“So then, just as you received Christ Jesus as Lord, continue to live in him rooted and built up in him, strengthened in the faith as you were taught, and overflowing with thankfulness.”

~ Colossians 2:6–7

“They will make war against the

Lamb, but the Lamb will overcome them because he is Lord of lords and King of kings — and with him will be his called, chosen and faithful followers.”

~ Revelation 17:14

Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a story of a histrionic English official named Marlowe who visits the most uncivilized parts of late 19th-century Africa to discover what happened to an erudite, arcane English station chief named Kurtz. The journey is nothing less than a naturalistic journey into the human soul. We journey deeper and deeper into the heart of darkness. It was very quiet there.

Marlowe comments, “At night sometimes the roll of drums behind the curtain of trees would run up the river and remain sustained faintly, as if hovering in the air high over our heads, till the first break of day. Whether it meant war, peace, or prayer we could not tell. The dawns were heralded by the descent of a chill stillness; the wood-cutters slept, their fires burned low; the snapping of a twig would make you start. We were wanderers on a prehistoric earth, on an earth that wore the aspect of an unknown planet. We could have fancied ourselves the first of men taking possession of an accursed inheritance, to be subdued at the cost of profound anguish and of excessive toil. But suddenly, as we struggled round a bend, there would be a glimpse of rush walls, of peaked grass-roofs, a burst of yells, a whirl of black limbs, a mass of hands clapping, of feet stamping, of bodies swaying, of eyes rolling, under the droop of heavy and motionless foliage. The steamer toiled along slowly on the edge of a black and incomprehensible frenzy. The pre-historic man was cursing us, praying to us, welcoming us — who could tell? We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. We could not understand because we were too far and could not remember because we were travelling in the night of first ages, of those ages that are gone, leaving hardly a sign — and no memories.”1

Kurtz, apparently has gone off the deep end — he has, in effect, given into his “darker side” and become a savage. The irony in this turn of events is obvious: Kurtz, the civilized man seeking to civilize the savage, becomes, instead, a savage himself. Poor Kurtz, full of hope and faith, has lost it all. “One evening coming in with a candle I was startled to hear him say a little tremulously, ‘I am lying here in the dark waiting for death.’ The light was within a foot of his eyes. I forced myself to murmur, ‘Oh, nonsense!’ and stood over him as if transfixed.” Anything approaching the change that came over his features I have never seen before, and hope never to see again. Oh, I wasn’t touched. I was fascinated. It was as though a veil had been rent. I saw on that ivory face the expression of sombre pride, of ruthless power, of craven terror — of an intense and hopeless despair. Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation, and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge? He cried in a whisper at some image, at some vision — he cried out twice, a cry that was no more than a breath: “‘The horror! The horror!’ The horror! The horror!”2

Poor Kurtz. Poor 21st-century America. They (we) have looked into the abyss, and we see no loving God. What is the horror to Kurtz? He has lost his faith in a loving God. His world is a naturalistic, impersonal, cruel jungle. “I thought his memory was like the other memories of the dead that accumulate in every man’s life — a vague impress on the brain of shadows that had fallen on it in their swift and final passage; but before the high and ponderous door, between the tall houses of a street as still and decorous as a well-kept alley in a cemetery, I had a vision of him on the stretcher, opening his mouth voraciously, as if to devour all the earth with all its mankind. He lived then before me; he lived as much as he had ever lived — a shadow insatiable of splendid appearances, of frightful realities; a shadow darker than the shadow of the night, and draped nobly in the folds of a gorgeous eloquence. The vision seemed to enter the house with me — the stretcher, the phantom-bearers, the wild crowd of obedient worshippers, the gloom of the forests, the glitter of the reach between the murky bends, the beat of the drum, regular and muffled like the beating of a heart — the heart of a conquering darkness. It was a moment of triumph for the wilderness, an invading and vengeful rush which, it seemed to me, I would have to keep back alone for the salvation of another soul. And the memory of what I had heard him say afar there, with the horned shapes stirring at my back, in the glow of fires, within the patient woods, those broken phrases came back to me, were heard again in their ominous and terrifying simplicity. I remembered his abject pleading, his abject threats, the colossal scale of his vile desires, the meanness, the torment, the tempestuous anguish of his soul. And later on I seemed to see his collected languid manner, when he said one day, ‘This lot of ivory now is really mine. The Company did not pay for it. I collected it myself at a very great personal risk. I am afraid they will try to claim it as theirs though. H’m. It is a difficult case. What do you think I ought to do — resist? Eh? I want no more than justice.’ . . . He wanted no more than justice — no more than justice. I rang the bell before a mahogany door on the first floor, and while I waited he seemed to stare at me out of the glassy panel — stare with that wide and immense stare embracing, condemning, loathing all the universe. I seemed to hear the whispered cry, ‘The horror! The horror!’ ”3

My friends, brothers, and sisters, I have looked into the abyss and I see a God. A real, loving God. A God who loved the world so much that He sent His only begotten Son. Do you? To the naturalist, as Marlow muttered, life like a dream is lived alone. To a Christian, there is life, and life more abundant than we can imagine!

Usage: Shall and Will

Traditionally, shall is used for the future tense with the first-person pronouns I and we: I shall, we shall. Will is used with the first-person (again, I refer to traditional usage) only when we wish to express determination. The opposite is true for the second-person (you) and third-person (he, she, it, they) pronouns: Will is used in the future tense, and shall is used only when we wish to express determination or to emphasize certainty.

Although this is the traditional distinction between shall and will, many linguists and grammarians have challenged this rule, and it is often not observed, even in formal writing. Personally, I still try to remember to follow it, even though the use of shall seems to be declining.

Here are some examples, applying the traditional rule.

First-person pronouns:

I shall attend the meeting. (Simple future tense)

I will attend the meeting. (Simple future tense but with an added sense of certainty or determination)

Regardless of the weather, we shall go to the city. (Simple future tense)

Regardless of the weather, we will go to the city. (Simple future tense but with an added sense of certainty or determination)

Second-person pronoun:

You will receive a refund. (Simple future tense)

You shall receive a refund. (Simple future tense but with an added sense of certainty or determination)

Third-person pronoun:

It will be done on time. (Simple future tense)

It shall be done on time. (Simple future tense but with an added sense of certainty or determination)

Will is usually the better choice with second- and third-person pronouns. If we wish to express certainty or determination, we do not need to use shall but can provide emphasis by using an adverb, such as certainly or definitely. However, the distinction between shall and will that I mention above is useful with first-person pronouns.4

Examine the following sentences, and justify the use of shall and will, or correct them if wrongly used:

1. Thou shalt have a suit, and that of the newest cut; the wardrobe keeper shall have orders to supply you.

2. “I shall not run,” answered Herbert stubbornly.

An idiom is a phrase whose meaning is not immediately apparent from the meanings of its individual words. Occasionally the ACT will include some idioms that you will need to interpret in the context of the reading passage. For example, “Watching my grandchildren was no effort to the eye” means “watching my grandchildren was easy, even pleasant.”

Math Test Breakdown

Arithmetic: 20%

Basic Math — Definitions and Principles

Variable Linear Equations

Signed Numbers/Absolute Value

Averages

Multiples and Factors

Ordering Numbers

Percents

Probability

Proportions

Ratios

Powers and Roots

Substitution

Factoring Quadratic Equations

Beginning Algebra: 20%

Polynomials

Variables to Relationships

Linear Equations

Exponents

Tables/Charts/Graphs

Complex Numbers

Functions

Inequalities

Matrices

Quadratic Inequalities

Quadratic Formula

Systems of Equations

Coordinate Geometry: 30%

Rational Expressions

Solving Radical Equations

Distance and Midpoint

Conic Sections

Equations of Lines

Parallel and Perpendicular Lines

Number Line/Coordinate Plane

Sequences and Series

Right Triangles

Trigonometry

Plane Geometry: 30%

Polygons

Area/Perimeter/Volume

Analyzing Data

I have said that the entire Mafula community is for many purposes a composite whole. In many matters they act together as a community. This is especially so as regards the big feast, which I shall describe hereafter. It is so also to a large extent in some other ceremonies and in the organisation of hunting and fishing parties and sometimes in fighting. And the community as a whole has its boundaries, within which are the general community rights of hunting, fishing, etc., as above stated.

But the relationship between a group of villages of any one clan within the community is of a much closer and more intimate character than is that of the community as a whole. These villages of one clan have a common amidi or chief, a common emone or clubhouse, and a practice of mutual support and help in fighting for redress of injury to one or more of the individual members; and there is a special social relationship between their members, and in particular clan exogamy prevails with them, marriages between people of the same clan, even though in different villages, being reprobated almost as much as are marriages between people of the same village. Nonetheless, the clans separate in village settings.5 (Williason, The Mafula)

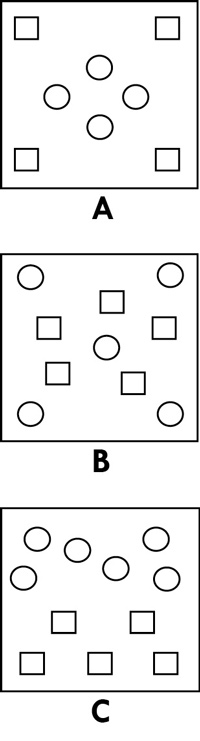

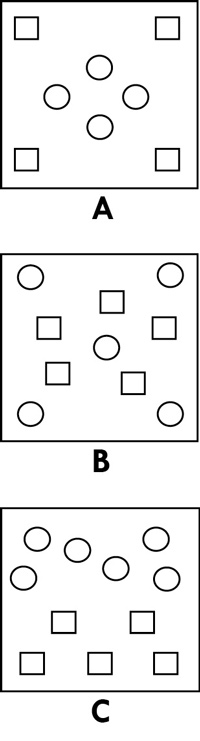

Which of the following diagrams best represents what a Mafula village looks like?

The Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture6

Matthew Holbeche Bloxam

Amongst the vestiges of antiquity which abound in this country, are the visible memorials of those nations which have succeeded one another in the occupancy of this island. To the age of our Celtic ancestors, the earliest possessors of its soil, is ascribed the erection of those altars and temples of all but primeval antiquity, the Cromlechs and Stone Circles which lie scattered over the land; and these are conceived to have been derived from the Phoenicians, whose merchants first introduced amongst the aboriginal Britons the arts of incipient civilization. Of these most ancient relics the prototypes appear, as described in Holy Writ, in the pillar raised at Bethel by Jacob, in the altars erected by the Patriarchs, and in the circles of stone set up by Moses at the foot of Mount Sinai, and by Joshua at Gilgal. Many of these structures, perhaps from their very rudeness, have survived the vicissitudes of time, whilst there scarce remains a vestige of the temples erected in this island by the Romans; yet it is from Roman edifices that we derive, and can trace by a gradual transition, the progress of that peculiar kind of architecture called Gothic, which presents in its later stages the most striking contrast that can be imagined to its original precursor.

The Romans having conquered almost the whole of Britain in the first century, retained possession of the southern parts for nearly four hundred years; and during their occupancy they not only instructed the natives in the arts of civilization, but also with their aid, as we learn from Tacitus, began at an early period to erect temples and public edifices, though doubtless much inferior to those at Rome, in their municipal towns and cities. The Christian religion was also early introduced, but for a time its progress was slow; nor was it till the conversion of Constantine, in the fourth century, that it was openly tolerated by the state, and churches were publicly constructed for its worshippers; though even before that event, as we are led to infer from the testimony of Gildas, the most ancient of our native historians, particular structures were appropriated for the performance of its divine mysteries: for that historian alludes to the British Christians as reconstructing the churches which had, in the Dioclesian persecution, been levelled to the ground.7

Define the suggested vocabulary words underlined in the above passage.

Details

The churches of this country were anciently so constructed as to display, in their internal arrangement, certain appendages designed with architectonic skill, and adapted purposely for the celebration of mass and other religious offices.

At the Reformation, when the ritual was changed and many of the formularies of the church of Rome were discarded, some of such appendages were destroyed; whilst others, though suffered to exist, more or less in a mutilated condition, were no longer appropriated to the particular uses for which they had been originally designed.

On entering a church through the porch on the north or south side, or at the west end, we sometimes perceive on the right hand side of the door, at a convenient height from the ground, often beneath a niche, and partly projecting from the wall, a stone basin: this was the stoup, or receptacle for holy water, called also the aspersorium, into which each individual dipped his finger and crossed himself when passing the threshold of the sacred edifice. The custom of aspersion at the church door appears to have been derived from an ancient usage of the heathens, amongst whom, according to Sozomen, the priest was accustomed to sprinkle such as entered into a temple with moist branches of olive. The stoup is sometimes found inside the church, close by the door; but the stone appendage appears to have been by no means general, and probably in most cases a movable vessel of metal was provided for the purpose; and in an inventory of ancient church goods at St. Dunstan’s, Canterbury, taken A.D. 1500, we find mentioned “a stope off lede for the holy watr atte the church dore.” We do not often find the stoup of so ancient a date as the twelfth century; one much mutilated, but apparently of that era, may however be met with inside the little Norman church of Beaudesert, Warwickshire, near to the south door.

The porch was often of a considerable size, and had frequently a groined ceiling, with an apartment above; it was anciently used for a variety of religious rites, for before the Reformation considerable portions of the marriage and baptismal services, and also much of that relating to the churching of women, were here performed, being commenced “ante ostium ecclesiae,” and concluded in the church; and these are set forth in the rubric of the Manual or service-book, according to the use of Sarum, containing those and other occasional offices.8 (Bloxam)

The porch was very large in early pre-Reformation English churches because:

- in Roman Catholic liturgy considerable portions of the marriage and baptismal services occur on the porch.

- the porch reminds the congregant of the Temple of Solomon.

- the porch offered a more comfortable, generous feeling to the worship participants.

- the porch was a convention important to early Roman architecture.

Some ACT test takers use their wrist watches as a stop watch, not as a time piece. For example, if they have a 45 minute test they set their watch at 45 minutes. Caution: turn off the alarm!

Geometric Word Problems

A stream flows at the rate of a miles an hour, and a man can row in still water b miles an hour. How far can the man row up the stream in an hour? In six hours? How far down the stream in an hour? In three hours?

Writing Style

Which part of the sentence below is wrong?

When I say a great man, I not (A) only mean a man intellectually great but also morally, (B) who has no preference for diplomacy at all events which is mean, petty, and underhanded to secure ends which can be secured by an honest policy equally (C) good, who prefers to get at truth by untruthful tricks, and (D) who considers truth a carp which is to be caught by the bait falsehood. We cannot call a petty intriguer great, though we may be forced to call an unscrupulous man by that name.

Go to Answers Sheet