From the reign of Henry VIII England swung from Catholicism to Protestantism and back to Catholicism. The Act of Supremacy of 1558 re-established the Church of England’s independence from Rome, while the Act of Uniformity (passed the following year) set the English Book of Common Prayer at the heart of church services and made it a requirement that everyone had to go to church once a week or face a fine. The Church of England had broken away from the authority of the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church.

John Wesley, the theologian who founded the evangelical movement known as Methodism, preaching outside a church.

The term ‘Nonconformist’ derives from just over a century later when more than 2,000 clergymen refused to take the oath after a new Act of Uniformity set out forms of prayers, sacraments and other Church of England rites. This became known as the Great Ejection and created the concept of Nonconformity – the Protestant Christian who did not ‘conform’. Some Nonconformists were viewed as radical separatists, as dissenters, and for many years they were restricted from many spheres of public life. Though Catholics and Jews were Nonconformists, the word is normally used to describe Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Quakers and Methodists, among others.

The Presbyterian Church of Scotland has been recognised as the national church of Scotland since 1690. Although the relationship between Church and State in Scotland is not the same as in England, ‘Nonconformist’ is still used to describe churches that are not part of the Church of Scotland, such as Baptist, Methodist or Catholic. In Scotland, before 1834, Nonconformist ministers could not legally perform marriages as clergymen. After 1834 they could, but only if the banns had first been read in the parish church. Total authority was granted in 1855.

There are pockets and patterns in the distribution of Nonconformist churches. During the mid-seventeenth century the main areas of Quakerism, for example, were Westmorland, Cumberland, north Lancashire, Durham and Yorkshire. Wales, in particular, was dominated by the Methodist Church.

The London Metropolitan Archives has one of the largest collections relating to the history of the Anglo-Jewish community in Britain. These include records of organisations that helped individuals such as the Jewish Temporary Shelter and the Jews Free School. Staying in the capital, Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives has records of a number of Nonconformist churches, including material relating to St George’s German Lutheran Church (records of which have been comprehensively indexed by the Anglo-German Family History Society). St George’s German Lutheran Church, in Alie Street, Whitechapel, is the oldest surviving German Lutheran church in the UK, founded in 1762 by Dietrich Beckman, a wealthy sugar refiner. This area became home to many sugar refiners of German descent and at its height there were an estimated 16,000 German Lutherans in Whitechapel.

Historically, many Nonconformists used their local parish church for registration purposes (even after the Toleration Act of 1689 granted the freedom to worship), but also kept their own registers, particularly for births, baptisms and burials. Between 1754 and 1837 it was illegal to marry anywhere except in a Church of England parish church, unless you were a member of the Society of Friends (Quakers) or Jewish. And after 1837, while people were now allowed to marry in the church of their choice, some organisations still did not keep their own records.

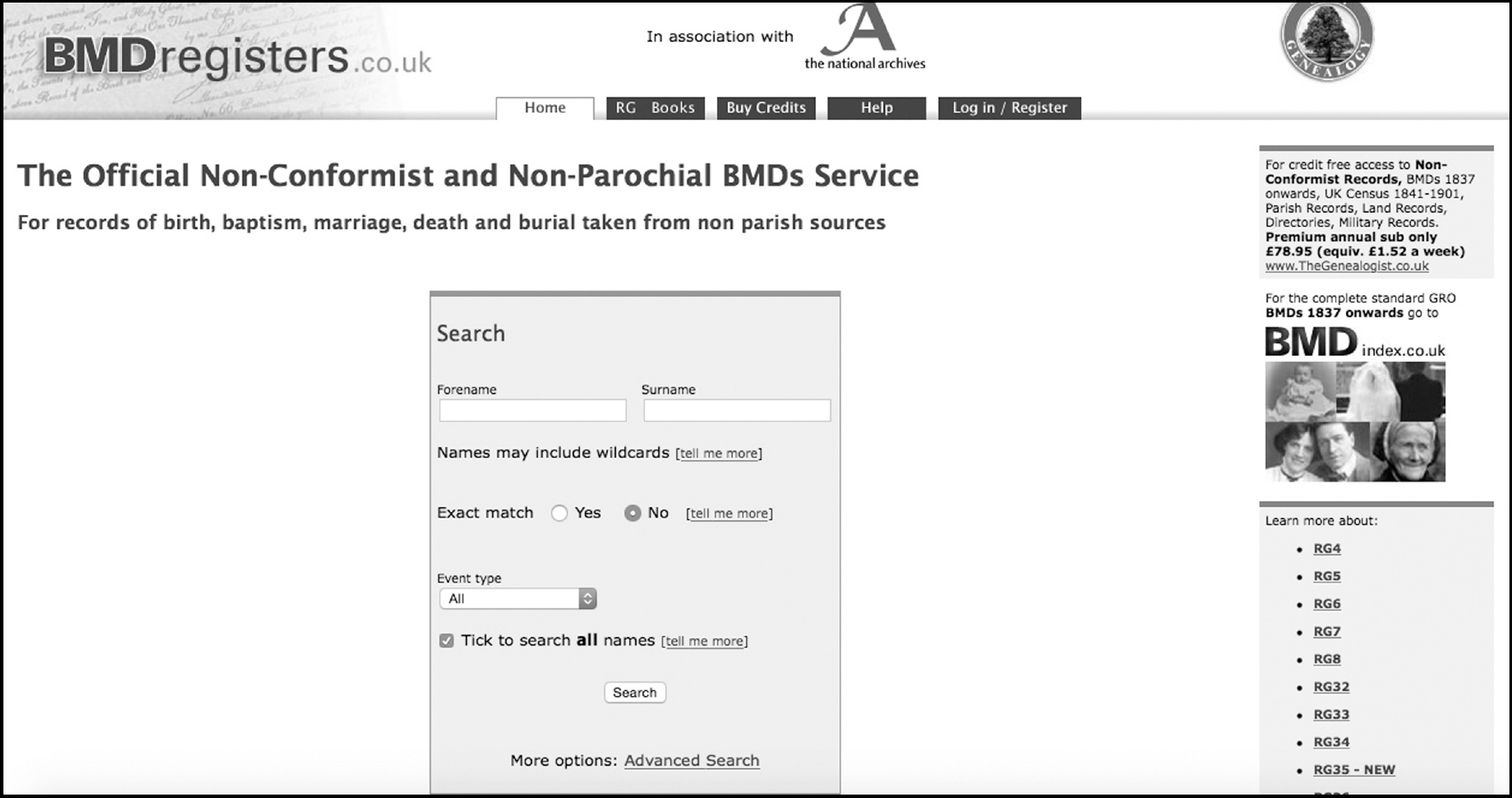

One of the most useful Nonconformist research websites is BMDregisters.co.uk, which has over 8 million BMD records from Quakers (Society of Friends), Methodists, Wesleyans, Baptists, Independents, Protestant Dissenters, Congregationalists, Presbyterians and Unitarians.

Although other commercial players have mass Nonconformist collections, the market leader in this area is TheGenealogist.co.uk. It boasts over 8 million birth/baptism, marriage and burial records drawn from TNA, including material from Quakers (Society of Friends), Methodists, Wesleyans, Baptists, Independents, Protestant Dissenters, Congregationalist, Presbyterians and Unitarians. The data is available via subscription or pay-per-view via TheGenealogist or the official BMDregisters.co.uk site. Meanwhile, Ancestry hosts the likes of the London Nonconformist registers (1694–1921) collection, drawn from its partnership with the London Metropolitan Archives.

Historians trace the earliest church labelled ‘Baptist’ back to 1609 in Amsterdam, with English Separatist John Smyth as its pastor. In short, the Baptists believe baptisms should be performed only for professing believers (rather than infants). The first congregation in the UK was established in London in 1612.

You can search the Protestant Dissenters’ Registry via BMD registers.co.uk/TheGenealogist. This served the congregations of Baptists, Independents and Presbyterians in London and within a 12-mile radius of the capital. However, parents from most parts of the British Isles and even abroad also used the registry. It was started in 1742, with retrospective entries going back to 1716, and continued until 1837.

Baptist Historical Society: baptisthistory.org.uk

Website has a useful family history page, listing some of the most important repositories of Baptist records.

Baptist History & Heritage Society: baptisthistory.org/bhhs/

In Ireland the largest Christian denomination is Roman Catholicism, followed by the Anglican Church of Ireland. Catholic parish registers for the majority of Catholic registers in Ireland were microfilmed in the 1950s and 1960s by the National Library of Ireland. Today digital images from these microfilms are now freely available on the website: registers.nli.ie. Many Church of Ireland registers of baptisms, marriages and burials were destroyed, especially in the fire at PRONI in 1922. Some of the survivors have been digitised and are available via the expanding Anglican Record Project at www.ireland.anglican.org/arp.

After the Reformation in Scotland, the greatly reduced Catholic population was concentrated in three main areas Dumfries-shire and Kirkcudbright, Moray and Aberdeenshire, Inverness-shire and the Western Isles, although Edinburgh and Glasgow also attracted many Irish catholic immigrants.

ScotlandsPeople has Catholic records from all Scottish parishes in existence by 1855 (the start of civil registration) as well as records of the Catholic cemeteries in Edinburgh and Glasgow. Baptismal registers, for example, often record dates of birth as well as baptism, and name, parents’ names (including the mother’s maiden surname), place/parish of residence, father’s occupation, witnesses (occasionally with relationship to the child) and name of the priest.

In England, following the sixteenth-century Act of Uniformity, Catholics who continued to practise their faith, could face fines, imprisonment and persecution. As a result, very few records were maintained during the seventeenth century – it only became commonplace from the mid-nineteenth century. Catholic registers often give more detail than their Anglican counterparts, and you must always remember that, as with other Nonconformists, Catholics frequently appear in Anglican sources.

BMDregisters.co.uk has the TNA material from RG 4 which include births, baptisms, deaths, burials and marriages for some Roman Catholic communities in Dorset, Hampshire, Lancashire, Lincolnshire, Northumberland, Nottinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Yorkshire. The majority cover Northumberland. Most Catholic registers, however, remain in the custody of the parish.

Catholic National Library: catholic-library.org.uk

Hosts a vast library and many transcribed mission registers (listing baptisms, confirmations, marriages and deaths).

Catholic Family History Society: www.catholic-history.org.uk/cfhs/ The Society has produced a large number of transcriptions. One randomly picked example is the ‘Registers of the Sardinian Embassy Chapel, London 1772–1841’. This contains transcriptions with indexes of twelve baptismal registers from the Sardinian Chapel in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, known as ‘the Mother Church of the Catholic faith in the Archdiocese of Westminster’. In total the indexes contain over 60,000 names.

Irish Ancestors:

irishtimes.com/ancestor/browse/records/church/catholic/

Commercial site with large database of material and useful parish map of Roman Catholic records.

Manchester & Lancashire FHS:

mlfhs.org.uk/data/catholic_search.php

Has an index to Catholic parish registers for Manchester.

Scottish Catholic Archives: scottishcatholicarchives.org.uk

Catholic Church for England & Wales: catholic-ew.org.uk

Useful for tracking down details of diocesan archives – such as Leeds Diocesan Archives (dioceseofleeds.org.uk/archives/).

The Huguenots were French Protestants who fled persecution after an edict that had allowed some religious freedoms in France was revoked. They arrived in waves during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, establishing communities in England and later Ireland. In 1718 the French Hospital was founded in London, which would become the seat of the Huguenot Society, which began to record the history of Huguenot migration and history.

Many of the refugees were artisans and craftsmen and they established a major weaving industry in and around Spitalfields. There are many French surnames associated with the Huguenots, but also some anglicised their surnames after arriving in Britain.

Again the Huguenot records on BMDregisters/ The Genealogist cover parts of London, Middlesex, Essex, Gloucestershire, Kent, Devon and Norfolk. Until 1754 Huguenots often recorded their marriages in both Huguenot and Church of England registers (although none were recorded in Huguenot registers after that date).

Huguenot Society: huguenotsociety.org.uk

The Society has transcribed and published all of the surviving Huguenot church registers. Indexed publications contain hundreds of names of members of Huguenot congregations and communities. You can search for an ancestor via the microfiche index for the first fifty-nine volumes of the Quarto Series, via individual volume indexes. There’s also huguenotsinireland.com. The Huguenot Library is currently housed at TNA in Kew. You can also read about the new Huguenot Heritage Centre in Rochester.

Huguenot Museum: huguenotmuseum.org

Jewish material is spread across a wide range of archives throughout the UK. The London Metropolitan Archives has an important collection and TNA has lots of references to Jews and Jewish communities, although these are often spread across varied record sorties – such as naturalisation records, for example. Or there’s the Scottish Jewish Archives Centre, which has synagogue registers of births, marriages and deaths, as well as copies of some circumcision registers.

The Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain is the leading light in the area and the website (www.jgsgb.org.uk) has a vast amount of useful information, plus links to important archives, online databases, research tips, news and more. You can also order copies of Marriage Authorisation Certificates for marriages before 1908.

The Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain also leads, with JewishGen, the joint Jewish Communities and Records – United Kingdom project (www.jewishgen.org/JCR-uk/). This aims to record details of all Jewish communities and congregations that have ever existed in the UK, as well as in the Republic of Ireland and Gibraltar. Currently, it boasts 7,000 pages covering over 1,000 Jewish congregations.

It has a huge number of databases, from the Bradford Jewish Cemeteries Database to the Merthyr Tydfil Jewish Community, the Caedraw School Register. There’s also the vast 1851 Anglo-Jewry Database, which covers mainly England, Wales and Scotland, but also Ireland, the Channel Islands and Isle of Man. Most of the 29,000+ entries appear in the 1851 census and represent 90+ per cent of the Jewish population in the British Isles.

JewishGen Family-Finder: www.jewishgen.org/jgff/

Gives surnames and ancestral towns of more than 500,000 entries, by adding your family details it will increase the chances of linking with other researchers looking for the same surname. There’s also the JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry, boasting entries from 4,200 cemeteries and burial records in 83 countries.

Scottish Jewish Archives Centre: sjac.org.uk

Founded in 1987 and based in Scotland’s oldest Synagogue – the Garnethill Synagogue in Glasgow. Has synagogue minute books and registers, membership lists, personal papers and photographs. The Archive maintains a collection of Jewish newspapers, which often contain personal announcements.

British-Jewry: www.british-jewry.org.uk

Hosts several databases from the Portsmouth circumcision database to the vast Leeds Database.

Judaica Europeana: www.judaica-europeana.eu

Yad Vashem:

www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/remembrance/names/index.asp

Working to recover the names of the 6 million Jews who perished in the Holocaust, and adding them to the Central Database of Holocaust victims.

Jewish Historical Society of England: jhse.org

USC Shoah Foundation: http://sfi.usc.edu

Beth Shalom Holocaust Web Centre: www.ajex.org.uk

Jewish Museum London: jewishmuseum.org.uk

Manchester Jewish Museum: manchesterjewishmuseum.com

Methodism, or the Methodist movement, which actually covers more than one denomination, was born out of the life and teachings of John Wesley (1703–91). Both John and his brother, the hymn writer Charles Wesley, were ordained Anglican clergy. Methodism was organised by chapels at the centre of large ‘circuits’ around which particular ministers would preach, perform baptisms and even marriages (before 1753). The North Lancashire District, for example, currently comprises eighteen circuits of town and country churches.

Methodism also spread to Ireland – the first Methodist society was formed in Dublin in 1746, and John Wesley first visited Ireland the following year. By the time of his death in 1791 Irish Methodist membership numbered over 14,000.

Via BMDregisters you can search Wesleyan Methodist Records from the Wesleyan Methodist Registry, set up in 1818 and continued until 1838. It provided registration of births and baptisms of Wesleyan Methodists throughout England and Wales and elsewhere.

Methodist Historical Society of Ireland:

Maintains an extensive archive relating to Methodism in Ireland, including records of individual churches and journals/periodicals. The website has a useful index of Irish Methodist churches, chapels and preaching houses, as well as guides to records such as Irish Methodist baptismal and marriage records.

My Methodist History: mymethodisthistory.org.uk

Community archive network that encourages users to share photos and stories. There are also sites My Primitive Methodist Ancestors (myprimitivemethodists.org.uk) and My Wesleyan Methodist Ancestors (mywesleyanmethodists.org.uk).

Methodist Central Hall: church.methodist-central-hall.org.uk

Contains the names of over 1 million people who donated a guinea to the Wesleyan Methodist Twentieth Century Fund between 1899 and 1904.

Methodist Archives and Research Centre:

ibrary.manchester.ac.uk/searchresources/guidetospecialcollections/methodist/

Manchester University’s Methodist Archives and Research Centre houses an enormous collection of material relating to the early days of the denomination, and key figures in its foundation and consolidation. It also holds Methodist newspapers and periodicals which can be useful for tracking down ministers’ obituaries. Wesley Historical Society: wesleyhistoricalsociety.org.uk

You can search the Protestant Dissenters’ Registry via BMD registers.co,uk/TheGenealogist. This served the congregations of Baptists, Independents and Presbyterians in London and within a 12-mile radius of the capital. However, parents from most parts of the British Isles and even abroad also used the registry. It was started in 1742, with retrospective entries going back to 1716, and continued until 1837.

Presbyterian Historical Society of Ireland:

presbyterianhistoryireland.com

Presbyterian Historical Society: www.history.pcusa.org

Quaker history begins with George Fox who established the Religious Society of Friends in the mid-seventeenth century. Members of the society became known as ‘Quakers’ because some of them trembled during religious experiences. Many Quakers faced persecution and many emigrated to North America.

There were four hierarchical levels of Quaker meetings and registers were originally kept by local or monthly meetings. From 1776 copies were also sent to the quarterly meeting (and these are now held at TNA). The registers were also recorded in ‘digests’, which contain much of the detail of the originals, and are often housed at local record offices and at Friends House – the Quaker headquarters in London. Important online sources available through TheGenealogist are the Quaker BMD registers held by TNA (series RG 6). They include registers, notes and certificates of births, marriages and burials from the years 1578 and 1841.

Quakers kept meticulous registers of births (Quakers did not practise baptism), marriages and deaths, as well as other records related to congregations. Register books began to be kept by Quaker meetings from the late 1650s, but in 1776 their whole registration system was overhauled. So post-1776 birth entries, for example, contain the date of birth, place of birth (locality, parish and county), parents’ names (often with the father’s occupation), the child’s name and names of the witnesses.

Quakers’ refusal to pay tithes led to them being subject to fines and even imprisonment. They were anxious to record these persecutions so books of sufferings were kept by monthly or quarterly meetings, and then recorded in the ‘great book of sufferings’ in London.

Library of the Religious Society of Friends: quaker.org.uk

Has details of the official Library of the Religious Society of Friends.

Quaker FHS: qfhs.co.uk

The Society website is very useful for getting to grips with unique Quaker records. Explains types of records such as minute books, membership lists and digests.

Quaker Archives, Leeds University Library:

library.leeds.ac.uk/special-collections

Comprise the Carlton Hill collection (broadly covering Leeds, Bradford, Settle and Knaresborough) and the Clifford Street collection (York and Thirsk areas, as well as Yorkshire-wide material).

Yorkshire Quaker Heritage Project:

www.hull.ac.uk/oldlib/archives/quaker/

● As the refusal to bear arms is central to Quaker beliefs, you may be able to find references to Quakers in the records of Conscientious Objectors, held by TNA.

● Quakers, the Society of Friends, used the Julian Calendar up until March 1752, after which the vast majority of their records adopted the Gregorian Calendar. According to the Julian Calendar, the first day of the new year was 25 March ‘Lady Day’, so a full year would run from 25 March to 24 March.

● Roman Catholic registers were generally not kept before 1778 and many of them are written in Latin. Catholic baptism registers will usually show the names of godparents.

● The Historic Chapels Trust site (www.hct.org.uk) hosts images and information about redundant chapels and places of worship.

Barratt, Nick. Who Do You Think You Are? Encyclopedia of Genealogy, Harper, 2008

Herber, Mark. Ancestral Trails: The Complete Guide to British Genealogy and Family History, The History Press, new edn 2005

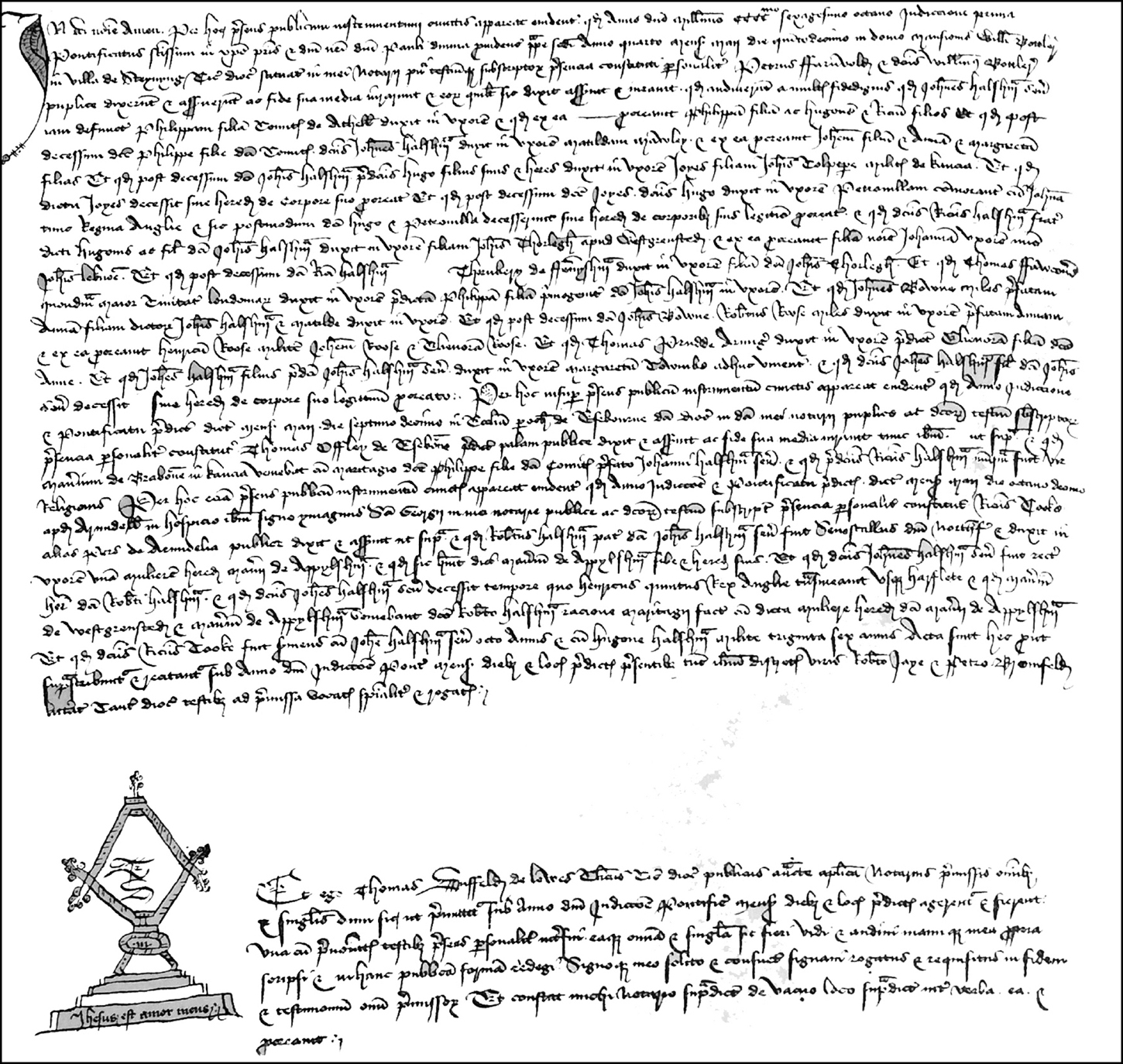

Wills can reveal troubled relationships. Cardiff gent Miles Bassett put his pen to paper in the seventeenth century, leaving behind a document that is still preserved within the National Library of Wales’ probate collection.

And [I could put] as little confidence in my crabbed churlish unnatural, heathenish, and unhuman sonne inlawe Leyson Evans and Anne his wife; I never found noe love, shame nor honestie with them. . . . but basenesse and falsehood, knaverie and deceipt in them all, ever unto me . . . they were my greatest Enemies, I had no comfort in anie of them, but trouble & sorrow ever, they sued me in Londone in the Exchequier and in the Comonplease, and in the Marches at Ludlowe, and in the greate Sessions at Cardiff and thus they have vexed me ever of a long time.

The 1627 will and inventory of carpenter Nicholas Perry of ‘New Sarum’ (Salisbury) describes how at a time of plague Perry took refuge in nearby Combe Bissett, and took the opportunity to make a nuncupative will (one dictated rather than written down). He made the will because his son Nicholas had threatened to ‘use his wife hardly’ and throw her out. So, Perry decided to give all his property to his younger son, Anthony. The associated inventory, not surprisingly, includes a lot of ‘timber stuff’.

All this should hopefully encourage you to look into probate sources. Wills can not only offer you insights into a person’s wealth and possessions, but also give a census-like snapshot of a household, with all kinds of relationships revealed, and, if there’s an associate inventory, sometimes give you a virtual room by room tour of the house and belongings. In short, they can contain revealing information that is not available from any other source, and they stretch back to long before the census or civil registration. But they can also be hard to read, fragmentary, full of archaic and technical legalese, and, especially if there is no index or other finding aid, hard to track down.

Where there’s wealth there’s often a will, but not always, and lots of people of more modest means also left wills. Many left unproven wills to avoid legal fees, and even if your ancestor did not leave a will, they may have appeared in someone else’s. According to the useful FamilySearch wiki on the subject of English probate material, it is estimated that ‘courts probated estates (with or without a will) for fewer than 10 percent of English heads of households before 1858. However, as much as one-fourth of the population either left a will or was mentioned in one.’ In Scotland, according to the National Records of Scotland guide to Wills and Testaments, even as late as 1961, only ‘forty three per cent of Scots dying in that year left testamentary evidence of any sort’.

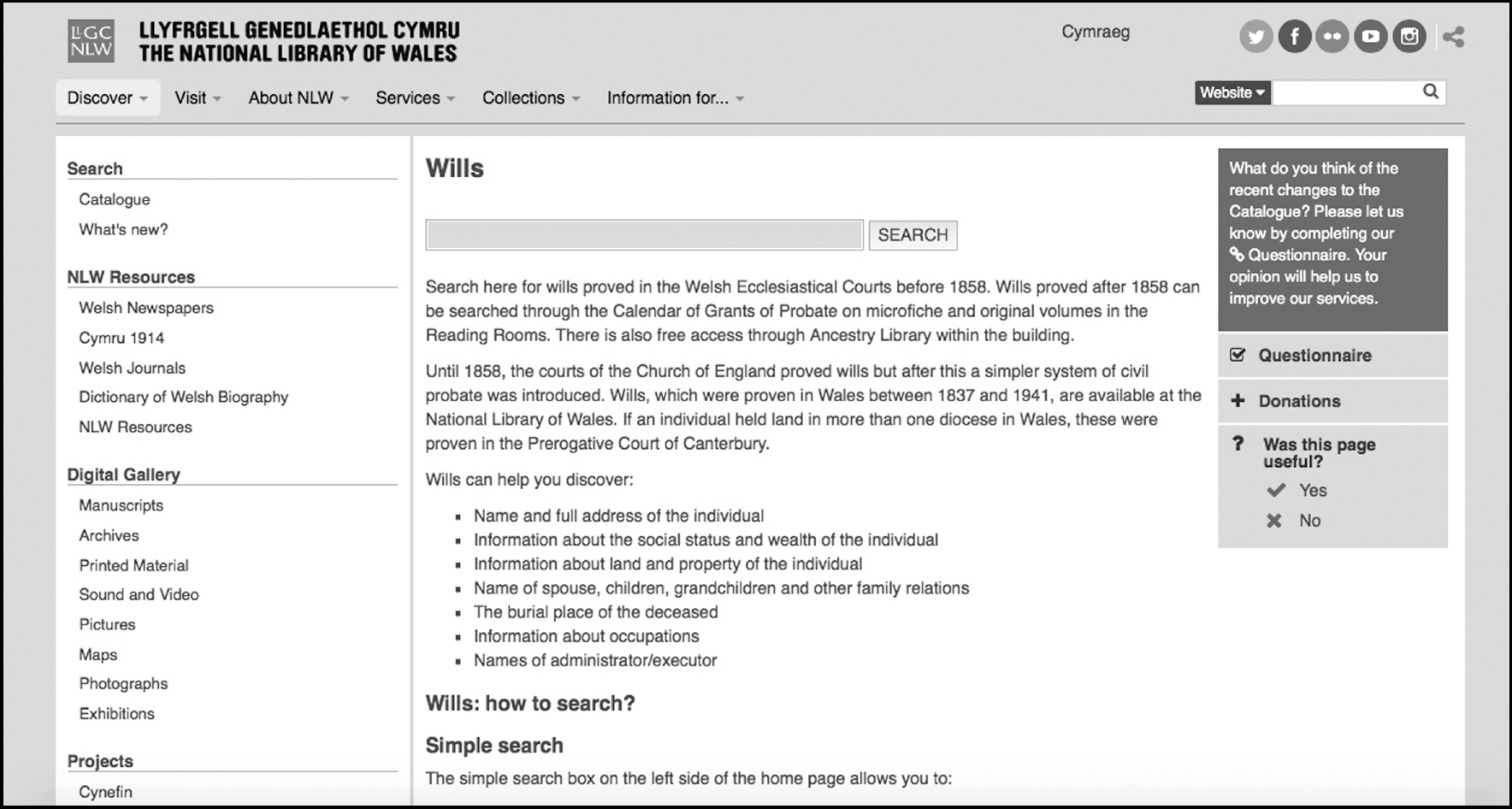

You should investigate what is online, as region to region, collection to collection this varies a great deal. Some archives have detailed research guides, indexes and even digitised material. Should you wish to know more about the aforementioned Miles Bassett, for example, you can explore the document via the National Library of Wales’ wonderful database of free digital images of pre-1858 wills proved in Welsh ecclesiastical courts at www.llgc.org.uk/probate. And you can also view the allied inventory (ref: LL 1680-10) to see what they were all squabbling over.

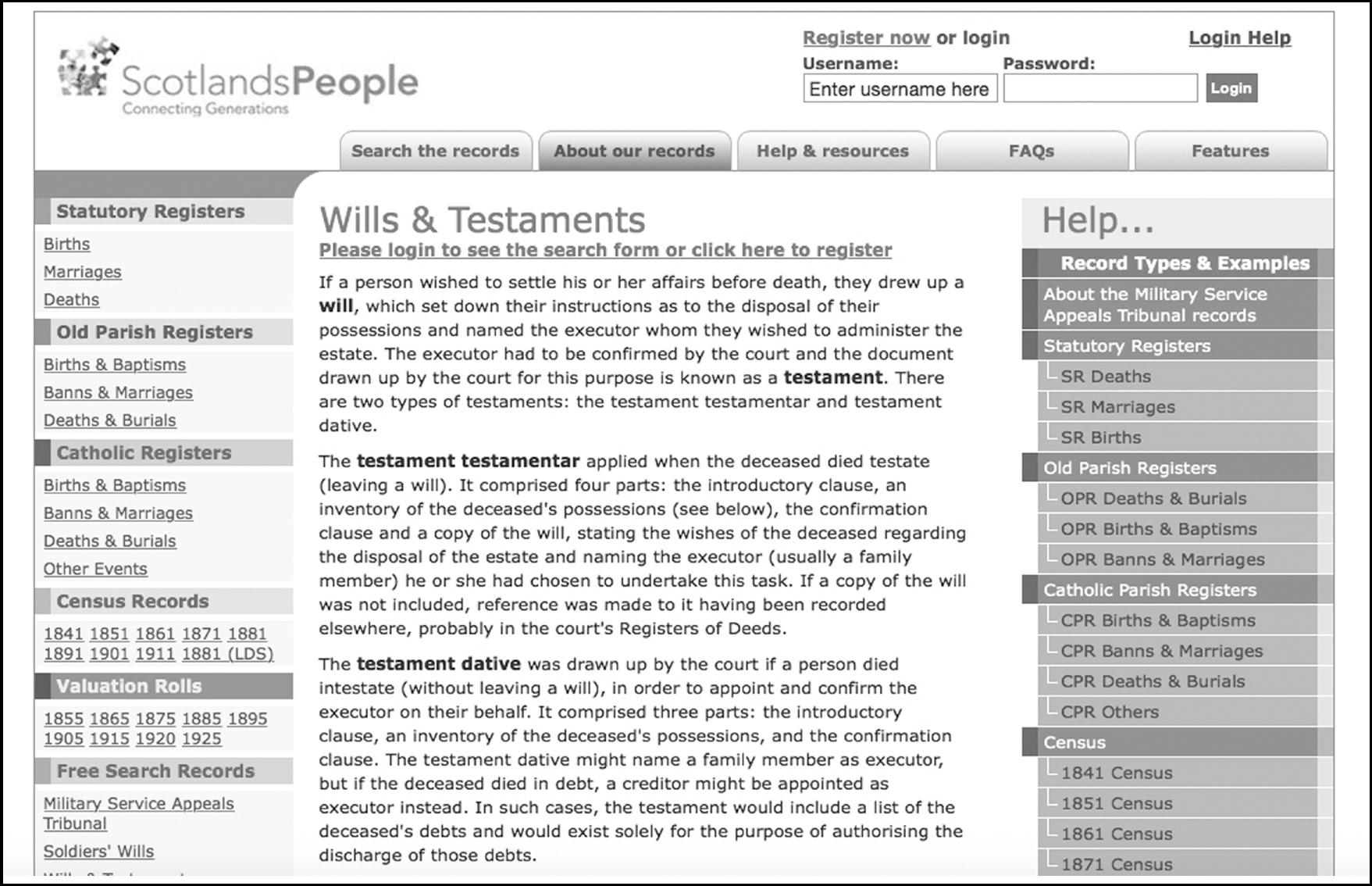

Scottish testaments from between 1514 and 1925 have been digitised and copies are available through ScotlandsPeople.

In Scotland ‘testament’ is the collective term for documents relating to wills and inventories. After a person died, if there was a will it would be taken to the sheriff courts to be confirmed, producing a document called a ‘testament testamentar’ (a grant of probate). If there was no will a ‘testament dative’ would be drawn up (a letter of administration) which would give power to executors to deal with the estate.

Testaments from between 1514 and 1925 have been digitised and copies are available through ScotlandsPeople, which also contains an index with over 611,000 index entries, each listing surname, forename, title, occupation and place of residence (where known) of the deceased person, the court in which the testament was recorded and the date. Index entries do not include names of executors, trustees, heirs to the estate, date of death or value of the estate.

Before 1823 testaments were recorded in the Commissary Court with jurisdiction over the parish in which the person died. And just as England’s diocesan boundaries won’t match ancient county boundaries, so these court boundaries, which roughly corresponded to medieval dioceses that existed before the Reformation in Scotland, bear no relation to county boundaries. Also, remember that the Edinburgh Commissary Court confirmed testaments for those who owned property in more than one area, and for Scots who died outside Scotland. And from 1824 Sheriff Courts took over responsibility for confirmation of testaments.

There are other sources online. Ancestry, for example, recently issued its National Probate Index – Calendar of Confirmations and Inventories between 1876 and 1936. The National Records of Scotland and ScotlandsPeople websites also have clear and concise guides to wills and testaments in Scotland (the latter going into more detail). In addition, you can view examples of will and associated documents from different areas.

There are lots of technicalities and idiosyncrasies to watch out for, but broadly speaking, prior to 1858, the situation in England and Wales was similar to pre-1824 Scotland in that the Church of England courts handled probate.

There were more than 300 Church probate courts set within a hierarchy – the higher court would handle the probate if the testator owned property in two or more areas. The lowest were the peculiar courts, which had jurisdiction over small areas. Next came archdeaconry courts (divisions within dioceses), bishops’ courts (the highest diocesan courts), prerogative courts and the Prerogative Court of Canterbury – the highest court of all, used for wills of testators who died or owned property outside of England, foreigners who owned property in England, military personnel, persons having property in more than one probate jurisdiction and wealthier individuals.

The National Library of Wales hosts a database of free digital images of pre-1858 wills proved in Welsh ecclesiastical courts at www.llgc.org.uk/probate.

So, to track down probate records you need to try to confirm the parish and year in which your ancestor died, then confirm which court (or courts) had jurisdiction. Then you can look for any surviving indexes and records.

The Nicholas Perry will quoted above, for example, comes from the diocese of Salisbury probate collection preserved at the Wiltshire & Swindon History Centre. However, this diocese is much bigger than the county of Wiltshire, meaning the collection also includes wills from Berkshire, Dorset and Devon, as well as Wiltshire. Indeed, the collection includes the 1680 will of Edward Wallis of ‘Stoke next Guildford’ in Surrey, describing him as being of an ‘infirme and crazie body’.

From January 1858 the Principal Probate Registry, a network of civil courts called probate registries, replaced the ecclesiastical probate courts. And you can search the official government index to wills and administrations in England and Wales via the Probate Search website (probatesearch.service.gov.uk/#wills). This includes wills/administrations between 1858 and 1995 (and 1996 to present), as well as an index to soldiers’ wills (1850–1986), and there’s the National Probate Calendar (1858–1966) available via Ancestry.

This facsimile of a 1468 deed was printed in 1876 insomnia cure Memorials of the Family of Scott, of Scot’s Hall in the County of Kent, by James Renat Scott.

Before a will can take effect a grant of probate must be made by a court. And if someone dies without a will, the court can grant letters of administration for the disposal of the estate. Since 1858 grants of probate and administration in Ireland have been made in the Principal and District Registries of the Probate Court (before 1877) or the High Court (after 1877). These are indexed in the calendars of wills and administrations that are held at the National Archives of Ireland. Up to 1917, the calendars cover the whole of Ireland. After 1918 they cover the twenty-six counties in the Republic while indexes covering the six counties of Northern Ireland are at PRONI. The National Archives of Ireland testamentary calendars can be searched online (1858–1920 and 1922–82).

Before 1858 grants of probate and administration were made by the courts of the Church of Ireland (the Prerogative Court and the Diocesan or Consistorial Courts). There are separate indexes of wills and administrations for each court and some indexes have been published – such as the Vicar’s Index to Prerogative Wills, 1536–1810 and the Indexes to Dublin Grant Books and Wills, 1270–1800. Again, you can find more detail via the National Archives of Ireland research guides (nationalarchives.ie).

● There’s a natural assumption that only the more well-to-do left wills, but this is not always the case, and there’s also a chance you may find references to your ancestor in other people’s wills.

● The eldest son in family wills may not actually be mentioned, because he automatically inherited property of the deceased father.

● Technically, a will conveys immovable property to heirs and a testament conveys personal moveable property. But in general the term ‘will’ usually refers to both.

● A ‘codicil’ is a signed addition to a will.

● If someone dies ‘intestate’ (without leaving a will), then you may find ‘Letters of Administration’. This a document that appoints someone to preside over the distribution of the estate. There may also be a letter of administration attached to a will, if the named executor is deceased, unwilling or unable to act.

● Other potential probate sources you may come across include ‘act books’ (accounts of court actions) and ‘bonds’ (written guarantees that a person will perform tasks set by the probate court).

● Very few wills and probate documents survive before around 1400.

● Before 1882 a wife who died before her husband could not make a will except with her husband’s consent or under a marriage settlement created before her marriage.

● Until 1858 the courts of the Church of England proved wills but after this a simpler system of civil probate was introduced.

● On 12 January 1858, the Court of Probate was established in London to prove all wills throughout England and Wales. Until 1870 most women did not make a will as they were not allowed officially to own any property. After 1870 a married woman could make a will and bequeath property settled upon her for her separate use, but only under certain specific circumstances.

● The Civil War disrupted the probate process as Parliament abolished ecclesiastical courts in 1653 (restored in 1661). Wills proved during this period are filed at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury.

● Before 1750 heirs often did not prove wills in order to avoid court costs. Some archives maintain collections of unproved wills.

● Starting in 1796, a tax or death duty was payable on many estates with a certain value. Read more about death or estate duty wills at nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/death-duties-1796-1903-further-research/.

● Until 1833 real property could be ‘entailed’. This specified how property would be inherited in the future. An entail prevented subsequent inheritors from bequeathing the property to anyone except the heirs specified in the original entail.

Find a will: probatesearch.service.gov.uk/#wills

The official government probate search engine. Use this to find wills from January 1858 onwards proved in the Principal Probate Registry, a network of civil courts that replaced the ecclesiastical courts in England and Wales. A name and year of death is required to find wills, which should be ready for download within ten days of order – costing £10. Please note this was Beta testing at the time of writing so the above address may change.

FamilySearch wiki: familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Main_Page

FamilySearch wiki pages concentrating on individual counties often have links to probate records, detailing what survives where.

In addition, you’ll sometimes find links to probate collections that have been digitised and made available here – such as the Cheshire Probate Records, 1492–1940 collection at familysearch.org/search/collection/1589492.

The National Archives: nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/wills-1384-1858/

You can search Discovery for records of Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) wills in series PROB 11 (1384–1858). These are all registered copy wills – copies of the original probates written into volumes by clerks at the Church courts. Other TNA guides/collections include wills of Royal Navy and Royal Marines personnel (1786–1882) and county court death duty registers and famous wills (1552–1854).

National Archives of Ireland: nationalarchives.ie

Find out more about the National Archives of Ireland’s probate collections. You can search Calendars of Wills and Administrations (1858–1922) and there’s an online database of soldiers’ wills (soldierswills.nationalarchives.ie), as well as a useful research guide with a glossary of legal terms.

ScotlandsPeople: scotlandspeople.gov.uk

Trawl the index to Scottish wills and testaments dating from 1513 to 1901 (listing surname, forename, title, occupation and place of residence), as well as the associated database of soldiers’ wills.

National Library of Wales: llgc.org.uk

Explore 193,000 records of wills proved in the Welsh ecclesiastical courts prior to the introduction of civil probate in 1858. You can either search the entire index, or narrow down by individual courts.

Public Record Office of Northern Ireland:

www.proni.gov.uk/index/search_the_archives.htm

Details of all PRONI’s online probate collections, including Will Calendars – a free index of wills from the district probate registries of Armagh, Belfast and Londonderry (1858–1943).

North East Inheritance Database:

familyrecords.dur.ac.uk/nei/data/

A database of pre-1858 probate records (wills and related documents) covering Northumberland and County Durham. Digital images of the original probate records (including wills and inventories, 1650–1857; copies of wills, 1527–1858; executors’ and administration bonds, 1702–1858) are also available through FamilySearch.

The Gazette: www.thegazette.co.uk/wills-and-probate

Includes wills and probate notices printed in the London, Edinburgh and Belfast gazettes.

Ancestry: search.ancestry.co.uk/search/db.aspx?dbid=1904

Ancestry’s probate collections include important National Probate Calendars.

TheGenealogist: thegenealogist.co.uk

Diamond subscribers can enjoy several useful probate collections including many county wills indexes covering Yorkshire, Staffordshire, London, Leicestershire and more, as well as the PCC indexes and indexes to some Irish and Scottish wills.

England & Wales Published Wills & Probate Indexes, 1300–1858.

Essex Wills: seax.essexcc.gov.uk

Search and access images of Essex probate material held at Essex Record Office.

Wiltshire Wills: www.wshc.eu/our-services/archives.html

Gibson, Jeremy and Else Churchill. Probate Jurisdictions: Where to Look for Wills, Federation of Family History Societies, 2002 (for probate indexes produced since Gibson and Churchill’s guide go towww.dur.ac.uk/a.r.millard/genealogy/probate.php)

Grannum, Karen and Nigel Taylor. Wills and Probate Records: A Guide for Family Historians, The National Archives, 2009

In 1913 Joanna Archer had a child out of wedlock. The father was Ishmael Cummings, a Sierra Leonean doctor and one of several African professionals working at Newcastle’s Royal Victoria Infirmary, where Joanna was junior matron. Their son, Ivor Cummings, would grow up in Addiscombe, south London, where he suffered prejudice because of the colour of his skin – on one occasion fellow pupils at Whitgift School setting light to his curly hair.

Ivor wished to become a doctor, but social barriers of the time were such that he abandoned those dreams, instead forging a career as a civil servant, becoming a well-known figure in London’s black community. He was working as a civil servant in the Colonial Office when early one morning in June 1948 he was sent to Tilbury Docks. He was there to meet an initial shipload of Jamaicans who were arriving in Britain for the first time aboard the Empire Windrush.

The arrival of the Windrush is a watershed moment in the history of migration to Britain. It wasn’t some obscure event that has since been given greater significance by historians. The day before the ship arrived the London Evening Standard sent out an aeroplane from Croydon Aerodrome to photograph the vessel as she approached. The image and news of the approaching migrants made the front page under the headline: ‘Welcome Home! Evening Standard ’plane greets 400 sons of Empire’.

‘From the air,’ wrote Standard reporter Denise Richards, ‘the Empire Windrush was little different from many of the ships which sail daily, but to four hundred people on board she was the beginning of a new life. . . . The airplane circled for fifteen minutes, and gradually apprehension turned to joy as the passengers realised they were receiving their first welcome to England.’

The Windrush had set off from Kingston, Jamaica on Empire Day, 1948. The majority of the migrants paid £28 to travel to Great Britain, responding to job advertisements that had appeared in local newspapers. Britain was suffering from major post-war labour shortages, and the passenger lists from that first arrival record an array of occupations – welder, carpenter, mechanic, painter, tailor, bookkeeper, farmer and fitter. To begin with many settlers were housed in a deep air raid shelter in Clapham Common, many eventually settling in nearby Brixton as this was the location of the nearest labour exchange.

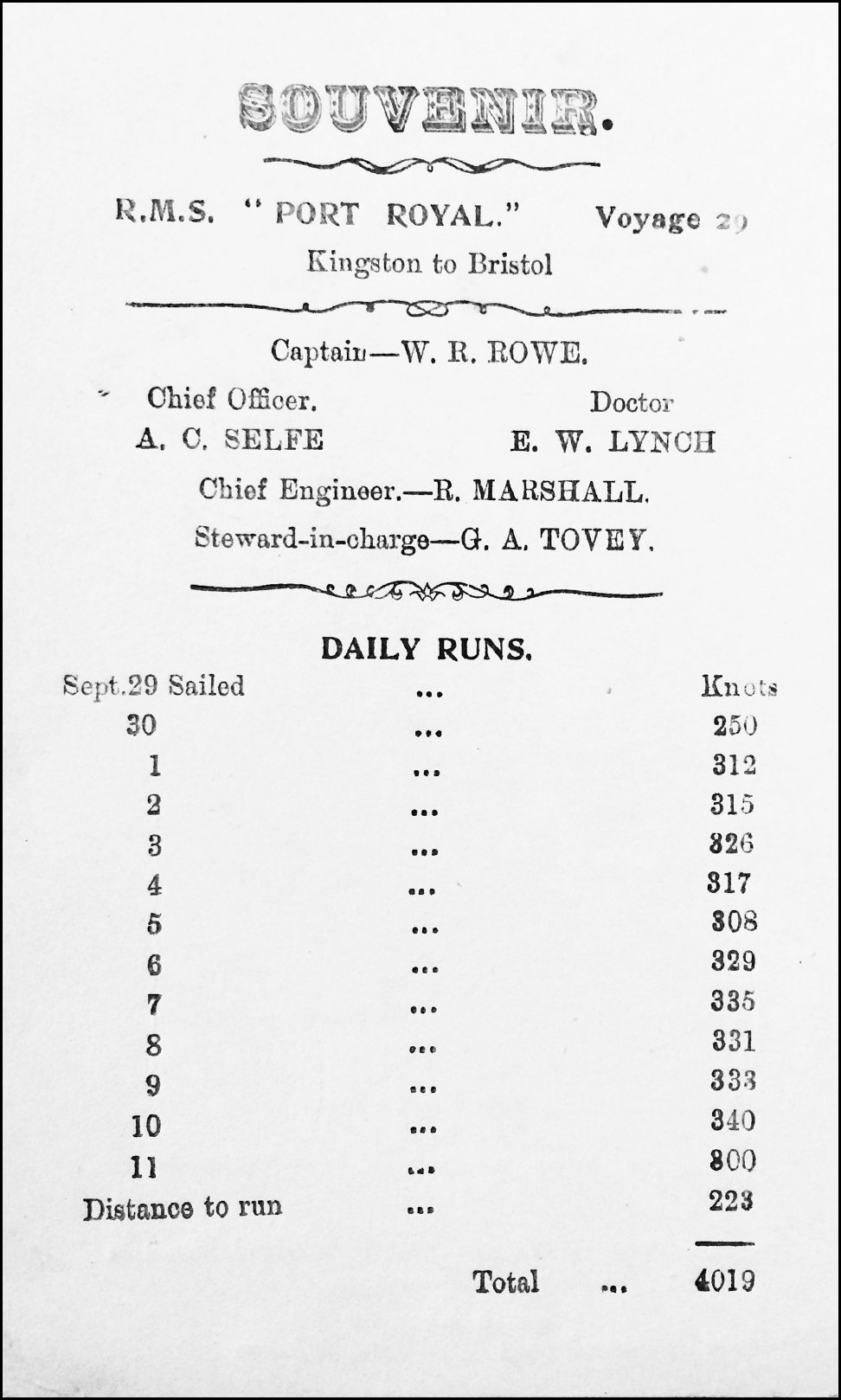

Souvenir postcards of a sea voyage. This one records RMS Port Royal’s run from Kingston to Bristol, captained by W.R. Rowe.

The arrival of the Windrush is just one chapter in the story of migration in and out of the British Isles and Ireland. Other chapters include the Huguenots, members of the French Protestant Church who left their homes in France to escape religious persecution; there was the forced displacement of the Highland Clearances; and the mass starvation, disease and emigration of the Great Hunger in Ireland.

Trade pulled individuals and families across country borders, from the nineteenth-century Irish navvies who helped build Britain’s railways to employees of the Hudson Bay Company. The East India Company played a vital role in British expansion and control overseas, for hundreds of years employing thousands of traders, administrators, politicians, sailors and soldiers. There were also the ‘assisted’ migrations, such as the Home Children of the later Victorian period, or the Highlands & Islands Emigration Society, which assisted almost 5,000 individuals to leave western Scotland for Australia between 1852 and 1857. And there were forced migrations, the thousands of criminals transported firstly to North America and later to Australia.

Migration sources are complex. To keep things simple, I will first look at records of migrants entering the British Isles, before turning to records of those moving elsewhere.

TNA’s guide to immigration research begins by warning the reader that tracing immigrants can be difficult because many records held there are incomplete, in addition to the fact that some record series only cover certain periods or types of immigrant.

In general, surviving records refer to aliens (a non-citizen of the parent country), ‘denizens’ (a permanent resident, but not a citizen) and the process of naturalisation – when someone from outside the country becomes a legal citizen.

The earliest TNA sources that may potentially include references to foreign subjects and aliens include Chancery records, records of the Exchequer and state papers. Some early lists of people mentioned in the Calendar of State Papers, Domestic (1537–1625) can be searched via British History Online (british-history.ac.uk). Another source is Parliament or patent rolls which contain records of acts of naturalisation and grants of denizations. There are also Treasury in-letters, which contain references to refugees and other foreign people who received annuities, pensions and other payments in return for services rendered to the Crown. (There are indexes to the Calendar of Treasury Papers between 1556 and 1745.)

A great online resource for people researching in this early period is the England’s Immigrants Database at englands immigrants.com. This is a fully searchable database containing over 64,000 names of people known to have migrated to England between 1330 and 1550 – covering the Hundred Years War, the Black Death, the Wars of the Roses and the Reformation.

The situation simplifies after 1793. Mass migration during this period (caused largely by the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars) led to the passing of the Aliens Act of 1793. From then all arriving migrants had to register with the Justice of Peace, providing personal information, which would then be passed to the Aliens Office. The original Aliens Office certificates have not survived (although some indexes have), but original Justice of Peace records relating to arrivals may survive locally at county record offices – normally among quarter sessions material. Hull History Centre, for example, has certificates of arrival of aliens issued at the port between 1793 and 1815.

A second Aliens Act was passed in 1836. Now newly arrived migrants had to sign a certificate of arrival, and these certificates, for arrivals to England and Scotland, are held at TNA in series HO 2. The certificates should record nationality, profession, date of arrival, last country visited and other details. Through Ancestry, thanks to its partnership with TNA, you can search Alien Arrivals (1810–11 and 1826–69) and Aliens’ registration cards (1918–57) covering the London area only.

Another useful and accessible source is not part of migration records as such, but registers kept by settled communities. The non-parochial registers contained within RG 4 and RG 8 at TNA date from the sixteenth to twentieth centuries and are records kept by the French, Dutch, German and Swiss churches in London and elsewhere. These can be searched via BMDregisters.co.uk.

Other important TNA collections include: naturalisation case papers (1789–1934), which can be searched via Discovery; incoming passenger lists (1878–1960, held in BT 26), documenting people arriving from countries outside Europe and the Mediterranean area, available via Ancestry. The latter include details such as name, date of birth and age, ports of departure and arrival, and details of the vessel. Although remember that many of the pre-1890 lists were irregularly destroyed by the Board of Trade. Also available via Ancestry are the naturalisation certificates and declarations of British nationality (1870–1912). These will usually list the immigrant’s name, residence, birthplace, age, parents’ names, name of spouse (if married), occupation and children (if still of dependent age).

The National Archives’ immigration guide leads to all kinds of useful online resources.

Thanks partly to post-war labour shortages between the years 1948 and 1962 there were no restrictions on immigrants from Commonwealth countries, and the British Nationality Act of 1948 made it relatively simple for migrants to obtain citizenship. Certificates of citizenship issued by the Home Office from this period have also survived and can be found at TNA in HO 334.

Before you start your research into a migrant leaving the UK and Ireland, it’s useful to have the name of the ship they travelled on, and the ports of departure and arrival. This is easier said than done and while there are some online resources that can help you find this information, coverage is patchy.

Findmypast, through partnership with TNA, boasts outward passenger lists between 1890 and 1960. These were lists from both UK and Irish ports, recording those travelling to the USA, Canada, India, New Zealand and Australia.

Other important collections include Foreign Office records, such as passport registers and indexes, or, for researching individuals who migrated (or were transported) to Australia, there are the New South Wales original correspondence, entry books and registers (between 1784 and 1900). These contain lists of names of emigrants, settlers and convicts. The website of The National Archives of Australia has more information about emigration to Australia. In addition, details of some 8.9 million free settlers to New South Wales, 1826–1922 can be searched and downloaded online at ancestry.com.au, for a fee. Other Antipodean sources include registers of cabin passengers emigrating to New Zealand (1839–50).

TNA has original correspondence and entry books (1814–71), which can be explored via Discovery, and Land and Emigration Commission papers (1840–94), which include registers of births and deaths of emigrants at sea from 1854 to 1869, lists of ships chartered from 1847 to 1875 and registers of surgeons appointed from 1854 to 1894. You can also search Discovery by name for case histories of all those evacuated by the Children’s Overseas Reception Board during the Second World War.

Another common area of research is child migration. According to TNA, it is estimated that between 1618 and 1967 about 150,000 children were sent to the British colonies and dominions as part of various schemes, mainly to America, Canada and Australia, but also Zimbabwe (Rhodesia), New Zealand, South Africa and the Caribbean. ‘Many of the children were in the care of the voluntary organisations who arranged for their migration. Child emigration peaked from the 1870s until 1914 – about 80,000 children were sent to Canada alone during this period.’ (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/emigration/).

The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1850 allowed Boards of Guardians to send children under 16 overseas. But any records of specific cases are most likely to survive within records held in local archives. Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives’ Poor Law material includes the General Registers of the Poor for Peterhead. One entry concerns 4-year-old Elspet Niddrie, whose dying mother and adult half-sister were unable to care for her. The council decided she should be sent to her aunt, Jane Lemmon (née Niddrie) who had emigrated to America in 1904. The case ends with the Inspector of the Poor writing: ‘Passage paid to Boston USA and sent to Aunt . . . sailed today on Allan Liner Numidian’. (Elspet lived in Massachusetts, went on to marry a bus driver, had four children and died in December 1983.)

There are TNA-held Colonial Office reports on pauper child emigrants resident in Canada (1887–92). These comment on condition, health, character, schooling and church attendance of each child, as well as the children’s own view of their new homes. They also record the union or parish from which they were sent, as well as each child’s name, age and host’s name and address. Remember too that useful information may reside in records of initiatives held by the likes of Dr Barnardo’s Homes, the Overseas Migration Board and the Big Brother emigration scheme.

Away from economic and assisted migrants, there were thousands of forced migrants – namely criminals transported first to North America and later to Australia. This began in 1615, when criminals were first shipped to America or the West Indies, often sent to work on plantations. It is estimated that more than 50,000 English men, women and children were sentenced, crimes ranging from the theft of a handkerchief to highway robbery. One important source for this period is Peter Coldham’s landmark work The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage (and via Ancestry you can also access More Emigrants in Bondage, 1614–1775).

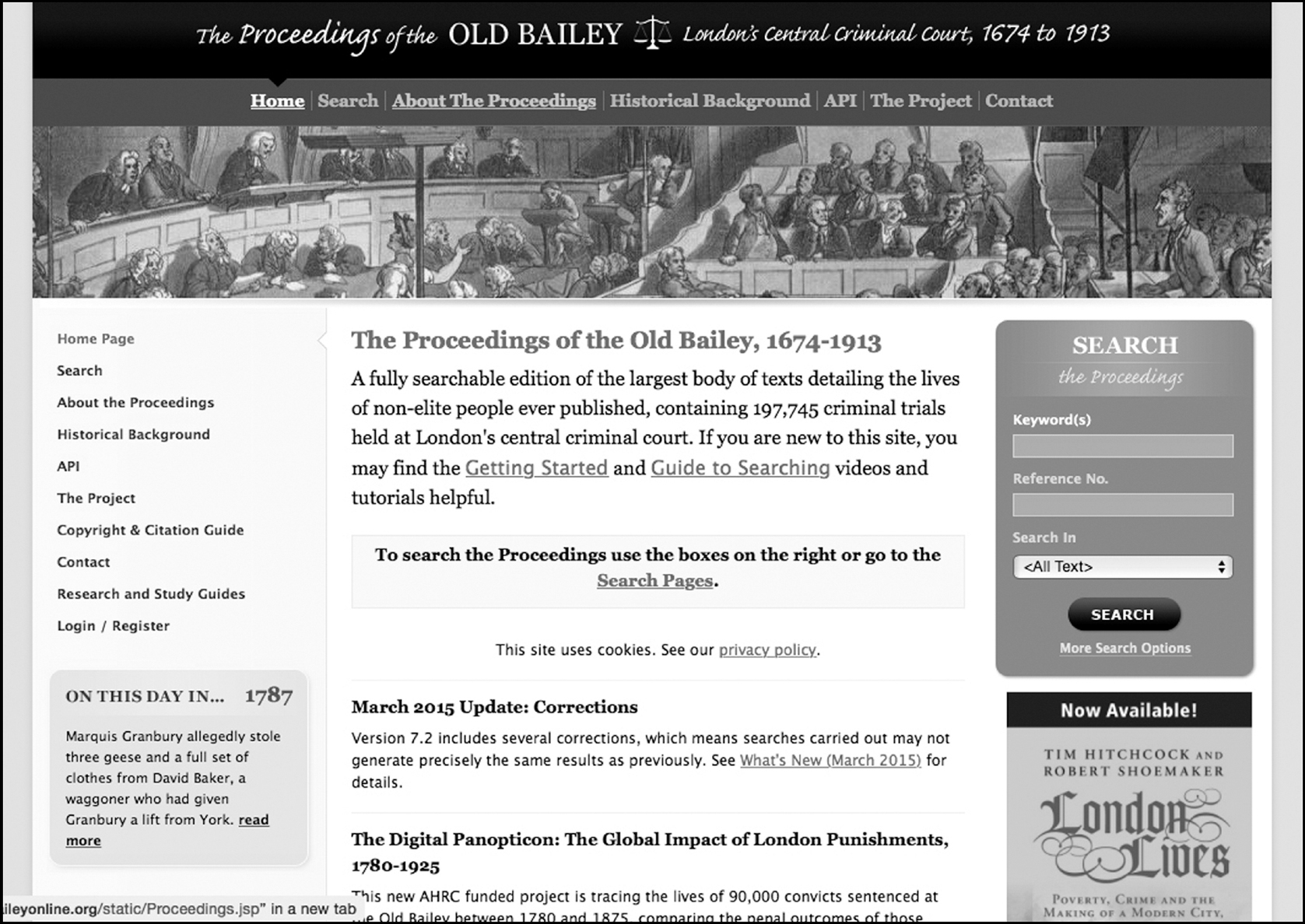

After the American Revolution in 1776 convicts had to be sent elsewhere and the first convict ships, known as the First Fleet, arrived in Australia in January 1788. The flow of convicted transportees finally slowed during the 1850s and ceased altogether when the system was abolished in 1868. While the records for this period of transportation are fractured, there are lots of websites with data and information about the history of transportation and how to research individuals. Amateur site Convicts to Australia (members.iinet.net.au/~perthdps/convicts/) has lots of advice, as well as transcribed lists of the First, Second and Third Fleets. The National Archives of Ireland has an online database of Irish convicts transported to Australia, compiled from transportation registers and petitions to government for pardon or commutation of sentence. The wonderful Proceedings of the Old Bailey London 1674–1834 website (oldbaileyonline.org) can be searched by punishment – go to the advanced search and select ‘Transportation’. Also, Australian state records include those of New South Wales’s Convict Indexes to Certificates of Freedom (1823–69).

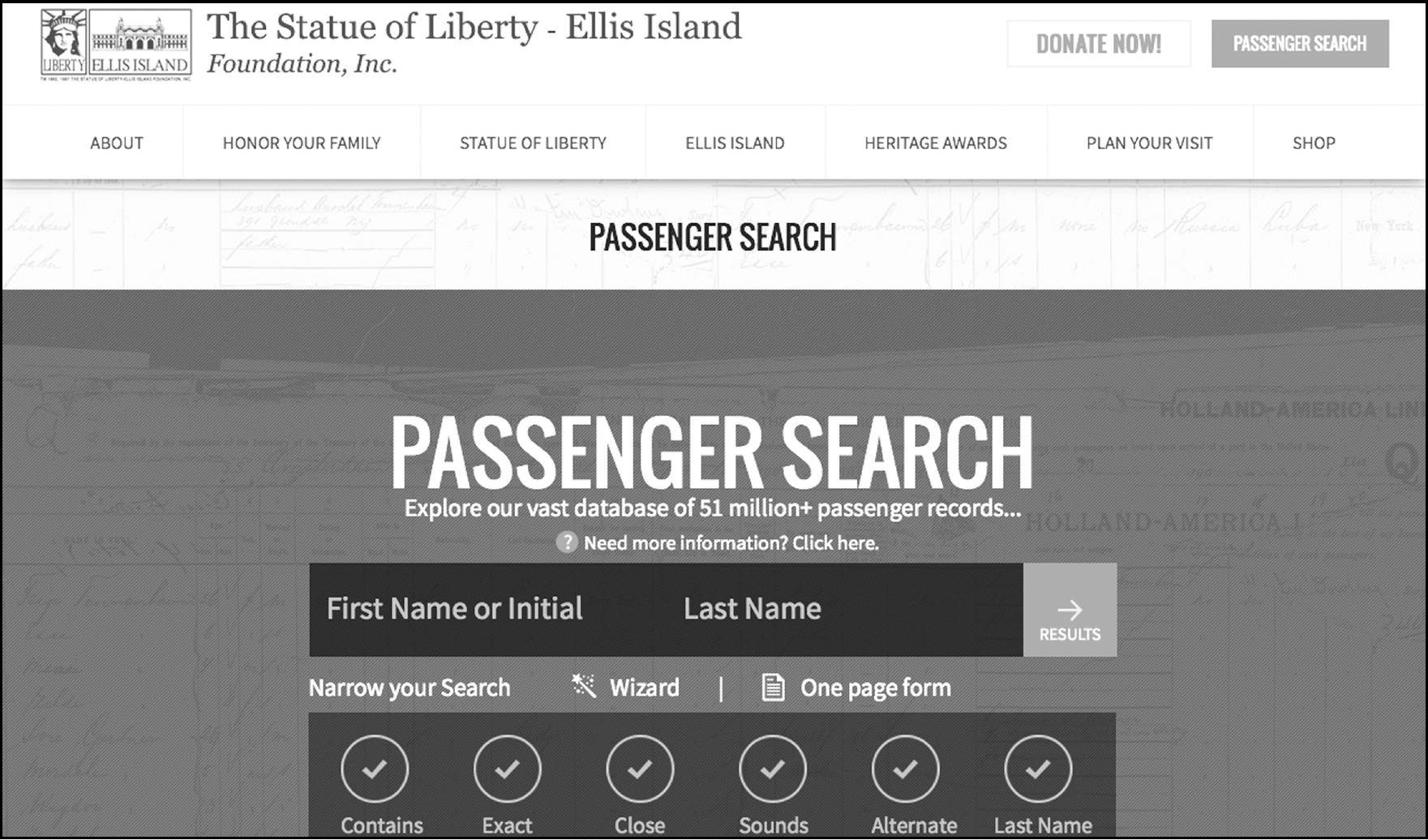

The wonderful Ellis Island Foundation website, where you can trawl a vast database of more than 51 million passenger records.

These are just some of a vast array of potential sources that may survive. But of course the next step is tracking any record of your ancestor’s arrival in their new home. For this you will need to contact and explore archives overseas. For migration to the USA, for example, there is the likes of the Ellis Island Foundation, which grants access to vast databases of arriving migrants processed at the famous Ellis Island station.

Remember to look out for societies and organisations that focus on your area of interest. The Families In British India Society (fibis.org) has an immense and very useful Wiki, with all kinds of useful advice and data for tracing family members overseas. While the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild (immigrantships.net) offers transcribed passenger lists that can be searched by port of arrival or departure. British Home Children in Canada (canadian britishhomechildren.weebly.com) has data relating to approximately 118,000 children sent to Canada from the UK under the Child Immigration scheme (1863–1939).

An important website for Irish migration research is Documenting Ireland: Parliament, People & Migration (www.dippam.ac.uk). This is a family of sites that together document Irish migration since the eighteenth century. It includes the ‘Irish Emigration Database’, based on roughly 33,000 documents – including letters, diaries and journals written by migrants, and newspaper material such as advertisements and overseas BMD notices. This really is a fascinating website, where you can spend many hours reading first-hand accounts of individuals starting new lives overseas.

The Ships List: theshipslist.com

Includes passenger lists from across the globe.

Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild: immigrantships.net

Transcribed passenger lists that can be searched by port of arrival or departure.

East India Company Ships: eicships.info/index.html

Information on ships and voyages of the East India Company’s mercantile service.

The National Archives: nationalarchives.gov.uk

There are several research guides to immigration, emigration, travel and relating to specific categories of records, such as naturalisation and passports.

On Their Own, Britain’s Child Migrants: otoweb.cloudapp.net

Child migrants to Canada, Australia and other Commonwealth countries from the 1860s to the 1960s.

England’s Immigrants Database: englandsimmigrants.com

Findmypast: findmypast.co.uk

Some important collections include Passenger Lists leaving UK (1890–1960) and Index to Register of Passport Applications (1851–1903) collections.

Ancestry: ancestry.co.uk

Has Alien Arrivals (1810–11, 1826–69), Incoming passenger lists (1878–1960), Outgoing passenger lists (1890–1960) and Aliens Entry Books (1794–1921).

TheGenealogist: thegenealogist.co.uk

Immigration/emigration collections include passenger lists and naturalisation records.

BMDregisters: bmdregisters.co.uk

Search for births, marriages and deaths on British registered ships and non-parochial registers from French, Dutch, German and Swiss churches.

British Settlers in Argentina and Uruguay: argbrit.org

London Metropolitan Archives: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/london-metropolitan-archives/Pages/default.aspx

Holds an array of resources relating to migration to London, including records for black and Asian, Irish and French migrants.

Scottish Emigration Database: abdn.ac.uk/emigration/

Records of passengers who embarked from Scottish ports between 1890 and 1960.

The Highland Clearances: highlandclearances.co.uk

Black Cultural Archives: bcaheritage.org.uk

Child Migrants Trust: childmigrantstrust.com

Black Presence in Britain: blackpresence.co.uk

India Office Family Search, British Library: indiafamily.bl.uk/UI/

National Maritime Museum: rmg.co.uk

Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain: jgsgb.org.uk

Huguenot Society: huguenotsociety.org.uk

Families In British India Society: fibis.org

Home to lots of advice for tracing family members overseas, as well as a database of nearly 1,500,000 names and the expanding Fibiwiki at wiki.fibis.org/index.php/Main_Page.

Anglo-German Family History Society: agfhs.org.uk

The National Archives of Ireland: nationalarchives.ie

Documenting Ireland, Parliament, People & Migration: dippam.ac.uk

Family of sites that draws on sources relating to Irish migration and maintains the Irish Emigration Database of letters, diaries and journals written by migrants, as well as newspaper material.

The Mellon Centre for Migration Studies, Ulster American Folk Park: www.qub.ac.uk/cms/

British Home Children in Canada: canadianbritishhomechildren.weebly.com

Library & Archives Canada: bac-lac.gc.ca/eng

Hudson Bay Company Heritage: www.hbcheritage.ca

Ellis Island: libertyellisfoundation.org

Explore the vast database of 51 million+ passenger records as well as the Immigrant Wall of Honor, a permanent exhibit of individual and family names.

Castle Garden: castlegarden.org

The pre-Ellis Island immigrant centre, Castle Garden. This provides a database of 11,000,000 names (1820–92).

US Immigrant Ancestors Project: immigrants.byu.edu

Uses emigration registers to locate information about the birthplaces of immigrants.

The National Archives of America: archives.gov

National Archives of Australia: naa.giv.au

Archives New Zealand: archives.govt.nz

Migration Heritage Australia: migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au

Convicts to Australia: members.iinet.net.au/~perthdps/convicts/

Free databases relating to transportation to Australia, including transcribed lists of the First, Second and Third Fleets.

Legacies of British Slave-ownership: ucl.ac.uk/lbs

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database: slavevoyages.org

Recovered Histories: recoveredhistories.org

Digitised eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature on the transatlantic slave trade.

Wilberforce Institute for the study of Slavery and Emancipation: www2.hull.ac.uk/fass/wise/about_us.aspx

Global Slavery Index: globalslaveryindex.org

My Slave Ancestors: myslaveancestors.com

● The last known denization was granted in 1873.

● In 1905 a new Aliens Act meant that aliens could only enter the UK at the discretion of the authorities. After 1919 they had to register with the local police.

● The main TNA record series containing information about emigrants and emigration policy are Colonial Office (CO), Home Office (HO), Board of Trade (BT) and Treasury (T).

● If you’re reading about migration you may begin to notice that anything good is the work of ‘settlers’ and ‘pioneers’, anything bad is down to ‘the British’!

● In June 1940 the Children’s Overseas Reception Board was set up to administer offers from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the USA to care for British children in private homes.

● Evacuation stopped on 17 September 1940 when the SS City of Benares was torpedoed with the loss of seventy-seven children bound for Canada.

● TNA’s Discovery catalogue also lists overseas repositories (discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/find-an-archive). Below the map of the UK you can browse by country name. It usually lists the main national archive and/or library.

Barratt, Nick. Who Do You Think You Are? Encyclopedia of Genealogy, Harper, 2008

Kershaw, Roger. Migration Records: A Guide for Family Historians, The National Archives, 2009

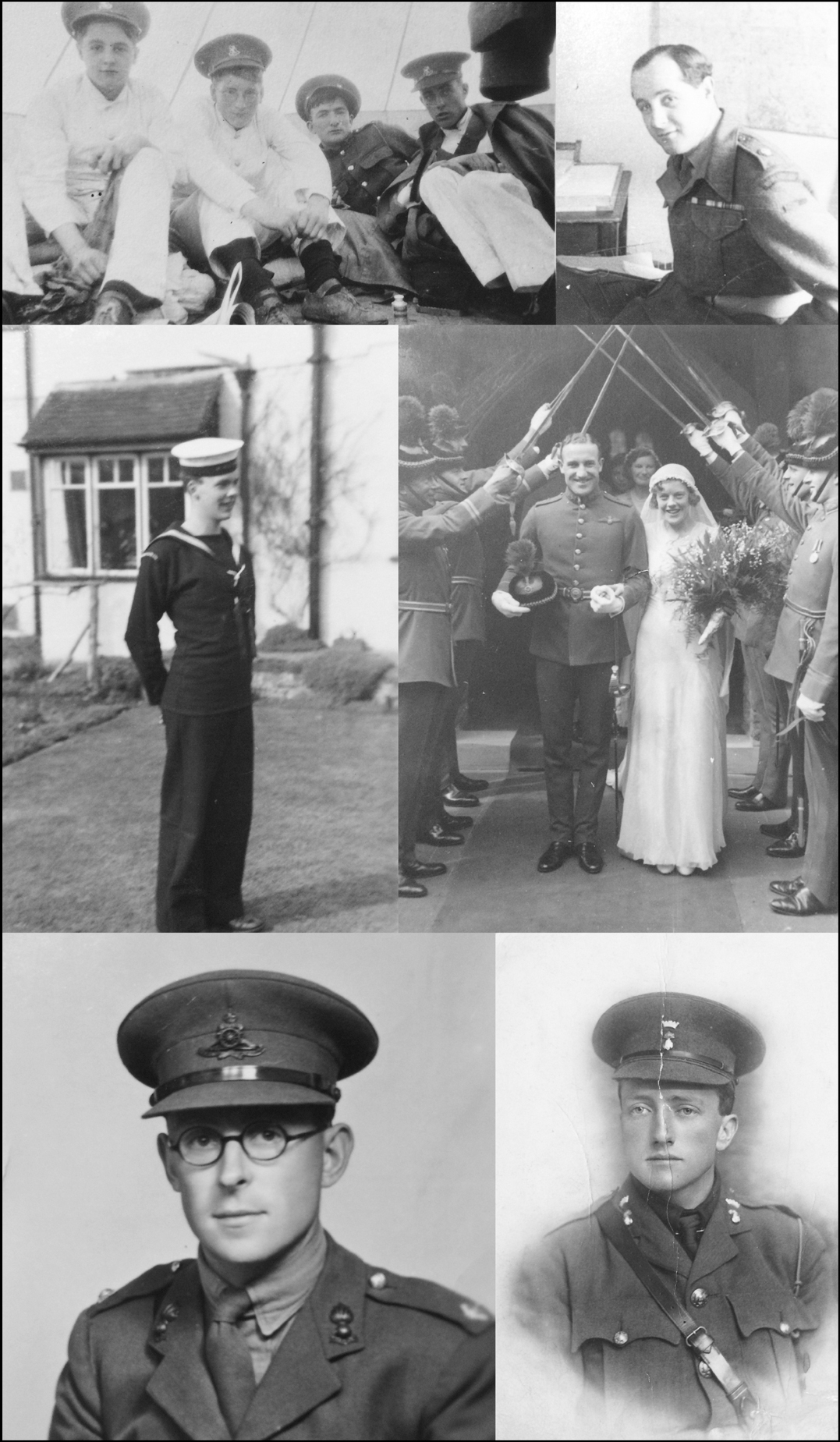

It is common to stumble upon evidence of military service in family archives, from certificates, buttons, caps, uniforms, medals and photographs to the more ephemeral stuff of family legend. My father still dines out on memories of national service: arriving as a fresh-faced youth and being mercilessly taunted for his posh accent. His old army box, labelled in chipped black paint with his rank and regiment, held my toys as a child, and, when I briefly took up coarse fishing, my weights and tackle lived in his khaki army bag.

Step back a generation, and the catalogue to the reel to reel tape collection of my paternal grandfather – full of old Goon Shows and classical radio broadcasts from the 1960s – is neatly noted down in an old Royal Air Force Signal Office Diary, the columns for ‘Watch Times’, ‘Remarks’ and ‘Signatures’ taken up with details of conductors, soloists and broadcast dates. The same grandfather was a carpenter and tinkerer, and I still play his home-made, box-shaped ukulele, constructed from whatever he could find during wartime service in Africa. My maternal grandfather served with the Royal Artillery during the Second World War. He helpfully left a modest home-bound volume of typed wartime memories, including tales of his faithful old dog Gunner Jones and his occasional association with flying ace Douglas Bader (my grandfather, not the dog).

‘He died for freedom and honour’. The memorial plaque for Kenneth Richard Scott.

Indeed, traces of both world wars pepper the walls and bookshelves of my parents’ house. Stumble over the poorly trained spaniel into their smoke-damaged kitchen, and near a wooden owl of my own construction, a painting of hands by middle-sister Kate and a sculpted clay boot by eldest sister Annabel lies a Memorial Plaque. These were issued after the First World War to the next of kin of all British and Empire service personnel killed as a result of the war. The plaques were made of bronze and became popularly known as ‘Dead Man’s Penny’. Explore the bookshelves nearby and with perseverance you will find the name of the same individual, noted down in a wonderful book of signatures compiled at a birthday ball in the early 1900s.

Let’s end our brief tour in the downstairs loo. Here, on the wall next to the throne and the guitar that can’t be tuned, is a picture of what appears to be a military inspection. In fact, it’s the future King George VI being shown a neat row of Barnardo’s children by my great-great-grandfather Sir William Fry. And just along we have a telegram from King Edward VIII (the one who abdicated), congratulating the same great-great-grandfather on his diamond wedding.

All this is meant to serve as an illustration of the kind of clues that may survive in your own archive. From the disparate items above, I can all but confirm my father’s rank and regiment, I can deduce that one grandfather served in the RAF and I have the name of another relation who lost his life in the First World War. As a starting point, it’s not bad. And if you combine all that with the ability to question living relatives, you may well have amassed a good amount of hearsay and more concrete information before you even start delving into official military sources and datasets.

This Royal Air Force Signal Office Diary was commandeered by my paternal grandfather to catalogue his reel to reel tape recordings.

There are plenty of bigger and better books that focus solely on military research for genealogists, or specific periods and conflicts. My aim here is quickly and efficiently to lay out some important facts about the military, list the main twentieth-century collections and draw attention to some of the best and most useful online resources for carrying out research remotely, for learning more about regiments, uniforms, campaign medals and more. The subject is in a sense ‘simple’ as so many important collections are preserved at TNA in Kew. But, in reality, it is rather complicated. With any military research it’s important to try to ascertain when the individual joined.

● The Royal Navy is traditionally the oldest part of the British armed forces, founded during the reign of Henry VIII, and so is known as the ‘Senior Service’.

● The navy divided its men into ratings, the name used for ordinary seaman, and officers. How much information was recorded changed over time, so an important piece of information to try to confirm is when the individual joined.

● Tracing ratings before 1853 can be difficult. One useful free tool is the Trafalgar Ancestors database (nationalarchives.gov.uk/trafalgarancestors/) which lists all those who fought in Nelson’s fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805.

● Ships’ muster and pay books (1667–1878) were essentially crew lists, and are the likeliest place to find references to ratings before 1853. You can search TNA’s Discovery catalogue for muster/pay books from a particular ship.

● Ratings records after 1853 become more detailed. The Royal Navy ratings’ service records (1853–1928) collection is available online via TNA’s website. This comprises more than 700,000 Royal Navy service records for ratings, drawn from continuous service engagement books, registers of seamen’s service and continuous record cards.

● Records of servicemen who joined after 1923 are still held by the navy. Next of kin can request a summary of a service record for an individual who joined after May 1917 from the Ministry of Defence.

● A commissioned officer was someone who became an officer by being awarded a royal commission, usually after passing an examination. These are different from warrant officers. Commissioned officers include admirals, commodores, captains, commanders and lieutenants. Warrant officers include gunners, boatswains, carpenters, ropemakers, chaplains, surgeons and engineers.

● Most nineteenth-century service records include officer’s name and rank, ships they served in as well as dates of entry/discharge from each vessel. Records can also include date of death, birth and next of kin.

● Royal Navy officers’ service records 1756–1931 are online. From series ADM 196, they include records for commissioned officers joining the navy up to 1917 and warrant officers joining up to 1931. You can search for free via Discovery and download for a fee. You can also search officers’ service record cards and files (c. 1880–1950s) and Ancestry has a Commissioned Sea Officers of the Royal Navy database.

● Ancestry has Royal Navy campaign, long service and good conduct medals – this collection includes First World War and Second World War medal and award rolls. Remember, digital microfilm copies of these records are also available to download from TNA free of charge.

● For officers you can also try Navy Lists – official published quarterly lists recording Royal Navy officers on active duty. These include rank, seniority and the ship or establishment in which the officer was serving. These are available from a number of websites, including archive.org (free of charge).

● Just as navy sources for ratings and officers can be found in different places, so there are different sources for army soldiers and officers. Soldier ranks include Private, Lance Corporal, Corporal, Sergeant and Warrant Officer. Officer ranks include Lieutenant, Captain, Major, Colonel, Brigadier and General.

● Always remember that many First World War files were lost or damaged by bombing in 1940.

● With army research it’s important to identify the individual’s military unit. If the soldier died during the world wars you can find this through the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website (cwgc.org).

● Potential army career sources include service records, casualty information, medal records and unit/operational histories. Most service records for soldiers discharged after the beginning of the First World War are with TNA, but some are held by the Ministry of Defence. Army service records for the Second World War are still with the Ministry of Defence. It does have other sources relating to the Second World War, including army casualty lists (in WO 417) which cover officers, other ranks and nurses.

● Findmypast’s important army collections include British Army Service Records (1760–1915), containing records of more than 2 million soldiers. These include ordinary soldiers and officers and were drawn from militia service records, Chelsea Pensioners service’ and discharge records, and Boer War soldiers’ documents from the Imperial Yeomanry. The site also has the 1914–20 Service Records collection, drawn from WO 363 service records and WO 364 pension records.

If you’re missing documentary evidence of an ancestor’s military career, any photographs showing uniform, cap badges or medals can provide vital clues.

● Ancestry’s army collections, also in partnership with TNA, include First World War service Records, pension records and medal rolls. Also, there’s the Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls (1793–1949) database, which contains lists of more than 2.3 million officers, enlisted personnel and other individuals entitled to medals and awards – although this particular dataset does not include First World War or Second World War medal and award rolls.

● You can search for officers’ service records (1914–22) through TNA’s catalogue. Also, for a fee, you can search campaign medal index cards (1914–20).

● Published Army Lists can also be used to trace officers’ careers. These were published monthly, quarterly and half-yearly. They list active officers and contain details of promotions.

● Records of airmen and officers of the RAF are kept in different places depending on when they served. You can also search some RAF service records via TNA’s Discovery catalogue for free. Individual image downloads cost £3.30.

● The RAF was formed in April 1918 when the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) were amalgamated. TNA’s guide to RAF personnel notes that ‘someone who served in the RFC or RNAS as well as the RAF may have service records in more than one place’. There are also research guides dedicated to both RFC officers/airmen and RNAS officers/ratings, and the Women’s Royal Air Force (WRAF).

● The RNAS was formed in 1914. You can search and download records of men who served between 1914 and 1918 via nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-naval-air-service-officers-service-records-1906-1918/.

● RAF airmen service records (not officers) between 1912 and 1939 are available on Findmypast. These include details of date/place of birth, physical description, next of kin, promotions, units and medals. The record set contains records of almost 343,000 airmen.

● Findmypast also has officer service records (1912–20), containing records of 101,266 officers, and the RAF 1918 muster roll. The former boasts records of Nobel Prizewinning author William Faulkner and W.E. Johns, creator of the fictional flying ace ‘Biggles’.

● The Battle of Britain Memorial website (battleofbritainmemorial.org) includes a database of all those who were awarded the Battle of Britain clasp.

There were various systems for mustering local forces before a Militia Act of 1757 established formal militia regiments across England and Wales. These were essentially part-time voluntary forces, organised by county and the records of conscription (between 1758 and 1831) serve as a kind of census as every year each parish was supposed to draw up lists of adult males, before holding a ballot to choose who would serve. TNA has a research guide focusing on militia, and the original lists, where they survive, are often at county archives or regimental archives. It’s also worth checking what the family history society in your area of interest has produced – you’ll often find they have published transcribed militia lists.

Many regiments look after their own collections and museums. These archives, usually accessible by appointment, may be maintained at the museum itself, or may have been deposited at the local county record office.

Even if no official regimental archive has been deposited, county archives will almost certainly have some kind of material relating to local military history. The North Yorkshire County Record Office has complete transcripts of returns of men enrolled to serve in the navy c. 1795. These relate to various North Riding wapentakes, but include men originating from all over the country. The Surrey History Centre in Woking shelters the vast Queen’s Royal Surrey Regiment archive, spanning four centuries and 45m of shelving, comprising battalion war diaries, private journals, official photograph albums and even recordings of veterans’ reminiscences.

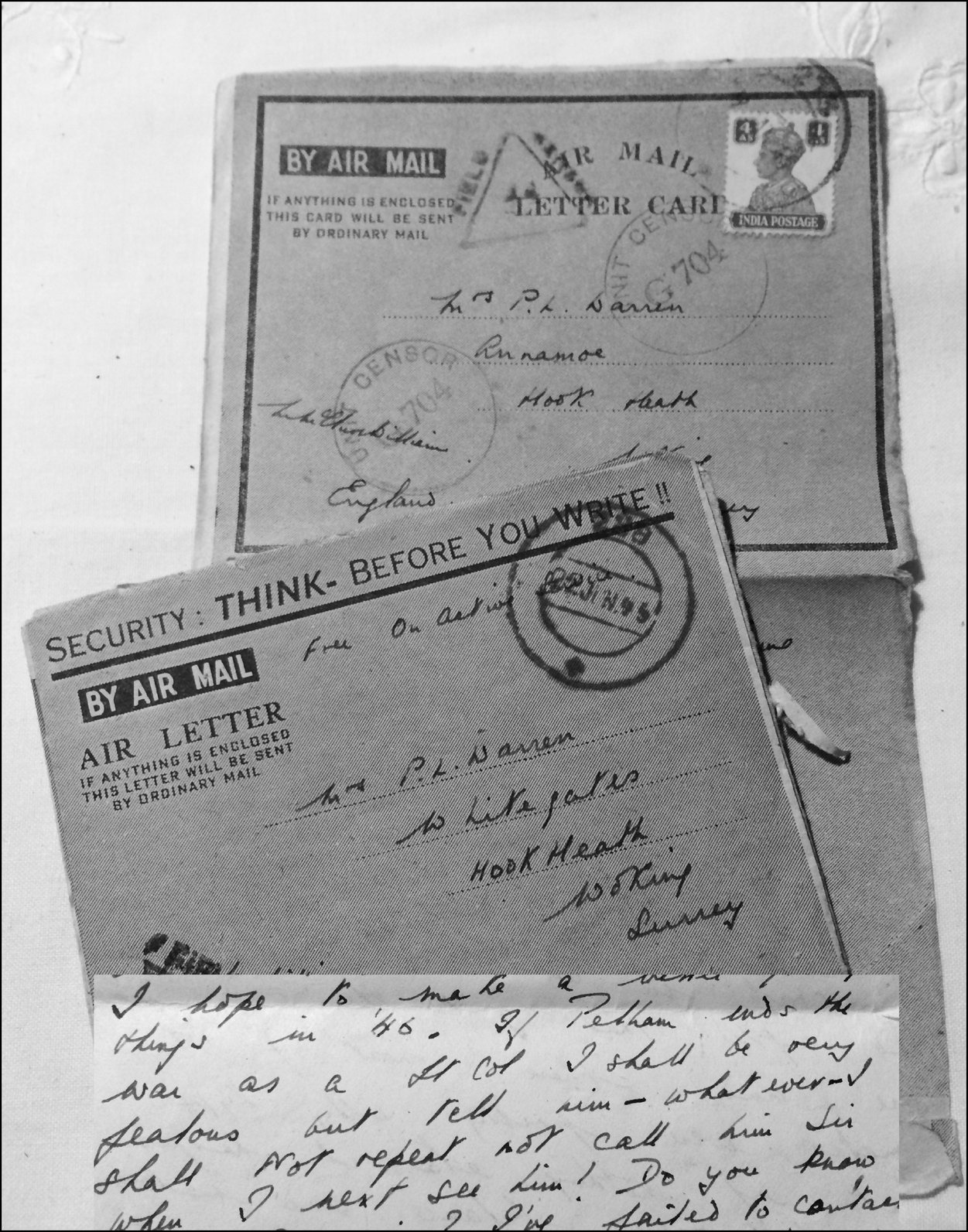

‘Security: Think – Before You Write!!’ These wartime letters contain a useful piece of information – that a relation may have ended the war with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

The museum and archives of the Prince of Wales’s Own Regiment of Yorkshire has unique historical artefacts such as the Amherst Flag, flown above the Citadel at Quebec after the Victory of the British Army led by Lord Amherst, to more practical genealogical sources such as enlistment registers, war diaries (including that of the 15th Leeds Pals Battalion, covering the first day of the Somme), photographs, personal diaries and correspondence (including the letter informing the next of kin that Private Johnson of 2nd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment, was listed as missing).

The Green Howards Regimental Museum, also in North Yorkshire, has regimental enlistment registers, detailing campaigns, wounds, medals and rewards as well as rank, ‘character’ and cause of discharge. And they have the 19th Foot regimental register of marriages and baptisms (1839–50) and a Yorkshire Regiment Punishment Book (1878–89), showing the record of a private sentenced to imprisonment and hard labour for fraudulent enlistment.

Ephemeral highlights from the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen include a postcard sent home from a Japanese POW camp by Lance Corporal Bill Angus, 2nd Battalion, The Gordon Highlanders. The entire 2nd Battalion was captured when Singapore fell to Japanese forces in February 1942. Bill was wounded by shrapnel during the battle and sent to work on the ‘Death Railway’ in Thailand. In addition, they hold the VC awarded to Captain Sir Ernest Beachcroft Beckwith Towse for two separate actions in the Boer War, the second of which blinded him.

These are just a few random examples of what can reside in regimental collections. To see if there are any that might hold information relating to your ancestor’s military career, try the Army Museums website (armymuseums.org.uk). Some museum websites have details of collections and archives, online finding aids and offer research services. Others are a bit more spartan. A great example is the website of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment (royalleicestershireregiment.org.uk), a wonderful digitised regimental archive, where you can search through over 65,000 soldier records dating back to 1688, read associated medals awards and citations, and explore digital copies of regimental journals.

Ancestry: ancestry.co.uk/military

Home to several important TNA collections such as Army Service Records (1914–20) and Naval Officer and Rating Service Records (1802–1919).

Findmypast: search.findmypast.co.uk/search-united-kingdom-records-in-military-armed-forces-and-conflict

Boasts over 12,500,000 British records relating to military service, including Royal Navy & Marine Service Records (1899–1919) and the Royal Navy Officers Medal Roll (1914–20).

Forces War Records: forces-war-records.co.uk

Specialist subscription site which has all kinds of army material that you can explore by conflict/era. Has data relating to the Royal Naval College in Dartmouth, Royal Marines and Royal Navy Officers’ Campaign Medal Rolls (1914–20), and a database of Royal Navy/Royal Marines recipients of the 1914 Star Medal. Datasets include RAF Formations List, 1918, Fighter Command Losses, 1940 and Aviators Certificates, 1905–26.

TheGenealogist: thegenealogist.co.uk

Military material includes First World War casualty lists – drawn from weekly/daily War Office lists – and a POW database.

Age of Nelson: ageofnelson.org

Hosts two useful databases – Royal Navy officers in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars (1793–1815), and the seamen and marines who fought at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

Anglo-Afghan War: garenewing.co.uk/angloafghanwar/

History of the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–80).

Army Museums: armymuseums.org.uk/ancestor.htm

Register of museums and a general introduction to researching army ancestors.

Australian War Memorial: awm.gov.au

Includes all kinds of material relating to the Australian experience of war, including centenary digitisation project ANZAC Connections and details of personnel serving in pre-First World War conflicts.

Battle of Britain Memorial: battleofbritainmemorial.org

Boer War Roll of Honour: roll-of-honour.com/Boer/

This page details the scope of the Boer Roll of Honour database. The right-hand column leads to details of UK Boer War memorials.

Bomber Command: rafbombercommand.com

History of RAF bomber aircrews, airmen and airwomen during the Second World War.

Bomber History: bomberhistory.co.uk

Has sections telling the stories of 49 Squadron, as well as specific raids and air attacks on British soil.

Britain’s Small Forgotten Wars: britainssmallwars.co.uk

British Battles: britishbattles.com

Has a number of pages covering battles from the period including details of casualties and uniforms.

British Medals Forum: britishmedalforum.com

Covers British, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, Indian, South African and all Commonwealth medals.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission: cwgc.org

Searchable database of the 1,700,000 service personnel who died during the two world wars.

Cross & Cockade International: www.crossandcockade.com

The First World War Aviation Historical Society.

Europeana 1914–1918: europeana1914-1918.eu/

Explore letters, diaries, photographs, films, documents and more through this European-wide project.

Fleet Air Arm Archive: fleetairarmarchive.net

Has a Debt of Honour Register, POW database and biographies of decorated officers.

The Gazette: thegazette.co.uk

Officers’ commissions, promotions and appointments were published in the London Gazette. You can also search and browse military awards from MiDs (mentioned in despatches) to the Victoria Cross.

Great War Forum: 1914-1918.invisionzone.com/

Forum dedicated to First World War military research.

History of RAF: rafweb.org

Imperial War Museums, Research: iwm.org.uk/research

Includes guides to tracing individuals from the army, Royal Flying Corps, RAF, Royal Navy and Merchant Navy, POWs and those involved in the home front. It’s been given a real tablet/smartphone makeover of late, with lots of blog-style articles on all kinds of subjects – including the Next of Kin Memorial Plaque (or Dead Man’s Penny) at iwm.org.uk/history/next-of-kin-memorial-plaque-scroll-and-king-s-message.

Indian Mutiny Medal Roll: search.fibis.org/frontis/bin/

Inventory of War Memorials: ukniwm.org.uk

Lives of the First World War: livesofthefirstworldwar.org

The expanding centenary crowdsourcing project ultimately aims to record as many individuals who contributed to the war effort as possible – both overseas and on the home front. Joining, browsing and uploading life stories can all be done for free, but subscribers can access various ‘premium record sets’ (available on Findmypast) and create online communities.

The Long, Long Trail: longlongtrail.co.uk

‘A site all about the soldiers, units, regiments and battles of the British Army of the First World War, and how to research and understand them.’ Its creator, Chris Baker, has a gift for explaining complicated things clearly and simply, and his brainchild is neatly designed in a way that enhances the prose. Also, he really knows his stuff. It’s simply the best place to get to grips with researching a soldier who fought in the First World War. Despite the wealth of useful information here, it never leaves you feeling overwhelmed. If you want to know how regiments, divisions, corps and units functioned, and if you want to know what life was like for soldiers and how to find out more about them, this is the place to go.

Military Archives: militaryarchives.ie

Records of Ireland’s Department of Defence, the Defence Forces and the Army Pensions Board.

Ministry of Defence: www.gov.uk/requests-for-personal-data-and-service-records

Holds records relating to soldiers who served after 1920 (other ranks) and 1922 (officers).

Napoleon Series: napoleon-series.org

Includes the Peninsular Roll Call – an index of officers who served with Wellington’s army. It was originally compiled by Captain Lionel Challis, who began working on the project soon after the First World War. Vast parent website the Napoleon Series was launched in 1995 and boasts articles, images, maps, reviews and lots more.

National Army Museum: national-army-museum.ac.uk

The place to explore army history from 1485 to date. The site has greatly improved in recent years, and you can view sample documents, photographs and prints via the Online Collection.

National Maritime Museum: collections.rmg.co.uk