BENJAMIN DISRAELI

December 21, 1804–April 19, 1881

LONDON—The Earl of Beaconsfield, after an illness of less than a month, died at an early hour this morning.

He was first attacked during the last week of March, with gout and violent asthmatic symptoms, both of which troubles were soon alleviated by his skillful medical attendants. Since his prostration, bulletins giving reports of his condition have been issued several times each day. Early this morning his physicians were at his bedside, but the utmost exertions of the medical gentlemen failed to have effect, and the great statesman expired peacefully. He was perfectly conscious to the last.

Among the Jews who were driven out of Spain at the close of the fifteenth century, when the inquisition and other persecutions forced from that land the most industrious and active races that lived in it, were the ancestors of Lord Beaconsfield. They found a home and opportunities to restore their fortune in Venice. While living in Spain they had been forced to adopt a Christianized surname, but as soon as the shores of Venice were touched the name was changed to D’Israeli, a designation which unmistakably indicated the race to which they belonged.

They remained in Venice more than 200 years before one of the family sent his youngest son to England to seek his fortune. He married and settled in Enfield, a few miles from London. His only child, Isaac, was the father of Lord Beaconsfield. Isaac married in 1802 the daughter of George Basevi, a Justice of the Peace in Sussex, who bore him four children, of whom Benjamin (Dec. 21, 1804) was the second.

It does not appear that Isaac D’Israeli took even ordinary care to perfect the education of his boy. Universal testimony declares that the son was remarkably precocious and of very bright mind, but he was sent to a boarding-school in Winchester, to the house of a Unitarian minister, and to an attorney’s office instead of to Harrow, Rugby, Oxford or Cambridge. Lord Beaconsfield, in many ways so remarkable, is singularly so in this, that he was one of the few eminent English statesmen who had not been at Oxford or Cambridge.

Rarely has a literary success so sudden as the young Mr. Disraeli’s occurred in literature. He was only 22 years of age when “Vivian Grey” was launched anonymously into the London world. Vivian Grey, the character, was the author himself, who remained anonymous. The novel depicted the course of a young man of genius and ambition who was without friends and aspired to political honors. On its title page was this prophetic quotation: “Why, then, the world’s mine oyster, Which I with sword will open—.” It was a sufficient index of his subsequent career.

Flushed with the success of “Vivian Grey,” the young author went abroad, returning to find himself a lion in the society of London.

Count D’Orsay drew a picture of him during this period which represents a very handsome man, such as might ornament and delight any London drawing-room. His hair was of silken blackness and fell in ringlets about his neck and forehead; his dress coat was of black velvet, lined with white satin, and he carried an ivory-handled cane, inlaid with gold, and ornamented with a tassel of black silk.

Men laughed at his affectation, and generally held him in low esteem, but women approved of his peculiarities, and the more discerning of them predicted that time would see him a great man.

England, in 1831, was in the last stage of the struggle for Parliamentary reform. Then began the public life of this remarkable man who was to astonish and puzzle the world for 50 years. A son of Earl Grey, then the Premier, had been put forward in the Borough of High Wycombe, as a candidate for Parliament, and the young Mr. Disraeli entered into the contest against him. His nomination was proposed by a Radical, and a Tory seconded it, but the united votes of the two parties failed to elect him.

A second candidature, and a third, ended in like manner.

This latter was the occasion of his famous quarrel with [the Irish member of Parliament Daniel] O’Connell. O’Connell had allied himself with the Whigs, in spite of the fact that the Whigs had formerly treated him with great contempt, and thus appeared in the forefront against Mr. Disraeli, who singled him out for an attack as an “incendiary,” a “traitor,” and a “liar in word and action.”

O’Connell’s retort is known everywhere. “He,” said the Irishman, “possesses just the qualities of the impenitent thief who died upon the cross, whose name, I verily believe, must have been Mr. Disraeli. For aught I know, the present Mr. Disraeli is descended from him, and with the impression that he is, I now forgive the heir-at-law of the blasphemous thief who died upon the cross.”

Mr. Disraeli’s first reply to this was a challenge to O’Connell’s son, Morgan. Bridled in this effort, he retorted in a letter to the London Times which was regarded at the time as fuss and fury. He got to have a reputation of being a vain and frothy young man, in too great a hurry to succeed.

With the beginning of Victoria’s reign the public life of Benjamin Disraeli took a sudden turn. In accordance with constitutional usage, the accession of a new sovereign to the throne was followed by a general election, and in this Mr. Disraeli—through stupid conduct on the part of the Whigs, it is often maintained—found himself in Parliament, the junior member from Maidstone.

Parliament reassembled in November, 1837, and three weeks had not passed before the young member delivered his maiden speech.

It was on the Irish election petitions, and in direct reply to O’Connell, whom he had now come, as he promised, “to meet at Philippi.” Again and again he was interrupted, and finally was compelled to sit down amid laughter and jeers. His last words were these: “I have begun several things many times, and I have often succeeded at last. I will sit down now, but the time will come when you will hear me.”

As early as 1839 he had expressed himself on the subject of electoral reform. In July, he astonished certain classes by a declaration that denounced the tendency of Government to centralization and the monopoly of power in the hands of the middle classes. To the lower classes he appealed to yield up the Government to the upper, declaring that “the aristocracy and the laboring class constituted the nation.”

Mr. Disraeli’s power in England as a leader of the Tory Party dates from 1847. The sudden death of Lord George Bentinck, a year later, left him the acknowledged head of the Protectionists. Out of failures by the Whigs on free trade measures, he gathered strength, and the year 1852 found him far advanced in the esteem of Parliament, where he became Chancellor of the Exchequer and leader of the House of Commons. When Parliament assembled in November, and the conflict over free trade soon arose, [William] Gladstone, his rival, won the day.

Out of power, Mr. Disraeli remained in his place in the House, and on all occasions, when his patriotism was appealed to, gave Lord Palmerston his loyal and earnest support.

With the changes of 1858, which more or less had their origin in the Orsini conspiracy against the life of Napoleon III, Mr. Disraeli was intimately associated. There had been in France loud complaints against England for permitting a conspiracy to be hatched on her own soil against a neighboring power, and certain published statements indicated that the French Government was of like feeling on the subject.

Under these circumstances, Lord Palmerston moved for leave to bring in a bill relating to conspiracy to murder. Lord Palmerston’s proposal became extremely unpopular, and Mr. Disraeli, reading public feeling that had so intensified itself against the bill, declared against it.

The Spring of 1859 found Mr. Disraeli again in office as Chancellor of the Exchequer and leader of the House. But Mr. Disraeli and his colleagues were soon out of power again over the contentious issue of Parliamentary reform.

Lord Palmerston’s sudden death in October, 1865, when the returns of a general election had scarcely ceased to be received, left the Government without a head. Lord Russell was called upon, but in less than a year he resigned and Lord Derby formed an Administration with Mr. Disraeli again leader in the House. During the recess of 1866–67 it became known that the ministry had decided to introduce a Reform bill.

Six Reform bills since 1852 had been introduced, and all had failed. This one did not, and in August, 1867, it received the Queen’s signature. Mr. Disraeli’s work for it was of a tremendous order. He was not only the author of the bill, but his speeches numbered 310. By this law the right of suffrage was extended to all house-holders in a borough and to every person in a county who had a freehold of 40s. It enfranchised nearly a million of men.

Following its passage came Mr. Disraeli’s elevation to the Premiership, and the first question that met him was Irish disestablishment. A long debate ended in his defeat: he refused to abandon his position, and Parliament was dissolved. The new election showed a strong majority for the Opposition, and in December, 1868, Mr. Disraeli and his colleagues resigned in favor of Gladstone.

Gradually the Gladstone Ministry was living out its lease of power. Matters went on until February, 1874, when it found a majority of 50 against it and fell. Mr. Disraeli was called upon to form a new Cabinet, and then saw himself for the first time strong in a majority on which he could rely, and possessed of the personal confidence of the Queen.

From this time on his great career is a matter of vivid public recollection, and needs only to be indicated briefly here. England had fallen into disrepute among the nations; her want of participation in the policy of Europe was a subject of ridicule. Under him, she laid aside her insular character and obtained position as a military power in Europe; she acquired Cyprus and gained authority in Asiatic Turkey.

Victoria did not transfer her seat of empire from London to Delhi, as he had foretold that she might do, but he made her Empress of India; he summoned Indian troops into Europe to support England; he made Asia Minor acknowledge her sway, and in buying the Suez Canal shares he secured the short way to India. After all this, he was voted out of power again, and his old rival came in. He went into retirement and wrote “Endymion” to find a publisher at £10,000.

Mr. Disraeli, about the year 1840, was married, his wife being the widow of his old friend, Wyndham Lewis, who was the senior member for Maidstone when he was the junior. She was more than ten years his elder, and brought him a large fortune. It was a singularly happy union for both. He has more than once owned his great indebtedness to her. She had an enthusiastic interest in all his undertakings, and was the soul of devotion to all his purposes. In 1868, when a Peerage was offered him, he declined it for himself, but prayed that the Queen would make his wife Countess of Beaconsfield, and she bore that title until she died in 1873.

OTTO VON BISMARCK

April 1, 1815–July 30, 1898

BERLIN—Prince Bismarck died shortly before 11 o’clock this evening. Details of his death are obtained with difficulty because of the lateness of the hour, the isolation of the castle, and the endeavors of attendants of the family to prevent publicity of what they consider private details.

The death of the ex-Chancellor at the age of 83 comes as a surprise to all Europe. There was apprehension when the sinking of the Prince was first announced. But when the daily bulletins chronicled improvement in his condition and told of his devotion to his pipe, the public accepted his doctor’s assertion that there was no reason why Bismarck should not reach the age of 90 years.

The Saturday papers in Europe dismissed Bismarck with a paragraph, while his condition was overshadowed in the English papers by the condition of the Prince of Wales’s knee.

The Bismarck family, with its estate at Friedrichsruh, traces its lineage back to the 13th century. The present title, that of Fürst von Bismarck, dates from 1871. This title will be borne by Bismarck’s eldest son, known up to now as Count Herbert.

The news of the death of Prince Bismarck became known throughout New York City early in the evening. At all places where Germans congregate, at clubs, meetings, and in numerous East Side cafés, the subject was talked of all evening.

“Bismarck is dead,” said Gerthue Maaf, one of the oldest members of the Liederkranz club, “but only in the body. His fame is imperishable as the stars.”

The old-fashioned Prussian country house in which Otto von Bismarck, the future consolidator of Germany, saw the light on the 1st of April, 1815, has become a place of pilgrimage for tourists of all nations. His birth just when all Germany was rising to meet the last effort of Napoleon have made some persons picture him as a modern Hannibal, self-vowed from his cradle to eternal enmity against France.

Although the active, bright-eyed child of course had little idea of his own future greatness, there is little doubt that the surroundings of young Otto’s boyhood left a deep and lasting trace upon his mind. As a child he would hear old country gentlemen telling of the wasted lands that marked Napoleon’s destroying march through conquered Prussia in 1806 and the tremendous retribution that avenged this havoc seven years later when the Fatherland arose against the tyrant. He would listen to men from Berlin, Frankfurt, or Cologne lamenting the fatal dissensions which made the great German race almost a cipher in the politics of Europe.

He would later see the proofs of the weakness produced by Germany’s fragmentary condition, while at the same time his keen eye would detect the latent strength which might make her invincible, could those fragments be wielded into one compact whole.

While her future leader was climbing trees and leaping ditches, Germany was passing through the most momentous period of her modern history. The movement which cleared German soil of its French invaders in 1813 and dethroned Napoleon a few months later was a victory for the Teutonic race. The conquerors began to ask themselves why they should not be united permanently.

It was in the crisis of this great national excitement that Bismarck’s public career began.

This great apostle of unquestioned authority was always intolerant of authority himself. His Saxon Boswell, Dr. Moritz Busch, has chronicled the first flashes of that haughty and indomitable spirit which would one day trample in the dust the pride of Austria and France. Being called to account while a student at Gottingen for some breach of university rules, Bismarck swaggered into the presence of the horrified President with a rakish student cap and a sorely stained velvet jacket, an enormous bulldog at his heels.

Such actions, coupled with his reckless exposure of himself to all weathers and his wild gallops across country at the imminent risk of his neck, earned him the nickname of “Mad Bismarck,” and made many prim old gentlemen regard him as a harum-scarum lad who would come to no good.

Toward the end of 1833 he quitted the University of Gottingen for that of Berlin, and in June, 1835, he was admitted to the bar.

In 1847 he made his first appearance in the Parliament of Berlin as delegate of the nobility of his district. Into a circle of solemn mediocrities burst like a thunderbolt this dashing, fiery rebel. “I come among these nonentities like pepper,” said he, with grim enjoyment.

This was no exaggeration. The towering figure, the massive head thrown haughtily back, the brawny arms folded defiantly, the stern, piercing eye, the deep, challenging voice, and the crushing sarcasm, became well known in Berlin. Enemies multiplied as rapidly as acquaintances, and the new delegate quickly became, as he himself declared, “the best-hated man in all Prussia.”

This was hardly surprising. The popular excitement, which would culminate in the great tidal wave of popular movements of 1848, had reached its height. Between such a man and such a movement there could be no sympathy. No one could have been a more typically complete aristocrat than this scion of a house of secondary rank, whose own mother had belonged to the bourgeois class. Throughout his career, all popular movements were anathema to Bismarck.

Bismarck seemed to hold that the King ought to do what he pleased without letting his people say anything at all. In early 1848 he asserted that “the world could never hope for any lasting peace until all large cities, those hotbeds of democracy and constitutionalism, were swept from the face of the earth.”

In this period Bismarck beheld many things worthy of note. France had again proclaimed herself a republic. Austria was sitting sullenly amid the ruins of her ancient system. Russia was casting her mighty shadow across the whole of Europe. Germany lay a formless heap of incoherent atoms, each with its own toy sovereign and its own army of half a dozen men.

While the pillars of the world were shaking around him, Bismarck was enjoying one of the few intervals of quiet happiness which checkered his stormy life. Few sweeter love stories have been told than that which ended on the 28th of July, 1847, in the union of gentle Johanna von Puttkammer with the bearded giant whose name was a by-word throughout all Prussia.

It is fortunate that so many of Bismarck’s letters to his wife remain to show the man as he really was. Anyone who had seen him only as the world sees him might stand amazed at the hearty, boyish merriment, the simple, childlike faith, the heartfelt tenderness revealed by this man whom 99 persons out of 100 regard as an apostle of “blood and iron.”

Yet even while the future Chancellor of the German Empire was helping his new bride up Swiss hillsides and rowing her over Italian lakes, there were signs across Europe of the mighty events that would come 20 years later, among them a suggestion of universal suffrage and a rupture between Prussia and Austria.

Amid these warring influences one man stood forward. That man was Otto von Bismarck, who would mastermind the wars that unified the German states, a unification that did not include Austria, into a powerful German Empire under Prussian leadership.

One can understand Bismarck’s opposition to “German unity” at a time when that unity meant the subordination of his native Prussia and all the other States of Northern Germany to that ill-corded bundle of Czechs, Hungarians, Croats, Poles, and Ruthenians, which called itself the Austrian Empire.

In 1861 the death of his insane brother made the Prince Regent King in fact as well as in name. The new sovereign was a sworn friend of Bismarck, and one of his first acts was to appoint to the Premiership the man whom he now knew to be as great in mind as in body.

This was the beginning of the end. Austria, perceiving too late that the substance had fallen to Prussia, grew angry and menacing. She shifted her center of gravity to the eastward and ceased to be a German power.

Any ordinary man would have been carried away by this astounding triumph and by the sudden change from universal hatred to the adoration of all Prussia. But Bismarck saw that France must follow Austria before the Prussian Kingdom could become the German Empire.

All this time the secret maturing of his mighty project went steadily on. “In the streets of Paris,” wrote a traveler who saw Bismarck at the Paris Exhibition of 1867, “the tawny hair beneath the peaked helmet, the long, sweeping, reddish-brown mustache, the stern eyes, the ruddy, blonde complexion, the strange, grim expression soon became familiar. He bore himself haughtily and silently amid the fantastic festivities of Paris.”

In truth, his next entrance into “the metropolis of the universe” three years later was no smiling matter. France struggled longer than Austria, but in vain, and the same month that witnessed the surrender of Paris saw the coronation at Versailles of “William I, Emperor of Germany.”

Throughout that conflict Bismarck’s proverbial energy outdid itself. “Often,” says Dr. Busch, “when just out of bed, he began to think and work, to read and annotate dispatches, to study the newspapers, give instructions to the Councilors and other colleagues, put questions on the most various State problems, and even write or dictate.

“Then came the study of maps, the correction of papers that he had ordered to be prepared, the jotting down of ideas with the well-known big pencil, the composition of letters, the news to be telegraphed or sent to the papers for publication, and amid all this the reception of unavoidable visitors.

“Not till 2 or even 3 P.M. did the Chancellor, in places where a halt of any length was made, allow himself, a little breathing time, and then he generally took a ride in the neighborhood. Then to work again until dinner at 5 or 6 P.M., and in an hour and a half at latest he was back at his writing table, where midnight often found him reading or noting down his thoughts.”

The Emperor’s coronation was likewise that of Bismarck. But, like Napoleon and the Czar Nicholas, Bismarck lived too long. His later years were one incessant and fruitless struggle with the problems of political economy that had overmatched Frederick the Great and the revolutionary spirit that had defied even the autocrats of Russia.

When the enforcement of his arbitrary system of political economy drove yearly across the sea myriads of those sturdy laborers who were the lifeblood of Germany, Bismarck sought to enable these emigrants to become colonists without ceasing to be German citizens.

The “Iron Chancellor” began that series of annexations which established Germany in New-Guinea and the Samoan Isles, and extended the shadow of her imperial flag over 750 miles of coast along Western and Southwestern Africa. Bismarck clung to the idea of founding another German empire abroad.

“Once a German, always a German,” said he. “When a man can cast away his nationality like a worn-out coat, I have nothing more to say to him.”

When the aged Kaiser died, it was suspected that Bismarck’s ascendency under the Emperor Frederick would be less than it had been under William, but he remained Chancellor and held his former place as the foremost figure in European diplomacy.

Finally Frederick died and his son William came to the throne. Matters went from bad to worse until March 18, 1890, when Bismarck finally resigned.

The personal character of this remarkable man remains a subject of dispute, thanks to the extravagant praises of his friends on one side and the calumnies of his foes on the other. In his domestic relations his worst enemies can find nothing to blame, but they denounced his public acts as those of a tyrannical, bloodthirsty man.

Tyrannical he was, but a hard-hearted man would not have stood with tears in his eyes beside the body of his favorite dog, or have all but lost his own life in saving that of his drowning servant. And a bloodthirsty man would have reveled in the horrors of war instead of doing his utmost to alleviate them.

QUEEN VICTORIA

May 24, 1819–January 22, 1901

COWES, ISLE OF WIGHT—Queen Victoria is dead. The greatest event in the memory of this generation, almost the most stupendous change in England that could be imagined, has taken place quietly, almost gently.

The end of this splendid career came at exactly 6:30 yesterday in a simply furnished room in Osborne House. This most respected of all women, living or dead, lay in a great four-posted bed. Within view of her dying eyes there hung a portrait of the Prince Consort.

A few minutes later the inevitable element of materialism stepped into this pathetic chapter of international history, for the Court ladies went busily to work ordering their mourning from London.

For several weeks the Queen had been failing. On Wednesday she suffered a paralytic stroke, accompanied by intense weakness. It was her first illness in all her 81 years, and she would not admit she was sick.

Albert Edward, Prince of Wales for more than 59 years, is now Edward VII of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and Emperor of India.

The reign of Queen Victoria, who came to the throne in 1837, was the longest in English history; indeed, it was one of the longest in the history of Europe. Victoria’s more than half century of reign began when she was a grown-up woman and legally of age.

In a greater sense, however, was this reign a memorable one in English history. Literary endeavor and the search for knowledge in no other single reign, save that of Elizabeth, made such splendid contributions to the stock of new facts and written words that men will not let die. The scientific results achieved by the mind of man in the age of Victoria stand alone as the wonder and blessing of mankind.

No former sovereign reigned over so extensive a British Empire. In her time vast areas were added in Africa, India, and the Pacific, so that it was never quite so true as in her time that the British Empire was one on which the sun never set.

Though the royal house to which Queen Victoria belonged was that of Hanover, from the house of Stuart Victoria claimed her crown.

In Kensington Palace on the 24th of May, 1819, was born the future Queen of England.

When the child was six months old she was taken by her parents to Sidmouth, on the Devonshire coast, and here the Duke, her father, soon met his death. He had come home one day with his feet wet, and had stopped to play with his daughter before changing his boots. A fatal inflammation of the lungs ensued.

For many years, Victoria’s position as heir apparent was doubtful. Even so late as 1830, the life of William IV stood between her and the throne.

Victoria had not been brought up with any assurance that she was heir to the throne. Strict orders were in force that no one should speak to her on the subject.

But when William IV became King nearing 65 years of age, statesmen then saw as all but inevitable that this little girl, who was 12 years old, was to be the future Queen.

It was thought time for her to know her position. The story told is that her governess conveyed the information by placing in one of her books a genealogical table. Examining it, the Princess said to the governess, “I see I am nearer the throne than I thought.”

In England 18 is the age at which a royal Princess reaches her majority. Victoria passed this period on May 24, 1837. Less than a month afterward, on June 20, at 2:20 A.M., the King breathed his last. Immediately after this a carriage containing the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chamberlain departed for Kensington Palace. What followed has been described in the “Diary” of Miss Wynn:

“They knocked, they rang, they thumped for a considerable time before they could arouse a porter at the gate. They rang the bell and desired that the attendant of the Princess Victoria might be sent to inform her royal Highness that they requested an audience on business of importance.

“The attendant stated that the Princess was in such a sweet sleep that she could not disturb her. They then said: ‘We are come on business of State to the Queen, and even her sleep must give way to that.’ In a few moments she came into the room in a white nightgown and shawl, her nightcap thrown off and her hair falling upon her shoulders, her feet in slippers, tears in her eyes, but perfectly collected.”

It was arranged that a Council should be held that day at Kensington. In Greville’s “Diary” the following account of this Council is given, and Greville was not a man given to emotion:

“Never was anything like the first impression she produced, or the chorus of praise and admiration which it raised about her manner and behavior, and certainly not without justice. It was very extraordinary, and something far beyond what was looked for. Her extreme youth and inexperience, and the ignorance of the world concerning her, naturally excited intense curiosity to see how she would act on this trying occasion.

“She was plainly dressed and in mourning. After she had read her speech and taken the oath for the security of the Church of Scotland, the Privy Councilors were sworn, and, as these old men knelt before her swearing allegiance and kissing her hand, I saw her blush up to the eyes, and this was the only sign of emotion that she evinced.”

On the following day occurred the ceremony of the proclamation, when the Queen made her appearance at the open window in St. James’s Palace. At Kensington a range of apartments were set apart for her use, and there she lived until she left for Buckingham Palace.

She opened the first Parliament of her reign in November, and the following June she was formally crowned in Westminster Abbey. Harriet Martineau, an eye-witness, has described that scene with much felicity.

“The throne,” says she, “covered, as was its footstool, with cloth of gold, stood on an elevation of four steps in the center of the area.

“About 9 the first gleams of the sun started into the Abbey, and presently traveled down to the peeresses. Each lady shone out as a rainbow. The brightness, vastness, and dreamy magnificence of the scene produced a strange effect of exhaustion and sleepiness.”

Albert, Prince Consort of England, was the second son of Ernest, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, and was three months younger than Victoria.

Prince Albert first saw the Princess Victoria in the Spring of 1836, when he made a visit to England. The two are believed to have parted reluctantly. Victoria, in a letter to her uncle, begged him to “take care of the health of one now so dear to me.”

Albert well understood how the strict etiquette of the Court obliged the Queen to take the initiative, and hence, on his second visit, in October, 1839, when the purpose of his visit was clearly understood, he waited anxiously for some sign of the Queen’s decision in his favor. This he had the happiness to obtain on the second evening of his visit, at a ball, when she gave him her bouquet, and he received a message from her that she desired to speak with him on the following day.

In the following year occurred the wedding.

One of the most charming domestic pictures that royal lives have afforded is furnished in the married life of Albert and Victoria. Prince Albert was a man of honest purposes and devoted affections; he was endowed with noble ambitions guided by intelligence. Painting, etching, and music were accomplishments that afforded amusement to both, and the Prince was a man of taste and skill in landscape gardening. He loved a country life and early hours. To these tastes the Queen learned to conform.

The difficulties encountered at the outset of this union were incident to the peculiar relations of the Queen and Prince. Head of the family though the Prince was in his position as husband, his place in public affairs was necessarily subordinate. The common judgment is that he bore himself with good sense and dignity in this trying situation. The Queen, however, soon showed her determination that in all matters not affairs of State, the Prince was to exercise paramount authority.

The Queen became the mother of nine children. At the time of her first jubilee, which was celebrated with extraordinary splendor on a perfect June day in 1887, the Queen had thirty-one grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

The domestic life of the Queen for the 20 years her husband lived was singularly happy. Fate seemed to shower upon her every blessing to which a woman could aspire.

In the eighteen-sixties came the illness of the Prince Consort. In December 1861 he breathed his last.

Victoria’s life after her husband died was one of quiet seclusion. Her people saw little of her, and the projects honoring his memory were, for the most part, the only ones in which she manifested particular interest. In London the colossal Albert Memorial was erected, and in 1867 the Queen laid the foundation stone of the Albert Hall of Arts and Sciences.

In 1863 the Prince of Wales completed his 21st year, and was married.

In 1877 a new eminence was acquired by the Queen. She was made Empress of India.

When Victoria assumed the Crown, English statesmen had been for some years occupied with measures of electoral reform.

Under the reform bill passed in 1832, 56 boroughs in England, containing populations of less than 2,000 each, were disfranchised, 30 others were reduced to one member only, and 42 new ones were created. These boroughs which had been disfranchised were rotten boroughs. A new era in Parliamentary government was about to open.

Later on in her reign reform bills became familiar subjects in Parliamentary life.

Reform acts of 1884 and 1885 have been pronounced “the most extensive reform ever attempted in England.” They applied to Scotland as well as England, and were extended to Ireland. England thenceforth has possessed practically universal suffrage.

Also an issue during Victoria’s reign were the Corn Laws, which imposed tariffs on imported grain, thus raising food prices and prompting opposition from city residents.

Save for the war with China, begun in 1839, England had no war on her hands until the portentous cloud arose on the Bosporus in 1853.

The war in China was a war for trade. The precise occasion for declaring war was the Chinese demand for the surrender of opium. Peace was not formally secured until July, 1843. By the terms of this treaty England was to receive from China the sum of $21,000,000, and Hongkong was ceded to her in perpetuity.

The war in the Crimea was an outgrowth of designs respecting Turkey long entertained by Russia.

A dispute arose between Russia and France as to the possession of the holy places in Palestine. A commission appointed by Turkey decided in favor of Russia. Further claims on Turkey were then made by Russia.

The Sultan of Turkey then appealed to his allies, and the English and French fleets advanced for his protection. By September of 1853 English and French ships were in the Dardanelles; in October Turkey had declared war against Russia.

Operations in the Crimea began with the landing of the armies of the allies in September, 1854. They forced the Russians to retreat to Sebastopol, and in October the attack on the fortress was begun.

The incidents of this celebrated siege need only be named here. They include the battle of Balaklava, with the charge of the light cavalry, which Tennyson has celebrated; Florence Nightingale’s work in the hospitals, tales of great suffering from cold weather, the death of the Czar Nicholas, and the peace treaty concluded in March, 1856.

England lost in this war nearly 24,000 men. Those killed in action and who died of wounds numbered 3,500; cholera caused the death of 4,244, and other diseases nearly 16,000.

One year later there occurred in India the first incidents of that famous mutiny, the suppression of which would tax the best energies of England’s administrators and soldiers for more than two years.

A result of this mutiny was the formal transfer of the direct Government of India from the East India Company to the British Crown. In November, 1858, Victoria was proclaimed in the principal places of India, and thus became the sovereign to that country. The proclamation of Victoria as Empress of India occurred in May, 1876.

Had the reign of Victoria no other great achievements besides those of cheap postage and rapid travel by steam, it would still deserve to be ranked among the great epochs of English civilization. Later years, however, have seen the penny-postage system superseded by the telegraph—even a telegraph that connects continents otherwise divided by great oceans—and still later ones have seen the telephone disputing with the telegraph its claims to usefulness in the service of man.

Connected by a natural link with these inventions has also been the expansion of the iron industries of England. In 1837 the total yearly output of crude iron in England was only about 1,000,000 tons. Now it is over 8,000,000 tons. Twenty years after 1837 an invention was applied in iron manufactures which has wrought great changes in the world. This was Sir Henry Bessemer’s process for making steel by blowing air into molten pig iron. This process has caused the price of steel to be greatly reduced, so that steel now competes with iron for many purposes.

If we turn now to the literature of this reign a noble and lasting output will be found, including books produced by men of science, like Darwin, who have given us books as epoch-making as any the mind of man ever produced. It is not for contemporaries to say if the verse of Tennyson and the prose of Macaulay, Carlyle, and Thackeray will live on, but the chances are good for a reasonable degree of immortality.

The poetry of Mrs. Browning almost exclusively belongs to this reign, and so does that of her husband. Matthew Arnold’s first success, the poem on Cromwell, dates from 1843. Swinburne was born in the year of Victoria’s accession. Dickens’s first volume, “Sketches by Boz,” came out in 1836. Ere the genius of George Eliot should become known twenty years were to elapse. Carlyle had written many of his essays, but was still waiting for the day when literature should raise him above actual want.

NICHOLAS II OF RUSSIA

May 18, 1868–July, 17 1918

LONDON—Nicholas Romanoff, ex-Czar of Russia, was shot July 16, according to a Russian announcement by wireless today.

The central executive body of the Bolshevist Government announces that it has important documents concerning the former Emperor’s affairs, including his own diaries and letters from the monk Rasputin, who was killed shortly before the revolution. These will be published in the near future, the message declares.

The text of the Russian wireless message reads in part:

“At the first session of the Central Executive Committee, elected by the fifth Congress of the Councils, a message was made public that had been received by direct wire from the Ural Regional Council concerning the shooting of the ex-Czar Nicholas Romanoff.

“Recently Yekaterinburg, the capital of the Red Urals, was seriously threatened by the approach of Czechoslovak hands, and a counterrevolutionary conspiracy was discovered, which had as its object the wresting of the ex-Czar from the hands of the council’s authority. In view of this fact, the President of the Ural Regional Council decided to shoot the ex-Czar, and the decision was carried out on July 16.

“The wife and the son of Nicholas Romanoff have been sent to a place of security.

“Documents concerning the conspiracy which was discovered have been forwarded to Moscow by a special messenger. It had been recently decided to bring the ex-Czar before a tribunal to be tried for his crimes against the people, and only later occurrences led to delay in adopting this course.”

There have been rumors since June 24 that ex-Czar Nicholas of Russia had been assassinated. The first of these stated that he had been killed at Yekaterinburg by Red Guards. This report was denied later, but this denial was closely followed by a Geneva dispatch saying that Nicholas had been executed by the Bolsheviki after a trial at Yekaterinburg. This report seemed to be confirmed by advices to Washington from Stockholm.

The next report was what purported to be an intercepted wireless message from M. Tchicherin, the Bolshevist Foreign Minister, in which it was stated that Nicholas was dead. Still another report was to the effect that he had been bayonetted by a guard while being taken from Yekaterinburg to Perm. Of all these reports there was no direct confirmation.

There seemingly is no question that yesterday’s dispatch is authentic. It comes in the form of a Russian wireless dispatch, and as the wireless plants of Russia are under the control of the Bolsheviki, it appears that it is an official version of the death of the former Emperor.

NIKOLAI LENIN

April 22, 1870–January 21, 1924

MOSCOW—Nikolai Lenin died last night at 6:50 o’clock. The immediate cause of death was paralysis of the respiratory centers due to a cerebral hemorrhage.

Lenin was 54 years old. He belonged to the class known as the small nobility. He was brought up in the Orthodox faith and educated to be a professor. His father was a State Councilor. The family name was Ulianoff. “Lenin” is a pen name. Lenin’s wife, Nadjeduda Constantinova Krupshata, was with him at the end.

—Walter Duranty

While Russia declined into economic ruin, while millions starved to death within short distances of rich lands which were formerly the greatest wheat producing regions of Europe; while civilization disappeared and some districts fell even into cannibalism; while the country with the greatest agricultural resources in the world had to be fed from abroad; while preventable disease made havoc such as has been unknown for centuries—all this time Lenin easily held his power in Russia, and even kept international followers, who pleaded with their own countries to follow the example of Russia.

The Russian masses seemed to have the same feeling toward Lenin which they had formerly had toward the “Little Father.” They used to revere the Czar and to find excuses for him while hating his functionaries. In the same way the ordinary Russian found no fault with Lenin and laid the ruin of the country to those around him and to circumstances that he could not control.

While the peasant and workingmen had a superstitious reverence for Lenin, those who were nearer to him had a loyalty founded on their knowledge of his absolute disinterestedness and the intensity of his convictions. They felt that he worked hard, lived ascetically, scorned riches and was inspired by a fierce enthusiasm unmixed with baser motives.

The fact that his doctrines did not work had been several times reported to be a contributing cause to his fatal illness. No amount of fanaticism could blind him to the fact that they had not worked out right. He had readjusted those doctrines and temporarily suspended some of his axioms, in the hope of reviving industry and keeping the people fed during the interim caused by some inexplicable delay in the arrival of Utopia.

For every one legally assassinated in the French Revolution, he had caused the judicial murder of hundreds—all, of course, for the good of Russia. This was frankly admitted and defended as an essential step in clearing the stage for the communistic millennium. The age of blood was to be a preliminary to the age of gold.

His greatest disappointment was the failure of the international movement, the inability of Communists in other countries to overthrow their Governments and put the world under the rule of Soviets in the early stages of the revolution.

But temporizing with “capitalistic” Governments has been allowable, under Lenin’s system of conduct, from the beginning. Lenin was deliberately placed in Russia by the German General Staff in 1917 to put Russia out of the war. He was in Geneva when the Czar’s Government broke down. His transportation across Germany was arranged by the German high command as a strategic maneuver.

Lenin was perfectly willing to accept this help from a capitalist Government. He believed that the Russian revolution he foresaw would be followed by uprisings of the proletariat all over the world, the German revolution being one of the first. But the event proved that the Germans had calculated correctly. Lenin did put Russia out of the war. He did not succeed in his hope of a proletarian triumph in Germany. The German revolution came later from military and economic causes, not as a result of Soviet infection.

At two periods in his career Lenin was the most important man in Russia. The earlier time was during the attempted revolution of 1905. He left his mark on Russia heavily in 1905, because the insurrection which he then led checked the steps which had been taken to put Russia on a constitutional basis. Lenin was a perfect specimen of the doctrinaire in 1905, as in 1917. His devotion to dogma would not permit him to look with favor on half measures. At a later period he was ready to barter and trade in practical measures, but he would hear of no compromise where a political dogma was involved.

Already in 1905 Lenin and the Social Democratic Party, which he founded, had worked out the theory of government by a small revolutionary minority, commanding the majority and working in their interest.

The first Soviet was formed in Petrograd in 1905 after the granting of the Constitution. It was to the activity of this Soviet and the influence of Lenin that Russia owed the gradual curtailment of the Constitution granted by the Czar in 1905. The actual uprising by the followers of Lenin was quickly suppressed, but it gave reactionaries the argument that any concessions offered to the Russian people would cause revolt, and that the safety of the Government lay in the practice of despotism according to the old rules.

When he was 17 years old, Lenin’s brother Alexander was executed for complicity in a terrorist plot against the life of Alexander III. In the same year Lenin finished his course in the Simbirsk Gymnasium and entered the Kazan University. He was banished from Kazan a few months later for taking part in a students’ riot.

His offense was overlooked, however, and in 1891 he was a student in the University of St. Petersburg, where he studied law and economics. He also studied in Germany.

In 1895, arrested in St. Petersburg as a dangerous Socialist, he was exiled to Siberia for three years. In 1900 he went abroad. Living much of the time in Switzerland, he was the head of the group of exiled and condemned revolutionists of Russia and other countries. Of Lenin’s life in Switzerland, M. J. Olgin wrote:

“A smoky back room in a little café in Geneva; a few score of picturesque-looking Russian revolutionary exiles, men and women, seated around uncovered tables over glasses of beer or tea; at the head of the table a man in his forties, talking in a slow yet impassioned manner; and now and then an exclamation of disapproval, an outburst of indignation among a part of the audience, which would be instantly parried by a flashing remark of the speaker, a striking home with unusual trenchancy and venom—this is how I see now in my imagination the leader of the Bolsheviki, the great Inquisitor of the Russian social democracy, Nicolai Lenin.

“There is nothing remarkable in the appearance of this man—a typical Russian with rather irregular features; a stern but not unkindly expression; something crude in manner and dress, recalling the artisan rather than the intellectual and the thinker. You would ordinarily pass by a man of this kind without noticing him at all. Yet, had you happened to look into his eyes or to hear his public speech, you would not be likely to forget him.

“His eyes are small, but glow with compressed fire; they are clever, shrewd and alert; they seem to be constantly on guard, and they pierce you behind half-closed lids.”

With the overthrow of the Czar the Russian revolutionaries returned to Russia. [Alexander] Kerensky [head of the Russian Provisional Government] fell in November, and Lenin and [Leon] Trotsky set up the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” maintaining themselves in power by the slaughter of tens of thousands as counterrevolutionaries.

Maxim Gorky described the work of Lenin as an experiment in a laboratory, with the exception of the fact that it was performed on a living thing, and that, if the experiment did not have the expected success, the outcome would be death.

An almost complete stoppage of production, chaos in the transportation system, famine in the big cities, then in the country districts, all accompanied the Bolshevist régime almost from the beginning—effects largely due, according to outside observers, to the belief that work was no longer a necessity, but that all could live off those richer than themselves.

Spasmodic efforts to bring back production by introducing martial law with the nationalization of industries, compelling workers to do a hard day’s work at peril of their lives, were announced from time to time, but proved not to be enduring or of wide application.

Lenin’s literary output, explaining and recommending the Russian system to the rest of the world, went on unabated, in spite of the Russian collapse. The real condition of starvation and ruin in Russia was denied, and the reports of it attributed to the malice of the capitalist press.

Lenin as he was in the third year of his absolute dictatorship was described by H. G. Wells as follows in an article printed in The New York Times:

“I had come expecting to struggle with a doctrinaire Marxist. I found nothing of the sort. I had been told that Lenin lectured people; he certainly did nothing of the sort on this occasion. Much has been made of his laugh in the descriptions—a laugh which is said to be pleasing at first and afterward to become cynical.

“Lenin has a pleasant, quick-changing brownish face, with a lively smile and a habit (due, perhaps, to some defect in focusing) of screwing up one of his eyes as he pauses in his talk. He is not very much like the photographs you see of him, because he is one of those persons whose change of expression is more important than their features.”

In addressing the Russian Assembly of Political Education in 1921, Lenin, for the first time, made a partial admission of defeat and error.

“In part,” he said, “under the influence of military problems which were showered upon us and of the seemingly desperate condition in which the republic found itself under the influence of these circumstances, we made the mistake of deciding to pass immediately to communistic production and distribution.

“We decided that the peasants, according to the system of requisition of surplus, would give us the needed quantity of bread, and we should distribute it to the factories and workshops and arrive at communistic production and distribution. I cannot say that we drew up thus definitely and clearly any such plan, but we acted in that spirit.

“This, I am sorry to say, is a fact. I am sorry because an experience which did not take long has convinced us of the mistakenness of the proceeding, which was in contradiction to what we had previously written in regard to the transition from capitalism to socialism, and has convinced us that without passing through a phase of socialistic supervision and control you cannot rise even to the first degree of communism.”

Attempts of the Soviet Government to interest American capitalists and manufacturers in Russia had failed, both because of lack of support from the American Government and because an exploring party of American manufacturers came to the conclusion that Russia had nothing with which to pay them except promises. When hope to tempt this country to resume trade was at an end, the Soviet Government pleaded for provisions, which resulted in the sending of the American Relief Administration to Russia and the feeding of millions in that way.

There has been little news about Lenin from Russia in the last few months until recently, when there have been hints of discussion among the Communists as to his successor.

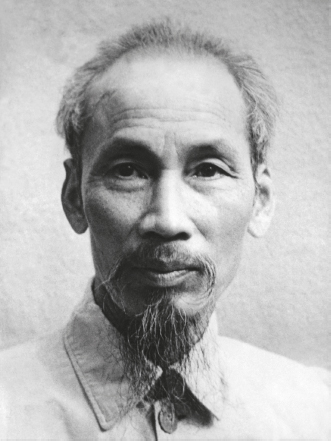

SUN YAT-SEN

November 12, 1866–March 12, 1925

PEKING—Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the South China leader, died this morning at 58 years of age.

Dr. Sun for some time had been suffering from cancer of the liver.

As the Southern leader yesterday was slowly passing into his final sleep, his headquarters in Canton announced that his troops had occupied Swatow, in the Province of Kwangtung, whence all the rebel leaders were said to have fled without giving battle.

The name of Dr. Sun Yat-sen first began to be heard in Chinese political affairs in the late 1880’s, when his vigorous pronouncements against the Manchu emperors of China reached beyond the boundaries of his native land. Since that time few men in public life have known more ups and downs, more victories, more defeats, than Dr. Sun, who won the title of the “Father of the Republic.”

To Dr. Sun was given the credit for having engineered the uprising by which the people retired the Manchus and proclaimed the republic in 1912.

When the revolution broke out prematurely in the Yangtze Valley in October, 1911, Dr. Sun was in England. He hurried back and was chosen head of the revolutionary Republican headquarters at Nanking, the rebels designating him “Provisional President of the Republic.”

Actually and officially he never was President of China, as the Manchus had merely appointed Yuan Shi-kai, as Premier in Peking, to mediate with the rebels. The result was the formal establishment of the republic in February, 1912, with Yuan Shi-kai as President, and Dr. Sun’s organization, by agreement, was disbanded.

Yuan served as President until his death in June, 1916, which occurred soon after his futile attempt to become emperor, an empty title he bestowed upon himself for 100 days. He was succeeded by Vice President Li Yuan-hung.

Again in 1921 the remnant of the original Chinese Republican Parliament of 1913, never having received any further mandate to sit, besides having been dissolved by Yuan Shi-kai, met in Canton and “elected” Sun Yat-sen “President of China.” The real President of China was then Hsu Shin-ch’ang, and he was in no way superseded by Dr. Sun.

However, Dr. Sun and his associates took control of affairs in South China, with headquarters in Canton, and they have administered an area with a population of about 40,000,000 people ever since. The total population of China is estimated to be 400,000,000.

Out of this assumption of power in the South grew what is called the “Republic of South China,” which, however, has never been recognized by any Government in the world.

Since 1922 the Sun group has been fighting, on the battlefield and in political councils, with General Chen Chiung-min, for control of the South, resulting in constant pillage, murder and turmoil there.

Dr. Sun’s father was a Christian farmer in Kuangtung Province, where Sun Yat-sen was born in 1866. Under the tutelage of Dr. Kerr of an American mission school, he learned English rapidly and took up the study and practice of medicine.

A political career had a stronger appeal to him than the profession of medicine, and with the launching of the Young China Party his active work in the affairs of his country began. One of the exciting incidents in his career came in October, 1896, while he was in London. While outside the Chinese Legation he was kidnapped. The intention, it was learned afterward, was to smuggle him to China, where there was a price on his head.

He was confined in the basement of the legation, but he was able to smuggle out a letter addressed to his former teacher, Sir James Cantle, who took the note to the Foreign Office. His liberation was effected by policemen sent to the legation by Lord Salisbury.

At the first opportunity Dr. Sun appeared openly in China. This opportunity came in 1911, as outlined above.

Perhaps his narrowest escape was in Canton in 1905. One of his plots to assassinate the Manchu officials and seize the city was betrayed, and a round-up of the leaders was set in motion. Dr. Sun fled with a band of hostile soldiers at his heels. Suddenly a door opened and he was drawn inside. The door closed as mysteriously as it had opened, and the pursuers passed on. A friendly servant in the house of a prominent mandarin had made the rescue. There, days later, the fugitive watched from a window of that same house as fifteen of his followers were put to death.

—Associated Press

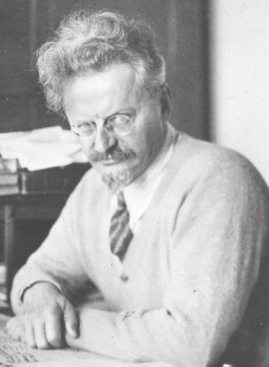

LEON TROTSKY

November 7, 1879–August 21, 1940

By Arnaldo Cortesi

MEXICO CITY—After twenty-six hours of an extraordinarily tenacious fight for life, Leon Trotsky died at 7:25 P.M. today of wounds inflicted upon his head with a pickaxe by an assailant in his home yesterday.

Almost his last words, whispered to his secretary, were:

“Please say to our friends I am sure of the victory of the Fourth International. Go forward!”

The 60-year-old exile’s losing struggle for existence continued all last night and all day today.

The assassin, Jacques Mornard van den Dreschd, for months an intimate of the Trotsky household, had a declaration written in French on his person when he was arrested yesterday. Police said that in it he told of having quarreled with his leader when Mr. Trotsky tried to induce him to go to Russia to perform acts of sabotage.

The declaration adds that the writer decided to kill Mr. Trotsky because the latter did everything in his power to prevent van den Dreschd from marrying Sylvia Ageloff of Brooklyn, who had introduced the two men to each other.

Questioned by police, Miss Ageloff declared she introduced “Frank Jackson,” as she knew him, to Mr. Trotsky in perfect good faith not knowing he had any designs on the former Soviet War Commissar’s life.

The assassin, who entered Mexico posing as a Canadian, Frank Jackson, now is said to have been born in Teheran, Iran, son of a Belgian diplomat.

With remarkable fortitude, Mr. Trotsky, despite his very severe wound, was able to grapple with his assailant and then run from the room in which he was attacked, shouting for help. He did not collapse until his wife and his guards had rushed to his aid.

The devotion of Mrs. Trotsky filled everyone who saw her with pity. This small, white-haired, retiring woman was the first to run to her husband’s aid and to grapple with his assailant. She did not leave Mr. Trotsky’s bedside for a single minute.

Joseph Hansen, one of Mr. Trotsky’s American secretaries, issued a written account of the attack. It said, in part:

“Trotsky knew the assassin, Frank Jackson, personally for more than six months. Jackson enjoyed Trotsky’s confidence because of his connection with Trotsky’s movement in France and the United States. Jackson visited the house frequently. At no time did we have the least ground to suspect he was an agent of the GPU (Russian secret police).

“He entered the house on Aug. 20 at 5:30 o’clock. He met Mr. Trotsky in the patio near the chicken yard, where he told Trotsky he had written an article on which he wished his advice. Trotsky agreed as a matter of course and walked with him to the dining room, where they met Mrs. Trotsky.

“Trotsky then invited Jackson into the study but without previously notifying his secretaries. The first indication of something wrong was the sound of terrible cries and a violent struggle in Trotsky’s study.

“The assassin apparently struck Trotsky from behind with a miner’s pick or alpenstock—the point penetrating into the brain. Instead of dropping unconscious as the assassin had evidently planned, Trotsky still retained consciousness and struggled with the assailant. As he lay bleeding on the floor later, he described the struggle to Mrs. Trotsky and Secretary Hansen. He told Hansen: ‘Jackson shot me with a revolver. I am seriously wounded. I feel that this time it is the end.’

“Hansen tried to convince him it was only a surface wound and could not have been caused by a revolver because nobody heard a shot, but Trotsky replied: ‘No, I feel here (pointing to his heart) that this time they have succeeded.’”

Leon Trotsky, whose real name was Leba Bronstein, was born of Jewish parents in 1879 in a small town in Kherson, Russia, near the Black Sea. His father was a chemist. He received his education in the local schools, but did not attend the university. He was expelled from school at the age of 15 for desecrating a sacred icon, an image of the Orthodox Russian Church, thus giving an early indication of his radical temperament, which led him throughout his life to attack religion as well as the other factors in the existing order of things.

While still in his teens Trotsky became a revolutionist, and began to write articles, make speeches and help in the organization of revolutionary movements. He became a disciple of Karl Marx, and gradually formulated the communistic ideas which he and Lenin later were to put into practice in Russia.

Trotsky was arrested when the 1905 rebellion was put down and was exiled to Siberia. But he escaped after six months on a false passport made out in the name of Trotsky, said to have been the name of a guard. This was the way in which Trotsky got the name which has become known throughout the world ever since.

When the war started, Trotsky was editing a newspaper in Berlin, where he had found many friends among the radicals and had had help in writing a history of the first Russian revolution. Exiled from Germany as a “dangerous anarchist,” he found refuge in Vienna.

Next he went to Zurich, Switzerland, and then on to Paris. He began the publication of a radical sheet called Our World, but it was suppressed, and Trotsky was expelled from France. He was escorted to the Spanish frontier, but was arrested. On his release he sailed for New York with his wife and two sons, Leo and Sergius.

Trotsky and his family arrived here on the steamship Monserrat from Barcelona, Spain, on Jan. 14, 1917, and they went to live in a three-room apartment on Vyse Avenue, the Bronx. He found work as an editorial writer on the Russian radical daily Novy Mir. While he was here he predicted that the war would result in revolution among the working classes in the warring countries.

Following the overthrow of the Czar, Trotsky and his family returned to Russia. On his arrival in Petrograd he joined Lenin and the other Maximalists, or Bolsheviki, in the Left Wing of the Russian Socialists. They first supported the Kerensky government, but gradually broke away on the issue of peace. The November revolution, in which the Kerensky government was overthrown, brought Lenin and Trotsky to the top.

Trotsky became Lenin’s right-hand man, taking the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs and then Minister of War. It was in the latter capacity that his monumental achievement of reorganizing and directing the Red Army took place.

The numerical strength of the army he organized was about 1,500,000. In four years of almost constant fighting on various fronts it defeated the forces under Yudenitch, Kolchak, Denikin, the “White Army” of Wrangel in the Crimean, and the Polish Army.

Once the army was functioning smoothly Trotsky was able to turn his efforts to other fields. In 1919 he started to reorganize the railroad system, but his severe tactics alienated the employees and Lenin ultimately removed him in summary fashion. It was the first of many rumored quarrels with Lenin. When Lenin became incapacitated by illness in 1923, Trotsky was expected to step into Lenin’s shoes. His failure to do so ultimately caused his political ruin.

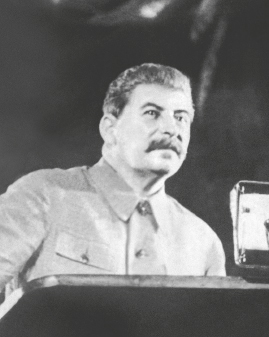

While Lenin was unable to carry on his work, the All-Russian Congress named a triumvirate to take his place. It consisted of Kameneff, Zinovleff and Stalin, who was later to prove Trotsky’s conqueror in the struggle for power.

Lenin died in January, 1924, and the inevitable fight for control of the Communist party began almost immediately after. It soon became evident that the triumvirate was too strong for Trotsky. A year later he was removed as chairman of the Revolutionary War Council, which meant his automatic dismissal as Minister of War and the beginning of the end of his political career.

The crux of his opposition, then and afterward, was on the question of “right” and “left.” Trotsky always stood for communism in the strict sense of the word, without compromise. Russia should have nothing to do with capitalistic systems of government or economics, he believed; the “world revolution” should be fostered; the well-to-do peasants should not be favored at the expense of the poorer.

In January, 1925, Trotsky went to the Caucasus, ostensibly for his health but really as an exile. Within four months he regained much of his old power and seemingly healed the breach with Stalin.

But it was only a brief truce. The mills of Stalin kept grinding and did not stop until Trotsky was deprived of every office and honor. When the tenth anniversary of the establishment of the Soviet was celebrated, in November, 1927, and a great parade of the Red Army was held in Moscow, Trotsky, who had organized the army and was once its beloved idol, stood in the street with other spectators, almost unnoticed, and watched it march by.

If the news emanating from Russia in January, 1929, is to be trusted, Trotsky, who had been exiled to Siberia, was, in fact, preparing for a return to power by means of a revolution. On Jan. 23 it was announced that 150 followers of Trotsky had been arrested and after summary trial sent into “rigorous isolation” in a number of prisons as “enemies of the proletarian dictatorship” for plotting a civil war against the State.

In the days succeeding the wholesale arrests, rumors came thick and fast that Trotsky was en route to Turkey, whence he had been banished. Official Moscow kept silent, but on Feb. 1 The New York Times correspondent definitely announced that the decision to send Trotsky out of the country had been taken.

Thus Trotsky, who in 1917 was being hailed as the “Napoleon of the Revolution,” ended, like Robespierre, a victim of the very forces he had done so much to create.

On Feb. 6, 1929, he arrived at Constantinople with his family, and busied himself with writing his memoirs and pamphlets by the hundred. It was during this stay that he wrote his voluminous “History of the Russian Revolution,” a work that bitterly attacked Stalin and sought to prove that there were two great men of New Russia—Lenin and Trotsky.

His daughter, Zinaide Wolkow, committed suicide in a Berlin rooming house in 1933. Trotsky blamed it on Stalin, because the dictator had refused to admit her to citizenship in the Soviet land.

In July, 1933, he arrived at Marseilles and received sanctuary through the French Government. Less than a year later he was expelled because he had “not observed the duties of neutrality.”

Trotsky, accompanied by his family, arrived in Oslo in June, 1935. In August, 1936, after a period of comparative quiet, he was again in the midst of turmoil, emanating from the trial of sixteen Bolsheviks in Moscow, the so-called Zinovieff-Kameneff trial. They were accused of conspiring with Trotsky to assassinate Stalin and other Soviet leaders and restore capitalism in Russia. Tried in absentia, Trotsky was pictured as the villain of the alleged conspiracy.

The verdicts of guilty were founded wholly upon confessions of the accused, which Trotsky denounced as false, characterizing the trial as a frame-up. He demanded an impartial investigation of the charges and threatened to sue a Communist paper in Norway for libel because it repeated these accusations as proven. The Norwegian Government, however, forbade him to bring the suit.

After the trial the Soviet Government demanded Trotsky’s expulsion from Norway, and although Norway declined to accede to the demand, it finally declined to renew his residence permit. Eventually the Mexican Government permitted him to come to Mexico on condition that he would not interfere in Mexican affairs.

He had no sooner taken up residence in a villa outside Mexico City than his peace was again disturbed by another treason trial in Moscow, this time of 17 Bolsheviks accused of counterrevolutionary activities. They, too, confessed, involving Trotsky as their leader.

For weeks he supplied the American and world press with statements and articles refuting the charges, accusing Stalin of trying to liquidate the Communist party and the revolution and establish a Red fascism in Russia.

To the last moment of his life Trotsky remained a stormy petrel, clinging to his extreme Communist ideas, particularly his theory of permanent revolution. Few men have ever provoked such hatred in some and such devotion in others as Trotsky. Whatever history’s verdict upon him may be, it will not fail to record that he helped fill some of its most colorful pages.

BENITO MUSSOLINI

July 29, 1883–April 28, 1945

MILAN—Benito Mussolini came back last night to the city where his fascism was born. He came back on the floor of a closed moving van, his dead body flung on the bodies of his mistress and twelve men shot with him. All were executed yesterday by Italian partisans. The story of his final downfall, his flight, his capture and his execution is not pretty, and its epilogue in the Piazza Loretto here this morning was its ugliest part. It will go down in history as a finish to tyranny as horrible as any ever visited on a tyrant.

As if he were not dead or dishonored enough, at least two young men in the crowd broke through and aimed kicks at his skull. One glanced off. But the other landed full on his right jaw and there was a hideous crunch that wholly disfigured the once-proud face.

Mussolini wore the uniform of a squadrist militiaman. It comprised a gray-brown jacket and gray trousers with red and black stripes down the sides. He wore black boots, badly soiled, and the left one hung half off as if his foot were broken. His small eyes were open and it was perhaps a final irony that this man who had thrust his chin forward for so many official photographs had to have his yellowing face propped up with a rifle butt to turn it into the sun for the only two Allied cameramen on the scene.

—Milton Bracker

Benito Mussolini, founder of Fascism and for more than 20 years the ruler of Italy in all but name, was the first of the modern totalitarian dictators to achieve power, as he was the first of them to lose it.

His career, from its beginnings in obscurity to its end, was unfailingly colorful and dramatic. Never was this more true than in his downfall, which served to provide one of the great turning points of the World War for which he bore such a heavy burden of responsibility.

Although the Fascist regime had been badly shaken by the Axis defeats in North Africa and the loss of the Italian Empire on that continent, it was the invasion of Sicily by the Anglo-American forces under Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower that set in motion the chain of events that culminated in the overthrow of Il Duce.

Mussolini was born on July 29, 1883, in the hamlet of Dovia, Province of Forli. His parents were miserably poor. As a boy he was unruly, turbulent and aggressive. On completing his elementary education he became a teacher, but soon tired of this life. He wandered through Switzerland, Germany, France and Austria, working as a bricklayer, station porter, weaver and butcher’s boy. In the evenings he attended various universities, or studied alone.

Returning to Italy he became prominent as a Socialist agitator in Forli. He founded the newspaper Lotta di Classe—Class Struggle—which became the local Socialist organ.

Mussolini stood trial for his active stand against the Italo-Turkish war, but was acquitted. His oration in his own defense helped win him national recognition as the leader of the left wing of the Socialist party, the place he held when the first World War broke out.

Within a few months he swung violently away from his radical position to one of active championing of Italian entry into the war on the side of the Allies. For this he was denounced as a traitor by his former Socialist comrades, who contended, probably truly, that he had been subsidized by Allied propagandists.

After Italy declared war on May 23, Mussolini, assigned to the Bersaglieri, made an exemplary soldier. He was wounded several times and repeatedly mentioned in dispatches.

After the war Mussolini secretly allied himself with the most reactionary elements. He founded the Fasci di Combattimento in Milan in March, 1919, for the avowed purpose of fighting the widespread unrest. The movement received a great impetus when the Italian Government sent Italian troops to fire upon Gabriel d’Annunzio and his followers in Fiume.

This move sent thousands of volunteers flocking to the standards of Fascismo. When the anarcho-syndicalists, with some help from the Communists, occupied a number of Italian factories, the Fascisti turned on them fiercely and, when the strike collapsed quickly, set up a fanfare about how they had saved Italy from a Red revolution. Actually, some historians believe the alleged strikes were deliberately fomented by a provocateur.

By the autumn of 1922 the Fascist party claimed more than 1,000,000 members. On Oct. 24 of that year, Mussolini issued this ultimatum to the Government:

“Either the government of the country is handed to us peaceably or we shall take it by force, marching on Rome and engaging in a struggle to the death with the politicians now in power.”

Four days later the black-shirted legions began the march on Rome from their headquarters in Milan, discreetly followed by Mussolini in a sleeping car. The Cabinet declared martial law, but King Victor Emmanuel refused to sign the decree. The Cabinet resigned and the King asked Mussolini to form a government.

He first formed a coalition Cabinet, although the Fascists were, of course, dominant. He himself took the posts of Minister of War and Minister of the Interior, and demanded a grant of extraordinary power from the Chamber of Deputies to balance the budget, solve the labor problem and revise Italy’s foreign policy.

Within a month he used these powers to make himself dictator. He began a drastic overhaul of the entire governmental machinery, displacing old government employees by members of his own black-shirted militia. He boasted that he would make Italy powerful, prosperous and efficient and would make the dreams of Mazzini and Garibaldi come true.

He and his unruly young Blackshirts were ruthless in grinding down these opponents, raiding political meetings and newspapers, burning buildings, disciplining obstreperous opponents with beatings and forced doses of castor oil.

Mussolini and his regime met its first great crisis in June, 1924, when Giacomo Matteotti, leader of the Socialist party and the only outstanding politician who continued publicly to defy the dictator within Italy, disappeared. Well-known Fascists were arrested as his kidnappers. When Matteotti’s murdered body was found later in the summer, a world-wide storm of indignation broke.

For a time Mussolini seemed in danger of falling, but he used the crisis ruthlessly as a means of extending his power. He abandoned all pretense of a coalition government and substituted one that was frankly Fascist. Under fascism the Government regimented every aspect of the life of the Italian people and their industry.

Although Mussolini did not regard himself as a “good” Catholic, he made enough concessions to the Roman Catholic Church to keep it friendly toward him.

Mussolini’s foreign policy was ultra-nationalistic and ultra-militaristic. As early as 1923, in the Corfu incident, the Italian fleet had bombarded the Greek island of Corfu in a dispute over the murder of four Italian commissioners. Greece appealed to the League of Nations, but Mussolini refused to recognize the right of the League to interfere.

More than a decade later he again defied the League and risked war with Great Britain when he began the carefully planned conquest of Ethiopia, which shattered the Four-Power Pact of 1933, in which Great Britain, France, Germany and Italy undertook to guarantee the peace of Europe for ten years.

Mussolini took advantage of border clashes between his troops and the Ethiopians as a pretext for the invasion, which began on Oct. 2, 1935. The Ethiopians were overwhelmed.

In May, 1936, the Council of the League of Nations refused Mussolini’s request to drop the sanctions that it had imposed, whereupon the Italian delegation walked out of the Council chamber. Friction continued between the British and Italian Governments, and British fleets were stationed in the Mediterranean. After several weeks’ tension, however, the British withdrew their ships. Later the League of Nations likewise dropped its sanctions.

Hardly had this dispute been settled when the Spanish Civil War broke out. Although Italy joined the other Western European powers in a non-intervention pact, Mussolini at first covertly and later openly sent men, arms and money to aid the rebel forces.

The hatred of Britain that Mussolini felt as the result of the sanctions policy was ameliorated little if at all by the effort at appeasement that followed the advent of Neville Chamberlain to power. This led eventually to the outstanding event of Italian foreign policy under Mussolini—the formation of the celebrated Axis with Germany, at first a secret and then an avowed declaration of solidarity.

The first important fruit of that agreement was the occupation of Austria by German troops in March, 1938. Afterward, Mussolini exchanged telegrams pledging continued friendship with Hitler.

In the succeeding crisis over Czechoslovakia, Mussolini and Hitler were again found side by side. During the days of greatest tension Mussolini called upon France and England to abandon this smaller democracy.

Despite his truculence, Prime Minister Chamberlain of Great Britain turned to Mussolini to use his good offices to keep Hitler from marching into the territory of the Sudeten Germans. Mussolini persuaded Hitler to meet Mr. Chamberlain and Premier Daladier at the Munich conference, at which Czechoslovakia was partitioned.

Soon, Mussolini took a more and more pronounced pro-Nazi attitude. His henchmen set up a cry for Corsica and Tunisia, French possessions with large Italian populations. He introduced a series of anti-Semitic measures and speeded up preparations for the war that seemed inevitable.

When it came, with the German invasion of Poland on Sept. 1, 1939, Mussolini was silent. It was not until Sept. 23 that he declared his intention of maintaining Italy’s neutrality. This position he maintained, although with marked indications of pro-German sympathy, until the German onslaught crushed the French Army. Mussolini took his country into the war on June 10, 1940, two days before the Germans reached Paris. [Prime Minister] Churchill likened his action to that of a jackal.