“The Lord your God is with you, he is mighty to save. He will take great delight in you, he will quiet you with his love, he will rejoice over you with singing.”

~ Zephaniah 3:17

“So that you may become blameless and pure, children of God without fault in a crooked and depraved generation, in which you shine like stars in the universe.”

~ Philippians 2:15

My life closed twice before its close; It yet remains to see

If Immortality unveil A third event to me,

So huge, so hopeless to conceive, As these that twice befell.

Parting is all we know of heaven, And all we need of hell.1

Emily Dickinson uses the metaphor of death to describe the catastrophe that two terrible events caused. Were these the deaths of two friends? Two unrequited loves? We really don’t know. What matters is that the pain of these events was so sharp that Dickinson feels as if her life ended. Loss exacerbates Dickinson’s already fragile metaphysics.

What happens after death, in immortality? Well we know, don’t we?

The last two lines of this poem present a powerful paradox; parting is heaven to some and hell to others. We part with those who die and — hopefully — go to heaven, which is, ironically, an eternal happiness for them; however, we who are left behind suffer the pain (hell) of their deaths (parting).

Is there any comfort in this poem? Not if one is the realist Emily Dickinson whose cold New England intellectualism offers scant protection against the frigid exigencies of death! It is fun to talk about birds walking on sidewalks as long as one does not have to think about ultimate things.

But we all have to think about ultimate things once in a while. In “a while” for most of us is death. Where will you spend eternity? If the Lord Jesus is your Savior, you know where you will spend eternity.

Contrast this tentativeness with Dickinson’s New England predecessor Puritan Edward Taylor (From “I Prepare a Place”):

But thats not all: Now from Deaths realm, erect,

Thou gloriously gost to thy Fathers Hall:

And pleadst their Case preparst them place well dect

All with thy Merits hung. Blesst Mansions all.

Dost ope the Doore locks fast ‘gainst Sins that so

These Holy Rooms admit them may thereto.2

I like to read Emily Dickinson’s poems. I like to drink vanilla milk shakes, too. But not too many and never for nourishment and life. How about you?

“Life like a dream is lived alone . . .” (Marlow in Heart of Darkness).3 I know someone who believes that to be true. One of my students rarely speaks. Indeed, he seems virtually unable to do anything. He is frozen in time. Last year he tried to commit suicide. Thankfully, he failed. When he was driving home from the hospital with his obviously irritated mom, this young man sat sullen and broken. His mom, furious, stopped the car, looked at her son, opened the car pocket and said, “Here is a loaded gun, finish the job.”

Thankfully, my poor student could not finish the job; but the loss of trust he experienced more or less ended his life as he knew it. Over the next year, slowly, steadily he made progress. Finally, thanks to the love of a young lady, the young man has blossomed! Life like a dream is lived alone. . . . But in those magical moments when a friend, a spouse, a kindred spirit joins us — we experience hope and life.

No one likes to be on the losing side — unless one is breaking up a fight in public high school. We teachers are taught, when breaking up a fight, to hold the losing student — why? Because the losing student wants an excuse to quit. You give him the excuse. Well, I chose the winning side last week and it nearly killed me! I rushed from in front of my door to break up a fight. I go to the doctor tomorrow to see how much damage the winner did to my artificial hip. Life is like that, isn’t it? We find sometimes that grabbing the losing cause can bring us winning. Think about it.

Through the Iron Bars4

Emile Cammaerts

Every war causes excesses and atrocities, but World War I created more than its share. In particular, as Germany rushed across the lowlands of neutral Belgium to conquer France, it subjugated Belgium and occupied it as an unfriendly government for the next four years. There is much debate about how bad the Germans really were, but propaganda, among the allies, was magnificent.

Suggested Vocabulary Words

A. The German occupation of Belgium may be roughly divided into two periods: Before the fall of Antwerp, when the hope of prompt deliverance was still vivid in every heart and when the German policy, in spite of its frightfulness, had not yet assumed its most ruthless and systematic character; and after the fall of the great fortress, when the yoke of the conqueror weighed more heavily on the vanquished shoulders and when the Belgian population, grim and resolute, began to struggle to preserve its honour and loyalty and to resist the ever increasing pressure of the enemy to bring it into complete submission and to use it as a tool against its own army and its own King.

B. I am only concerned here with the second period. The story of the German atrocities committed in some parts of the country at the beginning of the occupation is too well known to require any further comment. Every honest man, in Allied and neutral countries, has made up his mind on the subject. No unprejudiced person can hesitate between the evidence brought forward by the Belgian Commission of Enquiry and the vague denials, paltry excuses and insolent calumnies opposed to it by the German Government and the Pro-German Press.

C. Besides, in a way, the atrocities committed during the last days of August 1914 ought not to be considered as the culminating point of Belgium’s martyrdom. They have, of course, appealed to the imagination of the masses, they have filled the world with horror and indignation, but they did not extend all over the country, as the present oppression does; they only affected a few thousand men and women, instead of involving hundreds of thousands.5

Graphs

Solve graphically:

1. x2 – 5x + 4 = 0

2. x2 + 5x + 4 = 0

3. x2 + 5x – 4 = 0

4. x2 – 5x – 4 = 0

5. x2 – 4x + 4 = 0

Active Voice

Always write in active voice. Change the passive voice sentences to active voice sentences.

1. In the large room some forty or fifty students were walking about while the parties were preparing.

2. This was done by taking off the coat and vest and binding a great thick leather garment on, which reached to the knees.

3. We were joined by the crowd, and used our lungs as well as any.6

“The worst thing about new books is that they keep us from reading the old ones.”7

— Joseph Joubert

Calculations

The following is a chart of tidal levels after sunset (and as the moon rises):

Hour of moon’s transit after sunset:

|

0

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

Tidal position:

|

0

|

-20m

|

-30m

|

-50m

|

-60m

|

-60m

|

-60m

|

-40m

|

-10m

|

+10m

|

+20m

|

+10m

|

If sunset is 5:45 p.m., and at that time the tide is at X m, what is the approximate tidal level at 11 p.m.?

A. -60m

B. -35m

C. -65m

D. +10m

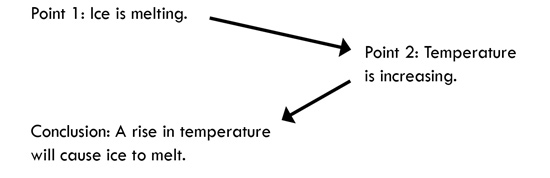

Science Test Musings

Mark it up! Make notes in your test booklet to help you answer the questions. Draw pictures to help you understand the information (below). Underline or circle key points.

Since you cannot use a calculator on the science test, be sure to do correct math calculations. Unless it’s an extremely easy math calculation, use your test booklet to do the math. One ACT coach reminds us, “The science test comes at the end, and you will be tired — it’s easy to make a careless error at this point.”

Writing Style

Which part of the sentence below is wrong?

His (A) bravery during this painful operation and the (B) fortitude he had shown in heading the last charge in the recent action (C); though, he was wounded at the time and had been unable to use his right arm, and was the only officer left in his regiment, out of twenty who were alive the day before, (D) inspired every one with admiration.

Credibility

By the Waters of Babylon . . .

“By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.”

What prophetic spirit inspired Cardinal Mercier when he chose this psalm for the text of his sermon, on the occasion of the second anniversary of their Independence (July 21st, 1916), which the Belgians celebrated in exile and captivity? It was in the great Gothic church, in Brussels, under the arches of Ste. Gudule, at the close of a service for the soldiers fallen during the war, the very last patriotic ceremony tolerated by the Germans. Socialists, Liberals, Catholics crowded the nave, forgetting their old quarrels, united in a common worship, the worship of their threatened country, of their oppressed liberties.

“How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” His audience imagined that the preacher alluded only to a spiritual captivity, that he meant: “How shall we celebrate our freedom in this German prison?” And they listened, like the first Christians in the catacombs, dreading to hear the tramp of the soldiers before the door. The Cardinal pursued his fearless address: “The psalm ends with curses and maledictions. We will not utter them against our enemies. We are not of the Old but of the New Testament. We do not follow the old law: an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth, but the new law of Love and Christian brotherhood. But we do not forget that even above Love stands Justice. If our brother sins, how can we pretend to love him if we do not wish that his sins should be punished. . . .

Such was the tenor of the Cardinal’s address, the greatest Christian address inspired by the war, uttered under the most tragic and moving circumstances. For the people knew by then the danger of speaking out their minds in conquered Belgium; they knew that some German spies were in the church taking note of every word, of every gesture. Still, they could not restrain their feelings, and, at the close of the sermon, when the organ struck up the Brabançonne, they cheered and cheered again, thankful to feel, for an instant, the dull weight of oppression lifted from their shoulders by the indomitable spirit of their old leader.

What strikes us now, when recalling this memorable ceremony, is not so much the address itself as the choice of its text: “For they that carried us away captive required of us a song.”

Many of those who listened to Cardinal Mercier on July 21st, 1916, have no doubt been “carried away” by now, and they have sung. They have sung the Brabançonne and the “Lion de Flandres” as a last defiance to their oppressors whilst those long cattle trains, packed with human cattle, rolled in wind and rain towards the German frontier. And the echo of their song still haunts the sleep of every honest man.8

How does the author influence the reader?

- By using facts.

- By referencing an emotive scriptural passage

- By using archetypical villain types

- By offering pejorative motifs

- I

- II

- III

- IV

- None

- All

- I and IV

- II, III, and IV

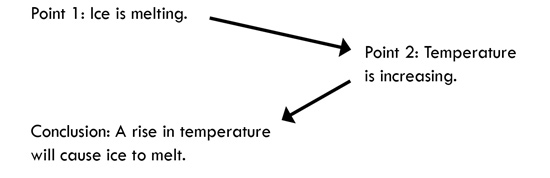

How does the author influence the reader through this picture?

- By using facts.

- By referencing an emotive scene; a man attacking a child

- By using caricatures

- By offering pejorative motifs

- By appealing to religion

- I

- II

- III

- IV

- V

- All

- I, II, IV, V

- II, III, and IV

Go to Answers Sheet