The Boxer rising was not a formally planned military campaign in the traditional sense, but rather a spontaneous rising by a section of Chinese society against the domination of their country by the foreign powers. As such there was little in the way of identifiable planning. Even the actions of the foreign powers were largely reactive and initially focused on little more than the relief of the settlements at Tientsin and Peking. The appeal of the Boxers to the average Chinese peasant in the late 1890s was their declared goal of destroying the foreign presence in their country, preserving the religions and culture of China, restoring the geographical and political integrity of the country from foreign incursions, and to a lesser extent their anti-Manchu stance, who were considered by some to be non-Chinese. By the summer of 1900, many in the Chinese court and government including the Dowager Empress had come to see the Boxers as the instrument for ridding the country of foreigners and foreign domination. Yet only a few months earlier, many Chinese leaders had urged that the Boxers be suppressed for fears of upsetting other nations. This dichotomy reveals the problems facing the Chinese authorities in 1900: on the one hand they wished for nothing else but to banish foreigners from the country, while at the same time not wanting to offend the various powers who had interests in the country. This further explains the considerable restraint displayed by the Chinese in their prosecution of the siege of the Peking Legations, even to the extent of supplying fresh fruit to the beleaguered defenders on several occasions. With little effort the Chinese could easily have overwhelmed the defenders at any time if they had so wished. The fact that they did not suggests that the moderates in the court and the commander of the Imperial troops, Jung Lu, were not aggressively anti-foreign but, in a court dominated by the extremists, were forced to act as though they were.

Admiral Seymour and staff photographed on board HMS Centurion. Left to right: Flag Lieutenant F.A. Powlett, Flag Captain J.R. Jellicoe, who was to achieve fame at the Battle of Jutland in 1916, Admiral Sir E.H. Seymour and his secretary, Fleet-Paymaster, F.C. Alton. Powlett, Alton and Jellicoe accompanied Seymour on his failed mission, and Jellicoe was wounded at Peitang during the retreat. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

While the western powers were shocked and outraged at the various atrocities committed against their citizens between 1898 and 1900, few of the nations other than Germany urged armed intervention. However, once the crisis came to a head and the foreign representatives were caught in Peking two aims quickly emerged: to rescue the foreign community in the capital and punish the Chinese for this breach of international law. However, the response of the allied powers enflamed the situation, leaving the Chinese with little option but to declare war.

The siege of the Legations can be seen as falling into two stages. During the first, which lasted only ten days or so, the Boxers were the main enemies, while the Chinese government and the Imperial army kept somewhat neutral and in some areas the army was even used against the Boxers. In the second stage of approximately eight weeks’ duration, the government, court, and army became the enemy and the Boxers almost became ineffective bystanders. The defining moment in the crisis and the one which brought about this significant change was the storming of the forts at Taku on 17 June 1900 which was viewed by the Chinese as an act of war. The government responded by stating that ‘our country is therefore at war with yours. You must accordingly quit our capital within twenty-four hours accompanied by all your nationals.’ As one writer described the consequence of this: ‘Exit Boxers – enter the regular Chinese army.’ Thereafter, the foreigners, particularly the various relief columns, faced the full force of China’s army.

The besieged hung on, acutely aware of what atrocities had been committed against their countrymen. They expected to be massacred at any moment and while their hopes were kept up by rumours of the various relief forces, few thought that they would be saved in time. Under the leadership of Sir Claude MacDonald, the British Minister in Peking, the plan of the besieged was simple – to hang on as long as possible until help arrived. He therefore established committees to organise among other things food supply, medical needs, and the construction of fortifications.

For the two relief columns the task was quite simply to get through to Peking, relieve the Legations and quell any further Boxer insurrections. The premature news that all foreigners in Peking had been massacred provided the pretext for such a move. Seymour’s expedition was a response to the fear that the foreigners in Peking would be isolated and attacked. The governments of the various nations gave the go-ahead to their admirals to do whatever they could to save the foreign nationals. The failure of the first relief expedition was due to Admiral Seymour acting independently of his fellow admirals – an impulsive act in response to Sir Claude MacDonald’s urgent call for help. By contrast, the second relief force was successful largely because it was a unified multinational force which brought the full weight of available military resources to bear against the Chinese.

Once Peking had been relieved, the plans of the allies changed from one of saving the foreigners in the capital to one of punishing the perpetrators and destroying the Boxer movement while at the same time using the crisis to further each nation’s economic and political designs on China.

The first two weeks of June 1900 witnessed a series of events in Peking which gradually deteriorated particularly after the allies had stormed the Taku Forts on the 17th. Prior to that it had appeared as though the Chinese were toying with the foreigners in Peking and making veiled threats, but they had not taken any action against the diplomats and their families. Boxers had been seen in and around the foreign enclave and anti-foreign placards had appeared, but on the 9th they struck their first blow when a crowd of rioters burnt down the grandstand of the Peking Race Course situated just beyond the southern gates of the city, killing in the process a number of Chinese Christians who had been forced into the building. The foreign community had created its own culture within Peking and racing was a particular favourite with the diplomatic corps. To the Chinese, the Race Course and the popular race days were seen as symbolic of everything that was bad about foreign culture.

The most significant response and the one which escalated the situation was Sir Claude MacDonald’s telegram to Sir Edward Seymour at Taku informing him that ‘the situation in Peking is hourly become more serious’, and requesting that a relief force be dispatched to the capital. While the diplomatic corps was critical of MacDonald’s over-reaction, it nonetheless made preparations to accommodate Chinese converts and other refugees in the Legation Quarter while at the same time handing over responsibility of missionary properties to the Chinese government on the condition that it would be held directly responsible for any damage inflicted by the Boxers. Rumours abounded that part of the railway line between Peking and Tientsin had been destroyed by Boxers who were now pouring into Chihli Province from Shantung Province where the first outrages against foreigners had occurred, and much of the countryside around Tientsin and Peking was under their control. Chinese Imperial troops who had been sent to quell them were either withdrawing or actively collaborating with the rebels, whose widespread appeal was their desire to destroy all semblance of foreign presence in China. It was the misfortune of any foreigners to be left out in the countryside and a number of missionaries and converts were murdered at Tungchow, west of the capital.

Even though the foreigners in Peking itself were still at peace with their Chinese neighbours in the middle of June, MacDonald’s plea for help caused the allied commanders at Taku some concern and their subsequent actions led to an escalation of the situation. The allied fleet of 15 advance vessels had taken up anchorage off Taku Bar in the Gulf of Pechihli by late May as a show of strength to warn the Chinese government that any further outrages committed against their nationals would be tantamount to an act of war. A contingent of foreign troops had been landed on 31 May and entrained for Peking at the request of the diplomats as further protection. A few days later, additional troops had been landed and sent to Tientsin, 30 miles from Taku, in the event that the situation deteriorated. The various allied admirals had agreed that if Peking was cut off, they would dispatch a relief force, but it was the arrival of MacDonald’s telegram that brought about the next move.

Admiral Sir Edward Seymour, sensing the urgency of his countryman’s request, decided to act and ordered his force ashore with the request that contingents from the other nations follow. ‘I am landing at once with all available men,’ he stated. It was a hasty move with barely any thought of a plan other than to move on Peking. While Seymour was a good sailor, he lacked experience in land warfare and he was not the ideal person to lead the expedition but there was probably no one else. The allied force, consisting of British, German, French, Russian, American, Japanese, Italian and Austrian sailors and marines, assembled at Tientsin on 10 June. Shortly after, the combined force of just over 2,100 men set off in five trains in the hope of reaching the capital before nightfall. Their main armament was seven field guns and ten machine guns. Between them lay 80 miles of open ground traversed by the single rail track and exposed to Boxers and a large force of foreign-trained Imperial troops under General Nieh Shih-ch’eng who were now in full support of the rebels’ cause. Ironically this same Chinese army had only a week earlier won a successful action against the very Boxers they were now united with.

German sailors and marines attacking Chinese troops on the railway track during the Seymour Relief Expedition. Germany dispatched 1,126 men of the 3rd Seebataillon along with other units from Tsingtao to participate in the campaign. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

The journey went well for the first few miles and there was little evidence of the Boxers beyond some burnt tracks as Captain-Lieutenant Paul Schlieper of the German Imperial Navy noted in his diary: ‘The rebels had set fire to the wooden sleepers after drenching them with petroleum; many were charred, and several still smoking. The discovery warned us to be on our guard, but no further hindrance was met with.’ Schlieper reported passing the camps of the Chinese regular troops (at Yangtsun) who barely stirred as the trains passed: ‘It did not look as if the camps feared the terrible Boxers much, and experience was to show us later pretty clearly that the regulars had secretly made common cause with them.’ A broken bridge was repaired and following a bivouac, the force continued on towards Peking on the 11th albeit slowly. The trains were soon halted at Langfang halfway to the capital where the lines had been torn up. Lacking further equipment to repair the track, requests were sent back to Tientsin for further supplies.

The Hsiku Arsenal in a photograph which was widely published during 1900. After crossing the river in small junks, British and German sailors and marines from Seymour’s force captured the arsenal, which was garrisoned by Imperial troops, at 10.00am on 23 June 1900 after heavy fighting. The expedition was forced to wait here until a relief force from Tientsin arrived. The arsenal was destroyed by this force on its retreat back to Tientsin. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Bivouac outside the Hsiku Arsenal – British troops from Tientsin for the relief of Seymour’s Column, in a photograph published in September 1900 in Navy and Army Illustrated. In the photograph can be seen Indian troops and members of the Weihaiwei (1st Chinese) Regiment wearing straw-brimmed hats. In the background, Russian troops can be seen marching. (Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Reports were now reaching Seymour that any retreat back to Tientsin would be difficult as Boxers and Imperial troops had now occupied the line between him and the city. At the same time a messenger from the American Legation in Peking reached Langfang reporting that there was a great sense of expectation in the capital of the arrival of the relief force. The tracks at Langfang would take about three days to repair. A small defensive position was established there called Fort Gefion after the German ship from which the marines came, and on the 14th, it was attacked by several hundred Boxers. On the following day, Seymour dispatched a train to Tientsin but it was forced to return as the tracks had been destroyed.

Unable to advance northwards in safety or retreat south, Seymour decided upon a river route to Peking which would require retreating to Yangtsun and then striking north up the Peiho River. While a German force was left to guard Langfang, the rest of the allied contingent retreated to Yangtsun, where four junks were captured. On 18 June, the Germans at Langfang were attacked by 4,000 Boxers and Chinese regulars but these were repulsed. Langfang was evacuated and the Germans retreated on their train to Yangtsun. Seymour’s worst fears were confirmed when the German commander informed him that Chinese Imperial troops had now taken the field against the allies. As soon as the force had taken to the river the empty trains were plundered by the Boxers. Even progress along the river was hampered due to low water levels and it was decided to march along the river banks, leaving the sick and wounded in the junks sailing close alongside. A council of the various commanding officers decided that any further attempt towards Peking was out of the question and that an immediate retreat to Tientsin should begin.

Captain Schlieper described their situation: ‘Our advance now proceeded very slowly. The enemy showed wonderful tenacity and had to be pushed back step by step. When one village was cleared a still hotter fire was sure to be opened on us from the next. It was a tough bit of work.’ Eventually, on 22 June, a large building which turned out to be the Chinese Imperial Arsenal at Hsiku was attacked and captured. Although only about 6 miles from the foreign settlement at Tientsin, the messengers dispatched by Seymour were all captured. There was nothing else to do but sit and wait for relief to come, which it did on 25 June when a force of 1,000 Russians, Germans and Japanese were able to fight their way through and escort the force back to Tientsin with losses amounting to 62 killed and 232 wounded. As one writer explained, the disastrous relief attempt had not been wholly Seymour’s fault but his main mistake was in moving a large, ill-equipped force inland without guarding his line of supply. The fact that his force was attacked sharply on several occasions after 18 June was not of his doing but a result of events which had taken place on the coast at Taku.

Following Seymour’s departure for Peking on 9 June, the remaining admirals had decided not to take any additional action for the time being, but as reports came in of increased Boxer activity over the next two weeks, particularly the occupation of the native city at Tientsin, which threatened the foreign settlement in that city, they began to rethink their strategy. There was also a rumour that a major uprising was set to begin on the 19th and nothing had been heard from Seymour. All this combined to convince the admirals that they should act sooner rather than later to prevent the Boxers overwhelming the foreign section of Tientsin and taking control of this important centre which the allies needed as a base of operations to relieve Peking.

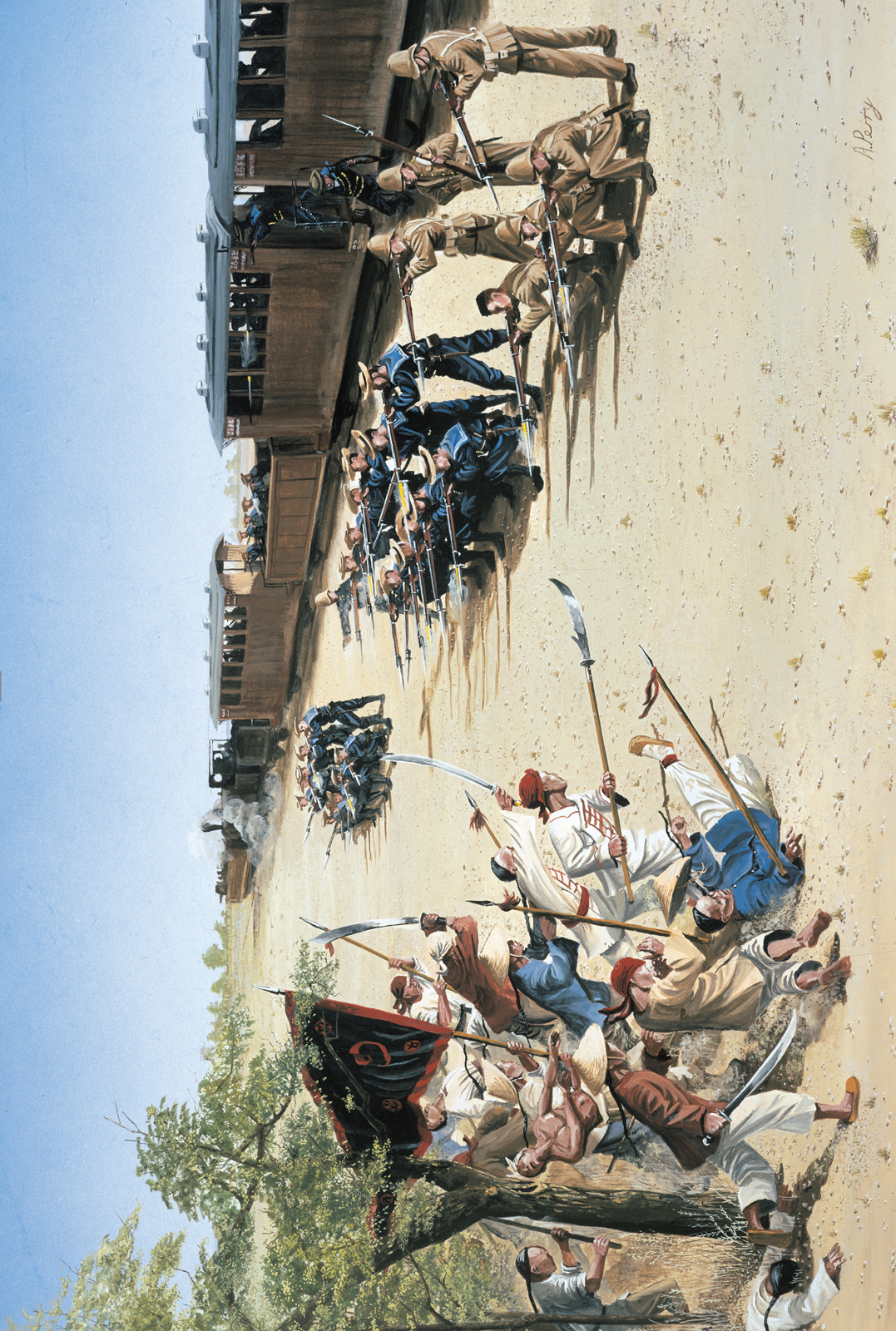

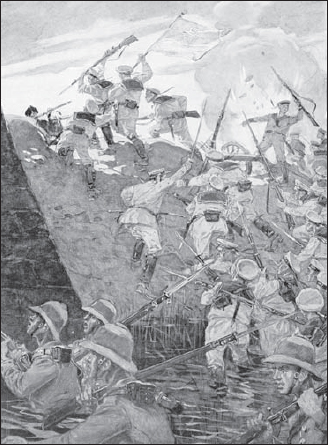

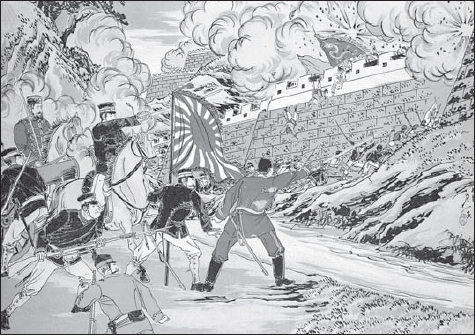

BOXER ATTACK ON ADMIRAL SEYMOUR’S RELIEF EXPEDITION AT LOFA, 11 JUNE 1900

That afternoon the lead train was attacked by the Chinese. ‘Not more than a couple of hundred, armed with swords, spears, gingals (blunderbusses) and rifles, many of them being quite boys … there was no sign of fear or hesitation, and these were not fanatical braves, or the trained soldiers of the Empress, but the quiet peace-loving peasantry – the countryside in arms against the foreigner’. C. Bigham. (Alan & Michael Perry)

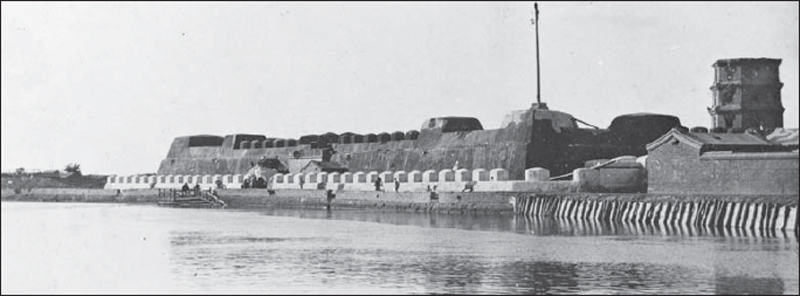

The Taku Forts photographed by Nathan J. Sargent, a clerk in the office of the American Trading Company who was a talented amateur photographer. His work frequently appeared in accounts published after the Peking siege. Sargent was in Tientsin during the siege of that place and was a member of the volunteers. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

On 15 June a military council was convened on board the Russian flagship Rossia, one of the allied ships which were lying at anchor 10 miles offshore. Those present included Commander C.G.F.M. Craddock, officer commanding British naval forces in Seymour’s absence, Vice-Admiral Bendemann, commander of the German Squadron in the Far East, and Rear-Admiral Courrejolles in command of the French Division in Chinese Waters. It met to consider the latest intelligence – that 2,000 rebels might cut the line to Tientsin, were poised to take over the Taku Forts from the Imperial troops, and had begun mining the Peiho River. On the previous day, reports had reached the coast that Baron von Ketteler, the German minister, had been killed in Peking. He was the second diplomat to die, the Japanese chancellor, Akira Sugiyama, having also died under suspicious circumstances. The information came not by telegraph, which had been cut, but by word of mouth and its reliability was therefore subject to question. Some substantiation came in the form of a press release circulated by the respected Laffan’s News Agency through a telegraphic report. The London Times picked up the report and published, it adding further credence to the rumour. Surprisingly, the press release Laffan’s issued on 16 June predated von Ketteler’s death by four days, providing one of the many enigmas of the rebellion.

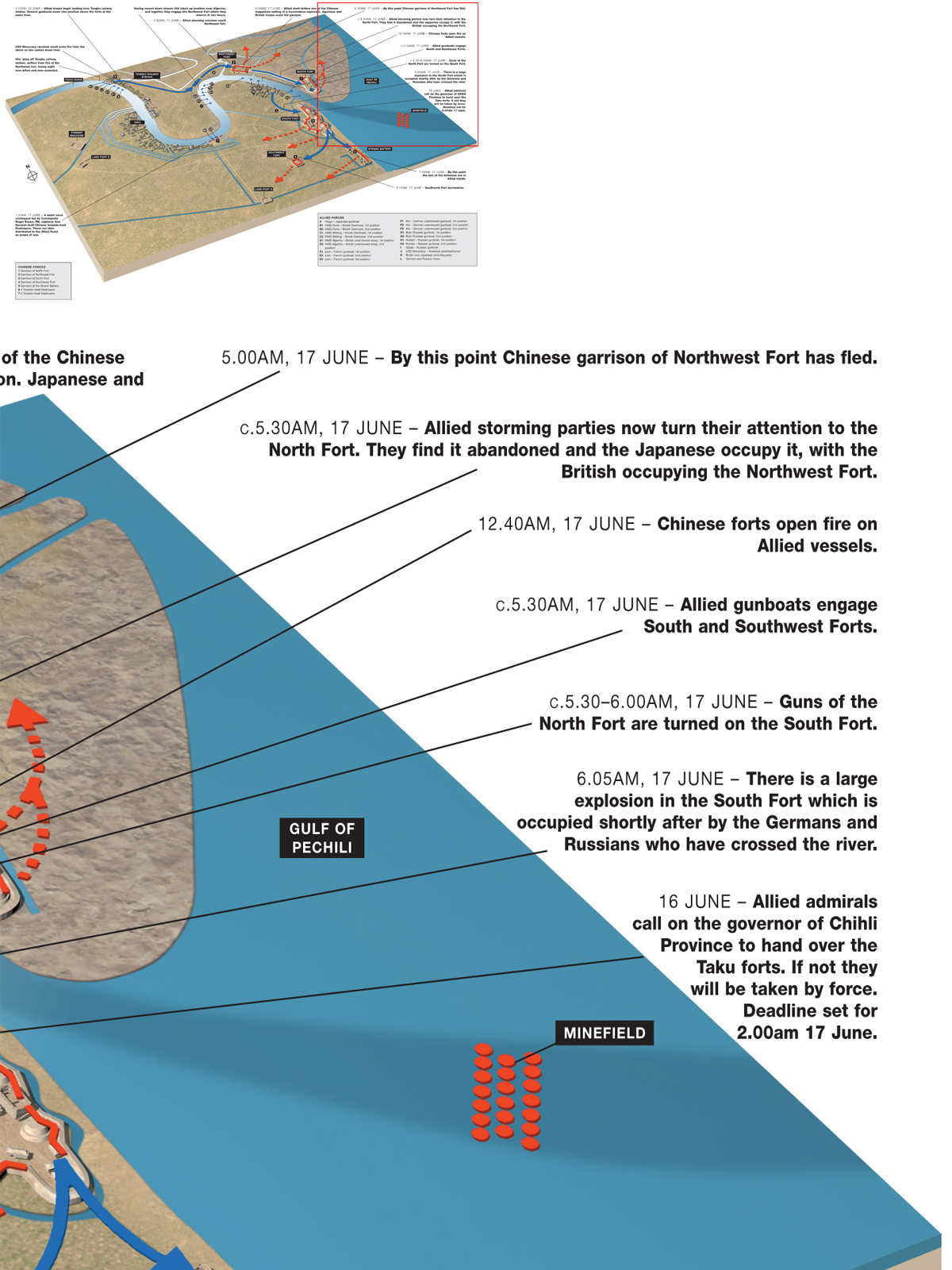

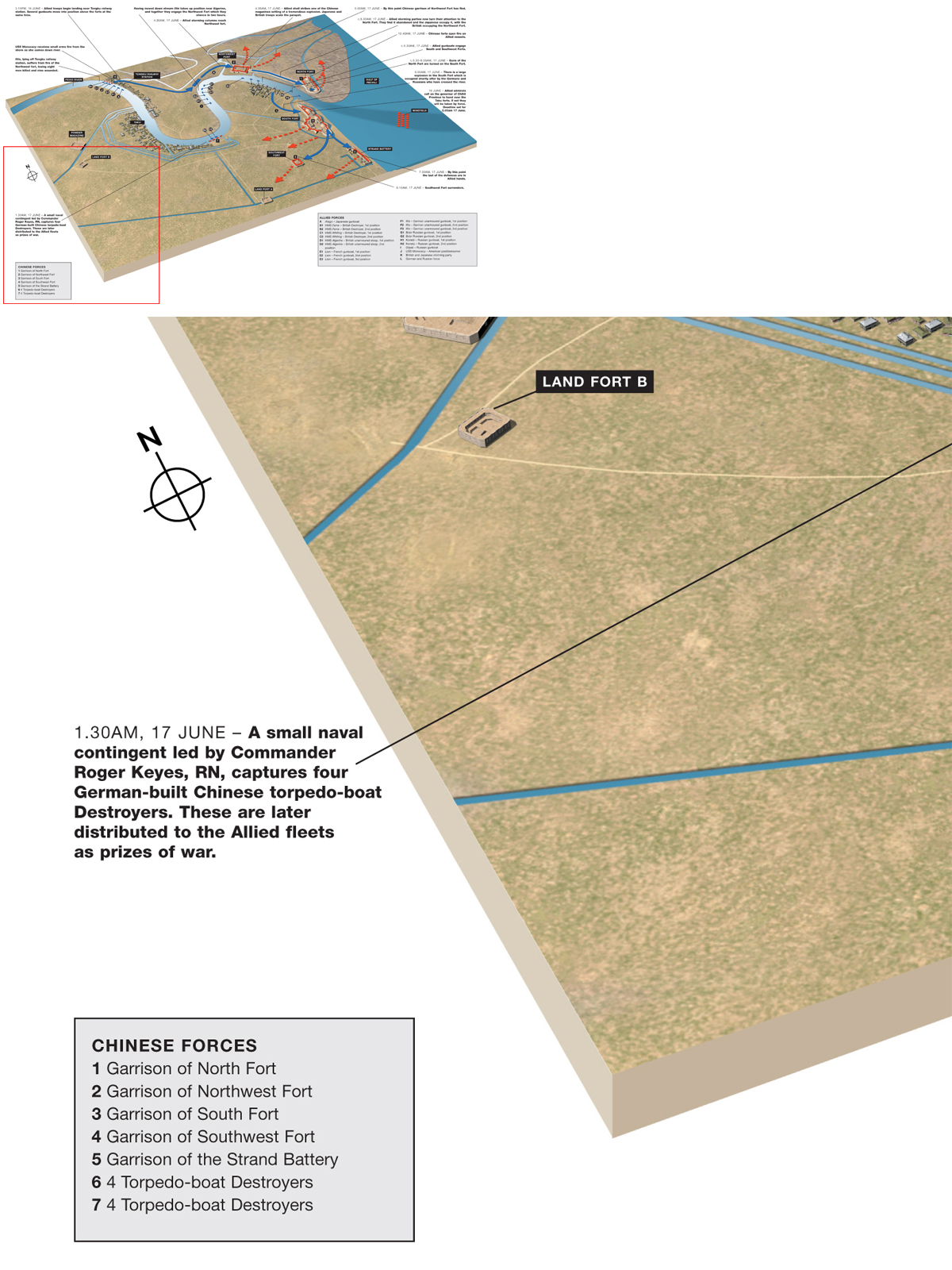

The situation came to a head when Chinese Imperial troops were seen occupying the railway and laying mines in the river. At another council meeting on 16 June, the admirals resolved to take immediate offensive action by capturing the Taku Forts. These were five forts on the Gulf of Pechihli located at the mouth of the Peiho River; two were situated on the north bank – No. 1 known as the North Fort, and No. 4 known as the Northwest (or inner) Fort. The remaining three were on the southern bank – Nos. 2, 3 and 5 known collectively as the South Forts. All were garrisoned by troops of the Imperial army. The forts were well known to the allies, having been stormed forty years earlier, although the defences had been improved considerably since then. Significantly the large guns of the forts pointed out to sea, making them useless against any attack coming from inland.

S.M. Kanonenboot Iltis bombarding the Taku Forts in an exciting but purely imaginary scene painted by the distinguished German naval artist Willy Stower. The Iltis lying off Tongku railway station suffered severely from the fire of the Northwest Fort at Taku but shortly after moved down river and took up a position along with HMS Algerine where they bombarded the fort for two hours. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

The first to scale the rampart of the Taku Forts: assault delivered by German and Austrian sailors at 6.00am on 17 June, 1900, as sketched by Schönberg and published on 8 December. The caption stated that the approach to the forts was defended by hidden mines; while in front of the entrance to the North Fort was a brick wall which was scaled as the gate could not be forced. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

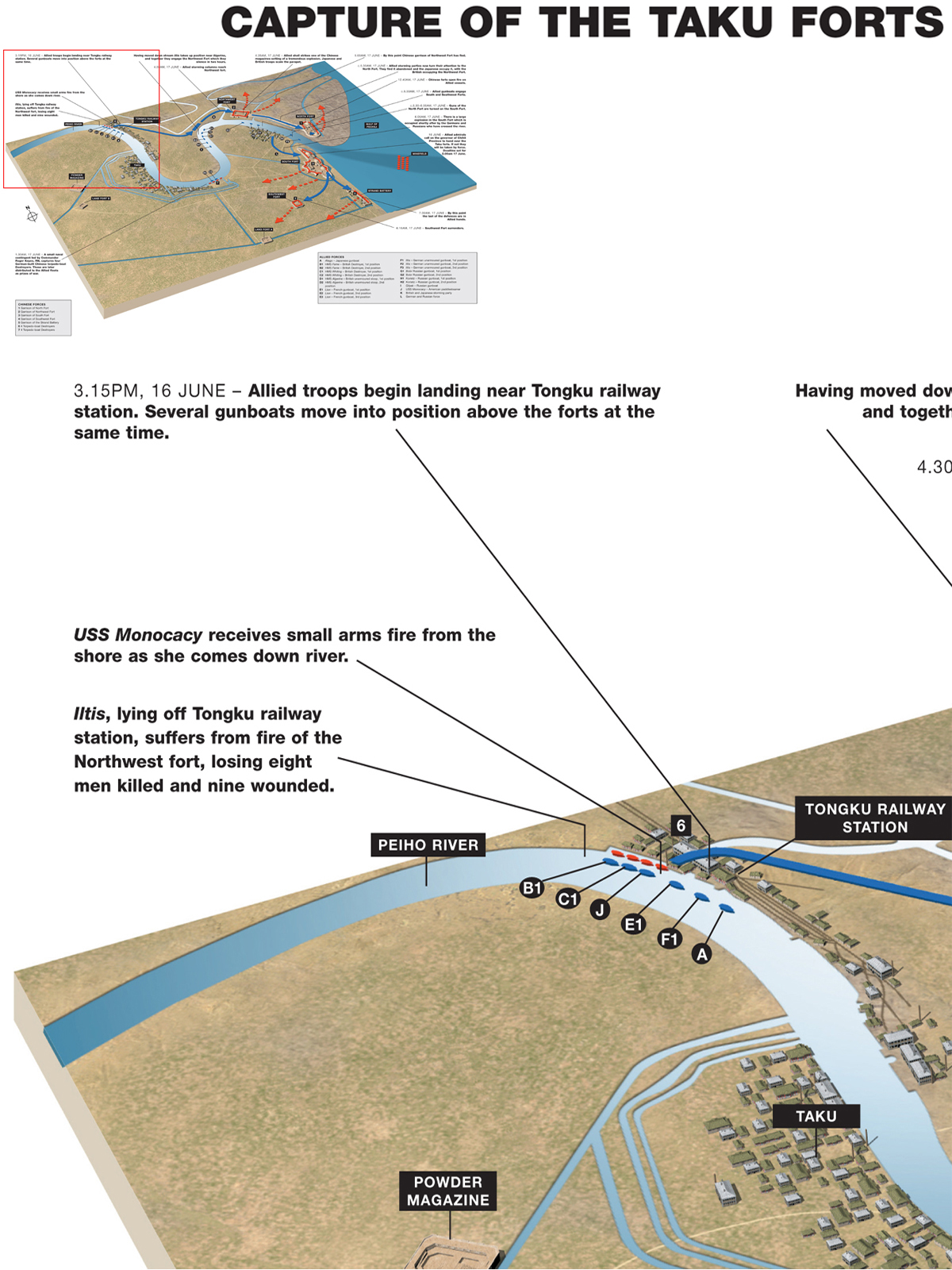

Following the meeting, the admirals gave the Chinese an option to surrender the forts peacefully by calling on the Governor of Chihli Province to hand them over but stating that if he declined, the forts would be taken by force. While the deadline was set for 2.00am on 17 June, the allies anticipating a rejection had begun to land troops near Tongku Railway Station further up the river. At 3.15pm on the afternoon of 16 June, 180 Russians were landed and 45 minutes later, 250 British and 130 German soldiers and marines followed. Three hundred Japanese troops were also landed to act as a reserve and were joined by some small contingents from Austria and Italy. Several gunboats had also moved into place. By early evening the situation had become critical as there was no sign that the Chinese intended to surrender the forts.

The entrance to the Peiho River was blocked by a sand bar which meant that only smaller ships could enter. Ten allied ships took up position inside the bar while the remainder of the fleet lay out in the Gulf. What the allies had demanded was viewed as an act of war by the Chinese, and observing the allied ships moving up the Peiho River, the forts opened fire at 12.40am on Sunday 17 June. They targeted the old iron Japanese gunboat Atago, the modern British destroyers HMS Fame and Whiting accompanying the unarmoured sloop HMS Algerine, the old French gunboat Lion, the USS Monocacy, an old American wooden paddle-steamer built in 1863, the German unarmoured vessel Iltis, and the Russian ships Bobr – an old steel gunboat armed with muzzle-loading weapons – the Korietz, which was similar, and the Gilyak, a modern gunboat. A number of civilian vessels were tied up along the wharves at Taku and an officer on board one ship, the SS Hsin-Fung, Chief Officer Gordon, described some of the ensuing action: ‘One of the Russians got a shot in her bow and is now aground in shallow water. She was hit five times in all and another of the Russians was hit three times. The Algerine, a British vessel, sustained no serious damage and only took two shots through her stoke-hold ventilators … the USS Monocacy had been up river on patrol work, and as she came down men on shore near the wharves opened fire on her with rifles but they were soon silenced.’ The Iltis lying off Tongku Railway Station suffered severely from the fire of the Northwest Fort and lost 8 men killed and nine wounded, but shortly afterwards moved down river and took up a position near the Algerine and together they engaged the fort, which they silenced in two hours.

16–17 June 1900, viewed from the south west, showing the combined attack by gunboats and storming parties and the capture of the forts themselves

The capture of the North Fort at Taku in an imaginary scene by the German artist, Fritz Neumann. Once again, the emphasis is on the German and Austrian forces. The latter distinguished themselves but lost nine men through the explosion of an underground mine. By the time the allies entered the North Fort, it had been abandoned by the Chinese garrison. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Word was now sent to the allied landing parties to commence the assault on the forts. Advancing in echelon of columns they arrived at the Northwest Fort around 4.30am. Five minutes later there was a tremendous explosion as an allied shell struck one of the Chinese magazines which blew up. British and Japanese troops scaled the parapet and captured the fort and by 5.00am the Chinese garrison had fled. The gunboats now turned their attention on the North Fort and the landing parties found it to have been abandoned. Both the forts on the north bank were now occupied by allied troops, the North Fort by the Japanese and the Northwest Fort by the British. Other allied gunboats lying just below the dockyard at Taku engaged the South and Southwest Forts, while the guns of the North Fort were also trained across the river. At 6.05am there was a large explosion in the South Fort, which was occupied shortly after by the Germans and Russians who had crossed the river. The last of the defences was in allied hands by 7.00am. A total of 904 allied soldiers and sailors had taken part in the operation and casualties had been slight; the British lost one killed and nine wounded while the Russians had five officers and 28 men killed and another 60 wounded. While the allied vessels had sustained some damage, it was minor and the most momentous naval event was the capture of four German-built Chinese torpedo-boat destroyers lying at anchor, by a small naval contingent led by Commander Roger Keyes at 1.30am.

Tientsin was considered an important commercial city by foreign merchants. It was well situated on the Peiho River at the junction with the Grand Canal approximately 30 miles distant from Taku. In 1900 the Foreign Concession consisted of three distinct western communities: British, French and German. Another community of Japanese business people was developing into a fourth foreign enclave. The environment they created was very civilised with handsome buildings, roads, gas lights, parks, and churches, and was completely separate from the native Chinese. When the rebellion erupted the city was an obvious target.

Viewed as an important base of operations for any advance on Peking, it was vital that the city be secured. Seymour had gathered his force here before heading north and on 13 June, shortly after his departure, allied troops began to arrive including 1,700 Russian infantry, 150 mounted Cossacks and 4 field guns under Lieutenant Colonel Anisimoff. Aware of this build-up the Boxers cut the telegraph wire to Taku on the 15th and occupied the Native City. On the previous day a courier had arrived from Peking reporting that all mission houses in the Western Hills, and the Summer Legation had been burnt. Also on 14 June the Russians sent a force to Chun Liang Cheng to hold the station. There were estimated to be in the range of 10,000 Boxers and Imperial troops with 60 modern guns in and around the Native City of Tientsin.

Another version of the capture of the one of the Taku forts. The marshes surrounding the forts, particularly on the landward side of the Northwest and North forts, presented an obstacle to the allies but were overcome with little difficulty, and several of the forts were abandoned without a fight. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Captain Edward H. Bayly of HMS Aurora, one of the garrison in Tientsin, noted in his journal on 16 June: ‘The Boxers made an attack on Settlement early in morning and set fire to houses … they had cover from Native City from native houses until close to Concession. The Boxers also attacked the Railway Station, but were driven off by Russian guard’. A train was sent out towards Tongku but came under heavy shell fire and was forced to return. On 17 June another train was sent out to repair lines and found itself cut off by a large body of Chinese. The troops on board opened fire with a 6-pdr gun and were able to return. An attack was made the same day by allied troops on the Chinese Military College just as the Chinese began to fire the first shells into the foreign settlements. The College was captured and set on fire and a battery of 3-in. guns taken.

Barricade of sacks of rice near the Emens residence, Tientsin, photographed by Nathan J. Sargent in June 1900. Walter Scott Emens, an American merchant and local judge, was Nathan Sargent’s employer at the trading company. One British naval officer commented that barricades were put up in various places but that few were of any real service although they kept some people employed and out of mischief. (Peabody Essex Institute, Salem, MA)

Over the next six days the Concession was subjected to almost continuous bombardment and the Chinese made attacks on the railway station and other points, but were beaten off by allied troops from a total garrison of 2,400 troops. Within the foreign settlements themselves, the civilians had built barricades and earthworks, many of them constructed under the direction of Herbert Hoover, the future President of the United States. The cellars of the Municipal Hall, considered bomb-proof, were hastily adapted to accommodate women and children. There was a little relief when some of the besieging force moved north to block Seymour’s retreat, relaxing the pressure on Tientsin although the bombardment resumed, as Captain Bayly noted on 21 June: ‘A heavy bombardment. Having only the abominable 9-pdr muzzle-loading field gun and 6-pdr quick-firing available, can do little to annoy or silence guns in Native City. The black smoke gives away the 9-pdr, and its range is poor. The 6-pdr quick-firing is useful in scattering parties of Chinese to the westward.’

The Tientsin Volunteers photographed by Nathan J. Sargent, one of the volunteers. This unit was composed primarily of businessmen. One naval officer wrote: ‘The Volunteers, also at first, rendered service, and some of the mounted ones patrolled efficiently. The ‘Home Guard’ as a body of residents called themselves, were not of any use … the real commencement of the siege soon weeded out the numbers of people who had been so “eager” to display their martial ardour.’ (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

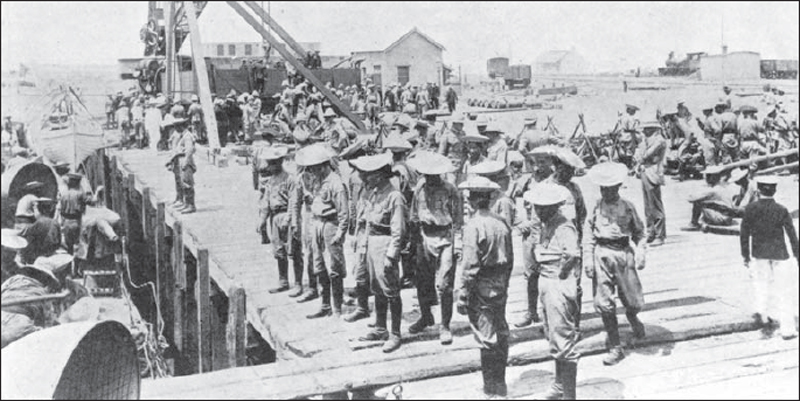

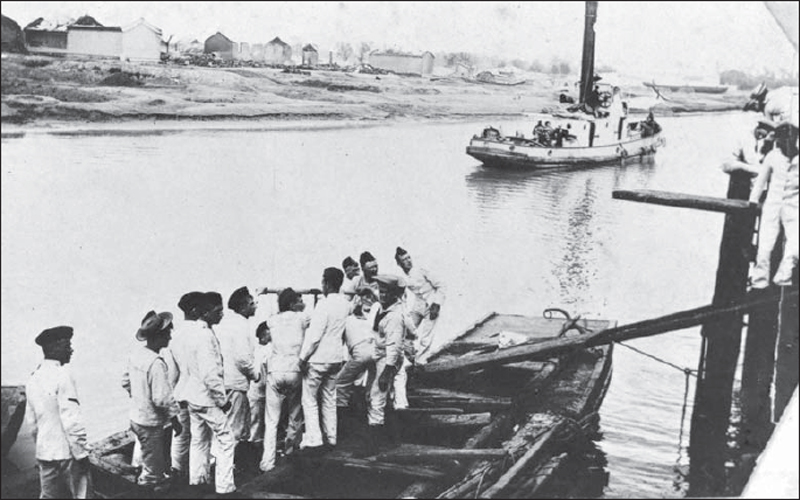

The Weihaiwei Regiment landing at Taku from Hong Kong in a photograph published in August 1900. They provided good service under British officers at Tientsin having reached the city on 24 June. They also took part in the attack on the Hsiku Arsenal to relieve Seymour’s force. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

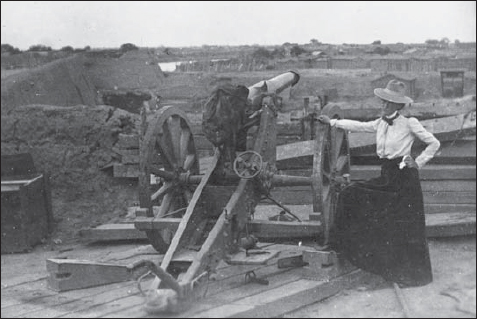

Mrs Lou Hoover standing by one of the guns in the defences of Tientsin during the siege. Her husband, Herbert, the future President of the United States, was a mining engineer who played an important part in the siege and was responsible for laying out many of the fortifications. He supervised the Chinese in erecting street barricades made from sacks of rice, sugar and peanuts taken from local warehouses, His wife volunteered as a nurse in the hospital established in the Tientsin Club. (Herbert Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa)

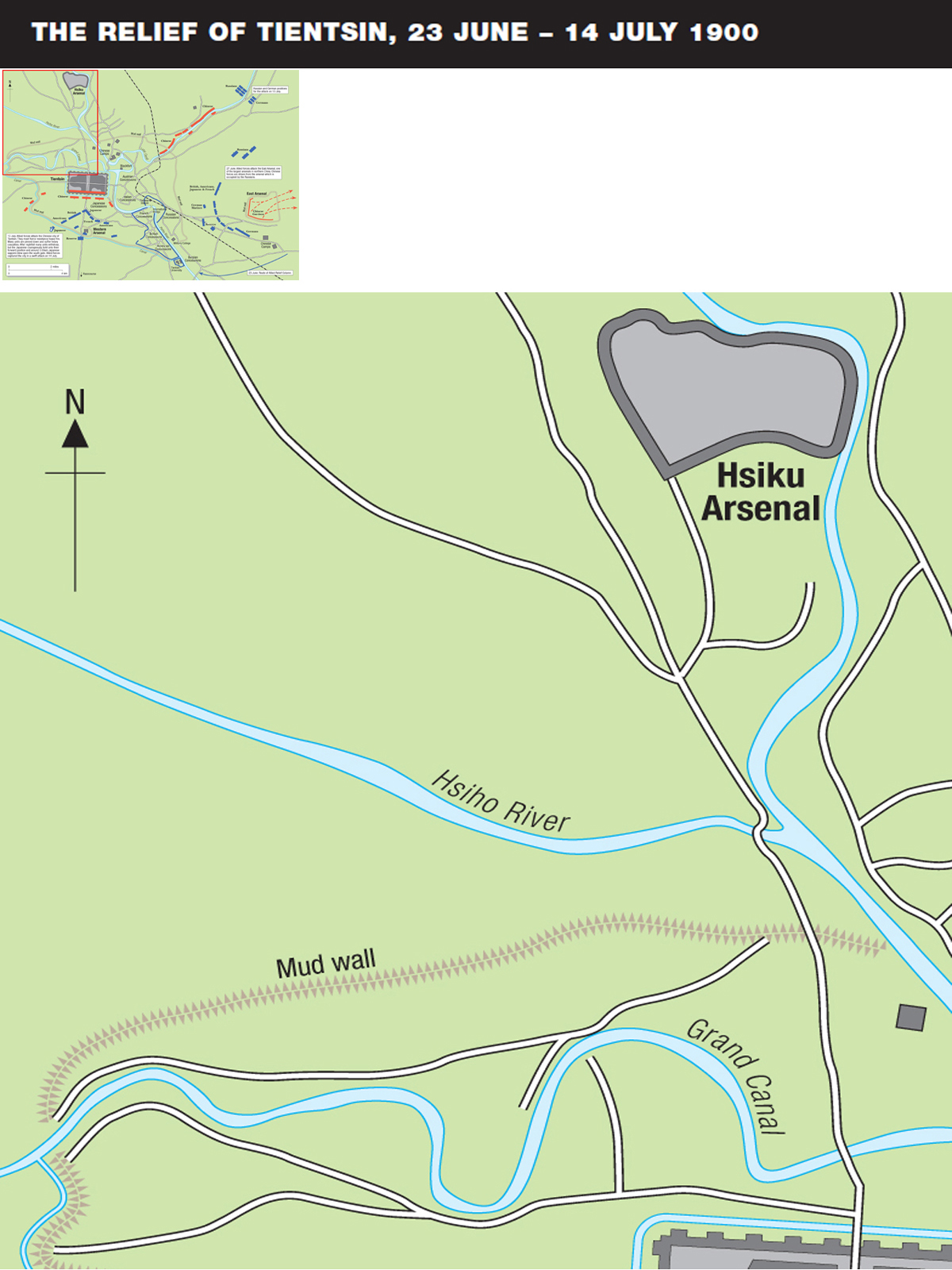

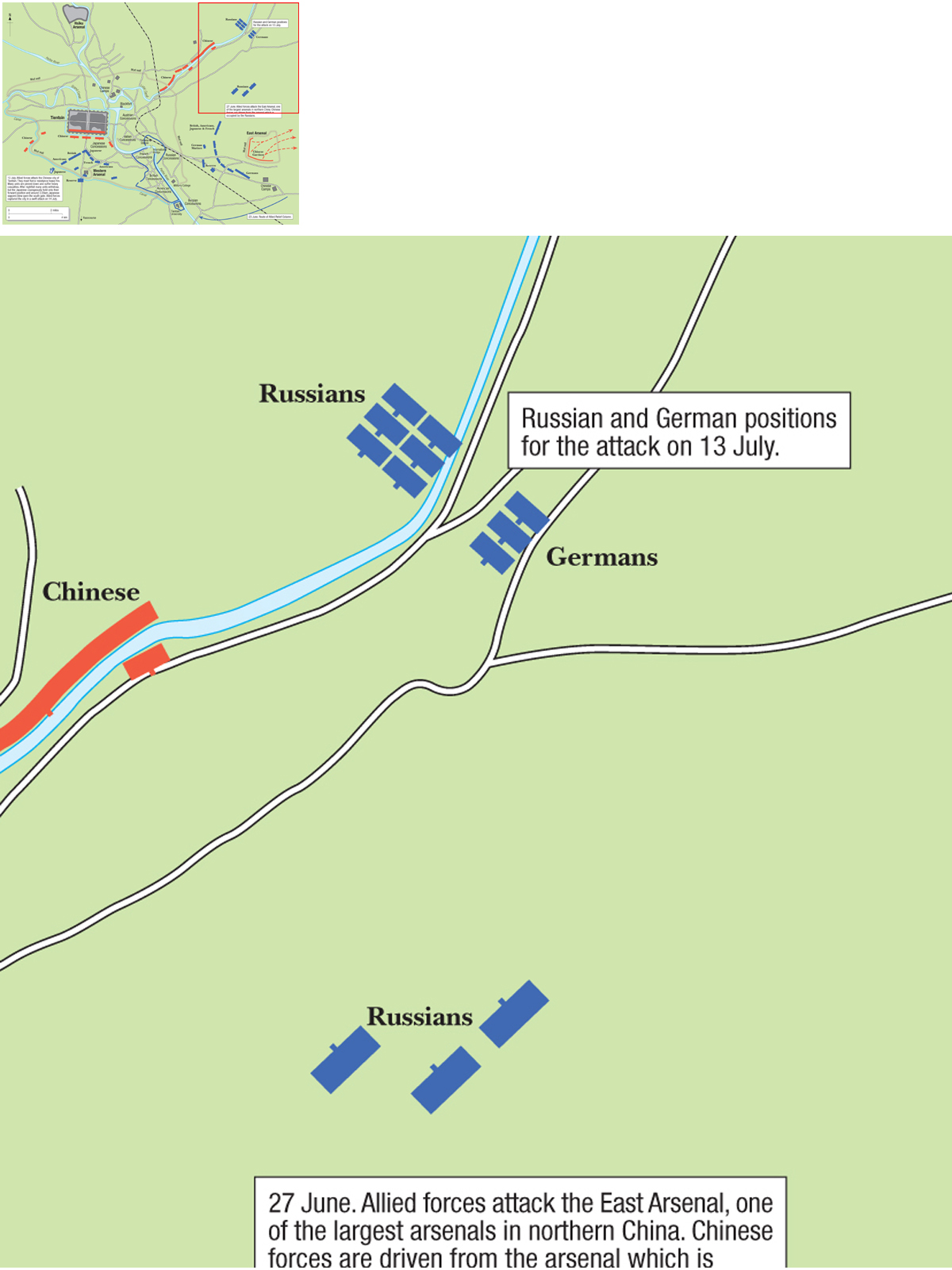

An advance force of 500 allied troops from Taku attempted to break through to Tientsin but were checked about four miles from the foreign settlements and had to fall back. Meanwhile north of the city, Seymour’s force was attempting to return. Preparations were made by the garrison to assist Seymour and as many troops as could be spared were sent out, leaving precariously few defenders. Fortunately, the situation was alleviated when 8,000 allied sailors, marines and soldiers finally broke through the Chinese lines from the south and entered Tientsin on 23 June, and on the following day, a group of Russians under General Stessel, and the First Chinese Regiment, known also as the Weihaiwei Regiment, arrived in the city. Seymour’s column was found at the Hsiku Arsenal by Cossacks and escorted back to Tientsin, arriving on the 25th to find much of the city in ruins and the streets barricaded. Many of the buildings in the Concessions had been damaged or destroyed either by shellfire or by fire. The increased force now available enabled the allies to go on the offensive and they destroyed the Tientsin Arsenal on 27 June and other places occupied by the Boxers, but on 28th the Chinese resumed their bombardment and from then on until 12 July Tientsin was once again under some form of siege. Both sides attempted to gain the upper hand, the Chinese staging an unsuccessful attack on the railway station on 4 July. The allies recaptured the Hsiku Arsenal which had been taken by the Chinese, on the 9th, and a three hour battle took place on the 11th which resulted in numerous allied casualties.

A photograph entitled ‘Silencing the enemy’s artillery’, shows Lieutenant Drummond, Royal Navy, and the 12-pdr gun crew from HMS Terrible in action at Tientsin; they had been at the siege of Ladysmith earlier in the year. Captain Edward Bayly noted that the arrival of this gun was a most welcome addition as their only other gun, a 9-pdr, gave away their position because of the thick smoke from its black powder. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

‘Illustration of the Charge of the 11th Infantry Regiment during the Destruction of the South Gate by Our Army when Attacking Tientsin Castle’. Coloured lithograph printed on 20 August 1900, and published three days later by Fukuda of Tokyo. Most Japanese prints of the period were based purely on imagination with no resemblance to actuality. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

A contemporary photograph published in 1900 and captioned ‘Just rushed by allied troops – a Chinese Palisade outside the city – a favourite sniping spot’. Tientsin was besieged for 27 days starting on 17 June and ending with its relief on 14 July, and while its citizens were not totally cut off from the outside world like their counterparts in Peking, they endured equal hardships. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

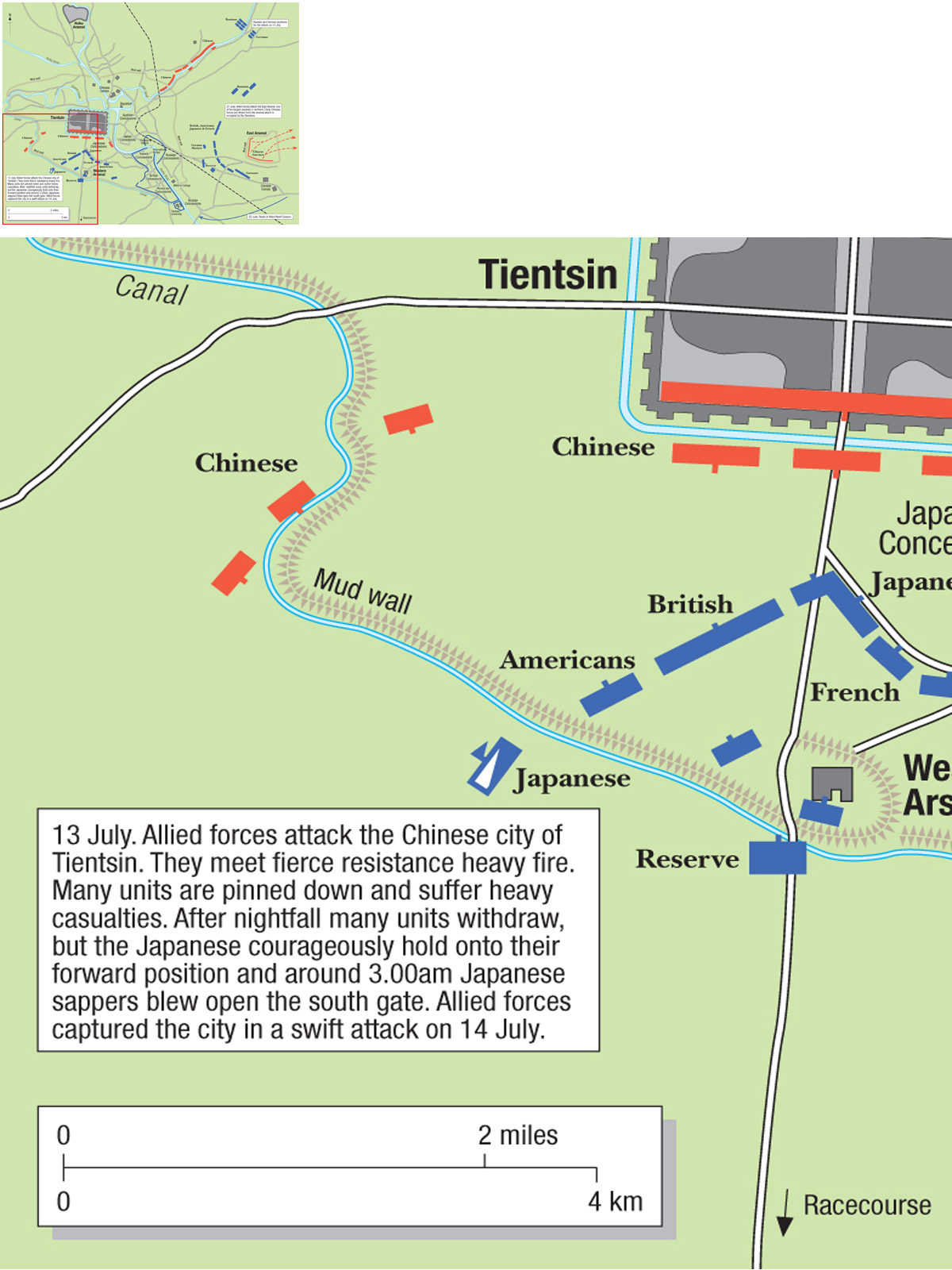

Finally, on 13 July the allies attacked the Chinese Native City. The attack was made from two directions. On the right were the Russians along with a few Germans and French who moved around to the east and north; the left attack consisted of Japanese, British, Americans and other allies, and the remaining French who moved out from the Settlements and worked their way around to the southwest and up to the South Gate of the city. The attack commenced around four in the morning and as the allies moved in, they were met by a blistering fire. The walled city was captured the next day at a very high cost to the allies but they took a terrible revenge on the Chinese for the rumoured murder of all the foreigners in Peking, news of which had reached the allies just prior to the attack. The capture of Tientsin was a terrible blow to the Chinese and it was made worse by the death of General Nieh Shih-ch’eng, considered by many to have been the ablest of the Chinese commanders.

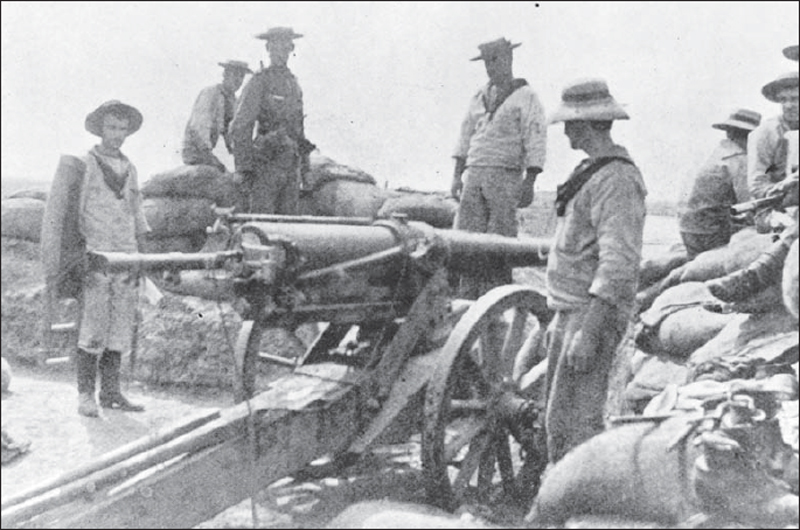

Allied soldiers and sailors on the Peiho River at Tientsin photographed by Nathan J. Sargent. The Peiho was the main artery from the coast inland to Peking and its mouth was controlled by the forts at Taku. The main railway line also paralleled the river from Tongku to Tientsin. The second relief expedition under General Gaselee followed the Peiho all the way to the capital in August 1900. Note the ruined buildings on the opposite bank. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

‘Illustration of the Attack of the Environs of Shishu by All the Nations of the Allied Armies’. Coloured lithograph printed on 28 June and published on 2 July 1900 by Tsunajima Momojiro. Shisu was a fortress and arsenal in Tientsin at the junction of the Peiho River and the Grand Canal. It was destroyed by the allies on 27 June 1900, after the Chinese had left. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

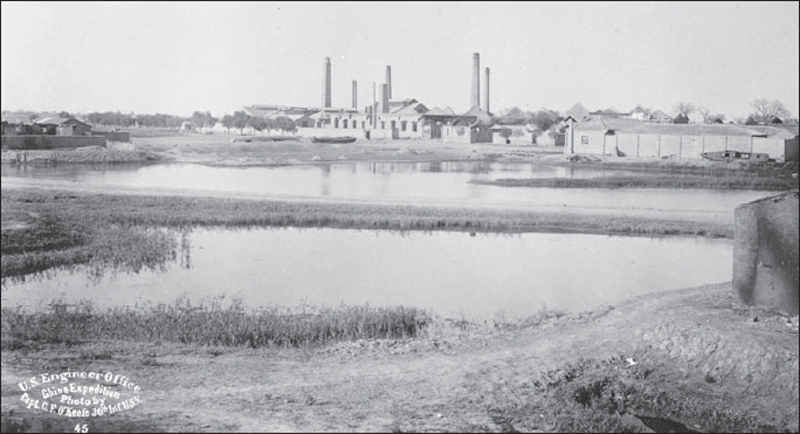

One of the Chinese arsenals at Tientsin as photographed by C.F. O’Keefe in July 1900 after Tientsin had been relieved. Around Tientsin were the main Chinese arsenals including the ones at Hsiku and Han Yang. The building at Han Yang was the only one not destroyed in the rebellion. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)