“[Saul] sent men to capture [Samuel]. But when they saw a group of prophets prophesying, with Samuel standing there as their leader, the Spirit of God came on Saul’s men and they also prophesied.”

~ 1 Samuel 19:20

“Command them to do good, to be rich in good deeds, and to be generous and willing to share. In this way they will lay up treasure for themselves. . . .”

~ 1 Timothy 6:18–19

Today most universities are not even loosely a Christian institution. Religion in the university and in public life is relegated to the private experience. So-called “academic freedom” has become a sacrosanct concept and precludes anything that smacks of religiosity — especially orthodoxy that evangelicals so enthusiastically embrace. Religion is represented on campus in sanitary denominational ministries and token chapel ministries (that are hardly more than counseling centers).

To a large degree, then, the American university abandoned the evangelical and the evangelical abandoned the American university.

This created a crisis in the American university, in the evangelical community, and in American society at large. The secular American university compromised its “soul” for the naturalistic; evangelicalism compromised its epistemological hegemony for ontological supremacy. In other words, the secular university became a sort of an academic hothouse for pompous rationalism. Evangelicals abandoned the secular university, and, until recently, more or less compromised their academic base. Evangelicals even founded their own universities, but they were poor academic substitutes for secular offerings. American society no longer had spirit-filled, evangelical leaders in its leadership cadre.

Even as I write this book, this is changing.

The university, if it has any value, must be involved in the communication of immutable, metaphysical truth. The American secular university is not about to accept such limits. It recognizes no citadel of orthodoxy, no limits to its knowledge. But, like Jesus reminds Thomas in John 14, our hope lies not in what we know, but most assuredly in whom we know.

Most secular universities have concluded that abstract concepts like grace, hope, and especially faith are indefinable, immeasurable, and above all unreasonable. Not that God or the uniqueness of Jesus Christ can be proved, or disproved. There are certain issues which the order of the intellect simply cannot address, so we must rise above that to the order of the heart. Faith is our consent to receive the good that God would have for us. Evangelicals believe that God can and does act in our world and in our lives. Human needs are greater than this world can satisfy and therefore it is reasonable to look elsewhere. The university has forgotten or ignores this fact.

That is all changing — and partly due to the popularity of the American homeschooling movement. In massive numbers, the American homeschool movement — initially and presently primarily an evangelical Christian movement — is depositing some of the brightest, capable students in our country into old, august institutions like Harvard. And what is more exciting, the flashpoint of cultural change is changing from Harvard, Princeton, Darmouth, and Stanford to Wheaton, Grove City, Calvin, and Liberty (all evangelical universities). Before long the new wave of elite culture creators will be graduating from American secular universities and Christian universities and they shall be a great deal different from the elite of which I was a part in the middle 1970s. I am not saying the secular university will change quickly — intellectual naturalistic reductionism makes that extremely difficult. However, I do see the whole complexion of university graduates changing significantly in the next 20 years. Never in the history of the world has such a thing happened.

Young people, make sure that you know who you are and who your God is. “By faith, Moses, when he had grown up, refused to be known as the son of Pharaoh’s daughter” (Hebrews 11:24). Theologian Walter Brueggemann calls American believers to “nurture, nourish, and evoke a consciousness and perception alternative to the consciousness and perception of the dominant culture around us.”1

Refuse to be absorbed into the world but choose to be a part of God’s kingdom. There is no moderate position anymore in American society — either we are taking a stand for Christ in this inhospitable culture or we are not.

You are a special and peculiar generation. Much loved. But you live among a people who do not know who they are. A people without hope. You need to know who you are — children of the Living God — and then you must live a hopeful life. Quoting C.S. Lewis, we “are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea.”2

Take responsibility for your life. Moses accepted responsibility for his life. “He chose to be mistreated along with the people of God rather than to enjoy the pleasures of sin for a short time” (Hebrews 11:25). If you don’t make decisions for your life, someone else will.

Get a cause worth dying for. Moses accepted necessary suffering even unto death. You need a cause worth dying for (as well as living for). “He [Moses] regarded disgrace for the sake of Christ as of greater value than the treasures of Egypt, because he was looking ahead to his reward” (Hebrews11:26). We are crucified with Christ, yet it is not we who live but Christ who lives in us (Galatians 2:20).

Finally, never take your eyes off the goal. “By faith he left Egypt, not fearing the king’s anger; he persevered because he saw him who is invisible” (Hebrews 11:27). What is your threshold of obedience?

Young people, if you are part of this new evangelical elite, you have immense opportunities ahead of you. A new godly generation is arising. You will be called to guide this nation into another unprecedented revival. We shall see.

The Persuasive Essay

The goal of persuasion is to convince someone to adopt a position or an opinion. Read the following sermon and complete the chart.

The really good news of Isaiah 35, and of the gospel, is that as we — the chosen community, today the Church — rejoice, grow healthy, and find ourselves living in Zion, so also will the land and those who live in it find hope, health, and wholeness. Health to the Jew, as it was to the Greek, means far more than physical health. It means healing, wholeness. Indeed, the Greek word salvation has at its root the word health. We are the light of the world, and we can change our world as we share the good news. The Christ whom we represent is the only real hope the world has for wholeness. And we should be outspoken and unequivocal with this message. As we sing, with our words and our lives, the land will be saved, made whole. “Say to those with fearful hearts, ‘Be strong; do not fear.’ . . . Then the eyes of the blind be opened and the ears of the deaf unstopped” (Is. 35:4–5).

Again, this was awfully good news to a community that faced the awful King Sennacherib. King Hezekiah, Uzziah’s successor, was sorely tempted to trust in Egypt, but frankly, Isaiah in chapter 35 is making an offer that Hezekiah cannot refuse. Likewise, today, when we live a holy life, when we trust in God with faith and hope, the land in which we work and live becomes holy. In this God, of whom we bear witness with our words and lives, we, like the faithful Israelites, find wholeness, health, and life. This news is good news!

Problem__________________________________________________

Solution __________________________________________________

End result ________________________________________________

Summary Steps to Writing the ACT Essay

- Make an outline

- Use specific, not vague, abstract ideas

- State your case

- Achieve emphasis through position, statement, and proportion

- Use transitions to link your paragraphs

- Offer at least four examples

- Restate your thesis at least three times

- Summarize your argument in the conclusion

Emma3

Jane Austen

In this reader’s opinion, Emma is the best of Jane Austen. Emma, the person, defies archetypal categories. She transcends her time and place and will remain one of the most remarkable protagonists in Western literature.

Suggested Vocabulary Words

- Harriet Smith’s intimacy at Hartfield was soon a settled thing. Quick and decided in her ways, Emma lost no time in inviting, encouraging, and telling her to come very often . . . Her father never went beyond the shrubbery, where two divisions of the ground sufficed him for his long walk, or his short, as the year varied; and since Mrs. Weston’s marriage her exercise had been too much confined. (volume 1, chapter 4)

- In short, she sat, during the first visit, looking at Jane Fairfax with twofold complacency . . . that case, nothing could be more pitiable or more honourable than the sacrifices she had resolved on. Emma was very willing now to acquit her of having seduced Mr. Dixon’s actions from his wife, or of anything mischievous which her imagination had suggested at first . . . and from the best, the purest of motives, might now be denying herself this visit to Ireland, and resolving to divide herself effectually from him and his connections by soon beginning her career of laborious duty. (volume 2, chapter 2)

- As long as Mr. Knightley remained with them, Emma’s fever continued; but when he was gone, she began to be a little tranquillized and subdued — and in the course of the sleepless night . . . but she flattered herself, that if divested of the danger of drawing her away, it might become an increase of comfort to him. . . . At any rate, it would be a proof of attention and kindness in herself, from whom every thing was due; a separation for the present; an averting of the evil day, when they must all be together again. (book 3, chapter 14)

The Use of Dialogue

“I would ask you a favour,” said the German captain, as we sat in the cabin of a U-boat which had just been added to the long line of bedraggled captives which stretched themselves for a mile or more in Harwich Harbour, in November, 1918.

I made no reply; I had just granted him a favour by allowing him to leave the upper deck of the submarine, in order that he might await the motor launch in some sort of privacy; why should he ask for more?

Undeterred by my silence, he continued: “I have a great friend, Lieutenant-zu-See Von Schenk, who brought U.122 over last week; he has lost a diary, quite private, he left it in error; can he have it?”

I deliberated, felt a certain pity, then remembered the Belgian Prince and other things, and so, looking the German in the face, I said: “I can do nothing.”

“Please.”

I shook my head, then, to my astonishment, the German placed his head in his hands and wept, his massive frame (for he was a very big man) shook in irregular spasms; it was a most extraordinary spectacle.

It seemed to me absurd that a man who had suffered, without visible emotion, the monstrous humiliation of handing over his command intact, should break down over a trivial incident concerning a diary, and not even his own diary, and yet there was this man crying openly before me.

It rather impressed me, and I felt a curious shyness at being present, as if I had stumbled accidentally into some private recess of his mind. I closed the cabin door, for I heard the voices of my crew approaching.

He wept for some time, perhaps ten minutes, and I wished very much to know of what he was thinking, but I couldn’t imagine how it would be possible to find out.

I think that my behaviour in connection with his friend’s diary added the last necessary drop of water to the floods of emotion which he had striven, and striven successfully, to hold in check during the agony of handing over the boat, and now the dam had crumbled and broken away.

It struck me that, down in the brilliantly-lit, stuffy little cabin, the result of the war was epitomized. On the table were some instruments I had forbidden him to remove, but which my first lieutenant had discovered in the engineer officer’s bag.

On the settee lay a cheap, imitation leather suit-case, containing his spare clothes and a few books. At the table sat Germany in defeat, weeping, but not the tears of repentance, rather the tears of bitter regret for humiliations undergone and ambitions unrealized.

We did not speak again, for I heard the launch come alongside, and, as she bumped against the U-boat, the noise echoed through the hull into the cabin, and aroused him from his sorrows. He wiped his eyes, and, with an attempt at his former hardiness, he followed me on deck and boarded the motor launch.

Next day I visited U.122, and these papers are presented to the public, with such additional remarks as seemed desirable; for some curious reason the author seems to have omitted nearly all dates. This may have been due to the fear that the book, if captured, would be of great value to the British Intelligence Department if the entries were dated. The papers are in the form of two volumes in black leather binding, with a long letter inside the cover of the second volume.4 (Unknown, A Diary of a U-Boat Commander)

How does the narrator develop his character?

Data Analysis

Disease is the general term for any deviation from the normal or healthy condition of the body. The morbid processes that result in either slight or marked modifications of the normal condition are recognized by the injurious changes in the structure or function of the organ, or group of body organs involved. The increase in the secretion of urine noticeable in horses in the late fall and winter is caused by the cool weather and the decrease in the perspiration. If, however, the increase in the quantity of urine secreted occurs independently of any normal cause and is accompanied by an unthrifty and weakened condition of the animal, it would then characterize disease. Tissues may undergo changes in order to adapt themselves to different environments, or as a means of protecting themselves against injuries. The coat of a horse becomes heavy and appears rough if the animal is exposed to severe cold. A rough, staring coat is very common in horses affected by disease. The outer layer of the skin becomes thickened when subject to pressure or friction from the harness. This change in structure is purely protective and normal. In disease, the deviation from normal must be more permanent in character than it is in the examples mentioned above, and in some way prove injurious to the body functions.

Non-specific diseases have no constant cause. A variety of causes may produce the same disease. For example, acute indigestion may be caused by a change of diet, watering the animal after feeding grain, by exhaustion, and intestinal worms. Usually, but one of the animals in the stable or herd is affected. If several are affected, it is because all have been subject to the same condition, and not because the disease has spread from one animal to another.

Specific Diseases — The terms infectious and contagious are used in speaking of specific diseases. Much confusion exists in the popular use of these terms. A contagious disease is one that may be transmitted by personal contact, as, for example, influenza, glanders and hog cholera. As these diseases may be produced by indirect contact with the diseased animal as well as by direct, they are also infectious. There are a few germ diseases that are not spread by the healthy animals coming in direct contact with the diseased animal, as, for example, black leg and southern cattle fever. These are purely infectious diseases. Infection is a more comprehensive term than contagion, as it may be used in alluding to all germ diseases, while the use of the term contagion is rightly limited to such diseases as are produced principally through individual contact.

Parasitic diseases are very common among domestic animals. This class of disease is caused by insects and worms, as for example, lice, mites, ticks, flies, and round and flat worms that live at the expense of their hosts. They may invade any of the organs of the body, but most commonly inhabit the digestive tract and skin. Some of the parasitic insects, mosquitoes, flies and ticks, act as secondary hosts for certain animal microorganisms that they transmit to healthy individuals through the punctures or the bites that they are capable of producing in the skin.

Causes — For convenience we may divide the causes of disease into the predisposing or indirect, and the exciting or direct.

The predisposing causes are such factors as tend to render the body more susceptible to disease or favor the presence of the exciting cause. For example, an animal that is narrow chested and lacking in the development of the vital organs lodged in the thoracic cavity, when exposed to the same condition as the other members of the herd, may contract disease while the animals having better conformation do not . Hogs confined in well-drained yards and pastures that are free from filth, and fed in pens and on feeding floors that are clean, do not become hosts for large numbers of parasites. Hogs confined in filthy pens are frequently so badly infested with lice and intestinal worms that their health and thriftiness are seriously interfered with. In the first case mentioned the predisposition to disease is in the individual, and in the second case it is in the surroundings.

The exciting causes are the immediate causes of the particular disease. Exciting causes usually operate through the environment. With the exception of the special disease-producing germs, the most common exciting causes are faulty food and faulty methods of feeding. The following predisposing causes of disease may be mentioned:

Age is an important factor in the production of disease. Young and immature animals are more prone to attacks of infectious diseases than are old and mature animals. Hog-cholera usually affects the young hogs in the herd first, while scours, suppurative joint disease and infectious sore mouth are diseases that occur during the first few days or few weeks of the animal’s life. Lung and intestinal parasites are more commonly found in the young, growing animals. Old animals are prone to fractures of bones and degenerative changes of the body tissues. As a general rule, the young are more subject to acute diseases and the old to chronic diseases.

The surroundings or environments are important predisposing factors. A dark, crowded, poorly ventilated stable lowers the animal’s vitality, and renders it more susceptible to the disease. A few rods difference in the location of stables and yards may make a marked difference in the health of the herd. A dry, protected site is always preferable to one in the open or on low, poorly drained soil. The majority of domestic animals need but little shelter, but they do need dry, comfortable quarters during wet, cold weather.

Faulty feed and faulty methods of feeding are very common causes of diseases of the digestive tract and the nervous system. A change from dry feed to a green, succulent ration is a common cause of acute indigestion in both horses and cattle. The feeding of a heavy ration of grain to horses that are accustomed to exercise, during enforced rest may cause liver and kidney disorders. The feeding of spoiled, decomposed feeds may cause serious nervous and intestinal disorders.

One attack of a certain disease may influence the development of subsequent attacks of the same, or a different disease. An individual may suffer from an attack of pneumonia that so weakens the disease-resisting powers of the lungs as to result in a tubercular infection of these organs. In the horse, one attack of azoturia predisposes it to a second attack. One attack of an infectious disease usually confers immunity against that particular disease. Heredity does not play as important a part in the development of diseases in domestic animals as in the human race. A certain family may inherit a predisposition to disease through the faulty or insufficient development of an organ or group of organs. The different species of animals are affected by diseases peculiar to that particular species. The horse is the only species that is affected with azoturia. Glanders affects solipeds, while black leg is a disease peculiar to cattle.5

- What is disease?

- What is a predisposing cause? Exciting cause?

The Writing Test

The writing test is a 30-minute essay test that measures your writing skills. The test consists of one writing prompt that will define an issue and describe two points of view on that issue. You are asked to respond to a question about your position on the issue described in the writing prompt. In doing so, you may adopt one or the other of the perspectives described in the prompt, or you may present a different point of view on the issue. Your score will not be affected by the point of view you take on the issue. One word of caution: in my opinion, it would be injudicious to tell your grader that you are a homeschooler or that you are a born-again Christian. My impressions are that such appellations inevitably evoke negative responses.

- Carefully read the instructions on the cover of the test booklet.

- Mark up the prompt and write an outline.

- Do not skip lines and do not write in the margins. Write your essay legibly, in English. Remember: longer is always better.

- If possible, discuss the issue in a broader context or evaluate the implications or complications of the issue.

- Address what others might say to refute your point of view and present a counterargument. This is critical and different from the SAT.

- Use specific examples. Do not write in generalities.

- Vary the structure of your sentences, and use varied and precise word choices. Make logical relationships clear by using transitional words and phrases.

- Stay focused on the topic. Mention your thesis multiple times.

- End with a strong conclusion that summarizes or reinforces your position. Correct any mistakes in grammar, usage, punctuation, and spelling. Write legibly.

“The person, be it gentleman or lady, who has not pleasure in a good novel, must be intolerably stupid.”6

— Jane Austen

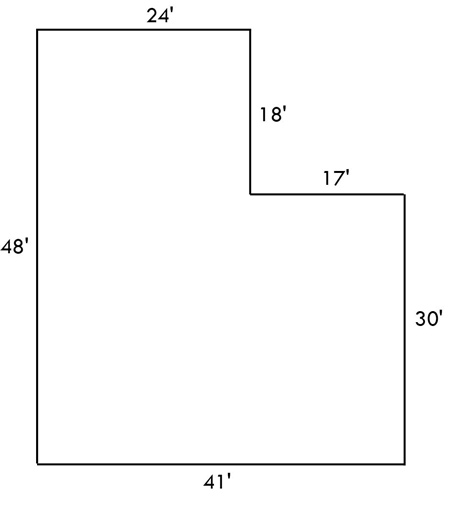

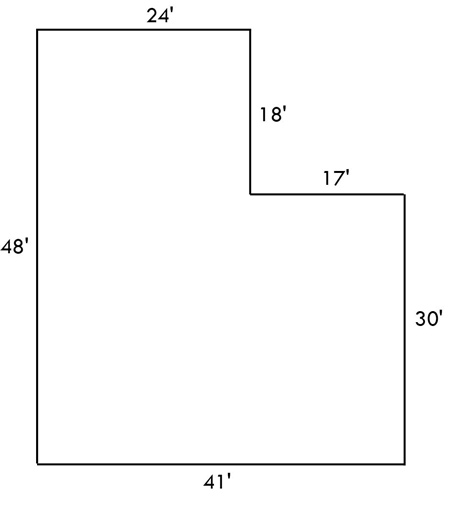

Word Problem

What is the total square footage of this house?

Writing with Sensory Words

Write with words that appeal to the senses.

Write a short essay describing a time when you ate an ice cream cone. Use at least 5 words from the list below.

|

Sight Words

|

Audible Words

|

Sensory/Touch Words

|

Taste/Smell Words

|

|

ample

|

smash

|

chilly

|

fruity

|

|

drab

|

yelp

|

oily

|

rancid

|

|

disheveled

|

jarring

|

slippery

|

flowery

|

|

hilarious

|

hiss

|

frigid

|

musty

|

|

scrawny

|

clanging

|

clammy

|

zesty

|

Go to Answers Sheet