THIRTY-TWO

I awoke in a hospital room, with Pepper leaning over the bed.

“He’s awake,” she said, and I heard a familiar voice say, “Thank God.”

Esme appeared on the other side of the bed, Shelby Deeds looking over her shoulder.

“You’ve had a nice sleep, young man,” the old historian said. “About time to get up and get back to work.”

The door flew open and Sam MacGregor barged in, trailing a protesting nurse.

“He’s my son. You can’t keep me away. It’s a matter of life and—oh, hello, Shelby. Alan, I was in the Rockies and heard you were dead.”

“Exaggeration.”

“That’s a relief.” Sam reached under his jacket, brought out a bottle of J. W. Dant, unscrewed the cap, and took a long pull.

“Now I feel better.”

“You can’t bring that in here,” the rotund nurse warned, but Sam shushed her. “Go away. You’re interrupting a religious observance.”

“Somebody want to tell me what happened?” I asked.

“There are people in the hallway,” the nurse protested. “There’s a man with long hair sitting cross-legged on the floor and there’s somebody with tattoos and—”

“Call security,” Sam ordered. “The situation sounds desperate.”

“Alan, what’s going on?” David Goldman was in the room now, his sweat-stained T-shirt emitting an aroma that sent all heads in his direction. “I just came up from the Basin. Marilyn said you were dead.”

“I wish,” I groaned.

“Here,” Sam said, handing me the bottle. “This will help.”

I pushed the bottle away.

“The missing page …”

Pepper held up a piece of paper. “Do you believe in divine intervention?”

“What?”

“It’s her way of telling you the damn thing was in the Bible,” Sam said. “Nothing divine about it.”

“When the door to the bedroom opened I saw the Bible lying there,” Pepper said, “and I remembered what you said about getting the Bible, so I picked it up. The paper was inside. This is a photocopy, of course.”

I forced myself upright in the bed. “Let me see.”

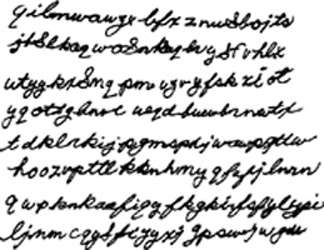

She held it in front of me and I looked at the jumble of letters:

“Anybody figured it out yet?” I asked.

Shelby cleared his throat. “We’re working on it.”

“Jefferson’s cipher machine?” I asked.

“Jefferson, yes,” Shelby confirmed. “Cipher machine, no.”

“But it’s the same principle,” Esme said. “We think it has to be what they call a Vigenère cipher. It was invented four hundred years ago by a Frenchman named Blaise de Vigenère. It depends on a special word as the key to enciphering the message. Once the message is enciphered, the security is all but unbreakable.”

“Or used to be,” Sam said. “Nowadays, computers can break them. That’s our next step.”

“It will only work if you have a long enough text,” Pepper said.

Esme put a hand on my shoulder.

“Poor Alan, we’re wearing him out. Don’t worry, we’ll figure it out. You just get some sleep. All you need to know is we’ve found the documents and we know now who the old man was, and that’s enough.”

I slept. I dreamed. It was summer and the sweet smell of growing sugarcane cloyed the air. There was a thin thread of harpsichord music coming from the big house and as the old man toiled in the garden, the music brought back sharp images that startled and discomfited him. Like a kaleidoscope, they tumbled before him, until he fell over onto the ground, his head against the hard gumbo mud. Who were these girls, in their ball gowns? These men in carriages? What house was that, and in what distant place? Were these the shadows of his past or were they merely the intimation of approaching death?

He scrambled up onto his knees and shook his head to clear it.

Block away the hallucinations. Focus on what has to be done. Gather in the corn. The cabbages. The artichokes …

The next time I woke up the room was dark and only Pepper was there.

“They’re gone,” she said, “but it’s nice to have friends.”

“Yeah.” I sighed. “The last thing I remember is trying to get the gun.”

“The room blew up,” Pepper said. “The door protected you, but Rosemary was still inside.”

“Her father?”

“He didn’t make it. I was out of the line of the blast. I managed to get you out. There isn’t anything standing.”

I shut my eyes. The memory was too strong to confront and I tried to block it out by focusing on something else. “How did you know where to find me?” I asked.

“It’s complicated,” she said vaguely. “We’ll talk when you’re better.”

My head swam. I couldn’t keep my train of thought. Then the strange message written by Meriwether Lewis crystallized in my mind and I tried to hold the focus.

“… about the cipher …” I began.

Pepper smiled. “A man in the math department’s working on it.”

“Try artichokes,” I said.

“What?”

“The key word. Try artichokes.”

She shrugged. “Are you serious, or should I call the doctor?”

“Do you remember all the speculation about where the old man buried the box?”

“We thought at first he put it in his garden,” she said.

“Because of his ramblings while he was dying,” I told her.

“Right. He was talking about vegetables.”

“Not just vegetables,” I said. “One kind of vegetable.”

“What?”

“Remember?” I prodded.

“Artichokes.”

She came back hours later.

“It worked,” she said, nodding. “Artichokes was the key.”

I lay back against the pillow. “So simple.”

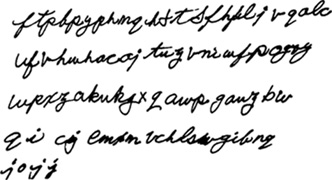

She reached into her handbag, removed a sheet of paper, and handed it to me. I took it in one trembling hand and read the typed message:

Presdt. Thos. Jefferson

Dear Sir

I could not bring the documents with me for fear of Genl Ws spies. A full account of his acts I have buryd at the base of lrge oak tree 50 paces SE of blacksmiths cabn at Ft Pickrng. For sake of the Repub send Genl Clark for these papers as I may be done to death when you get this.

Wrttn on the 29th inst by Yr dvtd svt and friend, M. Lewis

“Of course,” Pepper said, “I’ve added punctuation, but I’ve left his abbreviations the way he wrote them.”

I reread the message and then let it fall onto my chest.

“So it was Wilkinson after all,” I said.

“He thought so,” Pepper said. “Shelby said Wilkinson was into all sorts of corrupt land deals when he was governor of Upper Louisiana, before Lewis came. He thinks Lewis may have found out some incriminating details. Maybe even had evidence of Wilkinson’s treason, because there was a strong Spanish colony in St. Louis.”

“And the map was Fort Pickering,” I said.

“Right. And now it’s part of Memphis.”

“You mean …”

“I called an archaeologist up there,” she said. “The old fort was pretty well demolished by Civil War breastworks and a moat a hundred and thirty-odd years ago. In fact, nobody’s even sure just where it was.”

“He encoded the message while he was at Pickering,” I said. “Right after he buried the evidence. Something happened to make him fear for his life.”

“Major Neelly appeared from nowhere and offered his services,” Pepper said simply. “That’s the only thing that makes sense.”

Neelly, Russell, Grinder, Pernier ….

The names swirled in my mind once more and whatever they’d given me to make me sleep was pressing my eyes shut. I felt her hand in mine and squeezed it to assure myself she was still there, but there was no holding off sleep. And as I slept I dreamed:

As the sun went down the man in the duster leaned back against the outer wall of the cabin, inhaled the smell of the wood fire, and took a sip of the whiskey the woman had provided. It was vile stuff, but it was what he was used to, and he needed it to keep his head level.

He was waiting for one man. He wasn’t sure who it would be, but he knew that man would come.

Last night, at the camp near the mudhole, he hadn’t slept: There was something about the Indian agent, Neelly, a restlessness. He’d fiddled with his gear, given the servants sidelong glances.

Are you the one? Well, you won’t get me here.

Then, in the early hours of morning, the camp had been awakened by a halloa. The major was claiming two of the horses were loose, and in the morning he’d insisted on staying behind to find them. But the horses had been securely hobbled. What was the major trying to do? Was it part of a plan to meet his accomplices?

There was nothing to do but feign innocence, as if he suspected nothing. But the business was coming to a head. And he’d learned long ago, as a soldier, and then again with the Indians, that the only way to deal with a danger was to face it.

If only the danger had a face.

What if it was his man Pernier?

He’d pulled Pernier off the St. Louis docks, taken him into his home, and paid the doctor with his own money when the man was sick. Pernier professed to be grateful. But there was much that was mysterious about John Pernier, things the man said that did not ring true, as if he reinvented his story with every passing day. Worse, now he owed Pernier back wages, because he’d had to scrape together all he could put his hands on to make the Washington trip. Pernier had seemed satisfied. But lately he’d appeared restless, almost shifty. What if …?

Then there was the woman. She said she was alone here, with her children, but how could he be certain? What if the general had sent a rider, paid off her husband? What if the husband was waiting in the woods, had his rifle leveled at this very moment?

The man wiped his forehead with an arm. The fever was coming back. He was getting the sweats. God, how could he fight this battle if he was going to be sick?

A sound on the trail caught his attention and he put his hand on one of the pistols in his belt.

Who …?

The bushes parted and a pair of riders emerged. Which way had they come from? Why hadn’t he noticed?

He rose, swaying, and drew both pieces.

The men took one look at him, turned their mounts, and spurred away.

“Is something wrong?” the woman called from behind him.

“No, madam.” He stuck the pistols back into his belt and sat down again. “There’s nothing wrong.”

“Do you want some supper?”

He didn’t answer and a few minutes later she handed him a plate with some corn gruel. He looked down at it.

What if she’s poisoned it? It would be so easy to put something in it.

Don’t be insane: You drank her spirits.

Maybe you were lucky. Don’t take another chance.

He set the gruel aside.

“Someone else is coming,” she said from behind him.

He looked up, reached for his pistols, and kept his hands on their butts as the sound of riders echoed across the clearing.

It was Pernier and Neelly’s servant.

He stood up unsteadily and watched the men plod toward the house.

“Are you alone?” he hailed.

“Yes, sir,” Pernier replied. “The major hasn’t come.”

“Do you have powder?” he asked, thinking it would be as well to be prepared.

“Yes, sir.” Pernier looked perplexed.

The woman came forward and directed the young Negro boy to take the horses.

“They can stay in the stable,” she said, and the traveler nodded. Safer for him to be alone. People had been shot in their beds.

Then he had second thoughts: If the woman was a part of it, she could be trying to isolate him.

But he was tired. His eyes were closing and he was already trembling from the fever. What could he do?

He followed her into the single room of the cabin.

“I’ll fix your bed,” she offered.

“Madam, I’m used to the floor,” he said, nodding at the split-board flooring. “Have my man bring my bearskin.”

Pernier handed in the skin.

“Governor Lewis, do you want me to stay with you?”

“No, sir, I do not.”

“Governor—”

“Good night to you.”

He closed the door, spread his bearskin, put his pistols on the floor beside him, and lay down.

God, how he craved sleep, and yet his mind would not be still. Instead, the speech he had so carefully prepared for the Secretary of War raced through his thoughts. He got up. Maybe if he paced a bit, practiced the speech, it would fatigue him enough to make him sleep.

He rose and began to articulate the words he’d prepared.

“Mr. Secretary, if my ruination were able to save the nation I would gladly give all that I own. But you must know that there is a grave danger…”

“Sir, are you well?”

It was the woman’s voice, calling from outside the door. With a start he realized he’d been enunciating the speech aloud.

“I am well, madam.”

He lay down again and this time, when the door opened slowly in the early hours of the chill morning, he was asleep.

The man Pernier awoke with a start: A gun had been fired outside. As he rose from his blanket another shot exploded nearby. He threw on his trousers, grabbed his pistol, and ran out into the chill mist. The woman was screaming now and there was a sound of struggle near the cabin where the governor was staying. When Pernier reached the cabin the door burst open and two men fell out onto the ground, their bodies locked together. One rose, a dagger in his hand, but Pernier knocked it away. The man swore, pulled a small pistol from his waistband, but Pernier fired at the man’s head. The man coughed and fell onto the ground, writhing, his face a mass of blood and torn flesh.

Pernier looked down at the man’s victim. Even in the grayness he could make out the face of Governor Lewis.

He leaned down, put his ear over the governor’s mouth, and felt Lewis’s breath. Ragged but present. The governor was still alive. But he was badly wounded, his head a mass of blood.

The woman came up then, holding a candle.

“In the name of God, what is it?” she cried, holding her shawl closed with a trembling hand.

Pernier seized the candle and held it near the dead man’s face.

A stranger.

“Do you know him?” he demanded.

“No.”

“Madam, do not lie.”

“I swear by the Almighty.”

“Then he was sent here.”

“By whom?”

“Never mind. Madam, this is what we must do: We must undress this man and put his clothes on the man who still lives.”

“Are you insane?”

But Pernier was already dragging the dead man around the end of the cabin.

A rush of footsteps announced Neelly’s Negro servant, but Pernier blocked the man with his body.

“There has been a tragedy. You must ride back along the trail and find Major Neelly.”

“A tragedy? But what?”

Pernier pointed at the fallen Lewis. “The governor is dead.”

“Good Lord.”

“Go!” Pernier commanded, and only when the man had saddled and ridden away did he turn back to the trembling Mrs. Grinder.

“Now listen to me. What I am telling you must be between us and your husband. The life of a great man depends on it.”

The Grinder children and the Negro slave boy and girl were staring from the door of the other cabin now, and Pernier lifted Lewis under the shoulders and carried him to a spot away from their gaze.

“Help me change their clothes.”

“But this makes no sense. The law—”

“I will represent the law. I promise you, madam, that I answer to people who can do you infinite good or harm. The man on the ground before you is the governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory. I was sent to protect him and I have failed. But I swear to God I shall not fail again. Where is your man?”

“On Swan River, twenty miles off. He sleeps there during harvest.”

“Send the black boy for him. In the meantime, you and the girl must take this man to a safe place in the woods. When your husband comes, tell him what happened. Tell him that the government will pay a reward for his attentions. But this man must not die, nor must it be known that he has survived, else other assassins will be sent after him—and you.”

“Before God, sir—”

“Madam, do as I say.”

They unclothed both men and then dressed each in the other’s garments. When they were done, Pernier asked for a shovel and, in a clearing a hundred yards from the cabins, dug a shallow grave.

It all hinged on Neelly, of course. The man was a drunkard and a coward. He had clearly dawdled in recovering the lost horses because he didn’t want to be here when the deed was done.

It was on his cowardice that Pernier placed all his hopes.

Now all Pernier could do was wait.

Neelly came just after dawn, unsteady in his saddle, leading the two pack animals, with his servant chattering away excitedly as they entered the clearing. Pernier got up and went to meet them.

“Pernier, what the devil’s happened?” Neelly asked, slurring his words slightly.

Pernier assumed his servant’s attitude.

“A terrible tragedy, Major, sir. The governor is dead.”

“Dead? By God, man, how did it happen?”

There was a bit too much bluster in Neelly’s tone, but Pernier could tell that it masked fear, and that was good.

“From all I can tell, sir, he destroyed himself.

“What?” The idea seemed to hit Neelly like a cannonball. “You mean…?”

“I heard a terrible row, and shots, and we found the governor dying on the ground. His pistols had been discharged. He begged us to put an end to his pain.”

“And he did this to himself?”

“It would appear so.”

Neelly swayed and for an instant Pernier thought he was about to topple from the saddle.

“Did the woman see this?”

“Yes, sir. She says that he was talking to himself, that he all but admitted it after the shots, as he lay wounded.”

“Where is she now?”

“Gone for her husband.”

Neelly looked over at his own servant, but the man only shrugged.

“Where is the body?” the major asked.

“Buried,” Pernier declared. “It seemed indecent to leave him exposed. I can show you the grave.”

He walked ahead of Neelly’s horse to the place where he’d dug the shallow grave and, reaching down, began to scrape away the dirt and stones with his hands.

Dear God, let him be too drunk to care. Let him be afraid. Let him be anything but a conscientious man …

His hands came to the body’s clothing and he cleared away enough dirt to expose the leather coat the governor had been wearing, but which was now on the body of the man who had tried to kill him.

“Shall I go further?” he asked, and began to clear away the neck area, and then the head. The face, with its awful, disfiguring wound, had just been uncovered when Neelly cried out from his horse, “Stop. Enough. Cover him back up.”

They returned to the cabins and Neelly dismounted, wavering in the morning sun.

“I’ll have to make a report. I am the representative of the government here. Suicide, eh?”

Pernier went into the cookhouse, now deserted by the Grinder children, who had been herded away by their mother, and found a jug. He brought it out to the major.

“Something to drink, sir?”

Neelly grunted and yanked it out of the other man’s hand.

It was easy to tell what he was thinking: The governor had been acting in a deranged fashion, had even talked about killing himself, so suicide would be a believable verdict. If the real murderer had gotten away, so much the better. There would be no outcry, no demand to punish the guilty. Yes, this would work out very well, and Neelly would collect his fee.

By midmorning Neelly was gone, on the way to Nashville with the news, and the woman had returned with her husband, a rough-looking man with a scowl.

“Keep the governor out of sight,” Pernier ordered. “You will be paid. When he has recovered, an escort will be sent for him.”

“And his things?” the man asked.

“The major took them on the packhorses. His personal belongings are to stay with him. I know of nothing of any importance.”

“There’s some land I’m looking to buy,” the man Grinder said.

“Handle this and you’ll buy it,” Pernier promised. “But mind you this: When the inquest is held, you are to swear to the story I told you. The man in the grave is Governor Lewis. Show him to the justice of the peace, and then rebury him. But there must be no hint that Lewis lives.”

Grinder, who did not look like a man who would be bothered by false swearing, nodded.

“I’ll take him to the Chickasaws when he gets better. He was awake when I stopped to look at him.”

“But saying crazy things,” the woman said. “His head wound is terrible. I’m afraid it may have knocked all the sense out of him.”

“Then take care of him until he regains it,” Pernier said. “But I have a journey to complete.”

And more mountains and forests and rivers to traverse, until he came to the hills of Virginia and the great white hall of Monticello and the man who waited inside for his report. He wondered what that man would say.