INTRODUCTION

The Wide World of Psychomythology

“Opposites attract.”

“Spare the rod, spoil the child.”

“Familiarity breeds contempt.”

“There’s safety in numbers.”

You’ve probably heard these four proverbs many times before. More over, like our rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, you probably hold them to be self-evident. Our teachers and parents have assured us that these sayings are correct, and our intuitions and life experi ences confirm their wisdom.

Yet psychological research demonstrates that all four proverbs, as people commonly understand them, are mostly or entirely wrong. Opposites don’t attract in romantic relationships; to the contrary, we tend to be most attracted to people who are similar to us in our per sonalities, attitudes, and values (see Myth #27). Sparing the rod doesn’t necessarily spoil children; moreover, physical punishment often fails to produce positive effects on their behavior (see p. 97). Familiarity usu ally breeds comfort, not contempt; we usually prefer things we’ve seen many times to things that are novel (see p. 133). Finally, there’s typic ally danger rather than safety in numbers (see Myth #28); we’re more likely to be rescued in an emergency if only one bystander, rather than a large group of bystanders, is watching.

The Popular Psychology Industry

You’ve almost certainly “learned” a host of other “facts” from the popu lar psychology industry. This industry encompasses a sprawling network of sources of everyday information about human behavior, including television shows, radio call-in programs, Hollywood movies, self-help books, newsstand magazines, newspaper tabloids, and Internet sites. For example, the popular psychology industry tells us that:

- we use only 10% of our brain power;

- our memories work like videotapes or tape recorders;

- if we’re angry, it’s better to express the anger directly than hold it in;

- most sexually abused children grow up to become abusers themselves;

- people with schizophrenia have “split” personalities;

- people tend to act strangely during full moons.

Yet we’ll learn in this book that all six “facts” are actually fictions. Although the popular psychology industry can be an invaluable resource for information about human behavior, it contains at least as much mis information as information (Stanovich, 2007; Uttal, 2003). We term this vast body of misinformation psychomythology because it consists of mis conceptions, urban legends, and old wives’ tales regarding psychology. Surprisingly, few popular books devote more than a handful of pages to debunking psychomythology. Nor do more than a handful of popular sources provide readers with scientific thinking tools for distinguishing factual from fictional claims in popular psychology. As a consequence, many people—even students who graduate from college with majors in psychology—know a fair amount about what’s true regarding human behavior, but not much about what’s false (Chew, 2004; Della Sala, 1999, 2007; Herculano-Houzel, 2002; Lilienfeld, 2005b).

Before going much further, we should offer a few words of reassur ance. If you believed that all of the myths we presented were true, there’s no reason to feel ashamed, because you’re in awfully good company. Surveys reveal that many or most people in the general population (Furnham, Callahan, & Rawles, 2003; Wilson, Greene, & Loftus, 1986), as well as beginning psychology students (Brown, 1983; Chew, 2004; Gardner & Dalsing, 1986, Lamal, 1979; McCutcheon, 1991; Taylor & Kowalski, 2004; Vaughan, 1977), believe these and other psychological myths. Even some psychology professors believe them (Gardner & Hund, 1983).

If you’re still feeling a tad bit insecure about your “Psychology IQ,” you should know that the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 b.c.), who’s widely regarded as one of the smartest human beings ever to walk the face of the earth, believed that emotions originate from the heart, not the brain, and that women are less intelligent than men. He even believed that women have fewer teeth than men! Aristotle’s bloopers remind us that high intelligence offers no immunity against belief in psychomythology. Indeed, a central theme of this book is that we can all fall prey to erroneous psychological claims unless we’re armed with accurate knowledge. That’s as true today as it was in past centuries.

Indeed, for much of the 1800s, the psychological discipline of “phrenology” was all the rage throughout much of Europe and America (Greenblatt, 1995; Leahy & Leahy, 1983). Phrenologists believed that extremely specific psychological capacities, like poetic ability, love of chil dren, appreciation of colors, and religiosity, were localized to distinct brain regions, and that they could detect people’s personality traits by measuring the patterns of bumps on people’s skulls (they thought incorrectly that enlarged brain areas create indentations on the skull). The range of psychological capacities supposedly pinpointed by phrenologists ranged from 27 to 43. Phrenology “parlors” allowing curious patrons to have their skulls and personalities measured sprouted up in many locations, giving rise to the still popular phrase “having one’s head examined.” Yet phrenology turned out to be a striking example of psychomythology on a grand societal scale, as studies eventually showed that damage to the brain areas identified by phrenologists hardly ever caused the psychological deficits they’d so confidently predicted. Although phrenology— depicted on this book’s cover—is now dead, scores of other examples of psychomythology are alive and well.

In this book, we’ll help you to distinguish fact from fiction in popu lar psychology, and provide you with a set of mythbusting skills for evaluating psychological claims scientifically. We’ll not only shatter widespread myths about popular psychology, but explain what’s been found to be true in each domain of knowledge. We hope to persuade you that scientifically supported claims regarding human behavior are every bit as interesting as—and often even more surprising than—the mistaken claims.

That’s not to say that we should dismiss everything the popular psy chology industry tells us. Many self-help books encourage us to take responsibility for our mistakes rather than to blame others for them, offer a warm and nurturing environment for our children, eat in moderation and exercise regularly, and rely on friends and other sources of social support when we’re feeling down. By and large, these are wise tidbits of advice, even if our grandmothers knew about them.

The problem is that the popular psychology industry often intersperses such advice with suggestions that fly in the face of scientific evidence (Stanovich, 2007; Wade, 2008; Williams & Ceci, 1998). For example, some popular talk-show psychologists urge us to always “follow our heart” in romantic relationships, even though this advice can lead us to make poor interpersonal decisions (Wilson, 2003). The popular television psychologist, Dr. Phil McGraw (“Dr. Phil”), has promoted the polygraph or so-called “lie detector” test on his television program as means of finding out which partner in a relationship is lying (Levenson, 2005). Yet as we’ll learn later (see Myth #23), scientific research demonstrates that the polygraph test is anything but an infallible detector of the truth (Lykken, 1998; Ruscio, 2005).

Armchair Psychology

As personality theorist George Kelly (1955) pointed out, we’re all arm chair psychologists. We continually seek to understand what makes our friends, family members, lovers, and strangers tick, and we strive to understand why they do what they do. Moreover, psychology is an inescapable part of our everyday lives. Whether it’s our romantic relation ships, friendships, memory lapses, emotional outbursts, sleep problems, performance on tests, or adjustment difficulties, psychology is all around us. The popular press bombards us on an almost daily basis with claims regarding brain development, parenting, education, sexuality, intelligence testing, memory, crime, drug use, mental disorders, psychotherapy, and a bewildering array of other topics. In most cases we’re forced to accept these claims on faith alone, because we haven’t acquired the scientific thinking skills to evaluate them. As neuroscience mythbuster Sergio Della Sala (1999) reminded us, “believers’ books abound and they sell like hot cakes” (p. xiv).

That’s a shame, because although some popular psychology claims are well supported, scores of others aren’t (Furnham, 1996). Indeed, much of everyday psychology consists of what psychologist Paul Meehl (1993) called “fireside inductions”: assumptions about behavior based solely on our intuitions. The history of psychology teaches us one undeniable fact: Although our intuitions can be immensely useful for generating hypotheses to be tested using rigorous research methods, they’re often woefully flawed as a means of determining whether these hypotheses are correct (Myers, 2002; Stanovich, 2007). To a large extent, that’s probably because the human brain evolved to understand the world around it, not to understand itself, a dilemma that science writer Jacob Bronowski (1966) called “reflexivity.” Making matters worse, we often cook up reasonable-sounding, but false, explanations for our behaviors after the fact (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). As a consequence, we can per suade ourselves that we understand the causes of our behaviors even when we don’t.

Psychological Science and Common Sense

One reason we’re easily seduced by psychomythology is that it jibes with our common sense: our gut hunches, intuitions, and first impressions. Indeed, you may have heard that most psychology is “just common sense” (Furnham, 1983; Houston, 1985; Murphy, 1990). Many prominent authorities agree, urging us to trust our common sense when it comes to evaluating claims. Popular radio talk show host Dennis Prager is fond of informing his listeners that “There are two kinds of studies in the world: those that confirm our common sense and those that are wrong.” Prager’s views regarding common sense are probably shared by many members of the general public:

Use your common sense. Whenever you hear the words “studies show”— outside of the natural sciences—and you find that these studies show the opposite of what common sense suggests, be very skeptical. I do not recall ever coming across a valid study that contravened common sense. (Prager, 2002, p. 1)

For centuries, many prominent philosophers, scientists, and science writers have urged us to trust our common sense (Furnham, 1996; Gendreau, Goggin, Cullen, & Paparozzi, 2002). The 18th century Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid argued that we’re all born with common sense intuitions, and that these intuitions are the best means of arriving at funda mental truths about the world. More recently, in a New York Times editorial, well-known science writer John Horgan (2005) called for a return to common sense in the evaluation of scientific theories, including those in psychology. For Horgan, far too many theories in physics and other areas of modern science contradict common sense, a trend he finds deeply worrisome. In addition, the last several years have witnessed a proliferation of popular and even bestselling books that champion the power of intuition and snap judgments (Gigerenzer, 2007; Gladwell, 2005). Most of these books acknowledge the limitations of common sense in evaluating the truth of scientific claims, but contend that psychologists have traditionally underestimated the accuracy of our hunches.

Yet as the French writer Voltaire (1764) pointed out, “Common sense is not so common.” Contrary to Dennis Prager, psychological studies that overturn our common sense are sometimes right. Indeed, one of our primary goals in this book is to encourage you to mistrust your com mon sense when evaluating psychological claims. As a general rule, you should consult research evidence, not your intuitions, when deciding whether a scientific claim is correct. Research suggests that snap judgments are often helpful in sizing up people and in forecasting our likes and dislikes (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1992; Lehrer, 2009; Wilson, 2004), but they can be wildly inaccurate when it comes to gauging the accuracy of psychological theories or assertions. We’ll soon see why.

As several science writers, including Lewis Wolpert (1992) and Alan Cromer (1993), have observed, science is uncommon sense. In other words, science requires us to put aside our common sense when evaluating evid ence (Flagel & Gendreau, 2008; Gendreau et al., 2002). To understand science, including psychological science, we must heed the advice of the great American humorist Mark Twain, namely, that we need to unlearn old habits of thinking at least as much as learn new ones. In particular, we need to unlearn a tendency that comes naturally to all of us—the tendency to assume that our gut hunches are correct (Beins, 2008).

Of course, not all popular psychology wisdom, sometimes called “folk psychology,” is wrong. Most people believe that happy employees get more work done on the job than unhappy employees, and psychological research demonstrates that they’re right (Kluger & Tikochinsky, 2001). Yet time and time again, scientists—including psychological scientists— have discovered that we can’t always trust our common sense (Cacioppo, 2004; Della Sala, 1999, 2007; Gendreau et al., 2002; Osberg, 1991; Uttal, 2003). In part, that’s because our raw perceptions can deceive us.

For example, for many centuries, humans assumed not only that the earth is flat—after all, it sure seems flat when we’re walking on it—but that the sun revolves around the earth. This latter “fact” in particular seemed obvious to virtually everyone. After all, each day the sun paints a huge arc across the sky while we remain planted firmly on the ground. But in this case, observers’ eyes fooled them. As science historian Daniel Boorstin (1983) noted:

Nothing could be more obvious than that the earth is stable and unmov-ing, and that we are the center of the universe. Modern Western science takes its beginning from the denial of this commonsense axiom … Common sense, the foundation of everyday life, could no longer serve for the governance of the world. (p. 294)

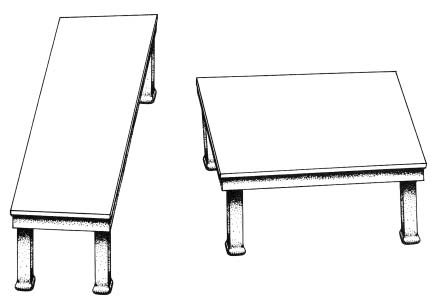

Figure I.1 A diagram from the study by Michael McCloskey (1983). What path will the ball take after exiting the spiral?

Source: McCloskey (1983).

Let’s consider another example. In Figure I.1, you’ll see a drawing from a study from the work of Michael McCloskey (1983), who asked college students to predict the path of a ball that has just exited from an enclosed spiral. About half of the undergraduates predicted incorrectly that the ball would continue to travel in a spiral path after exiting, as shown on the right side of the figure (in fact, the ball will travel in a straight path after exiting, as shown on the left side of the figure). These students typic ally invoked commonsense notions like “momentum” when justifying their answers (for example, “The ball started traveling in a certain way, so it will just keep going that way”). By doing so, they seemed almost to treat the ball as a person, much like a figure skater who starts spinning on the ice and keeps on spinning. In this case, their intuitions betrayed them.

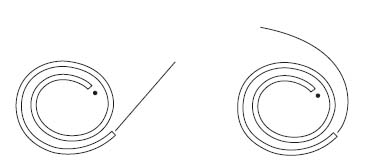

We can see another delightful example in Figure I.2, which displays “Shepard’s tables,” courtesy of cognitive psychologist Roger Shepard (1990). Take a careful look at the two tables in this figure and ask your self which table top contains a larger surface area. The answer seems obvious at first glance.

Yet believe it or not, the surfaces of both tables are identical (if you don’t believe us, photocopy this page, cut out the figures, and super impose them on each other). Just as we shouldn’t always trust our eyes, we shouldn’t always trust our intuitions. The bottom line: Seeing is believing, but seeing isn’t always believing correctly.

Shephard’s tables provide us with a powerful optical illusion—an image that tricks our visual system. In the remainder of this book, though, we’ll be crossing paths with a variety of cognitive illusions—beliefs that trick our reasoning processes (Pohl, 2004). We can think of many or most psychological myths as cognitive illusions, because like visual illusions they can fool us.

Why Should We Care?

Why is it important to know about psychological myths? There are at least three reasons:

(1) Psychological myths can be harmful. For example, jurors who believe incorrectly that memory operates like a videotape may vote to convict a defendant on the basis of confidently held, but inaccurate, eyewitness testimony (see Myth #11). In addition, parents who believe incorrectly that punishment is usually an effective means of changing long-term behavior may spank their children whenever they misbehave, only to find that their children’s undesirable actions become more frequent over time (see p. 97).

(2) Psychological myths can cause indirect damage. Even false beliefs that are themselves harmless can inflict significant indirect harm. Economists use the term opportunity cost to refer to the fact that people who seek out ineffective treatments may forfeit the chance to obtain much-needed help. For example, people who believe mistakenly that subliminal self-help tapes are an effective means of losing weight may invest a great deal of time, money, and effort on a useless intervention (Moore, 1992; see Myth #5). They may also miss out on scientifically based weight loss programs that could prove beneficial.

(3) The acceptance of psychological myths can impede our critical think ing in other areas. As astronomer Carl Sagan (1995) noted, our failure to distinguish myth from reality in one domain of scientific knowledge, such as psychology, can easily spill over to a failure to distinguish fact from fiction in other vitally important areas of modern society. These domains include genetic engineering, stem cell research, global warming, pollution, crime prevention, school ing, day care, and overpopulation, to name merely a few. As a consequence, we may find ourselves at the mercy of policy-makers who make unwise and even dangerous decisions about science and technology. As Sir Francis Bacon reminded us, knowledge is power. Ignorance is powerlessness.

The 10 Sources of Psychological Myths: Your Mythbusting Kit

How do psychological myths and misconceptions arise?

We’ll try to persuade you that there are 10 major ways in which we can all be fooled by plausible-sounding, but false, psychological claims. It’s essential to understand that we’re all vulnerable to these 10 sources of error, and that we’re all fooled by them from time to time.

Learning to think scientifically requires us to become aware of these sources of error and learn to compensate for them. Good scientists are just as prone to these sources of error as the average person (Mahoney & DeMonbreun, 1977). But good scientists have adopted a set of safeguards—called the scientific method—for protecting themselves against them. The scientific method is a toolbox of skills designed to prevent scientists from fooling themselves. If you become aware of the 10 major sources of psychomythology, you’ll be far less likely to fall into the trap of accepting erroneous claims regarding human nature.

Pay careful attention to these 10 sources of error, because we’ll come back to them periodically throughout the book. In addition, you’ll be able to use these sources of error to evaluate a host of folk psychology claims in your everyday life. Think of them as your lifelong “Mythbust-ing Kit.”

(1) Word-of-Mouth

Many incorrect folk psychology beliefs are spread across multiple generations by verbal communication. For example, because the phrase “opposites attract” is catchy and easily remembered, people tend to pass it on to others. Many urban legends work the same way. For example, you may have heard the story about alligators living in the New York City sewer system or about the well-intentioned but foolish woman who placed her wet poodle in a microwave to dry it off, only to have it explode. For many years, the first author of this book relayed a story he’d heard many times, namely the tale of a woman who purchased what she believed was a pet Chihuahua, only to be informed weeks later by a veterinarian that it was actually a gigantic rat. Although these stories may make for juicy dinner table conversation, they’re no truer than any of the psychological myths we’ll present in this book (Brunvand, 1999).

The fact that we’ve heard a claim repeated over and over again doesn’t make it correct. But it can lead us to accept this claim as correct even when it’s not, because we can confuse a statement’s familiarity with its accuracy (Gigerenzer, 2007). Advertisers who tell us repeatedly that “Seven of eight dentists surveyed recommended Brightshine Toothpaste above all over brands!” capitalize on this principle mercilessly. Furthermore, research shows that hearing one person express an opinion (“Joe Smith is the best qualified person to be President!”) 10 times can lead us to assume that this opinion is as widely held as hearing 10 people express this opinion once (Weaver, Garcia, Schwarz, & Miller, 2007). Hearing is often believing, especially when we hear a statement over and over again.

(2) Desire for Easy Answers and Quick Fixes

Let’s face it: Everyday life isn’t easy, even for the best adjusted of us. Many of us struggle to find ways to lose weight, get enough sleep, per form well on exams, enjoy our jobs, and find a lifelong romantic partner. It’s hardly a surprise that we glom on to techniques that offer foolproof promises of rapid and painless behavior changes. For example, fad diets are immensely popular, even though research demonstrates that the sub stantial majority of people who go on them regain all of their weight within just a few years (Brownell & Rodin, 1994). Equally popular are speed reading courses, many of which promise to increase people’s reading speeds from a mere 100 or 200 words per minute to 10,000 or even 25,000 words per minute (Carroll, 2003). Yet researchers have found that none of these courses boost people’s reading speeds with out decreasing their reading comprehension (Carver, 1987). What’s more, most of the reading speeds advertised by these courses exceed the maximum reading speed of the human eyeball, which is about 300 words per minute (Carroll, 2003). A word to the wise: If something sounds too good to be true, it probably is (Sagan, 1995).

(3) Selective Perception and Memory

As we’ve already discovered, we rarely if ever perceive reality exactly as it is. We see it through our own set of distorting lenses. These lenses are warped by our biases and expectations, which lead us to interpret the world in accord with our preexisting beliefs. Yet most of us are blissfully unaware of how these beliefs influence our perceptions. Psychologist Lee Ross and others have termed the mistaken assumption that we see the world precisely as it is naïve realism (Ross & Ward, 1996). Naïve realism not only leaves us vulnerable to psychological myths, but renders us less capable of recognizing them as myths in the first place.

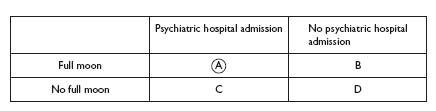

A striking example of selective perception and memory is our tendency to focus on “hits”—memorable co-occurrences—rather than on “misses” —the absence of memorable co-occurrences. To understand this point, take a look at Figure I.3, where you’ll see what we call “The Great Fourfold Table of Life.” Many scenarios in everyday life can be arranged in a fourfold table like the one here. For example, let’s investigate the question of whether full moons are associated with more admissions to psychiatric hospitals, as emergency room physicians and nurses commonly claim (see Myth #42). To answer this question, we need to examine all four cells of the Great Fourfold Table of Life: Cell A, which consists of instances when there’s a full moon and a psychiatric hospital admission, Cell B, which consists of instances when there’s a full moon but no psychiatric hospital admission, Cell C, which consists of instances when there’s no full moon and a psychiatric hospital admis sion, and Cell D, which consists of instances when there’s no full moon and no psychiatric hospital admission. Using all four cells allows you to compute the correlation between full moons and the number of psychiatric hospital admissions; a correlation is a statistical measure of how closely these two variables are associated (by the way, a variable is a fancy term for anything that varies, like height, hair color, IQ, or extraversion).

Figure I.3 The Great Fourfold Table of Life. In most cases, we attend too much to the A cell, which can result in illusory correlation.

Here’s the problem. In real life, we’re often remarkably poor at estimating correlations from the Great Fourfold Table of Life, because we generally pay too much attention to certain cells and not enough to others. In particular, research demonstrates that we typically pay too much attention to the A cell, and not nearly enough to the B cell (Gilovich, 1991). That’s understandable, because the A cell is usually more inter esting and memorable than the B cell. After all, when there’s a full moon and a lot of people end up in a psychiatric hospital, it confirms our initial expectations, so we tend to notice it, remember it, and tell others about it. The A cell is a “hit”—a striking co-occurrence. But when there’s a full moon and nobody ends up in a psychiatric hospital, we barely notice or remember this “nonevent.” Nor are we likely to run excitedly to our friends and tell them, “Wow, there was a full moon tonight and guess what happened? Nothing!” The B cell is a “miss”— the absence of a striking co-occurrence.

Our tendency to remember our hits and forget our misses often leads to a remarkable phenomenon called illusory correlation, the mistaken perception that two statistically unrelated events are actually related (Chapman & Chapman, 1967). The supposed relation between full moons and psychiatric hospital admissions is a stunning example of an illusory correlation. Although many people are convinced that this correlation exists, research demonstrates that it doesn’t (Rotton & Kelly, 1985; see Myth #42). The belief in the full moon effect is a cognitive illusion.

Illusory correlations can lead us to “see” a variety of associations that aren’t there. For example, many people with arthritis insist that their joints hurt more in rainy than in non-rainy weather. Yet studies demon strate that this association is a figment of their imaginations (Quick, 1999). Presumably, people with arthritis attend too much to the A cell of the Great Fourfold Table of Life—instances when it rains and when their joints hurt—leading them to perceive a correlation that doesn’t exist. Similarly, the early phrenologists “saw” close linkages between damage to specific brain areas and deficits in certain psychological abilities, but they were wildly wrong.

Another probable example of illusory correlation is the perception that cases of infantile autism, a severe psychiatric disorder marked by severe language and social deficits, are associated with prior exposure to mercury-based vaccines (see Myth #41). Numerous carefully conducted studies have found no association whatsoever between the incidence of infantile autism and mercury vaccine exposure (Grinker, 2007; Institute of Medicine, 2004; Lilienfeld & Arkowitz, 2007), although tens of thousands of parents of autistic children are convinced otherwise. In all probability, these parents are paying too much attention to the A cell of the fourfold table. They can hardly be blamed for doing so given that they’re understandably trying to detect an event, such as a vaccination, that could explain their children’s autism. Moreover, these parents may have been fooled by the fact that the initial appearance of autistic symptoms—often shortly after age 2—often coincides with at the age when most children receive vaccinations.

(4) Inferring Causation from Correlation

It’s tempting, but incorrect, to conclude that if two things co-occur statistically (that is, if two things are “correlated”) then they must be causally related to each other. As psychologists like to say, correlation doesn’t mean causation. So, if variables A and B are correlated, there can be three major explanations for this correlation: (a) A may cause B, (b) B may cause A, or (c) a third variable, C, may cause both A and B. This last scenario is known as the third variable problem, because C is a third variable that may contribute to the association between variables A and C. The problem is that the researchers who conducted the study may never have measured C; in fact, they may have never known about C’s existence.

Let’s take a concrete example. Numerous studies demonstrate that a history of physical abuse in childhood increases one’s odds of becom ing an aggressive person in adulthood (Widom, 1989). Many investigators have interpreted this statistical association as implying that childhood physical abuse causes physical aggression in later life; indeed, this inter pretation is called the “cycle of violence” hypothesis. In this case, the investigators are assuming that childhood physical abuse (A) causes adult violence (B). Is this explanation necessarily right?

Of course, in this case B can’t cause A, because B occurred after A. A basic principle of logic is that causes must precede their effects. Yet we haven’t ruled out the possibility that a third variable, C, explains both A and B. One potential third variable in this case is a genetic tendency toward aggressiveness. Perhaps most parents who physically abuse their children harbor a genetic tendency toward aggressiveness, which they pass on to their children. Indeed, there’s good research evidence that aggressiveness is partly influenced by genes (Krueger, Hicks, & McGue, 2001). This genetic tendency (C) could result in a correlation between a childhood physical abuse history (A) and later aggression in individuals with this history (B), even though A and B may be causally unrelated to each other (DiLalla & Gottesman, 1991). Incidentally, there are other potential candidates for C in this case (can you think of any?).

The key point is that when two variables are correlated, we shouldn’t necessarily assume a direct causal relationship between them. Competing explanations are possible.

(5) Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc Reasoning

“Post hoc, ergo propter hoc” means “after this, therefore because of this” in Latin. Many of us leap to the conclusion that because A precedes B, then A must cause B. But many events that occur before other events don’t cause them. For example, the fact that virtually all serial killers ate cereal as children doesn’t mean that eating cereal produces serial killers (or even “cereal killers”—we couldn’t resist the pun) in adulthood. Or the fact that some people become less depressed soon after taking an herbal remedy doesn’t mean that the herbal remedy caused or even contributed to their improvement. These people might have become less depressed even without the herbal remedy, or they might have sought out other effective interventions (like talking to a therapist or even to a supportive friend) at about the same time. Or perhaps taking the herbal remedy inspired a sense of hope in them, resulting in what psychologists call a placebo effect: improvement resulting from the mere expectation of improvement.

Even trained scientists can fall prey to post hoc, ergo propter hoc reasoning. In the journal Medical Hypotheses, Flensmark (2004) observed that the appearance of shoes in the Western world about 1,000 years ago was soon followed by the first appearance of cases of schizo phrenia. From these findings, he proposed that shoes play a role in triggering schizophrenia. But the appearance of shoes could have merely coincided with other changes, such as the growth of modernization or an increase in stressful living conditions, which may have contributed more directly to the emergence of schizophrenia.

(6) Exposure to a Biased Sample

In the media and many aspects of daily life, we’re often exposed to a nonrandom—or what psychologists called a “biased”—sample of people from the general population. For example, television programs portray approximately 75% of severely mentally ill individuals as violent (Wahl, 1997), although the actual rate of violence among the severely mentally ill is considerably lower than that (Teplin, 1985; see Myth #43). Such skewed media coverage may fuel the erroneous impression that most indi viduals with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder (once called manic depres sion), and other serious mental illnesses are physically dangerous.

Psychotherapists may be especially prone to this error, because they spend most of their working lives with an unrepresentative group of indi viduals, namely, people in psychological treatment. Here’s an example: Many psychotherapists believe it’s exceedingly difficult for people to quit smoking on their own. Yet research demonstrates that many, if not most, smokers manage to stop without formal psychological treatment (Schachter, 1982). These psychotherapists are probably falling prey to what statisticians Patricia and Jacob Cohen (1984) termed the clinician’s illusion—the tendency for practitioners to overestimate how chronic (long standing) a psychological problem is because of their selective exposure to a chronic sample. That is, because clinicians who treat cigarette smokers tend to see only those individuals who can’t stop smoking on their own—otherwise, these smokers presumably wouldn’t have sought out a clinician in the first place—these clinicians tend to overestimate how difficult smokers find it to quit without treatment.

(7) Reasoning by Representativeness

We often evaluate the similarity between two things on the basis of their superficial resemblance to each other. Psychologists call this phenomenon the representativeness heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974), because we use the extent to which two things are “represent ative” of each other to estimate how similar they are. A “heuristic,” by the way, is a mental shortcut or rule of thumb.

Most of the time, the representativeness heuristic, like other heuristics, serves us well (Gigerenzer, 2007). If we’re walking down the street and see a masked man running out of a bank with a gun, we’ll probably try to get out of the way as quickly as we can. That’s because this man is representative of—similar to—bank robbers we’ve seen on television and in motion pictures. Of course, it’s possible that he’s just pulling a prank or that he’s an actor in a Hollywood action movie being filmed there, but better safe than sorry. In this case, we relied on a mental shortcut, and we were probably smart to do so.

Yet we sometimes apply the representativeness heuristic when we shouldn’t. Not all things that resemble each other superficially are related to each other, so the representativeness heuristic sometimes leads us astray (Gilovich & Savitsky, 1996). In this case, common sense is correct: We can’t always judge a book by its cover. Indeed, many psychological myths probably arise from a misapplication of representativeness. For example, some graphologists (handwriting analysts) claim that people whose handwriting contains many widely spaced letters possess strong needs for interpersonal distance, or that people who cross their “t”s and “f”s with whip-like lines tend to be sadistic. In this case, graphologists are assuming that two things that superficially resemble each other, like widely spaced letters and a need for interpersonal space, are statistically associated. Yet there’s not a shred of research support for these claims (Beyerstein & Beyerstein, 1992; see Myth #36).

Another example comes from human figure drawings, which many clinical psychologists use to detect respondents’ personality traits and psychological disorders (Watkins, Campbell, Nieberding, & Hallmark, 1995). Human figure drawing tasks, like the ever popular Draw-A-Person Test, ask people to draw a person (or in some cases, two persons of opposite sexes) in any way they wish. Some clinicians who use these tests claim that respondents who draw people with large eyes are paranoid, that respondents who draw people with large heads are narcissistic (self-centered), and even that respondents who draw people with long ties are excessively preoccupied with sex (a long tie is a favorite Freudian symbol for the male sexual organ). All these claims are based on a surface resemblance between specific human figure drawing “signs” and specific psychological characteristics. Yet research offers no support for these supposed associations (Lilienfeld, Wood, & Garb, 2000; Motta, Little, & Tobin, 1993).

(8) Misleading Film and Media Portrayals

Many psychological phenomena, especially mental illnesses and treatments for them, are frequently portrayed inaccurately in the entertainment and news media (Beins, 2008). More often than not, the media depicts these phenomena as more sensational than they are. For example, some modern films picture electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), known informally as “shock therapy,” as a physically brutal and even dangerous treatment (Walter & McDonald, 2004). In some cases, as in the 1999 horror film, House on Haunted Hill, individuals who’re strapped to ECT machines in movies experience violent convulsions. Although it’s true that that ECT was once somewhat dangerous, technological advances over the past few decades, such as the administration of a muscle relaxant, have rendered it no more physically hazardous than anesthesia (Glass, 2001; see Myth #50). Moreover, patients who receive modern forms of ECT don’t experience observable motor convulsions.

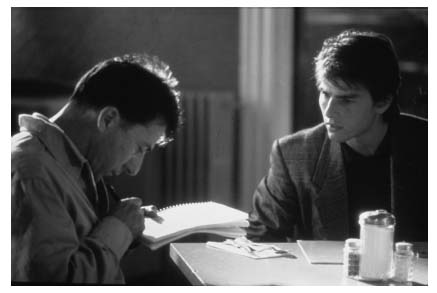

To take another example, most Hollywood films depict adults with autism as possessing highly specialized intellectual skills. In the 1988 Academy Award-winning film, Rain Main, Dustin Hoffman portrayed an autistic adult with “savant syndrome.” This syndrome is charac terized by remarkable mental abilities, such as “calendar calculation” (the ability to name the day of a week given any year and date), multiplication and division of extremely large numbers, and knowledge of trivia, such as the batting averages of all active major league baseball players. Yet at most 10% of autistic adults are savants (Miller, 1999; see Myth #41) (Figure I.4).

(9) Exaggeration of a Kernel of Truth

Some psychological myths aren’t entirely false. Instead, they’re exaggera tions of claims that contain a kernel of truth. For example, it’s almost certainly true that many of us don’t realize our full intellectual potential. Yet this fact doesn’t mean that most of us use only 10% of our brain power, as many people incorrectly believe (Beyerstein, 1999; Della Sala, 1999; see Myth #1). In addition, it’s probably true that at least a few differences in interests and personality traits between romantic partners can “spice up” a relationship. That’s because sharing your life with someone who agrees with you on everything can make your love life harmonious, but hopelessly boring. Yet this fact doesn’t imply that opposites attract (see Myth #27). Still other myths involve an overstate ment of small differences. For example, although men and women tend to differ slightly in their communication styles, some popular psy chologists, especially John Gray, have taken this kernel of truth to an extreme, claiming that “men are from Mars” and “women are from Venus” (see Myth #29).

Figure I.4 Film portrayals of individuals with autistic disorder, like this Academy Award-winning portrayal by actor Dustin Hoffman (left) in the 1988 film Rain Man, often imply that they possess remarkable intellectual capacities. Yet only about 10% of autistic individuals are savants.

Source: Photos 12/Alamy

(10) Terminological Confusion

Some psychological terms lend themselves to mistaken inferences. For example, the word “schizophrenia,” which Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler (1911) coined in the early 20th century, literally means “split mind.” As a consequence, many people believe incorrectly that people with schizo phrenia possess more than one personality (see Myth #39). Indeed, we’ll frequently hear the term “schizophrenic” in everyday language to refer to instances in which a person is of two different minds about an issue (“I’m feeling very schizophrenic about my girlfriend; I’m attracted to her physically but bothered by her personality quirks”). It’s therefore hardly surprising that many people confuse schizophrenia with an entirely dif ferent condition called “multiple personality disorder” (known today as “dissociative identity disorder”), which is supposedly characterized by the presence of more than one personality within the same individual (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In fact, schizophrenics possess only one personality that’s been shattered. Indeed, Bleuler (1911) intended the term “schizophrenia” to refer to the fact that individuals with this condition suffer from a splitting of mental functions, such as thinking and emotion, whereby their thoughts don’t correspond to their feelings. Nevertheless, in the world of popular psychology, Bleuler’s original and more accurate meaning has largely been lost. The misleading stereotype of schizophrenics as persons who act like two completely different people on different occasions has become ingrained in modern culture.

To take another example, the term “hypnosis” derives from the Greek prefix “hypno,” which means sleep (indeed, some early hypnotists believed that hypnosis was a form of sleep). This term may have led many people, including some psychologists, to assume that hypnosis is a sleep-like state. In films, hypnotists often attempt to induce a hypnotic state by telling their clients that “You’re getting sleepy.” Yet in fact, hypnosis bears no physiological relationship to sleep, because people who are hypnotized remain entirely awake and fully aware of their surroundings (Nash, 2001; see Myth #19).

The World of Psychomythology: What Lies Ahead

In this book, you’ll encounter 50 myths that are commonplace in the world of popular psychology. These myths span much of the broad landscape of modern psychology: brain functioning, perception, development, memory, intelligence, learning, altered states of consciousness, emotion, interpersonal behavior, personality, mental illness, the courtroom, and psychotherapy. You’ll learn about the psychological and societal origins of each myth, discover how each myth has shaped society’s popular thinking about human behavior, and find out what scientific research has to say about each myth. At the end of each chapter, we’ll provide you with a list of additional psychological myths to explore in each domain. In the book’s postscript, we’ll offer a list of fascinating findings that may appear to be fictional, but that are actually factual, to remind you that genuine psychology is often even more remarkable—and difficult to believe—than psychomythology.

Debunking myths comes with its share of risks (Chew, 2004; Landau & Bavaria, 2003). Psychologist Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues (Schwarz, Sanna, Skurnik, & Yoon, 2007; Skurnik, Yoon, Park, & Schwarz, 2005) showed that correcting a misconception, such as “The side effects of a flu vaccine are often worse than the flu itself,” can sometimes backfire by leading people to be more likely to believe this misconception later. That’s because people often remember the statement itself but not its “negation tag”—that is, the little yellow sticky note in our heads that says “that claim is wrong.” Schwarz’s work reminds us that merely memorizing a list of misconceptions isn’t enough: It’s crucial to understand the reasons underlying each misconception. His work also suggests that it’s essential for us to understand not merely what’s false, but also what’s true. Linking up a misconception with the truth is the best means of debunking that misconception (Schwarz et al., 2007). That’s why we’ll spend a few pages explaining not only why each of these 50 myths is wrong, but also how each of these 50 myths imparts an underlying truth about psychology.

Fortunately, there’s at least some reason to be optimistic. Research shows that psychology students’ acceptance of psychological miscon ceptions, like “people use only 10% of their brain’s capacity,” declines with the total number of psychology classes they’ve taken (Standing & Huber, 2003). This same study also showed that acceptance of these misconceptions is lower among psychology majors than non-majors. Although such research is only correlational—we’ve already learned that correlation doesn’t always mean causation—it gives us at least a glimmer of hope that education can reduce people’s beliefs in psychomythology. What’s more, recent controlled research suggests that explicitly refuting psychological misconceptions in introductory psychology lectures or readings can lead to large—up to 53.7%—decreases in the levels of these misconceptions (Kowalski & Taylor, in press).

If we’ve succeeded in our mission, you should emerge from this book not only with a higher “Psychology IQ,” but also a better understand ing of how to distinguish fact from fiction in popular psychology. Per haps most important, you should emerge with the critical thinking tools needed to better evaluate psychological claims in everyday life.

As the paleontologist and science writer Stephen Jay Gould (1996) pointed out, “the most erroneous stories are those we think we know best—and therefore never scrutinize or question” (p. 57). In this book, we’ll encourage you to never accept psychological stories on faith alone, and to always scrutinize and question the psychological stories you think you know best.

So without further ado, let’s enter the surprising and often fascinating world of psychomythology.