Most of the fighting in Peking ended on the 14th, but on the following day the American forces advanced to attack and occupy the Imperial and Forbidden cities, from whose walls the Chinese were still firing sporadically. The American commander, General Chaffee, had not yet received an order from the American government that with the Legations relieved no American troops were to take any further aggressive action. In the attack on 15 August one gate was blown in and the troops poured into a courtyard dominated by a tower over another set of gates from which the Chinese began firing. The Americans returned fire and brought up guns to knock down the gates. This process was repeated several times gate by gate. Faced with the final gate before the Forbidden City the US troops received the order to withdraw. General Chaffee was furious. Casualties had been suffered, among them the redoubtable Captain Reilly of the artillery who was killed by a sniper around 9.00am. The Forbidden City was not entered by the allied forces until 28 August.

Hole created in the wall of the Imperial City by British Troops as it appeared in a photograph by the Royal Engineers. This hole was very close to the British Legation compound. Two companies of the Royal Welch Fusiliers were sent to hold the Llama Temple in the Forbidden City about half a mile from the British Legation but a hole first had to be made in the south wall to allow access. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

As allied guns were still hammering away at the walls and gates on 15 August, the Dowager Empress disguised as a peasant women, accompanied by the Emperor, some Grand Councillors and various other members of the court, climbed on some rickety carts and fled northwards out of the capital. Over the next two months this retinue, which gradually grew in size, wandered from place to place covering a distance of 700 miles before settling at Sian, the capital of Shensi Province, in late October. According to one Chinese observer, Chuan Sen, an assistant professor in the Imperial College, shortly after the escape of the Dowager Empress, Prince Ch’ing, knowing that the city could not be defended, distributed flags of truce to the Chinese soldiers and ordered them to be put on the city wall. The Empress did not return to Peking until 6 January 1902.

However, on 3 September 1900 Prince Ch’ing and Li Hung-Chang returned to Peking invested with the full powers to act as Plenipotentiaries in dealing with the allied powers to arrange a peace settlement. On the day of Prince Ch’ing’s arrival, Fred Whiting, the artist for the London Graphic, noted the scene: ‘He was met some three miles away from the North Gate of the city by a detachment of Japanese cavalry. While at the gate, where his soldiers were disbanded, a detachment of the 4th Bengal Lancers was waiting to take its place in the procession … Prince Ch’ing wore ordinary Chinese costume, not even wearing his red button cap and peacock feathers – the signs of high rank.’

The last vestige of Boxer resistance in Peking collapsed on the same day the Empress departed, when the Peitang Cathedral was finally relieved. Thereafter the soldiers of the allied armies were free to roam the city plundering and looting whatever took their fancy. Even the Legations participated, holding auctions of loot. The main event during the next few weeks was a grand parade held on 28 August by the victorious forces to impress their defeated foe. To drive their point home, the allies decided to hold their parade in the Forbidden City, sacrosanct in the eyes of the Chinese. Sydney Adamson, the correspondent for Leslie’s Weekly and the Evening Post, described the moment: ‘The British officers kept up their reputation as the cleanest, smartest, and best-horsed of all troops. In point of cleanliness in clothing and accoutrements, and in general bearing, the “Tommies” and the Indian troops were an easy first. When the Russian column filed through to the swing of a martial air we were all surprised to see that they were moderately clean. Then some of the Japs followed, headed by the general and staff. They were all smart and well uniformed.’

Li Hung-Chang, the Chinese official who was selected to negotiate a peace settlement with the allies although he was described at the time as a ‘wily old Mandarin … there is good reason for believing that he has been in constant communication with the Empress and Boxer chiefs all through the disturbances’. This photograph was taken in Hong Kong on his way to Shanghai and was published in September 1900. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Funeral Service for Captain Henry J. Reilly, 5th United States Artillery, as photographed by C.F. O’Keefe. Reilly was killed in action on 15 August 1900 and buried at the US Legation on the following day. He was fifty-three when he died and was a veteran of the Spanish-American War, where he saw action in the Santiago campaign. During the advance on Peking, his battery was involved in the actions at Yangtsun, Hosiwu and Matau. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

By now more and more foreign troops were swarming into Peking, which was almost devoid of the native population. Elsewhere villages and towns had been burnt and heavily looted by allied troops whose only thought was for revenge. Any place suspected of showing anti-foreign sentiment was ‘visited’ by detachments of the allied force to teach the local inhabitants a lesson.

British staff at the Llama Temple, Peking, photographed by the Royal Engineers after the siege. The allied forces extensively plundered Chinese buildings and temples looting and robbing them of treasures, many of which ended up in western museums. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

Avenue of Statues, Ming Tombs, Peking, photographed by C.F. O’Keefe in 1901 and showing Troop L, of the 6th United States Cavalry on a sightseeing expedition. Following the relief of Peking, American troops served in the army of occupation until their departure from China in May 1901. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

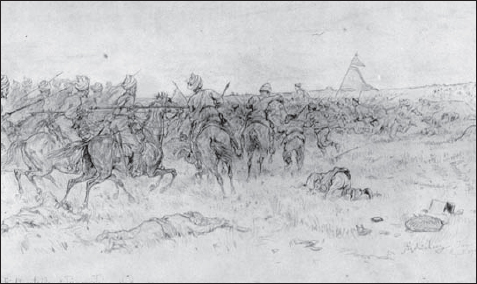

Bengal Lancers in action, from a drawing by Frank Feller. The lancers were an important arm of the allied force and were well suited to the open low-lying land of northern China. They participated in several of the punitive expeditions following the relief of Peking. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

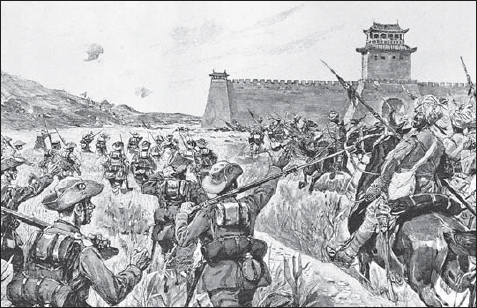

Between 8 and 25 September no less than four punitive expeditions were sent out, the first arriving at Tu Liu Ts’un, regarded as a centre of Boxer sympathy, 15 miles south-west of Tientsin. The Field Force Orders for the attack on this town stated that ‘Information having been received that the town of Tiu Liu, 22 miles distant from Tientsin, is occupied by Boxers, who [have] long held their headquarters at that place, three columns consisting of troops as separately detailed in the orders for each column under the general command of Brigadier General A.R.F. Dorward CB, DSO will proceed to operate against that place, on the dates given in the detailed orders for each column’. The result – a town left in smouldering ruin. Three days later it was the turn of Liang-Hsiang, which was stormed and 170 of its citizens summarily executed after a hasty trial. After the arrival of Field Marshal Count von Waldersee, the supreme allied commander, at Taku on 25 September, these expeditions were stepped up. The German general commented that the only thing that worried him was ‘our slackness with the Chinese’. Unfortunately, many innocent civilians were killed in the process as the allies pursued their vicious policy of punishing the population. Throughout the rest of 1900, expeditions were dispatched to persecute the former enemy, while executions of suspected Boxers and others implicated, such as the murderer of von Ketteler, continued.

Allied troops attacking Liang-Hsiang. This was a walled city located 18 miles south-west of Peking. The force that attacked the town on 11 September 1900 consisted of 800 Germans and 45 troopers of the 1st Bengal Lancers. Following a heavy bombardment, the Boxers fled in the process of which 30 were killed. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Charge of the 1st Bengal Lancers sketched by Schönberg outside Tientsin on 19 August and reproduced in the Illustrated London News on 17 November 1900. The accompanying caption quoting from the artist’s letter stated that, ‘In this action thirty-seven prisoners were taken, of whom thirteen were “Boxers.” Two hundred Chinese were killed during the fight.’ (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

In the south of China, particularly the Yangtse Valley, the occupation was more of a policing action to prevent the spread of anti-foreign sentiments, while in the north, it was decided to occupy the forts at Shanhaikwan at the terminus of the Great Wall. However, as the forts were very strong and believed to be well defended, it would require a number of heavily armoured ships to reduce them. A force of a dozen battleships and armoured cruisers was selected. The British gunboat Pigmy was sent to the fort bearing a delegation from Count von Waldersee to invite the Chinese commander, General Cheng, to surrender the forts for temporary occupation. They found that the garrison of 3,000 men was about to withdraw having already received word from the Russians at Port Arthur that they had dispatched 4,000 troops to occupy the forts. Cheng, fearing the arrival of the Russians, withdrew his garrison, leaving some crewmen of the Pigmy to man the forts. Upon hearing of the situation, Admiral Seymour sailed north on the Alacrity and arriving on 2 October, found the Russians outside the forts and the 18 men of the Pigmy inside. With diplomatic flair, Seymour managed to head off a confrontation by offering to share the forts among the allies. Shortly after, the flags of the seven allied nations were raised on one of the forts.

On 17 October, Waldersee arrived in Peking, and within a few days, Sir Claude MacDonald had departed the capital for a new posting in Tokyo, to be replaced by Sir Ernest Satow. The next day, a large allied force bore down on the city of Paotingfu, a hotbed of Boxer fanaticism. Failing to surrender to General Gaselee’s requests, the town was invested and leading officials executed as reprisals for the murder of some missionaries. This was, Waldersee’s method of sending a message to the Chinese and it received the full blessing of the Kaiser, although such excesses did not sit easily with all the allies. Von Waldersee continued to prosecute a harsh and vengeful policy against the Chinese into 1901. And he had the forces to do it. By 1 April 1901 the allied occupation force in China consisted of 300 Austrians, 18,181 British, 15,670 French, 21,295 Germans, 2,155 Italians, 6,408 Japanese, 2,900 Russians and 1,750 Americans; a total of 68,659 men.

On 26 February two prominent Boxer leaders were executed while others such as Prince Tuan were banished for life. Further Chinese opposition was rapidly withering, but by this time tensions were emerging between the occupying powers. On 12 March British and Russian troops almost came to blows over a railway siding in Tientsin. The Russians were the least popular and many feared that they had designs on Chinese territory in North China. The Germans were distrusted by the French and their commander, von Waldersee, was most unpopular, while the British were accused of not pulling their weight. Although clashing among themselves their policy towards the Chinese remained consistent. They were guided by three main objectives: the punishment of all Boxers and any Chinese officials viewed as having been sympathetic to their cause during the war; Chinese reparations to cover the cost of the allied expeditions; and all existing treaties were to be revisited to benefit the foreign powers. The Chinese delegation that had been nominated in September 1900 were presented with an eleven-point programme.

After much debate and revision of these conditions, the peace treaty was signed on 7 September 1901. It called for, among other things, the formal apology to Germany and Japan for the murders of Baron von Ketteler and Chancellor Sugiyama, the prohibition on arms and armaments entering the country, and the garrisoning of twelve places to safeguard communications. The Chinese were required to pay an indemnity of $333 million over a period of 40 years, In 1908, the United States government passed a resolution remitting to China its share of the indemnity in the form of scholarships for Chinese students, and in 1924 remitted all further payments.

But there was still the issue of access to China’s markets and the allies took differing views on this ranging from the ‘open door’ policy as promoted by Britain, the United States and Germany, and the protectionist stance of nations such as Russia who wanted to establish spheres of influence in areas such as Manchuria in which Russian troops were already present on the pretext of policing the area. Japan also had her eyes on this region. A new treaty was signed with Britain in September 1902 which opened China up for even more trade. The following year saw Japan obtaining further concessions in the country, and the stage was set for a showdown between this upstart nation and Russia over Manchuria which flared up into full-scale conflict in 1904.

Some have seen the Boxer Rebellion as much as an uprising against the ruling Manchus as against the foreigners. As one writer put it, ‘If the Boxer Uprising really was a “rebellion”, against what constituted authority did the Boxers rebel? The answer can only be, the Manchu government of China.’ To many Chinese, the Manchus were considered aliens to the country and the events of 1900 can be seen as a precursor to the eventual overthrow of the Manchu Dynasty in 1912. Following the rebellion, the Manchu government had initiated a reform policy in 1902 and made plans to develop a limited constitutional government similar to the Japanese model. This was not enough and a coalition of Chinese students trained overseas, merchants and domestic dissidents began a series of uprisings in 1911, but the army applied only limited pressure and eventually came to terms with the revolutionaries. In February 1912, a revolutionary assembly in Nanking elected the first president of the Chinese Republic.

Field Marshal Count von Waldersee reviewing the allied troops photographed by the Royal Engineers. This review was held on New Years’ Day, 1901, when the allied occupying forces paraded in front of the Imperial Palace. Von Waldersee himself played an insignificant part in the campaign as he arrived after the relief of Peking, but he was directly responsible for some of the reprisals against the Chinese as retaliation for the murder of von Ketteler and other civilians. (Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Collection)

Inspection of the Bengal Lancers by Count von Waldersee at the south-west gate of Peking, in a scene witnessed by John Schönberg. The German Field Marshal reviewed the lancers shortly after their return from an expedition. According to the caption in the Illustrated London News, ‘the troopers presented a splendid appearance, and the Austrian attaché, General Hauptmann, said he had never seen such a fine body of men’. (Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library)

Throughout the next 30 years China continued to be plagued by foreign influence in certain parts of the country, particularly by the Japanese, who obtained the former German possessions following World War One. This friction between China and Japan burst into in full-scale war in the early 1930s and continued on and off until the end of the Second World War when China was finally able to throw of the shackles of foreign influence once and for all. Today, the Boxer Rebellion must be viewed with other revolts such as the Indian Mutiny or the Egyptian Revolt of 1882, as a nationalist struggle to overthrow encroaching colonial expansionism by Europe and the west, an expansionism based on ignorance of Chinese society, culture and religion.