DISORDER IN THE COURT

Myths about Psychology and the Law

Myth #43 Most Mentally Ill People Are Violent

Let’s start off with a quick quiz for you movie buffs out there. What do the following Hollywood films have in common: Psycho, Halloween, Friday the 13th, Misery, Summer of Sam, Texas Chain Saw Massacre, Nightmare on Elm Street, Primal Fear, Cape Fear, and Dark Knight?

If you guessed that they all feature a mentally ill character who’s violent, give yourself a point.

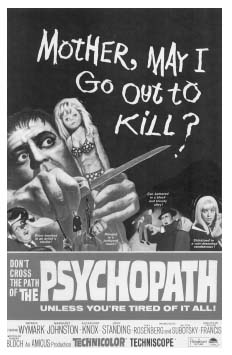

These films are the rule rather than the exception. About 75% of films depicting a character with a serious mental illness portray that character as physically aggressive, even homicidal (Levin, 2001; Signorielli, 1989; Wahl, 1997). Movies and television shows portraying “psychopathic killers” and “homicidal maniacs” have become a dime a dozen in Hollywood. Prime-time television programs depict characters with mental illness as engaging in violence about 10 times more often than other characters, and 10 to 20 times more often than the average person (Diefenbach, 1997; Stout, Villegas, & Jennings, 2004; Figure 10.1).

The coverage of mental illness in the news is scarcely different. In one study, 85% of news stories that covered ex-psychiatric patients focused on their violent crimes (Shain & Phillips, 1991). Of course, these findings won’t come as any surprise to those familiar with the unspoken mottos of news organizations: “If it bleeds it leads; it if burns, it earns.” The news media feeds on sensationalism, so stories of mentally ill people with histories of violence are virtually guaranteed to garner a hefty chunk of attention.

Figure 10.1 Many films fuel the public misperception of the mentally ill as frequently or even usually violent. Ironically, most psychopaths aren’t even violent (see “Other Myths to Explore”).

Source: Photofest.

Because of the availability heuristic (see p. 89), our tendency to judge the frequency of events with the ease with which they come to mind, this media coverage virtually guarantees that many people will think “violence” whenever they hear “mental illness” (Ruscio, 2000). This heuristic can contribute to illusory correlations (see Introduction, p. 12) between two phenomena, in this case violence and mental illness. Widespread media coverage of Andrea Yates’ tragic drowning of her five children in 2001 and Seung-Hui Cho’s horrific shootings of 32 students and faculty at Virginia Tech in 2007 have almost surely strengthened this connection in people’s minds, as both Yates and Cho suffered from severe mental disorders (Yates was diagnosed with psychotic depression, and Cho apparently exhibited significant symptoms of schizophrenia). Indeed, in one study, reading a newspaper story about a murder of a 9-year-old by a mentally ill patient produced a significant increase in the perception that the mentally ill are dangerous compared with a control condition (Thornton & Wahl, 1996).

Not surprisingly, surveys reveal that the close link between mental ill ness and violence in the popular media is paralleled in the minds of the general public. One survey demonstrated that about 80% of Americans believe that mentally ill people are prone to violence (Ganguli, 2000). This perception of heightened risk holds across a broad range of dis orders, including alcoholism, cocaine dependence, schizophrenia, and even depression (Angermeyer & Dietrich, 2006; Link, Phelan, Bresnahan, Stueve, & Pescosolido, 1999). In addition, between 1950 and 1996, the proportion of American adults who perceived the mentally ill as violent increased substantially (Phelan, Link, Stueve, & Pescosolido, 2000). This increase is ironic, because research suggests that the percentage of murders committed by the mentally ill has declined over the past four decades (Cutcliffe & Hannigan, 2001). Whatever the origins of this belief, it begins early in life. Studies show that many children as young as 11 to 13 years of age assume that most mentally ill people are dangerous (Watson et al., 2004).

Yet commonplace public beliefs about mental illness and violence don’t square with the bulk of the research evidence (Applebaum, 2004; Teplin, 1985). Admittedly, most studies point to a modestly heightened risk of violence among people with severe mental illnesses, such as schizo phrenia and bipolar disorder, once called manic depression (Monahan, 1992).

Yet even this elevated risk appears limited to only a relatively small subset of people with these illnesses. For example, in most studies, people with paranoid delusions (such as the false belief of being pursued by the Central Intelligence Agency) and substance abuse disorders (Harris & Lurigio, 2007; Steadman et al., 1998; Swanson et al., 1996), but not other mentally ill people, are at heightened risk for violence. Indeed, in some recent studies, severely mentally ill patients without substance abuse disorders showed no higher risk for violence than other individuals (Elbogen & Johnson, 2009). Nevertheless, psychiatric patients who take their medication regularly aren’t at elevated risk for violence compared with members of the general population (Steadman et al., 1998). There’s also some evidence that patients with “command hallucinations”— hearing voices instructing a person to commit an act like a murder—are at heightened risk for violence (Junginger & McGuire, 2001; McNiel, Eisner, & Binder, 2000).

Still, the best estimates suggest that 90% of more of people with serious mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, never commit violent acts (Hodgins et al., 1996). Moreover, severe mental illness probably accounts for only about 3-5% of all violent crimes (Monahan, 1996; Walsh, Buchanan, & Fahy, 2001). In fact, people with schizophrenia and other severe mental disorders are far more likely to be victims than perpetrators of violence (Teplin, McClelland, Abram, & Weiner, 2005), probably because their weakened mental capacity renders them vulner able to attacks by others. Furthermore, most major mental disorders, including major depression and anxiety disorders (such as phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorder), aren’t associated with a heightened risk of physical aggression.

There is, though, a hint of a silver lining surrounding the huge gray cloud of public misunderstanding. Research suggests that the portrayal of mental illness in the news and entertainment media may gradually be changing. From 1989 to 1999, the percentage of news stories about the mentally ill that contained descriptions of violence decreased (Wahl, Wood, & Richards, 2002). In addition, recent films such as A Beautiful Mind (2001), which portray people with severe mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, as nonviolent and as coping successfully with their psychiatric symptoms, may help to counter the public’s erroneous perception of a powerful link between mental illness and violence. Interestingly, cross-cultural research suggests that the perception of a markedly heightened risk of violence among people with schizophrenia may be absent in some regions, including Siberia and Mongolia (Angermeyer, Buyantugs, & Kenzine, 2004), perhaps stemming from their limited access to media coverage. These findings give us further reason for hope that the perception of a greatly heightened risk for violence among the mentally ill isn’t inevitable.

Myth #44 Criminal Profiling Is Helpful in Solving Cases

For most of October, 2002, the citizens of Virginia, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. were virtually held hostage in their homes. During 23 seemingly endless days, 10 innocent people were killed and 4 others wounded in a nightmarish series of shootings. One person was shot while mowing a lawn, another while reading a book on a city bench, another after leaving a store, another while standing in a restaurant parking lot, and several others while walking down the street or pumping gasoline. The shootings appeared entirely random: The victims included Whites and African Americans, children and adults, men and women. Terrified and bewildered, many residents of the Washington Beltway area avoided going out unless absolutely necessary, and dozens of schools ordered virtual lockdowns, cancelling all outdoor recesses and gym classes.

As the shooting spree continued with no clear end in sight, legions of criminal profilers took to the television airwaves to offer their conjectures about the sniper’s identity. Criminal profilers are trained professionals who claim to be able to infer a criminal’s personality, behavioral, and physical characteristics on the basis of specific details about one or more crimes (Davis & Follette, 2002; Hicks & Sales, 2006). In this way, they supposedly can help investigators identify the person responsible for the crime or crimes in question (Douglas, Ressler, Burgess, & Hartman, 1986). The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) alone employs criminal profilers in about 1,000 cases every year (Snook, Gendreau, Bennell, & Taylor, 2008).

In the Beltway sniper case, most of the criminal profilers interviewed by the media agreed on one thing: The killer was probably a White male (Davis & Morello, 2002; Kleinfield & Goode, 2002). After all, these two characteristics matched the profile of most serial killers. Other pro filers maintained that the killer didn’t have children, and others that he wasn’t a soldier, as a soldier would presumably have used highly accurate military bullets rather than the relatively crude bullets found at the shootings. Still other profilers speculated that the killer would be in his mid-20s, as the average age of sniper killers is 26 (Gettleman, 2002; Kleinfield & Goode, 2002).

Yet when “the sniper” was finally captured on October 24, most of the expert media profilers were in for a surprise. For one thing, “the sniper” wasn’t one person: the murders had been committed by a team of two males, John Allen Muhammad and Lee Boyd Malvo. What’s more, both men were African-American, not White. Contrary to what many profilers had predicted, Muhammad had four children and was a former soldier. And neither killer was in his mid-20s: Muhammad was 41, Malvo 17.

The infamous Beltway sniper case highlights two points. First, this case underscores the fact that criminal profiling has become an indelible part of the landscape of popular culture. The 1991 Academy Award-winning film, The Silence of the Lambs, starring Jodie Foster as a young intern in training as an FBI profiler, stoked many Americans’ fascination with criminal profiling. At least nine other films, including Copycat (1995) and Gothika (2003), also feature criminal profilers in prominent roles. And several popular television series, most notably Profiler, Millennium, Criminal Minds, and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, accord prominent billing to criminal profilers. Today, criminal profilers like Pat Brown and Clint van Zandt are featured routinely on television programs focused on crime investigations, such as Fox News’ On the Record (hosted by Greta van Susteren) and CNN’s Nancy Grace. These films or programs seldom offer even a hint of skepticism regarding criminal profilers’ predictive capacities (Muller, 2000).

The popularity of profiling in the media is mirrored by perceptions of its effectiveness among many mental health professionals and law enforcement officers. In a survey of 92 psychologists and psychiatrists with expertise in the law, 86% agreed that criminal profiling “is a useful tool for law enforcement,” although only 27% believed it was scientifically established enough to be admitted into courts of law (Torres, Boccaccini, & Miller, 2006). In another survey of 68 U.S. police officers, 58% said that profiling was helpful in directing criminal invest igations and 38% that it was helpful in fingering suspects (Trager & Brewster, 2001).

Second, the wildly inaccurate guesses of many profilers in the Beltway sniper case raise a crucial question: Does criminal profiling work? To answer this question, we need to address what we mean by “work.” If we mean “Does criminal profiling predict perpetrators’ characteristics better than chance?,” the answer is probably yes. Studies show that professional profilers can often accurately guess some of the character istics of criminals (such as whether they’re male or female, young or old) when presented with detailed case file information regarding specific crimes, such as rapes and murders, and they perform better than we’d do by flipping a coin (Kocsis, 2006).

But these results aren’t terribly impressive. That’s because criminal profilers may be relying on “base rate information,” that is, data on the characteristics of criminals who commit certain crimes that are readily available to anyone who bothers to look them up. For example, about 90% of serial killers are male and about 75% are White (Fox & Levin, 2001). So one needn’t be a trained profiler to guess that a person re sponsible for a string of murders is probably a White male; one will be right more than two thirds of the time by relying on base rates alone. We can derive some base rate information even without consulting formal research. For example, it doesn’t take a trained profiler to figure out that a man who brutally murdered his wife and three children by stabbing them repeatedly probably “had serious problems controlling his temper.”

A better test of whether criminal profiling works is to pit professional profilers against untrained individuals. After all, profiling is supposedly a technique that requires specialized training. When one puts criminal profiling to this more stringent test, the results are decidedly unimpres sive. In most studies, professional profilers barely do any better than untrained persons in inferring the personality traits of actual murderers from details about their crimes (Homant & Kennedy, 1998). In at least one study, homicide detectives with extensive experience in criminal invest igation and police officers generated less accurate profiles of a murderer than did chemistry majors (Kocsis, Hayes, & Irwin, 2002).

A meta-analysis (see p. 32) of four well-controlled studies revealed that trained profilers did only slightly better than non-profilers (college students and psychologists) at estimating the overall characteristics of offenders from information about their crimes (Snook, Eastwood, Gendreau, Goggin, & Cullen, 2007). They fared no better or even slightly worse than non-profilers at gauging offenders’ (a) physical character istics, including gender, age, and race, (b) thinking processes, including motives and guilt regarding the crime, and (c) personal habits, includ ing marital status and education. Even the finding that profilers did slightly better on overall offender characteristics than non-profilers is hard to interpret, as profilers may be more familiar than non-profilers with base rate information concerning criminals’ characteristics (Snook et al., 2008). Non-profilers with just a bit of education regarding these base rates or motivation to look them up might do as well as profilers, although researchers haven’t yet investigated this possibility.

Given that the scientific support for criminal profiling is so feeble, what accounts for its immense popularity? There are a host of potential reasons (Snook et al., 2008; in press), but we’ll focus on three here. First, media reports on profilers’ hits—that is, successful predictions—far outnumber their misses (Snook et al., 2007). This tendency is especially problematic because profilers, like police psychics, typically toss out scores of guesses about the criminal’s characteristics in the hopes that at least a few of them will prove correct. As the old saying goes, “Throw enough mud at the wall and some of it will stick.” For example, a few profilers guessed correctly that the Beltway sniper murders were conducted by two people (Gettleman, 2002). But it’s not clear whether these guesses were anything more than chance hits.

Second, what psychologists have termed the “expertise heuristic” (Reimer, Mata, & Stoecklin, 2004; Snook et al., 2007) probably plays a role too. According to this heuristic (recall from the Introduction, p. 15, that a “heuristic” is a mental shortcut), we place particular trust in people who describe themselves as “experts.” Because most profilers claim to possess specialized expertise, we may find their assertions especially persuasive. Studies show that police officers perceive profiles to be more accurate when they believe they’re generated by professional profilers as opposed to non-experts (Kocsis & Hayes, 2004).

Third, the P. T. Barnum Effect—the tendency to find vague and general personality descriptions believable (Meehl, 1956; see Myths #36 and 40) is probably a key contributor to the popularity of criminal profiling (Gladwell, 2007). Most profilers sprinkle their predictions liberally with assertions that are so nebulous as to be virtually untestable (“The killer has unresolved self-esteem problems”), so general that they apply to just about everyone (“The killer has conflicts with his family”), or that rely on base rate information about most crimes (“The killer probably abandoned the body in or near a body of water”). Because many of their predictions are difficult to prove wrong or bound to be right regardless of who the criminal turns out to be, profilers may seem to be uncannily accurate (Alison, Smith, Eastman, & Rainbow, 2003; Snook et al., 2008). Consistent with this possibility, the results of one study revealed that police officers found a “Barnum” profile containing ambiguous state ments (such as “the offender is an inappropriately immature man for his years” and “the offense … represented an escape from a humdrum, unsatisfying life”) to fit an actual criminal just as well as a genuine profile constructed around factual details of the criminal’s life (Alison, Smith, & Morgan, 2003).

Just as P. T. Barnum quipped that he liked to give “a little something to everybody” in his circus acts, many seemingly successful criminal profilers may put just enough in each of their profiles to keep law enforcement officials satisfied. But do profilers actually do better than the average person in solving crimes? At least at present, the verdict is “No, not beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Myth #45 A Large Proportion of Criminals Successfully Use the Insanity Defense

After giving a speech on the morning of March 30, 1981, U.S. President Ronald Reagan emerged from the Washington Hilton hotel in the nation’s capital. Surrounded by security guards, a smiling Reagan walked toward his president limousine, waving to the friendly crowd gathered outside the hotel. Seconds later, six shots rang out. One of them hit a secret service agent, one hit a police officer, another hit the President’s press secretary James Brady, and another hit the President himself. Lodged only a few inches from Reagan’s heart, the bullet came perilously close to killing America’s 40th President. Following surgery, the President recovered fully, but Brady suffered permanent brain damage.

The would-be assassin was a previously unknown 26-year-old man named John Hinckley. Hinckley, it turned out, had fallen in love from a distance with actress Jodie Foster, then a student at Yale University. Hinckley had recently seen the 1976 film Taxi Driver, which featured Foster as a child prostitute, and identified powerfully with the character of Travis Bickle (portrayed brilliantly by actor Robert De Niro), who harbored rescue fantasies toward Foster’s character. Hinckley repeatedly left love notes for Foster and even reached her several times by phone in his dorm room at Yale, but his desperate efforts to woo her were to no avail. Hinckley’s love for Foster remained unrequited. Hopelessly delusional, Hinckley believed that by killing the president he could make Foster come to appreciate the depth of his passion for her.

In 1982, following a combative trial featuring dueling psychiatric experts, the jury found Hinckley not guilty by reason of insanity. The jury’s surprising decision generated an enormous public outcry; an ABC News poll revealed that 76% of Americans objected to the verdict. This negative reaction was understandable. Many Americans found the notion of acquitting a man who shot the president in broad daylight to be morally repugnant. Moreover, because the assassination attempt was captured on videotape, most Americans had witnessed the event with their own eyes. Many of them probably thought, “Wait a minute; I saw him do it. How on earth could he be found not guilty?” Yet the insanity defense doesn’t deal with the question of whether the defendant actually committed the criminal act (what legal experts call actus reas, or guilty act) but rather with the question of whether the defendant was psychologically responsible for this act (what legal experts call mens rea, or guilty mind).

Since the Hinckley trial, Americans have witnessed numerous other high-profile cases featuring the insanity plea, including those of Jeffrey Dahmer (the Milwaukee man who killed and cannibalized a number of his victims) and Andrea Yates (the Texas woman who drowned five of her children). In all of these cases, juries struggled with the difficult question of whether an individual who committed murder was legally responsible for the act.

The first trick to understanding the insanity defense is to recognize that sanity and insanity are legal, not psychiatric, terms. Despite their informal use in everyday language (“That man on the street is talking to himself; he must be insane”), these terms don’t refer to whether a person is psychotic—that is, out of touch with reality—but rather to whether that person was legally responsible at the time of the crime. Yet determining criminal responsibility is far from simple. There are several versions of the insanity verdict, each of which conceptualizes criminal responsibility a bit differently.

Most U.S. states use some variant of the M’Naughten rule, which requires that to be ruled insane, defendants must have either not known what they were doing at the time of the act or not known that what they were doing was wrong. This rule focuses narrowly on the question of cognition (thinking): Did the defendant understand the meaning of his or her criminal act? For example, did a man who murdered a gas station attendant understand that he was breaking the law? Did he believe that he was murdering an innocent person, or did he believe that he was murdering the devil dressed up as a gas station attendant?

For a time, several other states and most federal courts adopted the criteria outlined by the American Law Institute (ALI), which required that to be ruled insane, defendants must have either not understood what they were doing or been unable to control their impulses to conform to the law. The ALI guidelines broadened the M’Naughten rule to include both cognition and volition: the capacity to control one’s impulses.

Because Hinckley was acquitted under the ALI guidelines, many states responded to this verdict by tightening these guidelines. Indeed, most states that use the insanity verdict have now returned to stricter M’Naughten-like standards. Moreover, following the Hinckley verdict, more than half of the states considered abolishing the insanity verdict entirely (Keilitz & Fulton, 1984) and four states—Montana, Idaho, Utah, and Kansas—have done so (Rosen, 1999). Still other states introduced a variant of the insanity verdict known as “guilty but mentally ill” (GBMI). Under GBMI, judges and juries can consider a criminal’s mental illness during the sentencing phase, but not during the trial itself.

As the intense public reaction to the Hinckley verdict illustrates, many people hold strong opinions concerning the insanity defense. Surveys show that most Americans believe that criminals often use the insanity defense as a loophole to escape punishment. One study revealed that the average layperson believes that the insanity defense is used in 37% of felony cases, and that this defense is successful 44% of the time. This survey also demonstrated that the average layperson believes that 26% of insanity acquittees are set free, and that these acquittees spend only about 22 months in a mental hospital following their trials (Silver, Cirincione, & Steadman, 1994). Another survey indicated that 90% of members of the general public agreed that “the insanity plea is used too much. Too many people escape responsibilities for crimes by pleading insanity” (Pasewark & Seidenzahl, 1979).

Many politicians share these perceptions. For example, Richard Pasewark and Mark Pantle (1979) asked state legislators in Wyoming to estimate the frequency of use of the insanity defense in their state. These politicians estimated that 21% of accused felons had used this defense, and that they were successful 40% of the time. Moreover, many prominent politicians have lobbied strenuously against the insanity defense. In 1973, then U.S. President Richard Nixon made the abolition of the insanity defense the centerpiece of his nationwide effort to fight crime (because Nixon resigned over the Watergate scandal only a year later, this initiative never gathered much steam). Many other politicians have since called for an end to this verdict (Rosen, 1999).

Yet laypersons’ and politicians’ perceptions of the insanity defense are wildly inaccurate. Although most Americans believe that the use of the insanity defense is widespread, data indicate that this defense is raised in less than 1% of criminal trials and that it’s successful only about 25% of the time (Phillips, Wolf, & Coons, 1988; Silver et al., 1994). For example, in the state of Wyoming between 1970 and 1972, a grand total of 1 (!) accused felon successfully pled insanity (Pasewark & Pantle, 1979). Overall, the public believes that this defense is used about 40 times more often than it actually is (Silver et al., 1994).

The misperceptions don’t end there. Members of the general public also overestimate how many insanity acquittees are set free; the true proportion is closer to only 15%. For example, Hinckley has remained in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, a famous psychiatric facility in Washington, DC, since 1982. Moreover, the average insanity acquittee spends between 32 and 33 months in a psychiatric hospital, considerably longer than the public estimates (Silver et al., 1994). In fact, the results of several stud ies indicate that criminals acquitted on the basis of an insanity verdict typically spend at least as long, if not longer, in an institution (such as a psychiatric hospital) than criminals who are convicted (Rodriguez, 1983).

How did these misperceptions of the insanity defense arise? We Americans live increasingly in a “courtroom culture.” Between Court TV, CSI, Judge Judy, Law and Order, CNN’s Nancy Grace, and media coverage of the trials of celebrities (such as O. J. Simpson, Robert Blake, and Michael Jackson), we’re inundated on an almost daily basis with information about the legal system and its innermost workings. Nevertheless, this information can be deceptive, because we hear far more about the sensational than the typical cases, which are, after all, typical. Indeed, the media devotes considerably more coverage to legal cases in which the insanity defense is successful, like Hinckley’s, than to those in which it isn’t (Wahl, 1997). Because of the availability heuristic (see p. 89), we’re more likely to hear about and remember successful uses of the insanity defense than unsuccessful uses.

As is so often the case, the best antidote to public misperception is accurate knowledge. Lynn and Lauren McCutcheon (1994) found that a brief fact-based report on the insanity defense, compared with a news program on crime featuring this defense, produced a significant decrease in undergraduates’ misconceptions concerning the insanity defense (such as the notion that uses of the insanity defense are widespread in the criminal justice system and that most such uses are successful). These findings give us cause for hope, as they suggest that it may take only a small bit of information to overcome misinformation.

So the next time you hear friends or co-workers refer to someone who’s acting strangely as “insane,” you may want to pipe up and correct them politely. It could make more of a difference than you think.

Myth #46 Virtually All People Who Confess to a Crime Are Guilty of It

We’ve all seen countless examples in the media of the “good-cop, bad-cop” game police play to extract confessions from criminal suspects. As the familiar routine goes, the “bad cop” confronts the suspect with overwhelming evidence of his guilt (it’s usually a “he”), points out discrepancies in his testimony, questions his alibi, and intimidates him with the prospect of a long jail term if he doesn’t confess. In contrast, the “good cop” offers sympathy and support, suggests possible justifica tions for the crime, and emphasizes the benefits of snitching on fellow criminals. As the scenario plays out, the suspect confesses to the crime, and there’s no doubt about his guilt.

The belief that virtually all people who confess to a crime are guilty of it is comforting. Perhaps one reason why this idea is so appealing is that the bad guys get off the streets, and law and order prevail. Case closed.

Crime fighters claim to be accurate in ferreting out guilty parties. In one survey of American police investigators and Canadian customs officials, 77% of participants believed they were accurate at detecting whether a suspect was guilty (Kassin et al., 2007). Much of the news and entertainment media assume that criminal confessions are invari ably accurate. Writing about the unsolved anthrax poisoning case that terrified much of America in late 2001, two New York Times reporters suggested that a confession on the part Dr. Bruce Ivins (a person pursued by the FBI who ending up committing suicide) would have provided “a definitive piece of evidence indisputably proving that Dr. Ivins mailed the letters” containing anthrax (Shane & Lichtblau, 2008, p. 24). The documentary film, Confessions of Crime (1991), regaled viewers with convicted killers’ confessions to crimes on videotape, with the inscription “fact not fiction” emblazoned in bold letters on the video box. The violence portrayed may be disturbing, but we can sleep easier knowing that the evildoers wind up in prisons. In another documentary, The Iceman—Confessions of a Mafia Hitman (2002), Richard Kuklinski described in graphic detail the multiple murders he perpetrated while undercover as a businessman and family man. Yes, danger lurks out there, but we can be reassured that Kuklinski is now behind bars.

Television and movies hammer home the message that the people who confess to their nefarious deeds are almost always the real culprits. Yet the actual state of affairs is much more disturbing, and much less tidy: People sometimes confess to crimes they didn’t commit. A case in point is John Mark Karr. In August 2006, Karr confessed to the 1996 murder of 6-year-old beauty queen JonBenet Ramsey. The Ramsey case captivated the media’s attention for a decade, so hopes were raised that the murder would finally be solved. But following a frenzy of stories fingering Karr as the killer, the media soon reported that Karr couldn’t have been the perpetrator because his DNA didn’t match what investigators had found at the crime scene. Speculation was rampant about why Karr confessed. Was Karr, an alleged pedophile who was admittedly fascinated and perhaps obsessed with JonBenet, delusional or merely a publicity hound? More broadly, why do people confess to crimes they didn’t commit?

We’ll return to this question soon, but for now, we should point out that false confessions aren’t uncommon in high-profile criminal cases. After world-famous aviator Charles Lindbergh’s son was kidnapped in 1932, more than 200 people confessed to the crime (Macdonald & Michaud, 1987). Clearly, they couldn’t all be guilty. In the late 1940s, the notorious “Black Dahlia” case—so named because Elizabeth Short, the aspiring actress who was murdered and mutilated, always dressed in black—inspired more than 30 people to confess to the crime. At least 29, and possibly all 30, of these confessions were false. To this day, Short’s murder remains unsolved (Macdonald & Michaud, 1987).

Because so many people falsely confess to high-profile crimes, invest igators keep the details of crime scenes from the media to weed out “false confessors.” Truly guilty parties should be able to provide accurate information about the crime scene withheld by police and thereby prove their guilt. Henry Lee Lucas, who “confessed” to more than 600 serial murderers, was possibly the most prolific of all false confessors. He has the distinction of being the only person whose death sentence future U.S. president George W. Bush commuted of the 153 on which he passed judgment while Governor of Texas. Although Lucas may have murdered one or more people, most authorities are justifiably skeptical of his wild claims. Gisli Gudjonsson (1992) conducted a comprehensive evaluation of Lucas, and concluded that he said and did things for immediate gain and attention, eager to please and impress people. Clearly, these sorts of motivations may be at play in confessions regarding many well-publicized murders like the JonBenet Ramsey and Black Dahlia crimes.

People may confess voluntarily to crimes they didn’t commit for a myriad of other reasons, including a need for self-punishment to “pay for” real or imagined past transgressions; a desire to protect the real perpetrator, such as a spouse or child; or because they find it difficult to distinguish fantasy from reality (Gudjonsson, 2003; Kassin & Gudjonsson, 2004). Unfortunately, when people come out of the woodwork to confess to crimes they didn’t commit, or exaggerate their involvements in actual criminal investigations, it may hinder police attempts to identify the real perpetrator.

But an even more serious concern about false confessions is that judges and jurors are likely to view them as persuasive evidence of guilt (Conti, 1999; Kassin, 1998; Wrightsman, Nietzel, & Fortune, 1994). According to statistics compiled by the Innocence Project (2008), in more than 25% of cases in which DNA evidence later exonerated convicted individuals, they made false confessions or pled guilty to crimes they didn’t commit. These findings are alarming enough, but the scope of the problem may be far greater because many false confessions are probably rejected as unfounded long before people get to trial because of suspected mental illness. Moreover, laboratory studies reveal that neither college students nor police officers are good at detecting when people falsely confess to prohibited or criminal activities (Kassin, Meissner, & Norwick, 2005; Lassiter, Clark, Daniels, & Soinski, 2004). In one study (Kassin et al., 2005), police were more confident in their ability to detect false con fessions than were college students, although the police were no more accurate. In a condition in which participants listened to audiotaped con fessions, police were more likely to believe that the false confessions were actually truthful. Thus, police may be biased to perceive people as guilty when they’re innocent.

The following cases further underscore the difficulties with false confessions, and exemplify different types of false confessions. Beyond voluntary confessions, Saul Kassin and his colleagues (Kassin, 1998; Kassin & Wrightsman, 1985; Wrightsman & Kassin, 1993) categorized false confessions as either compliant or internalized. In the compliant type, people confess during interrogation to gain a promised or implied reward, escape an unpleasant situation, or avoid a threat (Kassin & Gudjonsson, 2004). The case of the “Central Park Five,” in which five teenagers confessed to brutally beating and raping a jogger in New York City’s Central Park in 1989, provides a good example of a compliant confession. The teenagers later recanted their confession, saying they believed they could go home if they admitted their guilt. After spend ing 51/2 to 13 years in prison, they were released after DNA evidence exonerated them. In 2002, 13 years after the crime was perpetrated, a serial rapist confessed to the crime.

Now consider the case of Eddie Joe Lloyd. Lloyd had a history of mental problems and made a practice of calling the police with sugges tions about how to solve crimes. In 1984, a detective convinced him to confess to raping and murdering 16-year-old Michelle Jackson to trick the real rapist into revealing himself. Based on his confession, Lloyd was convicted and released 18 years later because his DNA didn’t match that of the real rapist (Wilgoren, 2002).

In internalized confessions, vulnerable people come to believe they actually committed a crime because of pressures brought to bear on them during an interrogation. Police have tremendous latitude in inter rogations and, at least in the U.S., can legally lie and distort informa tion to extract a confession. For example, they can legally play the role of “bad cop” and confront suspects with false information about their alleged guilt, challenge their alibis, undermine suspects’ confidence in their denials of criminal activity, and even falsely inform suspects that they’d failed a lie detector test (Leo, 1996).

Jorge Hernandez fell prey to such high-pressure techniques in the course of an investigation of the rape of a 94-year-old woman. Hernandez stated repeatedly that he couldn’t remember what he was doing on the night of the crime several months earlier. Police claimed not only that they found his fingerprints at the crime scene, but that they had surveillance footage placing him at the scene of the crime. Confronted with this false evidence and told that the police would help him if he confessed, Hernandez began to doubt his own memory, and concluded that he must have been drunk and couldn’t remember that he committed rape. Fortunately for Hernandez, after he spent 3 weeks in jail, he was released when authorities determined that his DNA didn’t match samples taken from the crime scene.

Research indicates that many people are vulnerable to false con fessions (Kassin & Kiechel, 1996). In an experiment supposedly con cerning reaction time, investigators led subjects to believe they were responsible for a computer crash that occurred because they had pressed a key the research assistant had instructed them to avoid. Actually, the researchers had rigged the computer to crash; no subject touched the “forbidden” key. When a supposed witness was present and the pace was fast, all subjects signed a confession afterward admitting their “guilt.” Moreover, 65% of these subjects internalized guilt, as indicated by their telling someone in a waiting room (actually a confederate) that they were responsible for the computer crash. When they returned to the lab to reconstruct what happened, 35% made up details consistent with their confession (such as “I hit the key with my right hand when you called out “A.”).

Researchers have identified personal and situational characteristics that increase the likelihood of false confessions. People who admit to crimes they didn’t commit are more likely to: (a) be relatively young (Medford, Gudjonnson, & Pearse, 2003), suggestible (Gudjonsson, 1992), and isolated from others (Kassin & Gudjonnson, 2004); (b) be confronted with strong evidence of their guilt (Moston, Stephenson, Williamson, 1992); (c) have a prior criminal history, use illicit drugs, and have no legal counsel (Pearse, Gudjonsson, Claire, & Rutter, 1998); and (d) be questioned by intimidating and manipulative interviewers (Gudjonsson, 2003).

Interestingly, the media may prove helpful in minimizing the risk of false confessions. Publicizing cases in which innocent people are wrongly imprisoned based on false confessions may spur efforts to create needed reforms in police interrogations, such as videotaping interviews from start to finish to evaluate the use and effects of coercive procedures. In fact, many police departments are already videotaping interrogations of suspects. We must “confess” we’d be pleased if this practice were implemented on a universal basis. And we stand by our confession.

Chapter 10: Other Myths to Explore

| Fiction | Fact |

| Rehabilitation programs have no effect on the recidivism rates of criminals | Reviews show that rehabilitation programs reduce the overall rate of criminal re-offending. |

| Most pedophiles (child abusers) have extremely high rates of recidivism. | The majority of pedophiles don’t reoffend within 15 years of their initial offense, or at least aren’t caught doing so. |

| All pedophiles are untreatable. | Reviews of treatment studies show modest positive effects on re-offending among pedophiles. |

| The best approach to treating delinquents is “getting tough” with them. | Controlled studies show that boot camp and “Scared Straight” interventions are ineffective, and even potentially harmful, for delinquents. |

| The overwhelming majority of acts of domestic violence are committed by men. | Men and women physically abuse each other at about equal rates, although more women suffer injuries as a result. |

| The rates of domestic abuse against women increase markedly on Super Bowl Sunday. | There’s no evidence for this widespread claim. |

| Being a postal worker is among the most dangerous of all occupations. | Being a postal worker is a safe occupation; the lifetime odds of being killed on the job are only 1 in 370,000 compared with 1 in 15,000 for farmers and 1 in 7,300 for construction workers. |

| Most psychopaths are violent. | Most psychopaths aren’t physically violent. |

| Most psychopaths are out of touch with reality. | Most psychopaths are entirely rational and aware that their actions are wrong, but they don’t care. |

| Psychopaths are untreatable. | Research provides little support for this claim; more recent evidence suggests that imprisoned psychopaths benefit from treatment as much as other psychiatric patients. |

| Serial killings are especially common among Whites. | The rates of serial killers are no higher among Whites than other racial groups. |

| Police officers have especially high rates of suicide. | Meta-analyses show that police officers aren’t more prone to suicide than other people. |

| There is an “addictive personality.” | No single personality “type” is at risk for addiction, although such traits as impulsivity and anxiety-proneness predict risk. |

| Alcoholism is uniquely associated with “denial.” | There’s little evidence that people with alcoholism are more likely to deny their problems than people with most other psychological disorders. |

| Most rapes are committed by strangers. | Rapes by strangers comprise only about 4% of all rapes. |

| Police psychics have proven useful in solving crimes. | Police psychics do no better than anyone else in helping to solve crimes. |

| Homicide is more common than suicide. | Suicide is about one third more common than homicide. |

| “Insanity” is a formal psychological and psychiatric term. | Insanity and sanity are purely legal terms typically referring to the inability (or ability) to distinguish right from wrong or to know what one was doing at the time of the act. |

| The legal determination of insanity is based on the person’s current mental state. | The legal determination of insanity is based on the person’s mental state at the time of the crime. |

| Most people who plead insanity are faking mental illness. | Only a minority of individuals who plead insanity obtain clinically elevated scores on measures of malingering. |

| The insanity verdict is a “rich person’s” defense. | Cases of extremely rich people who claim insanity with the support of high-priced attorneys are widely publicized but rare. |

Sources and Suggested Readings

To explore these and other myths about psychology and the law, see Aamodt (2008); Arkowitz and Lilienfeld (2008); Borgida and Fiske (2008); Edens (2006); Nickell (1994); Phillips, Wolf, and Coons (1988); Silver, Circincione, and Steadman (1994); Ropeik and Gray (2002); Skeem, Douglas, and Lilienfeld (2009).